Byzantine Music

BYZANTINE MUSIC. The name Byzantine is usually given to the music of the mediaeval Greek Orthodox Church. Our knowledge of it rests partly on the writings of theorists, partly on the hymns themselves preserved in liturgical manu scripts. The earlier musical signs or neumes have survived from the loth century A.D., but their exact interpretation is not yet possible. In the 13th century the Round or Hagiopolitan notation was invented, which can be deciphered. The signs expressed in tervals; the initial signature showed the Mode and gave the starting-note. Byzantine music was vocal and was sung by a pro fessional cantor or by a trained choir in unison. No instruments were used in the Greek Church ; but at the Palace of the Em perors at Constantinople there were two organs in the 15th cen tury; and they were always used to accompany the choir on state occasions.

St. John of Damascus, in the 8th century, is said to have given Byzantine musical theory a definite form. Possibly he fixed more accurately the eight mediaeval modes, which were common to the Eastern and Western churches, and exemplified them in his own compositions. It is likely that many of the simpler melodies, which have come to us in the Round notation, had been handed down with slight variations from the time when most of the hymns were written—the poet being also the composer—that is, from the 8th, 9th and loth centuries.

We cannot say with from what sources the Eastern Church derived her music before the 8th century. It is usually assumed that the prevalent Graeco-Roman type of melody formed the basis in early Christian times, with a free inclusion of Hebrew tunes, borrowed along with the Psalms and Canticles. But the other branches of the Christian church in the East, particularly the Syrian and, later, the Armenian, probably contributed some thing also. After the conversion of the East Slavonic races, their churches took over the Byzantine musical system.

Byzantine music had no fixed rhythm or regular division into bars or measures. The tune follows the words according to the stress accents, ignoring the ancient quantities of the vowels, and as the text is nearly always rhythmical prose (like the Psalms in both the Greek and English Bibles) the total effect is a rather lively and melodious recitative rather than a tune in the modern sense.

The Modes are numbered in a different order from the Gre gorian, which they otherwise resemble, and exhibit several by f orms. The classification as Authentic and Plagal had more the oretical than practical value. The normal types require the fol lowing initial and final notes. Authentic—Mode I., a or d ; Mode II., b or g, Finalis e; Mode III., c' or a, Finalis f ; Mode IV., theoretically d', but usually g. Plagal—Mode I., d ; Mode II., Pl., e; Mode III., Pl. (also called Barys or Grave Mode) f, rarely low B-flat ; Mode IV., Pl. g. All these seem to have used the diatonic vocal scale with Just Intonation.

In the 15th century Byzantine music becomes more ornate and florid, while the notation adopts many subsidiary signs, as guides to ececution and expression. Some of these had already been invented by the famous singer John Cucuzeles about 13oo ; and this ornate notation is of ten called Cucuzelian. In the 16th and early 1 7th centuries the art declined ; and the notation was only known to a few precentors. A revival took place about 1670, the work of a school of composers, whose centre was the Patri archal church at Constantinople. These musicians were accus tomed to Oriental music, and some of them composed Turkish songs. Consequently, though the notation does not differ greatly from the I 5th century, the spirit of the music is de cidedly Eastern; and the Turkish scales, with their irrational intervals, were probably employed, at any rate in new compo sitions.

This Graeco-Oriental school lasted until 1821, when Chrysan thus, an Archimandrite, introduced a simplified notation, also con sisting of interval-signs, in which the music could be printed. Although Chrysanthus had studied Western theory, he accepted the Oriental scales and invented symbols to describe them. His principles seem to have been too complicated for general use ; and complete uniformity of rendering was not secured. The Chry santhine notation is still in use ; and the traditional manner of singing, of ten painfully nasal, with a drone or holding-note kept by one or two voices, may be heard in most of the smaller Greek churches and monasteries.

It is a common mistake to believe that this modern system is the same as mediaeval Byzantine music. Since 1870 some of the larger city Churches have introduced four-part unaccompanied singing, perhaps under Russian influence. But more recently there has been a set-back in favour of the Chrysanthine usage.

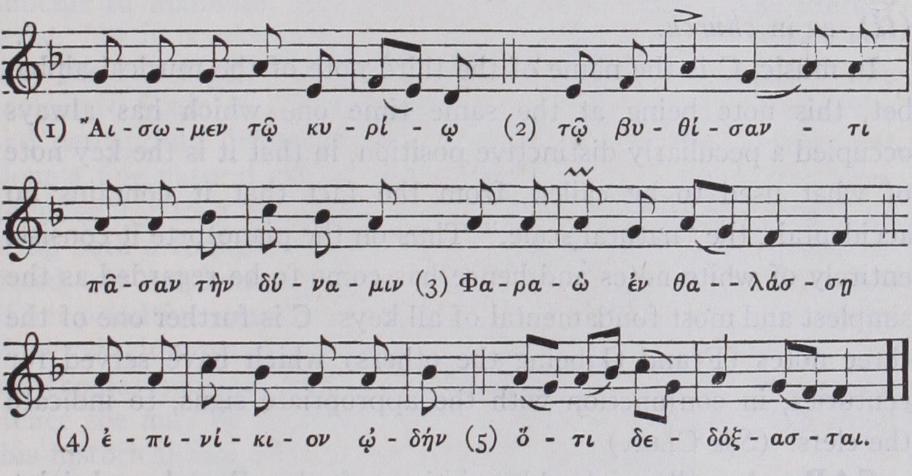

Example of a mediaeval Byzantine hymn (about 1400 A.D.), viz..— First Ode of a Canon from ms. No. 1165, at Trinity College, Cambridge. Mode III. Plagal (Barys or Grave) from f, Finalis f.

Translation. "14t us sing unto the Lord, who sank all the might of Pharaoh in th6 sea, a song of victory, for He hath triumphed gloriously." BIBLIOGRAPHY.-(I) For the Modern or Chrysanthine System: W. Bibliography.-(I) For the Modern or Chrysanthine System: W. Christ and M. Paranikas, Anthologia graeca carminum Christianorum; E. Bourgault-Ducoudray, Etudes sur la musique eccles grecque; J. M. Neale and S. G. Hatherly, Hymns of the Eastern Church with Music; P. Rebours, Traite de Psaltique. (2) Chiefly for the Mediaeval Sys tems: 0. Fleischer, Neumenstudien, T. 3.; Am. Gastoue, Introd. do la Paleographie mus. byzantine; H. J. W. Tillyard, Byzantine Music and Hymnography; E. Wellesz, Byzantinische Musik. (H. J. W. T.)