Broadcasting Technique

BROADCASTING TECHNIQUE Broadcasting technique necessitates some considerable additions to the bare essentials of a wireless telephone transmitter in order that the system may conform to the canons of the new art. The essential links in the chain between artist and listener can be classified as follows: (I) The microphone and its attendant amplifier. (2) The studio or place of origination of programme. (3) The "mixing" of artificial echo, "effects," incidental music, speech, etc., to combine to make a given impression upon the listener. (4) The central control room. (5) The land line or wireless link to enable programmes to be initiated at one point while radiated from another station or radiated simultaneously from several stations. (6) The broadcast transmitter. (7) The broadcast receiver. It will also be necessary to discuss (8) the distribution and power of the transmitters; (a) service area; (b) interference between the various broadcasting stations; (c) distribution for national systems. (A basic broadcasting system is shown diagrammatically in fig. I.) (I) The Microphone and Its Amplifier.—Every micro phone (called in America and by telephone engineers a trans mitter) relies for its action upon the sound waves causing a movement of some armature which, by such movements, gener ates electric currents in the microphone. The generation of current by armature movement may be involved by a change of capacity, a change of movement of a conductor in a magnetic field, or a change of resistance in a direct current circuit. The excel lence of a microphone may be judged in terms of its response characteristic, and its degree of background noise. The response characteristic of a microphone is measured firstly, as to its abil ity to give equal electrical response for equal sound wave pres sure at any frequency between the limits of the audible range; and secondly, as to its capacity to give, at any frequency, proportionality between input sound pressure and output elec trical response. Every microphone has an intrinsic background noise caused by the polarizing current or by the associated ampli fier valves, or by both these in combination. Microphones must be compared for background noise at a given sensitivity.

A perfect response characteristic must involve a complete absence of mechanical resonance within the range of frequency considered. This is not easy, as every armature tends to resonate at some (audible) frequency. Carbon and condenser microphones have been constructed with a view to eliminating resonance by using a diaphragm stretched to have a resonance above the audi ble limit. Carbon microphones have been used, notably one in vented by E. Reisz and developed by H. J. Round, in which the layer of carbon is thin enough to give resonance effects at fre quencies above audibility. Certain microphones have been developed (193o-1935) in which the armature is designed to be more sensitive to sound coming from one direction than from another. These have great usefulness in auditoria where back ground noises are liable to be strong compared with the sounds it is desired shall be broadcast. Thus for instance, when broadcast ing orchestras playing in restaurants or speeches made at banquets, a better balance is obtained by the use of these, so-called, direc tional microphones.

Broadcasting microphones having excellent response character istics are extremely insensitive compared with ordinary commer cial types (as used on ordinary telephones) in which resonance can be permitted, and their electrical output has to be amplified considerably before it can be used efficiently for transmission by telephone lines to a nearby control room or distribution centre. There may be ten or more studios in a broadcasting headquarters, and therefore the studios may be, even in the same building, a rela tively long way from the control room (q.v.) . The currents gen erated by the microphone are extremely feeble and therefore liable to be interfered with by induction from electric power and lighting circuits if long leads be used. Amplification is therefore divided into two halves, the A amplifier, located as closely as is convenient to the microphone, the output from which goes eventually to the B amplifier, situated in the central control room. The frequency characteristic of such amplifiers, i.e., their re sponse over the audible gamut, must be as even as possible. Connections between the amplifier and microphone and the amplifier and cable for connecting to the relatively distant con trol room or transmitter must be through transformers. Trans formers are necessary owing to the impossibility of matching the impedance of the output or input valve to the cable or micro phone. It is not easy to design a transformer giving an equal response over a frequency range of 200:1 (50 to I o,000 periods per second), but by the use of spaced windings and high permea bility iron, it has been proved by experience that a reasonably good characteristic curve may be obtained. (Figure 2 shows by means of a curve the frequency response of a good modern ampli fier.) (2) Place of Origination of Programme.—Broadcasting studio is the name given to the specially arranged room in which artists perform for broadcasting. It is of utmost importance to arrange for the acoustics of the studio to be as perfect as possible for its particular purpose. It is usually unwise, in the present condition of the art, to allow a large acoustical reverberation in the studio. In speech, when intelligibility is of primary im portance, it is necessary to use highly damped rooms. For music generally a greater amount of reverberation is desirable and even necessary, though a large orchestra and a quartet require different studio reverberation constants. As a practical basis it is best permanently to reduce the reverberation constant of the studio to something less than that required for most purposes and then, in some mechanical or electrical way, to add synthetic reverber ation. Changing the reverberation of the actual studios, where each may have to be used indifferently for all sorts of different performances, is not practical.

