Canada

CANADA. The Dominion of Canada comprises the northern half of the continent of North America and its adjacent islands, excepting Alaska, which belongs to the United States, and New foundland, which is a separate dominion of the British empire. The north-eastern coast of Labrador belongs to Newfoundland. Its boundary on the south is the parallel of latitude 49°, between the Pacific Ocean and Lake-of-the-Woods, then a chain of small lakes and rivers eastward to the mouth of Pigeon river on the north-west side of Lake Superior, and the Great Lakes with their connecting rivers to Cornwall, on the St. Lawrence. From this eastward to the state of Maine the boundary is an artificial line nearly corresponding to latitude ; then an irregular line partly determined by watersheds and rivers divides Canada from Maine, coming out on the Bay of Fundy. The western boundary is the Pacific on the south, an irregular line a few miles inland from the coast along the "pan handle" of Alaska to Mount St. Elias, and the meridian of to the Arctic Ocean. For much additional information concerning Canada, see BRITISH EMPIRE.

Physical Geography.

In spite of these restrictions of its natural coast line on both the Atlantic and the Pacific, Canada is admirably provided with harbours on both oceans. The Gulf of St. Lawrence with its much indented shores and the coast of Nova Scotia and New Brunswick supply endless harbours, the northern ones closed by ice in the winter, but the southern ones open all the year round ; and on the Pacific British Columbia is deeply fringed with islands and fjords with well-sheltered harbours every where, in strong contrast with the unbroken shore of the United States to the south. The long stretches of sheltered navigation from the Straits of Belle Isle north of Newfoundland to Quebec, and for 600 m. on the British Columbian coast, are of great ad vantage for the coasting trade. To the North Hudson Bay, an in land sea 85o m. long from north to south and 600 m. wide, with its outlet Hudson Strait, has long been navigated by trading ships and whalers, and may become an outlet for the wheat of western Canada, though closed by ice except for four months in the sum mer. Of the nine provinces of Canada only two have no coast line on salt water, Alberta and Saskatchewan. Ontario and Mani toba have a seaboard only on Hudson Bay, where Churchill Har bour on the west side may become an important grain port. What Ontario lacks in salt water navigation is, however, made up by the busy traffic of the Great Lakes.More than half Canada's surface slopes gently inwards towards the shallow Hudson Bay, with higher margins to the south-east and south-west. In the main it is a broad trough, wider towards the north than towards the south and unsymmetrical, Hudson Bay occupying much of its north-eastern part, while to the west broad plains rise gradually to the foot-hills of the Rocky Mountains.

Geology.

The mountain structures originated in three great orogenic periods, the earliest in the Archaean, the second at the end of the Palaeozoic and the third at the end of the Mesozoic. The Archaean mountain chains, which enclosed the present region of Hudson Bay, are so ancient that they had already been worn down almost to a plain before the early Palaeozoic sediments were laid down. This ruling geological and physical feature of the North American continent has been named the "Canadian Shield." Round it the Palaeozoic sands and clays, largely derived from its own waste, were deposited as nearly horizontal beds, in many places still almost undisturbed. Later the sediments lying to the south east of this "protaxis," or nucleus of the continent, were pushed against its edge and raised into the Appalachian chain of moun tains. The Mesozoic sediments were almost entirely laid down to the west and south-west of the protaxis, upon the flat-lying Pal aeozoic rocks, and in the prairie region they are still almost hor izontal; but in the Cordillera they have been thrust up into the series of mountain chains characterizing the Pacific coast region. The youngest of these mountain chains is naturally the highest, and the oldest one in most places no longer rises to heights deserv ing the name of mountains. Owing to this unsymmetric develop ment of North America the main structural watershed is towards its western side, on the south coinciding with the Rocky Moun tains proper, but to the northward falling back to ranges situated farther west in the same mountain region. The central area of Can ada is drained towards Hudson Bay, but the two largest Canadian rivers have separate watersheds, the Mackenzie flowing north west to the Arctic Ocean and the St. Lawrence north-east towards the Atlantic, the one to the south-west and the other to the south east of the Archaean protaxis. While these ancient events shaped the topography in a broad way its final development took place during the glacial period, when the loose materials were scoured from some regions and spread out as boulder clay, or piled up as moraines in others; and the original water-ways were blocked in many places. The retreat of the ice left Canada much in its present condition and the region has a very youthful topography with innumerable lakes and waterfalls as evidence that the rivers have not long been at work.

Lakes and Rivers.

As a result of the geological causes just mentioned many parts of Canada are lavishly strewn with lakes of all sizes, from bodies of water hundreds of miles long and a thousand feet deep to ponds lost to sight in the forest. The largest and most thickly strewn lakes occur within five hundred or a thousand miles of Hudson Bay, and belong to the Archaean pro taxis or project beyond its edges into the Palaeozoic sedimentary rocks which lean against it. The most famous are those of the St. Lawrence system, which form part of the southern boundary of Canada and are shared with the United States; but many others have the right to be called "Great Lakes" from their magnitude. There are nine others which have a length of more than i oo m., and 35 which are more than 5o m. long. Within the Archaean protaxis they are of the most varied shapes, since they represent merely portions of the irregular surface inundated by some mo rainic dam at the lowest point. They often contain islands, some times even thousands in number, as in Georgian Bay and Lake of-the-Woods.In the Cordilleran region on the other hand the lakes are long, narrow and deep, in reality sections of mountain valleys occupied by fresh water, just as the fjords of the adjoining coast are valleys occupied by the sea. The smaller lakes are often rimmed with marshes and are slowly filling up with vegetable matter, ultimately becoming peat bogs, the muskegs of the Indian. Most of Canada is so well watered that the lakes have outlets and are kept fresh, but there are a few small lakes in southern Saskatchewan, e.g., the Quill and Old Wives lakes, in regions arid enough to require no outlets. In such cases the waters are alkaline, and contain various salts in solution which are deposited as a white rim round the basin towards the end of the summer when the amount of water has been greatly reduced by evaporation. It is interesting to find maritime plants, such as the samphire, growing on their shores a thousand miles from the sea and more than a thousand feet above it. In many cases the lakes of Canada simply spill over at the lowest point from one basin into the next below, so that canoe navigation may be carried on for hundreds of miles, with here and there a waterfall or rapid requiring a portage.

The river systems are in many cases complex and tortuous, and very often the successive connecting links between the lakes re ceive different names, well illustrated by the St. Lawrence, which may be said to begin as Nipigon river and to take the names St.. Mary's, St. Clair, Detroit and Niagara, before finally flowing from Lake Ontario to the sea under its proper name. As these lakes are great reservoirs and settling basins, the rivers which empty them are unusually steady in level and contain clear water. The St. Lawrence varies only a few feet in the year and always has pel lucid bluish-green water, while the Mississippi, whose tributaries begin only a short distance south of the Great Lakes, varies 40 ft. or more between high- and low-water and is loaded with mud. The St. Lawrence has provided the main artery of exploration and with its canals past rapids and between lakes serves as a great highway of trade between the interior of the continent and the seaports of Montreal and Quebec. It is probable that politically Canada would have followed the course of the States to the south but for the planting of a French colony with widely extended trading posts along the easily ascended channel of the St. Law rence and the Great Lakes, so that this river was the ultimate bond of union between Canada and the empire.

North of the divide between the St. Lawrence system and Hud son Bay there are many large rivers converging on that inland sea, such as Whale river, Big river, East Main, Rupert and Nottaway rivers coming in from northern Quebec ; Moose and Albany rivers with important tributaries from northern Ontario ; and Severn, Nelson and Churchill rivers from the south-west. They are rapid and shallow, but the largest of them, Nelson river, drains the great Manitoban lakes, Winnipeg, Winnipegosis and Manitoba, which are frequented by steamers, and receive the waters of Lake-of the-Woods, Lake Seul and many others emptying into Winnipeg river from Ontario ; of Red river coming in from the United States to the south; and of the southern parts of the Rocky Mountains and the western prairie provinces drained by the great Saskatchewan river.

The northern part of Alberta and Saskatchewan and much of northern British Columbia are drained through the Athabasca and Peace rivers, first north-eastwards towards Athabasca Lake, then north through Slave river to Great Slave Lake, and finally north west through Mackenzie river to the Arctic Ocean. If measured to the head of Peace river the Mackenzie has a length of more than 2,000 m., and it provides more than i,000 m. of navigation for stern-wheel steamers, serving the northern fur-trading posts.

Second among the great north-western rivers is the Yukon, which begins its course about 18 m. from tide-water on an arm of the Pacific, 2,800 ft. above the sea and just within the Canadian border. It flows first to the north, then to the north-west, passing out of the Yukon territory into Alaska, and ending in Bering Sea, 2,000 m. from its head-waters. The rest of the rivers flowing into the Pacific pass through British Columbia and are much shorter. The Columbia is the largest, but after flowing north-west and then south for about 400 m., it passes into the United States. The Fraser, next in size but farther north, follows a similar course, entering the sea at Vancouver; while the Skeena and Stikine in northern British Columbia are much shorter and smaller, owing to the encroachments of Peace and Liard rivers, tributaries of the Nelson, on the Cordilleran territory. In most cases these rivers reach the coast through deep valleys or profound canyons, and the transcontinental railways find their way beside them, the Canadian Pacific following at first tributaries of the Columbia near its great bend, and afterwards Thompson river and the Fraser; while the Canadian National makes use of the valley of the Skeena and its tributaries.

