Barge Canals

BARGE CANALS Choice of Line.—In laying out a line of canal the engineer is more restricted than in forming the route of a road or a railway. Gradients being inadmissible, the canal must either be made on one uniform level or must be adapted to the general rise or fall of the country through which it passes by being constructed in a series of level reaches at varying heights above a datum line, each closed by a lock, or some equivalent device, to enable vessels to be transferred from one to another. To avoid unduly heavy earth work, the reaches must follow the bases of hills and the windings of valleys, but from time to time it will become necessary to cross a depression by the aid of an embankment or aqueduct, while a piece of rising ground or a hill may involve a cutting or a tunnel. Sharp bends must be avoided, the permissible radius of curves depending on the dimensions of the vessels for which the canal is designed and the width of the waterway.

Aqueducts.

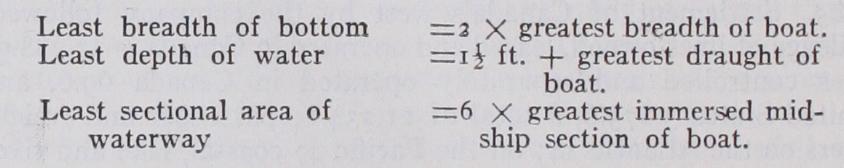

Brindley took the Bridgewater canal over the Irwell at Barton by means of an aqueduct of three stone arches, the centre one having a span of 63ft., and Thomas Telford ar ranged that the Ellesmere canal should cross the Dee valley at Pont-y-Cysyllte partly by embankment and partly by an aque duct i,000ft. long and 1 2 7 f t. above the river, consisting of a cast iron trough supported on iron arches with stone piers. In the building of the Manchester Ship Canal it became necessary to replace Brindley's aqueduct at Barton, which was only high enough to give room for barges, by a swing aqueduct, the first of its kind, to allow shipping to pass in the canal under it. (See MAN CHESTER SHIP CANAL.) Tunnels.—One of the earliest canal tunnels was made in 1766-77 by Brindley at Harecastle on the Trent and Mersey canal. It is 2,88oyd. long, I2ft. high and 9ft. wide, and has no towpath, the boats being propelled by men ("leggers") lying on their backs and pushing with their feet against the tunnel walls. This tunnel was in 1928 out of use owing to subsidence due to coal workings. Traffic is now worked through a second tunnel, parallel to this but I 6f t. high and I 4f t. wide, including a tow path, which was finished by Telford in 1827. Standedge tunnel, on the Huddersfield canal, is over three miles long, and is still (1928) worked by "leggers." Tunnels on Continental canals, es pecially in France, are numerous and of much larger dimensions than those on English canals. One, on the St. Quentin canal, 6, 200yd. long, is 26 a f t. wide and 2 2 3 f t. high. The Royaulcourt tunnel on the Nord canal (completed 19 23) is 4, 7 5 7Yd. long, 33ft. wide and 28ft. high, with an enlarged passing place in the middle. The largest canal tunnel in the world is that at Rove (fig. 8) near Marseille. (See SHIP CANALS below.) Dimensions.—The dimensions of a canal, apart from consid erations of water-supply, are regulated by the size of the vessels which are to be used on it and, to some extent, by their speed. According to J. M. Rankine (Manual of Civil Engineering), the depth of water and sectional area of waterway should be such as not to cause any material increase of the resistance to the motion of the boats beyond what would be encountered in open water, and he laid down the following rules as fulfilling these conditions :— Rankine was considering the small barges in use in his day, but his proportions are still very generally accepted. In large modern canals it is, however, usual to allow a greater clearance than i8in. under the boat, the amount increasing with the size and the speed of the vessels (see HYDRAULICS and WAVE). The ratio of wetted cross-section of the canal to the immersed cross-section of boat varies in modern canals from 4 :1 to 6.5 :1. The larger the ratio, the less will be the erosion of the banks, which increases with the speed of vessels. The ordinary inland canal in England is commonly from 18 to Soft. wide at the bottom, 3o to 45ft. at the water level, with a depth of 31 to 5 feet. The early continental canals were a little larger, being usually designed for boats of ioo tons or more. In some recent French canals a depth of 8 2 f t. and a width of 3 9 z f t. at a depth of 6 z f t. have been adopted for the waterway; and the locks, designed for two barges in line, are 28oft. long and 19.7 f t. wide. The tendency on all continental waterway systems has been, since the last decade of the 19th century, to increase the ruling dimensions of both canals and canalized rivers in order to allow a larger proportion of the craft using the great free rivers, such as the Rhine, to navigate the locked waterways. In Germany, for instance, canals have been constructed with a width of 69f t. and upwards.

