Bricklaying

BRICKLAYING Certain essentials in building good brickwork are :—Accuracy in working to ensure a perfectly horizontal bed and that walls are vertical, or, if the outer face is battered (sloped), that the angle of the batter is maintained. A bricklayer usually first builds up the quoins (angles of building) six or eight courses high, and hav ing got these absolutely true he proceeds to lay courses the whole length of wall between. For the quoins he uses his square, spirit level and plumb to ensure accuracy and then stretches a line the exact height of the next course he has to lay for the whole distance between the quoins. Bricks are laid with the frog (the hollow on one side of the brick) uppermost. It is essential that all joints should be filled with mortar ("well flush up the cross joints"), otherwise the work will be weak. This is so obvious as to appear unnecessary to mention, but bricklayers habitually neglect to flush up and that this must be done has to be impressed frequently upon the foreman. In dry weather bricks must be wetted. Men will not dip them into a bucket of water as they lay the bricks because this makes their hands sore. It is usual, therefore, to pour water over bricks before they are laid or to do so on each course, as laid. Neither method is entirely satisfactory but either is better than perfectly dry bricks, which absorb the moisture from the mortar before it has set, so that it never really unites with them. In wet weather bricks should be protected from excessive rainfall or this will protract the setting of mortar and work will not be ready for succeeding courses when it should be. Brickwork must not be carried up too quickly lest the work should settle and so be out of plumb, for this reason it is usual only to carry up work three or four feet at a time, and to do so evenly all round the building.

Mortar.

Good brickwork implies good mortar, whether of lime or cement. If the sand used is not clean and sharp, or if it is earthy the mortar will not be strong. Lime mortar should be used within ten days of mixing ; cement mortar should be mixed in small quantities and used within half an hour. (See MORTAR.) The effect of frost upon mortar that has not had time to set hard is to destroy its properties. The exact degree of cold at which bricklaying should be stopped depends upon several factors, but the addition of a proportion of unslaked lime (the amount of which will vary with the degrees of frost registered) will enable work to be continued for some time. Green brickwork may be protected; but the perfunctory protection afforded by laying empty cement bags or a tarpaulin over newly built work is neg ligible.

Bonding.