The divide between the rivers flowing west and those flowing east and north is very sharp in the southern Rocky Mountains, but there are two lakes, the Committee's Punch Bowl and the Fortress Lake, right astride of it, sending their waters both east and west; and the melting snows of the Columbia ice-field drain in three directions into tributaries of the Columbia, the Saskatch ewan and the Athabasca, so that they are distributed between the Pacific, the Atlantic (Hudson Bay) and the Arctic Oceans. The divide between the St. Lawrence and Hudson Bay in eastern Canada is flat and boggy instead of being a lofty range of moun tains.

As most of the Canadian rivers have waterfalls on their courses, they are of much importance as sources of power. The St. Law rence system, for instance, generates many thousand horse-power at Sault Ste. Marie, Niagara and the Lachine rapids. All the larger cities of Canada make use of hydro-electric power, and many enterprises of the kind have been carried out in eastern Canada, especially in Quebec.

The Archaean Protaxis.

The broad geological and geograph ical relationships of the country have already been outlined, but the more important sub-divisions may now be taken up with more detail, and for that purpose five areas may be distinguished, much the largest being the Archaean protaxis, covering 1,8 25,00o square m. It includes Labrador and most of Quebec on the east, north ern Ontario on the south; and the western boundary runs from Lake-of-the-Woods north-west to the Arctic Ocean near the mouth of Mackenzie river. The southern parts of the Arctic islands, especially Banksland, belong to it also. This vast area, shaped like a broad-limbed V or U, with Hudson Bay in the centre, is made up chiefly of Laurentian gneiss and granite ; but scattered through it are important stretches of Keewatin, Timiskaming and Huronian rocks intricately folded as synclines in the gneiss. The Keewatin, Timiskaming and Huronian, consisting of greenstones, schists and more or less metamorphosed sedimentary rocks, are of special interest for their ore deposits, which include most of the important metals, particularly nickel, copper, silver and gold. The southern portion of the protaxis is opened up by railways, but the far greater northern part is known only along the lakes and rivers which are navigable by canoe. Though once consisting of great mountain ranges there are now no lofty elevations in the region except along the Atlantic border in Labrador, where summits of the Nachvak Mountains reach 5,500 ft. In other parts the surface is hilly, the harder rocks, rising as rounded knobs, or ridges, while the softer parts form valleys generally floored with lakes.From the summit of any of the higher hills one sees that the region is really a somewhat dissected plain, for all the hills rise to about the same level with a uniform skyline at the horizon. The Archaean protaxis is sometimes spoken of as a plateau, but prob ably half of it falls below i ,000 ft. The lowland part extends from to soo m. round the shore of Hudson Bay, and reaches south west to the edge of the Palaeozoic rocks on Lake Winnipeg. Out wards from the bay the level rises slowly to an average of about 1,500 ft., but seldom reaches 2,000 ft. except on the eastern and southern coasts of Labrador. In most parts the Laurentian hills are bare roches moutonnees scoured by the glaciers of the Ice age, but a broad band of clay land extends across northern Quebec and Ontario just north of the divide. The edges of the protaxis are in general its highest parts, and the rivers flowing outwards often have a descent of several hundred feet in a few miles towards the Great Lakes, the St. Lawrence or the Atlantic, and in some cases they have cut back deep gorges or canyons into the tableland. The waterfalls are utilized at many points to work up into wood pulp the forests of spruce which cover much of Labrador, Quebec and Ontario.

As one advances northward the timber grows smaller and in cludes fewer species of trees, and finally the timber line is reached near Churchill on the west coast of Hudson Bay and somewhat farther south on the Labrador side. Beyond this are the "barren grounds" on which herds of caribou (reindeer) and musk ox pas ture, migrating from north to south according to the season. There are no permanent ice sheets known on the mainland of north eastern Canada, but some of the larger islands to the north of Hudson Bay and Straits are partially covered with glaciers on their higher points. Unless there are mineral resources, the bar ren grounds can never support a white population and have little to tempt even the Indian or Eskimo, who visit it in summer to hunt the deer in their migrations.

The Acadian Region.

The "maritime provinces" of eastern Canada, including Nova Scotia, New Brunswick and Prince Ed ward Island, may be considered together; and to these provinces may be added, from a physical point of view, the analogous south eastern part of Quebec—the entire area being designated the Aca dian region. Taken as a whole, this eastern part of Canada, with a very irregular and extended coast-line on the Gulf of St. Law rence and the Atlantic, may be regarded as a northern continua tion of the Appalachian mountain system that runs parallel to the Atlantic coast of the United States. The rocks underlying it have been subjected to successive foldings and crumplings by forces acting chiefly from the direction of the Atlantic Ocean, with alternating prolonged periods of waste and denudation. The main axis of disturbance and the highest remaining land runs through the south-eastern part of Quebec, forming the Notre Dame Moun tains, and terminates in the Gaspe peninsula as the Shickshock Mountains, some of which rise above 4,00o ft.The province of New Brunswick exhibits approximately par allel but subordinate ridges, with wide intervening areas of nearly flat Silurian and Carboniferous rocks. The peninsula of Nova Scotia, connected by a narrow neck with New Brunswick, is formed by still another system of parallel ridges, deeply fretted on all sides by bays and harbours. Valuable coal-fields occur in Cape Breton and other parts of the province. Gypsum is quarried on a large scale in both provinces. Asbestos is the principal min eral product of that part of Quebec included in the region now under consideration. Extensive tracts of good arable land exist in many parts of the Acadian region. Its surface was originally al most entirely wooded, and the products of the forest continue to hold a prominent place. Prince Edward Island, the smallest prov ince of Canada, is low and undulating, based on Permo-Carbon iferous and Triassic rocks affording a red and very fertile soil, much of which is under cultivation.

The St. Lawrence Plain.

As the St. Lawrence invited the earliest settlers to Canada and gave the easiest communication with the Old World, it is not surprising to find the wealthiest and most populous part of the country on its shores and near the Great Lakes to which it leads ; and this early development was greatly helped by the flat and fertile plain which follows it inland for over 600 m. from the city of Quebec to Lake Huron. This affords the largest stretch of arable land in eastern Canada, in cluding the southern parts of Ontario and Quebec with an area of some 38,00o sq. m. The whole region is underlain by nearly hori zontal and undisturbed rocks of the Palaeozoic from the Devonian downward. Superimposed on these rocks are Pleistocene boulder clay, and clay and sand deposited in post-glacial lakes or an ex tension of the Gulf of St. Lawrence. Though petroleum and salt occur in the south-west peninsula of Ontario, metalliferous de posits are wanting, and the real wealth of this district lies in its soil and climate, which permit the growth of all the products of temperate regions. To the north the Laurentian plateau rises di rectly from the upper Great Lakes; so that the fertile lands of the east with their numerous cities and largely-developed manufac tures were at one time cut off by a rocky and forest-covered Archaean region from the far more extensive farm lands of the west. The development of mines and the spread of settlement on the clay belt have now filled the gap between east and west.

The Interior Continental Plain.

Passing westward by rail from the forest-covered Archaean with its rugged granite hills, the flat prairie of Manitoba with its rich grasses and multitude of flowers comes as a very striking contrast, introducing the Inte rior Continental plain in its most typical development. This great plain runs north-westward between the border of the Archaean protaxis and the Rocky Mountains, including the southern parts of Manitoba and Saskatchewan and most of Alberta. At the inter national boundary in latitude 49° it is Boo m. wide, but in lati tude 56° it has narrowed to 400 m. in width, and to the north of latitude 62° it is still narrower and somewhat interrupted, but preserves its main physical features to the Arctic Ocean about the mouth of the Mackenzie. Most of the plains are underlain by Cretaceous and early Tertiary shales and sandstones lying nearly unaltered and undisturbed although now raised far above sea-level, particularly along the border of the Rocky Mountains where they were thrust up into foot-hills when the range itself was raised. Coal and lignite are the principal economic minerals met with in this central plain, though natural gas occurs and is greatly used. and there are important oilwells in the southern foothill region. Its chief value lies in its vast tracts of fertile soil suitable for growing wheat. The very flat and rich prairie near Winnipeg is .the former bed of the glacial Lake Agassiz; but most of the prairie to the west is of a gently rolling character and there are two rather abrupt breaks in the plain, the most westerly one receiving the name of the Missouri Coteau. The first step represents a rise to 1,60o ft., and the second to 3,00o ft. on an average. In so flat a country elevation of a few hundred feet is remarkable and is called a mountain, so that Manitoba has its Duck and Riding mountains. The treeless part of the plains, the prairie proper, has a triangular shape with an area twice as large as that of Great Britain. North of the Saskatchewan river groves of trees begin, and somewhat farther north the plains are generally wooded, because of the slightly more humid climate. It has been proved, however, that trees if protected will grow well on the prairie, as may be seen around the older farmsteads.

The Cordilleran Belt.

