California

CALIFORNIA, popularly known as the "Golden State," is one of the Pacific coast group of the United States of America. Physically it is one of the most remarkable, economically one of the most independent, and in history and social life one of the most interesting of the Union. It is bounded on the north by Oregon, east by Nevada and Arizona, from which last it is sepa rated by the Colorado river, and south by the Mexican territory of Lower California, and west by the Pacific ocean. The extreme limits of California extend from 114° to 124° 29' W. and from 32° 3o' to 42° N. The length of its medial line north to south is about 78om., its breadth varies from 1 so to 350m., and its total area is 158,297 sq.m., of which 2,645 are water surface. The coast-line is more than i,000m. long. In size California ranks second among the States of the Union. California was given the name "Golden State" because of its early and continued produc tion of enormous quantities of gold.

Physiography.—The physiography of the State is simple; its main features are few and bold; a mountain fringe along the ocean, another mountain system along the east border, between them—closed in at both ends by their junction—a splendid valley of imperial extent, and outside all this a great area of bar ren, arid lands, belonging partly to the great basin and partly to the open basin region. Along the Pacific, and some 20-40m. in width, runs the mass of the Coast range, made up of numerous indistinct chains—most of which have localized individual names —that are broken down into innumerable ridges and spurs, and small valleys drained by short streams of rapid fall. The range is cut by numerous fault lines, some of which betray evidence of recent activity; it is probable that movements along these faults cause the earthquake tremors to which the region is subject, all of which seem to be tectonic. The altitudes of the Coast range vary from about 2,000 to 8,000f t. ; in the neighbourhood of San Francisco bay the culminating peaks are about 4,000f t. in height (Mt. Diablo, 3,856ft.; Mt. St. Helena, 4,343ft.), and to the north and south the elevation of the range increases. In the east part of the State is the magnificent Sierra Nevada, a great block of the earth's crust, faulted along its eastern side and tilted up so as to have a gentle back slope to the west and a steep fault escarpment facing east, the finest mountain system of the United States. The sierra proper, from Lassen, peak to Tehachapi pass in Kern county, is about 430m. long (from Mt. Shasta in Siskiyou county to Mt. San Jacinto in Riverside county, more than 600 miles). Ear higher and grander than the Coast range, the sierra is much less complicated, being indeed essentially one chain of great simplicity of structure. Precipitous gorges of canyons, often from 2,000 to 5,000f t. in depth, become a more and more marked feature of the range as one proceeds northward; over great por tions of it they average not more than tom. apart. The eastern slope is very steep, due to a great fault which threw the rocks of the great basin region abruptly downward several thousand feet. Few passes cross the chain. Between 36° 20' and 38° the lowest gap of any kind is above 9,000f t., and the average height of those actually used is probably not less than Ii,000 feet. The Kear sarge, most used of all, is still higher. Some 4o peaks are cata logued between 5,00o and 8,000ft., and there are I 1 above 14, 000. The highest portion of the system is between the parallels of 36° 3o' and 37° 3o'; here the peaks range from 13,000f t. up ward, Mt. Whitney, 14,5oift., being the highest summit of the United States, excluding Alaska.

Of the mountain scenery the granite pinnacles and domes of the highest sierra opposite Owens lake, where there is a drop eastward into the valley of about io,000ft. in Iom.; the snowy volcanic cone of Mt. Shasta, rising 1 o,000f t. above the adjacent plains; and the lovely valleys of the Coast range, and the south fork of the Kings river—all these have their charms ; but most beautiful of all is the unique scenery of the Yosemite valley (q.v.). Much of the ruggedness and beauty of the mountains is due to the erosive action of many alpine glaciers that once existed on the higher summits, and which have left behind their evidences in valleys and amphitheatres with towering walls, polished rock expanses, glacial lakes and meadows, and tumbling waterfalls. Remnants of these glaciers are still to be seen—as notably on Mt. Shasta—though shrunk to small dimensions. The canyons are largely the work of rivers. The finest of the lakes is Tahoe, 6, 2 2 5 f t. above the sea, lying between the true sierras and the basin ranges, with peaks on several sides rising 4,000-5,000f t. above it. Clear lake, in the Coast range, is another beautiful sheet of water. Volcanic action has likewise left abundant traces, especially in the northern half of the range, whereas the evidences of glacial action are most perfect (though not most abundant) in the south. Lava covers most of the northern half of the range, and there are many craters and ash-cones, some recent and of perfect form. Of these the most remarkable is Mt. Shasta. In Owens valley is a fine group of extinct or dormant volcanoes. Among the other indications of great geological disturbances on the Pacific coast may also be mentioned the earthquakes to which California like the rest of the coast is subject. They occur in all seasons, scores of tremors being recorded every year by the Weather Bureau; but they are of slight importance, and even of these the number affecting any particular locality is small. In T812 great destruction was wrought by an earthquake that affected all the southern part of California; in 1868 the region about San Francisco was violently disturbed; in 1872 the whole sierra and the State of Nevada were shaken; in 1906' San Francisco (q.v.) was largely destroyed by a shock (and ensuing fire) that caused great damage elsewhere in the State; and in 1925 Santa Barbara was severely shaken. North of 40° N. lat. the Coast range and sierra system unite, forming an extremely rough country. The eastern half of this area is very dry and barren, lying between precipitous, although not very lofty, ranges; the western half is magnificently timbered, and toward the coast excessively wet. Between 35° and 36° N. lat. the sierra, at its southern end, turns westward towards the coast as the Tehachapi range. The valley is thus closed to the north and south, and is surrounded by a moun tain wall, which is broken down in but a single place, the gap behind the Golden Gate at San Francisco. Through this passes the entire drainage of the interior. The length of the valley is about 45om., its breadth averages about 4om. if the lower foothills be included, so that the entire area is about 18,000 square miles. From the mouth of the Sacramento to Redding, at the northern head of the valley, the rise is 5 5 2 f t. in 192m., and from the mouth of the San Joaquin southward to Kern lake it is 282ft. in 26o miles.

Two river systems drain this central basin—the San Joaquin, whose valley comprises more than three-fifths of the entire basin, and the Sacramento, whose valley comprises the remainder. The eastward flanks of the Coast range are very scantily forested, and they furnish not a single stream permanent enough to reach either the Sacramento or San Joaquin throughout the dry season. On the eastern side of both rivers are various important tribu taries, fed by the more abundant rains and melting snows of the western flank of the sierra. The Feather is the most important tributary emptying into the Sacramento river. A striking feature of the Sacramento system is that for Zoom. N. of the Feather it does not receive a single tributary of any importance. Another peculiar and very general feature of the drainage system of the State is the presence of numerous so-called river "sinks," where the waters disappear, either directly by evaporation or (as in Death valley) after flowing for a time beneath the surface. These "sinks" are therefore not the true sinks of limestone regions. Some of the mountain lakes show by the terraces about them that the water stood during the glacial period much higher than it does now. Tulare lake, which has practically disappeared, was formerly a shallow body of water, some 25 miles broad, that received the drainage of the southern Sierra, a flow that is believed to have shrunk greatly since 185o. The drainage of Lassen, Siskiyou and Modoc counties has no outlet .to the sea and is collected in a number of alkaline lakes.

