Calendar

CALENDAR, so called from the Roman Calends or Kalends, a method of distributing time into certain periods adapted to the purposes of civil life, as hours, days, weeks, months, years, etc.

The solar day is distinguished by the daily revolution of the earth and the alternation of light and darkness. The solar year completes the circle of the seasons. The phases of the moon yield the month. The solar day, the solar year, and the lunar month, or lunation, are called the natural divisions of time. The hour, the week, and the civil month are conventional divisions.

Day, Week and Month.

The subdivision of the day (q.v.) into twenty-four parts, or hours combines a natural with a con ventional division. The week, a period of seven days, having no reference whatever to the celestial motions, might have been suggested by the phases of the moon, or by the number of the planets known in ancient times, an origin which is rendered more probable from the names universally given to the different days of which it is composed.The English names of the days are derived from the Saxon. The ancient Saxons had borrowed the week from some Eastern nation, and substituted the names of their own divinities for those of the gods of the East.

Latin English Saxon Dies Solis. Sunday. Sun's day.

Dies Lunae. Monday. Moon's day.

Dies Martis. Tuesday. Tiw's day.

Dies Mercurii. Wednesday. Woden's day.

Dies Jovis. Thursday. Thor's day.

Dies Veneris. Friday. Frigg's day.

Dies Saturni. Saturday. Seterne's day.

Long before the exact length of the year was determined, it must have been perceived that the synodic revolution of the moon is accomplished in about days. Twelve lunations, therefore, form a period of 3 54 days, which differs only by about 11a days from the solar year. From this circumstance has arisen the prac tice of dividing the year into twelve months. But in the course of a few years the accumulated difference between the solar year and twelve lunar months would become considerable, and have the effect of transporting the commencement of the year to a different season. To avoid this inconvenience some peoples have abandoned the moon altogether, and regulate their year by the course of the sun. The month, however, being a convenient period of time, has retained its place in the calendars of all nations, and usually denotes an arbitrary number of days approaching to the twelfth part of a solar year.

Year.—The year is either astronomical or civil. The solar astronomical year is the period of time in which the earth per forms a revolution in its orbit about the sun, or passes from any point of the ecliptic to the same point again; and consists of 365 days 5 hours 48 min. and 46 sec. of mean solar time. The civil year is that which is employed in chronology, and varies among different peoples, both in respect of the season at which it com mences and of its subdivisions. When regard is had to the sun's motion alone, the regulation of the year, and the distribution of the days into months, may be effected without much trouble; but the difficulty is greatly increased when it is sought to reconcile solar and lunar periods, or to make the subdivisions of the year depend on the moon, and at the same time to preserve the cor respondence between the whole year and the seasons.

In the arrangement of the civil year, two objects are sought to be accomplished—first, the equable distribution of the days among twelve months; and secondly, the preservation of the beginning of the year at the same distance from the solstices or equinoxes. Now, as the year consists of 365 days and a fraction, and 365 is a number not divisible by I 2, the months can not all be of the same length and at the same time include all the days of the year. By reason also of the fractional excess of the length of the year above 365 days, the years cannot all contain the same number of days if the epoch of their commencement remains fixed; for the day and the civil year must necessarily be considered as beginning at the same instant ; and therefore the extra hours cannot be in cluded in the year till they have accumulated to a whole day. As soon as this has taken place, an additional day must be given to the year.

The civil calendar of all European countries has been borrowed from that of the Romans. At the time of Julius Caesar, the civil equinox differed from the astronomical by three months, so that the winter months were carried back into autumn and the autumnal into summer.

Caesar abolished the use of the lunar year and the intercalary month, and regulated the civil year entirely by the sun. With the advice and assistance of Sosigenes, he fixed the mean length of the year at 3651 days, and decreed that every fourth year should have 366 days, the other years having each 365. The first Julian year commenced with the 1st of January of the 46th before the birth of Christ, and the 708th from the foundation of the city.

It may be recorded that evidence has now come to light of the existence in earlier days of a calendar based on a standard year starting from noon on our February 2 5th.

For many years it was imagined that Caesar readjusted the year so that the first, third, fifth, seventh, ninth and eleventh months, that is, January, March, May, July, September and November should have each thirty-one days, and the other months thirty, excepting February, which in common years should have only twenty-nine, but every fourth year thirty days. But no ancient or modern authority supports this view, which is a flat contradiction of what Macrobius says in his Saturnalia 1,14,7, statements that are repeated in effect in section 9. Most modern authorities are agreed that much of the suggestion about Augustan activities is unwarranted and that Augustus had noth ing to do with the lengthening of the month bearing his name.

The additional day which occurred every fourth year was given to February, as being the shortest month, and this additional or intercalary day was called bis-sexto calendas.

Although the Julian method of intercalation is perhaps the most convenient that could be adopted, yet, as it supposes the year too long by II minutes 14 seconds, the real error amounts to a day in 128 years. In the course of a few centuries, however, the equinox sensibly retrogrades towards the beginning of the year. In order to restore the equinox to its former place, Pope Gregory XIII. directed ten days to be suppressed in the calendar; and as the error of the Julian intercalation was now found to amount to three days in 400 years, he ordered the intercalations to be omitted on all the centenary years excepting those which are multiples of 400.

According to modern astronomy the mean geocentric motion of the sun in longitude, from the mean equinox during a Julian year of 365.25 days, is 36o° + 27".685. Thus the mean length of the 0 solar year is ° 360 „ X365.25=365.2422 days, or 365 days 5 hours 48 min. 46 sec. Now the Gregorian rule gives 97 inter calations in 400 years; 400 years therefore contain 365X400+97, that is, 146,097 days; and consequently one year contains 365.2425 days, or 365 days 5 hours 49 min. 12 sec. This exceeds the true solar year by 26 seconds, which amount to a day in 3,323 years. It has therefore been proposed to correct the Gregorian rule by making the year 4000 and all its multiples common years. With this correction the rule of intercalation is as follows:— Every year the number of which is divisible by 4 is a leap year, excepting the last year of each century, which is a leap year only when the number of the century is divisible by 4; but 4,000, and its multiples, 8,000, 12,00o, 16,000, etc., are common years. Thus the uniformity of the intercalation, by continuing to depend on the number four, is preserved, and by the last correction the be ginning of the year would not vary more than a day from its present place in two hundred centuries.