The Rocky Mountain region as a whole, best named the Cordillera or Cordilleran belt, includes several parallel ranges of mountains of different structures and ages, the eastern one constituting the Rocky Mountains proper. The Cordillera is 400 m. wide and covers towards the south al most all of British Columbia and a strip of Alberta east of the watershed, and towards the north forms the whole of the Yukon Territory. Two principal mountain axes form its ruling features— the Rocky Mountains proper, above referred to, and the Coast Ranges. Between them are many other ranges shorter and less regular in trend, such as the Selkirk Mountains, the Gold Ranges, and the Cariboo Mountains. There is also in the southern inland region an interior plateau, once probably a peneplain, but now ele vated and greatly dissected by river valleys, which extends north westward for 500 m. with a width of about i oo m. and affords the largest areas of arable and pasture land in British Columbia. Similar wide tracts of less broken country occur in northern Brit ish Columbia and to some extent in the Yukon Territory, where wide valleys and rolling hills alternate with short mountain ranges of no great altitude. The Pacific border of the coast range of British Columbia is ragged with fjords and channels, where large steamers may go 50 or ioo m. inland between mountain walls as on the coast of Norway; and there is also a bordering mountain system partly submerged forming Vancouver Island and the Queen Charlotte Islands.The highest mountains of the Cordillera in Canada are near the southern end of the boundary separating Alaska from the Yukon Territory, the meridian of i45° and they include Mount Logan (19,85o ft.) and Mount St. Elias (i 8,000 ft.), while the highest peak in North America, Mount McKinley (20,000 ft.) is not far to the north-west in Alaska. Near the height of land between British Columbia and Alberta there are many peaks which rise from i o,000 to i 2,000 ft. above sea-level, the highest being Mount Robson (12,972 ft.). The next range to the east, the Selkirks, has summits that reach r i,000 ft. or over, while the Coast Ranges sometimes reach 13,00o ft. The snow line in the south is from to 9,00o ft. above sea-level, being lower on the Pacific side where the heaviest snowfall comes in winter than on the drier north-eastern side. It gradually sinks as one advances north-west, reaching only 3,00o ft. on the Alaskan coast. The Rockies and Selkirks support hundreds of glaciers, mostly not very large, but some having i oo sq.m. of snowfield.

All the glaciers are now in retreat, with old tree-covered mo raines, hundreds or thousands of feet lower down the valley. The timber line is at about 7,500 ft. in southern British Columbia and 4,000 ft. in the interior of the Yukon Territory. On the westward slopes, especially of the Selkirks and Coast Ranges, vegetation is almost tropical in its density and luxuriance, the giant cedar and the Douglas fir sometimes having diameters of i o ft. or more and rising to the height of 25o ft. On the eastern flanks of the ranges the forest is much thinner, and on the interior plateau and in many of the valleys largely gives way to open grass land. The Coast Range was formed by a great upwelling of granite and diorite as batholiths along the margin of the continent in the Jurassic. The Rocky Mountains were raised after the close of the Cretaceous by tremendous thrusts from the Pacific side, crumpling and fold ing the ancient sedimentary rocks, and faulting them along over turned folds. The outer ranges in Alberta have usually the form of tilted blocks with a steep cliff towards the north-east and a gentler slope, corresponding to the dip of the beds, towards the south-west. Near the centre of the range there are broader fold ings, carved into castle and cathedral shapes. The most easterly range was pushed 7 m. out upon the prairies.

In the Rocky Mountains proper no ore deposits are known, but in the Cretaceous synclines which they enclose, valuable coal basins exist. The coking coals of the Fernie region supply the fuel of the great metal mining districts of the Kootenays in British Co lumbia, and of Montana and other states to the south. In the Coast and Gold Ranges there are important mines of gold, silver, copper and lead and in early days the placer gold mines of the Columbia, Fraser and Cariboo attracted miners from everywhere, but these have declined, and lode mines supply most of the gold as well as the other metals. The Atlin and White Horse regions in northern British Columbia and southern Yukon have attracted much attention, and the Klondike placers still farther north have furnished many millions of dollars' worth of gold, but are now al most worked out.

Climate.

In a country like Canada ranging from latitude 42° to the Arctic regions and touching three oceans, there must be great variations of climate. If placed upon Europe it would extend from Rome to the North Cape, but latitude is of course only one of the factors influencing climate, the arrangement of the ocean currents and of the areas of high and low pressure making a very wide difference between the climates of the two sides of the Atlan tic. The Pacific coast of Canada, rather than the Atlantic coast, should be compared with western Europe, the south-west corner of British Columbia, in latitude 48° to 50°, having a climate very similar to the southern coast of England.In Canada the isotherms by no means follow parallels of lat itude, especially in summer when in the western half of the coun try they run nearly north-west and south-east, so that the average temperature of 55° is found about on the Arctic circle in the Mac kenzie river valley, in latitude 5o° near the Lake-of-the-Woods, in latitude 55° at the northern end of James Bay, and in latitude 49° on Anticosti in the Gulf of St. Lawrence. It is impossible to de scribe even the climate of a single province, like Ontario or British Columbia, as a unit, as it varies so greatly in different parts. De tails should therefore be sought in articles on the separate prov inces. South of the Gulf of St. Lawrence the maritime provinces average 40° for the year and over 6o° for the summer months. The amount of rain is naturally high so near the sea, 4o to 56 in., but the snowfall is not usually excessive. In Quebec and northern On tario the rainfall is diminished, ranging from 20 to 4o in., while the snows of winter are deep and generally cover the ground from the beginning of December to the end of March. The winters are bril liant but cold, and the summers average from 6o° to 65°, with clear skies and a bracing atmosphere which makes these regions favourite summer resorts for the people of the cities to the south. The winter storms often sweep a little to the north of southern On tario, so that what falls as snow in the north is rain in the south, giving a much more variable winter, often with little snow. The summers are warm, with an average temperature of 65° and an occasional rise to 90°.

As one goes westward the precipitation diminishes, most of it, however, coming opportunely from May to August, the months when the growing grain most requires moisture. There is a much lighter snowfall than in northern Ontario and Quebec, with some what lower winter temperatures. The precipitation in southern Saskatchewan and Alberta is much more variable than farther east and north, so that in some seasons crops have been a failure through drought, but large areas are now being brought under irri gation to avoid such losses. The prairie provinces have a distinctly continental climate with comparatively short, warm summers and long, cold winters, but with much sunshine in both seasons. In southern Alberta the winter cold is often interrupted by chinooks, westerly winds which have lost their moisture by crossing the mountains and become warmed by plunging down to the plains, where they blow strongly, licking up the snow and raising the tem perature, sometimes in a few hours from to 40°. In this region cattle and horses can generally winter on the grass of the ranges without being fed. With sunshine for twenty hours out of twenty four in June, growth is almost the same in the north as for hun dreds of miles to the south, so that wheat and vegetables ripen in the Peace river valley in latitude 56°.

The climate of the Cordilleran region presents even more va riety than that of the other provinces because of the ranges of mountains which run parallel to the Pacific. Along the coast itself the climate is insular, with little frost in winter and mild heat in summer, and with a very heavy rainfall amounting to r oo in. on the south-west side of Vancouver Island and near Prince Rupert. Beyond the Coast Range the precipitation and general climate are comparatively mild and with moderate snowfall towards the south, but with keen winters farther north. The interior plateau may be described as arid, so that irrigation is required if crops are to be raised.

The Selkirk Mountains have a heavy rainfall and a tremendous snowfall on their western flanks, but very much less precipitation on their eastern side. The Rocky Mountains have the same rela tionships but the whole precipitation is much less than in the Sel kirks. The temperature depends largely, of course, on altitude, so that one may quickly pass from perpetual snow above 8,000 f t. in the mountains to the mild, moist climate of Vancouver or Victoria. North-west and north-east of Hudson Bay the climate becomes too severe for the growth of trees, and there may be perpetual ice beneath the coating of moss which serves as a non-conducting covering for the "tundras." Leaving out the maritime provinces, southern Ontario, southern Alberta and the Pacific coast region on the one hand, and the Arctic north on the other, Canada has snowy and severe winters, a very short spring with a sudden rise of temperature, short, warm summers and a delightful autumn with its "Indian summer." There is much sunshine, and the atmosphere is bracing and exhilarating. (A. P. Co.) Flora.—The general flora of the Maritime Provinces, Quebec and Eastern Ontario is much the same, except that in Nova Scotia a number of species are found common also to Newfoundland that are not apparent inland. In New Brunswick the western flora begins to appear as well as immigrants from the south, while in the next eastern province, Quebec, the flora varies considerably. In the lower St. Lawrence country and about the Gulf many Arc tic and sub-Arctic species are found. From the city of Quebec westwards there is a constantly increasing ratio of southern forms, and when Montreal is reached the representative Ontario flora be gins. In Ontario the flora of the northern part is much the same as that of the Gulf of St. Lawrence, but from Montreal along the Ottawa and St. Lawrence valleys the flora takes a more southern aspect, and trees, shrubs and herbaceous plants not found in the eastern parts of the Dominion become common.