Finally along the sea below Point Conception are fertile coastal plains of considerable extent, separated from the interior deserts by various mountain ranges from 5,000 to 7,000ft. high, and with peaks much higher (San Bernardino, 11,600; San Jacinto, 10,800; San Antonio, 10,140). Unlike the northern sierra, the ranges of southern California are broken down in a number of places. It is over these passes—Soledad, 2,822ft., Cajon, 2,631ft.; San Gorgonio, 2,56oft.—that the railways cross to the coast. That part of California which lies to the south and east of the Coast range and the sierra comprises an area of fully 50,000 sq.m. and belongs to the basin range region. For the most part it is excessively dry and barren. The Mohave desert—embracing parts of Kern, Los Angeles and San Bernardino, as also a large part of San Diego, Imperial and Riverside counties—belongs to the great basin, while a narrow strip along the Colorado river is in the open basin region. They have no drainage to the sea, save fitfully for slight areas through the Colorado river. In San Diego, Imperial and Riverside counties a number of creeks or so-called rivers, with beds that are normally dry, flow centrally towards the desert of Salton sink or sea; this is the lowest part of a large area that is depressed below level of the sea—at Salton 248.7ft. and 276ft. at the lowest point. In 190o the Colorado river (q.v.) was tapped south of the Mexican boundary for water wherewith to irrigate land in the Imperial valley along the Southern Pacific railway, south of Salton sea. The river enlarged the canal, and finding a steeper gradient than that to its mouth, was diverted into the Colorado desert, flooding Salton sink, and when the break in this river was closed for the second time, in Feb. 1907, a lake more than 400 sq.m. in area was left. The region to the east of the sierra, between the crest of that range and the Nevada boundary, is very mountainous. Near Owens lake the scenery is extremely grand. The valley here is very narrow, and on either side the mountains rise from 7,000 to 1 o,000f t. above the lake and river. Still farther to the east some 4om. from the lake is Death valley —the name a reminder of the fate of a party of "forty-niners" who perished here, by thirst or by starvation and exposure. Death valley, some 5om. long and, on an average, 2o-25m. broad from the crests of the enclosing mountain ranges (or 5-1om. at their base), constitutes an independent drainage basin. It is 276ft. below sea-level, and altogether is one of the most remarkable physical features of California. The mountains about it are high and bare and brilliant with varied colours. The Amargosa river, entering the valley from Nevada, disappears in the salty basin. Enormous quantities of borax, already exploited, and of nitrate of soda, are known to be present in the surrounding country, the borax an almost pure borate of lime in Tertiary lake sediments. California has the highest land and the lowest land of the United States, and the greatest variety of temperature and rainfall.

Climate.—The climate is very different from that of the Atlantic coast ; and indeed very different from that of any part of the country save that bordering California. In the first place, the climate of the entire Pacific coast is milder and more uniform in temperature than that of the States in corresponding latitude east of the mountains. Thus we have to go north as far as Sitka in 57° N. lat. to find the same mean yearly temperature as that of Halifax, Nova Scotia, in latitude 39'. And going south along the coast, we find the mean temperature of San Diego 6° or 7° less than that of Vicksburg, Miss., or Charleston, S.C. In the second place, the means of winter and summer are much nearer the mean of the year in California than in the east. This condition of things is not so marked as one goes inward from the coast; yet everywhere, save in the high mountains, the winters are com paratively mild. In the third place, the division of the year into two seasons—a wet one and a dry one—marks this portion of the Pacific coast in the most decided manner, being truly character istic neither of Lower California nor of the greater part of Oregon, though more so of Nevada and Arizona. And finally, except on the coast, the disagreeableness of the heat of summer is greatly lessened by the dryness of the air and the consequent rapidity of evaporation.

Along both the Coast range and the sierra considerable rainfall is certain, although, owing to the slight snow accumulations of the former, its streams are decidedly variable. A heavy rain-belt, with a normal fall of more than 4oin., covers all the northern half of the sierra and the north-west counties; shading off from this is the region of io-2oin. fall, which covers all the rest of the State save Inyo, Kern and San Bernardino counties, Imperial county and the eastern portion of Riverside county; the precipitation of this belt is from o to io inches. In the mountains the precipita tion increases with the altitude; above 6,000 or 7,0ooft. it is almost wholly in the form of snow; and this snow, melting in summer, is of immense importance to the State, supplying water at one time for placer-mining and later for irrigation. The north-west counties are extremely wet; many localities here have normal rain falls of 6o-7oin. and even higher annually. Along the entire Pacific coast, but particularly north of San Francisco, there is a night fog from May to September. Below San Francisco the precipitation decreases along the coast, until at San Diego it is only about 1 o inches. The extreme heat of the south-east is tem pered by the extremely low humidity characteristic of the great basin. Many places in northern, southern, central, mountain and southern coastal California normally have more than 20o clear days in a year ; and many in the mountains and in the south, even on the coast, have more than 25o.

The Colorado desert (together with the lower Gila valley of Arizona) is the hottest part of the United States. Along the line of the Southern Pacific the yearly extreme is frequently from 124° to 129° F (i.e., in the shade, which is almost, if not quite, the greatest heat ever actually recorded in any part of the world). At the other extreme temperatures of —2o° to —36° are recorded yearly near Lake Tahoe. The normal annual means of the coldest localities of the State are from 37° to 44° F; the monthly means from 2o° to 65° F. The normal annual means on Indio, Mammoth Tanks, Salton and Volcano springs are from 73•9° to 78.4° F; the monthly means from 52.8° to 101.3° (frequently 95° to 98°). Another weather factor is the winds, which are extremely regular in their movements. There are brisk diurnal sea-breezes, and sea sonal trades and counter-trades. Along the coast an on-shore breeze blows every summer day; in the evening it is replaced by a night fog, and the cooler air draws down the mountain sides in opposition to its movement during the day.

There is the widest and most startling variety of local climates. There are points in southern California where one may actually look from sea to desert and from snow to orange groves. Distance from the ocean, situation with reference to the mountain ranges, and altitude are all important determinants of these climatic dif ferences; but of these the last seems to be most important. Death valley surpasses for combined heat and aridity any meteorological stations on earth where regular observations are taken, 'although for extremes of heat it is exceeded by places in the Colorado desert.

Soil.—Sand and loams in great variety, grading from mere sand to adobe, make up the soils of the State. The plains of the north-east counties are volcanic, and those of the south-east, sandy. It is impossible to say with accuracy what part of the State may properly be classed as tillable. Much land is too rough, too elevated or too arid ever to be made agriculturally available; but irrigation, and the work of the State and national agricultural bureau in introducing new plants and promoting scientific farm ing, have accomplished much that once seemed impossible. Irriga tion was introduced in southern California before 1780, but its use was desultory and its spread slow till after 185o. In 1920, 4, 219,o4oac. were irrigated, an increase of 181% since 1900. More than half of this total was in San Joaquin valley. California has the greatest area of irrigated land of any State in the Union, and offers the most complete utilization of resources. In the south artesian wells, and in the great valley the rivers of the sierra slope, are the main sources of water-supply. On nearly all lands irrigated some crops will grow in ordinary seasons without irrigation, but it is this that makes possible selection of crops; practically indispensable for all field and orchard culture in the south, save for a few moist coastal areas, it everywhere increases the yield of all crops and is practised generally all over the State.