The usual way of reducing the reverberation of a room has been to cover the walls and ceiling with drapery, but, though this is satisfactory in principle, it is ugly and insanitary. The British Broadcasting Corporation and the National Broadcasting Com pany of America have made practical attempts to do away with drapery. The later B.B.C. studios have their walls covered with a hard paper backed by felt, while embrasures and deep bays prevent high acoustical frequency reverberations. A thick carpet covers the floor and the ceiling has movable draperies. The Ameri can organizations employ a form of aero concrete. In British practice artificial echo is introduced by using two microphones, one of which is connected through amplifiers direct to the trans mitter, whilst the other is connected through a separate amplifier to a loud-speaker installed in a room with a high degree of re verberation. The loud-speaker in this room faces a microphone, the currents from which are injected into the direct transmitter circuit. The amount of echo current from the echo microphone is directly controllable by a handle, and therefore the extent of superimposed echo may be varied conveniently according to the type of item being broadcast.

In Great Britain approximately 20% of the programme hours is supplied from outside sources, such as church services, public gatherings, theatres and restaurants, etc. In the case of the trans mission of a concert from an outside hall it is often found that the acoustics of the building are different from those of a studio, and the best results can only be obtained by experiment. As this is done at a rehearsal before the transmission it is necessary to estimate the changes in reverberation which will result when an audience is present. At the same time it is necessary to adjust the balance of the transmission by the relative placing of soloists, orchestra and microphone, so as to obtain a proper balance. The outside broadcast engineers install their apparatus, consisting of microphones and A amplifiers, wherever and whenever it is re quired. Connection to the distribution centre of the broadcast organization is made by land line. Where it is necessary for the microphone to be moving during the transmission, as in the case of a running commentary of the Oxford and Cambridge boat race, lines cannot, of course, be used, and connection has to be made to some stationary point by means of a wireless link. In this instance the A amplifier would be replaced by a low-power wireless transmitter the emissions from which can be received at some stationary point and the transmission then passed to the distribution centre.

(3) "Mixing..

The development of the dramatic programme, with attendant incidental music and effects, has necessitated the frequent use of several studios simultaneously. It is not feasible with small studios to concentrate artists, chorus, orchestra, effects, producers, etc., together; several studios must be employed, and the transmissions from each of these combined in a "mixing" room through which the outputs of all studios pass on their way to the central control room. Signalling circuits are installed be tween all studios and the mixing room, between the mixing room and the control room, and between the control room and all the studios. The outside broadcast circuits can also be led through the mixing room as it is sometimes required to superimpose external effects on a studio programme. The mixing room is also connected by a land line to a wireless receiving station and here any distant transmitting wireless station, permanent or tempo rary, may be picked up and re-broadcast over the normal national broadcast system.

(4) The Central Control Room.

At this link in the chain of transmission two definite functions are fulfilled; viz., that of adjusting the level of low frequency energy to modulate more or less the transmitter high frequency currents, and that of distrib uting the programmes to one or more transmitters, centres or listening points.The first of these functions, that of controlling the intensity of output to the local and other transmitters which are taking the programme, is necessary for the following reason : a brass band gives a volume of sound output hundreds of times greater than a person whispering or a distant nightingale; if the sensi tivity of the microphone or its amplifier were not varied, either the listener would never hear the nightingale or the brass band would vastly overmodulate the constant-power transmitter; dur ing the musical items, if the pianissimo passages were not ampli fied and the fortissimo passages not reduced a little on the ampli fier, an inferior sound picture would be rendered even on the best receivers.

