Roman Britain I

ROMAN BRITAIN I. The Roman Conquest.—The conquest of Britain was un dertaken by Claudius in A.D. 43. Two causes coincided to pro duce the step. On the one hand a forward policy then ruled at Rome, leading to annexations in various lands. On the other hand, a probably philo-Roman prince, Cunobelin (known to literature as Cymbeline), had just been succeeded by two sons, Caratacus (q.v.) and Togodumnus, who were hostile to Rome. Caligula, the half-insane predecessor of Claudius, had made in respect to this event some blunder which we know only through a sensational exaggeration, but which doubtless had to be re trieved. An immediate reason for action was the appeal of a fugi tive British prince, presumably a Roman partisan and victim of Cunobelin's sons. So Aulus Plautius with a singularly well equipped army of some 40,000 men landed in Kent and advanced on London. Here Claudius himself appeared—the one reigning emperor of the 1st century who crossed the waves of ocean— and the army, crossing the Thames, moved forward through Essex and captured the native capital, Camulodunum, now Colchester. From the base of London and Colchester three corps continued the conquest. The left wing, the Second Legion (under Vespasian, afterwards emperor), subdued the south; the centre, the Four teenth and Twentieth Legions, subdued the midlands, while the right wing, the Ninth Legion, advanced through the eastern part of the island. This strategy was at first triumphant. The low lands of Britain, with their partly Romanized and partly scanty population and their easy physical features, presented no obstacle. Within three or four years everything south of the Humber and east of the Severn had been either directly annexed or entrusted, as protectorates, to native client-princes.

A more difficult task remained. The wild hills and wilder tribes of Wales and Yorkshire offered far fiercer resistance. There followed 3o years of intermittent hill fighting (A.D. 47-79). The precise details of the struggle are not known. Legionary fortresses were established at Wroxeter (for a time only), Caerleon (per haps not till near the close of the period) and Chester, facing the Welsh hills, and at Lincoln in the north-east. The method of conquest was the erection and maintenance of small detached forts in strategic positions, each garrisoned by 500 or i,000 men, and it was accompanied by a full share of those disasters which vigorous barbarians always inflict on civilized invaders. Progress was delayed too by the great revolt of Boadicea (q.v.) and a large part of the nominally conquered lowlands. Her rising was soon crushed, but the government was obviously afraid for a while to move its garrisons forward. Indeed, other needs of the empire caused the withdrawal of the Fourteenth Legion about 67. But the decade A.D. 70-80 was decisive. A series of three able generals commanded an army restored to its proper strength by the addition of Legio II. Adiutrix, and achieved the final sub jugation of Wales and the first conquest of Yorkshire, where a legionary fortress at York was substituted for that at Lincoln, The third and best-known, if not the ablest, of these generals, Iulius Agricola, moved on in A.D. 79 or 8o to the conquest of the farther north. He built forts in Cumberland, constructed a road (the Stanegate) from Carlisle to Corbridge, and pushed on across Cheviot into Scotland, where he established between the Clyde and Forth a temporary frontier, guarded by a line of posts, the most certainly identifiable of which is that at Bar hill. Presently he advanced into Caledonia and won a "famous vic tory" at Mons Graupius (sometimes, but incorrectly, spelt Gram pius), the site of which is doubtful, though it has given to the world the modern name of the Grampian hills. He dreamt even of invading Ireland, and thought it an easy task. The home government judged otherwise. Jealous possibly of a too brilliant general, certainly averse from costly and fruitless campaigns and needing the Legio II. Adiutrix for work elsewhere, it recalled both governor and legion, while it still endeavoured to cling to the ground that had been won (see CALEDONIA).

Precisely what happened after Agricola's departure, no one can tell. For 3o years (A.D. 85-115) the military history of Brit ain is little better than a blank; though we know that it was troubled. When the mists clear, we are in an altered world. About 115 or 12o the northern Britons rose in revolt and de stroyed the Ninth Legion, posted at York, which would bear the brunt of any northern rebellions. The land beyond Cheviot was lost. In 122 the second reigning emperor who crossed the ocean, Hadrian, came himself to Britain, brought the Sixth Legion to replace the Ninth, and introduced the frontier policy of his age. For over Tom. from Tyne to Solway, more exactly from Wallsend to Bowness, he built a continuous rampart, with a ditch in front of it, a number of small forts along it, one or two outposts a few miles to the north of it, and some detached forts (the best-known is on the hill above Maryport) guarding the Cumberland coast beyond its western end ; to move all these it must have been necessary to reduce the garrisons further south. The details of Hadrian's work are imperfectly known, for though many remains survive, it is hard to disentangle them. But that he has the best title to be regarded as the builder of the wall is proved alike by literature and by inscriptions. The meaning of the scheme is equally certain. It was to be, as it were, a Chinese wall, marking the definite limit of the Roman world. It was now declared, not by the secret resolutions of cabinets, but by the work of the spade marking the solid earth for ever, that the era of conquest was ended.

