Bryophyta

BRYOPHYTA, the botanical name of the second great sub division of the vegetable kingdom. The plants in this group are all small, some, indeed, so minute that only the most care ful observer is aware of the great variety of form and structure shown by them. It is quite common for liverworts, mosses, and even small plants of much higher groups to be indiscriminately classed together and popularly called "mosses." The Bryophyta do, however, form a well-defined class, easily recognizable with a little care, and it is equally easy to distinguish the broad sub groups into which they naturally fall. Their study necessarily entails minute observation, yet such observation shows them to be of great scientific interest, presenting as they do a special type of life history and affording in some of their groups graphic evidence of their evolutionary trend in spite of the complete absence of reliable evidence from fossil remains of any antiquity.

Speaking generally, Bryophyta grow only under moist condi tions, being commonly found along the sides of ditches, banks of streams and similar places. Some can certainly grow in even what would appear to be quite dry situations, though it would be more correct to say that such forms can exist through more or less prolonged dry periods, but grow actively only when conditions are comparatively moist. Even fewer are those forms which can thrive only in or on water. Liverworts and mosses are widely distributed throughout the world and with careful search it is possible to find representatives of a wide range of forms in almost any district. Usually they occupy a subordinate place in the general vegetation but occasionally, as with bog-mosses and some arctic mosses, they dominate the vegetation.

General Structure.

