Shan States

SHAN STATES.) For Burmese law see INDIAN LAW.

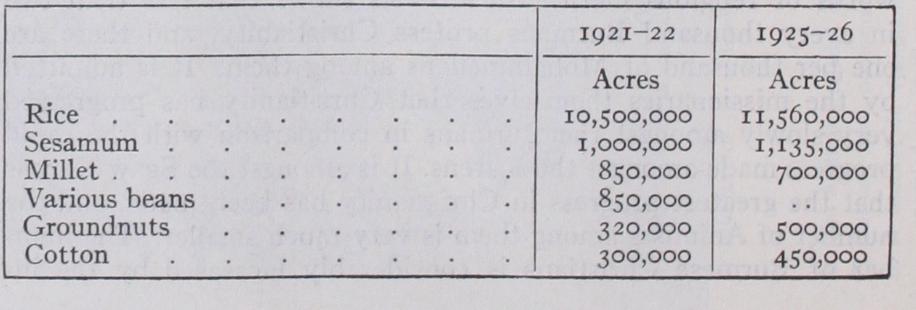

Agriculture and Industries.—Burma is essentially an agri cultural country. Only 15% of the people were classed as urban in 1921, and a considerable proportion of this number were natives of India. The agriculture is concentrated on the alluvial lands of the delta and the valleys of the Irrawaddy, Chindwin and Sittang. Rice is by far the most important crop, and occupies two-thirds of the cropped area. The production of rice is roughly 7,000,000 tons per year, or more than half a ton per head of population. There is, in consequence, a large export. Where the rainfall is less than 4oin. rice cannot be grown without irrigation, and culti vation in the dry zone is largely concentrated on sesamum, millet, groundnuts, cotton and beans. In the dry belt nearly one and a half million acres are irrigated. At the time of the British annexa tion of Burma there were some old irrigation systems in the Kyaukse and Minbu districts, which had been allowed to fall into disrepair, and these have now been renewed and extended. In addition to this the Mandalay canal, 4om. in length, with 14 dis tributaries, was opened in 1902; the Shwebo canal, 27m. long, was opened in 1906, and later, two branches 29 and tom. in length, and the Mon canal, started in 1904, 53m. in length. Throughout the country, fruits, vegetables and tobacco are grown for home consumption, and fodder where required. In comparison with India, there is room for considerable agricultural expansion in Burma, and official returns class 5o million acres as cultivable waste, as against under 20 million acres of "occupied" land. Out of about 16 million acres under cultivation (not including the Shan States) the areas occupied by the principal crops are :— There are numerous rubber plantations, especially in Mergui and Tavoy.

Small humped oxen are kept everywhere as beasts of burden and for use in ploughing. They are replaced to a considerable extent in the delta and wetter areas by the heavier water buffalo. Herds of small goats are numerous in the dry belt, and small numbers of very poor sheep are reared.

Fisheries and fish-curing exist both along the sea-coast of Burma and in inland tracts, and afforded employment to persons in 1921. Salted fish forms, along with boiled rice, one of the chief articles of food among the Burmese. Some pearling grounds in the Mergui archipelago are worked spasmodically for mother-of pearl.

The most important mineral product of Burma is petroleum. The following table shows the production in recent years: 1909-13 average . . . . . . 236,500,000 gals.

1916-20 average . . . . . 282,600,000 gals.

1921-25 average . . . . . . . 276,500,000 gals. (249 gals.=one metric ton) Since 1918 the value of the output has been nearly Rs. i o crores. Very little use has yet been made of the extensive deposits of brown coal or lignite. The most important fields lie in the Chin dwin valley and in old lake basins of the Shan plateau. Some of the latter also yield oil shale. Mention has been made of the silver lead deposits of Bawdwin; in 1925 the output of silver and lead ore, mainly from these mines, was 322,000 tons, valued at 108 lakhs. The Burma Corporation produced 48,00o tons of refined lead ; 4,83 2,0000z. of refined silver, as well as zinc and copper. The mines of Tenasserim produced large quantities of tin and tungsten during the years 1914-18, but the present output fluctu ates widely with the price of the metals. The output of tin in 1925-26 was 2,220 tons, worth 35 lakhs. The historic Burma Ruby Mines, Ltd., after many vicissitudes, went into liquidation in 1925-26. The famous jade of China is found in the north of Burma and exported overland to China via Mogaung and Bhamo. The mines are situated beyond Kamaing, north of Mogaung, in the Myitkyina district. The miners are all Kachins, and the right to collect the jade duty of 334% is farmed out by the Government to a lessee, who has hitherto always been a Chinaman. The amount obtained has varied considerably. In 1887-88 the rent was Rs.5o, 000. This dwindled to Rs.36,o0o in 1892-93, but the system was then adopted of letting for a term of three years and a higher rent was obtained. The value varies enormously according to colour, which should be a particular shade of dark green. Semi-trans parency, brilliancy and hardness are, however, also essentials. The old river mines produced the best quality. The quarry mines on the top of the hill near Tawmaw produce enormous quantities, but the quality is not good.