The second stage of amplification in the broadcast chain is situated in the control room, and is known as the B amplifier, which is designed for variable sensitivity, and it is the duty of the "controller" continuously to control the intensity of the trans mission with the idea of giving to the listener the best possible sound picture of the original. A point on which much variety of practice and opinion exists is whether this control of volume should be in the hands of engineers or of artists. The advantage of the latter is that a score can be followed with a view to the anticipation of a forte passage and a consequent slight reduction in time to prevent over-modulation, and vice versa for the pre vention of under-modulation during pianissimo passages. The eye, and not the ear, must be the criterion for the accurate judg ment of the effects of controlling, and each "control" amplifier is equipped with two meters—one to show a maximum which must not be passed, the other to show the volume being radiated at any instant. It is necessary to have two instruments, because the permissible maximum for a given volume is not the same with different voices, instruments, studio acoustics, etc. In addi tion, the depth of modulation at every instant throughout the transmission is checked mechanically on a recording modulation meter to show up any faults due to the human element.

The second function of the control room is to provide a means of handling conveniently the distribution of the one or more programmes to those transmitters which are sharing the trans mission with the local station. In practice the problems of pro gramme building are simplified enormously by the ease with which stations can be made to exchange programmes and by the reduc tion to an absolute minimum of the time taken in making changes. The system depends on the use of a multiplicity of relays, ampli fiers, alarms, line terminal switching, etc. Finally, the engineer in charge of the control room is responsible for the maintenance of all transmission logs (in the case of the British system accurate to a second) and for the cutting and timing of the transmission generally.

(5) The Land Line and Wireless Link.—It is necessary to have as many stations as there are channels of free ether available. If an event or performance of nation-wide interest is to be broad cast it is necessary to allow all subscribers an equal chance of hearing. This is made possible by using telephone lines or cables to connect the point at which the event takes place, first to the nearest distribution centre in the broadcast system, and thence to all stations that require to take the programme. This is called simultaneous broadcasting in Britain, or chain broadcasting in the United States. All lines of great length introduce an impedance which varies with different frequencies. This means that a micro phone system giving a perfect response characteristic will, if connected to a long line, produce at the end of that line a dis torted output unless precautions are taken to equalize inherent distortions. There are in general two types of line—overhead and cable. The former is the familiar type suspended on porcelain insulators carried on poles, while the latter is buried in trenches. An inch diameter buried cable, for instance, may carry 1 so cir cuits. The overhead line would appear to introduce less distor tion than the cable because its distributed self-capacity is lower than that of the buried type. Cable can, however, be treated to give a good characteristic, i.e., less differing impedance to differ ent frequencies, by a system of loading. Light loaded cables, which are, however, more expensive, have characteristics suitable for broadcasting work.

The currents in any long line attenuate (steadily decrease as they proceed away from the original source) , but this effect is more rapid in the case of a cable than it is with open or overhead lines. This attenuation can, however, be overcome by the use of thermionic amplifiers placed at regularly spaced intervals along the line. These are called "repeaters" and the points at which they exist "repeater points," and such are extensively used in modern trunk telephone routes (see TELEPHONE). The Com mercial type of repeater, which enables a conversation in both directions to be raised in level, is both unsuitable and unnecessary for broadcasting. The broadcast repeater need only work in one direction, but must maintain an even response characteristic. Apart from the problem of at tenuation and the precautions which are taken to overcome it, every line will introduce some distortion by cutting down cer tain frequencies in favour of others. It is therefore essential to employ a frequency response correction by the termination of lines at repeater points and at their final terminations with a filter containing concentrated in ductance and capacity.

