Bridges

BRIDGES. The function of bridges may be described as the starting of a stream of human traffic hitherto impossible; the sur mounting of a barrier, the linking up of two worlds divided by a gulf. One such barrier, the great River Severn, has decided more than once the fate of England. Thus when Margaret of Anjou had crossed to England, just as Edward was disbanding the last of his infantry after Barnet, she attempted to reach Bath, with Edward pounding on out of Cirencester. From then until the battle of Tewkesbury her movements were those of a person who is being chased in the direction of a wall in which there is a gate she cannot find. And eluding, feigning, doubling back, she was brought to a standstill at last and crushed against the barrier she had so desperately striven to cross and could not. In the early hours of May 1, the king, having heard news of her west ward march, "toke advise of his counsell of that he had to doe for the stopynge of theyr wayes, at two passagys afore namyd, by Glocestar, or els by Tewkesberye." It was not only that her men were completely exhausted after their march ; not only that the king was only half-a-dozen miles behind her, "evar redy, in good array and ordinaunce" ; but at Tewkeshury the river became two rivers, and having failed to cross thus far, how could she hope to do so thereaf ter? With the Severn on its right, and the Avon on its left, her army could only stand still and await the death-blow.

Another drama of the same kind, and even more striking though it ended not in massacre but in withdrawal by sea, was set on the banks of the Chickahominy in Virginia during the American Civil War. After long delays General McClellan had succeeded in carrying his plan for an attack on Richmond. When at last his army had been transported to the peninsula it took two more months before they reached the Chickahominy. During that time the rebels had gathered thousands of recruits and an army of slaves was at work on entrenchments. Already the attack was weeks overdue ; every moment wasted increased the exhaustion of the Northern troops and added to the enemy's strength. But for the Chickahominy, Richmond might still have been taken and the subsequent history of the Civil War might have been shorter and very different. Instead, the army, during another disastrous month, lay astride the river, unable finally to cross to this side or that, its ranks daily thinned by malaria and by the unaccustomed heat. If the whole of the men were brought across to the south bank the line of communication with Washington would be imperilled and the stores laid down further north almost certainly destroyed. Yet the army was too small to march on Richmond and leave a guard behind, while to have remained on the north bank would have been at once to acknowledge failure and defeat. Caught in the toils of the Chickahominy it could neither advance nor retreat, and all the while the men knew that nothing could be more perilous than the immobility into which they were forced by their enemy, the unbridged river. The lines extended 20 miles on either side ; and it is true that six or seven dilapidated bridges united them. But six or seven were not enough, and though other bridges were begun in the few places where a crossing seemed approach able, McClellan's troops could never build so many that their movements would become rapid and secure. And so they were held until their danger became too great and began to close round them on every side, so that they had to fight their way out of the trap into which they had so innocently wandered.

The frustration of Margaret's plans was due in part to the immediate action taken by the king, who turned the Severn into his most powerful weapon against her ; the Chickahominy did its work unaided, which may explain how the escape of the imprisoned armies was made possible. When man and nature work in alliance the result is usually more certain. The entrapping of Simon de Montfort at Evesham could only have been contrived by a man completely familiar with the River Avon and its bridges and determined to use both the one and the other to their utmost capacity. With half his army Prince Edward came rushing back from the disabling of young Simon at Kenilworth while the other half marched from Worcester in time to meet him at Evesham; and in order to make sure against Simon's escape, each half divided again at carefully arranged points and united, the one at the next bridge upstream (a couple of miles away) and the other at Eve sham itself, the duke of Gloucester's division rejoining the northern forces by crossing Evesham bridge from the south. In this skilfully planned manoeuvre the Avon crossings were played against Simon as a hand at cards is played, one crossing after another being used and guarded like the opening and shutting of so many doors, and thus made to contribute to the cumulative result that meant a sudden and decisive victory.

Old Bridge Construction.

The history of all old bridges which have survived complete is one of almost continuous repairs, and the written records that remain tell us of the unceasing labours of those who raised funds for their maintenance. Without such vigilant care no masonry bridge, no matter how well built, was likely to last much over a century. Storm and flood, sun and frost, combining with the vibration of traffic, found a weak point somewhere, and, unless the damage was repaired at once, it spread with startling rapidity. True, in the middle ages, when the founda tions of a stable civil government were only gradually being laid, builders made every effort to lessen the need for future repairs by designing their bridges so that an injury would not spread quite so quickly. The piers were so heavily constructed that every arch rested in what was virtually an isolated compartment. But this device brought other dangers and drawbacks, to which some reference must presently be made.The pounding of horses' hoofs above and of angry waters below were enemies above all to be dreaded. It is easy, when we consider these, to understand why the most perfectly pre served and hence the most celebrated of all Roman bridges in Europe should be not bridges properly speaking, but the aqueducts that carried their water supply across a valley. Many of the so called Roman bridges in all parts of Europe are not Roman bridges at all. Of the four in Rome itself, not one contains any masonry that can with confidence be dated earlier than the beginning of the i 5th century. A ruin such as the beautiful single arch over the Tiber at Narni, 5o m. from Rome, is much more likely to contain original stones.

