Cambrian System

CAMBRIAN SYSTEM, in geology, is the name applied to the oldest group of rocks in which fossils have been found in any abundance. Organic remains have, indeed, been discovered in still older beds, but they are rare and obscure. The name was originally proposed by Sedgwick and, as used by him, it included the Lower Silurian of Murchison, which is now commonly recog nized as a separate system under the name Ordovician. Thus the Cambrian of the present day is the Lower Cambrian of Sedg wick. Other terms which have been used with approximately the same significance are Primordial Silurian and Taconic, the latter in America only. The original Taconic of Emmons has, however, proved to be a complex of various ages and the name has dropped out of use. Although the term Cambrian is now universally ac cepted, there are still differences of usage with regard to its precise limits. In England the Tremadoc beds, which in their fauna are intermediate between the Cambrian and the succeeding system, are usually included in the Cambrian; on the Continent the corresponding beds are placed in the Ordovician.

In general the Cambrian period was a quiet one. No violent crustal disturbances can be assigned to it and manifestations of volcanic activity are insignificant. Considerable changes of level are indicated by the nature of the sediments and by local discon tinuities, but these changes were not accompanied by folding. Even the most considerable gaps in the succession are usually not marked by any definite unconformity and have often been over looked till the examination of the included fossils showed that a part of the system was missing. In many areas, however, the beds have since undergone great earth-movements and the muds and sands of the period have been converted, as in Wales, into slates and quartzites. Where, as in Estonia, they have been little disturbed, they may remain nearly as soft as when laid down.

At one time it was imagined that the Cambrian faunas through out the world were more uniform in character than those of later periods. It was even supposed that there was a similar uniformity in the nature of the deposits and, in particular, a conspicuous deficiency in limestone. Hence it was argued that during the Cambrian period the ocean waters were more evenly spread over the globe than they have been since, and that climatic differences were less marked. Such views, however, can no longer be held.

So great are the differences between the Cambrian faunas of west ern America and of northern Europe that the real difficulty is not to distinguish between them but to correlate them ; and while limestone is absent from the Cambrian of Wales there are thou sands of feet of limestone in the Cambrian of the Canadian Rockies.

Life of the Period.

Although the Cambrian fauna is the ear liest of which we know more than traces, there is nothing prim itive about it. It is very varied and includes many different classes of animals. The Protozoa are represented by radiolaria and sponges, the Coelentera by corals, by the earliest graptolites and even by casts of such delicate forms as medusae. The Echino derma include crinoids, starfishes and cystideans. Annelids occur even in the oldest beds. Brachiopoda and Mollusca are locally numerous and various forms of Crustacea are found ; but by far the most varied and abundant group is the Trilobita (q.v.), which includes a great variety of forms, ranging from the small and simple Agnostus to the large and many-segmented Paradoxides.Classification.—Lithological divisions of a geological system have no more than a local value, and a grouping of the beds according to their fossil contents is much more widely applicable; but in the Cambrian there is nothing comparable, either in pre cision or in generality, with the graptolite zones of the Ordovician and Silurian or the ammonite zones of the Jurassic. It is true that many of the palaeontological zones established in Scandinavia can be recognized in Wales and even in Newfoundland, but in Western America and Eastern Asia the characteristic fossils of these zones are entirely absent. Even the broader palaeontolog ical subdivisions of northern Europe cannot there be distinguished.

In Europe three divisions have long been recognized, each char acterized by a special group of trilobites, after which it is named. These divisions are, in ascending order, the Olenellus series, the Paradoxides series, and the Olenus series. In this connection Olenellus and Olenus are used in a wide sense and must be under stood to include allied forms. Neither Olenellus nor Olenus in the stricter sense ranges throughout the series named after it. The Olenellus group of trilobites seems to have been world-wide in its distribution, but through the greater part of America, Asia and Australia Paradoxides and Olenus and their allies are un known, although the deposits of the period during which they lived are present. In America Olenoides series and Dikeloceph alus series would be more appropriate terms ; but it is not yet pos sible to establish any subdivision of the Cambrian system into series of universal applicability. We use such terms as Lower, Middle and Upper Cambrian: but it would be rash to assume, e.g., that the Middle Cambrian of the Rockies corresponds in more than a general way with that of Wales or even of New Brunswick. Atlantic and Pacific Faunas.—The Cambrian fauna of Wales is very like that of Scandinavia, many of the species being iden tical, and a similar fauna is also found in the extreme east of North America. But the Cambrian fossils of the north of Scot land are quite different and closely resemble those from the Ap palachian region of Canada and the United States. There are, in fact, two distinct faunas which lived, no doubt, in separate seas. Between them lay a barrier of land which stretched from the Appalachian plateau across the Atlantic into Scotland.

