Calorimetrv

CALORIMETRV, is the scientific term for the measurement of quantities of heat and must be carefully distinguished from thermometry, which signifies the measurement of temperature or degree of hotness. Quantities of heat may be measured in various ways by observing the effects they produce. The most important of these effects for the present purpose are (a) rise of tempera ture, (b) a change of state, (c) transformation of electrical or mechanical energy into heat, or vice versa. The object of the present article is to illustrate the various methods of measure ment by reference to historical experiments, to discuss the assump tions made and the experimental difficulties involved in their application, and to compare the results with special reference to the mechanical equivalent of heat, and to the order of accuracy attainable.

The fundamental assumption made in measuring quantities of heat by any method is that the quantity of heat contained in any body in a given state at a definite temperature and pressure must always be the same under the same conditions at any time, no matter what changes the body may have undergone in the interval, provided that it has been restored to its original state. This was assumed by all observers from the earliest times, but was first put in categorical form by Carnot (see HEAT) as the basis of his argument on the motive power of heat by the method of the cycle. It was also assumed as self-evident that the total heat per unit mass of any substance, such as water, in a homogeneous state, must be the same for different portions of the substance when thoroughly mixed to a uniform temperature and pressure. In other words that the heat-content of any body of uniform composition must be simply proportional to its mass, other things being equal. Since it was manifestly impossible to deprive any body completely of heat, the absolute value of the total heat con tents could not be measured in any case; but it sufficed for prac tical purposes to be able to measure the change of total heat be tween any limits, from which the total heat of any substance per unit mass, reckoned from a convenient zero such as o°C., could be inferred for any temperature. But with the rough apparatus employed by the early experimentalists, it appeared that the in crease of total heat was so nearly proportional to the rise of tem perature within the limits of error of their measurements that it sufficed to tabulate for each substance a single specific constant S, called the "specific heat," representing the rate of increase of the total heat with temperature. Taking water as the standard sub stance of specific heat unity, the unit of heat on this system is the quantity required to raise unit mass of water I° in temper ature. In terms of this unit the specific heat s of any other sub stance may be defined as the quantity required to raise unit mass of the substance I° in temperature. It follows that a body of mass m, composed of a substance of specific heat s, will require per degree rise of temperature a quantity of heat represented by the product ms, which is called the "thermal capacity" of the body considered. These approximate definitions, tacitly assuming the constancy of the specific heat, will suffice for the immediate purpose as a basis of discussion of experimental methods of measurement in illustration of the various points in which further precision of statement or manipulation is required in accurate calorimetry.

Method of Mixtures.

The method originally employed in nearly all cases was the familiar method of mixtures as described in textbooks. The apparatus in its simplest form consists of an open vessel, of known thermal capacity, containing a known mass of water at atmospheric temperature and provided with a thermometer and a stirrer. A known mass in of the substance to be tested is heated to a suitable temperature in a separate heater, and is then quickly immersed in the calorimeter. The water is well stirred, and its final temperature is noted as soon as equilibrium has been reached. The loss of heat of the hot sub stance in cooling from its initial temperature to the final tern perature is represented by the product of its thermal capacity ms by the drop of temperature This is equated to the gain of heat by the calorimeter and the contained water due to the rise of temperature which is represented by the prod uct where M includes, in addition to the actual mass of the water, a small correction, called the "water-equivalent," representing a mass of water equivalent in thermal capacity to the calorimeter, thermometer and stirrer. The value of " s is thus obtained in the form, s = M / m, and represents the mean specific heat of the substance tested over the range to expressed in terms of that of water over the range to If specific heats were all constant, as originally assumed, the mean specific heat over any range would be the same as the actual specific heat at any point. But since we know that the specific heat of any substance may of ten vary considerably with tempera ture, it is usually necessary to specify the range of temperature over which the measurement is made. Further, since the scales of different thermometers differ quite appreciably, it is desirable in accurate work to reduce the results to the absolute scale of temperature for the sake of uniformity. It will easily be seen that, unless the specific heat is nearly constant, the familiar method of expression in terms of specific heat becomes rather complicated and difficult to apply. Thus in dealing with cases in which the specific heat is variable, it is usually preferable to express the observations of mean specific heats over large ranges directly in terms of the total heat h, which greatly simplifies the necessary reduction and tabulation of the results. The total heat per unit mass at any temperature is a definite physical property of the substance, and is that most of ten required in practical calculations. The quantity actually measured in an experiment like the above is the drop of total heat, which is equal to where s is the mean specific heat over the same range of temperature. Further examples of this method of expression are given in the later sections of this article.

One of the chief sources of uncertainty in all calorimetric experi ments is that heat cannot be perfectly insulated or prevented from escaping. Thus in the simple experiment above described, some heat is lost while the heated body is being transferred to the calorimeter, some heat is lost from the calorimeter as soon as its temperature is raised above that of its surroundings, and some is usually lost by evaporation from the exposed surface of the water. The degree of accuracy attainable in the measure ments depends to a great extent on the possibility of preventing all such losses as are avoidable, and of estimating those which can not be eliminated. Various methods of effecting this desirable result are described and compared with special reference to the problem of determining the variation of the specific heat of water, which is one of the most fundamental questions in calorim etry, and affords many good illustrations of the difficulties to be encountered in accurate work.

Variation of the Specific Heat of Water.

It would appear at first sight to be a simple matter to test the constancy of the specific heat of water by mixing equal weights of water at differ ent temperatures and observing whether the final temperature of the mixture was the mean of the two initial temperatures. In reality the result of any such experiment would depend quite as much on the scale of the thermometers employed, and on uncer tainties of heat-loss, as on the actual variation of the specific heat. M. V. Regnault, who made so many advances in calorimetry and thermometry, appears to have come to the conclusion by making some tests of this nature that the variation of the specific heat, at temperatures such as are used in calorimetry, was too small to be detected with certainty. He also made some very elaborate measurements on a large scale with water from a boiler under steam-pressure, over the range from I 10° to I 90°C., which showed that the total heat h of water increased somewhat more rapidly at higher temperatures and pressures in a manner which could be represented within the limits of error of his experiments by the simple formula, h (I) The corresponding value of the specific heat s at any tempera ture t was deduced by differentiation, thus, s=dh/dt=I-+ (2) These formulae were accepted for more than 5o years as the basis of calculation in steam-engine practice, for which they afforded ample accuracy. They implied a gradual increase of spe cific heat, starting from the value I at o ° C. and reaching I.00116 at 20°, 1.00425 at 50°C., and 1.0130 at Ioo°C., thus confirming the conclusion that the variation of the specific heat at ordinary atmospheric temperatures was too small to be worth taking into account in calorimetric experiments, the accuracy of which under the best conditions rarely exceeded 2 or 3 parts in i,000.Many able experimentalists who succeeded Regnault found much larger rates of increase of the specific heat at ordinary tem peratures. Many of their methods were highly ingenious, but their results were so discordant as to leave little doubt that the remarkable discrepancies between different observers were due mainly to lack of appreciation of the difficulty of the problem. The first reliable indication of the true mode of variation between o° and 40°C. was that obtained by H. A. Rowland (see below) in his experiments on the mechanical equivalent of heat. His obser vations led to the totally unexpected result that the specific heat of water, instead of increasing steadily with rise of temperature from the freezing point, showed at first a fall of more than 1%, reaching a minimum at 30°, after which a slight increase was indicated. But owing to the rapid increase of the heat-loss at higher temperatures the observations were not continued beyond 35°C. Rowland himself was doubtful on this account about the exact position of the minimum, and considered that the specific heat might go on decreasing as far as 40°. The fact of the diminution of the specific heat in this region was soon verified by many independent observers, though they differed somewhat in the rate of diminution and in the position of the minimum. But they differed so widely at higher temperatures that they did not throw any light on the relation between the thermal unit at 20°C., as employed in the method of mixtures, and the mean thermal unit from o° to roo°C., as commonly adopted by engi neers and used in ice-calorimetry.

