Brazing and Soldering

BRAZING AND SOLDERING, the process of uniting two metallic surfaces together by means of a fused metallic ma terial joining them (cf. WELDING) ; usually distinguished as hard soldering or soft soldering. In each the melting temperature of the solder is lower than that of the metal or alloy to be united. This is more markedly so in the case of soft solder, which makes a joint without producing discoloration by heat, an important ad vantage in tinware. Hard solder, or brazing spelter, makes more intimate union with the work, hence the result is stronger. But soft solder is quite satisfactory for tinware, lead, plumbing, pew ter, Britannia metal, while brass, copper, iron and steel may be soldered for some purposes, or brazed together when greater strength or resistance to heat becomes essential; aluminium is not so simple to solder as the other materials. There are a great many recipes for the compositions of solders, according to the class of material to be joined, and numerous types of joints. A flux is al ways necessary to ensure chemical cleanliness.

For brazing, heat must be obtained from a clear fire, a blow pipe or blast flame, the grip of red-hot tongs, or by having the spelter molten in a bath. The flux, such as borax, is applied while the joint is hot, and the spelter put on in convenient shape—thin sheet, strip, wire, or small lumps, which melt and run freely be tween the faces. A handy form of brazing medium is sold com bined with the flux, pieces being broken off and used without the need for separate fluxing. If the flow is not certain to spread properly between a joint, notwithstanding a jarring action being given to help matters, it is preferable to sandwich the spelter in, and draw the parts together by means of wire bound round or with the tongs, while clamps are utilized for some articles, such as the thinned ends of band-saws which are held overlapping in exact position during the process. Dipping into a molten bath af fords the best mode of even penetration for some joints, notably those of cycle frames.

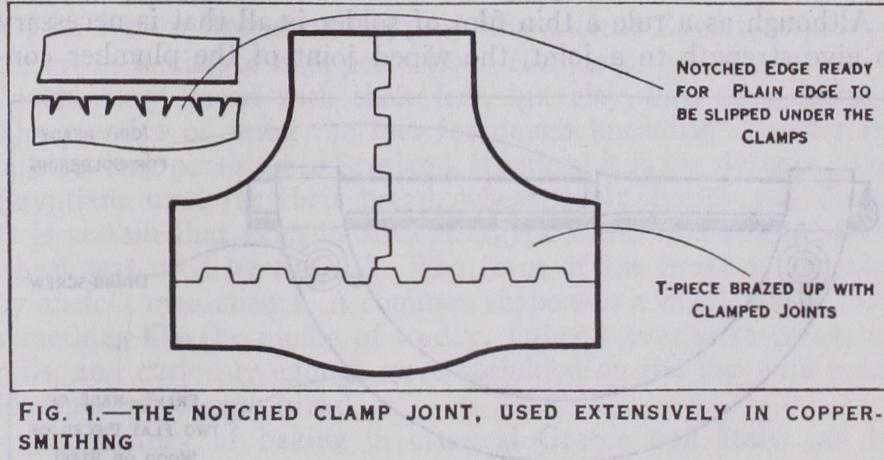

Should parts not fit together rigidly, or extra strength be re quired, additional resistance to bending or twisting stresses can be gained by putting pegs through a joint, inserting liners in tubular joints, or serrating faces so that the spelter runs into the grooves and forms so many keys. Rather thin metal, such as in copper-pipes and fittings made for ships, distilleries, breweries, etc., is brazed up with "clamped" joints for extra security and re sistance to the internal pressure of steam or other fluid. One edge is left plain, the other has notches cut, as evidenced from the detail in fig. 1, and each alternate "clamp" is lifted slightly so as to enable the other plain edge to be slipped in. After hammering or closing the joint neatly, it is jarred to bring about a slight freedom for the spelter to flow into. The employment of a solu tion of borax and water as a flux also ensures perfect preparation of the faces. Joints are also thinned, as well as clamped, in order that the total thickness shall not much exceed that of the sheet, if at all. The other view shows a copper three-way or T-piece brazed up with clamped joints. Annealing has sometimes to be done, of ter brazing, and hammering a joint neatly, to obviate risk of cracking.