Government.--In

the matter of Constitutions California has been conservative, having had only two. The first was framed by a convention at Monterey in 1849, and ratified by the people and proclaimed by the U.S. military governor in the same year. The present Constitution, framed by a convention in came into full effect in 1880, and was subsequently amended. It was the work of the Labour Party, passed at a time of high discontent, and goes at great length into the details of govern ment, as was demanded by the state of public opinion. The qualifications required for the suffrage are in no way different from those common throughout the Union, except that by a con stitutional amendment of 1894 it is necessary for a voter to be able to read the State Constitution and write his name. As com pared with the earlier Constitution it showed many radical advances toward popular control, the power of the legislature being everywhere curtailed. Power was taken from the Legis lature by specific inhibition in 31 subjects previously within its power. "Lobbying" was made a felony; provisions were inserted to tax and control common carriers and great corpora tions, and to regulate telegraph, telephone, storage and wharfage charges. The Constitution may be amended by a two-thirds vote of all the members elected to each house of the legislature, fol lowed by ratification by a majority vote of the qualified electors voting on the proposition. Since 1911 amendments may be sub mitted directly to the people by means of the "initiative." A Constitutional Convention may be called by the legislature when two-thirds of all members of the legislature deem it necessary, provided the question is approved by a majority vote at the next general election. The work of the convention must be submitted to the people for approval or rejection.

The executive officers elected by the people of the State every four years are a governor, a lieutenant-governor, a secretary of State, a controller, a treasurer, a State board of equalization, a surveyor-general, an attorney-general and a superintendent of public instruction. Besides these executive and administrative officers, there are more than 5o boards, commissions, officers, etc., appointed by the governor, with or without the consent of the Senate. The legislature consists of two houses—a Senate of 4o members elected for four-year terms and an Assembly of 8o members elected for two-year terms. Regular sessions of the legislature are held in the odd-numbered years and are divided into two parts, a recess of not less than 3o days separating the two sessions. In the second part no bill may be introduced into either house without the consent of three-fourths of its members, and no member may introduce more than two bills.

The judicial powers of the State are confined to a supreme court, three district courts of appeal, superior courts, and justice of the peace and police courts. The supreme court consists of a chief justice and six associate justices elected by the people of the State for a term of 12 years. Regular sessions of the court are held in Sacramento, San Francisco and Los Angeles. The district courts of appeal have six judges each for the first and second district, and three judges for the third district; but in every case three judges constitute a separate court. Judges are elected by the votes of their respective districts for a term of 12 years. Each county has a superior court with one or more judges (Los Angeles county has 28) elected by the people for a term of six years. There is at least one justice of the peace for each township, elected for a period of four years. The Constitution of 1879 made provision for expediting trials and decisions. Notable was the innovation that agreement by three-fourths of a jury should be sufficient in civil cases and that a jury might be waived in minor criminal cases, a provision which was based on experience under the Mexican law.

The State is divided into 58 counties, and it is here that the chief administrative functions of local government take place. Municipalities are divided into six classes according to population. There is no uniform type of city government—the mayor-council, the commission and the city manager systems are all in common usage. Notable among the measures granting a greater popular control of the Government are the primary law of 1909 and the constitutional amendments of 1911 establishing the initiative and referendum, the recall (including the recall of judges), and the adoption of the short ballot.

Population.

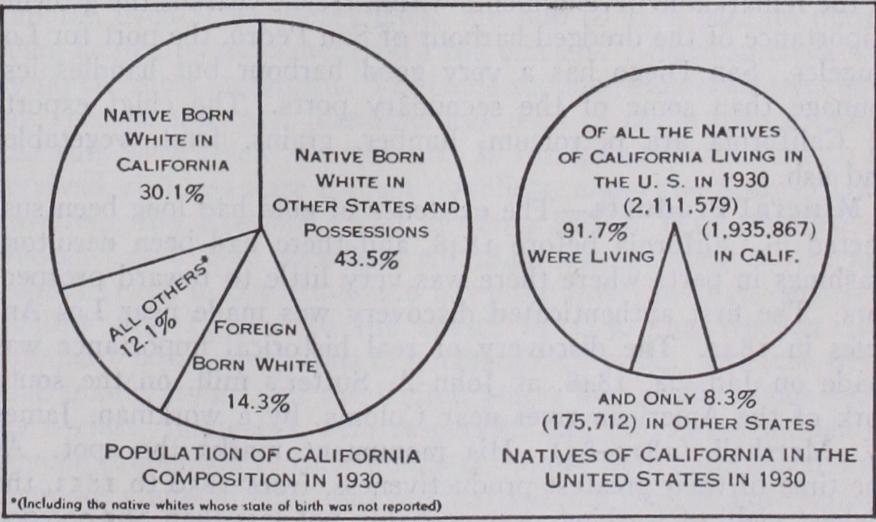

The population of California in successive decades from 1850 to 1920 was as follows: 92,597 in 994 in 186o; 567,247 in 1870; 864,694 in 188o; 1,213,398 in 1890; in 1900; 2,377,549 in 1910; 3,426,861 in 1920 or an increase of 44.1% for the last decade. According to the census figures in 1920 the State ranked in population eighth among the States of the Union. The population in 193o was The density of population in 192o was 22 per sq.m. ; in 193o it was 36.5. The urban population (in places of 2,500 or more) in 1920 was 2,331,729, an increase during the decade from 61.8% to 68% of the total population. Of the cities, 47 had a population of 1o,o00 or more in 1930, and of this number three had more than 200,000 inhabitants; Los Angeles (1,238,048), San Francisco (634,394) , and Oakland (284,063) . Of the entire population in 1920, 3,264711 were white, 38,763 negro, 17,360 Indian, 28,812 Chinese and 71.952 Japanese. During the decade 1910-20 the Chinese population decreased 7,436, while the Japanese increased 30,596. The State's total foreign-born population in 1920 was 681,662. Thirty-three countries contributed over 1,000 residents each, the leading ones being Italy, 88,502; Mexico, 86,61o; Ger many, 67,180; Canada, 59,562; England, 58,662; Ireland, 45,308; and Sweden, 31,925.

Finance.

