Candle

CANDLE, a rod of fatty or waxy material through the centre of which runs a fibrous wick. Modern candles are the successors of the early rush-lights which consisted of the pith of rushes soaked in household grease. An improvement was made by the introduction of flax ("inkle") and cotton threads, which were dipped in tallow heated to a temperature slightly above its melt ing-point, and allowed to cool until the coating had solidified.

Alternate dipping and cooling was continued until the desired thickness was obtained. The manufacture of such "tallow-dips"- one of the most ancient forms of illuminant—was for centuries a house industry. In Paris, in the 13th century, there was a guild of travelling candle-makers who went from house to house making candles.

Beeswax candles have been used from early times and are mentioned by the Roman writers. For mystical reasons the Catholic Church prescribes beeswax candles for Mass and other liturgical functions.

Spermaceti, a white crystalline wax obtained from the head cavity of the sperm or "right" whale, came into use in the latter half of the 18th century; the sperm candle, weighing one-sixth of a pound and burning 120 grains per hour was adopted by the (London) Metropolis Gas Act of 186o as the "standard candle" in photometry. Owing to its extreme brittleness, spermaceti re quires to be mixed with a small proportion of other material, such as beeswax.

Modern Candles.

The bulk of modern candles are made of paraffin wax (introduced about 1854), or stearine, or mixtures of these. The crude paraffin wax from mineral oil refineries is "sweated" in ovens at a temperature slightly below the required melting-point to free it from lower melting waxes and traces of oils, and is subsequently purified by steaming with animal char coal and fuller's earth. As pure paraffin wax becomes plastic at temperatures considerably below its melting point, candles made from it are apt to bend, and it is usually stiffened with from 5 to s o% of stearine, which also makes the wax less transparent. Candles made from this mixture are known as "composite candles." The proportion of stearine is largely increased in candles intended for use in hot climates, and they may even be made entirely of stearine.Ceresin, the hydrocarbon derived from ozokerite, or earth-wax, is also used as a candle-stiffener.

The manufacture of stearine is based on the researches of Chevreul, who, in 1815, showed that fats consist of fatty acids combined with glycerin. The glycerin must be removed, for, on incomplete combustion, it gives rise to the formation of acrid vapours, as may be noticed when a tallow candle is allowed to smoulder. The solid fats, tallow, palm oil and bone fat are split into fatty acids and glycerin (hydrolysed) by the following proc esses. In the autoclave process, which is used for good quality fats, the material is churned with water and 3-4% of lime or mag nesia, with steam at 120 lb. pressure. The mixture separates into two layers—the glycerin "sweet-water" and a mixture of lime soap and fatty acids above. The lime soap is decomposed with dilute sulphuric acid and the washed fatty acids crystallized. The solid "stearine" is freed from the liquid oleic acid by pressing in a hydraulic press. In the acid saponification process, the fat is treated with 4-6% of concentrated sulphuric acid and hydrolysed with open steam. The resulting fatty acids are dark coloured and must be distilled with superheated steam before pressing. The yield of stearine is greater by the second process (6o%) , as the action of the acid converts some of the oleic acid into solid products. The Twitchell process, which consists in boiling the fat with half its bulk of water and a small proportion of a special emulsifying reagent, is suitable for low-grade fats. The fatty acids can be bleached by distillation.

Candle

Wicks.—The wick is one of the most important factors in candle-making ; unless it is of the size and texture proper to the material used, the candle will be unsatisfactory. The material generally employed is cotton yarn, which, except for tallow dips and tapers, is braided by machinery into an ordinary flat plait and "pickled." This process, invented by Cambaceres in 1825, consists in impregnating the fibre with a very small quantity of mineral matter which helps to fuse the ash of the wick and pre vent smoking. After a preliminary bleaching, the wick is soaked in a pickling solution of boracic acid and nitre, or sal ammoniac, or phosphate, or chlorate of ammonia, centrifuged to expel the bulk of the retained solution and dried. It is essential that the wick should be burnt in one direction only. Early wicks, which were not plaited or pickled, did not bend over to the outer oxidiz ing region of the flame and consequently were incompletely con sumed, the char requiring to be removed by frequent "snuffing." Tallow candles (dips) are manufactured on a commercial scale by the old "dipping" process, each dip adding about one-eighth inch to the diameter of the candle. Tallow dips are principally used by plumbers as a flux, and a considerable quantity by cer tain African natives for anointing.The dipping process is unsuitable for beeswax candles ; owing to the wax's property of contracting on cooling and its liability to stick, moulding is impracticable. Recourse is had to the some what primitive method of "pouring" the melted wax over a sus pended wick until the required thickness is obtained. The candle is then rolled on a marble slab to impart uniformity of finish. The difference of the two processes is illustrated by the existence of two Livery companies in the City of London, the Tallow Chandlers and the Wax Chandlers.

Moulded Candles.

