Brocade

Loading

BROCADE, the name usually given to a class of decorative textiles enriched on their surface with weavings in low relief, of which the floating threads at the back hang loose or are cut away.

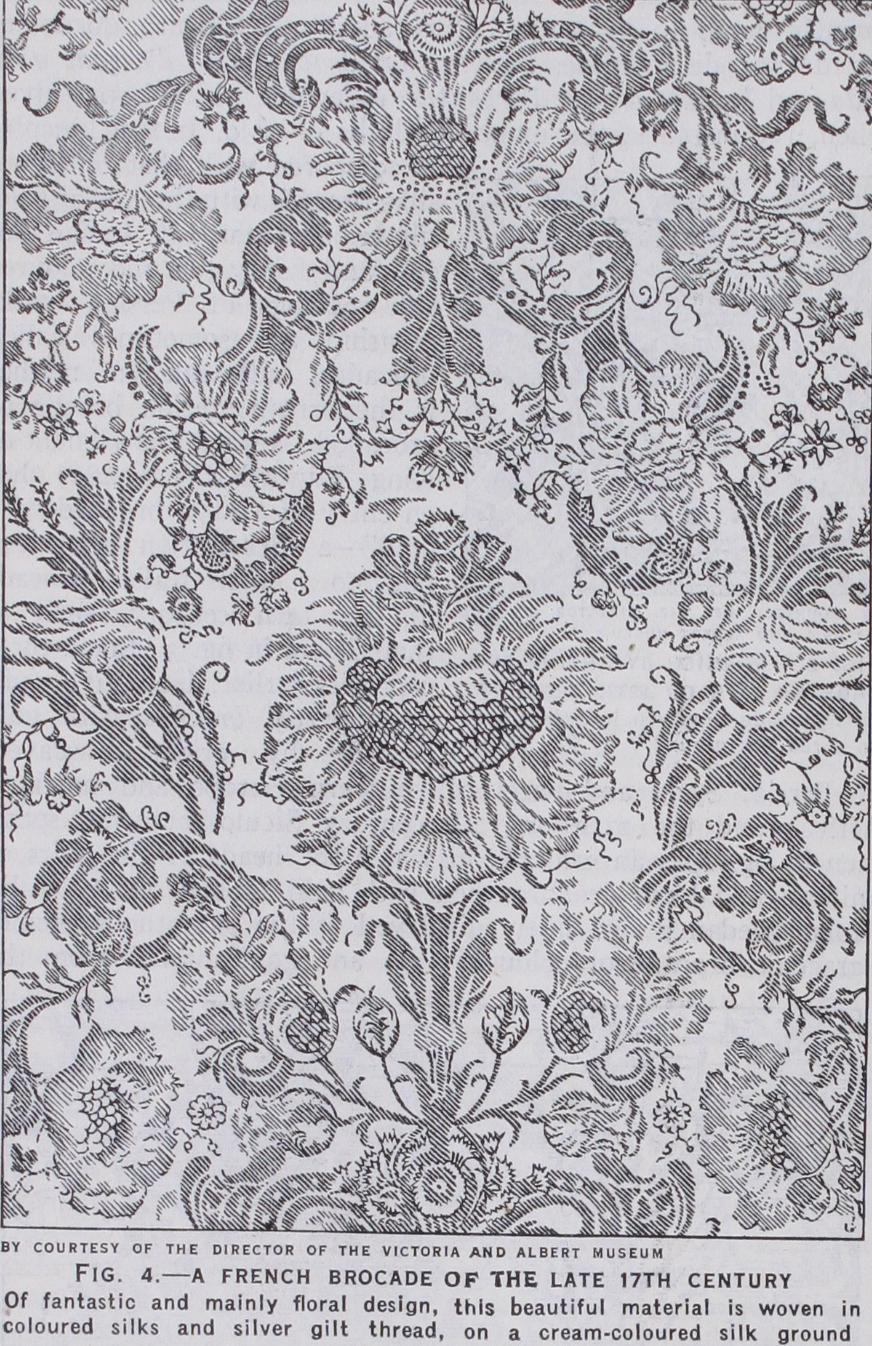

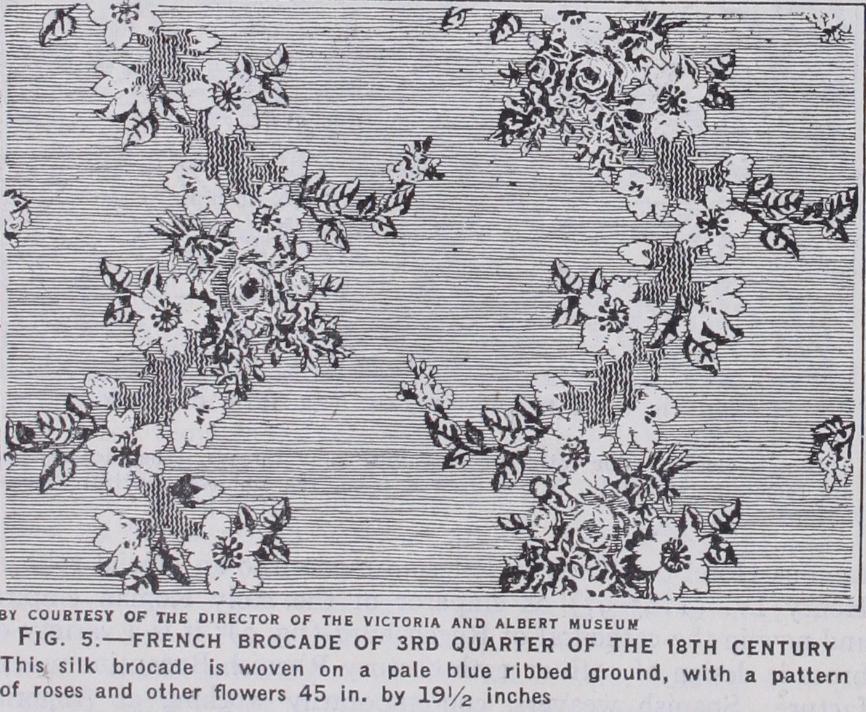

The Latin word

broccus is related equally to the Italian brocato, the Spanish brocar and the French brocarts and brocher, and plies a form of stitching or broaching, so that textile fabrics woven with an appearance of added stitching or broaching have quently come to be termed "brocades." A Spanish document dated 1375 distinguishes between los drops d'or e d'argent o de seda and brocats d'or e d'argent, a difference which is perceived when, for instance, the make of cloths of gold, Indian kincobs, is compared with that of Lyons silks broches with threads of gold, silk or other material. Indian cobs and dainty gold and coloured silk-weavings of Persian manship are sometimes called brocades, although in neither is the ornamentation broche or brocaded. A wardrobe account of King Edward IV. (148o) has an entry of "satyn broched with gold"—a description that plies to a north Italian brocade of the 14th century, such as that shown in fig. 3. Some three centuries earlier, decorative stuffs were partly broches with gold threads by oriental weavers of Persia, Syria and parts of southern Europe and northern Africa; and the 11th or 12th century Siculo-Saracenic men in fig. I, is an example in which the heads of the pairs of animals and birds are broached with gold thread. Of typically Mohammedan design finely displayed, is the sumptuous Saracenic brocade of coloured silks and gold threads from the famous Hotel des Tiraz in Palermo made into an official robe of Henry IV. (1165-97) as emperor of the Holy Roman empire, and now in the cathedral of Regensburg (fig. 2) ; it is a variety of brocade design of 12th or 13th century Rhenish-Byzantine