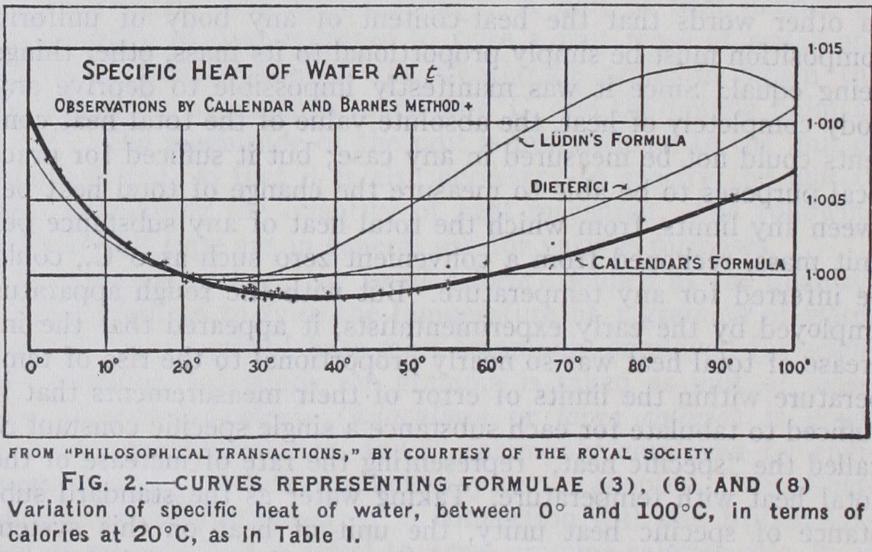

The first investigation covering the whole range o° to oo°, in which due attention was paid to the thermometric difficulties, was that made by Ludin (Zurich, 1895) under the direction of Prof. Pernet, employing the method of mixtures with mercury thermometers of the Paris type. The results were probably as good as could be obtained by the method employed, which is not very suitable for the purpose, since the highest observation with the hot water at 97° does not give the actual specific heat at 97°, but only the mean specific heat from 97° to 18°, the final tem perature of the calorimeter. The quantities of hot water added were adjusted to give nearly the same rise of temperature, I I° to 18°, in the calorimeter in each case, so that the mean specific heat of the hot water over each range could be compared with the same standard. The observations of the mean specific heat, six of which were taken for each of ten ranges, seldom differed by more than 2 or 3 parts in i,000 from the mean at each point, but may have been liable to systematic errors due to evaporation or similar causes. The deduction of the formula for the actual specific heat from the observed values of the mean specific heat over different ranges is a somewhat indirect process which greatly increases the uncertainty of the values of the actual specific heat in the region near i 00°C. LUdin's formula for the actual specific heat s at any temperature t between o° and i oo° C. is often quoted, and is as I —O.07668 (t/ioo)+0.196 I16 (3) *0.00025 *0•040 *0.030 The probable errors of the coefficients, as calculated by LUdin, are given in the line below the formula itself. The curve repre sented by this formula is shown by the line marked "LUdin's formula" in fig. 2. It shows a minimum at 25°C. followed by a rapid rise to a maximum at 87°, and falls rapidly beyond Ioo° instead of rising continuously like Regnault's curve given by formula (2) . But a formula of this type, in which the coefficients are large and of opposite signs, cannot be trusted for extrapolation.

Method of Electric -Heating.