The Lunar Year.—The lunar year, consisting of twelve lunar months, contains only 354 days ; its commencement consequently anticipates that of the solar year by eleven days, and passes through the whole circle of the seasons in about 34 lunar years. It being so obviously ill-adapted to the computation of time, almost all nations employ some method of intercalation, by means of which the beginning of the year is retained at nearly the same fixed place in the seasons.

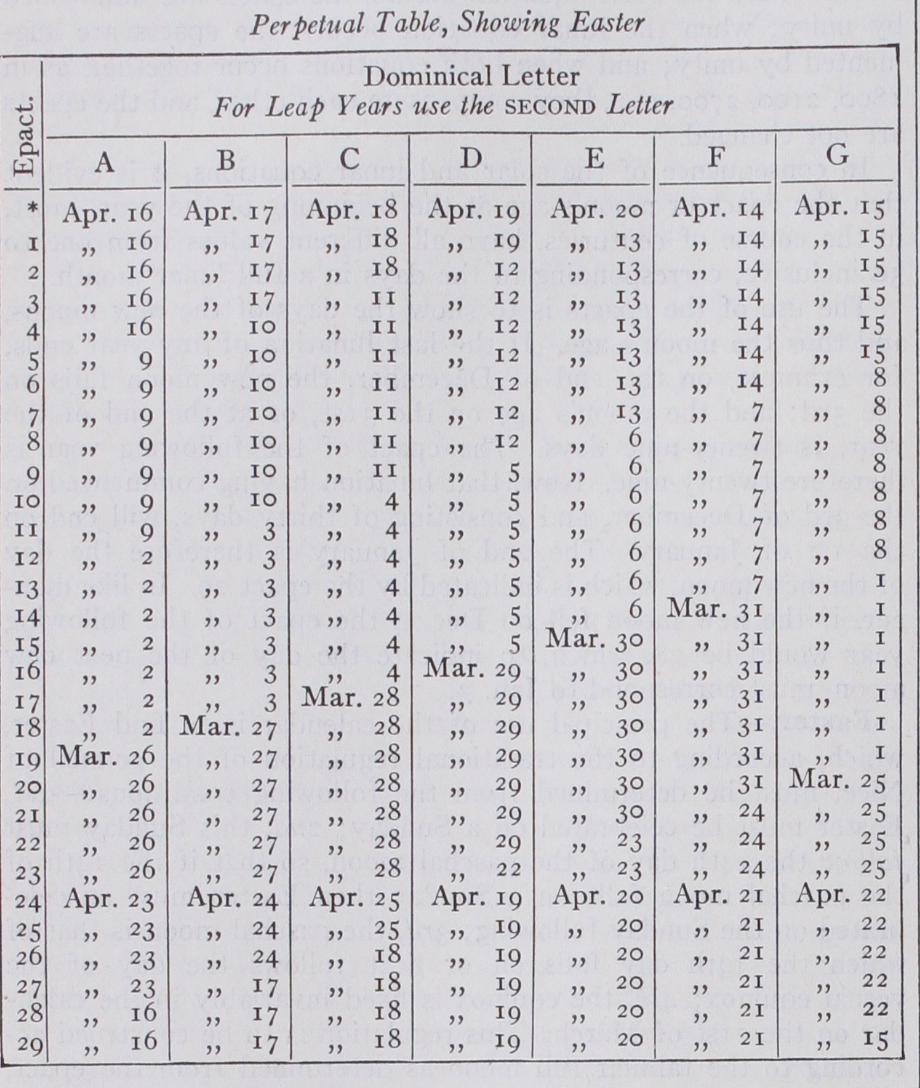

Ecclesiastical Calendar.—The ecclesiastical calendar which is adopted in all the Catholic and most of the Protestant countries of Europe is luni-solar, being regulated partly by the solar, and partly by the lunar year, a circumstance which gives rise to the distinction between the movable and immovable feasts. By the 2nd century of our era, disputes had arisen among the Christians respecting the proper time of celebrating Easter, which governs all the other movable feasts. The Jews celebrated their passover on the 14th day of the first month, that is to say, the lunar month of which the 14th day either falls on, or next follows, the day of the vernal equinox. Most Christian sects agreed that Easter should be celebrated on a Sunday. Others followed the example of the Jews, and adhered to the 14th of the moon; but these, the minority, were accounted heretics, and received the appellation of Quartodecimans. The council of Nicaea, in the year 325, ordained that the celebration of Easter should thenceforth always take place on the Sunday which immediately follows the full moon that happens upon, or next after, the day of the vernal equinox. Should the 14th of the moon, which is regarded as the day of full moon, happen on a Sunday, the celebration of Easter was deferred to the Sunday following, in order to avoid concurrence with the Jews and the above-men tioned heretics. The observance of this rule renders it necessary to reconcile three periods which have no common measure, namely, the week, the lunar month, and the solar year; and as this can only be done approximately, and within certain limits, the determination of Easter is an affair of considerable nicety and complication.

Dominical Letter.