But empires move, though rulers bid them stand still. Whether the land beyond Hadrian's wall became temptingly peaceful or remained in vexing disorder, our authorities do not say. We know only that about 142 Hadrian's successor, Antoninus Pius, acting through his general Lollius Urbicus, advanced from the Tyne and Solway frontier to the narrower isthmus between Forth and Clyde, 36m. across, which Agricola had fortified before him. Here he reared a continuous rampart with a ditch in front —fair-sized forts, probably 19 in number, built, as a rule, so as to abut directly upon it—and a connecting road running from end to end. An ancient writer states that the rampart was made of regularly laid sods. Excavation has proved that this is true so far as the greater part of it is concerned, but that for 1 om. at the eastern end the body of the structure con sisted largely of clay. The work still survives visibly, though in varying preservation, except in the agricultural districts near its two ends. Occasionally, as or Croyhill (near Kilsyth), at Seabegs wood, and in the covers of Bonnyside (3m. west of Falkirk), wall and ditch and even road can be distinctly traced, while the sites of many of the forts are plain to practised eyes. Six of these forts have been excavated. All show the ordinary features of Roman castella, though they differ more than one would expect in forts built at one time by one general. In every case the barrack-rooms were of wood, and the headquarters buildings, the storehouses and the baths of stone. In size the enclosures range from just over one acre to just under seven. Nor was the character of the defences uniform. Balmuildy and Castlecary were walled with stone, whereas the ramparts of old Kilpatrick, Bar hill, and ,Rough castle were of sods, those of Mumrills of clay. Rough castle is remarkable for the astonishing strength of its ramparts and ravelins, as well as for a series of defensive pits, reminiscent of Caesar's lilia at Alesia, but which may belong to an earlier Agricolan fort. They were plainly intended to break an enemy's charge, and were either provided with stakes to impale the assailant or covered over with hurdles or the like to deceive him. Besides the 19 forts on the wall, one or two outposts seem to have been held at Ardoch and elsewhere along the natural route which runs by Stirling and Perth to the lowlands of the east coast.

The new frontier was reached from the south by two roads. One, known in mediaeval times as Dere street and misnamed Watling street by modern antiquaries, ran from Corbridge on the Tyne past Otterburn, crossed Cheviot near Makendon camps, and passed by an important fort at Newstead near Melrose, and others at Inveresk and Cramond (outside of Edinburgh), to the eastern end of the wall. The second starting from Carlisle, ran to Birrens, a Roman fort near Ecclefechan, and thence, by a line not yet explored and indeed not at all certain, to Carstairs and the west end of the wall. A fort at Lyne near Peebles sug gests the existence of an intermediate link between them. There is nothing to indicate that the erection of the wall of Pius meant the abandonment of the wall of Hadrian. Rather, both barriers were held together, and the district between them was regarded as a military area, outside the range of civilization. The advance, however, entailed a heavy demand on the man-power available, and it is not surprising to find that just at this time many of the forts in Wales were dismantled, that part of the island being now completely subdued.

The work of Pius brought no long peace. Sixteen years later disorder broke out in north Britain, apparently in the district between the Cheviots and the Derbyshire hills, and was repressed with difficulty after four or five years' fighting. Eighteen or 20 years later still (18o-185) another war broke out with a dif ferent issue. The Romans were driven south of Cheviot, and perhaps even farther. The government of Commodus, feeble in itself and vexed by many troubles, could not repair the loss, and the civil wars which soon raged in Europe (193-197) gave the Caledonians further chance. It was not till 208 that Septimius Severus could turn his attention to the island. He came thither in person, conducted a punitive expedition into Caledonia, set himself to consolidate the position once more, and then, in the fourth year of his operations, died at York. Amid much that is uncertain and even legendary about his work in Britain, this is plain, that he fixed on the line of Hadrian's wall as his sub stantive frontier. His successors, Caracalla and Severus Alex ander (211-235), accepted the position, and many inscriptions refer to building or rebuilding executed by them for the greater efficiency of the frontier defences. The conquest of Britain was at last over. The wall of Hadrian remained for nearly 200 years more the northern limit of Roman power in the extreme west.

