Carthage

CARTHAGE, one of the most famous cities of antiquity, on the north coast of Africa; it was founded about 814-813 B.C.

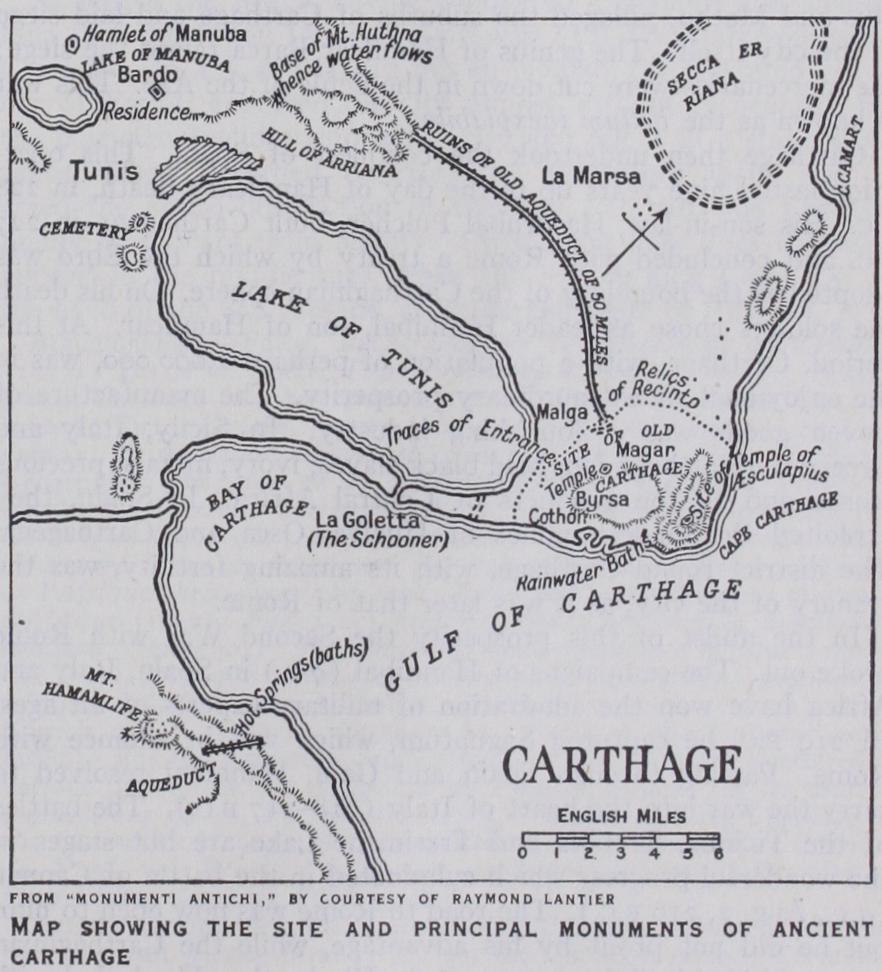

by the Phoenicians, destroyed for the first time by the Romans in 146 B.C., rebuilt by the Romans in 122 B.C., and finally de stroyed by the Arabs in A.D. 698. It was situated in the heart of the Sinus Uticensis (mod. Gulf of Tunis), which is protected on the west by the promontory of Apollo (mod. Ras Ali el Mekki), and on the east by the promontory of Mercury or Cape Bon (mod. Ras Addar). Its position naturally forms a sort of bastion on the inner curve of the bay between the Lake of Tunis on the south and the marshy plain of Utica (Sukhara) on the north. Cape Gamart, the Arab village of Sidi-bu-Said and the small harbour of Goletta (La Goulette, Halk el Wad) form a triangle which represents the area of Carthage at its greatest, in cluding its extramural suburbs. Of this area the highest point is Sidi-bu-Said, which stands on a lofty cliff about 490 ft. high. On Cape Gamart (Kamart) was the chief cemetery. The citadel, Byrsa, was on the hill on which to-day stand the convent of Les Peres Blancs and the cathedral of St. Louis, with a very inter esting archaeological museum, containing the results of the exca vations conducted by Pere Delattre, while the objects found in the excavations conducted by the Government are at the Bardo (see 'rums). The harbours lay about three-fif the of a mile south of Byrsa. The tongue of land, from the site of the harbours as far as Goletta, to the mouth of the Catadas which connects the Lake of Tunis with the sea, was known as taenia (ribbon, band) or ligula (diminutive of Lingua, tongue). The isthmus con necting the peninsula of Carthage with the mainland was roughly estimated by Polybius as 25 stades (about I s,000 ft.); the pen insula itself, according to Strabo, had a circumference of 36o stades (41 m.) . The distance between Gamart and Goletta is about 6 m.

