Caerleon

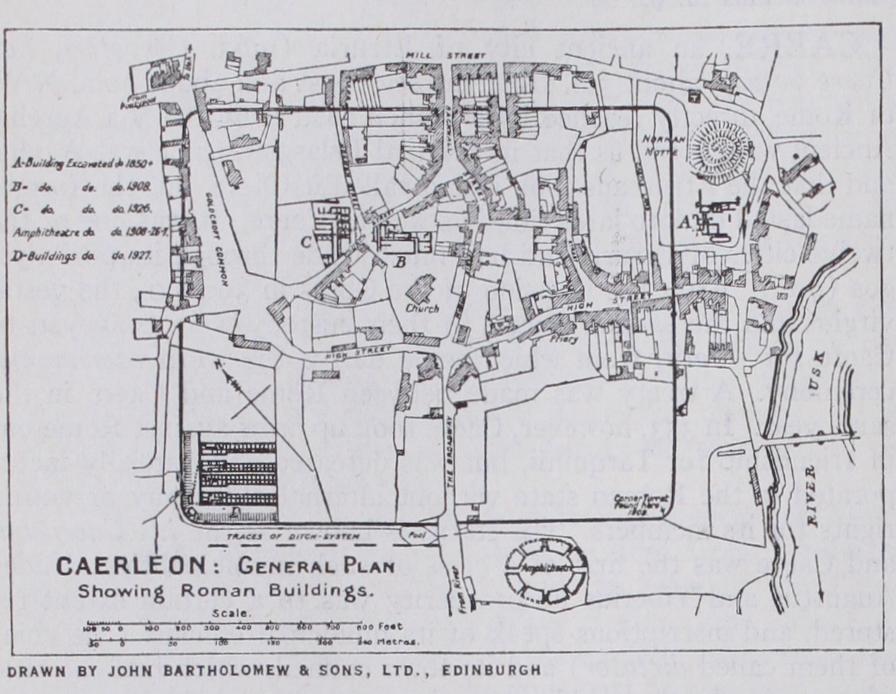

CAERLEON, a country village in the southern parliamentary division of Monmouthshire, England, on the right (west) bank of the Usk, 3 m. N.E. of Newport. Pop. (1931) 2.326. Its claim to notice rests on its importance as the site of the Roman legion ary fortress of Isca (not Isca Silurum), founded and garrisoned by Legio II. Augusta following its campaign against the Silures. This legion had formed the right wing of the expeditionary force of 50,00o men landed in Britain by the emperor Claudius in A.D. 43. According to Tacitus (Annals XII., 32) it first entered South Wales in A.D. 50, and from then on until c. A.D. 75 was engaged in the reduction of the Silures. As will be shown, the fortress was probably founded in the latter year. The choice of the site was no doubt dictated by its command of the coastal approach into South Wales, its general accessibility, and its great natural strength. Visi ble remains of the original works are few. They indicate a rec tangular enclosure with rounded angles, 540 yards long by 450 yards broad, with an internal area of roughly 5o acres.

Recent Excavations.

The systematic exploration of the site was begun by the National Museum of Wales in 1926. The initial defences of the fortress, as excavations have now shown, consisted of a V-shaped ditch, 25 feet wide by 8 feet deep, and a clay bank, 20 feet wide by 8 feet high, with an inner revetment of timber. Pottery sherds recovered from the bank together with coin-finds from the site generally show that the fortress was established in the Flavian period, not improbably immediately after the final defeat of the Silures by Julius Frontinus in c. A.D. 75 (Tacitus, Agricola, 17). At a later date, probably towards the close of the century the outer face of the clay bank was strengthened with an embattled stone wall, 5 feet in basal thickness and still standing in places to a height of 12 feet. The wall was pierced by four symmetrically placed gateways and equipped with an elaborate system of internal look-out turrets situated at regular intervals of 5o yards. In the early 3rd century the turrets appear to have been turned into furnace-chambers. A heavily-metalled roadway (the via sagularis or angularis) skirted the base of the ramparts within. As to the internal lay-out of the fortress, the street-plan of the modern village is evidence that it conformed to type. The fortress was traversed by two streets, the via principalis or "prin cipal way" crossing between the two lateral gateways and to-day vaguely followed by Backhall Street, Museum Street, and the Broadway, and the via quintana, a lesser street whose original line is roughly indicated by modern Norman Street. A third street that with interruptions ran the length of the fortress between the other two gateways is preserved, if irregularly, in modern High Street. The principal buildings were ranged across the space be tween the lateral streets (the principia). They must have included, among others, the praetorium or headquarters building (a large edifice situated in the centre of the space and to-day therefore partly covered by S. Cadoc's Church), the residence of the legion ary commander, and perhaps the granaries. Parts of two of these buildings were excavated in 1908 and 1928, but not enough was exposed to identify them.

Barracks.