Canal Banks, etc.

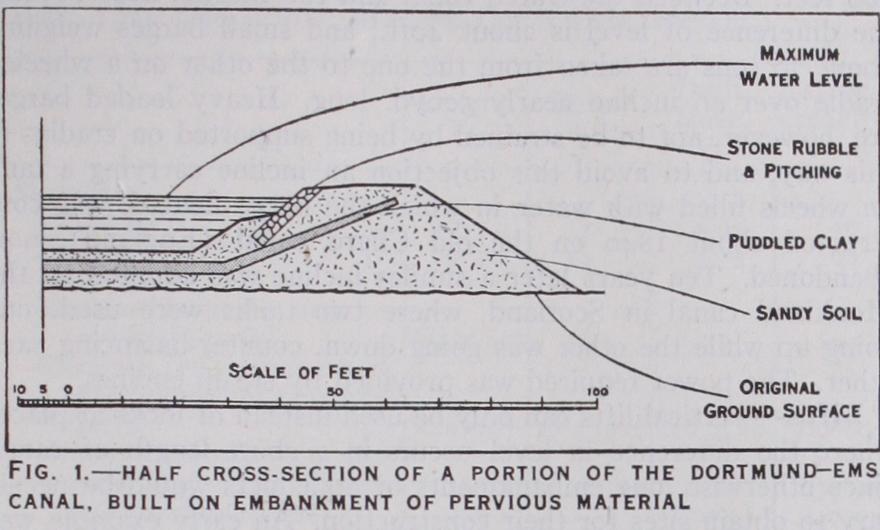

To retain the water in porous ground, and especially on embankments, a watertight lining of puddle clay must be provided on the bed and sides of the channel, or some other means, such as a lining of concrete, adopted to prevent leak age (fig. I ). The difficulty of maintaining canals on embankments is always a serious one even on banks of quite moderate height.