The first problem which the construc tion of the calendar presents is to connect the week with the year, or to find the day of the week corresponding to a given day of any year of the era. As the number of days in the week and the number in the year are prime to one another, two suc cessive years cannot begin with the same day; for if a com mon year begins, for example, with Sunday, the following year will begin with Monday, and if a leap year begins with Sunday, the year following will begin with Tuesday. For the sake of greater generality, the days of the week are denoted by the first seven letters of the alphabet, A, B, C, D, E, F, G, which are placed in the calendar beside the days of the year, so that A stands opposite the first day of January, B opposite the second, and so on to G, which stands opposite the seventh; after which A returns to the eighth, and so on through the 365 days of the year. Now if one of the days of the week, Sunday for example, is represented by E, Monday will be represented by F, Tuesday by G, Wednesday by A, and so on ; and every Sunday through the year will have the same character E, every Monday F, and so with regard to the rest. The letter which denotes Sunday is called the Dominical Letter, or the Sunday Letter; and when the dominical letter of the year is known, the letters which re spectively correspond to the other days of the week become known at the same time.

Solar Cycle.

In the Julian calendar the dominical letters are readily found by means of a short cycle, in which they recur in the same order without interruption. The number of years in the intercalary period being four, and the days of the week being seven, their product is 4 X 7=28; twenty-eight years is therefore a period which includes all the possible combinations of the days of the week with the commencement of the year. This period, the Solar Cycle, or the Cycle of the Sun, restores the first day of the year to the same day of the week. At the end of the cycle the dominical letters return again in the same order on the same days of the month ; hence a table of dominical letters, constructed for twenty-eight years, will serve to show the dominical letter of any given year from the commencement of the era to the Reformation. The cycle, though probably not invented before the time of the council of Nicaea, is regarded as having commenced nine years before the era, so that the year one was the tenth of the solar cycle. To find the year of the cycle, we have therefore the following rule :—Add nine to the date, divide the sum by twenty-eight; the quotient is the number of cycles elapsed, and the remainder is the year of the cycle. Should there be no remainder, the proposed year is the twenty eighth or last of the cycle. In order to make use of the solar cycle in finding the dominical letter, it is necessary to know that the first year of the Christian era began with Saturday. The dominical letter of that year, which was the tenth of the cycle, was consequently B. The following year, or the i i th of the cycle, the letter was A; then G. The fourth year was bissextile, and the dominical letters were F, E; the following year D, and so on. In this manner it is easy to find the dominical letter be longing to each of the twenty-eight years of the cycle. But at the end of a century the order is interrupted in the Gregorian calendar by the secular suppression of the leap year; hence the cycle can only be employed during a century. In the reformed calendar the intercalary period is four hundred years, which number being multiplied by seven, gives two thousand eight hundred years as the interval in which the coincidence is re stored between the days of the year and the days of the week.

Lunar Cycle and Golden Number.

In connecting the lunar month with the solar year, the framers of the ecclesiastical cal endar adopted the lunar cycle, and organized the distribution of months. The lunations are supposed to consist of twenty-nine and thirty days alternately, or the lunar year of 354 days; and in order to make up nineteen solar years, six intercalary months, of thirty days each, are introduced in the course of the cycle, and one of twenty-nine days is added at the end. This gives days, to be distributed among 235 lunar months. But every leap year one day must be added to the lunar month in which the 29th of February is included. Now if leap year happens on the first, second or third year of the period, there will be five leap years in the period, but only four when the first leap year falls on the fourth. In the former case the number of days in the period becomes 6,94o and in the latter 6,939. The mean length of the cycle is therefore days, agreeing exactly with nineteen Julian years.By means of the lunar cycle the new moons of the calendar were indicated before the Reformation. As the cycle restores these phenomena to the same days of the civil month, they will fall on the same days in any two years which occupy the same place in the cycle; consequently a table of the moon's phases for 19 years will serve for any year whatever when we know its number in the cycle. This number is called the Golden Number, either because it was so termed by the Greeks, or because it was usual to mark it with red letters in the calendar. The golden numbers were introduced into the calendar about the year 53o, but disposed as they would have been if they had been inserted at the time of the council of Nicaea. The cycle is supposed to commence with the year in which the new moon falls on the 1st of January, which took place the year preceding the com mencement of our era. Hence, to find the golden number N, for any year x, we have N = (x+ which gives the following 19 rule: Add i to the date, divide the sum by 19; the quotient is the number of cycles elapsed, and the remainder is the Golden Number. When the remainder is o, the proposed year is of course the last or 19th of the cycle. The new moons, determined in this manner, may differ from the astronomical new moons some times as much as two days, because the sum of the solar and lunar inequalities, which are compensated in the whole period, may amount in certain cases to io°, and thereby cause the new moon to arrive on the second day before or after its mean time.

Dionysian Period.

The cycle of the sun brings back the days of the month to the same day of the week; the lunar cycle restores the new moons to the same day of the month ; therefore 28 X 19=J32 years, includes all the variations in respect of the new moons and the dominical letters, and is consequently a period after which the new moons again occur on the same day of the month and the same day of the week. This is called the Dionysian or Great Paschal Period, from its having been employed by Dionysius Exiguus, familiarly styled "Denys the Little," in de termining Easter Sunday. It was, however, first proposed by Victorius of Aquitaine, who had been appointed by Pope Hilary to revise and correct the church calendar. Hence it is also called the Victorian Period. It continued in use till the Gregorian ref ormation.

Cycle of Indiction.

Besides the solar and lunar cycles, there is a third of 15 years, called the cycle of indiction, frequently employed in the computations of chronologists. This period has reference to certain judicial acts which took place at stated epochs under the Greek emperors. Its commencement is referred to the 1st of January of the year 313 of the common era. By extending it backwards, it will be found that the first of the era was the fourth of the cycle of indiction. The number of any year in this cycle will therefore be given by the formula , that 15 r is to say, add 3 to the date, divide the sum by is, and the re mainder is the year of the indiction. When the remainder is o, the proposed year is the fifteenth of the cycle.

Julian Period.