II. The Province of Britain and its Military System.— Geographically, Britain consists of two parts: (1) the com paratively flat lowlands of the south, east and midlands, suitable for agriculture and open to easy intercourse with the continent, i.e., with the rest of the Roman empire; (2) the district consist ing of the hills of Devon and Cornwall, of Wales and of northern England, regions lying more, and often very much more, than Goof t. above the sea, scarred with gorges and deep valleys, moun tainous in character, difficult for armies to traverse, ill fitted for peaceful pursuits. These two parts of the province differ also in their history. The lowlands, as we have seen, were con quered easily and quickly. The uplands were hardly subdued completely till the end of the 2nd century. They differ, thirdly, in the character of their Roman occupation. The lowlands were the scene of civil life. Towns, villages and country houses were their prominent features; troops were hardly seen in them save in some fortresses on the edge of the hills and in a chain of forts built in the 4th century to defend the south and south east coast, the so-called Saxon shore. The uplands of Wales and the north presented another spectacle. Here civil life was almost wholly absent. No country town or country house has been found more than 2om. north of York or west of Monmouthshire. The hills were one extensive military frontier, covered with forts and strategic roads connecting them, and devoid of town life, country houses, farms or peaceful civilized industry. This geo graphical division was not reproduced by Rome in any adminis trative partition of the province. At first the whole was gov erned by one legatus Augusti of consular standing. Septimius Severus made it two provinces, superior and inferior, the former of which included Caerleon and Chester, the latter Lincoln, York, and apparently Hadrian's wall, but we do not know how long this arrangement lasted. In the 4th century there were five provinces, Britannia Prima and Secunda, Flavia and Maxima Caesariensis and (for a while) Valentia, ruled by praesides and consulares under a vicarius, but the only thing known of them is that Britannia Prima included Cirencester.

The army which guarded or coerced the province consisted, from the time of Hadrian onwards, of (r) three legions, the Second at Isca Silurum (Caerleon-on-Usk, q.v.), the Sixth at Eburacum (q.v.; now York), the Twentieth at Deva (q.v.; now Chester), a total of some ; 5,000 heavy infantry; and (2) a large but uncertain number of auxiliaries, troops of the second grade, organized in infantry cohorts or cavalry aloe, each Soo or 1,000 strong, and posted in castella nearer the frontiers than the legions. The legionary fortresses were large rectangular enclosures of 5o or 6o acres, surrounded by strong walls of which traces can still be seen in the lower courses of the north and east town-walls of Chester, in the abbey gardens and elsewhere at York, and on the south side of Caerleon. The auxiliary castella were like wise square or oblong in shape but were hardly a tenth of the size, varying generally from three to six acres according to the size of the regiment and the need for stabling. Of these about r oo are known. The internal arrangements follow one general plan, but in some cases the buildings within the walls are all of stone, while in others, principally (it seems) forts built before 150, wood is used freely and only the few principal buildings seem to have been constructed throughout of stone. Chief among these latter, and in the centre of the whole fort, was the head quarters, in Lat. Principia or Praetoriutn. This was a rectangular structure with only one entrance which gave access, first, to a small cloistered court, then to a second open court, and finally to a row of three, five, or even seven rooms containing the shrine for official worship, the treasury and other offices. Close by were officers' quarters, generally built round a tiny cloistered court, and substantially constructed storehouses with buttresses and dry basements. These filled the middle third of the fort. At the two ends were barracks for the soldiers. No space was allotted to private religion or domestic life. The shrines which voluntary worshippers might visit, the public bath-house (as a rule), and the cottages of the soldiers' wives, camp followers, etc., lay outside the walls. Such were nearly all the Roman forts in Britain. They differ somewhat from Roman forts in Germany or other provinces, though most of the differences arise from the different usage of wood and of stone in various places.