The

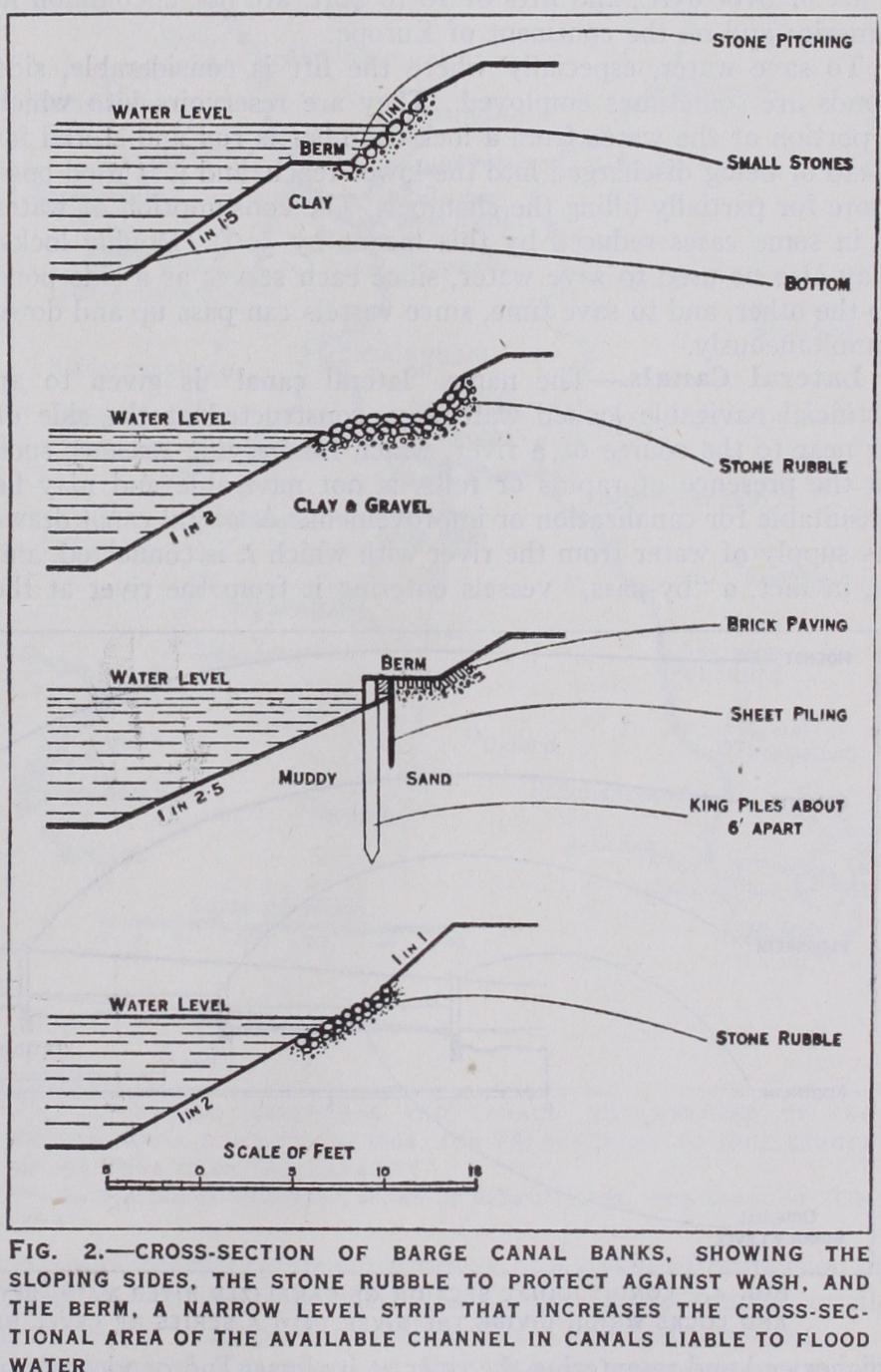

sides of canals are usually sloped, the angle varying with the nature of the soil from i in i to in 3 or even flatter. In rock cuttings the sides are often nearly vertical. To prevent the erosion of the sides by the wash from boats it is usual to protect the banks at and near the water line by stone rubble or pitching, concrete or brick paving or fascine work, in some cases com bined with continuous piling (figs. i and 2). A berm—a narrow level strip along the bank at or just under the water level—is sometimes formed in the bank to minimize the effect of wash (fig. 2) .

Water Supply.

If there be no natural lake in the district for storage and supply, or if the engineer cannot draw upon some stream of sufficient size, he must form artificial reservoirs in suit able situations. They must be situated at such an elevation that the water from them may flow, through feeders, to the summit level of the canal; and, if the expense of pumping is to be avoided, they must command a sufficient catchment area to supply the loss of water from the canal by evaporation from the surface, percolation through the bed, leakage at gates and lockage. Since the consumption of water in lockage increases both with the size of the locks and the frequency with which they are used, the difficulty of finding a sufficient water supply may put a limit to the density of traffic possible on a canal or may prohibit its locks from being enlarged so as to accommodate boats of the size necessary for the economical handling of the traffic under modern conditions. It may be pointed out that the up consumes more water than the down traffic. An ascending boat on entering a lock displaces a volume of water equal to its submerged capacity. The water so displaced flows into the lower reach of the canal and, as the boat passes through the lock, is replaced by water flowing from the upper reach. A descending boat in the same way dis places a volume of water equal to its submerged capacity, but in this case the displaced water flows back into the higher reach where it is retained when the gates are closed.Some economy of water in locking may be effected by using side ponds (see below) ; but, nevertheless, it is necessary in the case of some canals to resort to pumping in order to supply de ficiencies, particularly in dry seasons and on summit levels. There are many canal pumping installations in France, Germany and England. Electric power has been utilized for pumping in some plants.