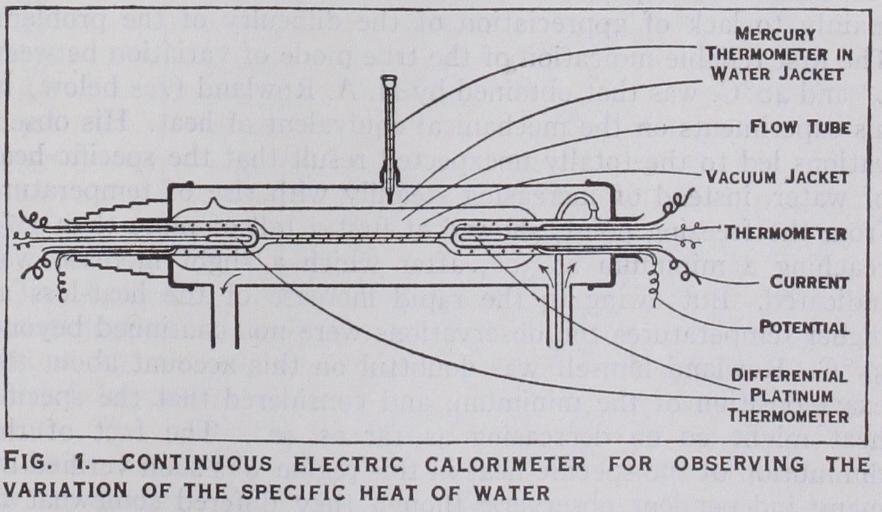

The method of electric heat ing, which is now commonly applied for measuring specific heats at high or low temperatures, offers special advantages for the variation of the specific heat. After the substance to be tested has been heated or cooled to any desired temperature in a suitable thermostat, a measured quantity of heat is imparted to it by an electric heating coil, sufficient to produce a small rise of tem perature, which is carefully measured. The actual specific heat is thus obtained over a small range at the desired point, in place of the mean specific heat over a large range of temperature. The method has the additional advantage that the heat-loss in trans ference, which is such an uncertain element in the method of mixtures, may be entirely avoided, since the substance is heated after being placed in position in the calorimeter.The arrangement shown in fig. I was employed by H. L. Callen dar and H. T. Barnes (Phil. Trans. 1902) in applying the electric method to the variation of the specific heat of water. A steady current of water flowing through a fine tube from B to A is heated during its passage by a steady electric current through a central conductor of suitable resistance. The current produces a steady difference of temperature between A and B, which is meas ured by a single reading with a differential pair of platinum thermometers (see THERMOMETRY). The flow-tube and the ther mometer pockets at either end are protected from heat-loss by enclosure in a silvered vacuum jacket, which is surrounded by an external water jacket maintained at the desired temperature by a vigorous circulation of water from a delicate thermostat. The adoption of a steady-flow method eliminates all the discon tinuities of operation which are so troublesome in the method of mixtures. After turning on the electric current and allowing suffi cient time for the temperature to become perfectly constant in the outflow pocket A, the water current through AB is switched over into a weighing flask (not shown in the figure) without alter ing any of the conditions, and is collected for a suitable interval of time, recorded on an electric chronograph, in order to deduce the flow m in gm. per second. Meanwhile one observer records the difference of temperature dt between A and B, which remains practically constant, while another records the difference of poten tial E between the ends of the central heater and the current C passing through it by means of a potentiometer. The water equivalent of the calorimeter, consisting mainly of the outflow pocket A, is very small, and is not required at all in the calcula tion if the temperature is constant. Sufficient stirring is effected by causing the water to circulate spirally round the bulbs of the thermometers and round the central heater in the flow tube AB. The heat generated by the stirring can be measured by observing the difference of pressure between A and B, but never exceeds i in io,000 of the heat supplied electrically. The temperature of the external water jacket, which is always nearly the same as that of the inflow pocket B and of the thermostat, is not required with great accuracy, and is read by the mercury thermometer shown in the figure. The use of a differential pair of platinum thermometers for measuring the rise of temperature dt of the water in passing through the fine flow tube (which is required with the greatest accuracy) ensures that the observation shall be simultaneous for both thermometers, and avoids the uncertain corrections for change of zero and for stem-exposure to which even the best mercury thermometers are liable.

The steady-flow method possesses the advantage that the exter nal loss of heat is greatly reduced and is rendered more regular, so that it becomes easier to measure with certainty. There is no free surface of water to permit loss by evaporation as in an open calorimeter. The vacuum jacket eliminates the possibility of loss by convection or by deposition and evaporation of dew, which are common sources of trouble in calorimetric experiments by other methods, but it cannot entirely eliminate losses by conduction or radiation. The direct determination of these residual losses, by experiment at each observation, is readily effected by the follow ing method.

The rate of heat supply by the electric current in watts is given by the product EC, and is equal to the rate at which heat is being carried off by the water together with the rate of heat loss by conduction and radiation; these may be expressed in watts and represented by the products Jsmdt and li dt, respectively, since both are proportional to the rise of temperature dt. We thus obtain the general equation of the method, in which Js is the variable specific heat to be determined in joules or watt-seconds per gram per degree rise of temperature, m is the flow of water in grams per second, and It is the rate of heat loss in watts per degree rise. A second observation is then taken at the same temperature with a different value of the water flow m, and the current C is adjusted to give the same rise of temperature. We thus obtain a second equation in which the term h dt is the same as in (4) and can be eliminated by sub traction. The required value of Js is thus obtained in the form, where the quantities observed in the two separate flows are dis tinguished by dashes. In practice it is seldom possible to get the rise of temperature precisely the same in both observations, and the other theoretical conditions cannot be satisfied exactly, but it is easy to allow for any small deviations of this kind by making slight modifications in the calculation.

The results obtained by this method over the whole range o° to i oo° C. can be represented satisfactorily by the following formula :— in which the value of the constant 0•98536 is adjusted to make s = r when t = zo°, or the specific heat is expressed in terms of a unit at 2o° C. The other terms are small and positive, and can be calculated with ample accuracy for all possible purposes by means of a loin. slide rule. The corresponding curve is shown by the line marked "Callendar's formula" in fig. 2. Some of the separate observations, taken with six different calorimeters, are plotted in the figure in order to indicate the order of agreement obtained. Liidin's observations could not be plotted in the same way, since they did not represent the actual specific heat at any point but only the mean specific heat over considerable ranges. Formula (6) shows a minimum at 37.5°C., and differs from Liidin's by about 1% between 7o° and go°C., but shows no sign of a maximum, and con tinues to rise at a rate very sim ilar to Regnault's formula (2), with which it agrees closely at zoo° C. It is not intended for extrapolation above ioo°C. as it represents the specific heat at a constant pressure of i atmosphere, which cannot be directly measured at temperatures above the boiling-point.

The figures in the column headed "Specific Heat" show the variation given by formula (6). It will be seen that the specific heat at i5° exceeds that at zo° by little more than i in i,000, which is beyond the limits of error of ordinary calorimetric experi ments. The figures in the next column give the corresponding values of the total heat h obtained by integrating the same formula for the specific heat. The mean thermal unit over the range o° to i oo ° is obtained by dividing the value of li at r oo ° by i oo, and is seen to be i•ooi6 times the specific heat at zo°. The mean specific heat over any range is most easily obtained from this column by dividing the drop of total heat by the corresponding drop of temperature. But for most experiments in which large ranges of temperature are used in the calorimeter the converse process is required, namely, to deduce the drop of total heat h'–h" from the observed drop of temperature t'–t". This is most easily done by adding the small difference h'–t', and subtracting h"–t", which may be obtained from the table by inspection.

In comparing results obtained by different methods it is always desirable to go back to the quantities actually measured, whenever possible. Rowland in his experiments observed the increase of total heat from 5° to 35° in mechanical units, which are reduced to thermal units in the column headed "Rowland" by dividing by his value of the mechanical equivalent at 20°. His results thus reduced are seen to agree very closely with those found by the electric method over the same range, although the values of the specific heat for successive intervals of 5° (which are generally taken as the basis of comparison) are somewhat irregular owing to the increasing uncertainty of the heat-loss towards the latter part of the range. Similarly in Liidin's experiments, the quantity measured was not the specific heat at t, but the drop of total heat of the hot water (or the gain of total heat of the cold water) introduced into the calorimeter. His values of the total heat agree as closely as could be expected with the continuous electric method from 0° to 40°. Beyond 40° they show an increasing divergence, which amounts, however, to only 0.2% at 70°, where his curve of specific heat shows a discrepancy of nearly i%.

Ludin's curve of specific heat was reproduced with remarkable fidelity by W. R. and W. E. Bousfield (Phil. Trans. 1911), who employed a most ingenious method of electric heating in a Dewar flask calorimeter. They measured the rise of temperature with mercury thermometers, and were unable to extend the observa tions beyond 80° on account of evaporation from the surface of the water. When expressed in terms of total heat, the dis crepancies of their results from formula (6) are somewhat smaller than those of Liidin's formula, and may probably be attributed to uncertainties of heat-loss by evaporation, etc., at the upper limit of their range, or to errors due to stem-exposure and vari ations of zero such as are inevitable with mercury thermometers, or possibly to the difficulty of determining the water-equivalent of the calorimeter and heater satisfactorily. In any case the type of variation shown by Liidin's curve for the specific heat, with a maximum below I oo° followed by a rapid fall at higher tempera tures, is quite inadmissible on theoretical grounds, besides being in contradiction with the results of experiments at higher tempera tures, all of which appear to require a cont inuous increase of the specific heat with rise of temperature.

Theoretical Explanation of the Variation.