From Byrsa, which is only 195 ft. above the sea, there is a fine view ; thence it is possible to see how Carthage was able at once to dominate the sea and the gently undulating plains which stretch westward as far as Tunis and the line of the river Bagra das (mod. Mejerda). On the horizon, on the other side of the Gulf of Tunis, rise the chief heights of the mountain-chain which was the scene of so many fierce struggles between Carthage and Rome, between Rome and the Vandals—the Bu-Kornain ("Two Horned Mountain"), crowned by the ruins of the temple of Saturn Balcaranensis; Jebel Ressas, behind which lie the ruins of Neferis; Zaghwan, the highest point in Zeugitana; Hammam Lif, Rades (Ghades, Gades, the ancient Maxula) on the coast and 1 o m. to the south-west the "white" Tunis ()twKOs T vvrls of Diodorus) and the fertile hills of Ariana.

Harbours.

The ancient harbours were distinguished as the military and the commercial. The remains of the latter are to be seen in a partially ruined artificial lagoon which originally had an area of nearly 6o acres ; there were, however, in addition a large quay for unloading freight along the shore, and huge basins or outer harbours protected by jetties, the remains of which are still visible at the water-level. The military harbour, known as Cothon, communicated with the commercial by means of a canal now partially ruined; it was circular in shape, surrounded by large docks I6-1- ft. wide, and capable of holding 220 vessels, though its area was only some 22 acres. In the centre was an islet from which the admiral could inspect the whole fleet. The site is traversed by the railway to the north of the village of Douai ech Chott. From this point northward the whole city was laid out in rectangular blocks, each about 13oXsoo feet and numerous streets have been located. See Haverfield, Ancient Town Planning (Oxford, 1913, 113-115).Byrsa.—The hill of St. Louis, the ancient citadel of Byrsa, has a circuit of 4,525 ft. It appears to have been surrounded, at least at certain points, by several lines of fortifications which have been found to a height of over 20 metres; a well preserved battery for catapults and munition store was also found, but de stroyed. See R. Fuchs in Jahrb. d. Instituts xxxii. (1917); Arch. Auz. 3 sqq. It was, however, dismantled by P. Scipio Africanus the younger, in 146 B.C., and was only ref ortified by Theodosius II. in A.D. 424; subsequently its walls were again renewed by Belisarius in 553. On the plateau of Byrsa have been found the most ancient of the Punic tombs, huge cisterns in the eastern part, and near the chapel of St. Louis the foundations of the famous temple of Eshmun and the palace of the Roman pro consul. To the west are the ruins of the amphitheatre. Rather more than half a mile north-west of Byrsa are the huge cisterns of La Malga, which, at the time of the Arab geographer, Idrisi, still comprised twenty-four parallel covered reservoirs of which fifteen only remain (3 r 2 X41 o feet over all) . A more recent theory identifies the site of Byrsa with that of La Goletta and the two ports, the quadrilateral commercial harbour and the circular naval harbour, with the Goletta channel and its basin and with the lagoon of Tunis itself (Pinza in Monumenti dei Lincei, xxx. [1925] 5 sqq.). The quarter of Dermeche, near the sea, whose name recalls the Latin Thermis or Thermas, is remarkable for the imposing remains of the baths (thermae) of Antoninus. Not far off is a Byzantine church with a baptistery, etc. A precinct of Tanit with a large cemetery of infants, small animals and birds, has been also discovered. Farther north are the huge reservoirs of Borj-Jedid which are sufficiently well preserved to be used for the supply of La Goletta.