Waste-weirs and Stop-gates.

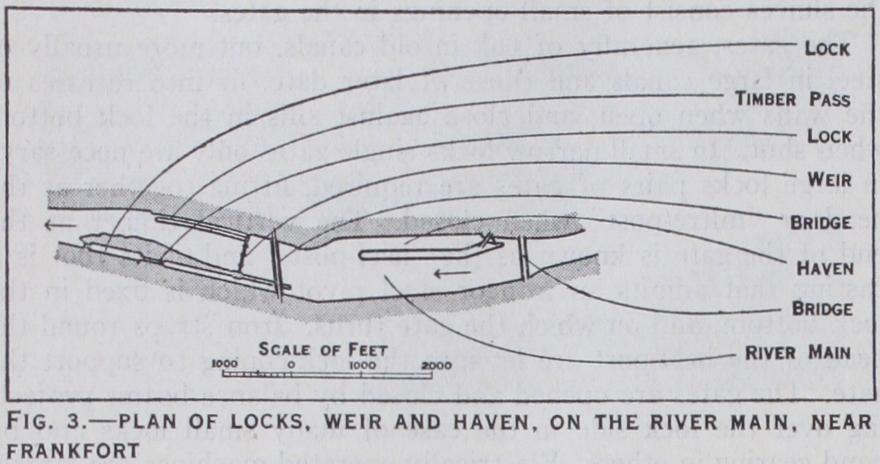

An essential adjunct to a canal is a sufficient number of waste-weirs to discharge surplus water accumulating during floods. The waste-weirs are placed at the top water-level of the canal, so that when a flood occurs the water flows over them and thus relieves the banks. Culverts, when constructed under a canal embankment to pass streams and flood water, must be of ample dimensions (see WEIR).Safety or stop-gates are necessary at intervals for the purpose of dividing the canal into isolated reaches so that, in the event of a breach, the gates may be shut, and the discharge of water confined to the reach intercepted between two of them. In broad canals these stop-gates may be formed like lock gates ; or in small works they sometimes consist of thick planks slipped into grooves. Self-acting gates have been tried but have not proved trustworthy. Stop-gates consisting of a horizontally framed steel shutter of the width of the canal, suspended from an overhead bridge and counterbalanced, are used on some modern canals: these can be lowered by means of gearing into grooves built in the canal sides.

Locks.

In large locks, as well as in most of the small locks of modern construction, the sluices by which the lock is filled or emptied are carried through the walls, but in many old locks the sluices consist of small openings in the gates.The gates, generally of oak in old canals, but more usually of steel in large canals and those of later date, fit into recesses of the walls when open, and close against sills in the lock bottom when shut. In small narrow locks single gates only are necessary; in large locks pairs of gates are required, fitting together at the head or "mitre-post" when closed. The vertical timber at the end of the gate is known as the "heel-post," and at its foot is a casting that admits an iron or steel pivot which is fixed in the lock bottom, and on which the gate turns. Iron straps round the head of the heel-post are let into the lock-coping to support the gate. The gates are opened and closed by balance beams project ing over the lock side in the case of many small locks and by hand gearing in others. Electrically operated machines are largely employed on canals of modern construction in America and on the continent of Europe for opening and closing lock gates and sluices. (See also DocKs.) In order to economize water, canal locks are made only a little larger than the largest vessel they have to accommodate (see below: Canal Barges and Modern Canal Development). In many canals constructed since 1900, however, provision is made for admitting a train of barges; such long locks have sometimes intermediate gates by which the effective length is reduced when a single vessel is passing (fig. 6) .