English Bridges.

English bridges have hardly received their proper regard, for the achievement they embody with such modesty is the result not of a single great effort but of centuries of unremitting labour ; great though the effort of building a bridge may have been, it is as nothing beside the efforts required to main tain it. Towards the end of the 14th century, London bridge had attached to it a permanent building staff of a dozen carpenters and masons. Doubtless a great many more were recruited in special emergencies. The financial provisions which enabled these men to be kept at work have made the Bridge House estates committee (the survival of a governing committee set up at the end of Eliza beth's reign) one of the wealthiest bodies of its kind in Europe. The first regular source of revenue enjoyed by London bridge were the rents of the houses and shops on the bridge, which in the r4th century amounted to .116o per annum and in the i 8th century to five times as much. But tolls were already being levied on pas sengers, and landed property bequeathed to Bridge House was bringing in considerable sums; a lucky circumstance when we re member that in the last few decades of its long life the annual maintenance bill for Old London bridge was four thousand pounds. Other and smaller bridges did not present the same problem, but few of them were fortunate enough to be placed in the care of permanent officials at such an early date. Where no warden was appointed the responsibility had to be fixed somewhere by law, and mediaeval records are full of inquisitions and disputes on this point. The case of the Long bridge at Shoreham is typical. The bridge being in a state of dangerous decay, the tenant of the ad jacent land (which belonged to the archbishop of Canterbury) was adjudged responsible, and the bailiffs sold his goods and chattels that the neglect might be made good. Most bridges, how ever, were the subject of some kind of contract with Church or Government which made such hardships less likely to befall a local citizen. The corporation of Berwick, for example, received f 1 oo per annum from the Crown for the maintenance of Berwick bridge, which still survives. No single entry in the Scotch Ex chequer Rolls occurs more often than the words Ad Sustent. (Ad Sustentacionem), under the name of a bridge. Since then, the age of modern local government has of course transferred all responsi bility to local authorities.

Gateway Bridges.

Most bridges before the 18th century were furnished with a gateway which was built either on one of the piers of the bridge or at one of the approaches. These gateways had a fiscal as well as a military use, and were often flanked by a toll-house. Only one example remains in the United Kingdom to-day, that which sits astride the Monnow bridge at Monmouth. Our coaching forefathers found them a serious obstruction and it is surprising to find even this one left. The toll-house on St. Ives bridge in Huntingdonshire no doubt had a gate in its day, but it does not stand beside it now.

Age of Bridges.

So close is the connection between the gen eral development of civilization and the development of its bridges that we can best tell the age of a bridge by measuring its girth of masonry. Sometimes, but not often, a bridge or part of a bridge has a date carved on it ; more frequently there is some written record of building or repair work. Yet even where such records exist it is often impossible to say whether the date they give is that at which the foundations were put down and the arches first built. The gradual widening of the average span, and the gradual_ narrowing of the average pier, give us surer evidence of date. In the British Isles, as Harry Inglis has pointed out, the arches start from the neighbourhood of 25 ft., the average span of those of Old London bridge, about the year 1200, to reach a maximum of 75 ft. about the middle of the 18th century, when modern engineering had its birth, and ,since then the increase has progressed in width with startling rapidity. The obstacle that the bridge presents to the water's flow continually grows smaller, until the suspension bridge leaves next to nothing standing in its way.

The Nodal Bridge.