Owing to the fact that the cable cannot be used for connecting different continents separated by wide oceans, the "wireless link" should play a part in long range broadcasting. Stations using very high frequencies (15,00o to 7,500kc., 20 to 40m.) can be picked up over ranges equal to the maximum distances existing on the earth. Unfortunately the solution of the problem of sufficiently satisfactory reception for re-broadcasting purposes is incomplete ; there is not a guarantee of service on short waves although they offer possibilities for future success. Since 1923 America has sent out programmes from short wave stations which can be heard, conditions permitting, all over the world. Usually reception is too inferior to be compared to that existing with the national services from local stations though occasionally grammes from America have been re-broadcast in Britain. Early in the year of 1927 Holland started sending short wave sions which have been heard sporadically throughout the world. The British Broadcasting Corporation has erected a group of stations at Daventry which direct their several radiations over different great circle world paths with a view to giving a casting service particularly to the British Dominions and Colonies. (6) The Broadcast Transmitter.—The general principles and practice of wireless telegraphy and telephony transmission are dealt with in the articles WIRELESS TELEGRAPHY and TELEPHONE, and therefore discussion of this point will be confined to tials. The basic system of modulation for broadcasting mitters is known as "choke control." In this system the power plied to the oscillation generator, which generates the high quency currents in the aerial for radiation, is varied in sympathy with the amplified microphone currents by the action of control valves. As in the case of other links in the broadcast chain, the problem is principally one of achieving a perfect frequency and volume response characteristic, i.e., proportionality tween the limits of maximum and minimum modulation and an equal modulation at all frequencies for any given input volume. Economy in power, ease of maintenance or accessibility, and worthiness are also important factors. Two systems of modulation make use of choke control, the one modulating the aerial currents at high power and the other at low power. In the former (used almost exclusively, except by the German administration) the modulation system is in effect a low frequency power amplifier with sufficient power to modulate the aerial oscillations; in the latter, modulation takes place at low power, whereafter a high frequency amplifier increases the power of the modulated high frequency currents to the desired value. The British Broadcast ing Corporation uses low power modulation in all their regional stations except the Droitwich long wave station (1935) which uses a system of high-power modulation. Fig. 5 shows the frequency response characteristic of that station which has an aerial power of i4okw. In Germany a system is employed in which modula tion is achieved by an alteration of the constants of the grid circuit of an oscillation generator. High-power modulation is in use in practically all other countries, such as America, France, Sweden, Den mark, Italy, Spain, etc., while some cen tral European States use the German grid system as well for different stations.

Most antennae systems for a modern installation are half wave-length aerials supported on steel towers. A single tower having a height of half the wave length employed is sometimes used as the aerial. The Budapest aerial is the tallest structure in Europe, approxi mately i,000ft. high. Modern technique mostly employs aerials located 20 to iooft. from the transmitter build ings, the power output of oscillations be ing fed to the aerial via a two-wire feeder. This increases the radiation qualities of the aerial and has no compensating disad vantage.