The lift of canal locks, i.e., the difference between the levels of adjoining reaches, rarely exceeded 12ft. up to the end of the 19th century and in some locks the lift is as little as i If t. The modern practice is to build one lock with high lift in preference to a flight of shallower locks in all cases where the configuration of the ground and considerations of water supply allow of this being done. In Germany, for instance, there is at least one lock with a lift of over 65f t., and lifts of 20 to 4oft. are not uncommon in America and on the continent of Europe.

To save water, especially where the lift is considerable, side ponds are sometimes employed. They are reservoirs into which a portion of the water from a lock-chamber is run and stored in stead of being discharged into the lower reach, and it is used once more for partially filling the chamber. The consumption of water is in some cases reduced by this means by 50%. Double locks, may also be used to save water, since each serves as a side pond to the other, and to save time, since vessels can pass up and down simultaneously.

Lateral Canals.

The name "lateral canal" is given to an artificial navigable locked waterway, constructed at the side of or near to the course of a river, which for varying reasons, such as the presence of rapids or falls, is not navigable and may be unsuitable for canalization or improvement. A lateral canal draws its supply of water from the river with which it is connected, and is, in fact, a "by-pass," vessels entering it from the river at the to locks where many small pleasure boats have to be dealt with, is to fit the incline itself with rollers, upon which the boats travel; and at Boulter's lock on the Thames an electric conveyor is pro vided on the inclines. In some early cases boats were conveyed on a wheeled trolley or cradle running on rails. This plan was for merly in use on the Morris canal (New Jersey), built in 1825-31, in the case of 23 inclines, the rise of each varying from 44 to 100 feet. Between the Ourcq canal and the Marne, near Meaux, the difference of level is about 4oft., and small barges weighing about 7o tons are taken from the one to the other on a wheeled cradle over an incline nearly 5ooyd. long. Heavy loaded barges are, however, apt to be strained by being supported on cradles in this way, and to avoid this objection an incline carrying a tank on wheels filled with water in which the barge floated, was con structed about 1840 on the old Chard canal (England), now abandoned. Ten years later a similar incline was adopted on the Monkland canal in Scotland, where two tanks were used, one going up while the other was going down, counter-balancing each other. The power required was provided by steam engines.

Lifts.

Vertical lifts can only be used instead of locks at places where the difference in level occurs in a short length of canal, since otherwise long embankments or aqueducts would be neces sary to obtain sites for their construction. An early example was built in 1809 at Tardebigge on the Worcester and Birmingham canal.At Anderton a lift was erected in 1875 to connect the Weaver navigation with the Trent and Mersey canal, which at that point is 5oft. higher than the river. The lift is a double one, and can deal with barges up to 10o tons ; the vessels are water-borne in a wrought-iron tank 7 Sf t. long and 15 if t. wide. Until 1908 the tanks were raised and lowered by means of hydraulic rams but in that year electric power was substituted, each of the two tanks being counter-balanced by weights and operated by electric winches. (See J. A. Saner, Proc. Inst. C.E., vol. clxx., 1910.) A similar hydraulic lift, completed in 1888 at Fontinettes on the Neuffosse canal in France, can accommodate vessels of 30o tons, a total weight of 785 tons being lifted 43ft.; and a still larger example on the Canal du Centre at La Louviere in Belgium, built in 1888, has a rise of soft., with tanks that will admit vessels up higher end and re-entering the river at its lower end or vice versa. There are many examples of lateral canals in Canada, notably those connected with the river St. Lawrence, also in the United States and on the continent of Europe, particularly in France.

Inclines.

Economy of water can be effected by the use of inclined planes or vertical lifts in place of locks. In China rude inclines appear to have been used at an early date, vessels being carried down a sloping plane of stonework by the aid of a flush of water or hauled up it by capstans. On the Bude canal (Eng land), now abandoned, this plan was adopted in an improved form for small boats. Another expedient, often adopted as an adjunct to 400 tons, the total weight lifted amounting to over 1,000 tons This lift, and three others of the same character, which, however, were not completed until 1921 although commenced many years before, overcome the rise of 217ft. which occurs in this canal in the course of 41 miles.The La Louviere lifts are the only examples constructed in Europe since 1899, when the Henrichenburg lift on the Dortmund Ems canal was opened. The latter raises barges of 60o tons carry ing capacity through a height of 46 feet. The single tank is 223 x 28ft. internally, the depth of water being 8 feet. The operation of the lift is effected by an ingenious arrangement of balancing floats immersed in deep tank-shafts. At Peterboro, Ontario, there are two hydraulic barge-lifts constructed about 1908. Neither lifts nor inclines are in use in the United States.