Behind the small fort of Borj-Jedid is the plateau of the Odeum where the theatre and odeum, with fine marble statues of the Roman period and some private houses have been laid bare; beyond is the great Christian basilica of Damus-el-Karita (per haps a corruption of Domus Caritatis) ; in the direction of Sidi bu-Said is the platea nova, the huge stairway of which, like so many other Carthaginian buildings, has of late years been de stroyed by the Arabs for use as building material; on the coast near St. Monica is the necropolis of Rabs where fine anthropoid sarcophagi of the Punic period have been found; while to the north of Damus-el-Karita is the basilica of S. Perpetua. Several extensive cemeteries have been found at various points. In the quarter of Megara (Magaria, mod. La Marsa) it would seem that there never were more than isolated buildings, villas in the midst of gardens. At Jebel Khaui (Cape Kamart) there is a Jewish cemetery.

We must mention finally the gigantic remains in the western plain of the Roman aqueduct which carried water from Jebel Zaghwan (Mons Zeugitanus) and Juggar (Zucchara) to the cis terns of La Malga. From the nympnaeum of Zaghwan to Car thage this aqueduct is 6r Roman miles (about 56 English miles) long; in the plain of Manuba its arches are nearly 49 ft. high.

The main authority for the topography and the history of the excavations is Audollent's Carthage romaine (Paris, 19o1). A topographical and archaeological map of the site was published in 1907: but there is no general up-to-date resume. For a brief bibliography and plan see Pace and Lantier in Monumenti dei Lincei xxx. (1926), 129 sqq. (X.) The history of Carthage falls into five periods : (1) from the foundation to the beginning of the wars with the Sicilian Greeks in 550 B.C.; (2) from 55o to 265 B.C., the first year of the Punic Wars; (3) the Punic Wars to the fall of Carthage in 14o B.C.; (4) the period of Roman and Vandal rule, down to the capture of Carthage by Belisarius (A.D. 553) ; (5) the period of Byzantine rule, down to the destruction of the city by the Arabs in A.D. 698.

(1)

Foundation to 550 B.C.—From an extremely remote pe riod Phoenician sailors had visited the African coast and had had commercial relations with the Libyan tribes who inhabited the district which forms the modern Tunis. In the i6th century B.C. the Sidonians established a trading station called Cambe or Cac cabe. Near Bordj-Jedid, unmistakable traces of this early settle ment have been found. Carthage was founded about 85o B.C. by Tyrian emigrants led by Elissa or Elissar, the daughter of the Tyrian king Mutton I., fleeing from the tyranny of her brother Pygmalion. Elissa subsequently received the name of Dido, i.e., "the fugitive." The new arrivals bought from the mixed Libyo Phoenician peoples of the neighbourhood a piece of land on which to build a "new city," Karthadshat, whence the Greek and Roman forms of the name. Dido, having obtained "as much land as could be contained by the skin of an ox," proceeded to cut the skin of a slain ox into strips narrow enough to extend round the whole of the hill which afterwards from this episode gained the name of Byrsa (Gr. bursa "hide," "skin," play on words with the Phoeni cian bosra, borsa, "citadel," "fortress").In the 6th century, Carthage is a considerable capital with a domain divided into the three districts of Zeugitana, Byzacium, and the Emporia which stretch to the centre of the Great Syrtis. The limit between the settlements of Carthage and those of the Greeks of Cyrene were eventually fixed and marked by a monu ment known as the "Altar of Philemae." The destruction of Tyre by Nebuchadrezzar (q.v.) in the first half of the 6th century, enabled Carthage to take its place as mistress of the Mediterra nean. The Phoenician colonies founded by Tyre and Sidon in Sicily and Spain, threatened by the Greeks, sought help from Carthage. The Greek colonization of Sicily was checked, while Carthage established herself on all the Sicilian coast and the neighbouring islands as far as the Balearic Islands and the coast of Spain.