manu facture. Spanish weavers, contemporarily working at Almeria, Malaga, Grenada and Seville used corresponding designs. In the 14th century the making of satins heavily brocaded with gold threads was associated conspicuously with such Italian towns as Lucca, Genoa, Venice and Florence. Fig. 3 is from a piece of 14th century dark-blue satin broched in relief with gold thread in a design similar to that in the background of Orcagna's nation of the Virgin," now in the National Gallery, London. Dur ing the 17th century, Genoa, Florence and Lyons vied with each other in making brocades. Fig. 4 is of a piece of French brocade of late 17th century, and fig. 5 is from a more simply composed design, in which the brocading is done with coloured silks only. During the 18th century Spitalfields competed with Lyons in manufacturing many sorts of brocades, specified in a collection of designs preserved in the art library of the Victoria and Albert museum in London, as "brocade lustring, brocade tabby, brocade tissue, brocade damask, brocade satin, Venetian brocade, and India figured brocade." Brocading in China seems to be of considerable antiquity, and Dr. Bushell in his valuable handbook on Chinese art cites a notice of five rolls of brocade with dragons woven upon a crimson ground, presented by the emperor Ming Ti of the Wei dynasty, in the year A.D. 238, to the reigning empress of Japan; and varieties of brocade patterns are recorded as being in use during the Sung dynasty (96o-127g). The first edition of an il lustrated work upon tillage and weaving was published in China in 1210, and contains an engraving of a loom constructed to weave flowered-silk brocades such as are woven at the present time at Suchow, Hangchow and elsewhere. Although described usually as brocades, certain specimens of imperial Chinese robes sumptu ous in ornament, sheen and the glisten of golden threads, are woven in the tapestry-weaving manner and without