Gold is found in most of the rivers in Upper Burma, but the gold-washing industry is for the most part spasmodic, in the intervals of agriculture. Amber is extracted by Kachins in the Hukawng valley, but the quality of the fossil resin is not very good. Salt is manufactured at various places in Upper Burma, notably in the lower Chindwin, Sagaing, Shwebo, Myingyan and Yamethin districts, as well as in the Shan States. Iron is found in many parts of the hills.

Communications.—From time immemorial the principal highway of Burma has been the Irrawaddy (q.v.) and its tribu taries. Even at the present day the railways have rather supple mented than replaced the rivers as highways of trade. The Burma railways (1,749m. in 1925) are for the most part the property of the province, but are operated by the Burma Rail ways, Ltd. They are all metre gauge. The main line runs from Rangoon to Mandalay, where it is interrupted by the Irrawaddy, but is continued on the opposite bank of the river to Myitkyina. There is no railway connection with India proper, nor with any neighbouring country. The centre of the oilfields, Yenangyaung, is still only accessible by river. Burma is badly in need of roads, which are non-existent over most of the country. There is not even a motor road from Rangoon to Mandalay. Outside Rangoon and Mandalay, there are no hotels ; but there are houses, built primarily for the use of Government officials on tour, where the traveller may obtain shelter for a nominal payment. Most of the smaller villages of Burma consist of a collection of from a dozen to '00 or more huts, built of timber uprights and bamboo. The villages are surrounded by a bamboo or wooded stockade—mainly as a protection against wild animals. Whilst the civil head of the village is the thugyi, or headman, chosen by the villagers and recognized by Government, the spiritual head of the village is the senior hpoongyi of the neighbouring hpoongyi kyaung. Larger villages or towns arise as collecting or distributing centres, or have important bazaars. In many cases their importance has been enhanced by their having been made the administrative headquarters of a district or a division. A large number of the more important towns are river ports.

The staple industry of Burma is agriculture, but many culti vators are also artisans in the by-season. In addition to rice growing, the felling of timber, and the fisheries, the chief occu pations are rice-husking, silk-weaving and dyeing. The most im portant of the non-agricultural manufacturing industries is that connected with the working and refining of oil. The principal refineries are at Syriam, near Rangoon. The introduction of cheap cottons and silk fabrics has dealt a blow to hand-weaving, while aniline dyes are driving out the native vegetable product; but both industries still linger in the rural tracts. The best silk weavers are to be found at Amarapura. The total number of per sons engaged in the production of textile fabrics in Burma, according to the census of 1921, was 115,338, against 419,007 in 1901. The chief dye-product of Burma is cutch, a yellow dye obtained from the wood of the sha tree. Cutch-boiling forms the chief means of livelihood of a number of the poorer classes in the Prome and Thayetmyo districts of Lower Burma, and a subsidiary means of subsistence elsewhere. Cheroot making and smoking is universal with both sexes. The chief arts of Burma are lacquer working (centred at Pagan), wood carving and silver work. The floral wood-carving is remarkable for its freedom and spontane ity. The carving is done in teak wood when it is meant for fixtures, but teak has a coarse grain, and otherwise yamane clog wood, said to be a species of Gmelina, is preferred. The tools employed are chisel, gouge and mallet. The design is traced on the wood with charcoal, gouged out in the rough, and finished with sharp fine tools, using the mallet for every stroke. The great bulk of the silver work is in the form of bowls of different sizes, in shape something like the lower half of a barrel, only more con vex, of betel boxes, cups and small boxes for lime. Both in the wood-carving and silver work the Burmese character displays itself, giving boldness, breadth and freedom of design, but a general want of careful finish.