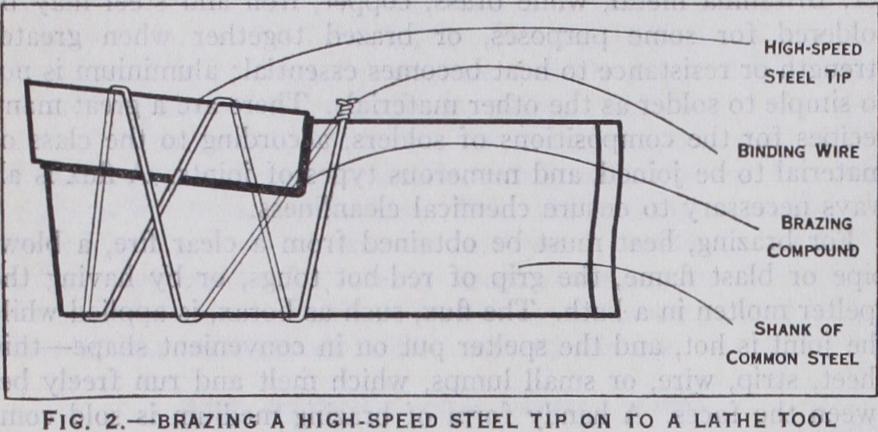

An example of support afforded in a joint appears in fig. 2, in which case a great force tends to tear the parts asunder. This is a tool used in a metal-turning lathe, and made up with a long shank of mild or of low-carbon steel, to which is brazed a tip of the expensive high-speed cutting steel. This rests on a ledge on the shank, and is often additionally locked by fitting it on a vee surface instead of flat, so as to resist side movement. The brazing compound is sandwiched in, the parts bound with brass wire, and heat applied in the fire or gas-blast.

Electric brazing is performed by gripping the parts in the elec trodes of an electric welder type of machine. The spelter and flux are applied, and the current switched on, raising the joint to a sufficient heat for fusion.

The lower temperature that suffices for soft soldering rather simplifies the methods. A copper soldering-bolt may be pressed on the work to cause the solder to run, or drawn along to make it flow from a stick in the required direction. The blowpipe gives a delicate and perfectly controllable flow, and small joints are preferably made with its help. Sweating is a convenient mode of uniting some specimens, heat being applied throughout the area. Pouring from a ladle is done when a considerable quantity of solder must be applied ; this is so in regard to water-pipes hav ing to withstand a good pressure.

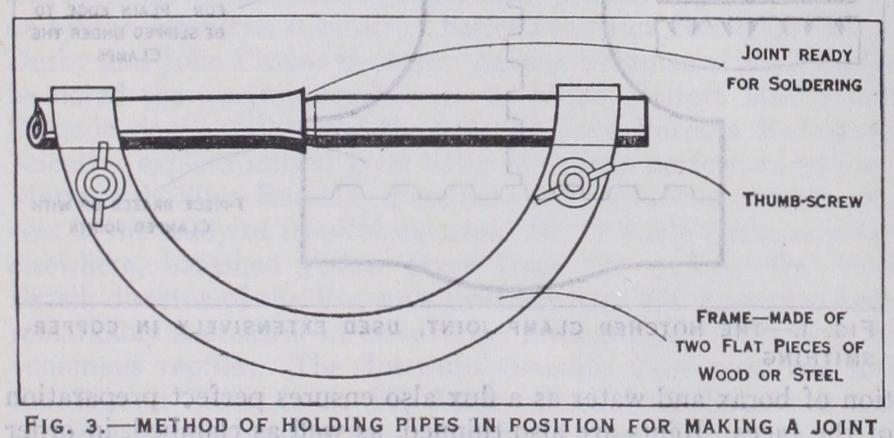

Support has to be given to some objects which do not retain their relationships naturally, including certain frames, and pipes, complicated by overhanging details. CIay, charcoal blocks, or screw clamps variously take care of these subjects; fig. 3 repre sents a divided clamp which locates pipes in their setting for a wiped joint. If faces are not bright, they must be filed, ground, scraped or shaved, or polished with emery-cloth, and a flux is req uisite to clear away oxide. Fluxes include rosin, sal-ammoniac, tallow, chloride of zinc solution (killed spirits), or one of the proprietary pastes sold in tins. "Tinning" is a process required for two reasons: to prepare faces in iron, copper, and brass ready for adhesion of the solder, and to cover the nose of the soldering iron so that oxidation will not occur while it is being used. A flux is applied to the cleaned metal in either instance, and the solder allowed to run thoroughly.

Although as a rule a thin film of solder is all that is necessary to give strength to a joint, the wiped joint of the plumber con stitutes an exception. One end of a pipe is opened out with a conical bobbin driven in, the matching end is coned (fig. 3) and the surfaces shaved clean. Pouring is done from a ladle, using a thick cloth to control the plastic mass and wipe it into a neat shape. Blacklead may be rubbed on surfaces to which solder must not adhere, or a mixture termed "soil" or "smudge." The tinsmith uses soldering machines to hold cans, etc., in cer tain attitudes, while being soldered, while in the large canning factories for fish, fruit, or vegetables automatic machines are in stalled, which pass tins along by conveyors, and the fluxing and soldering are effected with great rapidity. Some will do 40,00o or more cans per ten-hour day, that is 8o,000 ends.

The f ollowlng give a few of the very many solders in use :- Coarse Solder Lead 3 parts, Tin i part Plumber's Solder Lead 2 parts, Tin z part Fine Solder Lead i part, Tin I part Tinman's Solder Lead 2 parts, Tin 3 parts Ditto, fine Lead i part, Tin 2 parts Pewterer's Solder Lead 4 parts, Tin 3 parts Bismuth Solder Lead i part, Tin i part, Bismuth i part Hard Solders Copper 2, Zinc i ; Copper 1, Zinc i ; Copper 3, Zinc I.

For Silver Copper 1, Brass 1, Silver 19 ; Brass i, Silver 2.

For Gold Gold, silver, and copper or brass in varying pro portions according to the carat of the gold to be soldered. (F. H.)