Carpet Manufacture

CARPET MANUFACTURE. Modern carpet manufacture involves the use of machinery and of many different materials, such as woollen and worsted yarns for the surface of the carpet, and cotton, linen and jute for the back. The wool which is most suitable for carpet yarn is generally fairly long in the staple and rather coarse than fine. It is obtained from Scotland, China, Thi bet, India, Russia, Australia, New Zealand, Egypt, Iceland and the East Indies. It can be spun into yarn of any required thickness, dyed to any shade, and woven into any fabric ; therefore it is an ideal material for the surface of carpets, especially as it retains its appearance and withstands reasonably hard wear.

Silk carpets are very beautiful, possessing a wonderful sheen, but they get soiled more quickly and have less resilience than wool carpets of a similar quality; and this, combined with their high cost, makes them luxuries for the few.

Cotton is used for chain warps in all kinds of carpeting, and forms the chain of Axminster and weft of Wilton and Brussels carpets. Flax yarn is sometimes used as a weft yarn in Brussels and Tapestry. Jute and hemp are used in considerable quantities as a filling, to give body or weight to the carpet, and as a weft in Axminster.

Other materials used occasionally in the manufacture of carpets are mohair, cowhair and horsehair for the surface of the carpet and ramie for the back. Twisted paper yarn has been tried for chain or "stuffer." Dyeing.—Dyeing plays a most important part in carpet manu facture, as practically all yarns used on the surface have to be dyed ; and fast colors are essential.

The yarns are impregnated with the oil or grease which they received during the process of spinning. Washing is then a neces sary preliminary to dyeing, as the presence of grease would prevent the dye permeating the fibers. Scouring is effected by soap and hot water, and passes, without being fully dried, to the dyeing machine.

The

process of dyeing the yarn in skeins is generally effected by mechanical means and is similar to that adopted in other branches of the textile trade. (See DYEING.) Hand-made Carpets.—The main classification of carpets is between those which are made by hand and those which are made by machine ; and of these classes, especially of the latter, there are many subdivisions.Hand-made carpets are the oldest type, and are the historical par ents of all modern carpets. This kind of carpet is made to-day in the United Kingdom, on the Continent, and in the East in almost exactly the same manner in which it has been made by the Ori entals for several hundred years. The principle is extremely sim ple. The warp threads, or chain, are wound on two horizontal beams, between which they are stretched vertically. The beams are carried by upright posts on which they can revolve, the space between the posts determining the width of the rug or carpet. The weavers sit side by side in front, the carpet as it is woven being gradually wound on to the lower beam and the warp correspond ingly unwound from the upper beam. The yarn for the pile is cut about tin. in length and is knotted round two warp threads, tuft by tuft, according to the paper design, in front of the weaver. As each row, or part of a now is finished, two weft threads are put in, one in the shed formed between the front and back halves of the chain, and a second in an alternate shed, which is formed by the weaver pulling forward the back half of the chain temporarily in front of the front half. The second weft is put in straight, the first one loose, zigzag or vandyked, so as to fill up the back of the car pet and to avoid the tendency towards lateral contraction. The weft is beaten down into its place by a heavy fork or beater. This interlocking of warp and weft with the tuft forms the weave of the carpet, and has been imitated more or less in all mechanically woven carpet fabrics. There are two different kinds of knot em ployed, the Ghiordes or Turkish, and the Senne or Persian; the tufts of yarn in the former coming in pairs between the two warp threads (fig. I, A) and in the latter coming singly between each warp thread (fig. I, B). In either case the tufts do not stand up vertically to the plane of the fabric but lie over obliquely towards the starting end of the carpet.

This presents to the eye and foot of the user partly the ends and partly the sides of the tufts, and is a very characteristic fea ture of hand-made carpets.

Another kind of hand weaving is the tapestry method, wherein the weft colours, wound upon wooden needles, are threaded round and between the warp ends, leaving a flat or slightly ribbed surface, not unlike that of an ingrain carpet. The absence of a tufted pile does not make this a luxurious carpet, but it enables a fine pitch to be employed and the richest and most delicate effects of design and colour to be obtained. Carpets of this type have long been made at Les Gobelins, Paris, Aubusson and Beauvais in France, and Tournai in Belgium. The work is slow and highly skilled, and the product is naturally very expensive.

There is no better carpet than that made by hand ; though this is far from implying that all hand-tufted carpets are superior to all machine-made ones. The hand-tufted carpet possesses an indi viduality, even in its faults, which no product of a machine can attain; and which, after all, is an attribute of a work of art.

Hand-made carpets have a further advantage in their adapta bility to requirements. A single carpet, for instance, can be made to any specified shape, size, design, colour and quality. It is pos sible to produce in one piece carpets of oval, circular or L-shaped form, or to conform to irregular curves and angles.

Qualities are numerous, but they may be said to vary between about 9 and 400 tufts to the sq. inch. The average European hand-made carpet will not run to more than from 16 to 3o.

The principal seats of the Oriental hand manufacture of carpets are India, Persia, Egypt, Turkey-in-Asia and China; to which countries may perhaps be added Greece, to where, since the World War, a certain amount of the Turkish carpet industry has been transferred.