The following table shows the progressive value of the trade of Burma since 1871-72 in lakhs of rupees (one lakh = Rs. i oo,000) .

Year Imports Exports 1871-72 . . . . . . . . 3.16 3.78 1881-82 . . . . . . . 6.38 8•o6 1891-92 . . . . . . . . 1.050 1•267 1901-02 . . . . . . . . I .2 78 1•874 1909-14 . . . . . . . . 2.405 3.723 1914-19 . . . . . . . . 2.285 3.838 1919-24 . . . . . . . . 3.882 6.136 1925-26 . . . . . . . . 4.588 7.773 Approximately 86% of the foreign trade of Burma passes through Rangoon (q.v.). Other leading ports are Bassein, a rice port on the west of the delta ; Akyab, the outlet of Arakan ; and Moul mein, Tavoy and Mergui, which serve the Tenasserim division. Of the export trade, well over one-third is with India, more than one-third with other parts of the British empire, especially the home country and only one-quarter with foreign countries. Of the import trade nearly one-half is with India and only one-fifth with foreign countries outside the British empire. The principal exports are rice, petroleum products, timber, cotton, hides and skins, metals and ores, beans, rubber and lac. The export of rice varies between two and three million tons, and in 1925-26 repre sented 44% of the total exports. The principal imports are cotton goods, machinery and hardware, coal, silk and sugar. The currency in Burma is that in use throughout India, but the common unit of weight is the Burmese viss.

The earliest history of Burma is mainly conjectural. It is believed that the aborigines were a Negrito race of which the only survivals are to be found in the Andaman islands, once part of the mainland. The present inhabitants of Burma are descendants of different Mongolian tribes, which migrated at a remote period from western China and Tibet, by the Irrawaddy and Salween rivers and penetrating into Arakan. The Tais or Shans spread over the Shan States and Siam, on both sides of the Chinese frontier, and encroached into Burma proper. The Krans went off into Arakan, the Pyus established a kingdom at Prome, and the Mons or Talaings in Pegu. Immigrants came from Chittagong, into Arakan, from Manipur into Upper Burma, and from Madras and Malaya into Pegu and Tenasserim. The Hindu mythology ousted Mongolian traditions, but Buddhism, subdued by Brahminism in India, in its turn overcame Brahmin ism in Burma, and through its wonderful monastic system has directed the religious lives of the people for some 2,000 years. Legend and fable, in which innumerable tribal chiefs figured as mighty kings, only gave way to authenticable history when King Anawrahta (a contemporary of William the Conqueror) founded the Pagan dynasty in A.D. 10J4. He and his ten suc cessors were the first real rulers of Burma. He expelled the debased Ari priesthood and forcibly imported the purest form of Buddhism, monks and scriptures from its seat at Thaton. The Ananda, the gem of the Pagan pagodas, was built in the reign of Kyanzittha (1084-1112). The Pagan dynasty included pious sovereigns like Htilominlo (1210-34), and his son, Kyaswa 50), but the later sovereigns degenerated, and the last of them —Narathihapate—earned the vengeance of Kublai Khan and lost his kingdom in 1287 by the execution of three distinguished ambassadors with their retinues sent by the emperor of China.

The Shan Dominion (1287-1531).

Under the Shan irrup tion chaos supervened, and for two and a half centuries Burman history is a confused record of princes and upstarts, Talaings, Shans and Burmans constantly contending for the mastery, petty kingdoms rising and falling at Ava, in Pegu, at Toungoo, and in Arakan. Among the more famous of the Pegu kings was Razadarit (1385-1423), a man of blood and treachery. A daughter of his, Shinsawbu and Dammazedi, a monk who turned layman and married her daughter, ushered in a period of com parative peace, recorded as the Golden Age of Pegu. It was during this epoch that the famous Shwedagon Pagoda of Dagon (Rangoon) was twice heightened and enriched, but still barbarous practices continued. The dynasty was overthrown by the house of Toungoo in 1531, which re-established a Burmese kingdom.

The Toungoo Dynasty.