Until 1910 the chief source of State and local rev enue was a levy upon property. In that year the system was changed by a constitutional amendment in accordance with which public utility corporations were made exempt from local property taxes but subject to a State tax on their gross receipts. Other sources of State revenue were an inheritance tax, corporation license fees, a gasolene (petrol) tax, motor vehicle licenses, a compensation insurance tax, the sale of bonds, and income from the school fund and lands. Another amendment ratified June authorized the restoration of the exempted company properties to local assessment rolls. In August a retail sales tax was adopted. The chief disbursements of the State government are for general expenses, highways, and educa tion; appropriations for the last of these accounted for 48.85%, of the State's receipts for the year 1933-34. In 1932 revenues totaled $118,897,000, of which $89,963,000 came from taxes; the gross debt was $147,179,000. Tax receipts for the fiscal year ending June 3o, 1934 were $124,462,883.86.

Education.

The educational system of California is one of the best in the country. It provides a complete system of free instruction from the kindergarten through the State uni versity, and in the elementary and secondary schools even text-books and supplies are furnished without cost to individ ual pupils. At the head of the public school system are the State superintendent of public instruction and the State board of education, a body consisting of seven members appointed by the governor. All schools are governed by a board of educa tion. Outside the cities the school districts are governed by boards of trustees of three mem bers, and, in the case of union districts, of five members. There was a compulsory attendance law passed in 1874 which has since been amended so as to require all children between the ages of eight and 16 to attend for the entire school year un less graduated from a four-year high school or exempted by the proper school authorities. Sec ondary schools are closely affili ated with, and inspected by, the State university. All schools are generously supported, salaries are usually good, and pension funds in all cities are authorized by State laws.The school population sons between the ages of five and seventeen years inclusive) was in 1932. Public school enrolment for the same year was 1,123,550 or 94.1% of all persons who were of school age; and in addition to these, 65,83o were enrolled in private and parochial schools. In the enrolment in public schools was 1,412,239, of whom 63,743 were in dergartens, 767,752 in the first eight grades, and 580,744 in high schools and junior colleges. The average number of days attended per pupil enrolled during the year 1932 was 153.9 as compared with 142 in 191o. Total tures for the year amounted to $149,812,000, or a per capita expenditure, based upon population between five and seventeen inclusive, of which placed California second highest among the states.

Of the higher educational institutions of the State the Uni versity of California (q.v.), with the two main parts at Berkeley and Los Angeles, is by far the most important. In 1935 there were also seven State teachers' colleges located at Chico, Arcata, Fresno, San Diego, San Francisco, San Jose and Santa Barbara. There is also a State polytechnic school at San Luis Obispo. Among the endowed and denominational universities and colleges, Stanford University, near Palo Alto, is the greatest, with a plant valued above $15,971,000 and productive funds of about thirty-two million dollars. Its library is reported to contain over 600,000 volumes. Another university of great importance is the University of California at Los Angeles.

Agriculture.—The rapid development of the spread of irri gation and of intensive cultivation, and the increase of small farms during the last few decades have made California an agri cultural region and a great fruit-producing area. Staple products have changed with increasing knowledge of climatic conditions, of life-zones and of the fitness of crops. Irrigation has shown that with water, arid and barren plains, veritable deserts, may be made to bloom with immense wealth of semi-tropical fruits. The aver age size of farms in 1850, when the large Mexican grants were almost the only farms, was 4,466ac. ; in 1910 it was 316.7ac., and in 1935 only 202.4 acres. In 1920 there were 9,365,667ac. in farms, of which 11,878,339ac. were improved land. The total acreage had risen to 7,995 in 1935. The value per acre in creased from $47.16 in 1910 to $114 in 1925 but had fallen by to $76.40. In 1920 the total value of all farm property was this value had fallen to by but rose again to $3,419,470,764 in 1935. There were 4,746,632 acres under irrigation in 1929, placing California above all other states in this regard. The total area of farm lands on January 1, was acres, of which 18,719,778 acres were oper ated by full or part owners, 4,915,403 acres by managers, and 6,802,814 acres by tenants.

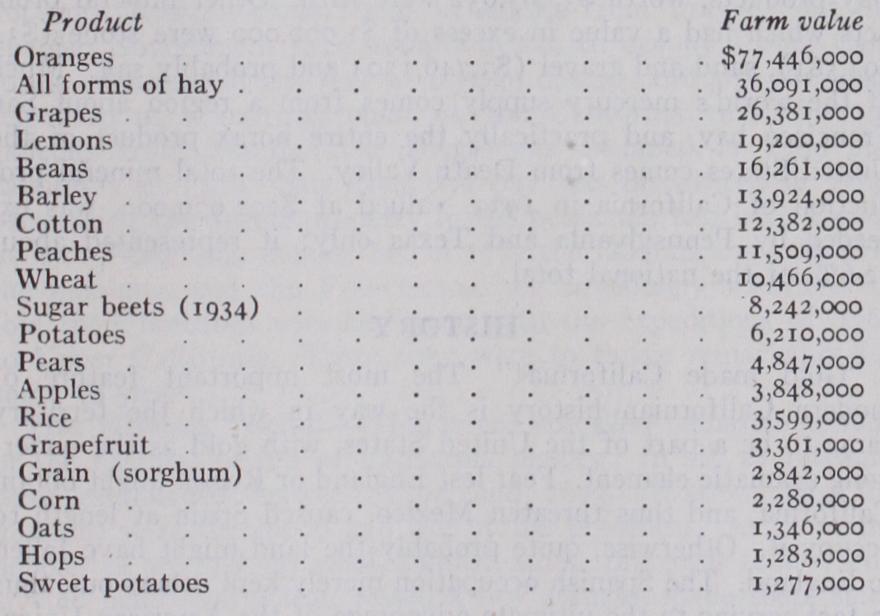

The table below lists twenty of the chief crops of the State with the estimated values of their respective crops for 1935 (in one instance for Other crops normally of outstanding importance, for which com parable figures are not available, are prunes, walnuts, lettuce, cantaloupes, asparagus, and tomatoes.

The live stock industry was introduced by the Franciscans and flourished throughout the period before the region was annexed to the United States. In the development of California since that time the live stock industry has become subordinate but has not wholly lost its economic significance. In 1934 the gross income of the State from live stock and live stock prod ucts (chiefly market milk, butter, ice cream, evaporated and condensed milk, and market cream) was $145,000,000. On Janu ary I, 1935, according to the agricultural census, there were in the State 2,131,799 head of cattle with a value of 191,977 horses, with a value of $15,404,546; 2,724,242 sheep and lambs of all ages, with a value of $13,621,210; and 489,291 swine, with a value of $3,229,321.

Horticultural products, as shown in the table, are the principal products of the soil. The modern orange industry practically began with the introduction into southern California in 1873 of two seedless orange trees from Brazil ; from their stock have been developed, by budding, millions of trees bearing a seedless fruit which now holds high rank in the American market. Shipments continue all the year round. Southern California by no means monopolizes the warm-zone fruits. Oranges, lemons and walnuts come chiefly from that section, but citrus fruits grow also in the sierra foothills of the great interior valley. Almonds and peaches, pears, plums, cherries and apricots, come mainly from the north. Over one-half of the prune crop comes from Santa Clara county, and the bulk of the raisin output from Fresno county. Olives thrive as far north as the head of the great valley. Vines were first introduced by the Franciscans in 1771 from Spain, and until 186o "Mission" grapes were practically the only stock in Cali fornia. Afterwards many hundreds of European varieties were introduced with great success.