In the forest regions north of the lakes the vegetation on the shores of Lake Erie requires a high winter temperature, while the east and north shores of Lake Superior have a boreal vegetation that shows the summer temperature of this enormous water stretch to be quite low. Beyond the forest country of Ontario come the prairies of Manitoba and the North-West Territories. In the ravines the eastern flora continues for some distance, and then disappearing gives place to that of the prairie, which is found everywhere between the Red river and the Rocky Mountains ex cept in wooded and damp localities. Northwards, the flora of the forest and that of the prairies intermingle. On the prairies and the foot-hills of the Rocky Mountains a great variety of grasses is found. Besides the grasses there are many leguminous plants valuable for pasture.

About the saline lakes and marshes of the prairie country are found Ruppia maritima, Heliotropium curassavicum, natives of the Atlantic coast, and numerous species of Chenopodium, Atri plex and allied genera. The flora of the forest belt of the North West Territories differs little from that of northern Ontario. At the beginning of the elevation of the Rocky Mountains there is a lux urious growth of herbaceous plants, including a number of rare umbellifers. At the higher levels the vegetation becomes more Arctic. Northwards the valleys of the Peace and other rivers differ little from those of Quebec and the northern prairies. On the western slope of the mountains, that is, the Selkirk and Coast ranges as distinguished from the eastern or Rocky mountain range, the flora differs, the climate being damp instead of dry. In some of the valleys having an outlet to the south the flora is partly peculiar to the American desert, and such species as Purshia tridentata and Artemisia tridentata, and endemic species of Gilia, Aster and Erigonum are found. Above Yale, in the drier part of the Fraser valley, the absence of rain results in the same character of flora, while in the rainy districts of the lower Fraser the vegetation is so luxuriant that it resembles that of the tropics. So in various parts of the mountainous country of British Colum bia, the flora varies according to climatic conditions. Nearer the Pacific coast the woods and open spaces are filled with flowers and shrubs. Liliaceous flowers are abundant, including various species of Erythronium, Trillium, Allium, Brodeaea, Fritillaria, Lilium and Camassia. (X.) Fauna.—The larger animals of Canada are the musk-ox and the caribou of the barren lands, both having their habitat in the far north ; the caribou of the woods, found in all the provinces except Prince Edward Island; the moose, with an equally wide range in the wooded country; the Virginia deer, in one or other of its varietal forms, common to all the southern parts; the black-tailed or mule deer and allied forms, on the western edge of the plains and in British Columbia; the pronghorn antelope on the plains, and a small remnant of the once plentiful bison in northern Alberta and Mackenzie. The wapiti or American elk at one time abounded from Quebec to the Pacific, ranging as far north as the Peace river, but is now found only in small numbers from Manitoba westward.

In the mountains of the west are the grizzly bear and the black bear. The black bear is also common to most other parts of Canada ; the polar bear everywhere along the Arctic littoral. The large or timber wolf is found in the wooded districts of all the provinces, and on the plains there is also a smaller wolf called the coyote. In British Columbia the puma or cougar still fre quently occurs ; and generally distributed in wooded areas are the common fox and its variety, the silver fox, the lynx, beaver, otter, marten, fisher, mink, skunk and other fur-bearing animals. The wolverene is largely confined to the barren lands, which are also inhabited by the arctic fox. Mountain and plain and Arctic hares and rabbits are plentiful or scarce in localities, according to seasons or other circumstances. In the mountains of British Columbia are the bighorn or Rocky Mountain sheep and the Rocky Mountain goat, while sheep of two or three other species are also found from nearly pure white in the north to black in certain areas in the southern Canadian Rockies.

The birds of Canada are mostly migratory, and are those common to the northern and central states of the United States. The wildfowl are, particularly in the west, in great numbers; their breeding grounds extending from Manitoba and the western prairies up to Hudson Bay and the barren lands and Arctic coasts. The several kinds of geese—including the Canada goose, the Arctic goose or wavey, the laughing goose, the brant and others all breed in the northern regions, but are found in great numbers throughout the several provinces, passing north in the spring and south in the autumn. There are several species of grouse, in cluding the ruffed grouse, ptarmigan and sharp-tailed grouse of the plains. In certain parts of Ontario the wild turkey formerly occurred, and the so-called "quail" or "bob-white" still inhabits the southern part of the province.

The golden eagle, bald eagle, osprey, and a large variety of hawks are common in Canada, as are the snowy owl, the horned owl and other owls. The raven is found only in the less populated districts, but the crow is common everywhere. Song-birds are plentiful, especially in the wooded regions, and include the Ameri can robin, oriole, thrushes, the catbird and various sparrows; while the introduced English sparrow has multiplied excessively and become a nuisance in the towns. More recently introduced but spreading rapidly are the European starling in the east and the Japanese starling in British Columbia. The smallest of the birds, the ruby-throated hummingbird, is found everywhere, even up to timber line in the mountains. The seabirds include a variety of gulls, terns, guillemots, cormorants and ducks, and in the Gulf of St. Lawrence the gannet is very abundant. Nearly all the sea-birds of Great Britain are found in Canadian waters or are represented by closely allied species.

The Migratory Birds Convention Act of 1923 involved an agree ment between the United States and Canada for the protection of bird life.

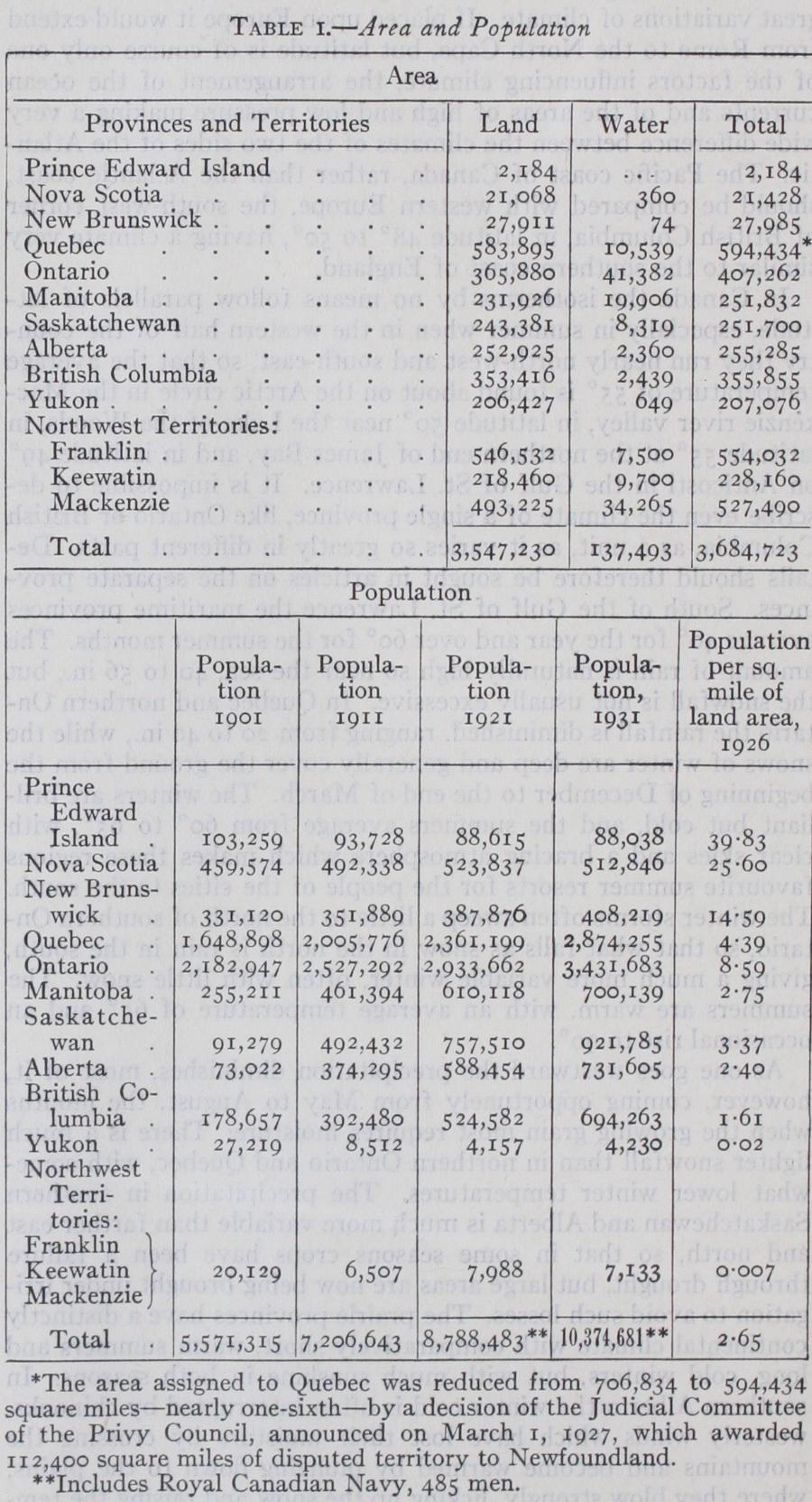

The land and water area of Canada was given by official figures for 1927 as 3,684,723 square miles, being about 3% larger than that of the Continental United States with Alaska (3,564,658 square miles) and about 2% smaller than that of the continent of Europe (3,776,700 square miles).