In the Western Cordillera of Canada and the United States there is another abundant Cambrian fauna, very different from that of Wales but with a much closer affinity to that of the Ap palachian area. A very similar fauna is found in China, and the Cambrian faunas of India and Australia are also closely related. It seems, therefore, that even in Cambrian times there was an Atlantic and a Pacific occupying part of their present sites and in some directions spreading far beyond.

It is not possible here to do more than indicate a few of the differences between the faunas of the two oceans. In the Atlantic fauna Paradoxides, Olenus, Peltura, Parabolina, Leptoplastus and several other allied genera play an important part ; in the Pacific fauna they are unknown, though one or two species allied to Olenus have been found. The Pacific fauna includes a whole series of genera which are not found in the Atlantic area. There is a much greater variety of forms belonging to the same family as Olenellus (the Mesonacidae) ; but perhaps the most striking feature is the number of large-tailed genera, such as Asaphiscus and Ogygopsis, which closely resemble the Asaphids characteristic of the European Ordovician. To a certain extent the place of Paradoxides is taken by Olenoides and its allies, the place of Olenus by Dikelocephalus and similar genera. The latter are not altogether absent from the Atlantic fauna but are much less numerous and varied.

The Atlantic fauna of the Cambrian period stretched from the mouth of the St. Lawrence on the west to the Lena on the east. The western limit is sharply defined, for while the Cambrian of eastern Newfoundland, New Brunswick, and eastern Massachu setts belongs to the Atlantic type, the corresponding beds of western Newfoundland and the Appalachian region are of Pa cific type. Northwards the Atlantic fauna did not reach the Scottish Highlands, for there we find the fauna of the Appalachian sea. In eastern Europe, however, it extended into Vaigach island and farther east it stretched beyond the present continent of Asia to the New Siberian islands. Southwards it reached the Mediter ranean region, for the Cambrian of the Spanish peninsula, Sar dinia and the Dead sea belongs to this type.

The whole of the area included within these limits was not a single broad expanse of sea. The Cambrian fauna of Sardinia is very different from that of Scandinavia. Probably an incomplete land-barrier lay between, but the differences may be partly due to differences of temperature, depth or other conditions. In some cases an apparent difference between the faunas of two regions has been brought about by the absence in one of them of the deposits belonging to a part of the period.

On the western side of the present Pacific the Pacific fauna of the Cambrian period has been found in Manchuria, China, Indo China, the central Himalayas, the Indus Salt range, Australia and Tasmania. On the eastern side it is found in the Western Cordil lera of North America, in the Appalachian region and in the north of Scotland. Much of the interior of the United States was also covered by seas for some part of the period. The Appalachian Cambrian, for example, seems to have been laid down in a com paratively narrow gulf which north-eastward stretched as far as Scotland and south-westward entered the open ocean. The Cordil leran Cambrian is believed to have been deposited in a trough run ning along the line of the present Cordillera and separated from the ocean by a land-mass which occupied the site of the Cascade range. This trough is supposed to have been connected with an Arctic ocean in the north and an open Pacific towards the south. For the greater part of the period the Appalachian gulf and the Cordilleran trough were separated by land occupying most of the interior of Canada and the United States, but towards the close much of this area was covered by the sea. The Cambrian faunas of China, India and Australia, although all of Pacific type, show sufficient individuality to suggest that the seas in which they lived were not always in free communication.

Europe.—The principal Cambrian areas of Europe are in the north-west of Scotland, in Wales and the neighbouring counties of England, in Scandinavia, Estonia, Bohemia, the Spanish penin sula and Sardinia. Beds also occur in the Ardennes, Brittany, the Montagne Noire S. France, and in Germany and Poland.