The Julian period, proposed by the cele brated Joseph Scaliger as an universal measure of chronology, is formed by taking the continued product of the three cycles of the sun, of the moon, and of the indiction, and is consequently = 7,98o years. In the course of this long period no two years can be expressed by the same numbers in all the three cycles. Hence, when the number of any proposed year in each of the cycles is known, its number in the Julian period can be determined.

Reformation of the Calendar.

The ancient Church Calen dar was founded on two suppositions, both erroneous, namely, that the year contains 3654 days and that 235 lunations are ex actly equal to 19 solar years. It could not therefore long continue to preserve its correspondence with the seasons, or to indicate the days of the new moons with the same accuracy. Pope Greg ory XIII. issued a brief in the month of March 1582, in which he abolished the use of the ancient calendar, and substituted that which has since been received in almost all Christian countries under the name of the Gregorian Calendar or New Style. The author of the system adopted by Gregory was Aloysius Lilius, or Luigi Lilio Ghiraldi, a learned astronomer and physician of Naples, who died, however, before its introduction ; but the in dividual who most contributed to give the ecclesiastical calendar its present form, and who was charged with all the calculations necessary for its verification, was Clavius, by whom it was com pletely developed and explained in a great folio treatise of 800 pages, published in 1603.In order to restore the beginning of the year to the same place in the seasons that it had occupied at the time of the council of Nicaea, Gregory directed the day following the feast of St. Fran cis, that is to say the 5th of October, to be reckoned the 15th of that month. By this regulation the vernal equinox which then happened on the 11th of March was restored to the 21st. From 1582 to 1700 the difference between the old and new style con tinued to be ten days ; but 1700 being a leap year in the Julian calendar, and a common year in the Gregorian, the difference of the styles during the i8th century was eleven days. The year 180o was also common in the new calendar, and, consequently, the difference in the 19th century was twelve days. From 1900 to 2100 inclusive it is thirteen days.

The restoration of the equinox to its former place in the year and the correction of the intercalary period, were attended with no difficulty; but Lilius had also to adapt the lunar year to the new rule of intercalation. The lunar cycle contained 6,939 days 18 hours, whereas the exact time of 235 lunations, as we have al ready seen, is days 16 hours 31 minutes. The difference, 1 hour 29 minutes, amounts to a day in 3o8 years, so that at the end of this time the new moons occur one day earlier than they are indicated by the golden numbers. Lilius rejected the golden numbers from the calendar, and supplied their place by another set of numbers called Epacts, a term of Greek origin, which, employed in the calendar, signifies the moon's age at the beginning of the year. The common solar year con taining 365 days, and the lunar year only 354 days, the differ ence is eleven; whence, if a new moon fall on the 1st of January in any year, the moon will be eleven days old on the first day of the following year, and twenty-two days on the first of the third year. The numbers eleven and twenty-two are therefore the epacts of those years respectively. Another addition of eleven gives thirty-three for the epact of the fourth year; but in conse quence of the insertion of the intercalary month in each third year of the lunar cycle, this epact is reduced to three. In like manner the epacts of all the following years of the cycle are ob tained by successively adding eleven to the epact of the former year, and rejecting thirty as often as the sum exceeds that num ber. Two equations or corrections must be applied, one depend ing on the error of the Julian year, which is called the solar equa tion ; the other on the error of the lunar cycle, which is called the lunar equation. The solar equation occurs three times in 400 years, namely, in every secular year which is not a leap year; for in this case the omission of the intercalary day causes the new moons to arrive one day later in all the following months, so that the moon's age at the end of the month is one day less than it would have been if the intercalation had been made, and the epacts must accordingly be all diminished by unity. Thus the epacts 11, 22, 3, 14, etc., become 10, 21, 2, 13, etc. On the other hand, when the time, by which the new moons anticipate the lunar cycle, amounts to a whole day, which, as we have seen, it does in 3o8 years, the new moons will arrive one day earlier, and the epacts must consequently be increased by unity. Thus the epacts 11, 22, 3, 14, etc., in consequence of the lunar equation, become 12, 23, 4, 15, etc. In order to preserve the uniformity of the calendar, the epacts are changed only at the commence ment of a century; the correction of the error of the lunar cycle is therefore made at the end of 30o years. In the Gregorian calendar this error is assumed to amount to one day in 3121 years or eight days in 2,500 years, an assumption which requires the line of epacts to be changed seven times successively at the end of each period of 30o years, and once at the end of 400 years; and, from the manner in which the epacts were disposed at the Reformation, it was found most correct to suppose one of the periods of 2,500 years to terminate with the year i800.

The years in which the solar equation occurs, counting from the Reformation, are 1700, 1800, 1900, 2100, 2200, 2300, 2500, etc. Those in which the lunar equation occurs are i 800, 2100, 2400, 2700, 3000, 3300, 3600, 3900, after which, 4300, 460o and so on. When the solar equation occurs, the epacts are diminished by unity; when the lunar equation occurs, the epacts are aug mented by unity; and when both equations occur together, as in 1800, 2100, 2700, etc., they compensate each other, and the epacts are not changed.

In consequence of the solar and lunar equations, it is evident that the epact or moon's age at the beginning of the year, must, in the course of centuries, have all different values from one to 3o inclusive, corresponding to the days in a full lunar month.

The use of the epacts is to show the days of the new moons, and thus the moon's age. If the last lunation of any year ends, for example, on the 2nd of December, the new moon falls on the 3rd; and the moon's age on the 31st, or at the end of the year, is twenty-nine days. The epact of the following year is therefore twenty-nine. Now, that lunation having commenced on the 3rd of December, and consisting of thirty days, will end on the 1st of January. The 2nd of January is therefore the day of the new moon, which is indicated by the epact 29. In like man ner, if the new moon fell on Dec. 4 the epact of the following year would be 28, which, to indicate the day of the next new moon, must correspond to Jan. 3.