Fisheries.—Fishing is not an industry of major importance in California, but it is one of interest because of its relative magni tude there as compared with other States. Thus, in according to the Statistical Abstract, California ranked second only to Massachusetts in the value of her fishery products. In quantity she headed the list, with a yield for the year amounting to 706,899 pounds at a total value of $7,094,300. The corre sponding figures for Massachusetts were 373,67o pounds and $9,507,000 respectively. The fish of chief importance are the albacore, the pilchard or sardine, and the yellow fin tuna. Other species of great commercial value are the barracuda, the cod, the California halibut, the salmon, the striped tuna, the blue fin tuna, and the yellow tail. In the canning of tuna fish the state has no rival, and since 1926 she has exceeded Maine in the packing of sardines.

Manufactures.

Previous to 186o almost everything used in the State was imported from the East or from Europe. For many years manufacturing was handicapped by the State's lack of coal, but the opening of the petroleum fields and the increased use of the mountain streams to create electric power, obviated the difficulty. California had attained the rank of eighth among the States and first west of the Mississippi in the value of products manufactured in 1929. In that year there were 11,893 industrial establishments, giving employment to 289,550 wage-earners, and having an output worth By these figures had dropped to 8,429 establishments, 191,861 workers, and $1,488,181,000 respectively. Most important was the refining of petroleum, in which field California stood pre-eminent, with a product in valued at $212,939,324. Canning and preserv ing came next in order, with a product for that year of $146, And in this business too the State was without equal. Other industries with products valued above $35,000,000 in were: rolling mills, foundries, and machine shops, printing and publishing, $84,037,200; meat packing, $82,643.144; baking motor vehicles, $55,882,558; dairy manu factures, $45,371,750; liquors, $42,492,805; lumber and planing mill products, $36,581,577 ; clothing manufactures, $35,086,939. In the motion picture industry, centred at Hollywood, but not covered by the census of manufactures, California leads the nation.

In lumber production the State ranked fifth in 1933, when the cut for California was 785,000,000 board feet. The chief varie ties were redwood, yellow pine, fir, sugar pine, cedar and spruce. In 1934 there were 19 national forest reserves within the State, with a combined area of 19,175,640 and a stand of commercial timber estimated at 102,251,000,000 board feet. There are also three national parks, five national monuments, one State park and several small State forest reserves within the State.

Transcontinental Commerce.

The transportation facilities in California increased rapidly after the completion of the first continental line in 1869 by the connection of the Central Pacific and Union Pacific lines. The New Orleans line of the Southern Pacific was opened in Jan. 1883 ; the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe owns the lines built to San Diego in 1885, and to San Francisco bay in 190o. Other railways of importance are the San Pedro and Salt Lake (the Union Pacific) and the Western Pacific. The total steam railway mileage, exclusive of switches and terminal roads, in the State on December 31, 1933 was 8,272 miles. This was supplemented by about 3,00o miles of electric railways. After 1919 there was a rapid improvement in highways. The state high way system on December 31, 1933 had a total mileage of of which all but 4,054 were surfaced. An epochal event in the development of highway communication was the opening on Nov. 12, 1936 of the 84 mile bridge from San Francisco across the harbour to Oakland. The use of motor vehicles for passen ger and freight transportation in California, as elsewhere, has increased rapidly within the last two decades. The total motor vehicle registration for 1930 was 2,041,356, which represented an increase of almost 25o% over the figure for 1920. Registra tion fell off during the early years of the depression but had nearly regained the level of 1929 by the end of 1934, when the figure stood at 2,006,255.There is now frequent freight and passenger service from San Francisco and Los Angeles (San Pedro) with Hawaii, Australia, and eastern Asia, as well as with American ports, both Atlantic and Pacific. Water-borne imports and exports for 1933 showed 1,205,913 cargo tons imported and 5,854,000 tons exported. San Francisco imported 751,550 tons as compared with 443,835 tons for Los Angeles; in the export trade Los Angeles had 3,067,277 cargo tons as compared with 1,889,575 for San Francisco. One of the remarkable developments within recent years is the growing importance of the dredged harbour of San Pedro, the port for Los Angeles. San Diego has a very good harbour but handles less tonnage than some of the secondary ports. The chief exports of California are petroleum, lumber, grains, fruit, vegetables and fish.

Mineral Products.

The existence of gold had long been sus pected in California before 1848, and there had been desultory washings in parts where there was very little to reward prospec tors. The first authenticated discovery was made near Los An geles in 1842. The discovery of real historical importance was made on Jan. 24, 1848, at John A. Sutter's mill, on the south fork of the American river near Coloma, by a workman, James W. Marshall (1810-85) . His monument marks the spot. At the time of their greatest productiveness, from 185o to 1853, the highest yield of washings was probably not less than $65,000,000 a year. From the record of actual exports and a comparison of the most authoritative estimates of total production, it may be said that from 1848 to 1856 the yield was almost certainly not less than $450,000,000, and that about 1870 the $1,000,000, 000 mark had been passed. Placer-mining was of chief importance in the early years, but after the richer deposits had been exploited the machine-worked quartz mines came into prominence. In more than half of the gold output was from such mines. Quartz veins are often as good at a depth of 3,000ft. as at surface. A remarkable feature of mining since 190o is gold "dredging." Thousands of acres of land have been thus recently treated.In 1933 the stimulus of higher prices for the metal resulted in a marked expansion of gold mining in California. The number of placer mines rose from 828 in 1932 to 993 (an increase of 20%) in 1933; the number of lode mines mounted from 718 to 797 (an increase of 1 i%). Output from the former class of mines swelled by 30,849 fine ounces (or 13%) and that of the latter class by 13,563 fine ounces (or 4%). The total produc tion of the State from all mines advanced from 569,166.99 fine ounces, valued at $11,765,726, to 613,578.85 fine ounces, worth $12,683,801. About 77% of the placer gold produced during the year 1933 was mined by 16 companies working 25 dredges. These companies recovered 201,710 fine ounces from 55,331,000 cubic yards of gravel—an average yield of .0036 ounces per cubic yard as against the .0039 ounces per cubic yard recovered by dredges in the preceding year.

Petroleum and products associated with it have an annual value far in excess of the historically important gold. The production of crude petroleum grew rapidly after 1895, its out put soaring from 4,325,000 barrels in 1900 to 262,876,000 bar rels in 1923. This high figure sagged to 224,11 7,000 barrels in 1926 but more than recovered by 1929, when it stood at 292, barrels. The depression, however, inevitably drove it down once more so that in 1933 only 172,010,000 barrels were produced. The well value of oil in 1920 was $3.07 ; in 1926 it was $1.88; in 1929, $1.27; in 1933, just $o.67, making the total value of California's output for that year about $115,246,700. Oil is found from north to south over some 60o miles, but especially in the southern part of the State. The largest produc tion in 1933 came from the Los Angeles district, where the wells of Long Beach, Santa Fe Springs, and Huntington Beach were especially active ; next in order was the district of the San Joaquin Valley, of which the most heavily producing wells were in the Kettleman Hills and the Midway-Maricopa regions. In the coastal district, the Ventura Avenue region was the most impor tant producer.