Rowland sug gested that the increase of the specific heat of water on approach ing the freezing-point should be due to an increasing proportion of molecules of ice in the liquid. Assuming that each ice molecule in melting absorbs a quantity of heat equivalent to its latent heat of fusion, the proportion of ice molecules in water at the freezing point would be something in the order of 1% of the mass. Nearly all of these would be melted by the time the water reached a temperature of 40°, where the specific heat has already begun to increase again. H. T. Barnes has succeeded in measuring- the specific heat of supercooled water below the freezing point, and finds that it continues to increase as the temperature falls, follow ing a prolongation of the same curve as that found above the freezing point. The high specific heat of water has often been attributed to the complexity of the water molecule, which has been the subject of much speculation; but it is futile to specu late until something definite is known of the nature of the poly mers present and the laws of equilibrium between them. There is no doubt that the formation and dissociation of complex molecules must profoundly affect the specific heat.In the case of the vapour, on the other hand, there is little doubt that the great majority of the molecules of steam are single molecules of the type (See VAPORIZATION.) It appears highly probable that a certain proportion of steam mole cules must also exist in solution in the liquid when in equilibrium with the vapour in the state of saturation, and that these mole cules are chiefly responsible for the increase of specific heat of the liquid. According to the vapour-pressure theory of osmotic pres sure (see THERMODYNAMICS) the surface of any liquid acts as a semi-permeable membrane, which allows free passage to the vapour-molecules. This implies that the density of the vapour molecules in the liquid should be the same as that of the vapour with which it is in equilibrium, or that water at any temperature should contain its own volume v per unit mass of saturated steam at the same temperature. Since a volume v of steam already exists in the water in the state of vapour, the vaporization of unit mass of water with increase of volume from v to V (the corre sponding volume of steam) involves the vaporization of a volume V-v of steam. Thus the whole latent heat L of vaporization per unit mass corresponds with the generation of a volume V-v of steam, and the latent heat of the volume v already contained in the water should add the fraction v/(V-v) of L to the total heat h of the water. According to this view, the effect of the steam molecules on the variation of the total heat h of the liquid, reck oned from 0°C., may be represented by the simple formula: vLI(V (7) A formula of this type, though without any theoretical interpreta tion, was first proposed by Paul de St. Robert (Turin, 1857), as representing Regnault's results between Ioo° and 200°C. just as well as formula (I) . It was also pointed out by J. MacFarlane Gray (Proc. Inst. C.E. 1902) that, by superposing on formula (7) the effect of the ice molecules near the freezing point, a curve very similar to that found by the continuous electric method for the variation of the specific heat between o° and 100°C. would be obtained. Since the effect of the ice molecules becomes evanes cent above 40°C., the simple formula (7) was adopted as the basis of Callender's steam tables (Ency. Brit. 1902), though for mula (6), including the effect of the ice molecules, is still required for calorimetric experiments between o° and 40°.

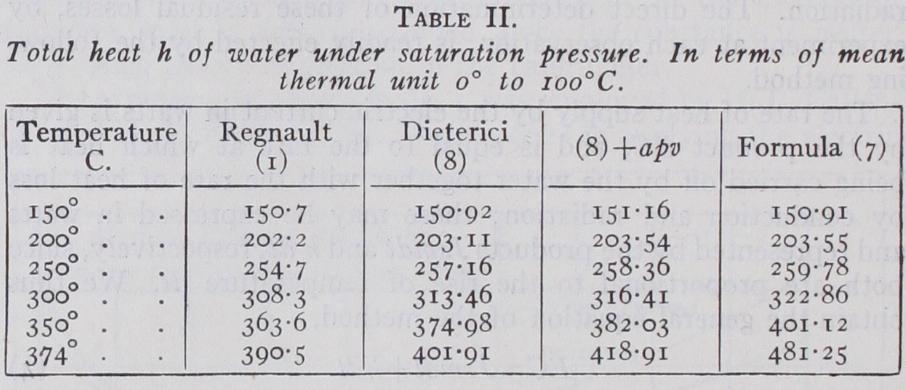

The first column gives the temperature. The column headed Regnault (I) gives values of h by formula (I) reduced in the proportion 100/100.5, since the value of h at ioo°C. is 100 in terms of the mean thermal unit, whereas Regnault's formula (I) gives at Ioo°C. in terms of a unit at o°C. In the case of Dieterici's formula (8) (see below) the values are already expressed in terms of the mean thermal unit. His formula for h is very similar to Regnault's but with different coefficients. Both are liable to the objection that they do not make the total heat increase sufficiently fast to satisfy the theoretical conditions at the critical point, 374°C. The values of the thermodynamic formula (7) are expressed in terms of the mean thermal unit by choosing the value of the constant to be 0.99666, which is very nearly the same as the minimum value of the specific heat 0.99697 given by formula (6) in terms of the mean thermal unit.

Method of Fusion.—The measurement of quantities of heat in terms of change of state, e.g., fusion of ice or condensation of steam at constant temperature, is theoretically the most perfect in that no question of the thermometric scale is directly involved. The practical difficulties encountered by Black and other observers (see HEAT) in applying the method of fusion lay in the measure ment of the quantity of ice melted. These troubles were first successfully overcome by R. Bunsen (Phil. Mag. 1871), who con structed an apparatus in which the diminution of volume due to the melting of the ice could be observed. The construction of a modern calorimeter of this type is illustrated in fig. 3. The cen tral tube A serving for the reception of the heated body is sur rounded by a bulb B filled with air-free water, which communi cates at its lower end with a tube C of small bore containing mercury, by which any changes of volume of the water in freez ing or melting can be observed with considerable accuracy. The vacuum jacket J surrounding the bulb B was not included in Bunsen's original design but is a later addition intended to elimi nate creep of zero, as explained below. In using the instrument, the first operation is to freeze some of the water in B by circu lating a freezing liquid, such as alcohol or ether at a low tem perature, through the inner tube A, which thus becomes coated with a sheath of ice. The whole apparatus is then immersed in a bath of melting ice, leaving only the upper end of A and the tube C exposed. If a hot body is now dropped into the tube A, the quantity of heat which it gives up in cooling to o°C. will melt a corresponding amount of the ice sheath. The quantity of ice melted is shown by the retreat of the mercury along the tube C, or preferably by observing the weight of mercury sucked into the tube as in using a weight thermometer. Since the weight thus observed is directly proportional to the quantity of heat added, and is independent of the dimensions of the calorimeter, the con stant factor for reducing weight of mercury drawn in to gram calories of heat added is the same for all ice-calorimeters of this type. The constant is usually determined by adding known quanti ties of heat in the form of water at its boiling-point. Dieterici (Ann. Phys. 1905) used the method for observing the variation of the mean specific heat of water at temperatures up to 300°C., by sealing known weights of water in quartz-glass bulbs which were heated to various temperatures and dropped into an ice calorimeter. By using thin bulbs heated to Ioo°C. he was thus able to determine the constant of the ice-calorimeter in terms of the mean thermal unit with an accuracy not previously achieved. The value found was 15.492 mg. of mercury per mean gram calorie centigrade, in place of the value 15.44 previously employed as the mean of the results of other workers. Dieterici's value of this important constant has since been confirmed by E. Griffiths (Proc. Phys. Soc. 1913), who found 15.491 mg. of mercury as the equivalent of the mean gm. calorie of 4.185 joules, as given by the electric method shown in fig. 1.