Toungoo began as a stronghold for Burmese refugees against Shans and Talaings alike in 1280, and was ruled by 28 chiefs in all, of whom 15 perished by assassina tion. The last of the house, Tabinshwehti (1531--5o), with the aid of his brother-in-law, the famous general, Bayinnaung, cap tured Prome and Martaban, invaded Arakan, captured Pegu, attacked Siam, and was finally crowned at Ava, the Shan chiefs being ousted from Upper Burma. Bayinnaung (1551-81), who succeeded, had first to fight for his kingdom, then carry on a career of conquest. He captured the old Siamese capital of Ayutthia, subdued the Shan States and half Siam, and reigned over the whole of Burma, except Arakan. He exchanged missions with Bengal and Colombo, from whom he obtained a daughter and a sacred Tooth, but his enormous conscriptions of men and constant warfare reduced his own province almost to desolation. His son, Nandabayin, who followed in his footsteps, completed the ruin. The Siamese invaded Burma, and the Arakanese raided and burnt Pegu. The king was deposed and murdered, and for 16 years the kingdom was again split into petty States, some of which, including Ava, were retained by sons of Bayinnaung. A grandson of that monarch, Anaukpetlun (1605-28) reconquered the de-populated south, sacked the port of Syriam, and impaled its Portuguese governor, de Brito. He restored the monarchy and set up his court at Pegu. He commanded both the terror and the admiration of his subjects. The successors of Anaukpetlun re tired to Ava, and the monarchy became increasingly effete, though Thalun (1629-48) was a patron of learning. For about a century a series of weaklings nominally reigned at Ava. During this period Upper Burma was twice over-run by the Ming and Manchu Chinese, and five times by the Manipuris. Ava's authority over Pegu constantly diminished until in 1740 the Talaings set up a king of their own, and in the course of ten years had over-run the country round Ava. Against this unnatural Talaing supremacy a leader was found in a headman of Shwebo, Alangpaya, who founded the last dynasty of Burmese kings.

The Alangpaya Dynasty.

Alangpaya (Alompra), beginning with the defeat of small bodies of troops sent to capture him was eventually able to establish himself as king. His energy was marvellous, for, though he reigned for eight years only (1752-6o), in that brief period he had reconquered the whole country, captured Syriam, seized and sacked Pegu, defeated the Manipuris, completely subjugated the Talaings, established himself in Ran goon, and invaded Siam. The Talaings who survived fled to Siam, and the Delta was once more depopulated. While investing the Siamese capital, Ayutthia, for the fifth time in its history, he was stricken with illness, and, retiring by forced marches, died on the way.

Early European contact with Burma.

In the century that ended with Alangpaya the earliest European contact with Burma was that of the Portuguese, many of whom settled in the country and married Burmese wives. The Portuguese adventurer, de Brito, was left as governor of Syriam by the invading Arakanese, and Portuguese half-breeds formed contingents in some of the con tending armies, these and Armenians being found in considerable numbers in the sea-ports. The British and Dutch East India Companies had branches in Burma under junior representatives from about 1627, but both of them withdrew some 5o years later. In 1709 the British re-established a factory at Syriam, which lasted till 1743, when the Talaings burnt it down, suspecting that the English were aiding the Burmese. The English factory was then moved to Negrais and it was there that the settlement and garrison were treacherously massacred in Alangpaya's reign in 1759, on the pretext that they had helped the Talaings. The company unsuccessfully sent Captain Alves as an envoy to demand redress.When Dupleix sent two ships to save Syriam, besieged by Alangpaya, all the French officers were executed. The guns and the crews of the ships were a valuable accession to Alangpaya's military strength, and these European gunners were given a place of honour in his armies. There were many instances in which ships were seized and their crews enslaved. But in all these years the European Governments concerned were much too occupied with other commitments to exact serious retribution for outrages against their subjects.

Alangpaya's Successors.