Forts of this kind were dotted all along the military roads of the Welsh and northern hill-districts. In Wales a road ran from Chester past a fort at Caer-hun (near Conway) to a fort at Carnarvon (Segontium). A similar road ran along the south coast from Caerleon-on-Usk past a fort at Cardiff and perhaps others to Carmarthen and beyond. A third, roughly parallel to the shore of Cardigan bay, with forts at Llanio, Pennal, Tomen y-mur (near Festiniog), and Caer Llugwy, connected the north ern and southern roads, while the interior was held by a system of roads and forts not yet fully understood but discernible at such points as Caer-gai on Bala lake, Caersws, Castell Cohen near Llandrindod Wells, the Gaer near Brecon, Merthyr and Gelly gaer. In the north of Britain we find three principal roads. One led due north from York past forts at Catterick bridge, Pierce bridge, Binchester, Lanchester, Ebchester to the wall and to Scot land, while branches through Chester-le-Street reached the Tyne bridge (Pons Aelius) at Newcastle and the Tyne mouth at South Shields. A second road, turning north-west from Catterick bridge, mounted the Pennine chain by way of forts at Rokeby, Bowes and Brough-under-Stainmoor, descended into the Eden valley, where it joined the third route, reaching Hadrian's wall near Carlisle (Luguvallium) by way of Old Penrith (Voreda), and running on to Birrens. The third route, starting from Chester and passing up the western coast, is more complex, and exists in duplicate, the result perhaps of two different schemes of road making. Forts in plenty can be detected along it, notably Man chester (Mancunium or Mamucium), Ribchester (Bremeten nacum), Brougham castle (Brocavum), and on a western branch, ' Watercrook near Kendal, Waterhead near the hotel of that name on Ambleside, Hardknott above Eskdale, Ravenglass (probably Clanoventa), Maryport (Uxellodunum), and Old Carlisle (possibly Petrianae). In addition, two or three cross roads, not yet suf ficiently explored, maintained communication between the troops in Yorkshire and those in Cheshire and Lancashire. This road system bears plain marks of having been made at different times, and with different objectives, but we have no evidence that any one part was abandoned when any other was built. In general, however, it is clear that at no period were all the Roman forts in Britain simultaneously occupied. Garrisons were moved else where as the country round them grew quieter. Thus, Gellygaer in South Wales and Hardknott in Cumberland have yielded nothing later than the opening of the 2nd century. On the other hand, forts which had been abandoned might be restored if cir cumstances changed. Thus, in Wales some of those which had been dismantled under Pius, were rebuilt by Severus, notably Segontium.

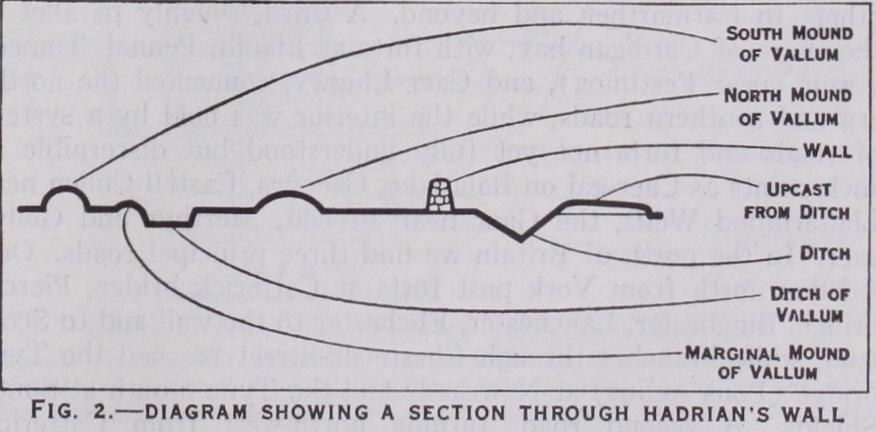

Besides these detached forts and their connecting roads, the north of Britain was defended by Hadrian's wall (figs. 1 and 2). The history of this wall has been given above. The actual works are threefold. First, there is that which to-day forms the most striking feature of the whole, the wall of stone 6-8ft. thick, and originally perhaps 14f t. high or a little higher, with a deep ditch in front, and forts (17 at very irregular intervals) and "mile castles" and turrets (both much more regularly spaced) and a connecting road behind it. On the high moors between Chollerford and Gilsland its traces are still plain, as it climbs from hill to hill and winds along perilous precipices. Secondly, there is, to the south of the wall, the so-called "Valium," in reality no vallum at all, but a broad flat-bottomed ditch out of which the earth has been cast up on either side into regular and continuous mounds that resemble ramparts. Thirdly, to the west of Birdoswald fort there were discovered in 1895 the remains of a previously unknown wall, constructed of sods laid in regular courses, with a ditch in front. This turf wall can be traced for r gym., running roughly parallel to the stone wall, with the line of which its ends ultimately coincide. It is certainly older than the other and, as our ancient writers mention two wall-builders, Hadrian and Septimius Severus, it was at first inferred that Hadrian built his wall of turf and Severus reconstructed it in stone. Recent excavation has shown this attractive theory to be untenable by proving, first, that even in the section where both walls appear, the mile castles and turrets on the stone wall are of Hadrianic date and, second, that the ditch of the turf wall was deliberately filled up after it had been open for only a brief period.