Easter.-The

principal use of the calendar is to find Easter, which, according to the traditional regulation of the council of Nice, must be determined from the following conditions :-1st, Easter must be celebrated on a Sunday; 2nd, this Sunday must follow the i4th day of the paschal moon, so that if the 14th of the paschal moon falls on a Sunday then Easter must be cele brated on the Sunday following; 3rd, the paschal moon is that of which the i4th day falls on or next follows the day of the vernal equinox; 4th, the equinox is fixed invariably in the calen dar on the 21st of March. This regulation is to be construed ac cording to the tabular full moon as determined from the epact, and not by the true full moon, which, in general, occurs one or two days earlier.From these conditions it follows that the paschal full moon, or the 24th of the paschal moon, cannot happen before the 21st of March, and that Easter in consequence cannot happen before the 22nd of March. If the 14th of the moon falls on the 21st, the new moon must fall on the 8th; for 21-13=8; and the paschal new moon cannot happen before the 8th ; for suppose the new moon to fall on the 7th, then the full moon would arrive on the loth, or the day before the equinox. The following moon would be the paschal moon. But the fourteenth of this moon falls at the latest on the 18th of April, or 29 days after the 2oth of March; for by reason of the double epact that occurs at the 4th and 5th of April, this lunation has only 29 days. Now, if in this case the i8th of April is Sunday, then Easter must be cele brated on the following Sunday, or the 25th of April. Hence Easter Sunday cannot happen earlier than the 22nd of March, or later than the 25th of April.

The complicated, though highly ingenious method, invented by Lilius, for the determination of Easter and the other movable feasts, is entirely independent of astronomical tables, or indeed of any celestial phenomena whatever; so that all chances of dis agreement arising from the inevitable errors of tables, or the un certainty of observation, are avoided, and Easter determined without the possibility of mistake. But this advantage is only procured by the sacrifice of some accuracy; for the conditions of the problem are not always exactly satisfied, nor can they be always satisfied by any similar method of proceeding. The equinox is fixed on the 21st of March, though the sun enters Aries generally on the 2oth of that month, sometimes even on the 19th. A full moon may therefore arrive after the true equinox, and yet precede the 21st of March. This would not be the paschal moon of the calendar, though it undoubtedly ought to be so if the intention of the council of Nice were rigidly followed. The new moons indicated by the epacts also differ from the astro nomical new moons, and even from the mean new moons, in gen eral by one or two days. In imitation of the Jews, who counted the time of the new moon, not from the moment of the actual phase, but from the time the moon first became visible after the conjunction, the fourteenth day of the moon is regarded as the full moon. But the moon is in opposition generally on the 16th day ; theref ore, when the new moons of the calendar nearly con cur with the true new moons, the full moons are considerably in error. The epacts are also placed so as to indicate the full moons generally one or two days after the true full moons ; but this was done to avoid the chance of concurring with the Jewish passover, which the framers of the calendar seem to have con sidered a greater evil than that of celebrating Easter a week too late.

In 1923 a committee was appointed by the League of Nations to consider the reform of the Calendar and the establishment of a fixed Easter. No evidence was discovered of a wide desire to alter the calendar, but there was much secular support and a certain sympathy from some religious authorities in favour of a fixed Easter. In 1928 a private member's bill was introduced into the British parliament, and duly passed in August (the Easter Act) ; it provided that, from a date to be fixed by an Order in Council, Easter day shall be the first Sunday following the second Saturday in April. This Order in Council may not be made, how ever, until a draft of the order has been approved by parliament— a safeguard intended to ensure uniform action with other countries, and to prevent the taking of any definite step before being assured of the acknowledged support of the religious denominations.

The principal church feasts depending on Easter, and the times of their celebration are as follows:— The Gregorian calendar was introduced into Spain, Portugal and part of Italy the same day as at Rome. In France it was received in the same year in the month of December, and by the Catholic states of Germany the year following. In the Protestant states of Germany the Julian calendar was adhered to till the year 1700, when it was decreed by the diet of Regensburg that the new style and the Gregorian correction of the intercalation should be adopted. Instead, however, of employing the golden numbers and epacts for the determination of Easter and the movable feasts, it was resolved that the equinox and the paschal moon should be found by astronomical computation from the Rudolphine tables. But this method was abandoned in i774 at the instance of Frederick II., king of Prussia. In Denmark and Sweden the reformed calendar was received about the same time as in the Protestant states of Germany. Russia adhered to the Julian reckoning, until it was superseded by the Soviet Govern ment, which introduced the Gregorian reckoning.

In Great Britain the Calendar (New Style) Act 175o was passed for the adoption of the new style in all public and legal transactions. The difference of the two styles, which then amounted to eleven days, was removed by ordering the day f ol lowing the and of September of the year 1752 to be accounted the 14th of ' that month ; and in order to preserve uniformity in future, the Gregorian rule of intercalation respecting the secular years was adopted. At the same time, the commencement of the legal year was changed from the 25th of March to the 1st of January. In Scotland, January 1st was adopted for New Year's Day from I 600, according to an act of the privy council in De cember 1599. This fact is of importance with reference to the date of legal deeds executed in Scotland between that period and 1751, when the change was effected in England. With respect to the movable feasts, Easter is determined by the rule laid down by the council of Nice; but instead of employing the new moons and epacts, the golden numbers are prefixed to the days of the full moons. In those years in which the line of epacts is changed in the Gregorian calendar, the golden numbers are removed to differ ent days, and of course a new table is required whenever the solar or lunar equation occurs. The golden numbers have been placed so that Easter may fall on the same day as in the Gregorian calendar. The calendar of the Church of England is therefore from century to century the same in form as the old Roman calendar, excepting that the golden numbers indicate the full moons instead of the new moons. The Orthodox Church in Greece has adopted a modified Gregorian calendar, with a 90o year cycle. The Orthodox Church in Greece has also adopted the Gregorian system presumably in this form. Easter is computed by the actual, not the simplified ecclesiastical moon. The meridian for calculations is that of Jerusalem.