The chief advantage of the ice calorimeter is that it is very perfectly protected against external loss of heat provided that the internal ice sheath is sufficiently continuous to prevent any heat escaping directly from the heated body to the external ice bath, and that the temperature of the ice bath is precisely the same as that of the ice sheath inside the calorimeter. Sometimes there may be a slight difference in quality of the ice, causing a gradual creep of zero when the calorimeter is directly immersed in the ice bath. This creep of zero, which is often troublesome in delicate experiments, may be completely eliminated, as has been explained by H. L. Callendar (Ency. Brit. 1902), by enclosing the bulb of the calorimeter in a vacuum jacket, as indicated in fig. 3, which reduces any possible interchange of heat about I,000 times as compared with direct immersion of the calorimeter in the ice bath. The method is then very convenient for measuring small quantities of heat, such as those due to the Peltier effect (see also ELECTRICITY), especially when the heat is generated inside the calorimeter. The risk of heat-loss in transference can not be avoided, any more than in the method of mixtures, if the heated body has to be dropped into the calorimeter, though the uncertainty may be reduced by skilful manipulation.

The most important correction in Dieterici's experiments on water was that for the thermal capacity of the quartz bulbs, which amounted to about a quarter of that of the contained water in the experiments at Ioo° to 130°C., and was calculated from a for mula for the specific heat of quartz-glass. He estimated the order of accuracy of the experiments at Ioo°C. as I in i,000 on the mean specific heat, but stated that the precision attainable dimin ished at lower temperatures as the quantity of heat to be measured was reduced. For this reason the method was not suited for giving accurate results for the variation of the specific heat near the freezing point. The correction for the water equivalent of the quartz bulbs became more important at higher temperatures, where it was necessary to use much thicker bulbs in order to with stand the steam pressure. From 15o° to bulbs having a ther mal capacity about equal to the contained water were employed. Above this point up to 300°, the limit of the experiments, the bulbs had a capacity nearly 4 times that of the water, which would greatly increase the uncertainty of the results. Another small correction was applied for the internal latent heat of the steam generated in the space left vacant above the water level, since the bulbs could not be completely filled without risk of bursting under the enormous pressures which might be generated by the expansion of the water. When these corrections are applied the quantity measured, as Dieterici points out, is the drop of internal energy of the water in cooling to o°C. from its initial temperature, since the water is enclosed in a practically non expansive envelope, and no external work is done either in heat ing or cooling. Thus the formula given by Dieterici for the mean specific heat t from o° to t, namely (8) when multiplied by t, represents the internal energy of water at t under saturation pressure, reckoned from o°C. and expressed in terms of the mean thermal unit, giving t= I when t= I oo. This formula gives slightly higher values for the internal energy than Regnault's formula (I) for h, as shown in Table II., and has commonly been adopted for the total heat of water by Conti nental and American writers on the subject. But in order to deduce the total heat h from the internal energy, the quantity apv should be added, representing the thermal equivalent of the work required to pump a volume v into a boiler against the steam pressure p. This correction is indicated in the next column of Table II. and gives higher values than (8), agreeing very well with the thermodynamic formula (7) up to 200°C., but still fall ing short of the rapid increase shown by (7) near the critical point. The corresponding formula for the specific heat s at t, as obtained from (8) by differentiation, and expressed in terms of a unit at 20°C., is represented by the curve marked "Dieterici" in fig. 2. As Dieterici remarks, the formula for s has an inferior degree of accuracy to that representing the mean specific heat, so, t since it does not so directly represent the results of observa tion. Some additional uncertainty in the reduction arises from the value of the unit at 20°, which Dieterici gives as 0•9974 in terms of the mean unit, in place of the value 0.9984 given by the continuous electric method. The agreement of these two values to 1 in I,000 coincides with Dieterici's estimate of the limit of accuracy of the ice calorimeter.

Method of Condensation.

The Steam Calorimeter, in which quantities of heat are measured in terms of the latent heat of condensation of steam, has been applied with success by J. Joly (Proc. R.S. 1889) to the difficult problem of measuring the spe cific heats of gases at constant volume, and is undoubtedly capable of giving very accurate results under suitable conditions. But its use for accurate work is practically restricted to the range from atmospheric temperature to zoo°C., and it is of less general applicability than the ice calorimeter. The method also requires very delicate weighing of the quantity of steam condensed, as rgm. calorie corresponds to the condensation of less than 2mg. of steam. Assuming Regnault's value 536.68 for the latent heat of steam at 200° C., Joly found, by weighing the steam condensed in heating a known mass of water from 12° to 200°C., that the mean specific heat of water between these limits was only 0.995 2, whereas the value given by Regnault's formula was 2.0053, and that given by Lfldin's formula i .0086, exceeding the value found by Joly by more than 2%. Joly's observation was of special inter est at the time (I 895) as the first suggestion that the accepted values of the total heat of water at ioo° and the latent heat of steam were discordant by an amount which could hardly be neglected in the case of such important constants. Joly's obser vation was probably very accurate but gave only the ratio of the two, and not the actual value of either. The truth probably lay between the two extremes, as was subsequently found to be the case. Thus if we take the values of the total heat of water at 12° and zoo°, as deduced from formula (6) and given in Table I., we find the mean specific heat 1.00104 in terms of a unit at 20°C. and deduce for the latent heat from Joly's observation the value 54o.° in place of Regnault's 536.7. The higher value, 540 in terms of a unit at 20°C., has since been confirmed by other observers, though it may still be a little too low on account of the difficulty of eliminating the last traces of moisture in saturated steam or any other vapour. For this reason it is usually preferable, in find ing the total heat, or the latent heat, of a saturated vapour, to observe the total heat at the required temperature t, but at pres sures slightly below that of saturation to make sure that the vapour is dry. Values for the dry saturated vapour may then be deduced by extrapolating the isothermal curves thus obtained on the PT diagram to the saturation pressure.Steady Flow Methods.—In place of measuring the rise of temperature in a fixed mass of water, as in the method of mix tures, it is often preferable, in cases where the heat to be measured can be supplied at a steady rate, to keep the temperature in every part of the apparatus constant by removing the heat as fast as it is generated by means of a steady flow of cooling water. When the conditions have become stationary the rate of heat supply can be measured by observing the rate of flow and the rise of temperature of the cooling water. The method is especially suitable for measurements of the total heat of liquids or vapours, and of the calorific values of gaseous and liquid fuels, which in clude many of the most important cases in practice. It has the advantage that the water equivalent of the apparatus is not required, which greatly facilitates work at higher temperatures and pressures, where the thermal capacity of the apparatus is often large and its accurate determination would be a matter of con siderable difficulty. A steady flow method combined with electric heating has already been illustrated in fig. i. The object in that case was to determine the variation of the specific heat of the steady current of water. The total heat of other fluids in steady flow may then be measured by using a steady flow of water to carry off the heat. In this case there are two flows to be meas ured, but the complication of electric heating is no longer re quired. As a good illustration of the way in which difficulties of measurement may be circumvented by the employment of a steady flow method, we may take the measurement of the total heat of steam at high temperatures and pressures, which is a problem of some practical interest and importance, but has hitherto resisted solution by any of the older methods.