The meaning of the vallum has been much discussed. John Hodgson and Bruce, the local authorities of the loth century, supposed that it was erected to defend the wall from southern insurgents. Others have ascribed it to Agricola, or have thought it to be the wall of Hadrian, or even assigned it to pre-Roman natives. It is now clear that it is a Roman work, no older than Hadrian, and that it was not intended, like the wall, for military defence, but merely as a line of civil or legal delimitation. It is undoubtedly not earlier than certain of the forts, since it swings to the south to avoid them, and at some time in its history it was branched by having a series of causeways laid across it, at intervals which seldom exceed 4o or so yards. Certain of the forts, on the other hand, are undoubtedly earlier than the stone wall, since this is built either wholly or partially over the north ends of their east and west ditches. Further, in at least two instances (Birdoswald and Chesters) the fort was practically doubled in size before the stone wall was erected. These data have suggested to the excavators the following provisional hy pothesis as to the sequence of events, all of them compressed into a space of about seven years—(a) establishment of a line of small forts, with or without the vallum; (b) enlargement of some of the forts, and construction of the vallum, if not already in existence; (c) breaching of the vallum, and building of the stone wall as a link between the forts. The hypothesis accounts for many of the phenomena, but leaves others unexplained, notably (r) the turf wall and (2) a stone foundation rift. wide discovered in 1925, running for a mile west of the fort of Aesica (Great Chesters) immediately in front of the stone wall, beneath which it finally disappears. Much spade-work remains to be done before a completely satisfactory solution is in sight.

III. The Civilization of Roman Britain.

Behind these Iii. The Civilization of Roman Britain.—Behind these formidable garrisons, sheltered from barbarians and in easy con tact with the Roman empire, stretched the lowlands of southern and eastern Britain. Here a civilized life grew up, and Roman culture spread. This part of Britain became Romanized. In the lands looking on to the Thames estuary (Kent, Essex, Middlesex) the process had perhaps begun before the Roman conquest. It was continued after that event, and in two ways. To some extent it was definitely encouraged by the Roman government, which here, as elsewhere, founded towns peopled with Roman citizens —generally discharged legionaries—and endowed them with fran chise and constitution like those of the Italian municipalities. It developed still more by its own automatic growth. The coherent civilization of the Romans was accepted by the Britons, as it was by the Gauls, with something like enthusiasm. Encouraged per haps by sympathetic Romans, spurred on still more by their own instincts, and led no doubt by their nobles, they began to speak Latin, to use the material resources of Roman civilized life, and in time to consider themselves not the unwilling sub jects of a foreign empire, but the British members of the Roman state. The steps by which these results were reached can to some extent be dated. Within a few years of the Claudian invasion a colonia, or municipality of time-expired soldiers, had been planted in the old native capital of Colchester (Camulodunum), and, though it served at first mainly as a fortress and thus provoked British hatred, it soon came to exercise a civilizing influence. At the same time the British town of Verulamium (St. Albans) was thought sufficiently Romanized to deserve the municipal status of a municipium, which at this period differed little from that of a colonia. London became important. Romanized Britons must now have begun to be numerous. In the great revolt of Boadicea (6r) the nationalist party seem to have massacred many thousands of them along with actual Romans. Fifteen or 20 years later, the movement increases. Towns spring up, such as Silchester, laid out in Roman fashion, furnished with public buildings of Roman type, and filled with houses which are Roman in fittings if not in plan. The baths of Bath (Aquae Sulis) are exploited. Another colonia is planted at Lincoln (Lindum), and a third at Gloucester (Glevum) in g6. A new "chief judge" is appointed for increasing civil business. The tax-gatherer and recruiting officer begin to make their way into the hills. During the 2nd century progress was perhaps slower, hindered doubtless by the repeated risings in the north. It was not till the 3rd century that country houses and farms became common in most parts of the civilized area. In the beginning of the 4th century the skilled artisans and builders, and the cloth and corn of Britain were equally famous on the continent. This probably was the age when the prosperity and Romanization of the province reached its height. By this time the town populations and the educated among the country-folk spoke Latin, and Britain regarded itself as a Roman land, in habited by Romans and distinct from outer barbarism.The civilization which had thus spread over half the island was genuinely Roman, identical in kind with that of the other western provinces of the empire, and in particular with that of northern Gaul. But it was defective in quantity. The elements which corn pose it are marked by smaller size, less wealth and less splen dour than the same elements elsewhere. It was also uneven in its distribution. Large tracts, in particular Warwickshire and the adjoining midlands, were very thinly inhabited. Even densely peopled areas like north Kent, the Sussex coast, west Gloucester shire and east Somerset, immediately adjoin areas like the Weald of Kent and Sussex where Romano-British remains hardly occur.