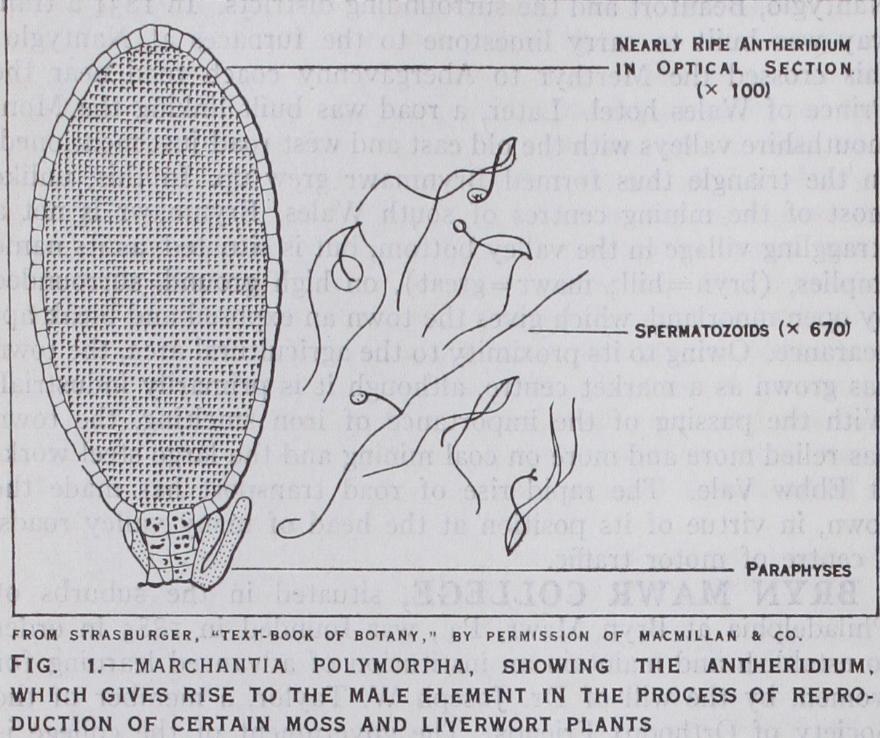

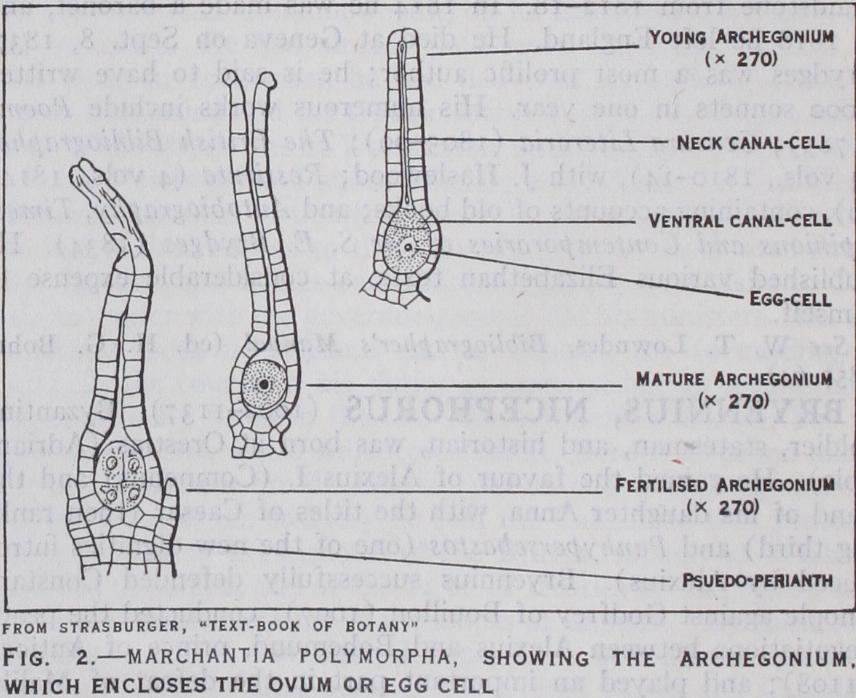

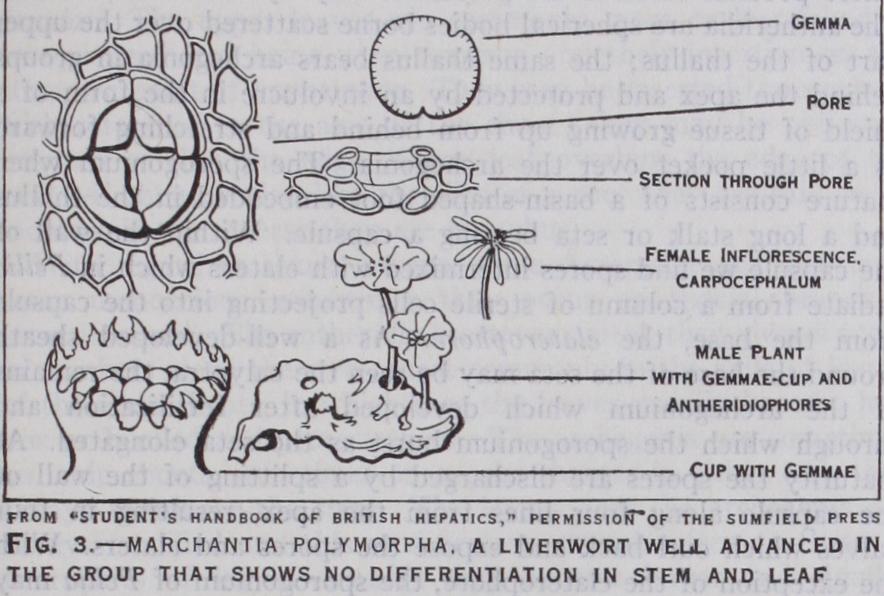

Mosses and most liverworts, amidst all their variety of form, are similar in so far as the plant as we see it consists of a stem bearing leaves (see figs. 7, II). Some liverworts show no differentiation into stem and leaf, but appear as flat structures closely pressed to the substratum on which they grow (figs. 3, 4). Such a habit we describe as thalloid; the plant is a thallus (i.e., a structure showing no differentiation into leaf and stem) in contradistinction to the leafy shoot of the remain ing liverworts and mosses ; though few in number of forms, those with this thalloid habit are very widely spread and are exceedingly interesting and significant in their form and struc ture. The small leafy shoot or thallus, as we see it, is self supporting, possessing chlorophyll as do other plants and rhizoids —elongated cells resembling root hairs which grow from the underside of the plant and not only attach it to the soil but con vey necessary salt solutions therefrom. Most interesting of all is the fact that the liverwort and moss plant bear the repro ductive organs called antheridia and archegonia. The antheridium when mature has a shorter or longer stalk supporting a spherical or more usually an ovoid body which consists of a wall of flattened cells enclosing a densely packed mass of very small cubical cells (fig. 1). In all cases examined, each of these cubical cells gives rise by division to two motile bodies called spermatozoids and functioning as the male element in sexual reproduction. Each spermatozoid consists of a more or less spirally coiled, club-shaped body, pointed at its anterior end and bearing there two long cilia whose movements are responsible for the motility of the sperm. These spermatozoids are liberated from the antheridium by de generation of the walls enclosing them. The archegonium also usually has a stalk and takes the form of a minute, long-necked flask (fig. 2). The wall of the flask consists of a layer of cells enclosing the ovum or egg-cell, the ventral canal cell and a row of neck canal cells. The ovum or egg-cell, the female element in sexual reproduction, occupies the lower part and most of the space of the body of the flask, the remaining upper part being occupied by the ventral canal cell, whilst the space within the neck of the flask is filled by a row of cells, the neck-canal cells, the whole being closed by a lid of cells continuous with those of the wall. When mature the lid is burst open by the mucilaginous degeneration of the neck-canal and ventral-canal cells, and fer tilization is brought about by the passage of the motile spermato zoids via the mucilage to the egg-cell. In all probability the spermatozoids are attracted to the open neck of the archegonium by some chemical stimulus; in any case one spermatozoid fuses with the