Population. The decennial census of Canada of June 1, 1921, showed a total population of 8,787,949- This figure was increased by the census of 1931 to a gain of 1,586,247 for the decade. The increase in percentage for that decade was 18.o5. Table 1 below shows the land and water areas of the various provinces and territories as of 1927, and the population as enumerated in the censuses of 1901, 1911. 1921, and 1931.

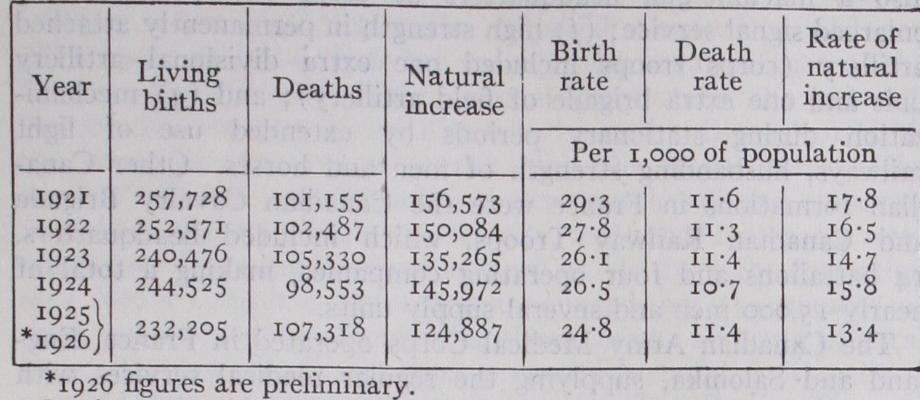

With regard to natural increase, only approximate figures were available prior to 1921. For the intercensal period 1901-1911 the surplus of births over deaths was estimated at 853,566 and for 1911-1921 at 1,150,659. The figures for the nine provinces for calendar years beginning with 1921 were as During 1926 the birth rates ranged from 32-1 per thousand in Que bec to 17.4 in British Columbia, while the rate of natural increase ranged from 17.6 per thousand in Quebec and Saskatchewan down to 7.8 per thousand in British Columbia. About one-third of the present natural increase is due to Quebec.

Races.

At the census of 1921 it was found that 83.31% of the population were of British or French origin. The French population, estimated at 8o,000 in 1763, had increased in 1921 to 2,452,751 and now constitutes 27.91% of the population. of the population are of British origin. British settle ment did not begin on a large scale until the Loyalist movement which followed the American revolution. Another period of active immigration occurred during the middle third of the 19th century, but the greatest influx from all countries took place during the decade preceding the war 1914-18. From 1906 to 1915 inclusive, more than two and a half million immigrants entered the country.

Migration.

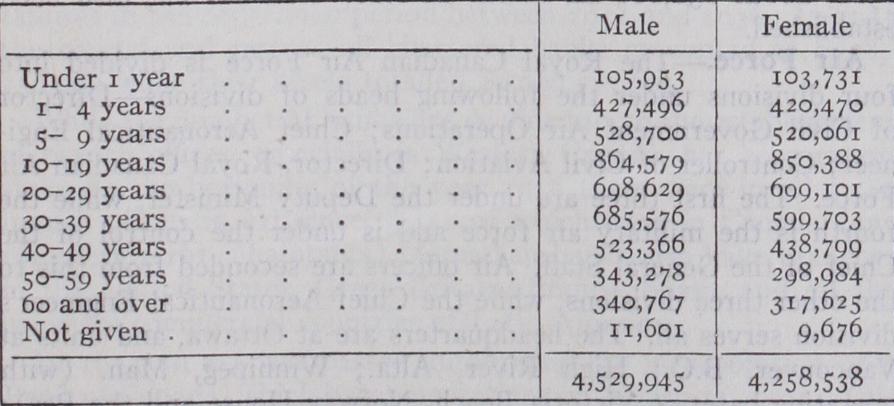

The movement reached its climax in 1913, when 402,432 immigrants were enumerated. During the war period, the stream of British immigration was practically cut off, and a large proportion of the non-British immigrants who had come in during the pre-war boom returned to their native countries or emigrated to the United States. Hence, of the total population in 1921, 77.75% were Canadian-born, 12.12% were born in other parts of the British Empire, and only 10.13% (89o,82), were born in other countries including the United States. Of the 890,282 foreign born, 514,182, or 57-75% were naturalized, leav ing only 376,100 alien residents. Of the population aged Hp years or over, in the nine provinces, 62.12% gave English, and gave French, as their native tongue, while 84.79% could speak English. Within the same age limits, 94.26% could read and write and 5.1o% could not do either.Largely as a result of immigration, the population is strongly masculine, the proportions being 515 males to 485 females. The same cause has affected the age distribution, so that an exception ally large proportion of the population is concentrated in the most productive years of life. The median age, which was 18.8o years in 1871, had increased to 23-94 years in 1921. The follow ing table shows the distribution by age and sex in 1921: Religious Denominations.—Of the total population of 1921, 97.5% were classified as belonging to some Christian denomina tion or sect, 1.9% as non-Christian (including Jews and adherents 'Quebec statistics are from provincial sources until 1926, when Quebec became a part of the Registration Area.

of Eastern religions) . The principal denominations were Roman Catholics 38.57%; Presbyterians, 16.o4%; Anglicans, 16.o2%; Methodists, 13.19%; Baptists, 4.80%; Lutherans, 3.26%; Greek Church, 1.93%; Jews, 1.42%; Mennonites, .67%; all others, 4.10%. Since the date of the 1921 census, there has been organ ized the United Church of Canada, which includes the groups formerly classed as Presbyterians, Methodists and Congregation alists, and now constitutes the largest single Protestant body. A large number of the Presbyterians did not enter this union, and this group continues as a separate denomination.

Rural and Urban Population.

The Canadian census of 1931 classes of the population as urban and 46.29% as rural. The degree of urbanization in Canada was in 1921 less than in the United States: thus, 36.55% of the population of Canada lived in places of 5,00o or over as compared with 47% in the United States. Of the total increase in population which occurred between 1921 and 1931, urban communities absorbed 1,219,936, rural 366,311. The largest cities were in 1931 Montreal Toronto (631,207), Winnipeg (218,785), Vancouver Hamilton (145,547), Quebec Ottawa (126,872), Cal gary (83,761), Edmonton (79,197), London (71,148), Halifax St. John (47514), and Victoria (39,082).

Government.

Canada is one of the five self-governing Do minions of the British Empire. Though still retaining some ves tiges of her former colonial status—such as the appointment of the governor-general by the British government, the privileges of appeal to the judicial committee of the Privy Council, and the necessity of applying to the British parliament for the amendment of the British North America Act, which is the fundamental law of the Canadian constitution—Canada has been declared by the Imperial Conference of 1926 to be "equal in status" with the mother country. The many unwritten conventions of the British constitution hold good in Canada; but there is an important differ ence between the British and Canadian constitutions, in that the Canadian is federal.The British North America Act, which embodies the terms of the federal agreement of 1867, lays down, in sections 91-93, the subjects of legislation which are assigned respectively to the Do minion and the provinces. The former has exclusive legislative authority in all matters relating to the regulation of trade and commerce, military and naval defence, navigation and shipping, banking and currency, marriage and divorce, etc. ; the latter in all matters relating to education, municipal government, property and civil rights within the province, licenses, etc.

Executive Power.

In the Dominion, executive power rests in the hands of the governor-general, who represents the king of Great Britain, and is appointed by the British Government. The governor-general is, however, advised by the prime minister and his colleagues in the cabinet, who at the same time are members of the King's Privy Council for Canada and sit in the Dominion parliament.

Legislative Power.

The Dominion legislature is bicameral: it is composed, in addition to the representative of the Crown, of a Senate numbering 96 members, who are appointed for life by the governor-general in council; and a House of Commons, num bering 245 members in 1927, who are elected by the people for the duration of parliament, which may not be longer than five years. In the provinces, the Crown is represented by a lieutenant governor, appointed by the Dominion government. He is advised by an executive council, composed of a prime minister and a varying number of ministers, all of whom sit in the legislature. In seven out of the nine provinces, the legislature is unicameral, being composed of a Legislative Assembly, elected by the people for a term of four years. Only in Quebec and in Nova Scotia is there a second chamber, styled in both provinces a Legislative Council, and composed of nominees of the provincial govern ment.

Justice.