In

Persia the chief centres are Kerman, Feraghan and Kurdi stan; each of which produces carpets of characteristic patterns and qualities.Turkish carpets are, broadly speaking, of coarser texture than Persian. The typical Turkey carpet comes from Ushak, but the industry extends over many parts of Asia Minor.

Carpets are also made in Tripoli, Tunis and Algiers.

The manufacture of carpets is widely distributed throughout India in the localities of Mirzapore, Benares, Masulipatam, Kash mir, Multan, Amritzar and Peshawar; while rugs of a cheaper type are made in Bengal. Indian carpets generally are less fine in fabric, as well as in design and colour, than Persian.

The European, or Occidental, branch of the trade is located in Maffersdorf (Czechoslovakia), Holland, Donegal, Carlisle, Wilton and the Balearic islands.

European hand-tufted carpets may be regarded upon a differ ent footing from Asiatic, inasmuch as, although in the localities named, carpets of characteristic Eastern design and colouring are produced, their staple trade has always been rather along the lines of specialties ; and the makers have catered rather for architects, decorators and public bodies than for the average consumer.

In the East, the weaving of carpets has long been and is still largely a family affair. The women and children sit in front of the loom, and work under the supervision of the matriarch. Obviously the degrees of skill employed will vary; and this leads to some of the irregularities in Eastern carpets. It is not to be implied, how ever, that all Oriental carpets are still the product of family or tribal industry. Western methods have penetrated even to the "unchanging East"; organization of the industry has been set up; and carpet dealers' and importers' syndicates in New York, Lon don and Paris have their agents in the East and even control their own factories.

It is a common fallacy that the yarns of Oriental carpets are dyed solely with vegetable dyes, and that those dyes are intrinsi cally superior to aniline and alizarine dyes such as are employed for yarns for machine-made fabrics. The latter have been used for many years now by European carpet manufacturers, not be cause they are cheaper than vegetable dyes, but because they are easier to use, more accurate for matching purposes and faster to light. There are, of course, good and bad synthetic dyes; but the best are immeasurably superior to dyes made from plants, barks and berries. This fact has long been recognized by those who con trol the production of Oriental carpets, for the yarns for which aniline and alizarine dyes are now extensively employed.

The

subject of dyeing naturally leads to that of the so-called "washing" or "faking," to which a large proportion of Eastern carpets are submitted. The object of this is twofold; to soften the colours and to give an appearance of age, and to obtain a gloss which the wool does not naturally possess. The process in volves the use of chlorine or acetic acid to give the faded effect, while glycerine and ironing are employed to get the glossiness. It can hardly be supposed that this treatment does not detract to some extent from the life of the carpet ; but this consideration appears to be outweighed by that of the more attractive appear ance. The process has been tried upon Wilton carpet, but with doubtful success.

Brussels Carpets.

Of machine made carpets, Brussels is nat urally first to be mentioned, as it was the first to be made in Europe. It is a loop-pile fabric, having a strong foundation of linen, jute and cotton yarns, together with that portion of worsted yarn which is not utilized on the surface to form the pattern. The pattern itself is formed by differently coloured threads of worsted yarn looped over a wire. The body and back of the carpet is provided for normally by two warp beams, called the chain and the stuffer. The chain is usually of cotton, and its object is to form, in combination with the weft, the woven base of the fabric. The threads of the two chains are led through eyelets mounted on heald-frames or gears, which rise alternately in such a way as to allow the shuttle carrying the weft to be shot through the opening thus formed. The purpose of the stuffer or "dead" warp is solely to give body or weight to the fabric.The stuffer threads are carried on eyelets in a frame, similar to the chain, but are not divided, and remain practically in the middle of the fabric. The worsted yarn, which forms the pile warp, is arranged on bobbins, in frames (generally five in number), and the threads are drawn through the harness, which consists of cords carrying eyelets, and kept taut by the weight below while con nected with the Jacquard mechanism above.

The Jacquard principle is well known throughout the textile trades, and is a device for selecting and raising the threads re quired to form the pattern. All the warp threads are drawn through the sley or reed in such a way that there will be in each reed-space five threads of worsted (for a "five-frame" carpet) , two of cotton chain, and one of stuffer. When the loom is run ning the Jacquard mechanism lifts one worsted thread in each reed, thus forming a shed under which the wire is introduced from the side. Underneath the wire lies the body of the fabric, consist ing of the four other worsted threads in each course, the stuffer warp, and one-half of the cotton chain warp. Below the body of the fabric is the lower shed formed by the other half of the cotton chain, and through this the shuttle passes, carrying the weft at the same time as the wire is being inserted. Then the lathe, which has been lying back to allow the passing of the shuttle and the entrance of the wire, comes forward with the sley and beats up the wire and the last shot of weft against the breastplate of the loom and the last part of the woven fabric. At the same time the Jacquard allows the harness carrying the ends selected for the last lash to drop back on to a level with the others, and the gears carrying the cotton chain begin to change. Next, the lathe goes back again ; one half of the chain is brought up to form a shed, under which and over the rest of the threads the shuttle passes back, thus effec tively tying in the worsted threads which are looped over the wire.