Generally speaking, canal constructors, both in America and on the continent of Europe, have, for many years, shown a decided preference for high-lift locks to either mechanical lifts or inclines.

Canal Barges.

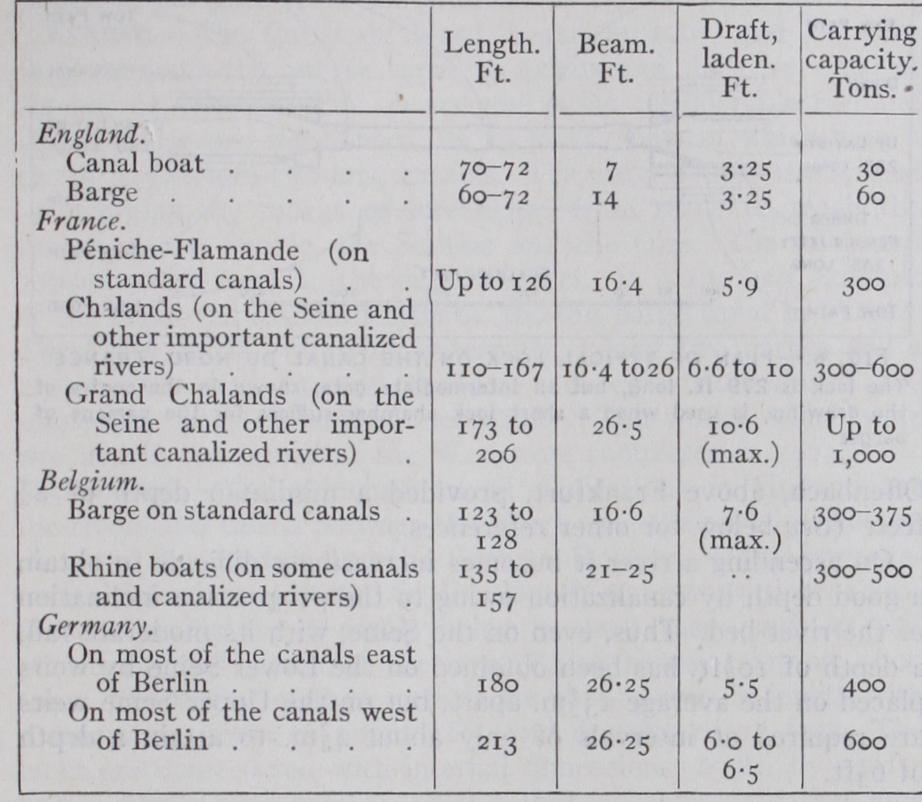

The following table gives particulars of some of the typical barges in use on European canals and canalized rivers. (See also below: Modern Canal Development.) Speed of Haulage on Canals.—The horse or mule walking along a towpath and drawing or tracking a barge by means of a towing rope, still remains the typical method of conducting traffic on the smaller canals, not only in England, but on the continent of Europe. Horse traction is very slow ; the maximum speed is about 3m. per hour, and the average, which, of course, depends largely on the number of locks to be passed through, much less.

At speeds over c. 3m. per hour the "wash" of the barge begins to cause erosion of the banks and thus necessitates the em ployment of protective measures which are commonly provided in all canals of modern construction (see above). Moreover the tractive effort required to haul a barge increases with the speed at a rate which much exceeds a direct proportion; and careful trials carried out in France and Germany since 1909 show that, on barge canals, a speed greater than 3m. or 3-1m. per hour is uneconomical as regards both haulage and maintenance costs. The speed on French canals is limited to five km. (3.11m.) per hour; and a tug or tractor with its tow of barges usually does from 13 to 18m. per day on the average (including going through locks). The speed limitations (1928) on German, Belgian and Swedish canals are on a par with the French. It may be noted in passing that, in towing or hauling barges on a canal, the tractive force per barge decreases with the number of barges in tow.