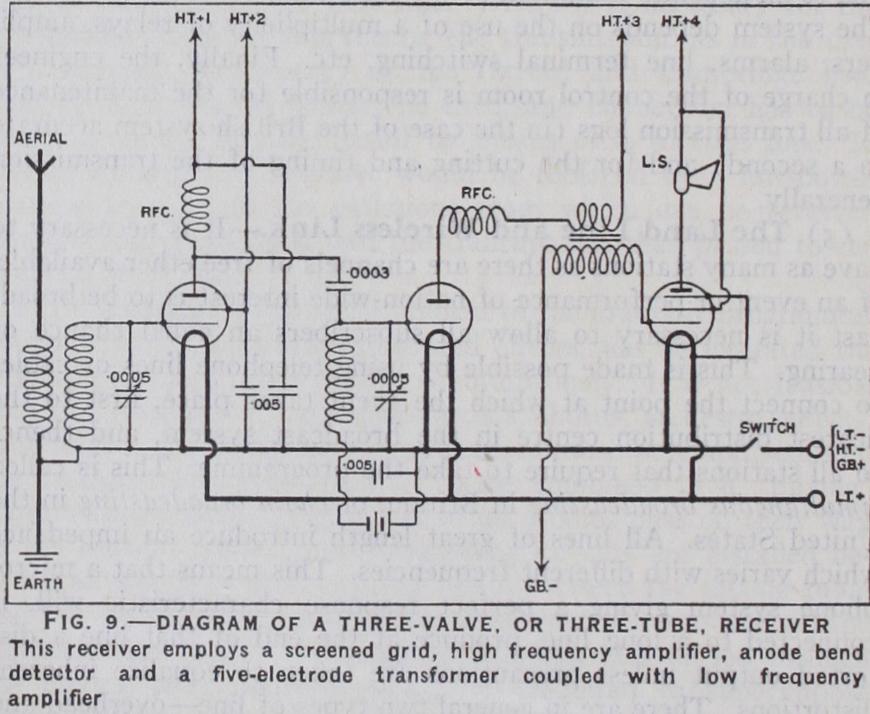

(7) The Broadcast Receiver.—Broadcasting receivers may be of the valve or crystal type. The valve set requires the in stallation of some power supply, and is essential in areas of weak signal strength or in areas of normal signal strength where only small aerials can be erected or anywhere for loud-speaker use. (Reference should here be made to figs. 8, 9 and ro, giving crystal 3-valve and 5-valve lay-outs.) Development in receiving sets has taken two paths. The rare high fidelity product has concentrated upon obtaining a wide fre quency-response characteristic and a large undistorted power out put almost regardless of cost. Often as much as r o watts power is available to energise the loud speaker. The ubiquitous receiver has been developed more and more with a view to reducing its re tail price and increasing both its sensitivity and selectivity with the object of "bringing in" as many stations as possible. The great increase of both the power and the number of stations working in Europe has forced the designers of typical receivers to narrow the band width of response in order to select the wanted station's transmissions free from interference by other stations. The latter development has been necessarily accompanied by a degradation of the quality of music obtainable. The reduction of price has vastly increased the sales of this type of instrument. A large mar ket has been found for the "all mains" set which, where public supply current is available, is energised entirely from the mains and does not require the use of batteries. Battery and crystal sets are however still widely used, the former because many houses are not supplied with electric power, the latter still maintaining its popularity because of the satisfying quality of headphone music and, perhaps more, because of its reliability, simplicity and cheapness.

The design of good loud-speakers proceeds apace and some excellent types are available. It should be remembered that no loud-speaker can give good quality if its input is limited or dis torted by the receiver. The basic technical problem is to obtain conditions of transmission allowing the listener to obtain good quality reproduction and a choice between different types of pro grammes. In America, where ten or more stations, separated by only, say, 3o to 5okc., may have practically equal field strengths over an area, some extremely selective receivers have been produced, but their ability to eliminate many stations in favour of one is often only achieved by depreciating the fre quency response. It most European countries where distribution in thickly populated areas has been on a single programme basis, the development of high selectivity without a loss in the quality of reproduction has been retarded. This has permitted greater freedom in the design of high frequency circuits, and the response characteristics which are obtained are excellent. The ideal re ceiver should produce a square resonance curve 2okc. wide, mov able as a whole, without loss of its shape or change in width, over the required frequency gamut of all broadcasting stations. This movement and all other adjustments should be operated simul taneously by one handle, the receiver being efficiently energized from the electric supply.

(8) The Distribution and Power of the Transmitters.— (a) Service area. It is necessary to ensure that the programme shall suffer no interruption from extraneous electric waves from what soever source. As the distance between the listener and the broad cast transmitter is increased so will the liability to interruption be increased ; i.e., as the receiver is located further and further away from a station, the ratio of the required signal to the un wanted interference becomes less and less. This ratio is not a function of the type of aerial nor the type of receiver used by the listener, because if more amplification is used both the dis turbances and the broadcast signal are each proportionately in creased. If radiation is perfectly symmetrical around a broad casting station then the rate of decay, or attenuation, of signal strength is equal along any line drawn from the transmitter. Thus an area may be enclosed by a circle within which the signal strength is greater than a certain amount. By common experience in the regular reception of signals of various field strengths, it is possible to estimate service ranges in terms of degree of inter ruption. Service areas have been defined arbitrarily in terms of field strength, as follows : Boundaries in Millivolts per metre (a convenient method of Service Area expressing strength of signal) "Wipe-out" Over 3o mv. per metre A „ ro B ,, 5 C ,, )) ,7 7I These definitions of service area have been accepted and adopted by the technical committee of the Union Internationale de ophonie. Within a "wipe-out" area uninterrupted service can be uaranteed, unless the interference is produced by listeners them selves producing oscillations in their receiving aerials. There will be difficulty in a wipe-out area in "cutting out" the local station in order to receive more distant and weaker transmissions from other stations. In an "A" service area very little interruption will exist even in large towns where extensive use is made of electrical apparatus likely to cause a disturbance. In a "B" service area there may be, in a minority of cases, some interference. Crystal reception is possible with good equipment up to the outer bound aries of a "B" service area. In a "C" service area amplification by valve receivers is essential, and some interruption, depending upon local conditions, is highly probable.