It has already been remarked that the Cambrian of the north of Scotland belongs to the Pacific type. The rocks are chiefly sandstones and dolomitic limestones, the former predominating in the lower part of the series and the latter in the upper part. Olenellus occurs in the Fucoid beds, towards the middle of the series, but the Durness limestone, which forms the upper part, contains a very different fauna. Trilobites occur, but the most striking feature is the dominance of cephalopods and gasteropods, most of the species being unknown elsewhere in Britain but occur ring in Canada. Comparison with that area suggests that the limestone belongs to the Upper Cambrian. Palaeontologically there is no trace of the Middle Cambrian, but as yet no break has been detected in the succession.

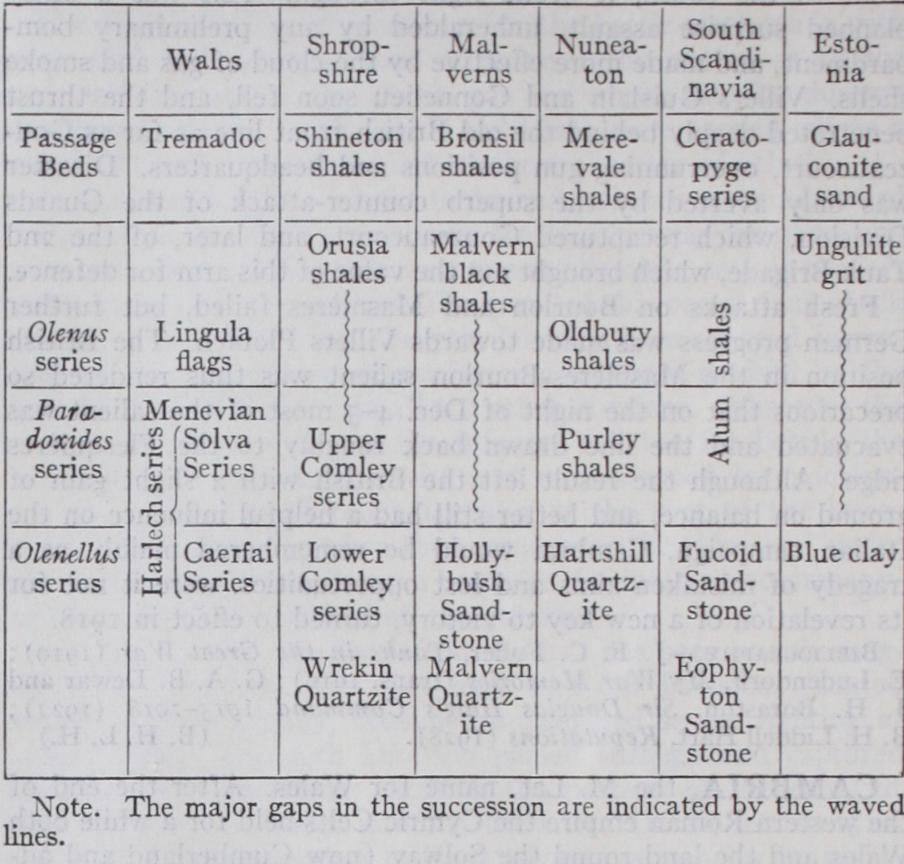

The accompanying table gives many of the more important local names of subdivisions used in various parts of northern Europe and shows their approximate correlation. It should be remembered that the greater part of the "Passage Beds" of this table is placed by Continental geologists in the Ordovician. The Dictyonema fiabelliforme zone, which in Wales occurs near the base of the Tremadoc, is usually taken as the line of demarcation.

In the strip of northern Europe which includes the areas men tioned in the table, the Cambrian attains its greatest thickness in Wales, where it has been estimated to exceed 12,000 feet. Upon the Welsh borders the thickness is much reduced, partly because there was less deposition throughout the period and partly because there is a considerable gap in the succession. Probably there was land here during the middle of the period and shallow water dur ing the remainder. At Nuneaton, in Warwickshire, no break in deposition has been detected, but the total thickness is still much less than in Wales.

