Breitenfeld

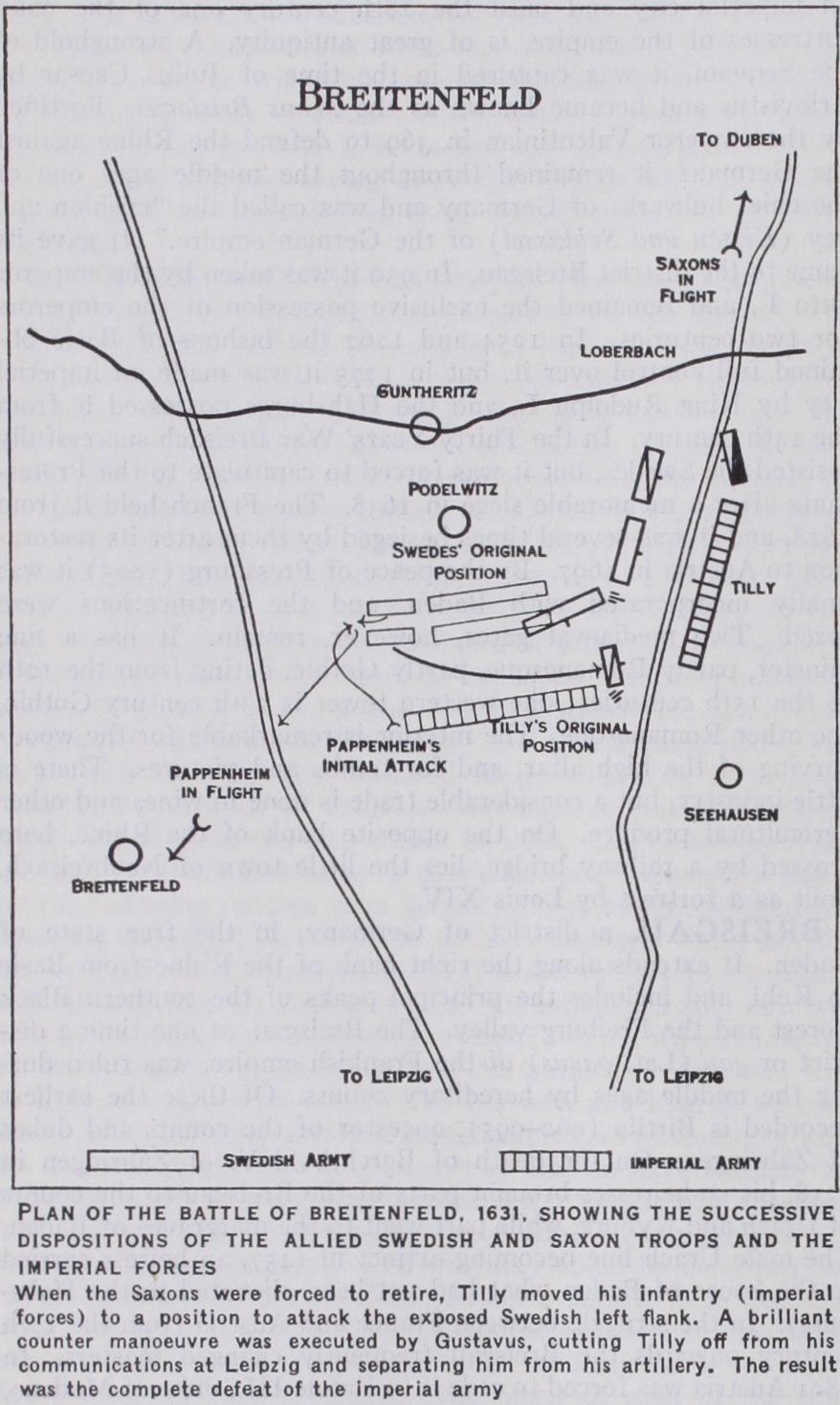

BREITENFELD, a village in Saxony, 52m. N.N.W. of Leip zig, noted in military history. The first battle of Breitenfeld was fought on Sept. 17, 1631, between the allied Swedish and Saxon armies under Gustavus Adolphus and the imperial forces under Count Tilly (see THIRTY YEARS' WAR). The latter's invasion of Saxony had driven the Elector to abandon his long-sustained neutrality, and his urgent appeal for aid had brought Gustavus from the Elbe. On the plain between, but in advance of the villages of Seehausen and Breitenfeld, on the crest of a gentle slope, Tilly drew up his army in order of battle, covering a front of about two and a half miles. Controversy has raged on many of the details, not least Tilly's original dispositions, although it would seem most probable that it was originally formed in two, with a reserve in the rear, rather to the right centre behind the guns and on a slight elevation. When, however, the rout of the Saxons gave him the opportunity to move his infantry to the right to attack the exposed flank of the Swedes, he probably pushed the "battalia" of his second line forward into the inter vals of the first line for the purpose of this oblique move and attack. The infantry formed 13 or 17 solid squares of from 1,500 to 2,000 men apiece. Tilly's cavalry were on the two wings, as was customary, Pappenheim on the left, Furstenburg and Isolani on the right, a total of about 10,00o, making altogether an army of about 35,00o—rather less than the combined forces of the Swedes and Saxons, but, after the early rout of the latter, far superior to the Swedes alone. Only in guns had Tilly a marked inferiority.