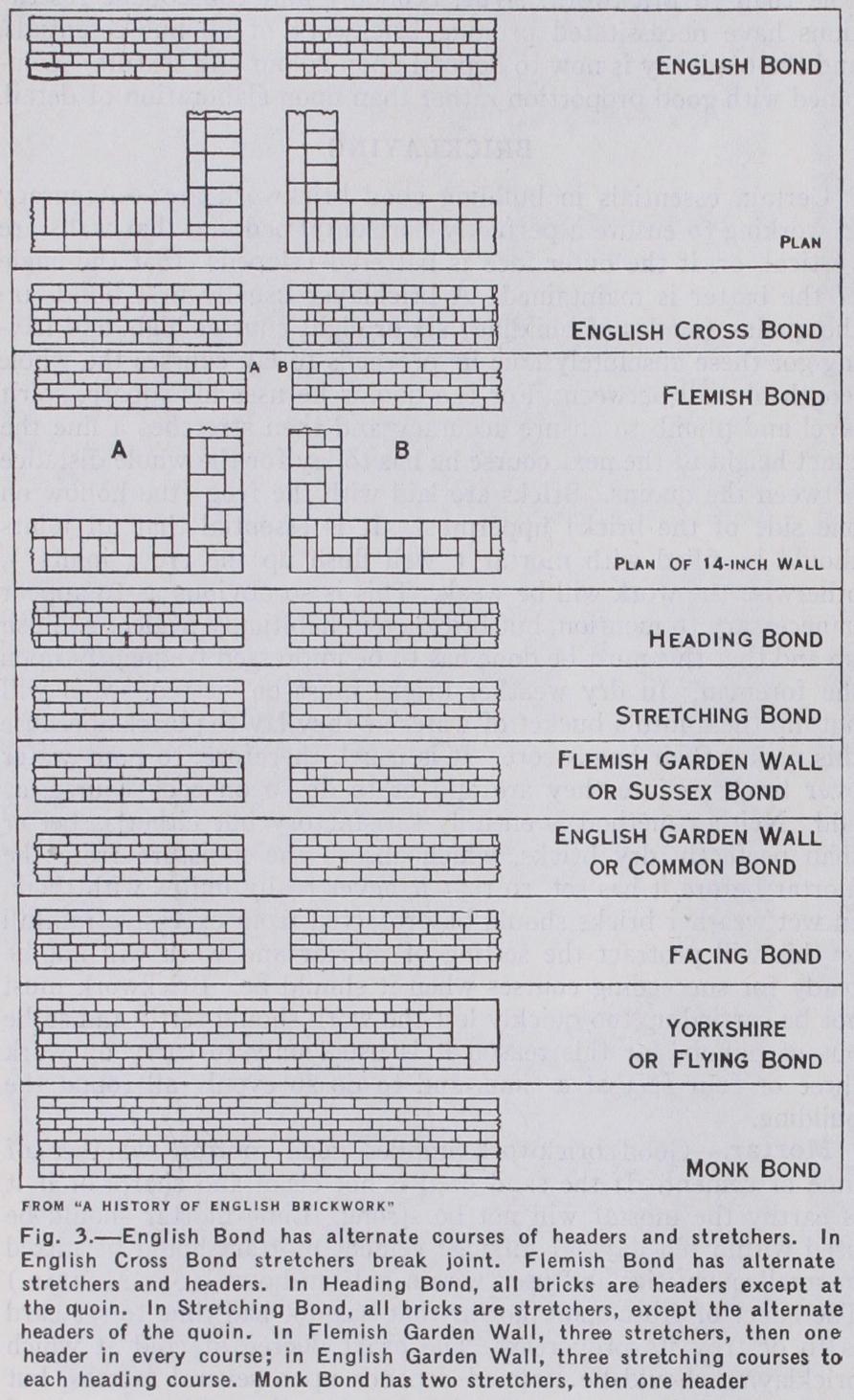

Bonds are the arrangements of bricks by which each brick overlaps another by a quarter of its length or 2+ inches. Bonds are recognised by the arrangements they present on the faces of walls and frequently the substitution of one bond for another may enhance the appearance of brickwork without im pairing its strength; although the primary object of bonding is to secure the greatest possible strength to the structure. Only four bonds are commonly found in England. They are English, Flemish, Stretching and Flemish Garden Wall bonds. The first three are used for buildings, the last one for single brick (gin.) walls where both sides of the wall are seen. There is no reason, save lack of enterprise, why other bonds should not be employed. In fig. 3 bonds are illustrated, the arrangement on face and return walls being shown in each, together with a short definition to assist in distinguishing one from another. English bond, which consists of alternate courses of headers and stretchers, is regarded as the strongest of all. English Cross bond and Dutch bond are merely variations of it : used for an unbroken wall surface, they produce a multitude of little crosses, which form a pleasant variation but too much of which is distressing to the eye. Flemish bond con sists of alternate headers and stretchers in the same course, and is inferior in every respect to English bond, though preferred by those who strive after "neatness." It was introduced into this country about 163o; not by William III., as often stated, though by the end of the 17th century it had almost entirely supplanted English bond. Heading bond is obviously weak and is only used where strength is not required and for curved walls. Stretching and Facing bonds are used for walls of only half brick (41in.) thickness. Both are ugly and it is surprising they should be tolerated.

Flemish Garden Wall or Sussex bond consists of three stretchers to one header, repeated in the same course and, as stated above, is used for gin. walls. The reason is that, owing to the unequal shrinkage of bricks in burning, lengths may vary as much as tin. and some headers in single brick walls built in English or Flemish bonds would project beyond others, producing an un equal and lumpy surface. By using Garden Wall bond fewer headers are needed, and these are picked out to one length before building is begun. English Garden Wall bond consists of three courses of stretchers to each course of headers. In the North of England five courses of stretchers go to one course of headers and this is also the practice in the United States, where this bond is called common bond. Like Flemish Garden Wall bond, bricks of even length are picked out for the header courses before the work begins. Either of these Garden Wall bonds may be used instead of Stretching or Facing bonds for half-brick walls (e.g., the out side skin of a cavity wall). The additional cost, if any, is trifling, for the headers will be half bricks (snap headers) in such walls and there are always some broken bricks which can be used up. The improved appearance by comparison with Stretching Bond is remarkable.