The administration of justice is largely in the hands of the provinces, though the judges in the higher courts are ap pointed by the Dominion government, and the Dominion has had since 1875 a Supreme Court. Both from the provincial courts and from the Supreme Court there may be, in certain cases, an appeal " to the judicial committee of the Privy Council. (W. S. WA.) Historical.—In the earliest European settlements in Canada, the necessity of protection against Indians caused the formation of a militia, and in 1665 companies were raised in every parish. The military history of the Canadian forces under French rule is full of incident, and they served not only against Indian raiders but also against the troops of Great Britain and of her North American colonies. Six militia battalions took part in the defence of Quebec in 1759, and even the transfer of Canada from the French to the British crown did not cause the disbandment of the existing forces. The French Canadians distinguished themselves in the War of American Independence, and in particular in the defence of Quebec against Montgomery and Arnold. In 1787 an ordinance was made whereby three battalions of the militia were permanently embodied, each contingent serving for two years, at the end of which time a fresh contingent relieved it. The brunt of the fighting on the American frontier in the War of 1812 was borne by the permanent force of three battalions and the fresh units called out. all these being militia corps. The militia was again employed on active service during the disturbances of 1837, and the "Active Militia" in 1863 had grown to a strength of 25,000 men. The Fenian troubles of 1864 and 1866 caused the embodiment of the Canadian forces once more. In 1867 took place the unification of Canada, after which the whole force was completely organized on the basis of a militia act (i868). A department of Militia and Defence with a responsible minister was established. and the strength of the active militia of all arms was fixed at 40.000 rank and file. Two years later the militia furnished 6.eoo men to deal with the Fenian Raid of 1870, and took part in Colonel (Lord) Wolseley's Red River expedition. In 1871 a tiny permanent force, serving the double purpose of a regular nucleus and an instructional cadre, was organized, and in 1876 the Royal Military College of Canada was founded at Kingston. In 1885 the Riel rebellion was dealt with, and the important action of Batoche won, by the militia, without assistance from regular troops. In the same year Canada contributed a force of oyageurs to the Nile expedition of Lord Wolseley ; the experience of these men was of great assistance in navigating the Rapids. The militia sent contingents of all arms to serve in the South African War, 1899-1902, including "Strathcona's Horse," a spe cial corps. recruited almost entirely from the Active Militia and the North-west Mounted Police. The latter, a permanent con stabulary of mounted riflemen, was formed in 1873.After the South African War an extensive scheme of reorgan ization was taken in hand. the command being exercised for two years (1902-1904) by Major-General Lord Dundonald, and sub sequently by a militia council (Militia Act 1904), similar in con stitution to the home Army Council.

After 1910 Canadian military organization changed very much. Its two most important features were the final war organization, and the peace organization which succeeded it. The principal mili tary effort of Canada from 1914 to 1918 consisted in the organi zation and maintenance of the Canadian Corps, consisting of the 1st. 2nd, 3rd. and 4th Canadian divisions and corps troops. This force, while technically an army corps of the British Army, differed from other army corps in that it was an integral tactical unit. moving and fighting as a whole.

War-time Organization.

Its high tactical value resulted mainly from (a) great mobility, aided by two additional mechan ical transport companies (for machine-gun battalions and engi neer brigades); (b) high and consistent infantry strength, due to each division having three brigades of four battalions of "roc) men each. one engineer brigade of three battalions in each divi sion (eliminating the necessity of supplying working parties from infantry) and to the possession of its own system for handling reinforcements; (c) staffs almost double strength and staff officers constantly interchanged; (d) an unique machine-gun organiza tion, comprising two motor machine-gun brigades with the corps and one machine-gun battalion of 96 guns with each division, also a machine-gun headquarters at corps headquarters; (e) enlarged signal service; (f) high strength in permanently attached artillery (corps troops included one extra divisional artillery unit and one extra brigade of field artillery) ; and (g) mechani zation during stationary periods by extended use of light railways, husbanding strength of men and horses. Other Cana dian formations in France were the Canadian Cavalry Brigade and Canadian Railway Troops, which included headquarters, 14 battalions and four operating companies, making a total of nearly 15.000 men and several supply units.The Canadian Army Medical Corps operated in France, Eng land and Salonika, supplying the regular medical services with the corps and other troops and also 14 general and seven sta tionary hospitals, four small forestry corps hospitals, 12 conva lescent hospitals and one mobile laboratory. The Canadian Forestry Corps operated in England and France with 24.000 all ranks. The Canadian Army Dental Corps had a strength of 9o3 all ranks. Special formations were the Accountant General's Branch, the Canadian Army Pay Corps and the Department of the General Auditor. Canadian troops in France and England were administered by the Minister of Overseas Military Forces of Canada with a headquarters in London.

Post-War Organization.

During the session of 1922 a Na tional Defence Act was passed, consolidating the Naval Service, the Air Board and the Dept. of Militia and Defence into the Dept. of National Defence. The Act became effective by procla mation on Jan. r, 1923. Under it there is a Minister of National Defence and a deputy-minister; a Defence Council was consti tuted to advise the minister. The senior non-civil officer is the chief of the general staff.

Military Forces.

The small permanent military force is used for the maintenance of organization and the instruction of the non-permanent troops, who constitute the first line fighting force. For purposes of training, discipline, mobilisation. etc.. the coun try is divided into 11 districts, each district under permanent commanders with small staffs. Infantry is organized in brigades for training and administration, but based, for recruiting and reinforcement, on a regimental system with active and reserve battalions (122 in all), perpetuating by their names the pre-War militia regiments and units of the Canadian Corps. The organ ization of other arms is such as to provide for the formation of complete divisions with the necessary depots for reinforcements. The units of the permanent force and a large proportion of the non-permanent units, are allied with regiments and other units of the British army. The strength of the permanent militia was limited by the Militia Act Amending Act of 1919, to ro.000. but the authorized establishment up to 192S was only 3.600. Royal schools of instruction are conducted at all stations of the per manent force; the Canadian Small Arms School is the only school, however, which is an independent unit of the permanent force. The total establishment of the Canadian forces is, in 1928, about 130,000 all ranks. A reserve militia has also been established.

Air Force.

The Royal Canadian Air Force is divided into four divisions under the following heads of divisions—Director of Civil Government Air Operations; Chief Aeronautical Engi neer; Controller of Civil Aviation; Director, Royal Canadian Air Force. The first three are under the Deputy Minister, while the fourth is the military air force and is under the control of the Chief of the General Staff. Air officers are seconded from this to the other three divisions, while the Chief Aeronautical Engineer's division serves all. The headquarters are at Ottawa, and units at Vancouver, B.C. ; High River, Alta. ; Winnipeg, Man. (with operating bases at Victoria Beach, Norway House and the Pas) ; Camp Borden (the main training base) ; Ottawa, Ont. ; and Dart mouth. N.S. The strength of the force in 1928 was 76 officers and 450 men permanently employed, of which 63 officers and 222 men are employed on Civil Government Air operations. A reserve is in process of formation. Its functions were air force training and operations, the control of commercial flying and the conduct of flying operations for civil branches of the government service. In 1925 and 1926 the force was in process of reorganization.(X.) Navy.—Not until of ter the Imperial Conference of 1909 did Canada decide to bear her share in the naval defence of the Empire. In 1910, a Navy Department was formed, charged with the organization of a Naval Force, to be at the disposal of H.M. the King for the general service with the Royal Navy. The cruisers "Niobe" and "Rainbow" were purchased and stationed at Halifax and Esquimalt respectively, and these two bases were taken over from the Imperial authorities. In 1911 the formation of a Royal Canadian Navy was announced, but the number of ships and the method of providing them became an acute political issue. The Laurier Government proposed to build, in Canada if possible, four cruisers and six destroyers. The Borden Govern ment plan was to lay down three battleships for the Royal Navy, which should be at the call of the Royal Canadian Navy, when that force came into existence. Neither plan materialized before the outbreak of the war in 1914. During the war the two old cruisers, assisted by a destroyer and two submarines were em ployed in patrolling, and, on both Atlantic and Pacific Coasts, large flotillas, manned chiefly by volunteers, came into being and did all patrol, minesweeping and convoy protection work in Canadian waters.

After the visit of Lord Jellicoe to Canada in 1919 the Canadian Government decided to maintain the Navy at pre-war level and the Imperial Government presented to Canada a light cruiser and two destroyers to replace the obsolete ships. The war time personnel was demobilized and re-organized and in 1922 the Navy Department was amalgamated with the Department of National Defence. In 1936 the authorized permanent personnel of the Royal Canadian Navy was 117 officers and 862 men, the latter serving as a rule under seven year engagements ; the establish ment of the Naval Reserve, recruited from among the seagoing population, was 7o officers and 43o men enrolled for five years; and the Naval Volunteer Reserve numbered Io officers and 93o men under a three year enrolment. Four destroyers and one mine sweeper were maintained in commission ; and there were training posts, dockyards, and shops at Halifax and Esquimalt.

(S. T. H. W.) Banking and Finance.—The Act of Confederation 1867 brought about the unified control of the banking system of the country, and by the Bank Act of 1871 a decennial revision of banking law was provided for. This system has worked smoothly, and changes have been in the way of natural development. The currency of the country is provided for by a restricted note issue of chartered banks secured by a system of mutual liability under which the assets of all the banks are liable for the notes of each one. In 1871 there were twenty-three chartered banks, with a paid-up capital of $40,000,000 and total assets of $136, 000,000. The maximum number of banks was forty-one in 1886. By 1931 this number had fallen to ten. Amalgamations and a few failures account for the reduction, but the direct loss to the public as a result of bank failures has been slight. There were no failures in the depression period between 1931 and 1936. In the capital and rest of all chartered banks amounted to $278, 250,000 while their assets totalled While the number of banks has declined to io the establishment of branch offices, especially in Western Canada, has been exten sive. At the beginning of the year 1936 there were in all 3,580 branch offices in existence, 3,431 of which were in Canada (one for every 3,19I inhabitants) . Canadian banks also have branches in the United States, Great Britain, France, Spain, and all the principal commercial countries of Latin America.