BIBLIOGRAPHY.-The principal works on the calendar are the followBibliography.-The principal works on the calendar are the follow- ing:—Clavius, Romani Calendarii a Gregorio XIII. P.M. restituti Explicatio (Rome, 1603) ; L'Art de verifier les dates; Lalande, Astron omie, tome ii.; Traite de la sphere et du calendrier, par M. Revard (Paris, 1816) ; Delambre, Traite de l'astronomie theorique et pratique, tome iii. ; Histoire de l'astronomie moderne; Methodus technica brevis, perfacilis, ac perpetua construendi Calendarium Ecclesiasticum, Stylo tam novo quam vetere, pro cunctis Christianis Europae populis, etc., auctore Paulo Tittel (Gottingen, 1816) ; Formole analitiche pel calcolo della Pasqua, e correzione di quello di Gauss, con critiche osservazioni su quanto ha scritto del calendario it Delambri, di Lodovico Ciccolini (Rome, 1817) ; E. H. Lindo, Jewish Calendar for Sixty-four Years (1838) ; W. S. B. Woolhouse, Measures, Weights and Moneys of all Nations (1869) ; R. G. Schram, Kalendariographische and Chronolog ische Tafeln (Leipzig, 1908), Encyclopaedia of Religion and Ethics, vol. iii., 191o, art. Calendar, and articles below. (X.) The calendar of the modern civilized world is a system of time-reckoning which consists of units or divisions and sub divisions which have a strictly limited duration: years, months, days, hours, minutes, and seconds. To define a certain point or space in the lapse of time these units are simply numbered. They serve not only for the indication and reckoning of time but also for its measurement. Consequently units of the same order ought always to have the same length, but here natural causes and tradition create certain exceptions such as months of 31, 3o, 29 and 28 days respectively, and, in the lunisolar calendar, years of alternately 12 and 13 months. Primitive man clings always to the concrete. In his experience certain natural phenomena constantly recur, e.g., the sun and the new moon, and certain phenomena recur in the same order, e.g., snow, the sprouting of the leaves, the ripening of certain fruits, and the falling of the leaves, etc. By reference to such concrete phenomena he is able to indicate a certain time. Time indications of primitive man are not dura tional like the unit of any system of time-reckoning, but indefinite.

Again, the phenomena referred to are often of unequal or indeterminate duration ; they overlap or leave gaps, and cannot be numerically grouped together. Consequently we have to deal with a time-reckoning by time-indications only, or briefly, a dis continuous time-reckoning. A definite and constantly-recurring phenomenon, e.g., a certain day, a certain month, a certain year, is indicated by referring to a certain event or natural phenomenon connected with it as, for instance, the day of the waning of the moon, the month in which the leaves fall, the year of the cattle disease, etc. It is possible to count time by reckoning a single phenomenon, recurring constantly within a certain unit, which has not yet been conceived as such. The child who has seen ten snows or ten harvests is ten years old. Nine new moons ap pear bef ore the woman bears her child. This mode of counting time may be called the pars-pro-toto method. Presuming that the indication of concrete phenomena following one another in the regular succession of Nature has preceded the abstract numer ical indication of time, the origin of time-reckoning is to be found, not in any system, however simple, but in the time-indica tions referring to concrete phenomena and in the pars-pro-toto method of counting time referring to these concrete phenomena.

Celestial phenomena are of outstanding importance. The units of time-reckoning depend on the motions of the heavenly bodies, and the more intimately these enter into the life of man, the more important they are for the calendar. The (solar) day of 24 hours is determined by the rotation of the earth on its axis. The year is the period of a revolution of the earth about the sun. The varying height of the sun and duration of its appearance are ultimately the causes of the seasonal variations of the climate and the life of Nature. By the term "months," the lunar or moon-month is understood, unless expressly stated otherwise. Our months have nothing to do with the moon but are simply subdivisions of the solar year, the length of which comes near that of a lunar month. The lunar month is the interval between two consecutive new moons, and comprises slightly more than 294 days.

Primitive man knows the stars and notes their appearances. It can be observed that some constellations appear in the heavens in the winter, others in the summer. The sun seems to move more slowly than the stars owing to the motion of the earth, and in the course of a year the sun runs through the zodiac back wards. The stars gain every day 3 min. 56 secs. on the sun, i.e., a particular star culminates every day that much earlier than the sun. Primitive man rises and goes to bed with the sun. At dawn he notices the stars that are shining in the east and are soon to vanish before the light of the sun. In the same way he observes at evening, before he goes to rest, the stars on the western horizon which soon afterwards set there. The star of which he is just able to catch a glimpse in the east in the morning twilight, will stand a little higher next morning, and it will rise earlier every morning until after about half a year its rising will take place in the evening twilight. The first visible appearance of a star in the morning twilight is termed its heliacal rising, and the last visible setting of a star in the evening twilight is called its heliacal set ting. The observation of the stars provides a means of determin ing the time from quite regular phenomena, whereas the variations of the seasons in different years may be considerable.