Yorkshire or Flying Bond has no practical value. It was in vogue at a time before bonding was thoroughly understood in England. Monk Bond consists of two stretchers and then a header throughout in the same course. It is the bond used for centuries in Northern Germany and Scandinavia. Over a large wall surface it produces a series of chevrons five courses high—a pleasing variation which is not worrying to the eye. By modifying it, and using headers with burnt ends (grey ends), vertical bonds may be produced, but these will be referred to later.

Types of Brickwork.

English brickwork may be divided into three distinct types:— I. The Tudor, Plate II., fig. 7, in which the bricks are rough in form, are twisted, are irregular in outline and are built with joints from to fin. thick. These bricks vary much in colouring and include plum reds, yellow reds, browns and bluish greys. Few modern attempts to produce Tudor brickwork include all these characteristics, yet no brickwork is so generally admired as the old. 2. The i8th century brickwork, Plate II., fig. 5, a type which actually came into fashion in the latter part of the i 7th century. The bricks are regular in size and form, with sharp arrises (edges) ; they are built with joints never exceeding fin. (often only +in.) thick, and the bond is usually Flemish. Bricks vary with the clays of the locality in which they are made, from deep red to the yellow and grey stocks so largely found in London. 3. Gauged brickwork, Plate II., fig. 1. Sometimes whole fronts are built in this manner, but usually piers, panels and dressings. The bricks are rubbed exactly to one size and perfectly smooth on face, with sharp arrises, and they are built with very thin joints ( or in.) with lime-putty for mortar. If judiciously employed such brickwork has very high value. Its application may be seen in the portion of a pilaster in Plate II., fig. 5. The earliest gauged work (gauged-measured) in England is about 1630. Plate II., fig. 1, of a window and pilasters at Kew Palace, is dated 1631. The work is gauged but not with that fine accuracy shown in the capital and wall behind in Plate II., fig. 6, which is from an example which represents the highest attainment yet achieved in this kind of brickwork.Joints and Pointing.—Stronger and better work is obtained by leaving a rough flush joint or by striking a joint with the trowel at the time when bricks are laid than by raking out joints fin. and pointing afterwards ; though the latter course ensures a more regular and even appearance. For the Tudor type of brick work, Plate II., fig. 7, the mortar of joints should be left full and squeezed out by pressure when laying the bricks. The superfluous mortar will fall off itself under influence of the weather, leaving a natural surface. If there is any cement in the mortar, or if for any reason a more formal joint is required, the weather struck joint is best. This is a method which makes the bricks of the upper course throw a slight shadow and water does not lodge on the lower course as when struck the wrong way. Also, when wrongly struck, water penetrates above the joint which frost disintegrates. Old brickwork may have to be re-pointed. When this is necessary, the joints should be raked out much deeper than fin., which is usual, i yin. is not too much. Objection is sometimes taken to the struck joint for repointing i8th cen tury type of brickwork, where the edges of bricks are worn and broken and where it is desired the wall face should present a neat and formal appearance. In such circumstances tuck pointing is employed, for which the raked-out joints are pointed flush with the wall face in cement or lime mortar and the whole coloured evenly with copperas and coloured pigment, or the whole wall is rubbed over with a piece of soft brick to the colour required. White lime putty or black stopping is then applied to a fine joint which has been raked out in the new mortar and by means of a straight edge and jointer and trimming with a frenchman (a table knife with the point turned up at right angles) a white joint -lin. wide and projecting 'iin. is formed. Recessed, keyed, bastard tuck, and other joints are seldom used now and are not to be recommended.