In 1934 an act was passed authorizing the incorporation of a Bank of Canada, which began operations on March II, 1935. This new agency, analogous in many of its functions to the Regional Banks of the U. S. Federal Reserve system, is required to main tain a gold reserve equal at least to 25% of its total note and deposit liabilities in Canada. Chartered banks, hitherto unre stricted as to their reserves against deposits, are now obliged to keep a reserve of at least 5% of their deposit liabilities within the Dominion in the form of deposits with and notes of the Bank.

The net debt of the Dominion in 1871 was about $78,000,000; in 1911 it was $340,042,052 and in 1924, The figure was reduced to $2,177,763,959 by but mounted again during the period of depression to $2,846,110,758 in 1935. In terest on the public debt in 1911 was in 1935 it was $138,533,202. War pensions, the growth of population, increas ing government activities, railway deficits and rising prices, all added to public expenditure, quite apart from the vast sums raised during the war (1914-18) for the maintenance of the army. The expenditure in 1911 on account of the consolidated fund was about $88,000,000. In 1935 it was $354,368,220. To this latter sum must be added the capital expenditures, railway deficits, and relief costs which brought the total expenditures to $478,004,747. The national wealth of Canada in 1933 was estimated at $25,768, 236,000 with the provincial distribution as follows : Ontario, $8,795,801,000; Quebec, $6,738,181,000; Saskatchewan, $2,527, 147,000; Alberta, $2,035,576,000; British Columbia, $2,430, 890,000; Manitoba, $I,562,42I,000; Nova Scotia, $790,290,000; New Brunswick, $130,297,000; Prince Edward Island, $138, 699,000; Yukon, $18,934,000. The wealth per capita averaged $2,413, being highest in Yukon, British Columbia, and Alberta. The national income in 1928 was estimated at $6,342,000,000; in 1933 it was estimated at $3,340,000,000. The amount of income assessed for income taxes in the former year was $1,040. 232,948; in the latter it was $944,091,564; and by 1935 it had fallen to The financial problem of the country was made more difficult by the burden of the vast railway system which had to be taken over by the Government soon after the War.

Customs duties were the largest source of revenue in 1935, fur nishing $76,561.975 of the $358,474,760 receipts of the con solidated fund. Excise duties were $43,189,655; income taxes amounted to $66,8o8,o66; sales taxes totalled $72,447,311; and taxes on cheques, transportation, etc. were $39,744,759• The combined yield of the last two items had trebled since 1931.

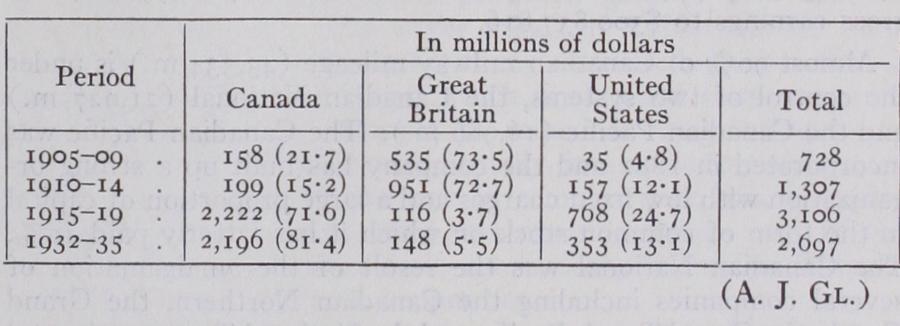

Canada was still a considerable borrower abroad in 1935, and it is important to note that after 1914 the greater part of these borrowings were from the United States, instead of Great Britain which had supplied nearly all the foreign capital borrowed by Canada before 1914.

The following table shows the nature of the change in respect to the sale of Canadian securities:— Communications and Transport.—Rapid increase in trans port facilities has been accompanied by improved communications. In 1934 telegraph wire mileage totalled 366,706 of which the Canadian National Telegraph owned 164,831 and the Canadian Pacific 177,800. Canada has six transoceanic cables, five on the Atlantic and one on the Pacific. The telegraph has been rapidly extended with wireless and radio stations. In 1935 there was a total of 815,124 stations. In 1934, 1,193,7 29 telephones were in use, or II.o per Ioo of population with 5,133,521 m. of wire. The number of post offices in operation declined from 12,409 in 1930 to 12,035 in 1934 but increased again to 12,069 in Postal revenues for 1935 were $36,185,222. In 1934 there were 4,343 rural mail routes with 238,764 boxes.

Canada is primarily a new country with a small population ex porting such bulky raw materials as wheat, lumber, pulp and paper, and minerals to densely populated industrial countries. Cheap water transportation is fundamental. Canadian ports are seriously affected by climatic considerations. Montreal is closed in the winter season and Halifax and St. John are too far distant from the interior to compete with United States Atlantic ports. Vancouver has benefited as an export centre for wheat by the opening of the Panama Canal. The export of wheat from the Prairie provinces intensifies the transport problem since it pro duces a peak load for Great Lakes shipping. The handling of great quantities of wheat during the rush season involves the use of specially constructed boats, "lakers," and of elaborate loading and unloading facilities at Port Arthur and Fort William, Port Col borne, Buffalo and the Georgian Bay ports. The Canadian Canal at Sault Ste. Marie has a depth of 19 feet and the American Canal 25 ft. The Welland Canal has been deepened to a minimum of 25 ft. so that lake boats of 22 ft. draught can proceed to the foot of Lake Ontario; and it is hoped that the St. Lawrence will be deepened to 3o ft. to permit ocean-going vessels to reach the lakes. Since confederation in 1867 Canada has expended $318, 332,293 chiefly on canals facilitating Great Lakes traffic. Toll charges on canals were abandoned in 1903.

Railway facilities have also been improved in relation to the ex port of wheat from the prairie provinces. Especially since 1900 railways have been rapidly extended for the development of traffic in western Canada, and the marked increase in the export of wheat has led to the construction of new lines from Winnipeg to Fort William and Port Arthur and from Georgian Bay ports to Mon treal as well as to the construction of a line from Winnipeg to Cochrane and Quebec. An additional outlet for trade of the Prairie provinces resulted from the completion in 1931 of a rail way to Churchill on Hudson bay. The development of the mineral industry and of pulp and paper mills in the Precambrian territory of Canada has been followed by the construction of numerous lines in northern Ontario and in northern Quebec, including the Temis kaming and Northern Ontario Railway and the lines to the Saguenay country, and in northern Manitoba. As in the case of canals, railway construction has involved heavy expenditures on the part of the federal and of the provincial governments. Land grants up to 1935 of the federal government total 31,881,642 ac., and of provincial governments ac., cash subsidies of the federal government $177,989,88o, of provincial governments and of municipalities $13,268,691, railway bonds guaranteed by the federal government and by pro vincial governments $93,261,489. Capital expenditures on govern ment railways to March 31, 1935 totalled $440,796,896; and provision is regularly made for deficits on these lines.

In 1934 the total capitalization of all Canadian railways was $4,606,323,231; operating expenses amounted to $251,991,667 and gross earnings to $300,837,816.

Almost 90% of Canadian railway mileage (43,334 m.) is under the control of two systems, the Canadian National (21,927 m.) and the Canadian Pacific (16,986 m.) . The Canadian Pacific was incorporated in 1881 and the company has built up a strong or ganization with low fixed charges and a large proportion of capital in the form of common stock on which it has latterly paid io%. The Canadian National was the result of the amalgamation of several companies including the Canadian Northern, the Grand Trunk, the Grand Trunk Pacific and the National Transcontinental which found themselves in difficulties through dependence on gov ernment guaranteed bonds and the high costs of operation during the war. The post-war period has been characterized by a joining up of the various units and a rounding out of the organization as a system. Both lines have connections with American roads and in 1934 the single-track mileage of Canadian railways within the borders of the United States was 339.

The financial position of these two important systems is closely dependent on railway rates. Rates are under the jurisdiction of the board of railway commissioners formed in 1903. It also regulates telephone, telegraph and express rates, and deals with problems of location, construction, and operation of the railways. The procedure of this Board is informal; 94.7% of the applications to it in 1934 were disposed of without formal hearings. To cope with some of the problems. which grew out of the depression, a special tribunal, with higher authority though narrower jurisdic tion than that of the Board, was created under the terms of the Canadian National-Canadian Pacific Act of 1933 to settle disputes between the two railway systems.

The transcontinental main lines with termini at the Canadian ports are supplied with traffic by numerous branch lines or feeders. In new territory further extension has been made with river steamboats, as on the Mackenzie and the Yukon and with the organization of air transport systems as in newly opened mining districts. Aircraft are used in new districts for passenger and mail service and in government work of surveying, mapping and preven tion of forest fires. In 1935, there were 38o licensed aircraft carrying a total personnel of 330,683 ; lb. of freight or express and 1,126,084 lb. of mail. The two railway companies have their own organization for handling express traffic.

Transport facilities have been improved with the introduction of the automobile and the construction of roads. In 1935 Canada had 409,269 miles of road, of which 315,627 miles were earth, miles gravel, 1,655 waterbound macadam, 3,214 bituminous macadam, 1,821 bituminous concrete, 1,906 cement concrete. Capital expenditures of the Dominion on roads in 1934 was while those of the provincial governments amounted to $29,952,814 and those of the municipalities to Motor vehicles had increased from 2,130 in 1907 to 1,129,532 in Each province has its own system of regulations, and in $50,622,683 were collected in taxes on motor vehicles. For short haul traffic in densely populated sections of Canada the motor vehicle has become a competitor of the railroads, but it has also been important in providing supplementary traffic for long distance railroad hauls.