The Day.—The notion of the day of 24 hours, comprising a day and a night, is a late development, so late indeed that most languages lack a proper word for it. Some primitive peoples use such expressions as "light and darkness," "sun-darkness" to de scribe it. But this is rare. The days are counted according to the pars-pro-toto method in "suns," "nights," "sleeps," "dawns" (Homer) ; whoever has slept six nights on the way has under taken a six days' journey. The counting in nights was especially favoured by the old Teutonic peoples (cf. the expressions "fort night," "sennight"). For the indication of a point of time within the day, reference to the course of the sun is very common, and this indication can be given by a gesture. More rarely the posi tion or the length of the shadow is referred to, and still more rarely a staff is used as a sum-dial. In Iceland and the northern parts of Scandinavia the time of the day was determined by mountain peaks or stone heaps above which the sun stood at a certain time of the day. The names of the divisions of the day are derived from natural phenomena, e.g., day-break, twilight, sun-rise, morning, noon, etc., and from the common daily occupa tions. Examples of these are the Homeric description of evening as "the time when the oxen are unyoked," and the Irish im buaracli (morning), "at the yoking of the oxen." Many primitive peoples have elaborate series of expressions of this kind. The night is the time of complete darkness and rest, and time indi cations are therefore scanty. The cock-crow sometimes serves this purpose and, more rarely, the stars are used by peoples who have studied them to determine the lapse of the night, because the position of the stars in the night-sky change every day. These indications do not imply a strictly limited duration as our "hours" do. To indicate a definite time-limit, some activity, the duration of which is known, is referred to, e.g., "the time in which one can cook a handful of vegetables," i.e., an hour, "the frying of a locust," i.e., a moment. Very often duration of time is indicated by reference to the time needed to traverse a well-known piece of road.

The Seasons.—The seasons are sometimes used to determine time within the year, but every seasonal occurrence, e.g., the sow ing, is used thus, and as these have a short duration, they are better suited to indicate time and much more widely used for this purpose. Thus in the classical examples in Hesiod, the cry of the migrating cranes shows the time of ploughing and sowing ; when the snail climbs up the plants there should be no more digging in the vineyards ; when the thistle blossoms summer has come ; the sea can be navigated when the fig-tree sprouts, etc. Similar time indications are still used by peasants. Among primitive peoples they are common, and not only among the agricultural ones. The main seasons differ according to the zones. In the tropics there are dry and rainy seasons, sometimes two of each ; the trade winds and the monsoons and the intervening calms. Although the seasons recur more regularly in the tropics and the sub-tropical regions than in northern climates, they are of varying length, and there are greater and smaller seasons and seasonal points, which overlap. Consequently their number is varying and indefinite. We may, e.g., speak of the year as consisting of winter and sum mer or of spring, summer, harvest and winter. The old Teutons are said to have had only three seasons : winter, spring, and summer. The climatic conditions of the country are of paramount importance. The seasons are seldom adapted for true calendrical purposes, as only with some violence can they be systematized into periods of a definite number of days as the early Scandi navians did with the winter and summer.

The Year.

A cycle of seasons make up a year, and while all peoples have an idea of the year in the sense that the same cycle of seasons always recurs in a certain order, they seldom con sciously unite the different seasons into a year. The notion of the year is a comparatively late and gradual development acquired by means of selection, regulation and systemization of the seasons. Some peoples reckon in half-years—two seasons—with out joining them together, as in East Africa where there are two rainy seasons, and in the East Indian Archipelago, where the south-west and the north-east monsoons each blow for about half a year. Some peoples count one dry and one rainy season without combining them into a year. An incomplete year consisting of about ten months is found especially among some agricultural peoples, but is in reality the vegetation year, from the commence ment of agricultural work to its end, when the harvest is housed; the vacant period is simply passed over. Such reckonings are known to be made in north-east Asia, the East Indian Archipelago and Central Africa. If the vacant period were added to this cycle, the natural year would be attained, but its length is in definite and may vary according to the accidental variations of the climate. A calendrical year is attained only by the aid of the stars or the months. For the counting of years, the pars-pro-toto method is employed. The Hottentots reckon the age of their cattle and sheep by the calving and lambing periods. The Algon quin and the old Scandinavians counted by winters, the fellahs of Palestina and the Inca people by harvests, etc.Primitive peoples ara primarily concerned with the age of a man in relation to his fellows, that is, whether he be older or younger than another, and from this the counting in generations is evolved. Years are not numbered but designated by reference to some well-known event which took place in a certain year, e.g., a plague, cattle disease, war, migration, unusual snowfall, etc. Long lists of such designations of years are quoted from the Herero and some North American Indians. The same method was employed in Babylonia and in pre-Mohammedan Arabia. Higher civilized peoples refer to their chiefs or kings and the years of their reign. If the highest authority is changed annually, the years are designated by their names : thus, in Rome, the year was known by the name of the consul and in Greece by that of the archon. This method is unwieldy, for a long series of names must be kept in mind in correct order.

The Stars.

Time indications by seasons are inexact because the phenomena to which they are related are fluctuating. Obser vation of the stars provides a means of indicating time within the year with greater precision. Most primitive peoples know the stars well, and some extremely well, e.g., the South American Indians, the Polynesians and Melanesians. Hesiod and many classical authors indicate time by the rising and setting of cer tain stars : the vines should be pruned before the evening rising of Arcturus ; the morning setting of the Pleiades is the time of sowing and of the autumn storms. Counting by the stars, particu larly by the Pleiades, is still practised by certain primitive peoples. The appearance of certain stars is connected with seasonal phe nomena and used for determining agricultural occupations. Fi nally, a true notion of the year is formed by a few peoples when the period between a certain appearance of a star or constellation (principally the Pleiades) and its next appearance of the same kind, e.g., the heliacal rising, is noticed. The inhabitants of the Marquesas and some South American Indians call the year and the Pleiades by the same name. In this manner, by observing the heliacal rising of Sirius, the old Egyptians established the solar year, and from them it was adopted by Julius Caesar.

The Moon.