Hollow Walls.—Fig. 4 shows a section of a small country house built with hollow external walls, instead of a solid wall. Two 4-lin. walls are built 2-lin. apart and are tied together with wrought iron metal ties. The effect is that only the outer wall is exposed to wet, the air in the cavity acts as a non-conductor and consequently the inner wall is warm and dry. Various forms of iron ties are made and some architects prefer glazed brick ties, but the iron ties are most used. At least two are built into every super yard and one to every I2in. height at openings. The section shows the usual practice of brick construction. On the concrete foundation are the stepped footings of brick. Under the floor is a layer of concrete, on which are the sleeper walls, consisting, in this case, of two courses of brick 41in. wide, between which the damp-proof course of the inner wall is continued across to the wall on the other side of the house. On these sleeper walls the floor joints rest. Moisture pass ing through the outer wall falls to the bottom of the cavity and is prevented soaking inwards or up wards by the damp-proof course. Openings at the sides of win dows are sealed with pieces of slate in cement. Over the win dows sheet lead is built into a joint of the outer wall and carried upwards across the cavity into a joint one course higher up in the inner wall. This prevents mois ture from the wet brickwork soaking down through the wood work of the windows. The cavity is ventilated by air inlets passing through the outer wall. It is important that no fragments of mortar should be left which would bridge the cavity, for they would conduct moisture to the inner wall. Such lin. hollow walls are more stable than 9in. solid walls because they have a broader base but would not be permitted in London as substitute for the latter, so that there a 41in. outer and a gin. inner wall would be required. Hollow walls effect economy in expensive facing bricks, as common bricks can be used for the inner wall and only half the number may therefore be required for the half brick outer wall.

Arches.—Any arches that are built in stone may be carried out in brick (see ARCH), but the forms most used are segmental, semi-circular and straight. The segmental and many semi-cir cular arches are built of ordinary bricks (not voussoirs), the dif ference between the curves of extrados and intrados being taken up in the joints, which are wedge-shaped. Other semi-circular arches are carefully gauged. Straight arches (which must be built of gauged voussoirs) used over window and door openings are better built with a slight rise. Even a lin. rise in a aft. open ing avoids the appearance of a sagging lintel, which is not only unpleasing but may cause fracture of the arch in course of time should the mortar have slightly deteriorated. Even a slight rise increases the strength.

Corbelling and Chimney Caps.—The projection of brick corbelling is limited by (i.) the thickness of the wall—but equal corbels on each side of a wall will balance each other—and by (ii.) the tailing-in (the securing of the wall end of a brick). For exces sive projection, as for brick cornices, extra long bricks may be specially made, but skilful men work wonders with bricks of ordinary dimensions, as in the cornices above and below the window in Plate II., fig. I.

A common form of corbelling is in construction of chimney caps, of which an infinite number of well designed old examples exists. With thin bricks and a large shaft, projections may be as much as or more than 6-in. each course. If the shaft is slight or if the bricks are thick, fin. projection may be too great. The old builders seem to have worked less by rules than by trial and experience, and until a cap has been proved satisfactory on a shaft of certain proportions it is wise to proceed in the same way and see at least half a cap built up as a trial. The profiles given in fig. I are all of old caps. Plate II., fig. 2, shows a 16th century chimney having detached, octagonal shafts.