Early in the morning of Sept. 17, 1631, the allied armies, in two columns, Swedes on the right and Saxons on the left, crossed the Loberbach, a marshy stream running across their front. The formality of the time is well shown by the failure to fall on Gustavus during this crossing. Only Pappenheim with some 2,000 cavalry went forward to hinder the advance, but the Scots of the vanguard, supported by dragoons, drove him back. Gustavus formed his army in two lines and a reserve. On his left was drawn up the Saxon army. By noon the armies were in position and the battle opened with an artillery duel, in which Torstensson's guns fired three shots to the imperialists' one. This continued for over two hours, when the fiery Pappenheim, without awaiting orders, moved his cavalry to the left to outflank the Swedish right, and then swinging round struck at the Swedish flank. The manoeu vring power and flexible formation of the Swedes enabled Gus tavus to wheel up his second line cavalry at right angles to the first and so form a defensive flank, which, strengthened by mus keteers, proved a rampart on which Pappenheim's cuirassiers broke themselves to pieces.

After seven vain assaults the imperial cavalry fell back dis couraged, and, followed up sharply by the Swedes, were driven in flight from the field. Meanwhile critical events had been taking place on the other wing. The imperial cavalry, under Fiirsten burg, had fallen on the Saxons, and in a short half hour almost the whole army, infantry and cavalry alike, were in disorderly flight—thus laying bare the flank of the Swedes.

Inspired by the rout of the Saxons, Tilly now ordered his centre to move to the right and follow in the wake of Fiirstenburg, and by an oblique march brought his heavy infantry "battles" into line on the flank of the Swedes. It was a manoeuvre in which we can perhaps find the germ of Frederick the Great's famous "oblique order" of attack. But he was meeting an alert, not a supine enemy, and one, moreover, whose flexible forma tions enabled him to manoeuvre more quickly than Tilly's un wieldy squares. Horn, commanding the Swedish cavalry on this wing, swung back his first line and wheeled up his second to oppose a new front to this attack in flank, while Gustavus hurried infantry from his second line to reinforce him and prolong the line. With the issue still uncertain, there came a decisive stroke; with his right wing now secure, since Pappenheim's flight, Gus tavus himself, taking a large part of his right wing cavalry, swept round and over Tilly's original position, where his guns remained, cutting him off from Leipzig. The captured guns were turned to enfilade Tilly's new left flank, while Torstensson with the Swedish artillery pounded his front, and Gustavus made a general wheel with his centre and right to attack the imperial left. Assailed in front and partly in flank, with their close-packed ranks torn by a double weight of artillery fire, the rigid and immobile impe rial squares could but offer a hopeless resistance. The end was inevitable, and though their stand was magnificent, nightfall saw the scattered remnants in headlong flight. The long invincible imperial army, under whose iron heel all Germany had lain prone in ruin or terror, was not merely defeated but destroyed for all practical purposes of resistance. Apart from an actual loss of about 12,000, the fugitives were so dispersed that Tilly on his retreat could rally but 600 and Pappenheim only another 1,400.

The victory struck terror into the hearts of the empire—Vienna was said to be "dumb with fright," Bohemian forests were laid low to block the road, the walls of cities hundreds of miles from the battlefield were kept manned. For the moment the emperor could raise no effective forces to oppose Gustavus's advance. At a council of war the Elector of Saxony and Count Horn, besides many other officers, advocated an immediate advance on the imperial capital. More notable still, Oxenstierna the prudent, though not present at Breitenfeld, was strongly in favour of this plan. But Gustavus decided otherwise—to move into south-west Germany, giving as his reasons that he did not wish to lose sight of Tilly, and that he wished to make use of the resources of the Catholic dioceses there for the maintenance of his army, so allowing the Protestants of North Germany a chance to recu perate.

Whether his decision was guided by the highest wisdom is a moot point. Those who support it point to the value of con solidating his position, of rallying new friends to his standard, and simultaneously gaining a grip on the territories of the Catholic League—thus he could organize a fresh centre of Protestant power before attempting greater schemes. On the other hand, we need to remember that this move on the Rhine earned him the distrust of France, his ally, and that never again did the imperial power appear so shaken, or its seat so defenceless, as on the morrow of Breitenfeld.

The village of Breitenfeld also gives its name to another great battle in the Thirty Years' War (Nov. 2, 1642), in which the Swedes under Torstensson defeated the imperialists under the archduke Leopold and Prince Piccolomini, who were seeking to relieve Leipzig. The Swedish cavalry delivered the decisive stroke of the day on this occasion also. (B. H. L.H.) BREITNER, GEORGE HENDRIK Dutch painter, was born Sept. 12 1857, at Rotterdam. He began to study painting at The Hague, and was a pupil of William Maris. His early work showed the influence of Rochussen, who was the first to discover Breitner's great talent. In later years he was strongly influenced by Jacob Maris's colouring, but afterwards became an independent impressionist. The subjects of his pictures were chosen from old parts of Amsterdam, from popular life in the town or from the vigorous movements of manoeuvring cavalry and artillery. He died at Amsterdam June 5 1923.