Among the various parts played by a bridge in human history there is one which is greater than any, and which strangely enough requires that traffic on the river should be considerably impeded. This is the part of what has been described as a nodal bridge. A nodal bridge is one which stands at the point where a busy water-way is crossed by a busy land-way in such a manner that the two streams of traffic are mixed together. Most of the great commercial centres of the world owe their ex pansion, if not their origin, to such a nodal bridge. It is safe to say that had there been no suitable site for a mediaeval bridge any where between Wapping and Charing Cross, London as we know it to-day would never have existed. Moreover, if by some impos sible anachronism Old London bridge had been suspended from a couple of piers as are several of the new bridges above West minster, or if it had opened itself to waterborne traffic with as much ease as the bascules of Tower bridge, the Port of London would never have attained its present rank among the harbours of the world. It was necessary that ships should come in on the rising tide and be arrested by a bridge whose piers were so wide that they dammed up the Thames like a millrace. And it was also necessary that from this last navigable point there should run roads linking north with south across the Thames. The road was not a wide one, for when the great cross for St. Paul's dome was cast at Mitcham there was not room enough for it to pass. But it was a road nevertheless, and from its marriage with the river all London has been begotten.See Walter Shaw Sparrow, A Book of Bridges; Christian Barman, The Bridge (1926) ; W. F. Watson, Bridge Architecture (1927) ; J. A. Waddell, Bridge Engineering (1916). (C. BA. ; X.) United States.—During the past century, the principal demand for bridge construction was in connection with the building of the railroad transportation systems. At the turn of the century, many of the railroad bridges were being replaced or reconstructed to provide increased strength and clearance for the rapidly increasing size, weight, and speed of locomotives and trains. Since about however, there has been no further extension of the rail sys tems, and the economic plight of the railroads has limited the improvement of existing construction. Instead, the phenomenal development of automobile traffic has created a new phase of bridge construction. From 8,000 automobiles in 1900 and 2,000, 000 in 1915, the number of automobiles and motor trucks in the U.S. has multiplied to 30,000,000 (194o). This rapidly increasing volume of highway traffic has resulted in a demand for more and better roads and express highways, with the accompanying neces sity for more and larger bridges ; and it has created both demand and economic justification for bridges of unprecedented dimen sions over crossings that previously had to be left unspanned.

For spans of unusual magnitude and cost, also for interstate and international crossings, toll bridges have come to be the solu tion of the financing problem. Up to 1929, most of these toll spans were built under private ownership, but the more recent toll bridges have all been built by public commissions or "bridge authorities." Toll bridges are financed, as a rule, by issuing revenue bonds which are secured only by the prospective earnings, so that the user pays for them until they become free, instead of adding them to the general tax burden. The motoring public has thus secured the benefit of many needed bridge crossings where such facilities would otherwise have remained unattainable. There were in 1940 over 400 toll bridges in the U.S., representing a total investment of over $500,000,000; only about 200, amounting to $100,000,000, were privately owned. There were over 90,00o steel bridges (not counting timber trestles) on 24o,000mi. of railroad in the United States in 1940. The aggregate length of these steel railroad bridges was over 1,50o miles. The number of highway bridges in the U.S. probably exceeds 250,000 (besides over 2,000, 00o culverts) on the 3,00o,000mi. of roads and highways. The aggregate investment in these highway bridges is over $3,000,000, 000.

Cities located at junctions of rivers are particularly dependent upon bridges for their development. The city of Pittsburgh has 18 highway bridges and 9 railroad bridges spanning the Alle gheny and Monongahela rivers. In New York city, in a single day, over 480,000 automobiles and trucks cross the highway bridges entering Manhattan island,-3oo,000 on 12 free bridges (including z oo,000 on the Queensboro bridge and 8o,000 on the Manhattan bridge), and 180,000 on 3 toll bridges (George Wash ington, Triborough, and Henry Hudson), besides over 2,000,000 passengers on rapid transit trains and electric trolley cars. The Henry Hudson bridge (toll) carries 13,000,000 autos a year.