Alangpaya was succeeded by his eldest son, Naungdawagyi, who, of ter three years, was succeeded by his brother, Hsinbyushin (1763-76), who again made Ava the capital. He raided Manipur in person, carrying away thou sands of its population into captivity, attacked Siam and eventu ally captured Ayutthia. This campaign was followed by a Chinese invasion, which the Burmese armies took four years to repel. A Siamese rising resulted in the Burmese being driven across the frontier. On the death of Hsinbyushin his son, Singu, reigned for six years only and was then murdered. The throne was seized by Bodawpaya (1782-1819), a son of the great Alangpaya, who shifted his capital to Amarapura, and annexed Arakan. He carried off 20,000 Arakanese into captivity, with the famous Mahamuni Buddha, which is now the Arakan pagoda at Mandalay. This subjugation was a contributory cause to the first Burmese war. The tyranny exercised over the defeated Arakanese, who were constantly dragged off in numbers to forced labour or military expeditions, provoked acts of rebellion entailing ruthless repression. Insurgent leaders took refuge in Chittagong and planned acts of war against the Burmese, leading to demands for their surrender as rebels. The indignities with which British envoys and missions to the Burma court were treated, merely served to increase the arrogance of the Burmese ruler. Manipur and Assam were once more over-run, and their inhabitants de ported, enslaved or massacred. When Bodawpaya died, his dominion. except on the Siamese side, extended further than ever before. His grandson, Bagyidaw (1819-37) succeeded. The Brit ish Government in India were incredibly patient until in 1824, Burmese troops moved across over the Cachar frontier. In March, the viceroy notified a state of war and the first British transports arrived at Rangoon. This first Burmese war of 1824 was ter minated by the Peace of Yandabu, the cession of Arakan and Ten asserim, the abandonment of all claims upon Assam and Manipur, and the payment by instalments of a crore of rupees. The two ceded territories were administered by commissioners as appan ages of Bengal. The Yandabu Treaty provided for a resident at the court of Ava, but it was not till 1830 that Major Burney was sent there. Burney established some influence with the court, but was never properly received by the king. Bagyidaw became melancholy mad, and in 1837 was superseded by his brother, Tharawadi Although Tharawadi refrained from the usual mas sacre of kinsmen on his accession, in deference to Burney's exhor tations, Burney's successors were treated ignominiously, and in 1840 the mission was withdrawn. A rebellion of the Shan States, mercilessly repressed, and a final uprising by the Talaings in Pegu, gave Tharawadi an excuse to return to the old atrocities. Before long he became so mad and outrageous in his doings that in 1845 his eldest son, Pagan Min, put him under restraint, and on his death succeeded to the throne (1846-53 ). Pagan Min was avari cious and immoral. The governor of Rangoon, Maung Ok, was notorious for his extortions. British ships having suffered greatly a small squadron was sent to Rangoon to demand redress and the removal of the governor. Pagan was defiant, and sent new gover nors with armies of several thousand men to Rangoon, Bassein and Martaban. British ships were fired upon, and Lord Dalhousie sent a stern ultimatum, expiring on April 1, 1852. No reply arriv ing, the second Burmese war began. The Burmese resistance was feeble, and on Dec. 20, 1852, Lord Dalhousie proclaimed the an nexation of the Pegu province. In the meantime a revolution had taken place and Pagan had been deposed by his brother, Mindon Min (18J3-78). The First Commissioner of Pegu, Captain, after wards Sir Arthur Phayre, took a mission to Amarapura to negotiate a commercial treaty. He was received politely, but the treaty was not secured. In 1857 Mindon shifted his capital to Mandalay, and occupied himself with civil reforms, substituting salaries to officials for the periodical levies which were hitherto the custom. The sal aries were seldom paid. In 1862 the several British territories were constituted the Province of British Burma, Phayre being the first chief commissioner. He succeeded in negotiating a commercial treaty, but the royal monopolies in which Mindon specialized stood in the way and evasions became so notorious that Phayre's suc cessor, Colonel Fytche, negotiated a second treaty, but without much practical effect. Mindon had two minor rebellions of princes to suppress, but in the absence of foreign wars devoted himself to pious works. He also sent a mission to Rome, Paris and London ; treaties were concluded with Italy and France, the former being purely diplomatic, but the latter gave too many rights to France and Mindon refused to ratify it. Machinery was imported and a teak church was built for Dr. Marks (S.P.G. missionary). In com parison with his predecessors Mindon was a humane monarch, and when he died of dysentery in 1876 he was genuinely mourned by his subjects.Thebaw (1876-1885) :—The End of the Burmese Mon archy.—The last of the kings of Burma owed his selection to the ambition of the Alenandaw queen, a masterful and ferocious lady, whose daughter, the notorious Supyalat, he married. While Mindon was dying the rival princes had been treacherously arrested, and they were kept imprisoned for over two years. On Feb. 15, 1879, the usual massacre of princes began. Mandalay had by this time become an Alsatia for all sorts of foreign riffraff, strongly anti British in their ideas, who misled the court into thinking that the affair would blow over. For the time being action was not taken, but the cup was filling up, and in 1879, after various incidents of Burmese truculence against British subjects had occurred, the resident and his whole staff withdrew from Mandalay. Thebaw sent envoys to Thyatmyo in 1879, and another one to Simla in 1882, which he recalled. In the meantime Thebaw was intriguing with the French Consul, M. Haas, and contracts for a French Rail way to Mandalay, and a French flotilla on the Irrawaddy, were actually signed. Disturbances broke out in various parts of Upper Burma, and a fresh massacre of political prisoners under cover of a bogus jail outbreak added to the excitement. The Bombay-Burma Trading Corporation were arbitrarily fined Rs. 230,000 for alleged breaches of contract. It was not until Oct. 1885, that an ultimatum was sent, to which Thebaw gave an evasive and defiant reply, issu ing a Proclamation calling upon his subjects to unite and annihilate the English barbarians and conquer and annex their country. The British Expeditionary Force, under Sir Harry Prendergast, crossed the frontier on Nov. 4, proceeding up the Irrawaddy, and by the end of that month Thebaw and his family had been deported to India, and the kingdom of Burma had ceased to exist, annexation being proclaimed by Lord Dufferin on Jan. 1, 1886.