Natural gasolene was the State's second most valuable mineral product in 1933, its estimated value for that year being about $22,820,000. Third in rank was natural gas, the output of which in 1933 had a value at the wells of around $16,690,000. Cement came fourth on the list with a value of about $10,500,000; and clay products, worth $3,863,632 were fifth. Other mineral prod ucts which had a value in excess of $1,000,00o were stone ($3, sand and gravel ($3,746,13o) and probably salt. Much of the world's mercury supply comes from a region about San Francisco bay, and practically the entire borax product of the United States comes from Death Valley. The total mineral pro duction of California in 1933, valued at $292,979,000, was ex ceeded by Pennsylvania and Texas only ; it represented about 12.6% of the national total.

"Gold made California!" The most important feature of modern Californian history is the way in which the territory came to be a part of the United States, with gold as the under lying dramatic element. Fear lest England or Russia might obtain California, and thus threaten Mexico, caused Spain at length to occupy it. Otherwise, quite probably the land might have fallen to England. The Spanish occupation merely kept others out, thus in fact serving to the ultimate advantage of the American Union, which would not have been strong enough to take over California much prior to the time when it actually did so. If the Spanish settlers had discovered California's gold, the destiny of the prov ince would have been different from what it proved to be; in that event it might have become a Spanish-American republic, or England might have acquired it. The discovery of gold was postponed, however, until the Americans were already pouring into the province. Thereafter the rush of American settlers put the stamp of certainty on the connection with the United States.

Exploration and Early Settlement.

The name "Califor nia" was taken from Ordonez de Montalvo's story, Las Sergas de Esplandic n (Madrid, 151o), of black Amazons ruling an island of this name "at the right hand of the Indies . . . very close to that part of the Terrestrial Paradise." The name was given to the southern part of Lower California probably in but at any rate before 1542. By extension it was applied in the plural to the entire Pacific coast north from Cape San Lucas. Neces sarily the name had for a long time no definite geographic meaning. The lower Colorado river was discovered in 154o, but the explorers did not penetrate California; in Juan Rodriguez Cabrillo and his successor, Bartolome Ferrelo, explored probably the entire coast to a point just north of the present boundary; in 1579 Sir Francis Drake repaired his ships in Drake's bay, and named the land New Albion; Spanish galleons en route from the Philippines to Acapulco usually sighted the coast, and certainly did so in the voyages of 1584 and 1595; and in a famous voyage of 16o2–o3 Sebastian Vizcaino carefully explored the coast, and discovered the Bay of Monterey. There was apparently no increase of knowledge thereafter for 15o years. Most of this time California was generally supposed to be an island or a group of islands. Jesuit missionaries entered Lower California as early as 1697, and maintained themselves there until expelled in 1768 by order of Charles III. of Spain; but not until Russian explorations in Alaska from 1745-65 did the Spanish Government take definite action to occupy Upper Cali fornia. Because of the fear of foreign danger, and also the long felt need of a refitting point on the California coast for the galleons from Manila, San Diego was occupied in 1769 and Monterey in 177o. San Francisco bay was discovered in 1769. Meanwhile the Jesuit property in the peninsula had been turned over to Franciscan monks, but in 1772 the Dominicans took over the missions, and the Franciscans not unwillingly withdrew to join their brethren who had gone with the expeditions of 1769 to Upper California. There they were to thrive remarkably for some 5o years.

The Mission Period.

This is the so-called "mission period" or the pastoral period of California history. In all, 21 missions were established between 1769 and 1823. Economically the missions were the blood and life of the provinces. At them the neophytes worked up wool, tanned hides, prepared tallow, cul tivated hemp and wheat, raised a few oranges, made soap, some iron and leather articles, mission furniture, and a very little wine and olive oil. The hides and tallow yielded by the great herds of cattle at the missions were the support of foreign trade, and did much toward paying the expenses of the government. As for the intellectual development of the neophytes the mission system accomplished nothing; save the care of their souls they received no instruction, they were virtually slaves, and were trained into a fatal dependence, so that once coercion was removed they relapsed at once into barbarism. The missions, however, were only one phase of Spanish institutions in California. The govern ment of the province was in the hands of a military officer stationed at Monterey. There were also several other military establishments and civilian towns in the province, as well as a few private ranches. The political upheavals in Spain and Mexico following 1808 made little stir in this far-off province. When revolution broke out in Mexico (181i), California remained loyal to Spain. In 182o the Spanish Constitution was duly sworn to in California, and in 1822 allegiance was given to Mexico. Under the Mexican Federal Constitution of 1824 Upper California, first alone (it was made a distinct province in 1804) and then with Lower California, received representation in the Mexican congress.

Political Unrest.

The following years before American occu pation may be divided into two periods. From about 1840 to 1848 foreign relations are the centre of interest. From 1824 to 184o there is a complicated and not uninteresting move ment of local politics and a preparation for the future—the missions fall, Republicanism grows, the sentiment of local patri otism becomes a political force, there is a succession of sectional controversies and personal struggles among provincial chiefs, an increase of foreign commerce, of foreign immigration, and of foreign influence. The Franciscans were mostly Spaniards in blood and in sympathies. They viewed with displeasure and fore boding the fall of Iturbide's empire and the creation of the republic. After 1821 secularization of the missions was the burn ing question in California politics. Active and thorough seculari zation of the missions did not begin until 1834; by 1835 it was consummated at 16 missions out of 21, and by 184o at all. In 1831 the mission question led to a rising against the reactionary clerical rule of Governor Manuel Victoria. He was driven out of the province. This was the first of the opera bouffe wars. The causes underlying them were serious enough. In the first place, there was a growing dissatisfaction with Mexican rule, which accomplished nothing tangible for good in California, although its plans were as excellent as could be asked had there been peace and means to realize them. In the second place, there was growing jealousy between northern towns and southern towns, northern families and southern families. In 1831 Governor Victoria was deposed; in 1836 Governor Mariano Chico was frightened out of the province; in 1836 Governor Nicolas Gutierrez and in 1844-45 Governor Manuel Micheltorena were driven out of office. The leading natives headed this last rising. There was talk of independence, but sectional and personal jealousies could not be overcome.

Foreign Influence.

