Babylonian and Assyrian

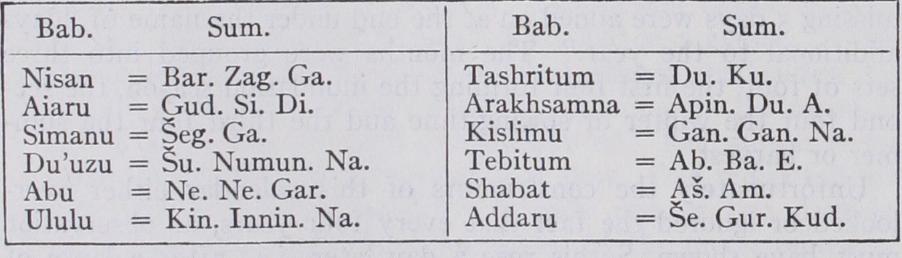

BABYLONIAN AND ASSYRIAN Babylonian, from 2000 B.C. Onwards.—The Babylonian calendar imposed by the kings of the First Dynasty of Babylon, on all the cities immediately under their rule, was adopted by the Assyrians at the end of the second millennium B.C., was used by the Jews on their return from exile, and was widely used in the Christian era. This calendar was equated with the Sumerian cal endar in use at Nippur at the time of the Third Dynasty of Ur (about 2300-2150 B.c.) in the following manner: These were lunar months, and in general their length was 30 days; in historical times regular watch was kept for the new moon, and if that fell on the 3oth of a month, then the day automati cally became the first of the next month, and all officials were apprised of the fact. In order to prevent too serious a derange ment of the seasons owing to the discrepancy between i 2 lunar months and the solar year, a month was intercalated; the inter calary month might be a second Elul (Ululu) or a second Adar. Such intercalations were, in the late period, regularly devised within a cycle; in the Seleucid period and earlier, from 382 B.C., the cycle was 19 years, from 504-383 it was 27 years, from 528- 505 it was eight years. Before the reign of Darius the intercala tion was not based on any fixed cycle, but was inserted when the astronomers advised the king that it was necessary, the object being, it has been suggested, that the first of Nisan, with which the year always began, should not fall over a month later than the spring equinox, and not more than a month before it. It has been calculated that the actual variation in terms of the Julian calendar amounts to about 27 days. Nisan is therefore roughly March–April, but in certain extreme cases April–May.

The meanings of the names of the months cannot be ascertained with certainty. Nisannu seems to mean "sacrifice," Aiaru "blos som," Simanu "the fixed, appointed time," whether in relation to some ritual observance is not clear, Du'uzu is a form of Tammuz due to sound changes and the month was so named because vege tation had left the parched earth then, Arakhsamna is "the eighth" month. Since these names belong to the Akkadian language, it is probable that they arose in Babylonia, but it is conceivable that they were already known to the earliest people of Semitic speech before they entered the Euphrates valley.

The month was divided into unequal periods by days with special names, the first, arhu, the seventh, sibutu, the i 5th, sabattu, the 28th, bubbulu, and the 3rd., 7th., 16th., nubattu, "rest"; but there was no system of continuous reckoning in weeks of seven or any other number of days. The day was divided into six watches, three for the day, three for the night, the first being called "sunrise," napakh Shamshi, "siesta," mus lain, and "sunset," ereb Shamshi, or "evening," lilati; the second "peeping (of the stars)," bararitu, "middle," qablitu, and "the time of dawn," sat urri. Time was reckoned in double hours, 12 to the day, and it is probable that the astronomers, if not all others, reckoned day as beginning with sunset. The hours con sisted of 3o smaller divisions. Exact reckoning was secured by measuring weights of water passing through a pierced bowl—a water clock.

Other calendars were in use in the seventh century within the Assyrian empire. Thus a month Kanun, which was probably de rived from a Syrian calendar, is testified to by a man's name. The Elamites had a calendar of their own occasionally used in Assyria.

Early Assyrian, Before 1000 B.C.

The calendar regularly used in Assyria before the tenth century, and even after that date occasionally, was not derived from Babylonia. The month names are: (I) Qarrate, (2) Tan( ?) marte, (3) Sin, (4) Kuzalli, (5) Al lanate, (6) Belti-ekallim, (7) Sarate, (8) Kinate, (9) Mukhur (to) Ab sharrani (i i) Khibur, (5 2) Sippim. These months are differently equated by cuneiform scribes with Babylonian months; one list makes Qarrate equivalent to Addaru, the other to Shabatu, i.e., either Feb.–March, or Jan.–Feb. The difference may perhaps have arisen from the lack of intercalation in the Assyrian calendar over a long space of time. It is to be noted that there is no cer tain occurrence of an intercalary month in this Assyrian calendar.The meanings of the names are in this instance also known in a few cases. The first month derived its name from a festival in which the limmu or eponymous officer of the year took part, per haps connected with the drawing of lots. The second, Tanmarte, if correctly read, is the month of "shining forth," the third is the month of the moon-god, the fourth perhaps "of gourds," the fifth, "of terebinths," the sixth is named after a form of Ishtar called "the Lady of the Palace," the ninth is named after a special offer ing made to gods when entering holy buildings. The origin of this calendar must lie in the times before the Assyrians entered the Tigris valley. It was not the Subaraean calendar, for the three known Subaraean month-names were Ari, and "the month of Adad" and "the month of Nergal." This Assyrian calendar was used over an extensive area at the time of the Third Dynasty of Ur, for it occurs on the tablets from Caesarea (Mazaca) at that time, together with other month names, Kiratim, "of gardens," Tinatim, "of figs," and Narmak-Ashur, "the libation of Ashur." This last month was the same as Kinatim, and was only tempo rarily used, the other two also may represent a change in nomen clature. But it had no currency in the middle Euphrates, for in the kingdom of Khana, immediately north of Babylonia, still an other calendar was used, including the names Kinunu, "stove" (the later Kanun), Birissaru, Teritum, Belitbiri, "the lady of vision," Igi-kurra (a divine title) ; the order of these months is unknown, and it is uncertain whether this calendar was used outside Khana. Still other month names must have been used elsewhere, for on documents of the First Dynasty of Babylon there occur the names Tiru, Nabru, Sibutu, Rabutu (equivalent to Nisan), Mamitu, and Isin-Abi.