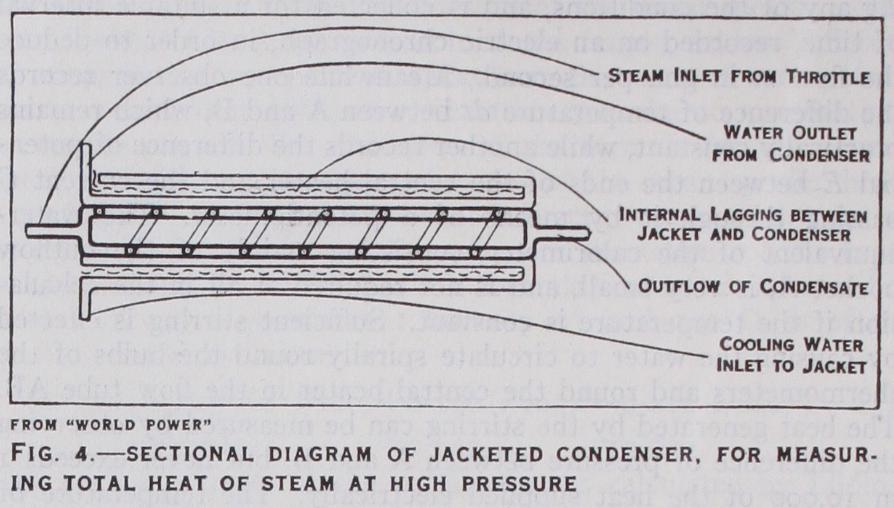

The heart of the apparatus, in which the steam is condensed and its drop of total heat measured, is called a jacketed condenser and is shown in section in the annexed fig. 4, omitting such details of construction as are not essential to the principle of the method. The auxiliary apparatus required for generating a steady flow of steam consists of a feed-pump, designed to work up to a pressure of 4,000 lb. per sq. in., delivering water at the desired pressure to an electric boiler and superheater capable of generating steam and heating it up to the desired temperature. The steam then passes through a thermometer pocket in which its initial tempera ture and pressure are accurately observed, defining the state in which its total heat H1 is to be measured. Immediately on leaving this high-pressure pocket, the steam is passed through a throttle tube (which reduces the pressure to atmospheric without altering its total heat) before entering the condenser through the inlet marked A on the left of the figure. The condenser proper con sists of the annular space between the two inner tubes, in which the steam is caused to circulate spirally, as indicated in the figure, in order to increase the efficiency of condensation. After being condensed to water at atmospheric pressure the steam leaves the condenser at B and passes through a thermometer pocket, not shown in the figure, in which its final temperature as condensate is observed. Its total heat in this state is known from the table already given. Finally the condensate is cooled to atmospheric temperature before being collected in the tanks, which are weighed at suitable intervals in order to determine the flow of steam M in lb./min or gm./sec. or other convenient units.

The steady flow of cooling water by which the steam is con densed is supplied from a large tank in which the level is main tained constant. After passing through a thermometer pocket at C, where its temperature is observed, the cooling water circulates round the jacket shown in the figure, which is separated from the condenser proper by the layer of lagging. It then circulates round the condenser tube, abstracting heat from the steam and rising in temperature, and leaves the apparatus through a thermometer pocket attached to the outlet at D. It is cooled again to atmos pheric temperature on its way to the weighing tank, in which the flow in of cooling water is measured for the same intervals as that of the condensate M by switching over the flows simultane ously into their respective tanks. The function of the jacket, through which the cooling water enters the apparatus, is to catch any heat which might otherwise escape from the hot water sur rounding the condenser. In addition to this, the whole apparatus is enclosed in an external jacket, not shown in the figure, supplied with circulating water from the same tank as the cooling water. This external jacket is protected by lagging and, being always at the same temperature as the internal jacket surrounding the con denser, serves to prevent any heat reaching the cooling water from outside, after its inflow temperature has been measured at C. With these precautions, the external loss of heat from the con denser is almost incredibly small, rarely exceeding a fifth of i %, even with a rise of temperature of 80°C. in the cooling water.

The theory of the method is extremely simple and has the advantage of giving the result directly in terms of total heat, without any ambiguity with regard to the quantity measured. The kinetic energy of flow through the pockets being negligible, when everything is steady, the rate at which heat is being carried in by the steam, namely must be equal to the rate at which heat is being carried off by the condensate and the cooling water, namely together with the rate of heat-loss X from the high-pressure pocket, and x from the condenser. Divid ing each of these quantities by M, so as to obtain the total heat of the high-pressure steam per unit mass, we find the equation, It should be observed that H2 and X + x are small compared with HI, and that the term requiring the greatest accuracy of measurement is the gain of total heat of the cooling water. This is always very nearly equal to the corresponding rise of temperature, as directly measured with a differential pair of plati num thermometers, from which the gain of total heat is easily de duced by adding and subtracting the small differences shown in Table I. between h and t, as previously explained. The rates of heat-loss, X and x, can be found, as in the continuous electric method, by varying the flows M and m independently in suitable ratios. This is more troublesome than in the electric method, but need not be repeated at every observation if the same apparatus is employed for a considerable period.

It might be thought that it would be necessary to condense the steam under its original pressure in order to measure the total heat. This was the case according to the old definition of the total heat by Regnault, who actually measured the total heat of steam in this way up to i2 atmospheres. Owing to the high pressure, he met with many difficulties from leakage and measured the total heat of water in a different way, which led to awkward discrep ancies in the theory. With the new definition of total heat, first proposed by Callendar in a previous edition (Ency. Brit. 1902), and now generally accepted, all these difficulties and discrepancies disappear, and the steam may be condensed at any convenient pressure without affecting the results for the total heat. The ad vantage of condensing always at atmospheric pressure is that only one design of condenser is required. Moreover the best security against any possibility of leakage between the steam and the cool ing water is obtained, since the perfect absence of leakage may be tested at any time by employing much higher pressures. Never theless it is essential, in order to secure permanent immunity from leakage, to design the condenser in such a way that every tube is perfectly free to expand. Otherwise it would rack itself to pieces in time by differences of expansion between the hot and cold tubes. In practice both the inside and the outside of the annular space are utilized for condensing the steam, by making the cooling water circulate through the whole length of both. But these de tails of construction could not be shown in the diagram without obscuring the main principle.

