The British Budget

THE BRITISH BUDGET Preparation.—It is a peculiar feature of British finance that no proposal which involves expenditure can be carried out without the approval of the Treasury. During the financial year depart ments approach the Treasury with requests to sanction additional expenditure, either forthwith or from some future date. The Treasury requires a reasoned statement to justify the proposals, and if it is not at first satisfied calls for further explanations. When doubtful points have been cleared up, the Treasury authorizes or refuses to accept the proposals in whole or in part. If additional expenditure is agreed upon the decision is referred to the esti mate clerk to note. On Oct. I, the Treasury sends a circular to the civil service and revenue departments requesting them to pre pare and forward their estimates of expenditure for the next financial year. These estimates are checked by the estimate clerk against his record of the accumulated authorizations and he calls attention to any changes for which no Treasury authority has been given or points out that some necessary provision has been omitted. He compares the estimates, item by item, with those of previous years. An item may have been increased by some temporary emer gency in the past and watchfulness is required to see that it is not continued on the same basis when the emergency is over. When for some time the actual expenditure has fallen considerably below the provision for specific items, pressure is applied for closer esti mating. A rise in the purchasing power of money will justify the estimate clerk in looking for lower estimates for stores and mate rials. Intelligent scrutiny of this kind has often proved extremely effective. But while economy must be considered, sufficiency must also be borne in mind. To frame unduly high estimates would weaken parliamentary control, add to the difficulties of the chan cellor of the exchequer, and result in an unnecessarily burdensome scheme of finance. On the other hand inadequate provision neces sitates a further application to parliament and disturbs the settle ment made by the year's budget. The estimates, approved by the Treasury with or without modification, are presented in detail to parliament.

The fighting services (the Army, Navy and Air Force) are no ex ceptions to the general rule that all expenditure must be approved by the Treasury, and the usual checks are applied throughout the year to such matters as pay and numbers of their civilian staff, etc. But the size of the forces, which governs the need for stores, uniforms, pay, rations, munitions and other chief heads of ex pense, is a matter of high policy settled in consultation with the chancellor and the cabinet. Technical requirements of the forces are obviously not susceptible to minute Treasury criticism. The estimate clerk's supervision is, in their case, little more than for mal. Each of the fighting arms is provided with a high financial officer whose duty it is to watch over financial interests within his department.

When all the estimates are sanctioned, a summary of these sup ply charges, as they are called, is laid before the financial secre tary and the chancellor of the exchequer. An estimate is next made of the consolidated fund charges, which are not voted annu ally by the House of Commons, but rest upon statutory foundations, until parliament shall otherwise determine. Such charges are the interest and management of the national debt, payments to the road fund and to local authorities, the civil list (a life-annuity set tled by parliament upon the sovereign at his succession in return for his surrender of the more valuable income from Crown lands), salaries and pensions of the speaker of the House of Commons, the judges, the comptroller and auditor-general, and others whose independence is shielded by depriving the House of an opportunity for criticism of their actions which would be given if their salaries were voted annually. Adding together the estimated supply charges and consolidated fund charges we have the total expenditure for which provision must be made.

It is now necessary to turn to the revenue side of the balance sheet. The revenue departments—the customs and excise, the in land revenue and the post office—furnish to the chancellor their estimates of receipts on the existing basis and on the basis of any changes which are proposed. In framing these estimates they take account of the state of trade, the growth of population, and other disturbing factors. After allowing for capital transactions such as interest or principal receipts from loans, and miscellaneous rev enue, the chancellor is able to strike a balance of estimated surplus or deficit. This will be modified by any changes approved by the cabinet in respect of policy, and a fresh balance-sheet is thus reached which may be adjusted on the revenue side by new taxes, increased rates of old taxes, repeal or reduction of existing taxes. The final result should show a balance on the right side, with due regard to contingencies not easily foreseen. The chancellor is now in a position to lay his draft budget before the cabinet and with their approval to unfold to the House of Commons the meas ures which are proposed to meet the financial needs of the nation in the course of the year. In times of peace he should pay his way and leave a small margin on the right side, but not too large a margin, or he will be pressed to reduce the burden of taxation forthwith. Lord Goschen's budgets were attacked by Lord Far rer on the ground that surpluses were "manufactured" by delib erate under-estimate of revenue and over-estimate of expenditure. Such a charge is more easily made than proved. If it were estab lished it would show that the chancellor was unusually courageous, confident of continuance in office, and ready to sacrifice immediate popularity to an uncertain future.

Parliament and the Budget.