In Scandinavia the Alum shales, which are black shales with dark calcareous nodules and bands, are only some roof t. thick, but the succession is complete, except that there has been a cer tain amount of submarine erosion at the top of the shales. In Estonia, along the south shore of the Gulf of Finland, the total thickness of the Cambrian is not more than i oof t., though borings at Reval and Leningrad show as much as 60o feet. But the small thickness here is certainly due in part to the total absence of the Paradoxides series and the imperfect development of the Olenus series. The Ungulite grit is placed in the latter, but Olenus and its congeners are absent. In spite of this great gap there is no unconformity, and the gap is indicated chiefly by the fact that the base of this grit contains fragments of the underlying beds.

In Bohemia the Cambrian consists of sandstones and conglom erates below, with a few obscure fossils, followed by greenish thick-bedded slates containing an abundant fauna. Trilobites pre dominate, and amongst them are species of Paradoxides. The Olenellus series may perhaps be represented by the unf ossilif erous sandstones, but the Olenus series is absent, for the Paradoxides beds are followed immediately by the Ordovician. Even in the Paradoxides series most of the fossils are so distinct from those of Scandinavia as to suggest the possibility of an intervening land barrier. The occurrence of a Tremadoc fauna near Hof, Bavaria, points to an extension of the sea at the close of the period.

In southern Europe Cambrian beds are found in the Montagne Noire, the Spanish provinces of Leon, Asturias, Aragon and Seville, the Portuguese province of Alemtejo, and in Sardinia. In all these areas Paradoxides occurs, and the discovery of that genus near the Dead sea seems to indicate that in Middle Cam brian times a southern sea extended as far as Palestine. Neither Olenellus nor Olenus has been found, but in Portugal and Sardinia there is a lower fauna suggestive of the Olenellus series. The wide distribution of Archaeocyathus limestones in southern Europe is noteworthy.

Asia.—Cambrian beds cover a wide area in Siberia and in Man churia and northern China. They have also been found in Yunnan and Indo-China. In the central Himalayas there is an interesting development in Spiti, while south of the Himalayas a different type is found in the Salt range of the Indus. The occurrence of Paradoxides and other Cambrian fossils near the Dead sea, already referred to, suggests that the series of sandstones so widely spread in south-western Asia and northern Africa may include deposits of Cambrian age. So far as the fauna is concerned the Cambrian of the Dead sea and of Siberia belong to the Atlantic type, while in the remaining areas it is of Pacific type.

In Siberia the Cambrian covers a wide area extending from the Yenisei to the Lena. It has been found as far south as 56° N. Lat., and as far north as the New Siberian islands. In general the beds are nearly horizontal and consist of sandstones, shales and limestones. Much of it may certainly be referred to the Para doxides series, though Paradoxides itself has not been recorded, but it is probable that the lower beds belong to the Olenellus series. In this lower division there is a considerable development of Archaeocyathus limestones containing Dorypyge.

In Manchuria and northern China, also, the Cambrian strata are in general horizontal, but along certain lines there has been very considerable disturbance, accompanied even by overthrust ing. Two main divisions are recognized, the Man-t'o shale below and the Kiu-Lung group above. These are approximately the equivalents of the Lower Sinian and the Middle Sinian of Richt hofen, who first described them. His Upper Sinian is Ordovician. The Man-t'o series has a thickness of 300-5ooft., consisting chiefly of red shale with beds of sandstone and thin layers of limestone. Fossils are not abundant but Lower Cambrian and Middle Cam brian forms have been found. Amongst them is the trilobite Redlichia, a genus which has a wide distribution in Asia. It seems to belong to the same family as Olenellus although, unlike the other genera of that family, it has a distinct facial suture. It oc curs chiefly in the Lower Cambrian but extends upwards into beds which are referred to the Middle Cambrian. The Kiu-Lung group, about i,000ft. in thickness, consists of shales and lime stones, the shales being green in colour. The fauna is very rich and includes a number of trilobite genera which have not yet been found elsewhere. There is, however, enough resemblance to the fauna of western North America to indicate that the lower part of the group belongs to the Middle Cambrian and the upper part to the Upper Cambrian.