No service area, whatever the power of the station, can be much greater than i oo miles radius, when using frequencies of the order of 1,500 and 5ookc. (200 to 600m. wave-length), owing to wide variations of received signal strength after nightfall. This varia tion of signal strength is called "fading" or "night effect." Fading is believed to be due to the existence of a ray from the broad casting station which does not travel directly over the earth's sur face, but travels upwards and is then bent down from an electri fied layer (called the Kennelly-Heaviside layer) in the upper atmosphere. This indirect ray does not remain constant, owing to the momentary variations of the refractive power of the electrified layer ; and for this reason the listener has to contend with a con stantly changing signal strength which ruins the musical value of the programme. The listener must in fact depend for service upon the direct ray which can only outbalance the reflected ray at distances which are, in practice, seldom greater than ioo miles.

For any given radiated power the extent of service area is affected by three variables : frequency of wave emitted (and therefore wave-length), type of ground around a station and what is found upon it (trees, houses, etc.), and type of transmitting aerial. The higher the frequency the more quickly the direct ray waves attenuate. The use of longer wave-lengths might appear advisable as the waves are less attenuated and the service area for a given power greatly increased. This is true, but the longer the wave-length the fewer the channels available in a given wave length gamut. For instance, there are 5o channels in the wave band of 200 to 3oom., and only one channel in the band of 1,500 to 1,60o metres. The situation with regard to interference by all the users of aether is so serious that very few "long" wave-length channels are available for broadcasting, and at the Washington Conference of 1927 only six channels were allotted for the use of broadcasting transmitters. The provisions of the Washington conference regarding long-wave broadcasting were largely ignored in Europe. The Madrid conference (193 2) decided to allocate waves between 1,00o and 2,000 metres for European broadcasting services. The ideal system of producing extensive service areas relies upon a combination of long and medium waves. If no other wireless services required the use of the aether, waves of fre quency 1,500 to i,000kc. would be used for low power local serv ices, from 1,000 to 5ookc. for regional broadcasting, and from 500 to 2ookc. for national broadcasting.

When waves pass over water, or wet, treeless and unpopulated ground, they do not attenuate so quickly as when they pass over ground covered by forests or towns. In fig. 6 a field strength con tour map is shown, giving the result of observations for the Lon don station, 2L.O. It will be remarked that the service area is anything but circular, and that listeners, living at equal distances from the transmitter but in different directions from it will not receive the same strength of signal. This is caused by the differ ence in attenuations in different directions, due to the various types of obstacle over which the signal passes. Fig. 7 is a family of curves showing the attenuation of field strength when r kw. power is radiated at different frequencies over average English pastoral country.

(b) Interference Between Stations. Every broadcasting sta tion operates by the modulation of electric waves sent out from its antennae. A more exact mode of expression would be to say that waves are sent out at a frequency N,,,, and have added and subtracted from them waves of frequency , where N,, is the carrier wave and N,,, the modulated wave frequency. Thus a com plex disturbance Now+Nm and is radiated. Expressing this numerically, if a note of i,000 periods per sec., e.g., a note of a violin, is to be radiated and the carrier wave frequency is one million, then there are radiated out into the aether waves of fre quency one million, one million plus a thousand, and one million minus a thousand. It is the function of the receiver to detect the production of beats by these frequencies so as once more to pro duce the note of a thousand in the telephones or loud-speakers. The added and subtracted waves are called side bands. As it is desired to reproduce frequencies up to a maximum of io,000 cycles per second (i okc.) each broadcasting transmitter occupies effectively a frequency spectrum within the aether of 2okc. or 1 okc. each side of the carrier wave frequency. If therefore a second station has the frequency of its carrier wave separated by less than 2okc. we should expect the side bands of one to inter fere with the side bands of another. This assumes, theoretically, that frequency space must be left for the accommodation of two simultaneous 1okc. side bands in order that they shall not com bine to produce less than a further 1 okc. frequency.

At the Washington Conference of 1927 it was agreed by the Governments to allocate a frequency band for broadcasting from 1,5ookc. per sec. to about S5okc. per sec. (loom. to 545m•) This means that with 3okc. separation between stations, about 30 channels exist for the exclusive use of all the broadcasting organi zations. It might be expected that such a number of available channels could be increased by duplication because of the large geographical distance between stations. This is partly true, but even if stations as much as 3,00o miles apart are not separated in frequency by a minimum of 1okc. interference will result during hours of darkness and service areas will be reduced. This means that there exists room for approximately 95 medium-frequency stations if each is to be assured moderately free aether. In the lower frequencies 64kc. have been allocated, giving room for an additional six to seven stations only. It will be appreciated that relatively few channels exist for all the European broadcasting stations, numbering 300 or more.