Brussels and Wilton carpets are described as being 5, 4 or 3 frames, according to the number of sets of creol bobbins carrying worsted warp threads. (See fig. 2.) The demand for all qualities of Brussels carpeting has declined steadily for many years, as the fabric has suffered from the competition of Axminster and of Tapestry; being essentially less economic in manufacture than either of these. A good Brussels, however, is an excellent carpet, and will last for many years.

After leaving the loom the roll of carpet is measured, dried, "picked" or mended, shorn, inspected, and sometimes pressed.

Wilton Carpets.

Wilton carpet is similar in manufacture in many respects to Brussels, and the looms are in practice converti ble from one fabric to the other without much difficulty. The preparation of yarn is substantially identical, and the weaving and finishing operations very similar.The essential differences are:— In weaving Wilton the loops of worsted yarns are cut, so that the surface is velvety instead of being ribbed. This is effected by the use of a flat narrow wire ending in a knife blade, which stands outside the fabric when the wire is inserted but severs the loops of worsted as it is withdrawn. Many makes of Wilton, for the sake of holding down the pile more securely, have three shots of weft to each row of pile instead of two. The cutting of the yarn, which has the effect of exposing the ends instead of the sides of the wool fibre, gives a richer "plush-like" surface effect both in appearance and to the touch ; while the treble weft makes a firmer fabric. (Fig. 3.) The standard Wilton quality has a pile of about Ain. high and contains about 90 points to the sq.in. ; but the fabric lends itself readily to fine and luxurious effects, and there are qualities made with a deeper pile and of a fineness of about 120 to the sq. inch. Cheaper qualities are also made with a woolen pile yarn of a coarseness of about 6o to the sq.in., but these qualities do not compete very effectively with the more attractive Axminster at about the same cost.

Wilton carpets, like Brussels, have two limitations—one eco nomic and one artistic. For every square of the pile warp showing on the surface there are two to five parts uneconomically used in the body of the fabric; and the number of "frames" that can be worked one over the other to form the pattern is limited to six. These limitations, however, are not serious ones; and the Wilton carpet in its higher grades is regarded by many as the best of all machine-made carpets. It is certainly the finest ; and the closeness of texture, broadly speaking, means both finer effects and better wear.

The higher grades of Wilton are made from 95 to '28 points to the sq.in. ; so that, in the matter both of delicacy of design and of texture, effects can be produced in Wilton which surpass those of any other carpet fabric, with the exception of the finest Persians.

Axminster Carpets.

An Axminster carpet presents a some what similar appearance to a Wilton carpet, but the essential dif ference between the two fabrics is that the surface of the former is composed of tufts inserted in the fabric, while the surface of the latter is formed by cutting the pile warp threads.Axminster carpets, though in point of time a comparatively re cent development of the industry, may claim to be, in point of structure, the nearest related of all machine-made carpets to the Oriental ancestor. The similarity lies in the fact that they are tufted; and the tuft, though inserted in the fabric mechanically and bound down without being knotted, undoubtedly represents the knotted tuft of the original hand-made carpet. The essential feature of a tufted Axminster carpet is that the tufts are inserted row by row between the warp threads, either before or after being cut off, and are then bound down by the weft, and so woven into the ground of the texture. Each tuft is used on the surface and forms part of the design ; none of the tuft material is buried or wasted in the body of the fabric, beyond what is needed for attachment to the weft.

As in other carpet fabrics, there are various qualities of Ax minster carpeting, the most popular is made in a pitch of 7 to the inch, with a beat-up of about 64; giving 45 tufts to the sq.in., each tuft being about $in. high. Fig. 4 gives the transverse section through the weft of the weave ordinarily employed, though there are several variations, of which another is shown in the same fig ure. The figure forms a flat back and gives the tuft a distinct in clination out of the vertical, adding a point of similarity to the hand-tufted carpet ; and the latter figure gives the back a ribbed appearance, the tuft in this case remaining vertical.

Each of these two named weaves has its merits. The former gives better cover with its sloping tuft, while the latter claims increased resiliency and immunity from the shading in made-up carpets, so noticeable with the first-named weave.

Axminster manufacture consists of two processes, the pile yarn being arranged to form the design before it is put into the loom. The dyed yarn of the various colours for the design is first wound on to a 6in. bobbin. The yarn from this bobbin has then to be wound on to a series of wide spools, the number of which will be the number of the rows of tufts in one complete repeat of the de sign to be woven, while each spool contains as many ends of yarn as there are squares in the width of the design. This operation is called setting, or sometimes reeding-in. The 6in. bobbins are arranged on a frame on vertical or horizontal pegs in their various colours, corresponding to those of the first row of the design. The yarn is then wound off the bobbins on the 27in. spool, and when the spool is full the operation is repeated as often as is necessary of the chain warp. In this position they are tied down by the pass ing of a weft shot, and are then cut off by a pair of broad knives working at the level of the surface of the carpet. The spool and carriage are then replaced on the chains, and the succeeding spool brought into position (fig. S).

Another method of the Axminster principle of inserting tufts into the weave of the fabric is that of conveying tufts already cut by means of gripper or nippers. This is sometimes worked in com bination with the wide spools, but more satisfactorily in combina tion with yarn carriers operated by a Jacquard with a differential lift mechanism for selecting the colours. In this case the yarns are placed on bobbins in frames as in the Brussels or Wilton looms, and then led into carriers which are grooved and slotted metal strips. The slots are fitted with springs which hold the threads of yarn one above another, presenting their ends to the front of the for weaving the required quantity. Then the bobbins are re arranged for the second row of the design and so on.