By this time foreign influence was in creasing. Foreign commerce, which was contrary to all Spanish laws, was active by the beginning of the 19th century. It was greatly stimulated during the Spanish-American revolutions, for, as the Californian authorities practically ignored the law, smug gling was unnecessary. In the early '4os some three-fourths of the imports, even at Monterey itself, are said to have paid no duties, being landed by agreement with the officials. American trade was by far the most important. The trade supplied almost all the cloth ing, merchandise and manufactures used in the province; hides and furs were given in exchange. If foreign trade was not to be received, still less were foreign travellers, under the' Spanish laws. However, the Russians came in 18o5, and in 1812 founded on Bodega bay a post they held till 1841, whence they traded and hunted (even in San Francisco bay) for furs. In 1826 American hunters first crossed to the coast; in 183o the Hudson Bay Company began operations in northern California. The true over land immigration from the United States began only about 1840. As a class, foreigners were respected, and they were influential beyond proportion to their numbers. Many were naturalized, held generous grants of land, and had married into Californian families, not excluding the most select and influential. Most prominent of foreigners in the interior was John A. Sutter (1803-8o), who held a grant of 11 square leagues around the present site of Sacramento, whereon he built a fort. Though Sutter himself was Swiss, his establishment became a centre of American influence. His position as a Mexican official, and the location of his fortified post on the border, made him of great importance in the years preceding and immediately following American occupation. Ameri cans were hospitably received and very well treated by the Government and the people. There was, however, some jealousy of the ease with which they secured land grants, and an entirely just dislike of "bad" Americans. Many of the later comers wanted to make California a second Texas. As early as 18o5 (at the time of James Monroe's negotiations for Florida), there are traces of Spain's fear of American ambitions, even in this far-away province. Spain's fears passed on to Mexico, the Rus sians being feared only less than Americans. An offer was made by President Jackson in 1835 to buy the northern part of California, including San Francisco bay, but was refused. From 1836 on, foreign interference was much talked about. Americans supposed that Great Britain wished to exchange Mexican bonds for California ; France also was thought to be watching for an opening for gratifying supposed ambitions; and all parties saw that, even without overt act by the United States, the progress of American settlement seemed likely to gain the province.In 1842 Commodore T. A. C. Jones (1789-1858) of the U.S. navy, believing that war had broken out between his country and Mexico, and that a British force was about to seize California, raised the American flag over Monterey (Oct. 21), but finding that he had acted on misinformation, he lowered the flag next day with due ceremony and warm apology. In California this incident served to open up agreeable personal relations and social courte sies, but it did not tend to clarify the diplomatic atmosphere. By 1845 there was certainly an agreement in opinion among all American residents (then not 700 in number) as regards the future of the country. The American consul at Monterey, Thomas O. Larkin (1802-58), was instructed, in 1845, to work for the secession of California from Mexico, without overt aid from the United States, but with their good will and sympathy. He very soon gained from leading officers assurances of such a movement before 1848. At the same time American naval officers were instructed to occupy the ports in case of war with Mexico, but first and last to work for the good will of the natives.

In 1845 Captain J. C. Fremont (q.v.), while engaged in a Government surveying expedition, aroused the apprehensions of the Californian authorities by suspicious and, very possibly, inten tionally provocative movements, and there was a show of military force by both parties. In violation of international amities, and practically in disobedience of orders, he broke the peace, caused a band of Mexican cavalry mounts to be seized, and prompted some American settlers to occupy Sonoma (June 14, 1846) . This episode is known as the "Bear Flag War," inasmuch as there was short-lived talk of making California an independent State, and a flag with a bear as an emblem flew for a few days at Sonoma. Fortunately for the dignity of history, and for Fremont, it was quickly merged in a larger question, when Commodore John Drake Sloat (178o-1867) on July 7 raised the flag of the United States over Monterey, proclaiming California a part of the United States. The opening hostilities of the Mexican War had occurred on the Rio Grande. The aftermath of Fremont's filibustering acts, followed as they were by wholly needless hostili ties and by some injustice then and later in the attitude of Americans towards the natives, was a growing misunderstanding and estrangement, regrettable in Californian history.

A State of the Union.—By the treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, in 1848, Mexico ceded California to the United States. Gold was discovered, and the new territory took on great national impor tance. The discussion as to what should be done with it began in Congress in 1846, immediately involving the question of slavery. A furious conflict developed, so that nothing was accomplished in two successive sessions; even at the end of a third, in March 1849, the only progress made toward creating a Government for the Territory was that the national revenue laws had been ex tended over it, and San Francisco had been made a port of entry. Meanwhile conditions grew intolerable for the inhabitants. Never was a population more in need of clear laws than the motley Cali fornian people of 1848-49; yet they had none when, with peace, military rule and Mexican law technically ended. Early in 1849 temporary local governments were set up in various towns, and in September a convention framed a free State Constitution and applied for admission to the Union. On Sept. 9, 185o, a bill finally passed Congress admitting California as a free State. This was one of the bargains in the "Compromise Measures of 1850." Meanwhile the gold discoveries culminated and surpassed "three centuries of wild talk about gold in California." Settle ments were completely deserted; homes, farms and stores aban doned. Ships deserted by their sailors crowded the bay at San Francisco—there were 500 of them in July 185o; soldiers deserted wholesale, churches were emptied, town councils ceased to sit, merchants, clerks, lawyers and judges and criminals, everybody in fact, flocked to the foothills. It is estimated that 8o,000 men reached the coast in 1849, about one-half of them coming over land; three-fourths were Americans. Rapid settlement, excessive prices, reckless waste of money, and wild commercial ventures that glutted San Francisco with all objects usable and unusable, made the following years astounding from an economic point of view; but not less bizarre was the social development, nor less extraordinary the problems of State-building in a society "morally and socially tried as no other American community ever has been tried" (Royce). There was, of course, no home life in early California. In 185o women numbered 8% of the population, but only 2% in the mining counties. Mining times in California brought out some of the most ignoble and some of the best traits of American character. Through varied instruments—lynch law, popular courts, vigilance committees—order was, however, enforced as time went on, until there was a stable condition of things.

The slavery question was not settled for California in 1850. Until the Civil War the division between the Whig and Demo, cratic parties, whose organization in California preceded State hood, was essentially based on slavery. The followers of Senator Gwin hoped to divide California into two States and hand the southern over to slavery; on the eve of the Civil War they considered the scheme of a Pacific coast republic. The State was thoroughly loyal when war came. The later '5os are charac terized by H. H. Bancroft as a period of "moral, political and financial night." National politics were put first, to the complete ignoring of excessive taxation, financial extravagance, ignorant legislation, and corruption in California.

Land Grants.

One legacy that must be noted is that of dis puted land grants. Under the Mexican regime such grants were generous and common, and the complicated formalities theoretic ally essential to their validity were very often, if not usually, only in part attended to. Instead of confirming all claims existing when the country passed to the United States, and so ensuring an immediate settlement of the matter, the U.S. Government under took through a land commission and courts to sift the valid from the fraudulent. Claims of enormous aggregate value were thus considered, and a large part of those dating from the last years of Mexican dominion, many probably antedated after the commission was at work, was finally rejected.In State gubernatorial elections after the Civil War the Demo crats won in 1867, 1875, 1882, 1886, 1894; the Republicans were successful in all the other contests. Features of political life and of legislation after 1876 were a strong labour agitation, the struggle for the exclusion of the Chinese, for the control of hydraulic-mining, irrigation, and the advancement by State aid of the fruit interests. Labour conditions were peculiar in the decade following 1870. Mining, war times, and the building of the Central Pacific had up to then inflated prices and prosperity. Then there came a slump; probably the truth was rather that money was becoming less unnaturally abundant than that there was any over supply of labour. The dismissal by the Central Pacific lines (principally in 1869-70) of some 15,000 Chinese, who flocked to San Francisco, augmented the discontent of incompetents, of disappointed late immigrants, and the reaction from flush times. Labour unions became strong and demonstra tive. This is called the "sand-lots agitation" from the favourite meeting-place (in San Francisco) of the agitators. The outcome of these years was the Constitution of 1879, and the exclusion of Chinese by national law. Congress re-enacted exclusion legisla tion in 1902. All authorities agree that the Chinese in early years were often abused in the mining country and their rights most unjustly neglected by the law and its officers. The exclusion had much to do with making the huge single crop ranches unprofitable and in leading to their replacement by small farms and varied crops.