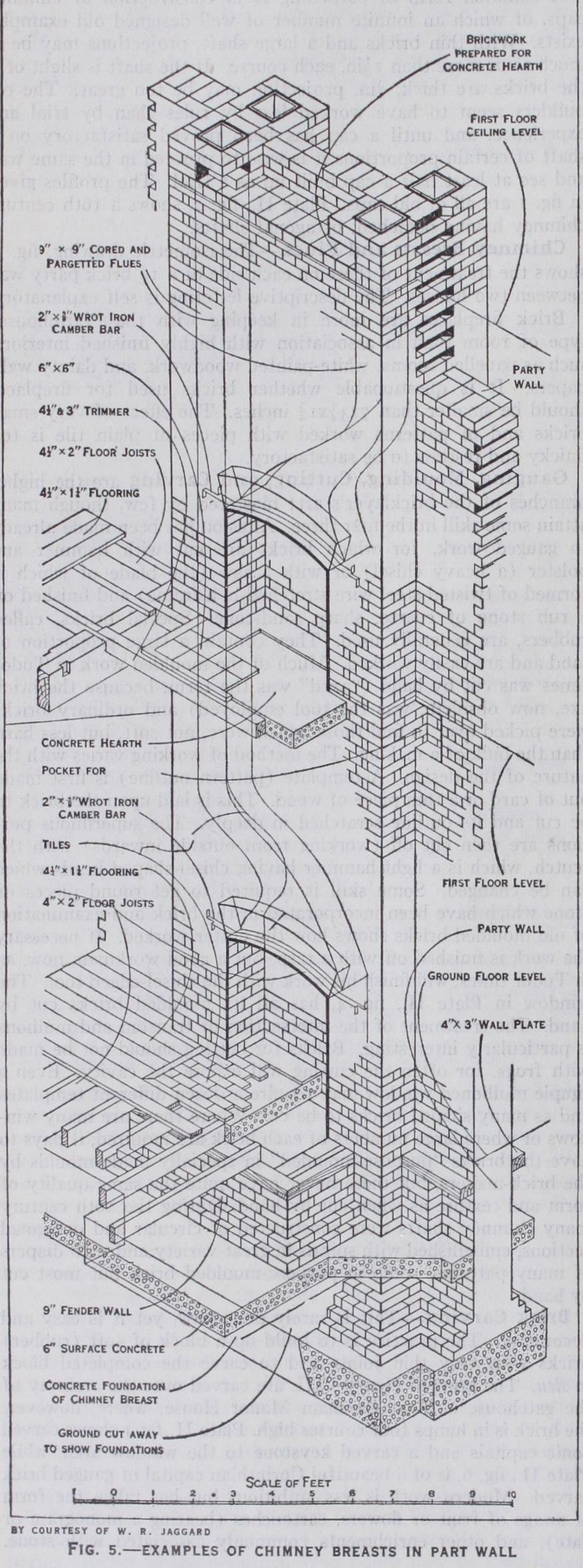

Chimney Breasts and Flues.—The isometric drawing, fig. 5, shows the treatment of these on each side of a I z brick party wall between two houses. The descriptive lettering is self explanatory.

Brick fireplaces are more in keeping with the "farmhouse" type of room than in association with highly finished interiors, such as panelled rooms, white-painted woodwork, and dainty wall papers. It is questionable whether bricks used for fireplaces should be smaller than 7x3 axIf inches. The effect of very small bricks and of patterns worked with pieces of plain tile is too finicky and restless to be satisfactory.

Gauging, Moulding, Cutting, and Carving are the higher branches of the bricklayer's art; mastered by few, though many attain some skill in the first three. Allusion has been made already to gauged work, for which bricks are cut with hammer and bolster (a heavy chisel) or with a saw (the blade of which is formed of twisted steel wire stretched in a frame) and finished on a rub stone of coarse, sharp sandstone. Special bricks, called rubbers, are generally used. They contain a large proportion of sand and are easily worked. Much of the moulded work in Tudor times was cut by hand ("axed" was the term, because the brick axe, now obsolete, was the tool employed) and ordinary bricks were picked over to find those which were, not soft, but less hard than the bulk of a making. The method of working varies with the nature of the design. A template (pattern outline) is first made out of card or a thin piece of wood. This is laid upon the brick to be cut and its outline scratched in deeply. The superfluous por tions are then cut off (working from outside inwards) with the scutch, which is a light hammer having chisel-shaped heads which can be changed. Some skill is required to get round pieces of stone which have been incorporated in the brick and examination of old moulded bricks shows how the cutter worked. If necessary the work is finished off with a rasp, but a good workman, now, as in Tudor times, will finish his work with the chisel-edged tool. The window in Plate II., fig. 4, has all its moulded bricks cut by hand. The treatment of the intersection of transom and mullions is particularly interesting. Bricks for cutting should not be made with frogs, for of ten the cutting will expose the cavity. Even a simple mullioned window may require a dozen different templates and as many shaped bricks to be cut. Where there are many win dows or where large numbers of each brick are required, it pays to have the bricks "purpose-moulded" in specially made moulds by the brick-makers, but these never have quite the same quality of form and texture as when cut by hand. During the 16th century many chimney shafts were constructed of circular and octagonal sections, embellished with spirals in great variety and with diapers of many patterns, some in purpose-moulded brick but most cut by hand.