The most striking feature of the Assyrian calendar is its com mencement, not at the spring equinox, but one or even two months before. This feature proves a complete independence of any astro nomical observation when the calendar was first formed, but its exact cause cannot be defined. The general meanings of the month names, with the exception of the third and sixth, seem to show that this was an agricultural calendar, based simply on the farm ing year ; the month names closely connected with ritual observ ances may have been adopted long after the origin of the actual calendar itself.

Sumerian Calendars.—The calendar used by the kings of the Third Dynasty of Ur (see above), and always subsequently kept as "ideograms" for the later month names, seems to have origi nated as the local calendar of the city of Nippur at a time when various other city-calendars were in use. The meanings of these month names may be roughly as follows : (1) "month of the dweller of the sanctuary," (2) "month of the leading out of the oxen," (3) "month of brick-making," (4) uncertain, (5) "month of setting the fire," (6) "month of a (certain) festival of Ishtar," (7) "month of the sacred place" duku, (8) "month of opening the irrigation canals," (9) "month of ploughing (?)," (Io) named after a religious festival, (I i) "month of emmer-grain," (12 ) "month of corn-harvest." An intercalary month DIR.SE.GUR KUD. was inserted, but no fixed principle can be observed.

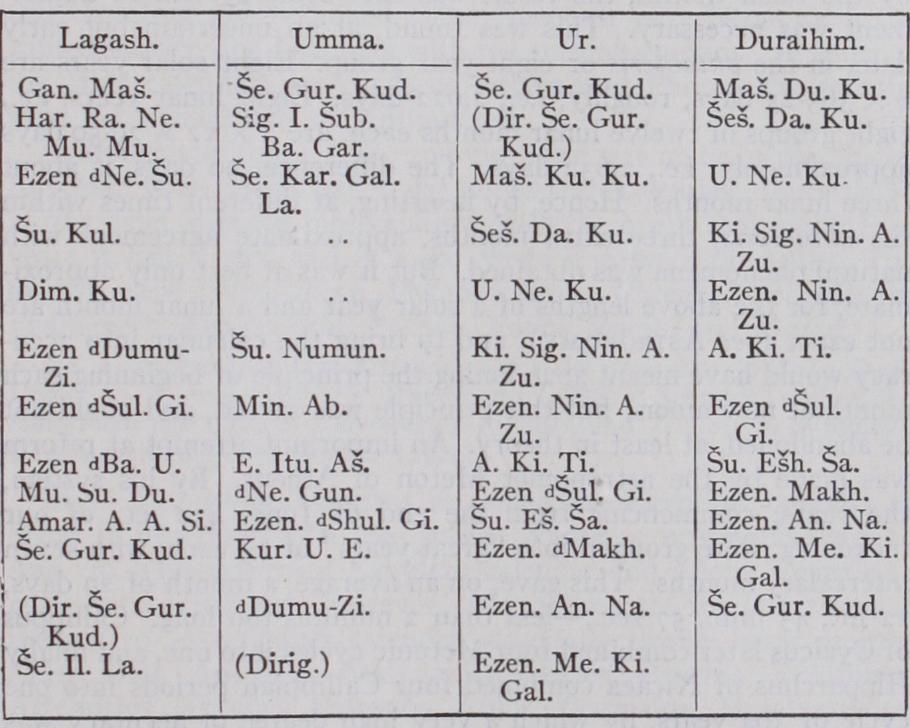

The Nippur calendar was not used at Lagash, Umma or the ancient town which occupied the site of the modern Duraihim, under the Third Dynasty of Ur, i.e., about 2300-2150 B.C. The month names at Lagash in use at the time of Sargon of Agade, i.e., before 2 500 B.C., number about 25, but not all these names be longed to a calendar; some are merely descriptions of a month as that in which sheep-shearing took place, or when men arrived from a certain place. The fixed month-names at Lagash, Umma, and Duraihim, where two calendars were in use at the same time, for the Third Dynasty of Ur period were :— Those names enclosed in brackets are the names of the inter calary months marking the position in the calendar when inter calated. All, or nearly all, these names are derived from specific festivals and ritual acts. The lists are sufficient to prove three points : (I) names were borrowed by one local calendar from an other at this time, (2) the time of the festivals in the different cities must have varied, for it is inconceivable that the festival of Shulgi, the second king of the Third Dynasty of Ur, could ever have been in the same month at Umma and Lagash, (3) that the intercalation in different towns was independent. We are not in a position to explain the complicated calendar of this period by the position at an earlier date ; the earliest month names, from the pre-Sargonic or early Sumerian period offer even greater difficul ties, and are also connected with religious festivals and ritual acts. Of all the Sumerian calendars, that of Nippur, which is derived from agricultural habits, looks the most primitive, but the point must remain quite obscure. Some local Sumerian month-names survived until the period of the First Dynasty of Babylon, and the reduction of the confusion in this matter to comparative order was probably due to Hammurabi. (S. Sm.) BIBLIOGRAPHY.-F. X. Kugler, Sternkunde and Sterndienst in Babel Bibliography.-F. X. Kugler, Sternkunde and Sterndienst in Babel (1914-24) ; B. Landsberger, Der kultische Kalender der Babylonier and Assyrer (Leipzig 1915).