It is a great advantage of the method that the same apparatus, without any modification, can be applied for measuring the total heat of water by simply pumping hot water through it. In point of fact it was first designed with the object of verifying the ther modynamic formula (7) for the variation of the total heat of water at high pressures near saturation; but owing to the difficulty of procuring the expensive apparatus required for high pressures it was first applied (Phil. Trans. 1912) to the verification of Table I. for the total heat between o° and too°C. as deduced from the observation of the specific heat by the continuous electric method. Since the World War, with the assistance of the British Electrical Research Association, who provided the necessary funds, it has been possible to extend the measurements for both steam and water to pressures in some cases exceeding 3,50o lb. There was no difficulty in measuring the total heat h of water at high pressure provided that the temperature was 2° or 3° below that of satura tion; but, at or near the saturation point, any trace of air in the water caused profuse generation of steam in the air bubbles and tended to give results appreciably higher than equation (7) . This difficulty was surmounted by supplying the pump with distilled water from a special apparatus, by which it was freed from air immediately before passing into the pump. This led to so great an improvement that there seems to be little doubt that equation (7) holds up to the critical temperature where the volume of water becomes indeterminate. The actual value of h at the critical point, as given in Table II., remained uncertain, so long as the corresponding value of the volume v rested on theoretical as sumptions, such as those of van der Waals, which were very doubtful, if not entirely erroneous. But both h and v have now been determined by direct experiment at this point, and are found to satisfy formula (7).

Mechanical Equivalent of Heat.—The history of the estab lishment of the mechanical theory of heat is reviewed in the article HEAT, in which a general account is given of the early ex periments by Joule and others demonstrating the transformation of other kinds of energy into heat. The phrase "mechanical equiv alent" was originally employed to denote the number of gravita tional units of mechanical work, such as foot-pounds or kilogram metres, required to produce one unit of heat when completely converted into heat by friction or otherwise. By a natural process of transition the same phrase is now commonly used for the nu merical ratio of equivalence between units of energy in any form and the various units of heat. Since most forms of energy are measured directly or indirectly in terms of mechanical work done against gravity, it is merely a question of conversion of units, when one value of the mechanical equivalent of a particular ther mal unit has been found by experiment, to deduce the correspond ing result for any other thermal unit in terms of any other unit of energy. Owing to the multiplicity of units both of energy and heat, there are many different values for the mechanical equivalent on this basis; but for scientific purposes it is usual to reduce ex perimental results to absolute units on the C.G.S. system, taking the joule or watt-second as the absolute unit of energy and the gram-calorie centigrade at 20°C. on the scale of the hydrogen thermometer as the unit of heat. This has the advantage of ex cluding the effect of local variations of gravity and fits con veniently with the electrical system of units. Engineers, on the other hand, still prefer the gravitational system as fitting better with the practical measurement of pressure in terms of weight per unit area, since the variations of gravity are relatively small and can be taken into account if necessary in special cases.

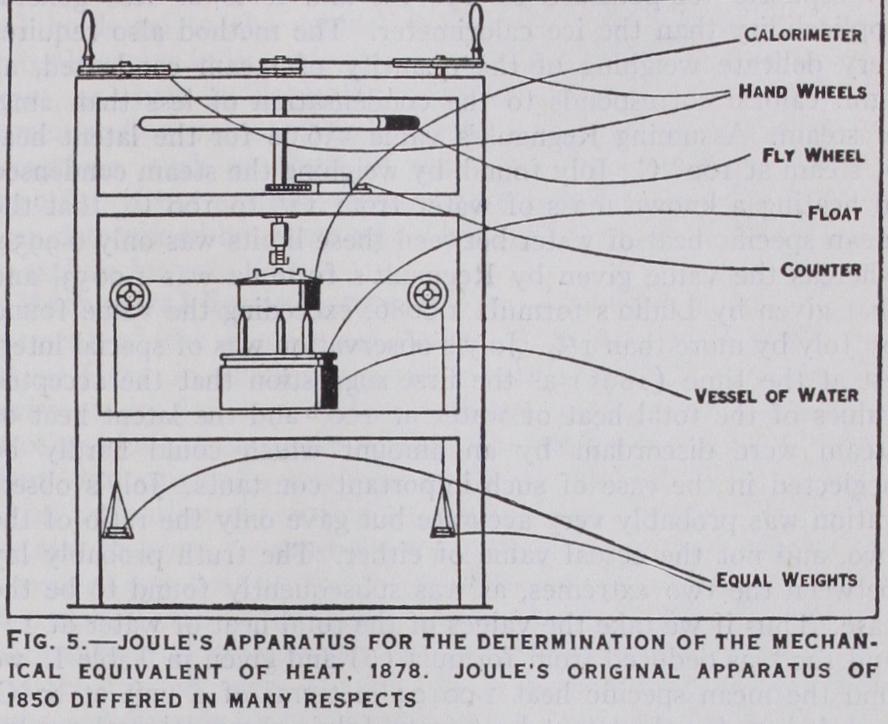

The experimental measurement of the mechanical equivalent of heat requires the accurate determination of the quantity of heat generated by the expenditure of a known amount of mechanical work, and is mainly a question of calorimetry. The simplest method to use in the laboratory is the electric method, since the measurement of electric energy requires no moving parts in the apparatus, and is very accurate if the absolute values of the electric standards employed are known. Accordingly as soon as the absolute value of the ohm had been determined by the committee of the British Association, the electric method of calorimetry was applied to the verification of Joule's determination of the mechan ical equivalent of heat. The result gave a value more than 1% lower than the mechanical method employed by Joule in 185o. As these early experiments had been carried out on a small scale with a very laborious method of measuring the work and applying corrections for heat-loss, Joule consented to repeat them on a much larger scale with a greatly improved method, as shown in fig. 5. The calorimeter h containing about 12 lb. of water, was supported on a float w in a vessel of water v, so as to be in neutral equilibrium, but was kept at rest by a pair of fine strings passing round a horizontal wheel of radius r on the circumference of the calorimeter, and supporting equal weights kk by means of frictionless pulleys. During an experiment the paddles inside the calorimeter were rotated by means of the hand-wheels at the top of the apparatus at such a speed as to keep the weights floating steadily, balancing the turning moment due to the friction of the paddles churning the water. If the sum of the weights is equal to W the work done against friction in n revolutions as shown by the counter will be 2lrrnW in mechanical units. The corresponding value of the heat generated is calculated in the usual way from the product of the thermal capacity M of the calorimeter and its contents, by the observed rise of temperature (t'-t") corrected for heat-loss. The ratio J = 27rrntiV/M (t'-t") gives the required value of the mechanical equivalent in terms of the units employed in the measurement.

As the result of this series of experiments Joule found that lb. of work in the latitude of Greenwich were required to raise the temperature of 1 lb. of water 1 ° at 6o° on the scale of his mercury thermometers. This agreed very closely with the value 772 under similar conditions obtained in his earlier experi ments in 1850, but disagreed with the value obtained by the elec tric method on the assumption that the B.A. unit of resistance correctly represented the absolute value of the ohm. The discrep ancy was subsequently explained by the discovery that the absolute value of the B.A. unit of resistance was about 1.3% too small as compared with the true ohm.