Burma Under British Rule.

Burma remained a chief corn missionership under Sir Charles Bernard, Sir Charles Crosthwaite, Sir Alexander Mackenzie, and Sir Frederick Fryer, the last becom ing the first lieutenant-governor, in 1$97. He was followed by Sir Hugh Barnes, Sir Herbert Thirkell-White, and Sir Harvey Adam son. In 1915, Sir Harcourt Butler succeeded for two years, when he was translated to the United Provinces. Sir Reginald Craddock was the last lieutenant-governor, and on the completion of his term of office in 1922, Sir Harcourt Butler returned as the first governor under the new Constitution.These successive changes in the status of the head of the province corresponded roughly with stages in the development of Burma. When Arakan and Tenasserim had been under British rule for 103 years, Pegu for 74, and Upper Burma for 42, Arakan and Tenasserim had been so reduced and depopulated that they gave but little trouble, Pegu took several years to pacify, and the pacification of Upper Burma was not completed until after five years, at first engaging the energies of 32,000 Regular troops. A force of military police 16,0o0 strong, half of which was recruited from India, was formed soon after the annexation, and the Chins on the north-west, and the Kachins on the north-east have occa sionally given trouble by risings, the last of which occurred during the Great War. Perhaps never in the history of any country has the contrast between its past and its present been so great and so rapid.

Financial stringency first retarded progress, and the administra tors of Burma long chafed against restrictions which Finance Ministers in India felt bound to impose. The civilizing influences of the impartial administration of justice, of communications by rail, river and road, of the wonderful development of trade, and the direct humanizing effects of education, medical relief, and the la bours of the great Christian missions, Catholic and Protestant, could not but produce a change in the outlook and life of the great majority of the Burmese people.

There have been boycotts of British goods, of the new Rangoon university and Government schools, echoes of Gandhi's Non-Co operation movement, and agitations against payment of taxes, but these movements, with firm administration, have all subsided, though a section of "Nationalists" is still pressing for immediate home rule.

The early years of the new Constitution of Burma have passed without any special crisis, and among the features of this period have been the governor's efforts to suppress slavery and human sacrifices in the unadministered tracts of the Mukong Valley and the ILachin "Triangle." Burma enjoys wider franchise than the Indian provinces, women having the necessary property qualifica tions being enfranchised. Its effort in the Great War was remark able, and four Battalions of Burmans were enrolled at that time, but the enthusiasm for soldiering dies away in peacetime, and the local battalions consist mainly of Karens, Chins and Kachins. The Burmese are a particularly cheerful and amusement-loving people, with pronounced artistic talents and love of beautiful things and bright colours. The reception accorded to the prince of Wales in 1922 was a most enthusiastic one, after an attempt, engineered from India, to boycott his visit had completely failed. The pagodas, her monasteries, and her emancipated womanhood appeal to Eu ropeans and make it difficult to believe that a country of such apparent sweetness and light can have so recently passed through a thousand years of oppression. For later history see INDIA. See Dautremer, Burma under British Rule (trans. 1913) ; Sir C. Crosthwaite, The Pacification of Burma (1913) ; Sir H. T. White, Burma (1923) .