The administration of the civilized part of the province, while subject to the governor of all Britain, was practically entrusted to local authorities. Each Roman municipality ruled itself and a territory, perhaps as large as a small county, which belonged to it. Some districts formed part of the Imperial domains, and were administered by agents of the emperor. The rest, by far the larger portion of the country, was divided up among the old native tribes or cantons, some ten or 12 in number, each grouped round some country town where its council (ordo) met for can tonal business. This cantonal system closely resembles that which we find in Gaul. It is an old native element recast in Roman form, and well illustrates the Roman principle of local govern ment by devolution.

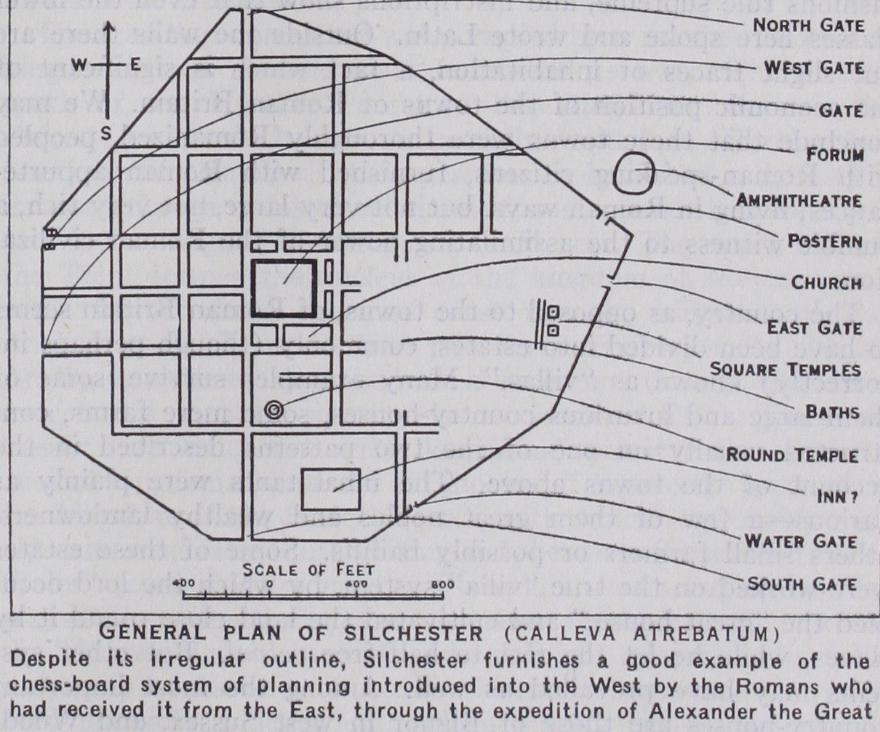

In the general framework of Romano-British life the two chief features were the town, and the villa. Apart from Lugu vallium (Carlisle) and Corstopitum (Corbridge upon Tyne), which lay within the military area and were really of the nature of "bazaars" (as it were) for the soldiers of the frontier garrison, the towns of the province, as we have already implied, fall into two classes. Five modern cities, Colchester, Lincoln, York, Gloucester and St. Albans, stand on the sites, and in some f rag mentary fashion bear the names of five Roman municipalities founded by the Roman government with special charters and con stitutions. All of these reached a considerable measure of pros perity. None of them rivals the greater municipalities of other provinces. Besides them we trace a larger number of country towns, varying much in size, but all possessing in some degree the characteristics of a town. The chief of these seem to be cantonal capitals, probably developed out of the market centres or capitals of the Celtic tribes before the Roman conquest. Such are Isurium Brigantum (Aldborough), capital of the Brigantes, i 2m. north west of York and the most northerly Romano-British town; Ratae, now Leicester, capital of the Coritani; Viroconium, now Wroxeter, near Shrewsbury, capital of the Cornovii ; Venta Si lurum, now Caerwent, near Chepstow; Corinium, now Cirencester, capital of the Dobuni; Isca Dumnoniorum, now Exeter, the most westerly of these towns ; Durnovaria, now Dorchester, in Dorset, capital of the Durotriges; Venta Belgarum, now Winchester; Calleva Atrebatum, now Silchester, rom. south of Reading; Duro vernum Cantiacorum, now Canterbury; and Venta Icenorum, now Caister-by-Norwich. Besides these country towns, Lon dinium (London) was a rich and important trading town, as the remarkable objects discovered in it abundantly prove, centre of the road system, and the seat of the finance officials of the prov ince, while Aquae Sulis (Bath) was a spa provided with splendid baths, and a richly adorned temple of the native patron deity, Sul or Sulis, whom the Romans called Minerva. Many smaller places, too, for example, Magnae or Kenchester near Hereford, Durobri vae or Rochester in Kent, another Durobrivae near Peterborough, a site of uncertain name near Cambridge, another of uncertain name near Chesterford, exhibited some measure of town life. London, one of the larger cities of the western empire, may well have had a character of its own, but direct evidence as to this is unfortunately lacking. Of the other towns we can form a good general idea through the excavations that have been carried out at Silchester, Caerwent and Wroxeter. Public life centred round the forum and the adjoining basilica. Here the local authorities had their offices, justice was administered, traders trafficked, citi zens and idlers gathered. In fig. 3, though we cannot apportion the rooms to