Brick Carving.—This is rarely done now, yet it is easy and decorative. The practice is to build up a block of soft (rubber) bricks with very thin joints and to carve the completed block in situ. The arms of Henry VIII. are carved over the archway of the gatehouse at East Barsham Manor House, where, however, the brick is in lumps four courses high. Plate II., fig. I shows carved Ionic capitals and a carved keystone to the window arch, while Plate II., fig. 6, is of a beautiful Corinthian capital of gauged brick carved. Modern work is less ambitious but has taken the form of swags of fruit or flowers, cartouches (bearing a monogram or date), and other enrichments commonly associated with stone.

Tools for carving in brick are simple, consisting of a chisel, a bent screw, and a piece of wire gauze to put over the thumb, with which to rub away the soft brick.

Diapers and

Patterns.—These were favourite devices of French builders of the 15th century, the patterns in various coloured bricks being derived from the mediaeval Italian work and their influence is seen in contemporary buildings in England, though not equally varied. Fig. 2 shows some French examples. There was a revival of this use of dark headers in 18th century brick buildings in England, usually by picking out the headers which had grey ends and building these so as to produce hori zontal or vertical bands. Also by building all headers in Flem ish bond, an evenly chequered wall surface was produced. Such restricted methods were often pleasing and more satisfactory than the florid 15th and 16th century treatment. The secret of good results in the use of grey headers is to pick out and use only the soft greys, not the very dark ones. The effect of the latter may be seen in the school buildings at Rugby, which no one would wish to imitate. Strap-work as shown in the panel Plate II., fig. 3, is another excellent form of pattern making.The nature of bricklayer's work varies from the roughest wall ing to that requiring great care, but in estimating for any work it has always been necessary to compute what a man should produce. The compilers of old price books based their figures on what a man would average on ordinary house building, taking one kind of work with another but excluding special works such as gauged work, tuck pointing and fancy work. Men were expected to erect their own scaffolding in the time reckoned, and the working day was ten hours.

In 1667,

I,000 bricks daily for one bricklayer and his labourer. In 1703, I,000 do. do. do. 1,200/1,500 by exceptional men.'734 as in 1703.

1,000 bricks daily for one bricklayer and his labourer. 1,500 if all work was common, rough walling.

1835, 1,000 bricks daily for one bricklayer and his labourer. The modern equivalent, for an eight-hour working day, should be Boo bricks daily.

As many as 809 bricks were laid by one man in an hour at Treeton, York, in 1924, and at Rotherham, in April 1927, William Milnes, a foreman bricklayer, laid 1,121 bricks in one hour--a record not likely to be broken. The work was of the rough kind, which writers quoted above reckoned should be done at the rate of 1,50o daily. Such concentrated effort, assisted by materials being placed by a staff of labourers, bears little relation to daily work but does suggest that, given bricklayers having the will to do more, much might be done to assist output by arranging work and materials conveniently. Detail photographs of the actual operations show the work to have been done from scaffolding and to have been sound and good, as indeed competent eye-witnesses certified it to be; 700 bricks daily is the usual output in the district.

BIBLIOGRAPHY.--W. R. Jaggard and F. E. Drury, ARCHITECTURAL Bibliography.--W. R. Jaggard and F. E. Drury, ARCHITECTURAL BUILDING CONSTRUCTION (1922) ; C. F. Mitchell and others, Building Construction (1927) ; N. Lloyd, A History of English Brickwork (1925), although a complete record of brickwork to the end of the Georgian period, it is so fully illustrated as to be comprehensible by any layman; M. B. Smith, Italian Brickwork (5929) ; B. Langley, The London Prices of Bricklayers' Materials and Works (1749), full of information about methods still practised. (N. L.)