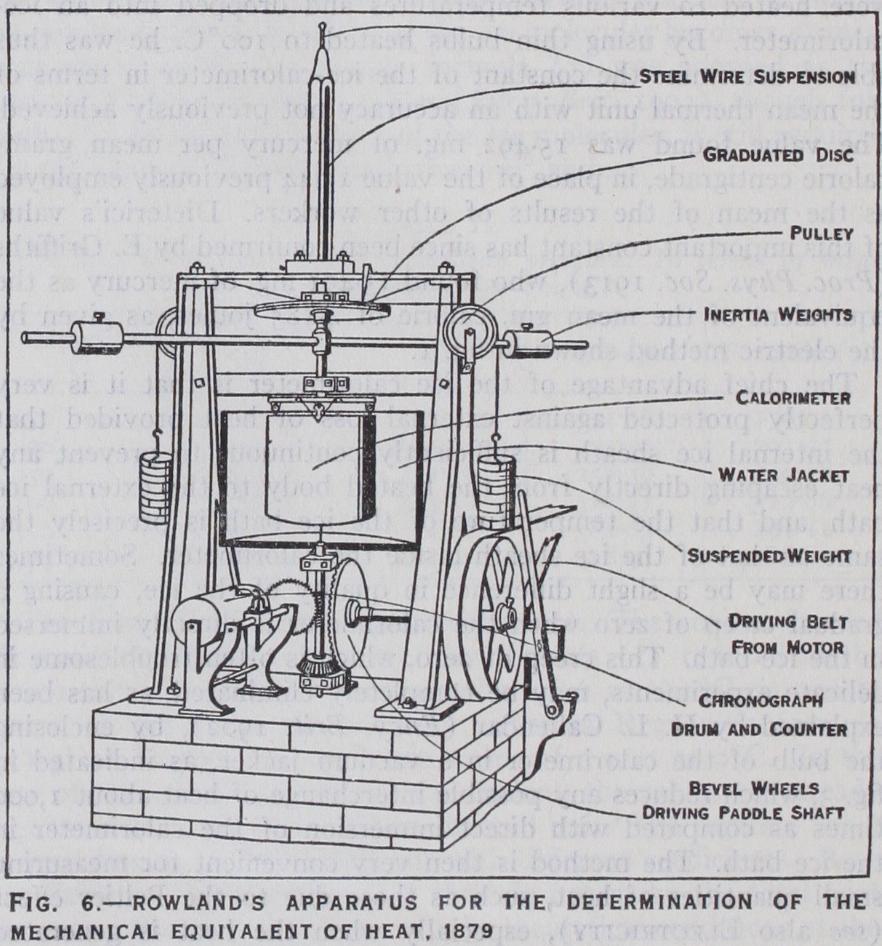

About the same time H. A. Rowland (Proc. Amer. Acad. xv. p.75, 1880) repeated the measurement of the mechanical equiva lent, employing the same method as Joule in 1878, but with many improvements in detail, as illustrated in fig. 6. His calorimeter was suspended by a steel wire, the torsion of which made the equilibrium stable, and was slightly larger and more compact than Joule's. To reduce the relative importance of the heat-loss, he found it necessary to secure a greater rate of heat-supply, about 17 times that employed by Joule. The paddles were mounted on a vertical spindle F, passing through a gland in the bottom of the calorimeter, and were driven through bevel gearing g by a belt from a petroleum motor running at a nearly constant speed. The greater part of the torque due to the friction of the paddles inside the calorimeter was balanced by the floating weights 0 and P, suspended by silk ribbons passing over pulleys and round the wheel kl. The small variations of torque with speed were balanced by the twist of the steel wire suspension, and were observed by a scale on the circumference of the wheel kl. The number of revolu tions of the paddles was recorded automatically on a chronograph drum driven by a worm gear from the spindle f. The rise of tem perature was recorded on the same sheet by an observer watching the thermometer and pressing a key at the moment when the mer cury passed each division of the scale. The paddles were made very light and rigid, in order to reduce their water-equivalent, and were arranged to give the greatest possible uniformity of torque and efficiency of stirring. The lower part of the calorimeter was surrounded by a water jacket at a definite temperature in order to protect it from draughts and to make the heat-loss consistent. The heat-loss at any temperature was estimated by observing the rate of rise of temperature in subsidiary experiments when the paddles were driven at a much slower rate than in the main series of observations. It was found possible to obtain reliable observa tions in this way over a range from 5° to 35°C. about 14 times greater than in Joule's experiments, owing to the greater rate of work supply. But some of the observations were vitiated by dep osition of dew on the calorimeter at the lower limit, and the heat loss at the upper limit was rendered somewhat uncertain by upward convection currents from the heated calorimeter, which could not be completely enclosed. That Rowland's calorimetric observations were more accurate than those of any previous ob server was clearly indicated by the fact that they conclusively demonstrated the diminution of the specific heat of water with rise of temperature from 5° to 3o°C., which had never been sus pected, and has since been confirmed with remarkable precision.

Rowland was the first to appreciate the importance of reducing results for the mechanical equivalent to the absolute scale of tern perature in place of the arbitrary scale given by a particular mer cury thermometer. He considered that the comparison of his mercury thermometers with the air thermometer was the most difficult part of the investigation, and estimated the limit of ac curacy at only 1 in 500 on this account ; especially as the ther mometers could not be compared under the actual conditions of the experiments, with the temperature rising at the rate of nearly 1°C. per minute, owing to the excessive lag of the air thermom eter and the time required for taking readings. Nevertheless, the probable accuracy of his result, namely, 4.179 joules per gm.cal. at 20°C., the middle point of his range, may be taken as at least I in 2,000, since it was only raised to 4.181 by an elaborate com parison of his thermometers with Paris standards by Day, and with the platinum thermometer by Griffiths. Some 20 years later his result at 20°C. was further confirmed by the continuous elec tric method already described, in terms of the standard ohm and the Clark standard cell. By that time the absolute value of the ohm was known to at least 1 in 5,000, but that of the Clark cell was more doubtful, and was accordingly determined by R. 0. King (Phil. Trans. 190 2) using a special form of electrodyna mometer which he set up for the purpose. The accuracy of this instrument has since been confirmed by Norman Shaw (Phil. Trans. 1915), who employed it without any alteration for a similar determination of the absolute value of the Weston standard cell. Including all known corrections for the values of the electric units since ascertained, the electric method gives 4.178 joules, agreeing closely with Rowland's uncorrected result for the absolute value of the gm.cal. C. at 20°C. The corresponding value for the mean gm.cal. o° to Ioo°C. would be 4.185 joules according to Table I. This also agrees very closely with the value 4.184 joules for the mean calorie as directly obtained by Reynolds and Moorby (Phil. Trans. 1897) with a Iooh.p. steam engine, using a Froude Reynolds brake, in which the water was heated from near o°C. to Ioo°C. This agreement may be regarded as confirming the variation of the specific heat of water as given by equation (6). It is usual, however, to take the round number 4.180 joules as the equivalent to the gm. calorie at 20°C., giving greater weight to Rowland's corrected result. A very accurate determination of the gm. calorie in joules has recently been made by Laby and Hercus (Phil. Trans. A. 1927) between 15° and 20° by a steady flow method, in which the work was directly measured in mechanical units. They give the value 4.1809 joules for the gm. calorie at 20°C., but it is uncertain how far the last figure may be regarded as significant.

For special methods commonly employed in the determination of the heats of combustion and calorific values of fuels, see article THERMOCHEMISTRY. For specific heats of gases and vapours, see articles HEAT, THERMODYNAMICS and VAPORIZATION. (H. L. C.)