In Yunnan and in the northern part of Indo-China the Cam brian beds are greatly disturbed but nevertheless have yielded an abundant fauna. In general it is very like that of northern China but includes one or two peculiar genera.

The Cambrian of Spiti consists of several thousand feet of slates and quartzites with thin bands of dolomite in the upper thousand feet. It is from this upper portion that fossils have been obtained. Redlichia has been found, and in the higher f os siliferous bands there are one or two forms which seem to be allied to Olenus, but no true Olenus has been discovered. The majority of the fossils seem to belong to the Middle Cambrian and have Pacific rather than Atlantic affinities.

The beds which are referred to the Cambrian in the Salt range consist chiefly of sandstone and shale with a very remarkable de posit of salt in the lower part of the series. Cambrian fossils occur in the Neobolus shales, which lie in the upper half of the series. Amongst them are Redlichia and other trilobites, brachio pods and mollusca.

Australia and Tasmania.

Cambrian beds occupy a wide area in Northern Territory, where they consist largely of lime stones and attain a thickness of perhaps 7,000 feet. Thick sheets of basic lava below seem to belong to the period. In South Aus tralia the system is found between Lake Eyre and Kangaroo island, and stretches across the Barrier range into New South Wales. In this southern area one of the most remarkable features is the presence of glacial deposits, fully I,000ft. thick, towards the mid dle of the system. Higher up is a great development of Archaeo cyathus limestones. The fauna of the Australian Cambrian is dis tinctly Pacific in type, including Redlichia and large-tailed trilo bites of Asaphid aspect. In Tasmania the Cambrian beds have yielded well-preserved casts of Dikelocephalus.North America.—In the eastern part of Newfoundland, in New Brunswick and Cape Breton, and in the eastern part of Massachusetts the Cambrian is of Atlantic type. Even the indi vidual zones which have been distinguished in Wales or Scandi navia may sometimes be recognized. On the whole recent re searches tend rather to reduce than to increase the differences which have been observed. The Protolenus zone, for example, with its peculiar fauna, which was first recognized in New Bruns wick, has since been discovered in Shropshire.

With the exception of these most eastern parts the American Cambrian is of Pacific type, the system attaining its greatest de velopment in the Appalachian and Cordilleran troughs. The in tervening space is largely concealed by later beds and where the Cambrian is exposed the Lower and Middle divisions are often, but not always, absent.

In the Appalachian trough the deposits are thickest and most continuous in the south. They become more sandy and pebbly towards the east, that is, towards the land-barrier which separated the trough from the Cambrian Atlantic. The Middle Cambrian is poorly represented in the north of the region and it seems that at that time the sea had retreated towards the south. But in Upper Cambrian times it spread northward again, and also overflowed the land-mass that separated it from the Cordilleran trough.

The Cordilleran trough contains perhaps the finest development of the system in the world, and certainly it has yielded the most abundant fauna. The beds are often very little disturbed or al tered and consequently the fossils are remarkably well preserved. A whole series of genera have been described which are as yet un known elsewhere. Mt. Stephen in the Canadian Rockies is per haps the most famous of all the fossil localities, but very fine sec tions are also to be seen in California, Utah and Nevada. Towards the west the deposits become sandy, indicating the existence of a land-mass in that direction, which has been called Cascadia. It included the site of the present Cascade range.

The terminology of the North American Cambrian has varied greatly and it may be convenient to mention here the names that have been applied at different times to the major subdivisions. The Lower Cambrian has sometimes been called the Georgian, sometimes the Waucoban; the Middle Cambrian is often named the Acadian ; the Upper Cambrian has been called the Pots damian, the Saratogan or the Croixan. The name Ozarkian has been applied to the passage beds between the Cambrian and the Ordovician, but Ulrich, who first proposed the name, considers the Ozarkian to form a separate system, which has not been definitely identified outside America.

South America.—Cambrian beds have been found in Argen tina and Bolivia, but are still very imperfectly known. It is, in deed, scarcely possible to say from the recorded fauna whether it is more closely allied to the Atlantic or to the Pacific type. The Argentine fossils suggest the Middle Cambrian, but the occur rence of Peltura in Bolivia points to the upper division of the system and to an Atlantic connection.