The course of the moon forms a shorter unit which steps in between day and year. The shorter period of time defined by it is easily kept in mind and noted at a glance. It has in itself nothing to do with the natural phases conditioned by the course of the sun. Time-reckoning according to the moon is by its nature continuous and strictly limited. The month is by its nature a definite and limited unit of time. One moon follows another with a brief interruption of only one or two days in which the moon is invisible. The phases of the moon represent a gradual waxing and waning, a continuous development. The principle of continuous time-reckoning is suggested by the moon. The days of the month are originally not counted but designated with reference to the shape of the moon and its position in the sky. The new moon and the full moon have a special prominence and are often hailed with rejoicing and feasting. Then the cres cent of the waning moon is added. Many peoples distinguish the three phases of the waxing, the full and the waning moon; then further phases and the absence of the moon, "when it has gone to sleep," are added. The Polynesians and Micronesians have developed a system by which every day of the month has a name taken from the shape or the position of the moon. Other peoples, e.g., the Masai, the Hindus, etc., count the days of the light and the dark halves of the moon. The Greeks counted in decades after the three principal phases, but there are also traces of a division of the month into two parts. A division into four parts is but rarely found.

The Month.

The months are seldom counted, and then prin cipally in regard to the months of pregnancy; but a month is designated by a natural phenomenon or seasonal occupation oc curring in it, e.g., the blackberry month, sowing month, lambing month, etc. This naming was originally accidental. Sharp dis tinctions were not made, indeed were not possible. There was much overlapping, but from this material, by a kind of natural selection, a series of month-names came into being covering the course of the natural year. A number of such series have been found in all parts of the world except South America and Aus tralia. A year of 13 months is reckoned by quite as many peoples as reckon 12 months.

Inter- or Extra-calation.

Here a fundamental difficulty ap pears, for the solar year has 365+ days; 12 months make 354 days, i.e., Io days too little, 13 months 384 days, i.e., 19 days too much. So long as the month-names are accidental, or only some of the months are named and the two or three months not asso ciated with definite occupations are neglected, the difficulty is passed over. But once a fixed series of months has arisen they soon cease to coincide with the natural phenomena and occupa tions after which they are named. If the series has 12 months, a month will come earlier than the natural phenomenon after which it is named. If the series has 13 months it will soon come after this phenomenon is over. The Dakota often had heated debates as to the existing month and the Pawnees sometimes became in extricably involved in their reckoning. The obvious remedy is to correct the reckoning after the occurrence of the natural phe nomenon. In a 12-month series, for instance, the harvest month which came before the corn was ripe, is repeated ; the first har vest month is then said to have been "lost" or "forgotten." In the 13-month series the month which came after the natural phenomenon is simply left out, and the following month in the series is reckoned. The means resorted to in the former case was the intercalation of a month and in the latter the extracalation of a month to restore the months to their relative position in the seasons, i.e., the solar year, indicated by their names. Thus came into existence the lunisolar year which follows both the sun and the moon, and consequently must have alternately 12 and 13 months. A still more exact means of detecting the deviation of the months and correcting it was attained by naming some or all of the months after the appearances of certain stars as, for in stance, is the practice in north-west America, Polynesia and Mel anesia. In Babylonia, before the middle of the third millennium B.C., the list of months had been fixed and a certain month had been singled out as the intercalary month. (From about 200o B.C. it was one of the two months Adarru or Ululu.) The lunisolar year was regulated by empirical intercalation, which continued down to the Persian times. From Babylonia the Greeks took over the lunisolar year, but in the 7th century B.c. introduced a cyclical intercalation, the octaeteris, thus setting the problem of the scien tific regulation of the calendar.The natural year, being an ever-recurring cycle, has no proper new year, i.e., a point from which the year commences; the be ginning of the year or of the list of month-names varies greatly therefore. But the agricultural year has a definite commencement and end. This end of the agricultural occupations is often cele brated by festivals. It forms the turning point of the year; a new period is entered upon. The European calendrical new year has its origin in the term at which the Roman Consul, after whom the year was named, entered upon his office.

Solstices and Equinoxes.

While the stars were often used for more accurately defining the time within the year, certain points in the course of the sun may be referred to, namely, the solstices and equinoxes (q.v.). This is, however, a more com plicated observation which requires a fixed standing point and cer tain landmarks touched by the sun in its travel from north to south and inversely. In this manner the Eskimos, the Indians of Arizona, the Amazulu, etc., observe the most northern and south ern points reached by the sun, its "houses" or "turning points." They were also known to Homer and Hesiod. The observation of the equinoxes is still more difficult ; for this purpose the Incas had erected towers as artificial marks at Cuzco. Certain gifted and advanced peoples, the Eskimos, the Northern Scandinavians, the Polynesians and Melanesians, have made still more refined obser vations of the course of the sun, but on the whole even the simplest observations of this nature, viz., those of the solstices, play no important part in primitive time-reckoning.

The

Market-week.—There is a wholly artificial period of fairly frequent occurrence among peoples who have sufficiently advanced in civilization to have a regular trade. This is the market-week, or the fixed period of days in which a market is held. It varies in length and lasts three days among the Muysca in Bogota, four among many West African tribes, five in Central America, the East Indian Archipelago and old Assyria, six among a tribe in Togo, eight among the ancient Romans (the nundinae), and ten among the Inca people. On the market day, especially in Africa, work is of ten forbidden, certain taboos are imposed, and religious ceremonies performed. The hypothesis has therefore been advanced that the Israelitish Sabbath was by origin a market day, although the prohibition of work has been extended also to its original purpose of commerce.

Methods of Reckoning.

Finally many peoples use a tally or other device for counting days, moons, and years, and where a more refined science of time-reckoning is evolved it is in the hands of a special class, particularly the priests, who preserve this knowledge and regulate the calendar. Hence the close connection between the religious system and the calendar, for the celebration of the festivals and ceremonies at the right times as indicated by the calendar is the chief duty of the priests, who gathered great knowledge of times and seasons, of the holy days and the work days, of the links between man and the sun, the moon, and the stars. These and the seasons and the cycle of Nature are the material from which by long, hard thought, by patient observa tion, by ever subtler and more accurate calculation, modern sys tems of time-reckoning have been developed.See Martin P. Nilsson, Primitive Time-Reckoning (1920).