their precise uses, the great hall was plainly the basilica, for meetings and business; the rooms behind it were perhaps law courts, and some of the rooms on the other three sides of the quadrangle may have been shops. The temples might be either square or round, and at Silchester there was a small Christian church of the so-called "basilican" type, of which many examples have been found in other countries, especially in Roman Africa. A suite of public baths was always a prominent feature, and outside the walls there was usually an amphitheatre. The private houses were of two types. They consisted either of a row of rooms, with a corridor along them, and perhaps one or two additional rooms at one or both ends, or of three such corri dors and rows of rooms, forming three sides of a large square open yard. They were detached houses, standing each in its own garden, and not forming terraces or rows. They differ widely from the town houses of Rome and Pompeii; they are less unlike some of the country houses of Italy and Roman Africa, but their real parallels occur in Gaul, and they may be Celtic types modi fied to Roman use—like Indian bungalows. Their internal fit tings—hypocausts, frescoes, mosaics—are everywhere Roman. The largest Silchester house, with a special annex for baths, is usually taken to be a guest-house or inn for travellers between London and the west.

The streets vary in width. The intersect regularly at right angles, dividing the town into square blocks, like modern Mann heim or Turin, according to a Roman system usual in both Italy and the provinces, and derived ultimately from Babylon and :.he East through Alexander the Great and his successors. The walls are often later than the streets, having been erected when the peace of the province began to be seriously threatened by barbarian inroads. The inference suggested by the appearance of the chess board system of town-planning is confirmed by the testimony of the numberless small objects recovered in the course of the ex cavations—coins, pottery, window and bottle and cup glass, bronze ornaments, iron tools, etc. Few of these are individually notable. Traces of late Celtic art are singularly absent ; Roman fashions rule supreme, and inscriptions show that even the lower classes here spoke and wrote Latin. Outside the walls there are but slight traces of inhabitation, a fact which is significant of the economic position of the towns of Roman Britain. We may conclude that these towns were thoroughly Romanized, peopled with Roman-speaking citizens, furnished with Roman appurte nances, living in Roman ways, but not very large, not very rich, a humble witness to the assimilating power of the Roman civiliza tion.

The country, as opposed to the towns, of Roman Britain seems to have been divided into estates, commonly (though perhaps in correctly) known as "villas." Many examples survive, some of them large and luxurious country-houses, some mere farms, con structed usually on one of the two patterns described in the account of the towns above. The inhabitants were plainly as various—a few of them great nobles and wealthy landowners, others small farmers or possibly bailiffs. Some of these estates were worked on the true "villa" system, by which the lord occu pied the "great house," and cultivated the land close round it by slaves, while he let the rest to half-free coloni. But other sys tems may have prevailed as well. Among the most important country-houses are those of Bignor in west Sussex, and Wood chester and Chedworth in Gloucestershire. At the other extreme were the villages, whose remains can be detected in the Thames valley and elsewhere, and which housed the humbler members of the population.