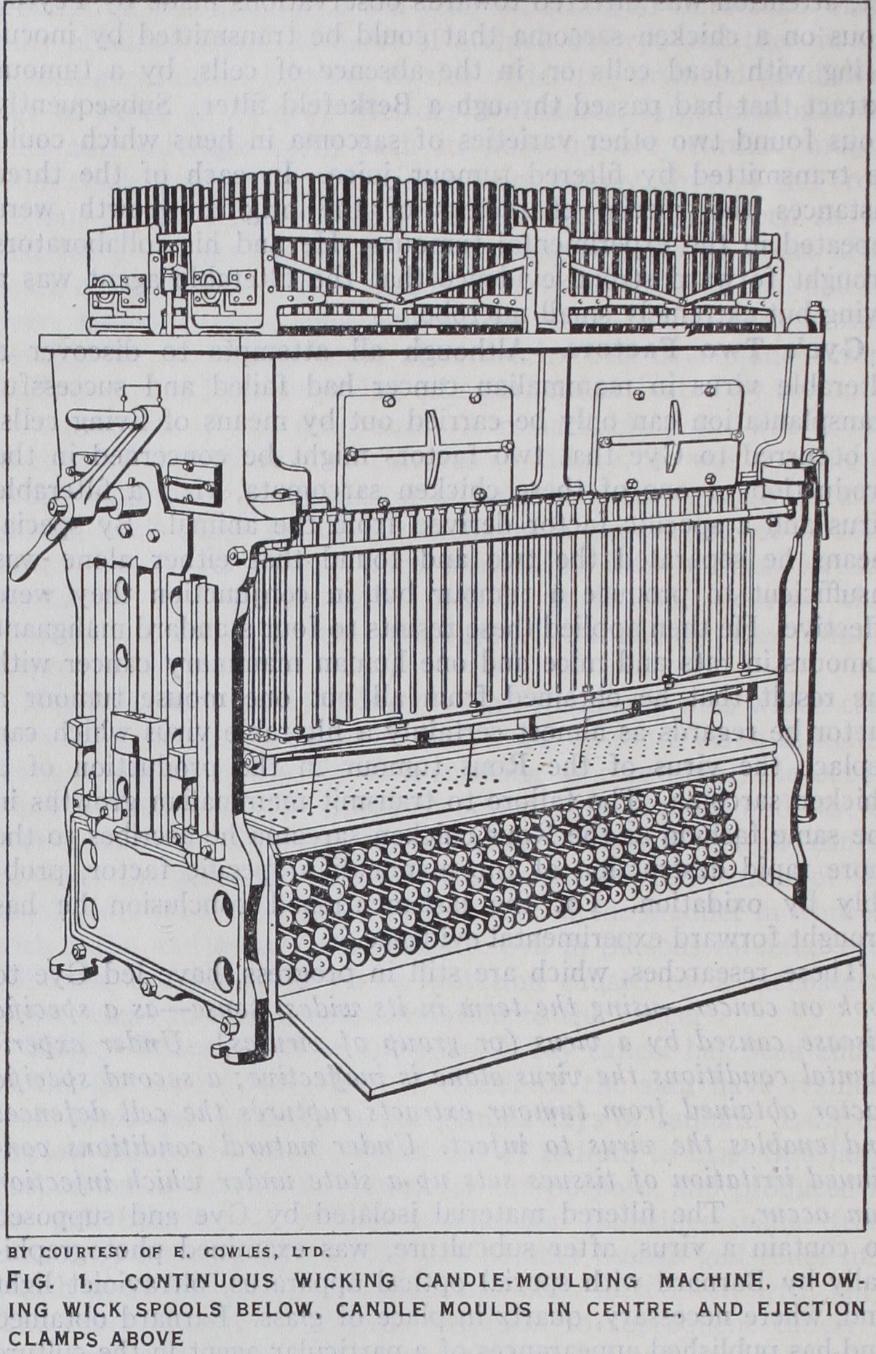

Moulding machines of the continuous wicking type, first made by Morgan in 1834, are used for the bulk of candle-making. Machines are made to produce from 8o to 552 candles at one charge, and the output is from two to three charges per hour. The machine consists of tubular moulds (slightly tapered to facilitate ejection of the candles), fixed in a tank to which steam or water can be admitted. The lower ends are closed by the tip-moulds which are carried each on a hollow piston-rod connected to a common bed-plate. The upper ends (butt-ends) open into a shallow trough. The moulds are made of tempered tin (g8% purity) and the inner surfaces are polished. Above the apparatus are the "clamps" to hold the candles when ejected from the moulds. The spools of wick, one for each mould, are con tained in a box under the machine. The wick is threaded through the piston, through a perforation in the centre of the tip-mould, and passes up the mould to be held centrally by the candle last ejected into the clamp. The moulds are heated to the required temperature and the molten terial poured in, leaving excess in the trough. The candles are then cooled by filling the tank with cold water, the wicks cut at the top and the clamps tied. The superfluous wax in the trough is scraped out, the plate screwed up, and the candles ejected into the clamps. The temperature of the moulds before filling and the speed of cooling have to be varied according to the material being moulded.

Night-lights.

S h o r t thick candles designed to burn six to ten hours, formerly made of coconut stearine, but now usually of a low-melting paraffin wax, are moulded similarly but without a wick; the latter, stiffened by a coating of hard wax, is subse quently fixed in a hole drilled through the wax cake. Great care is taken to avoid access of dust or dirt to the wax, as, since the flame is very small, the wick is easily clogged.

Tapers.

Tapers are made by "drawing" long strands of slightly twisted cotton yarn repeatedly through a bath of molten wax. The tapers are cut to length, the ends dipped in hot water and shaken. This process, called "feathering," removes the wax from one end, allowing a new taper to be lit easily without dripping wax. Small "birthday" and "Christmas" candles are made by this process, and also the "bougies" used in metal casting.On the continent a candle with an air-passage down its length, supposed to minimize guttering, is popular.

Ornamental candles are made of wax stained with aniline dyes and decorated with transfers or by handwork.

A hot-flame, smokeless candle, giving very little light, made from the esters of amino- or imino-acids together with a small quantity of an oxidizing salt such as ammonium nitrate, has been patented in Germany.

See J. Lewkowitsch, Oils_ Fats and Waxes (1923) ; L. L. Lamborn, Soaps, Candles and Glycerine (New York, 1906) ; Sadtler and Matos, Industrial Organic Chemistry (5923) ; Groves and Thorp, Chemical Technology, vol. ii. "Lighting" (1895) (for history) ; Catholic Encyclo pedia (for ritualistic use) . (E. L.; G. H. W.)