egg cell and fertilization is brought about. The antheridia and archegonia arise by division of a single cell, and though almost identical in mature form throughout liverworts and mosses, the development differs in detail in the two groups. These differences may be found in literature cited in the bibliography.The fertilized ovum, two nuclei fused together, is the beginning of a new and very different stage in the life-history of these plants. This stage when completely developed varies considerably in structure in the various groups, but in general terms we may say that it consists of a capsule containing spores, sometimes borne upon a stalk, and throughout its whole life borne upon and nourished by the plant on which it arose (see figs. 4, I I) . In spite of the variation in structure, the end of this stage of the life-history is in all cases the production of spores which are shed and germinate in course of time. In mosses the spore gives rise to a branched filament of cells, the protonema, upon which the new moss plant arises. In liverworts a protonema is scarcely recognizable, the spore growing directly into the new plant.

Life-History.

Here then, as in all plants higher in the scale of botanical classification, the life-history is divisible into two stages which follow each other with regular alternation. The plant as we see it in the field begins its life with the spore, eventually produces antheridia and archegonia and ends that stage when a spermatozoid fuses with an ovum. This stage we call the gametophyte. The second stage begins with the fertilized ovum, develops into a capsule sometimes stalked, and attached to the gametophyte by a foot—the whole structure being called a sporo gonium—and ends with the production of spores. This stage we know as the spore-bearing stage or sporophyte. The life-history of a liverwort and moss then consists of the regular alterna tion of gametophyte and sporophyte. In this life-history the interest lies in the fact that the plant as we see it is the gameto phyte, the sporophyte dependent upon it and commonly recog nized as the moss "fruit" being the subordinate phase in this sense. In all other plants higher in the scale of evolution, the reverse is the case, the independent self-supporting plant is the sporophyte, the gametophyte being the subordinate partner in the life cycle, and though not always dependent upon the sporo phyte, always comparatively inconspicuous (see PTERIDOPHYTA and CYTOLOGY for discussion of the fundamental nuclear differ ence between haploid gametophyte and diploid sporophyte).

The Bryophyta, according to their form and structure, can be subdivided into the Hepaticae (liverworts) and Musci (mosses).

Further, the Hepaticae are clearly divisible into three smaller groups, the Marchantiales, Jungermanniales, and Anthocerotales, whilst the Musci also fall into three well-marked groups, the Sphagnales, Andreaeales, and Bryales.