As the control of the British Treasury over the preparation of the estimates is peculiar to Great Britain, so is the presentation of the budget to the legisla ture. Instead of being embodied formally in a budget bill, as is the case in most countries of Europe, where the whole scheme of revenue and expenditure for the year is submitted for the sanc tion of parliament, the British budget is merely explained to the House of Commons by the budget speech. The House is called upon to authorize part of the estimated expenditure—the supply charges—and to assent to such changes in the law as may be needed to give effect to the revenue proposals of the budget.At the beginning of each session the House sets up two great financial committees—the committee of supply and the commit tee of ways and means. Each is a committee of the whole House, sitting under a chairman instead of the Speaker. A former clerk of the House, Sir Reginald Palgrave, says "the exclusion of the King's emissary and spy—their speaker—was the sole motive why the Commons elected to convert themselves into a conclave called a committee, that they might meet together as usual, but without his presence." The speaker is no longer, if he ever was, an emis sary and spy of the sovereign, but the practice continues. It has the advantage that in committee discussion is more informal and conversational, since a member may speak more than once. Broadly speaking, the business of the committee of supply is to agree to the votes required, as shown in the estimates, for the service of each department. The committee of ways and means approves the issue from the exchequer of the money which is needed to make supply effective.

The British "Budget Day..

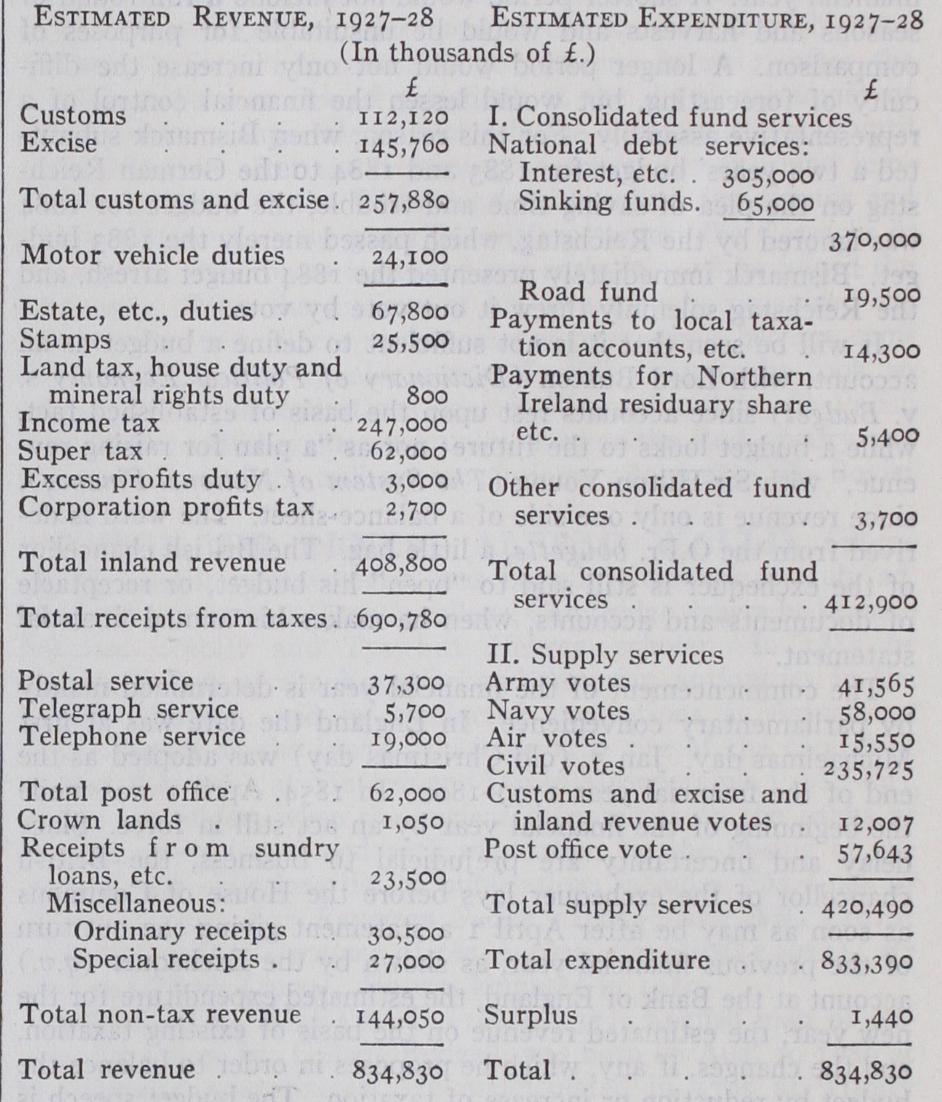

As soon as the committee of supply has voted a grant for the ensuing year, the committee of ways and means (i.e., the whole House) meets and the chancel lor lays before it his budget proposals on what is called the "Budget Day." He takes the opportunity to examine the financial situation of the country as disclosed by the exchequer receipts and pay ments of the previous year, gives the reasons for any appreciable variation between estimates and results for that year, expounds the changes in the national debt, states the forecast for the cur rent year, and discloses his plans for balancing the account. A white paper distributed just before his speech now enables him to abridge the statistical part of his exposition. The final balance sheet, after alterations proposed by the chancellor of the ex chequer, in 1927-28, was as follows: Immediately after the budget speech the budget resolutions are moved to give effect to the scheme of revenue proposed. For the most part taxes rest upon continuing statutes, but one direct tax (the income tax with its surtax) and one indirect tax (the tea duty) are voted for one year only in order to ensure that direct and indirect taxation are brought within the purview of the House every year even though there be no budget changes in respect of them.

The committee of supply, to which the estimates of expenditure are referred, can vote the grant proposed to it, or reduce it, or reject it, but may neither increase it nor annex a condition to it nor alter its destination. The House will only vote money on a recommendation from the Crown, signified through a minister. If it desires to increase a vote this can only be done by a supple mentary estimate, or by the withdrawal of the original estimate and its replacement by a new one. As rejection or even reduction of a vote would be a rebuff to the ministry and suggest want of confidence in the government, it would possibly lead to a general election. It is therefore very exceptional for discussions in supply to result in any change in the original estimates. When the com mittee has approved a grant, it reports its resolution to the House where the matter may be debated again with the speaker in the chair. If the House agrees with the committee's resolution the estimate goes to the committee of ways and means whose task it is to approve the provision of the necessary funds.