A solution to the problem has been attempted in Europe by the technical committee of the Union Internationale de Radiophonie which represents approximately 8o% of the broadcasting organi zations of Europe. A plan was drawn up which gave, of the channels existing, a certain number for the exclusive use of each nation. The allocation of this number was based upon the area, population and "intellectual and commercial importance" of each nation, the latter factor being calculated upon the number of telephone calls made and telegrams sent in a given year in each country. It was found that there existed far more stations than frequencies. A certain number of frequencies therefore were classified as non-exclusive, to be shared by stations far apart in geographical distance. Such stations have to be content now to give a purely local service, as their service areas are seriously diminished by interference from the other stations with which they share channels. The remaining frequencies were allotted "exclusively" to particular nations for the use of their more important stations, whether such stations were already existing or contemplated. In spite of formal acceptance in 1926, many nations had not by the end of 1927 carried out their part in the readjustment, and conditions were little improved. By 1935 com parative stability was reached; but the crowding of stations limits good quality reproduction to a strictly local station.

(c) Distribution for National Systems. Broadcasting has grown up in a somewhat haphazard way and knowledge has come in terms of actual experience. So far, all nations have realized that many stations of fairly low power give the most uniform distri bution of service area. The system of distribution now existing in Britain is typical of most countries where the responsibility for providing a national service has been vested in one authority. It was built up first by the erection of eight main stations for the service of the principal towns and districts. These stations had "C" service areas of only about 3o miles radius, and therefore left much of the country, urban and rural, almost unserved. Other urban areas were filled up by smaller stations. These small stations are known as relay stations because they are linked by land line to some central studio and repeat the programme of a main station. (With a limited income it is not wise unduly to dilute programme revenue, otherwise variation in mediocrity alone results.) The main and relay stations brought practically all urban areas within a "B" service area, and consequently the rural areas only remained uncovered. This was done by one high-power station working on a lower frequency and, with the assistance of the other stations, 8o% of the population were brought within the "B" service area of one programme. This involved the use of 21 channels.

This system of distribution was of relatively rapid growth in England as compared with other contemporary organizations and, being temporarily adequate, caused over two million listeners to subscribe to the service. During the years 1926 and 1927 the number of European stations rapidly increased and with their expansion the mutual interference between stations became more serious on account of the limited number of channels available. The once sufficient national distribution was so restricted by in terference that it became necessary to build afresh, but with fewer stations of higher power and giving a greater service area per channel.

In countries, such as France and Spain, where private enter prise alone, chiefly or in part, provides the broadcasting service, stations are found grouped round urban areas and rural areas are comparatively neglected. This is a very obvious develop ment since the stations are supported by advertisement revenue and therefore require to compete with others by covering densely populated areas. Nevertheless the problem of free aether is as acute in the United States as it is in Europe, and the policy which would allow the high-power station to seize for itself what aether it requires, resulting in the consequent survival of the richest organization, is an undesirable solution.

In Britain a scheme, called the regional scheme, has been framed to be gradually put into practice from 1928 onwards. The essential feature of this new scheme of distribution is the use of few, but high-powered, stations so designed and sited as to give a choice of two programmes to the maximum number of listeners. By locating two high-power transmitters at the same point their service areas are made almost coincident so that, given adequate separation between their carrier frequencies, everyone within their service areas has an equal facility for the reception of both programmes. A method of minimizing interference is to work two stations on exactly the same carrier wave frequency. Re searches on this subject made by the B.B.C. from 1926 to 1923 show that, in spite of the fact that the carrier and side bands of each station must interfere, nevertheless good service results from one station at the points where its field strength is greater than five times that of the other sharing its wave, provided each station transmits the same programme. This should allow some economies in aether channels. Already America, Sweden, Germany and Great Britain have made attempts to place such a scheme into practical operation. (P. P. E.) See L. B. Turner, Wireless Telegraphy and Telephony (1921) ; W. Greenwood, Text-Book of Wireless Telegraphy and Telephony (1925) ; A. H. Morse, Radio: Beam and Broadcast, its Story and Patents; J. Lawrence Pritchard, Broadcast Reception in Theory and Practice (1926) .