The yarn on the wide spools is then threaded through a series of tin tubes, the number of which corresponds with the number of ends on each spool. The tufting carriages are then pjaced, in the correct rotation to form the pattern, upon a pair of endless chains, which are actuated by the mechanism of the loom. The wide spools and carriages are then successively detached from the chains and carried down to the fell of the cloth in such a way that the ends of the tuft yarns are inserted between the upper shed loom. The Jacquard mechanism causes the colour required for each square of the pattern to be lifted to a certain height. The grippers, mounted on a shaft, are operated so as to seize the ends of the tufts, which are then cut off and inserted at the fell of the cloth between the chain warp threads, where they are tied down by weft shots.

Chenille Carpets.

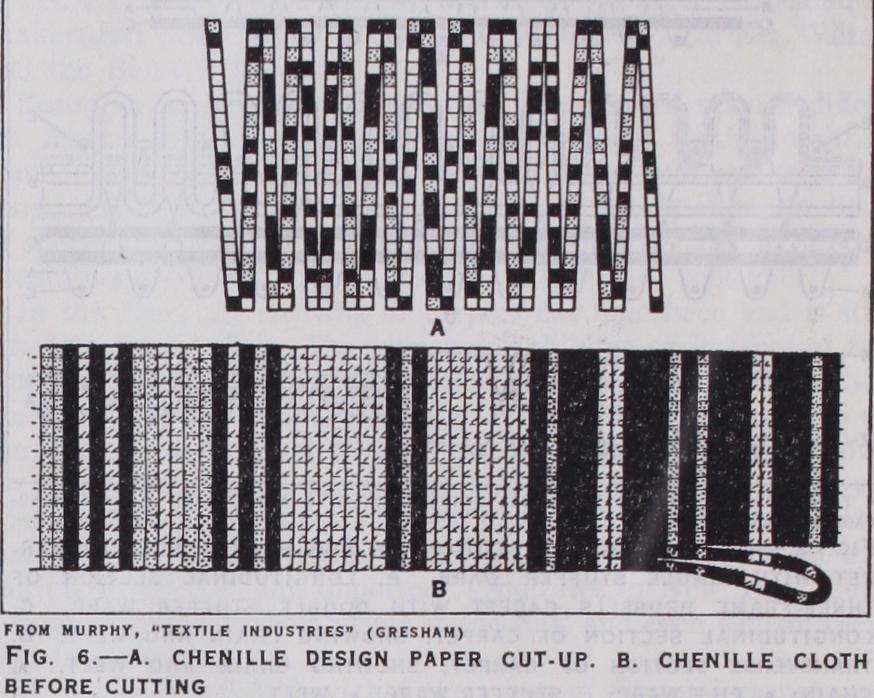

Chenille Axminster carpeting possesses features which differentiate it from the other kinds of carpets. Like Orientals, it can be woven to any width, up to 33ft., any reasonable length, any shape, and of any design or number of colours. It is the product of two distinct processes; the formation of the chenille fur, and the weaving of that fur, which is the weft, into a carpet. It is, in fact, about the only cut-pile carpet fabric in which the pattern is distinctively formed by the weft; for in almost all other makes the weft only performs the function of combining with the chain to form the woven fabric.The dyed yarn, which is generally woollen, is wound on to cops which fit inside shuttles for the weft looms. The paper design to which the weaver has to work is cut up into strips two squares wide (fig. 6a), and the weaver at taches this strip to the fabric as it is woven and changes the shuttles carrying yarn of various colours in accordance with the colours on the design paper. The warp of the loom consists of sets of ends of fine cotton at inter vals of from half-an-inch to an inch, according to the pile de sired. Thus the woven fabric con sists of a woollen weft of various colours held together at intervals by a fine cotton warp (fig. 6b).

The next process is the fur-cutting. The roll of cloth with its horizontal stripes is taken to the cutting machine, where it is cut into strips by a series of knives set upon a revolving cylinder and spaced so that they sever the woollen weft-threads between the cotton warps as the fabric passes over the cutting bed, and leave the independent strips of fur held together by the fine cotton warp.

Immediately after being cut free these strips of fur pass over a jet of steam and steam-heated cylinder, whose surface is formed with a series of V-shaped grooves. This has the result of folding up wards the cut ends of the woollen yarn and giving a permanent V-shape in section to the fur. The object of this is that when the fur comes to be woven its pile shall be turned in one direction.

The damping of the fur just before passing over the grooved cylinder is sometimes effected by rollers revolving in a trough filled with water (fig. 7) . The newly formed fur is then reeled off into individual skeins. It is marked both with its pattern num ber and series number and sorted into its proper sets.