How the British Budget Becomes Law.

Upon the resolu tion of the ways and means committee is based a consolidated fund bill to authorize the issue out of the consolidated fund of sums to meet the grants in supply. The lump sums so authorized may not exceed the total of the grants previously voted in supply, and more than one consolidated fund Act is passed in each session. At the end of the session the final Consolidated Fund (Appropria tion) Act completes the grants required, and earmarks or appro priates to each service the money assigned to it in supply.From the committee of ways and means also springs the Finance Act which reimposes the annual taxes and makes any necessary changes in them or in taxation generally. After the passing of these two measures the budget is not only a plan but a legalized plan.

Twenty days before Aug. 5 are allotted to the committee of supply for the consideration of the estimates, including days spent on the vote on account and procedure in ways and means, but the government may allow three extra days if it thinks fit. At the end of the allotted days all outstanding votes are "guillotined" or put to the vote without discussion. Votes on account are in the nature of advances made to departments by special grant before there has been time to examine the estimates in detail in supply. As it is impossible for the committee of supply to consider all the estimates in the allotted time it is usual to allow the opposition to choose the order in which the votes shall be set down for dis cussion.

The estimates committee, consisting of is members drawn from all parts of the House, was first appointed in 1918. It may ex amine any estimate it chooses and send for persons, papers and records, but may not question the policy implied in the estimates. As policy to a large extent governs expenditure, and as the exami nation comes after the estimate has been presented, the discussions of this committee, like those in supply, and for the same reasons, have little effect upon the financial proposals of the year. The committee is purely advisory and the limitations under which it works deprive it of much practical influence.

When departments find their grants insufficient they put for ward supplementary estimates for further grants. Such estimates should always be jealously scrutinized, and enquiry should be pressed why the contingencies were not foreseen and whether ex penditure is so urgent that it cannot be postponed till the next budget. The estimates, if justified, must be passed through all their stages in time for the appropriation bill in order to avoid an excess of expenditure over the grant—a financial offence of the first magnitude. In cases where an excess has been incurred it is referred to a committee at the beginning of the next session in order that it may be fully justified and an excess vote passed to regularise the proceeding.

The finance bill and the consolidated fund bills are sent up to the House of Lords with a certificate by the speaker that they are money bills. By the Parliament Act, 1911, if a money bill, as defined in that act, be sent to the Lords at least one month before the end of the session, and is not passed by the House of Lords without amendment within one month, the bill shall, unless the House of Commons direct to the contrary, be presented to His Majesty and become an Act of Parliament on the royal assent being signified, notwithstanding that the House of Lords have not consented to the bill. The speaker consults two senior members of the House of Commons before giving his certificate, though the act makes his opinion sufficient. Complaint has been made that, as no one is infallible, the safeguard is not adequate, that a member of the House of Lords should be included in the panel, and that the statutory definition of a money bill needs amend ment to ensure that far-reaching changes are not improperly with drawn from the consideration of the Lords merely because they are inextricably interwoven with financial proposals and not easy to distinguish.