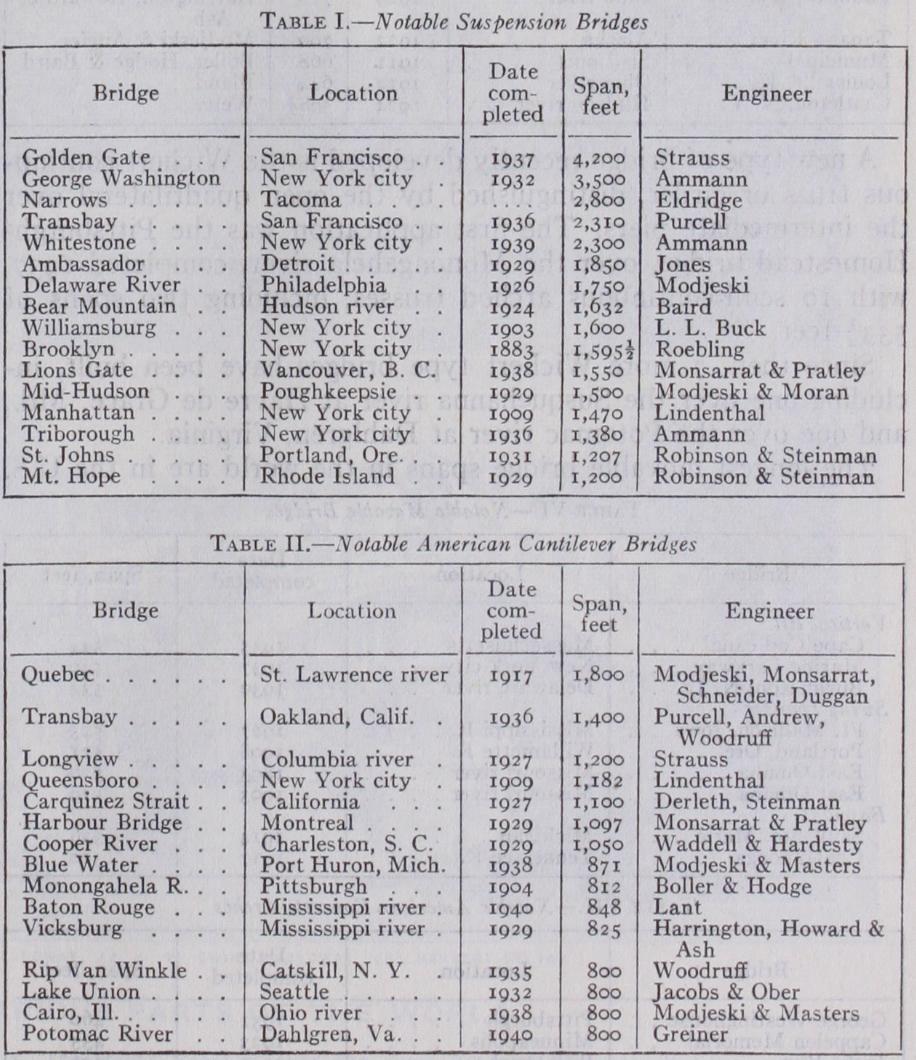

The six longest spans in the world are in the U.S. (Golden Gate, 4, 200f t. ; George Washington, 3, 500f t. ; Tacoma Narrows, 2,800f t. ; Transbay, 2,3i oft.; Bronx-Whitestone, 2,3ooft.; Detroit Ambas sador bridge, 1,850 feet). All of these have been completed or started since 1929, all are of the suspension type, and all are high way toll bridges. The largest bridge project in the world to date is the Transbay bridge between San Francisco and Oakland, com pleted in 1936, costing $77,200,000. Its total length of 8mi. in cludes two joined suspension bridges of 2,31 of t. main span each, a cantilever bridge of 1,400ft. main span, and other spans. A record foundation depth of 240f t. was reached for one of the piers. The world's longest span is the Golden Gate Bridge, also at San Fran cisco, completed in 1937 at a cost of $35,000,000. The main span, 2 2 of t. above the water, is 4, 200f t. between towers 746 f t. high. The two main cables are 361 inches in diameter, the largest con structed to date.

The George Washington bridge, spanning the Hudson river at New York with a main span of 3,500ft., was opened in 1932 at an initial cost of $6o,000,000. It has four main cables, each 36 inches in diameter. Provision is made for 8 lanes of highway traffic on the present deck and for the future addition of a lower deck.

It took 4o years (1889 to 192 9) to increase the world's record span length from 1,700ft. (Forth bridge) to 1,85oft. (Ambassador bridge at Detroit) ; then, in the next eight years (1929 to 1937), in two leaps (George Washington bridge and Golden Gate bridge), the record span length was more than doubled, from 1,85oft. to 4,200 feet. Plans have been prepared for the proposed Narrows bridge (suspension) to span the entrance to New York harbour with a record-breaking span length of 4,620 feet. A generation ago, the feasibility of a span of 3,000ft. was seriously questioned; now bridge engineers confidently agree that suspension bridge spans as long as ro,000ft. are practically feasible.

It is significant to note that the cantilever bridge has yielded its previously claimed supremacy to the suspension type. For spans exceeding 800ft., and even for shorter spans, the suspension type is generally adopted as preferable. Both aesthetic and eco nomic considerations have governed this change.

Early steel bridges of outstanding beauty are the Brooklyn bridge, the Washington Arch bridge over the Harlem river, and the Hell Gate Arch bridge. The most beautiful concrete bridges in the U.S. include the Ridge Road bridge, Rochester, N.Y.; Con necticut avenue bridge, Washington ; Walnut Lane bridge, Phila delphia; Raritan River bridge, New Brunswick, N. J.; Rocky River bridge, Cleveland ; Tunkhannock viaduct, Pennsylvania ; Colorado River bridge, Austin, Texas; Cappelen Memorial bridge, Minneapolis.

The 16 largest suspension bridges in the world are in the U.S.

and Canada. See TABLE I.

The Sky Ride at the Century of Progress Exposition in Chicago and 1934) was a suspension bridge of 1,850-ft. span, carry ing 12-ton passenger cars t. above the ground.

With one exception (Forth bridge, Scotland, 1,700-ft. span), the 27 largest cantilever bridges in the world are in the U.S. and Canada.

Of the 14 largest steel arches in the world, 9 are in the U.S.

Of the 6 largest concrete spans in the world, 3 are in the U.S.

The 20 longest-span simple truss bridges in the world are in the U.S. (including one in Alaska). (D. B. S.)