Electric railways have decreased in mileage since 1925 as a result of the development of transportation by motor cars. In electric railway mileage totalled 1,293 m. and car mileage 120,035,625; passengers, 595,143,903; freight, 1,939,833 tons.

Improvement of inland transportation facilities has been re sponsible for a rapid growth of ocean shipping. In 1935 the total tonnage (of sea-going vessels) entered and cleared at Cana dian ports was 57,059,848. Of the total registered tonnage of vessels entered, 11,883,371 were British, 5,667,708 Canadian, and 10,961,178 foreign. Several steamship lines run between Canada and Great Britain and Europe on the Atlantic, and Canada and Asia and Australia on the Pacific. The Canadian Pacific operates an important subsidiary ocean steamship company and the Ca nadian National has a valuable ally in the Canadian Government Merchant Marine, which came into existence during the later years of the war. In 1925 this company had 49 vessels of a deadweight tonnage of 324,986 which made 235 voyages. On Dec. 31, 1934, however, its fleet had diminished to 1 o vessels with a deadweight of only 88,579 tons. (H. A. I.) Agriculture.—The possible farm land in the dominion of Canada is estimated at 361 million acres, which is one-sixth of the total land area ; 45.1% was occupied in 1931, as compared with 17.7% in 1901. Saskatchewan and Alberta increased their farm acreage from 62 to 95 million acres in this period. Most of the free land, suited to ordinary agriculture and within prac ticable distance of a railroad, has been alienated : and since 1918 the West has been engaged in settling more intensively land that has already been picked over. New settlement now usually in volves the purchase of land : and estimates indicate that in 1922 there were in the prairie provinces some 20 million acres of land within 20 miles of a railway in private hands, but uncultivated. Only the southern part of the prairies is flat and treeless : and here only is lack of rainfall an urgent probjem. The northern part is rolling park country, and the cultivable area runs north west into the still undeveloped region of the Peace river and northern British Columbia. Canada, both east and west, is in the main a country of family farms and occupying ownership. In 1931 farms of 101-20o acres formed over 30% of all farms. In British Columbia, which is distinguished by the intensive culti vation of fruit and dairy products, farms of II–so acres pre dominate : in the older settled provinces of the East, dairying leads, followed by fruits and potatoes, and here the farm of 51 100 acres predominates. The larger farms, 201 acres and up, predominate in the prairies ; and the expansion of the prairie provinces, 1901-31, is responsible for the increase in average farm acreage for Canada as a whole. There is, however, no marked tendency to the very large farm, though the technical conditions in the prairies clearly favour large-scale operation— flat land being suited to tractor cultivation. Hitherto such farms have been beaten by the labour problem. In 1931, 80•05% of the farm area of Canada was occupied by its owners, as compared with 90.7% in 1901. Renting is still a pis-aller or a stepping-stone to ownership; and the small decrease in occupying ownership, 1901-1931, is due entirely to the prairie provinces, where some farms are rented on a share basis by tenants wio hope one day to buy.

In 1934 the gross agricultural wealth of Canada was $5,608, 157,000 distributed as follows: land, $2,226,366,000; buildings, implements and machinery, $650,664; livestock, etc., $456,856; agricultural products, $931,347,000. With the opening of the West, the relative importance of the East has decreased. In 1901 Ontario and Quebec had 75% of all farm property; in 1934 only 45%. Ontario leads in the value of build ings (36.2% of the total) and of livestock (31.2% of the total) . The agricultural production of the entire Dominion in 1934 was and of this total Ontario and Quebec produced $480,605,000; the three prairie provinces $350,314,000. The main cash product of the East is milk, and the favourite cow of Ontario is the Holstein, a heavy yielder of milk, which thrives on the rich ensilage fed to it in the stall. The West since 1918 has made rapid strides in dairying and other branches of mixed farming, but as a cash product wheat still ranks first. The average value of the wheat crop (1932 to 193 5) was $157,801,500, nearly all of it spring wheat grown in the West. Though Canada pro duces less than i o% of the world's wheat she exports from to of her crop, and this normally forms about 3o% of the wheat and wheat flour entering the circle of international trade. The leading spring wheat is Marquis, discovered by Sir Charles E. Saunders, dominion cerealist, in 1904 and introduced into Western Canada in 1907, and since 1909 the principal spring wheat of North America. Since 1925 a new wheat, Garnett, selected by Sir Charles, has been introduced. It is a cross from Marquis but matures from 6 to i o days earlier. Agricultural research in Canada is shared between the dominion, which maintains experi mental farms and field stations in every province, and the prov inces, each of which has in its provincial university an agricultural department devoted to the science and economics of agriculture. Manitoba's special enemy is wheat rust; and intensive research has been devoted to the production of a rust-resistant wheat which is not defective in other qualities. The rust spores use the barberry plant as a winter host, but since they are carried by the wind from points hundreds of miles away, the local de struction of this plant is not sufficient.

Four features of outstanding economic importance,

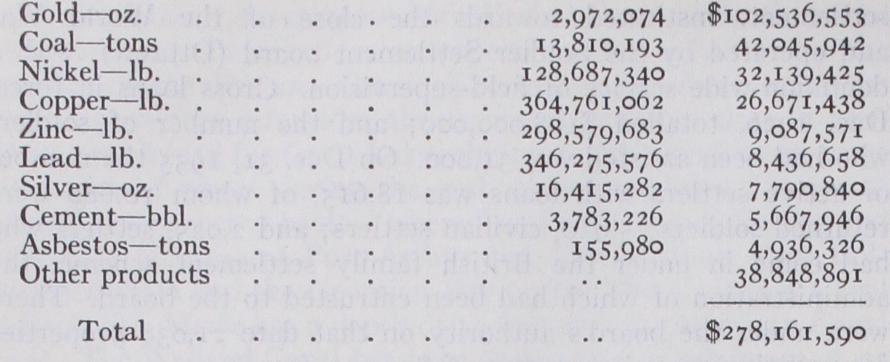

are: (I) The growth of the pool method of marketing by farmers' co-operative organizations. This development has been most suc cessful with respect to wheat, livestock, and fruit. Reports for showed 697 co-operative associations with 2,604 branches and 341,020 share holders actively engaged in business. The combined assets exceeded $105,000,000 and the value of their plant and equipment amounted to $38,850,488. Sales of farm products totalled $117,783,560 for the year while supplies han dled were valued at $7,991,755. Grain and seed co-operatives alone comprised 3o associations with 2,137 places of business and 170,081 share holders; their assets were $88,298,067 ; plant, $32,343,910; and sales of farm products, (2) The growth of grain shipment from the port of Vancouver, which has the advantage of being open the whole year round. The export of wheat from Vancouver rose from II million bushels in 1920-21 to 52 million bushels in 1925-26. The movement through Vancouver depends (a) upon the total size of the Canadian crop, and (b) the relative size of the crop of Alberta, the province nearest to Vancouver. In 1935 when the wheat production figure both for Alberta and for Canada was unusually low, exports through Vancouver amounted to 45-3 million bushels.(3) The completion and stabilization of the scheme of soldier settlement, instituted towards the close of the World War and operated by the Soldier Settlement board (Ottawa), with a dominion-wide service of field-supervision. Gross loans in force, Dec. 1926, totalled $108,0o0,000; and the number of soldiers who had been assisted was 31,00o. On Dec. 31, 1935 the number of active settlers with loans was 18,615, of whom 10,68o were returned soldiers; 5,910, civilian settlers; and 2,025, settlers who had come in under the British family settlement scheme, the administration of which had been entrusted to the board. There were under the board's authority on that date 21,038 properties representing a net investment of (4) The growth of the tobacco industry in Eastern Canada, and especially in Western Ontario, under the stimulus of the 25% British preferential rate. Total exports of tobacco, 1922-$1 millions: 1935—$2a millions. Tobacco is more profitable than corn (maize) as a cash crop, and relieves the grower from the loss incurred by the ravages of the corn borer. Over 50% of Ontario tobacco is of the Burley variety, while in Quebec a corresponding percentage is cigar tobacco. One of the exper imental divisions of the Canadian Department of Agriculture is engaged in research upon the major problems of the culture, harvesting, and curing of tobacco. (C. R. F.) Minerals and Mining.—Most of the economic minerals occur in Canada, as might be expected from its great area and varied geology, and more than 6o products were reported in by the Dominion Bureau of Statistics; but only the more important need be referred to. Coal for many years stood first in value until in 1931 it was overtaken by gold. The estimated value of its output in 1935 was $41,888,533. Nova Scotia has bituminous coal of the Carboniferous age, more than half of which lies under the sea. Coke made from it and hematite, also mined beneath the sea in Newfoundland, make the basis of the important steel industry of Sydney. Alberta produces nearly as much coal, but of Cretaceous age and largely lignitic, though the quality improves towards the mountains. British Columbia mines less than half as much as Alberta, most of it Cretaceous, but some of it making excellent coke for the smelters.