The wealth of the country was principally agrarian, and the needs of the army of occupation must have helped to stimulate production. Wheat and wool were exported in the 4th century, when, as we have said, Britain was especially prosperous. But the details of the trade are unrecorded. More is known of the lead and iron mines which, at least in the first two centuries, were worked in many districts—lead (from which silver was ex tracted) in Somerset, Shropshire, Flintshire and Derbyshire; iron in the west Sussex Weald, the Forest of Dean, and (to a slight extent) elsewhere. Other minerals were less notable. The gold mentioned by Tacitus proved scanty, although there seem to be clear indications of Roman gold-mining in Wales. The Cornish tin, according to present evidence, was worked comparatively little, and perhaps most in the later Empire.

Lastly, the roads. Here we must put aside all idea of "four great roads." That category is probably the invention of anti quaries, and certainly unconnected with Roman Britain (see ERMINE STREET). Instead, we may distinguish four main groups of roads radiating from London, and a fifth which runs obliquely. One road ran south-east to Canterbury and the Kentish ports, of which Richborough (Rutupiae) was the most frequented. A second ran west to Silchester, and thence by various branches to Winchester, Exeter, Bath, Gloucester and South Wales. A third, known afterwards to the English as Watling street, ran by St. Albans wall and near Lichfield (Lectocetum) to Wroxeter and Chester. It also gave access by a branch to Leicester and Lincoln. A fourth served Colchester, the eastern counties, Lincoln and York. The fifth is that known to the English as the Fosse, which joins Lincoln and Leicester with Cirencester, Bath and Exeter. Besides these five groups, an obscure road, called by the Saxons Akeman Street, gave alternative access from London through Alchester (outside of Bicester) to Bath, while another obscure road winds south from near Sheffield, past Derby and Birmingham, and con nects the lower Severn with the Humber. By these roads and their various branches the Romans provided adequate communi cations throughout the lowlands of Britain.

IV. The End of Roman Britain.

About 286 Carausius, admiral of the "Classis Britannica," quarrelled with the central government and proclaimed himself emperor. He remained in control of the island until 293, when he was murdered by one of his own officers, Allectus, who essayed to succeed him. By this time, however, the authorities at Rome had resolved on recon quest. An expedition under the personal command of the future emperor, Constantius Chlorus, successfully evaded the wait ing ships of Allectus, and the usurper was slain in a land-battle. Extensive changes in the distribution of the garrison seem to have followed. Danger threatened, not only from the Picts beyond Hadrian's wall, but also from the sea. It may have been now that Caerleon was evacuated and the Second Legion sent elsewhere. At all events a special coast defence, reaching from the Wash to Spithead, was established against Saxon pirates: there were forts at Brancaster, Burgh Castle (near Yarmouth), Walton (near Felixstowe), Bradwell (at the mouth of the Colne and Black water), Reculver, Richborough, Dover and Lympne (all in Kent), Pevensey in Sussex, and Porchester near Portsmouth. The Irish (Scoti), too, were becoming increasingly aggressive. It is, there fore, not surprising that a new fort should have been erected at Cardiff and perhaps one on the Isle of Wight. For a time these measures were effective and the province prospered. But after about 35o the barbarian assaults became more frequent and more terrible. The building of a series of stone watch-towers along the Yorkshire coast, from the Tees to Flamborough head, is very significant.At the end of the century Magnus Maximus, claiming to be emperor, withdrew many troops from Britain and a later pre tender did the same. Early in the 5th century the Teutonic con quest of Gaul cut the island off from Rome. This does not mean that there was any great "departure of the Romans." The central government simply ceased to send the usual governors and high officers. The Romano-British were left to themselves. Their position was weak. Their fortresses lay in the north and west, while the Saxons attacked the east and south. Their trained troops, and even their own numbers, must have been few. It is intelligible that they followed a precedent set by Rome in that age, and hired Saxons to repel Saxons. But they could not com mand the fidelity of their mercenaries, and the Saxon peril only grew greater. It would seem as if the Romano-Britons were speedily driven from the east of the island, and as if the Saxons, though apparently unable to gain a hold on the western uplands, were able to prevent the natives from recovering the lowlands. Thus driven from the centres of Romanized life, from the region of walled cities and civilized houses, into the hills of Wales and the north-west, the provincials underwent an intelligible change. The Celtic element, never quite extinct in those hills and, like most forms of barbarism, reasserting itself in this wild age—not without reinforcement from Ireland—challenged the remnants of Roman civilization and in the end absorbed them. The Celtic language reappeared ; the Celtic art emerged from its shelters in the west to develop in new and mediaeval fashions.