The remainder of the space within the fortress, that in front of the principal buildings (the praetentura) and that behind (the retentura), was occupied by the barracks of the soldiers and such other buildings as the hospital, the houses of the tribunes, the prison, stables, and various workshops. Part of what may have been a tribune's house or else the hospital was opened up in 1926, while four barrack-buildings lying immediately within the western angle of the fortress and a long narrow un identified building of probably early 3rd century date backing the north-western rampart were cleared in 1927-8. The barracks consisted as normally of long narrow oblong hutments, each 40 feet wide by 250 feet long, arranged in pairs separated by a nar row alleyway, the buildings of each pair opening on to a common street. Each hutment accommodated a company of 10o men under the command of a centurion. The latter with his assistant non commissioned officers occupied a spacious suite of rooms at one end of the building, while the men were quartered in a row of twelve double cubicles extending down its length. The drainage of these and the other buildings within the defences was ensured by a large underground culvert following the inner edge of the rampart-roadway and probably emptying ultimately into the Usk.

Environs.

The environs of the fortress, apart from the site of the amphitheatre, have not yet been investigated. But it is cer tain that the open fields outside the walls to the south and west contain the foundations of more or less extensive "suburbs." These would include bath-buildings, temples, the "married-quar ters" of, the legionaries, and of course the amphitheatre. In addi tion, there were the tileries and the cemeteries of the legion. The sites of two bath-buildings have been identified, one between the fortress and the Usk to the south-east and the other immediately to the south-west of the amphitheatre. As to the presence of temples, and inscription (Corpus Inscriptionum Latinorum, VII., 95) records the restoration of a temple of Diana in the 3rd cen tury. Exhaustive excavations have laid bare the character and history of the amphitheatre. It was a small oval stone structure of simple type, some 267 feet long by 222 feet broad, with eight entrances. Its seating capacity was about 6,000 persons. It was built in the late 1st century, re-built after a partial collapse in c. A.D. 125, and again re-built after decay in the early 3rd cen tury. Its use seems to have ended with that century. The site of the tileries is not known, but cemeteries have been found to the north-east and north-west of the fortress and across the Usk.

Chronology.

Certain details of the history of the fortress have already been given. On present evidence it would appear to fall into two main phases, the first a period of earthen defences and timber buildings, the second when defences and buildings had been given permanent form in stone. The chronology of these phases seems variable. Thus, while the barrack-blocks and certain at least of the other lesser buildings within the fortress were already of stone as early as c. A.D. 100, the principal build ings, strangely enough, seem to have persisted in timber down to at least 200. There are indications that the occupation of the fortress suddenly diminished in the early 2nd century, a diminu tion probably to be correlated with the known transfer north wards of large detachments of the 2nd Legion for work on Had rian's Wall. The 3rd century saw a renewal of occupation on an intensive scale. Inscriptions (C.I.L. VII., 106-107) datable to this century speak of the reconstruction (? in stone) of the head quarters building (?) and of the re-building of barracks a solo. A sequence of coin-finds extending into the 4th century found on the sites of the two buildings excavated in the principia suggests the presence of at any rate a cadre garrison as late perhaps as A.D. 350; but against this must be set, on the one hand, the con struction about this time of a new coastal fortress of Saxon Shore type at Cardiff 14 miles away (? as a substitute for a now obsolete inland base) and, on the other, the entry in the early 5th century Notitia Dignitatum ascribing the 2nd Legion or part of it to Richborough (Rutupiae) in Kent. Life in the suburbs may have lingered on longer—it is perhaps significant that the Latin name Castra Legionis, whence is derived the Welsh Caerl leon (E. Caerleon), dates from the 6th century—but it can have had no permanent form as at York (Eburacum).

Legends and Traditions.

The common notion that Caer leon was the seat of a Christian bishopric in the 4th century is unproved and improbable. Its later recorded history is scarcely less fanciful. Welsh legend has made the site very famous with tales of Arthur (revived by Tennyson in his Idylls), of Christian martyrs, Aaron and Julius, and of an archbishopric held by St. Dubric and shifted to St. David's in the 6th century. But most of these traditions date from Geoffrey of Monmouth (about 1130-1140), and must not be taken for history. The ruins of Caerleon attracted notice in the 12th and following centuries, and gave plain cause for legend-making. There is better, but still slender, reason for the belief that it was here, and not at Chester, that five kings of the Cymry rowed Edgar in a barge as a sign of his sovereignty (A.D. 973).See Lee, Isca Silurum (1862) and Supplement (i868), a catalogue of the objects in the Caerleon Museum; C.I.L. (1873) VII., 95-136 (Hubner) and Ephemeris Epigraphica (Haverfield) ; Liverpool Com mittee for Research in Wales Report (5908), 53-82 (Evelyn-White) ; Wheeler, Prehistoric and Roman Wales; Archaeologia Cambrensis (1927), 380-384 (Nash-Williams) for a discussion of the name; ib. (1928), 1-32 (Wheeler), preliminary report on the excavation of the amphitheatre.