Tugs and Self-propelled Barges.

Steam towage was first employed on the Forth and Clyde canal in 1802, when a tug-boat fitted with engines by W. Symington drew two barges for a dis tance of 191 miles in six hours in the teeth of a strong headwind. Tugs are only economical where there are either no locks, or locks either large enough to admit the tug and its train of barges simultaneously or spaced at long intervals : otherwise the advan tages are more than counter-balanced by the delays in locking. On the Bridgewater canal, which has an average width of Soft. with a depth of silt., and has no locks for its entire length of 4o miles except at Runcorn, where it joins the Mersey, tugs tow four barges, each carrying 6o tons, at a rate of nearly 3m. per hour.On the Aire and Calder navigation, where the locks have a minimum length of 21 sf t., a large coal traffic is carried in trains of boat-compartments. The boats are nearly square in shape, ex cept the leading one which has an ordinary bow. They are coupled together so that they can move both laterally and vertically ; and a wire rope in tension on each side enables the train to be steered. No boat crews are required, the crew of the tug regulating the train. Each compartment carries 35 tons, and the total weight in a train varies from 700 to 90o tons. On the arrival of a train at Goole the boats are detached and discharged into sea-going ships by means of cradles and hydraulic hoists.

Barges self-propelled by steam-power were first tried on the Forth and Clyde canal by Symington as early as 1789. Since 1910 the use of internal combustion motors as a means of propulsion on canals has considerably increased. Even on the smaller canals many barges in all parts of the world are now self-propelled.

Mechanical Traction on Canals.—In several long tunnels and deep rock cuttings in France where no towpaths have been provided, recourse has been had to a submerged chain which is passed round a drum on a tug; this drum is rotated by steam power and thus the tug is hauled through the reach. The same system is in use on the Regents Canal (London) for towing barges through the Islington tunnel. In the Mont-de-Rilly tunnel, at the summit level of the Aisne-Marne canal, a system of cable-traction was established in 1893, the boats being taken through by being attached to an endless travelling wire rope supported by pulleys on the towpath.

Small locomotives running on rails along the towpath were tried, towards the end of the 19th century, on the Shropshire Union canal, where they were abandoned on account of practical difficulties in working. About the same time similar experiments were made on canals in France and Germany, where, however, the financial results were not satisfactory. On portions of the Teltow canal, joining the Havel and the Spree, electric tractors run on rails along both banks, taking their current from an over head conductor; they attain a speed of an hour when hauling two 600-ton barges. Electricity is also utilized for working the lock gates and for various other purposes along the route of this canal. Electric tractors are also employed on the Charleroi canal (Belgium), and petrol tractors on the Bourgogne canal (France).

Since about 1923 on the Canal du Nord, between St. Omer and Janville, electric tractors running on rails on the bank haul 300 ton barges in groups of two or more. On the Calais-St. Omer section light caterpillar road tractors of the Citroen type were established in 1925 for hauling two or more loaded barges. Elec tric rail tractors are also employed on sections of the St. Quentin and other canals in the north of France, and were experimented with on the Liege-Antwerp canals in Belgium in 1919, but soon abandoned. Mechanical traction has not developed in so marked a manner as towage; and, on the whole, the results do not show any considerable decrease in cost compared with other haulage or towage, nor has the speed of the boats been materially increased. The cost of installing and working a system of electric rail trac tion is only justified in cases where, as on some of the canals in the north of France, the traffic is intense ; on the St. Quentin canal the traffic intensity before the war amounted to between six and seven millions of tons per annum and in 1926 had nearly returned to six millions. On the Nord system light tractors are preferred for the less busy sections. Electric capstans are provided at many French and a few Belgian and Dutch canal and river locks for facilitating the passage of barges. In some cases little use appears to be made of these facilities.