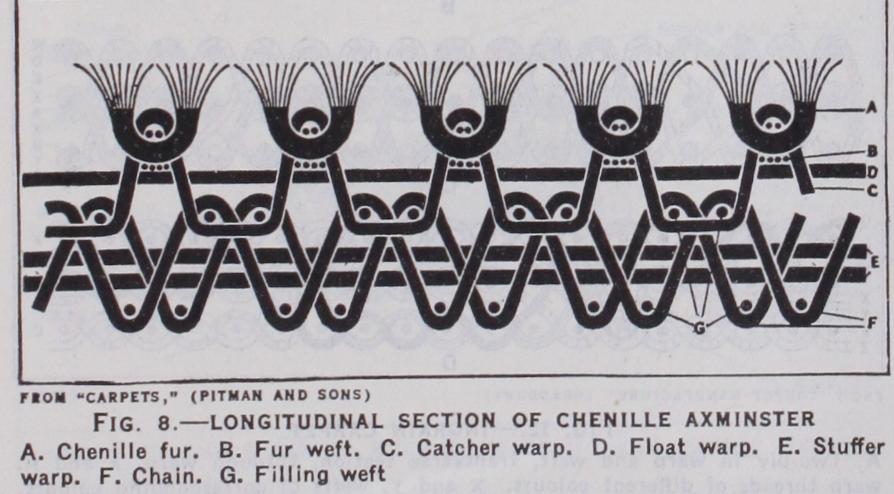

The second part of Chenille manufacture is the weaving of the fur into the carpet, which is done on what is known as a setting loom. The warp of a setting loom consists of chain and stuffer, as in the Brussels and Wilton looms, while sometimes an addi tional one is used, called the float warp. There is also the catcher warp, which is of fine strong cotton. Its function is merely to hold down the fur weft when it is inserted into the fabric. Be sides the fur weft, there is the jute or coarse woolly filling weft, of which there are four shots to each one of fur. (See fig. 8.) When a carpet is to be woven the fur is wound into cops, which are served out to the weaver in their proper order. The shuttle carrying the fur weft is shot across the loom below the catcher warp but above all other warps. The loom stops automatically, and the weavers (two to each wide loom) set the fur with combs, taking care that the design matches correctly with the previous shot, and that the catcher threads settle down neatly through the pile. The loom is restarted and the four shots of filling weft in serted. Alternatively the fur may be inserted by a travelling arm, operated between the catcher and the other warps, which leads the fur from a basket or can. Chenille carpets have become very popular since their introduction, partly of course owing to this fabric being the first with a cut pile to be applied to the manu facture of wide carpets in one piece ; partly to the wide range of colours that can be employed; and partly to its comparative cheapness.

Tapestry Carpets.

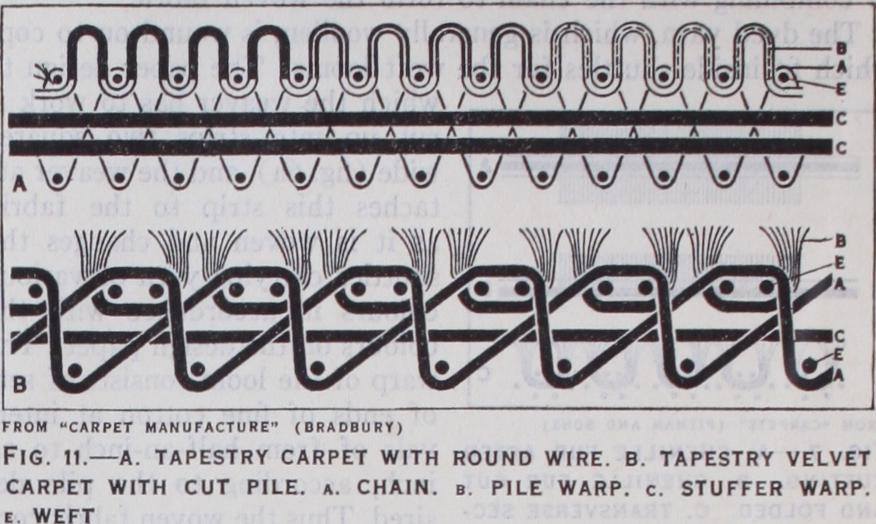

Tapestry is a fabric made alternatively with a looped pile or a cut pile, called Velvet, which possesses a close affinity to Brussels and Wilton respectively in its appearance and texture. In its method of manufacture, however, it has something in common with nille, inasmuch as it is essentially a two-process fabric, while the pattern is wholly in the surface and is the direct result of the liminary and not of the weaving process. No Jacquard is used.The underlying principle of the fabric is the attainment of econ omy by the use of one frame of worsted yarn on which the pat tern is printed in its various col ours instead of dyeing five frames of yarn, each of a different colour. The worsted can be coloured be fore or after the weaving, and in the former case, which is the standard method, it is printed in an elongated form to allow for the reduction caused by the inser tion of the wires in weaving (fig. 9). The yarn is wound on to a large drum from i s f t. to 4oft. in circumference and with a face of from i8in. to 7 tin. ; and the colour is applied by means of a carriage bearing a colour-roller, which is drawn across the face of the drum pressing upon the yarn threads. The printer changes the colours in accordance with the design paper and the "scale board." When the printing is fin ished the yarn is scraped, removed from the drum, looped and tick eted in rotation to show the place each thread occupies in the de sign. The colour is then fixed by being steamed, and the yarn is rinsed and dried. The yarn is wound on to large bobbins, duly numbered, and thence on to a warp beam of the width of the fabric to be woven. The "setters" arrange the threads so as to form the pattern, which is still in its elongated form (fig. ioa), but which assumes its correct shape when woven (fig. iob).