One outcome of early mission history, the "Pious Fund of the Californias," claimed in 1902 the attention of the Hague Tribunal (see ARBITRATION, INTERNATIONAL: The Hague cases). In 1906-07 there was throughout the State a remarkable anti-Japanese agita tion, centring in San Francisco (q.v.) and affecting international relations and national politics.

The Japanese question. was brought to an acute situation in 1913 by the Webb Alien Land Holding Act, which prevented Japanese from holding real es tate. The question was then taken up diplomatically between the United States and Japan, and as a result Japan agreed to the exclusion of further immigration of her citizens to the United States. The period 1910-25 was one of reforms, through the me dium of legislative changes, which were both numerous and far-reaching. In addition to legislative enactments, 78 constitu tional amendments were approved. These changes tending gener ally to increase the cost of government, led to a political reaction which culminated in a further constitutional provision for an executive budget and in the election on an economy platform of Friend W. Richardson as governor in 1922. Four years later the pendulum swung again toward more liberal spending with the election of Clement C. Young. Governor James Rolph followed in 1930 and upon his death, June 2, 1934 was succeeded by Lieut. Gov. Frank F. Merriam.

Reacting with the rest of the country to the economic crisis and to the seeming inability of the Republican national adminis tration to cope with affairs, California, President Hoover's own state, went Democratic in 1932 by a vote of 3 to 2. More phe nomenal still, in the contest of 1935, Upton Sinclair, socialistic novelist, captured the Democratic nomination for governor with his radical EPIC scheme to "end poverty in California." He failed, however, to secure unqualified endorsement from the na tional party and consequently lost to Merriam by 240,000 votes.

In the national election of 1936 California went Democratic, casting no less than 68% of her popular vote in favour of the election of Franklin D. Roosevelt for president, and John N. Garner for vice-president.

BIBLIOGRAPHY.-For lists of works on California, see Robert E. Bibliography.-For lists of works on California, see Robert E. Cowan, A Bibliography of the History of California and the Pacific West, 1510-1906 (I 914) ; Charles E. Chapman, "The Literature of California," in the South-western Historical Quarterly (vol. xxii., 1919) • published in revised form in his A History of California; the Spanish Period.

The best short histories of California are: C. E. Chapman,

A History of California: the Spanish Period (1921) and R. G. Cleland, A History of California: the American Period (1922). See also Henry K. Norton, The Story of California from the Earliest Days to the Present Time (1913) ; Irving B. Richman, California Under Spain and Mexico 5535 1847 (191I) ; C. E. Chapman, The Founding of Spanish California, 1687-1783 (1916) ; Z. S. Eldredge, editor, History of California (5 vol., 1915) ; and S. E. White, The Forty-Niners; A Chronicle of the Cali fornia Trail and El Dorado (1918, Chronicles of America series) . Of general scope and fundamental importance is the work of two men, Hubert H. Bancroft and Theodore H. Hittell. The former has pub lished a History of California, 1542-1890 (7 vol., San Francisco, 1884 90), also California Pastoral, 5769-5848 (1888), California Inter Pocula, 5848-56 (1888) , and Popular Tribunals (2 vol., 1887) . These volumes were largely written under Bancroft's direction and control by an office staff, and are of very unequal value ; they are a vast store house of detailed material which is of great usefulness. As regards events the histories are of substantial accuracy and adequacy. Written by one hand, and- more uniform in treatment, is T. H. Hittell's History of California (4 vol., San Francisco, 1885-97) .The earliest historian of California was Francisco Palau, a Fran ciscan, the friend and biographer of Serra ; his most important work was "Noticias de la Nueva California" (Mexico, 185 7) in the Doc. Hist. Mex., ser. iv., tom. vi.-viii. ; also San Francisco (4 1874) • See in this connection Francisco Palau, Historical Memoirs of New California, edit. H. E. Bolton (4 vol., Berkeley, 1927). Of the contem porary material on the period of Mexican domination the best is afforded by R. H. Dana, Two Years Before the Mast (1840, many later and foreign editions) ; also A. Robinson, Life in California (1846) ; and Alexander Forbes, California: A History of Upper and Lower California from their First Discovery to the Present Time (London, 1839) ; see also F. W. Blackmar, Spanish Institutions of the South-west (Johns Hopkins University Studies, 1891) . A beautiful and vivid pic ture of t se old society is given in Helen Hunt Jackson's novel, Ramona (New York, 1884) . For mission period the standard Franciscan work is Zephyrin Engelhardt, The Missions and Missionaries in California (4 vol., San Francisco, 1908-15) . Francisco Palau, Relation Historica de la Vida ... del Fray Junipero Serra (Mexico, 1787), is an impor tant contemporary source. On the "flush" mining years the best books of the time are J. Q. Thornton, Oregon and California (2 vol., New York, 1849) ; Edward Bryant, What 1 Saw in California (1848) ; W. Shaw, Golden Dreams (1851) ; Bayard Taylor, Eldorado (2 vol., 1850) ; W. Colton, Three Years in California (185o) ; and G. G. Fos ter, Gold Regions of California (1884) . On this same period consult Bancroft, Popular Tribunals; D. Y. Thomas, "A History of Military Government in Newly Acquired Territory of the United States," in vol. xx., No. 2 (19o4) of Columbia University Studies in History, Eco nomics, and Public Law; C. H. Shinn, Mining Camps: A Study in American Frontier Government (1885) ; Mary F. Williams, A History of the San Francisco Committee of Vigilance of 1851 (1921) ; J. Royce, California . . . A Study of American Character, 1846-1856 (Boston, 1886) ; Cardinal L. Goodwin, The Establishment of State Government in California, 5846-50 (1914) ; and, for varied pictures of mining and frontier life, the novels and sketches and poems of Bret Harte.

For government

see David P. Barrows, Government in California (1925), an elementary work; the California Blue Book; and the reports of the various officers, departments, and administrative boards of the State Government. On population, industries, etc., consult the volume of the Fourteenth United States Census; the Agricultural Year Book; the biennial Census of Manufactures; the California Agricultural Experiment. Station, Bu'lle'tintr etc. See also C. F. Saunders, Finding the Worth-while in California 0930).