It will be seen that the budget, though theoretically the work of parliament, is dominated from start to finish by the executive government. The House of Commons accepts the estimates of expenditure as presented. It discusses the finance bill, and may succeed in making amendments designed to remove doubts or obviate hard cases. But the chancellor of the exchequer, though willing to smooth the passage of the measure by accepting small changes, will use his majority if there is any serious menace to the revenue which he requires. The dissent of the Lords is, like the veto of the Crown, no longer operative as a check upon the settlement of the budget.

Execution of the Budget.

A programme is one thing, its execution another. The House of Commons does not cease to con cern itself with the budget proposals when they have received its assent, but is interested to see whether they work out according to plan, and if not, why not. The collection of revenue and the expenditure on public services are in the hands of officials whose operations are subject to control and audit on behalf of the House. The comptroller and auditor general, a high officer of parliament, appointed by the Crown and independent of any de partment, is required to make a test audit of the revenue re ceipts, to audit the accounts of expenditure of each department, and to report to parliament any irregularities or other matters of interest arising out of the accounts. He must see that any surplus of grant over expenditure is surrendered to the national debt commissioners for the old sinking fund. It is also his duty to authorize all issues of moneys out of the exchequer and to take care that no such issues are made without parliamentary authority. His annual report is laid before the House and referred to the public accounts committee, which summons before it the account ing officers and officials of the Treasury and other departments for such explanations as it may desire, and reports its proceedings to the House. Any recommendations made by the public accounts committee are communicated to the Treasury for considera tion.The public accounts committee, like the estimates committee, is precluded from entering upon questions of policy, and it has often been urged that its control would be more effective in the interests of economy if it were aided by an inspector-general, whose function it would be to investigate wasteful expenditure wherever it can be found. The estimates are framed upon a non functional basis, under such headings as salaries, travelling ex penses, stores, etc. If they were set out on a cost-accounting basis, comparison would be more revealing of lack of economy. An experiment was made in this direction with the army esti mates, but was abandoned after a short trial for reasons which, so far as they have been made public, are far from convincing.

There is in England no formal act of parliament to close the accounts of the year. The exchequer account, being merely a cash or pass-book account, is made up when the Bank of England closes at 4 P.M. on March 31. The account audited by the comp troller and auditor general is the appropriation account. It in cludes all orders for payment drawn on or before March 31 whether or not they were cashed before April 1. Three months in the case of civil departments and six months in the case of the fighting services are allowed for the purpose of including all such transactions. The totals of the appropriation account there fore differ slightly from those of the exchequer account. It is the appropriation account which is dealt with by the public accounts committee, and when this account is closed any further receipts or payments, whether proper to the past or present year, are in cluded in the accounts of the year in which they are encashed.

In some countries the accounts are kept open until all the re ceipts and payments proper to the year can be included. This sometimes requires the accounts to be kept open for several years. The British system has the advantage of closing the ac counts promptly, and with approximately close results, outweigh ing the advantages of the theoretically more exact method.

The serious political, constitutional and financial changes brought about by the World War severely jolted the framework of the budgets of governments all the world over. But it must be emphasized that the essentials of a budget are few in number (i.) an estimate of the expenditure required for discharging the functions of the authority concerned, brought into relation with (ii.) an estimate of the revenues out of which the expenditure is to be defrayed during the budgetary period. It follows that assets and liabilities find no place in the budget except in so far as they involve receipts and payments within that period. A budget does not afford a picture of the financial condition of a government. It does not show the total cost of governing a country, since there may be subordinate local governments, or a superior federal government as in Germany, the United States, Australia, Canada, India, South Africa, etc. The demarcation be tween such varied authorities is determined by the law and custom of the constitution or by historical circumstances.

The most fertile source of fallacies in statistics is the compari son of dissimilar things as if they were alike. It would for exam ple be grossly misleading to compare the cost of government in a highly centralized kingdom, like Italy (where under the Fascist regime only sanitary and social services are left to local govern ment), with the federal budget of the United States, where 48 states, largely autonomous, with their own tax laws, include large cities, boroughs, urban and rural districts each with its own budget and financial system. Payments between these authorities are in extricably interwoven, and an addition of all their expenditures would include several items two or three times over. A budget may be accompanied by a mass of documents, accounts, financial memoranda and explanations designed to show the financial situ ation in its entirety. From the budget itself no more can be extracted than the limited information which it contains for its limited purpose.