The method of weaving is substantially the same as with Brus sels and Wilton, the wires being round for Tapestry or provided with knives for the Velvet (fig. I 1).

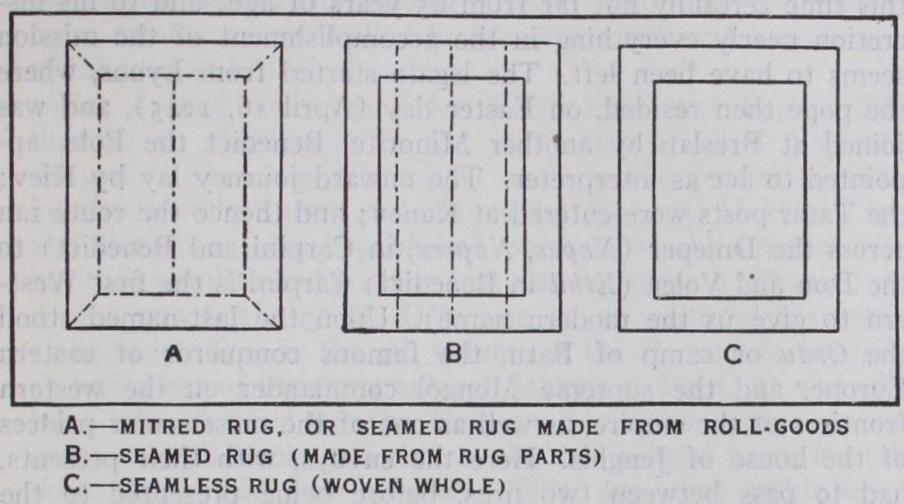

The demand for Tapestry and Velvet carpets has changed, as with other fabrics, from piece goods to breadth squares and on to seamless squares, with a corresponding increase in the cost of man ufacture, for the Tapestry and Velvet carpet can only be produced economically if in large quantities.

The chief disadvantage of these fabrics is that the transition from one colour to another in the same length of worsted cannot be made quite suddenly, so that in the design the colour will ap pear to have run, and the clearly defined pattern effect of Brussels and Wilton is unobtainable. Apart from that, Tapestry and Vel vet have much to commend them. They can be sold at moderate prices, and are capable of a wide range of effects in design and colour, circumstances which have given them a considerable measure of popularity with the public.

Ingrain Carpets.

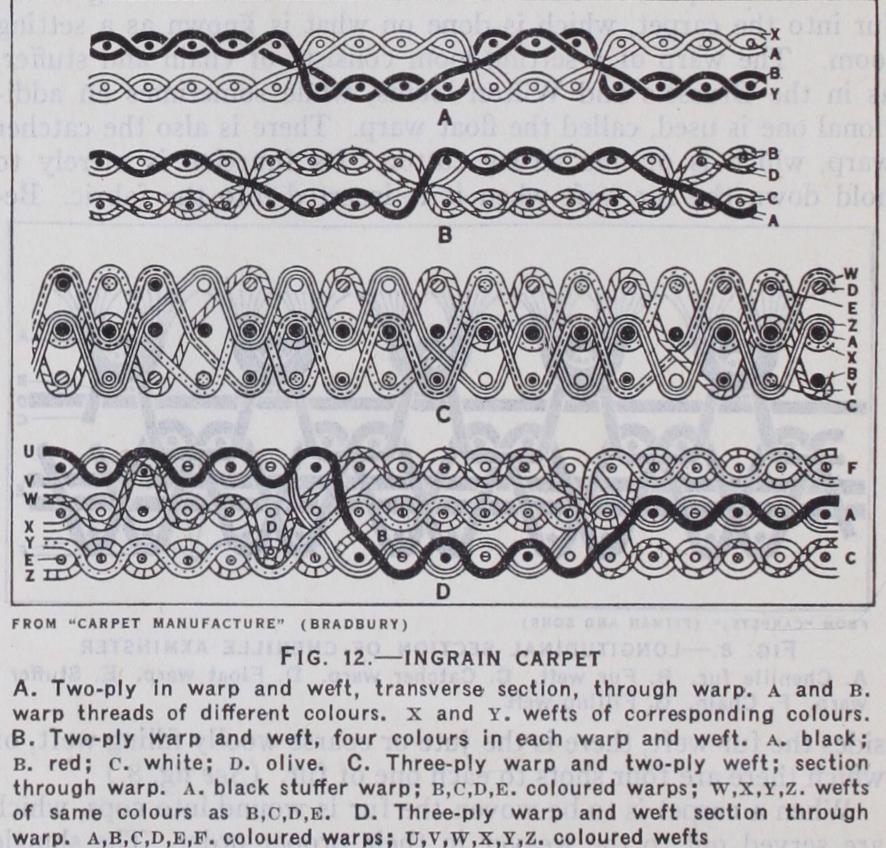

The kind of carpet that is variously called Kidderminster, Scotch or Ingrain differs considerably from any of the carpets hitherto described. Perhaps essentially, and in regard to texture, it is most akin to hand-woven Tapestry, having a flat ribbed surface, without tufts like Axminster or loops like Brussels.The original type of this carpet was the Ingrain or "Two-ply Super." It was made with a worsted warp and a woollen weft in 36in. width (fig. 12a).

Developments have been made in vari ous directions, but principally in those of heavier fabrics and wider looms. Addi tional colour effects are obtained by in creasing the number of warps and of wefts, while heavier fabrics are made "three-ply." (See figs. 12b, c, d.) The yard wide Ingrain is now almost extinct, and the modern form of the fabric is the so-called Art Square, a fairly heavy seamless carpet, generally produced in bold and simple effects of design and colour.

Compared with some carpet fabrics, Ingrain must take a modest place. It cannot be regarded as luxurious to tread upon, its flat surface lacking the resili ency which the looped or cut pile gives to even a cheap Brussels or a Tapestry velvet. On the other hand, it is capable of giving artistic effects, within its limits, and the fabric is clean in wear and easily handled.

Modern Developments : Wide Looms.—The exact date cannot be fixed; but from about the first decade of the loth century a demand began to be evinced in the carpet markets of the world for carpets made without seams, and manufacturers began to set them selves to meet the demand. Hitherto, seamless carpets had, broadly speaking, only been available in hand-tufted fab rics, in Art Squares, and in Chenille ; but thereafter there was a speedy develop ment in other machine-made fabrics.

Wilton.

Looms of 9ft. in width and upwards were constructed in both the United States and in Great Britain on the same principles as the 27in. loom, and worked with fair success ; although the expense, both of construction and of op erations, made the fabric costly out of proportion to the narrow goods. In par ticular, the withdrawing of the wire at the side necessitated the total width of the loom being more than double the width of the fabric woven and slowed down the rate of production considerably. To over come these objections a loom was devised in the United States in which the cutting of the loops was effected by a series of knives placed across the carpet parallel to its length. Looms on this prin ciple have been brought to something like perfection and are being operated in Great Britain and in the United States with success; while other wide looms are being run both in these countries and on the Continent.Axminster.—Similarly, the tube principle has been extended from the 27in. width to widths of 9ft. and more, and the gripper principle, combined with the Jacquard, has had a like develop ment. The most striking departure, however, of the Axminster principle has been a wide loom which produces mechanically a fabric in which the tufts are tied with a Ghiordes knot, exactly as in the Oriental hand-looms. This loom was introduced into Kid derminster in 191o, and has been brought to a high pitch of effi ciency. The fabric is made in various qualities up to 49 tufts per inch.

Tapestry.

This fabric has followed the same lines of develop ment, and many wide printed fabrics, especially with the cut pile velvet, are being produced on the same principle as the narrow weave.

Design and Colour.

There was a time when the phrase "flam ing Brussels carpet" was not entirely undeserved, but this has long passed. The naturalistic and geometrical styles, both brightly col oured, passed away, partly under the influence of William Morris, who introduced, and of others who developed, the conventional style of decoration in carpets.The carpet trade then passed into an era of reproduction, the masterpieces of Oriental and, in particular, of Persian art being studied and carefully copied. The next stage in the development of carpet design was the drawing of inspiration from the char acteristic decorative styles of other countries and ages; first China and Japan, then France; the periods of Louis XIV., Louis XVI., and of Rococo, Renaissance, Empire. The ancient art of Egypt, Crete, Greece, Assyria and Rome was laid under contribution, and with creditable and interesting results which have proved healthy and stimulating for the industry. Finally, the Cubist or Futurist or Modern movement in the world of art has not been without its influence on carpet design, to which indeed the flat and bold treat ment of decoration is very suitable. In the result, therefore, it may be said that there is a cosmopolitanism and an eclecticism of taste in carpet design at the present day; and a good pattern of whatever style, provided that it be true to the style and that it be well coloured, whether quietly, brightly or richly, is sure of acceptance.

Carpet Statistics.—In Germany the industrial census of 1925 gives the number of carpet factories as 1,016, and of workers as 15,265, of whom 6,297 were female. The chief localities of the in dustry are Barmen, Elberfeld, Daren, Chemnitz, Leipzig, Berlin and Cottbus ; but there are many small concerns scattered throughout the country.

A large number of carpet factories is given in a French trade directory of 1926, but the majority of these are small concerns making hand-tufted carpets. The most important centres are Roubaix and Tourcoing for machine-made goods, and Aubusson, Beauvais and Felletin for hand-tufted. Nimes, Halluin, Lannoy and Persan are also centres.

In 1913 the value of production was estimated at 2 5,00o,000f rs. No post-War figures are available, but in 1926 France exported 16,925sq.in. of knotted woollen carpets to the value of 5,747, 000f rs. and 23,124 metric cwts. of other woollen carpets, to the value of 1 o i ,o61,000f rs. No reliable figures are obtainable as to the number of workers now engaged in the industry.

The principal centres of the carpet trade in Great Britain are in the south of Scotland (about 25%), the north of England (20%) , and Kidderminster (40%) . There are about 4,500 looms of var ious kinds and widths in the whole trade, of which number Wilton, Chenille, Tapestry and Axminster contribute together equally about 95%, the balance being ingrain and hand-tufted looms. The total number of employees in 1927 was about 37,00o, of whom rather more than one quarter were male.

The total production in the United Kingdom in 1924 was 21, in the following proportions :—Tapestry 31%, Brussels and Wilton 16%, Axminster (tufted and chenille) 45%, hand-tufted and other n.e.s. 6%. The value was £9,844,000 in the following proportions :—Tapestry, 16%, Brussels and Wilton 22%, Axminster 55%, ingrain 1%, hand-tufted and others 6%.

The imports have increased from 6o5,181 sq.yd. of the value of £1,168,o55 in 1919 to 5,684,859sq.yd. value in 1927; figures which are ominous for the future of the British carpet manufacturing industry. The exports in 1920 were 6,921,400sq.yd. valued at £4,544,376; and in 1926, 6,757,2oosq.yd., valued at £3,063,148.

In the United States there are 62 carpet factories. In 1927 the production amounted to 65,628,74osq.yd., and the number of workers employed was 32,29o. The chief centres of manufacture are Philadelphia, Pa., Amsterdam and Yonkers, N. Y., Worcester and Clinton, Mass., Freehold, N. J., and Thompsonville, Conn. The imports of oriental carpets into the United States in 1928 were See R. S. Brinton, Carpets (1919). (R. S. B.) In 1927 production in the American carpet and rug industry, according to the U.S. bureau of census, used lb. of wool and purchased 34,705,995 lb. of woollen and worsted yarn from independent spinners. The square yardage produced that year was : carpets 16,228,421, rugs, 49,400,310. This yardage was divided as follows : Chenille . . . 329,176 Axminster . .24,831,411 Velvet . . . 16,079,418 Tapestry . . . 6,41 0,441 Smyrna . Ingrain . . 265,609 Wilton . . . 10,266,199 All others . . Sixty-two manufacturers reported a total of 9,771 looms and a total production value of $164,709,290.00. For the calendar year 1928 the U.S. tariff commission reported 3,184,52o sq.yd. of woven floor coverings imported—mostly oriental rugs from Persia, Turkey and China. The exports have always been negligible and in 1928 the total yardage shipped, mainly to Mexico and Canada, was 124,600.

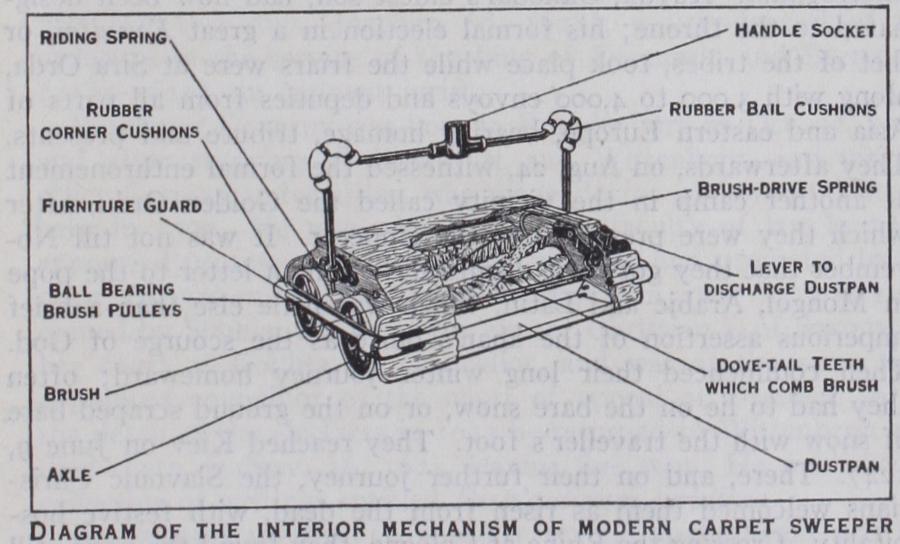

The first mechanical carpet-sweeper seems to have made its appearance sometime in the sixties. About 1865, a satisfactory sweeper was manufactured which consisted of a substantial cast-iron box, carried upon a pair of trans verse rollers, containing a roller-brush which derived its motion from a belt pulley which was fixed upon the projecting end of the rearward roller. The brush, by its rotation, was assumed to throw its sweepings into the box, which would subsequently be turned upside down and emptied. Owing to the weakness of the belt drive and the extreme resistance offered by the brush due to its compact formation as a roller, this machine swept imperfectly. Other carpet-sweepers followed during the next decade, all signed with a brush of the same close formation, and each creating for its ing apparatus the same difficulty of coming the frictional resistance of the carpet. In some, however, came the germ of the modern system which discards the belt pulleys and secures rotation by the friction of four rubber faced carrying wheels against the peripheries of drums which are fixed upon the brush.

There was still, however, the problem of the fully filled brush, and the sluggish movement which arose from its grip on the carpet. Succeeding designers, there fore, abandoned the brush with the roller surface and introduced one bearing some what the appearance of a paddle wheel, the bristle being set in four rows and so arranged in a waved or serpentine form, that while not more than five knots of bristle could grip the pile at any one time, the carpet was as fully covered in the course of a complete revolution as if the brush retained its former mass of closely packed material. Now, driven with less resistance and turned more swiftly by means of the rubber faced 'friction drive," the brush at last swept successfully, and thus gave an acceptable foundation for all the developments which have followed.