(2) Wars with the Greeks.—In 55o B.C. the Carthaginians led by Malchus, the suffete (see p. 946: Constitution), conquered almost all Sicily. In 536 B.C. they defeated the Phoceans and the Massaliotes on the Corsican coast. But Malchus, having failed in Sardinia, was banished by the Carthaginian senate. He laid siege to Carthage itself, and entered the city as a victor. He was put to death by the party which had supported him. Mago, son of Hanno, of the powerful Barca house succeeded Malchus. He conquered Sardinia and the Balearic Islands, where he founded Port Mahon (Portus Magonis). The first agreement between Carthage and Rome was made in 509 B.C., in the consulship of Iunius Brutus and Marcus Horatius. It assigned Italy to the Romans and the African waters to Carthage. Sicily remained a neutral zone.

Mago was succeeded by his elder son Hasdrubal (c. 50o) who died in Sardinia about 485 B.C. His brother Hamilcar, having collected a fleet of 200 galleys for the conquest of Sicily, was de feated by the combined forces of Gelon of Syracuse and Theron of Agrigentum under the walls of Himera in 48o B.C. the year in which the Persians' fleet was defeated at Salamis. It is claimed that 150,000 Carthaginians were taken prisoners.

About 46o B.C., Hanno, son of Hamilcar, passing beyond the Pillars of Hercules (Straits of Gibraltar), founded settlements along the West African coast, in the modern Senegal and Guinea, and even in Madeira and the Canary Islands.

In Sicily, the war lasted for a century. In 406

B.C. Hannibal and Himilco destroyed Agrigentum and threatened Gela, but the Carthaginians were forced back on their stronghold in the south west by Dionysius the Elder, Dionysius the Younger, Timoleon and Agathocles successively, whose cause was aided by a terrible plague and civil troubles in Carthage itself. Profiting by these troubles, Timoleon defeated the Carthaginians at Crimissus in B.C. The subsequent peace was not of long duration; Aga thocles besieged Carthage, which was then handicapped by the conspiracy of Bomilcar. Bomilcar was crucified, and Agathocles having been obliged to return to Sicily, his general Eumarcus was compelled to carry his army out of Africa, where it had main tained itself for three years (Aug. 3ro to Oct. 307 B.c.). After the death of Agathocles, the Carthaginians re-established their supremacy in Sicily, and Mago even offered assistance to Rome against the invasion of Pyrrhus (28o B.c.). Pyrrhus crossed to Sicily in 277 B.C., and was preparing to sail to Africa when he was compelled to return to Italy. Delivered from these dangers, Car thage claimed the monopoly of Mediterranean waters, and seized every foreign ship found between Sardinia and the Pillars of Her cules.(3) The Punic Wars.—(See also ROME: History). The first Punic War (268-241 B.c.) (Lat. Poeni, Phoenicians) was fought by Carthage for the defence of her Sicilian possessions and her supremacy in the Tyrrhenian Sea. The Romans, victorious at the naval battles of Mylae and Ecnomis (26o and 256 B.c.), sent M. Attilius Regulus with an army to Africa. But the Carthaginians, with the help of the Spartan Xanthippus, captured Regulus. The fighting was then transferred to Sicily, where Hasdrubal was de feated at Panormus (25o B.c.) ; subsequently the Romans failed before Lilybaeum and were defeated at Drepanum, but their vic tory at the Aegates Islands ended the war (245 B.c.) . Carthage now desired to disband her forces, but the mercenaries claimed their arrears of pay, and, on being refused, revolted under Spen dius and Matho, pillaged the suburbs of Carthage and laid siege to the city itself. The genius of Hamilcar Barca raised the siege; the mercenaries were cut down in the defile of the Axe. This war is known as the bellum inexpiabile.

Carthage then undertook the conquest of Spain. This oper ation lasted nine years up to the day of Hamilcar's death, in 228 B.C. His son-in-law, Hasdrubal Pulcher, built Carthagena in 227 B.C. and concluded with Rome a treaty by which the Ebro was adopted as the boundary of the Carthaginian sphere. On his death the soldiers chose as leader Hannibal, son of Hamilcar. At this period, Carthage, with a population of perhaps i,000,000, was in the enjoyment of extraordinary prosperity. The manufacture of woven goods was a flourishing industry. In Sicily, Italy and Greece the Carthaginians sold black slaves, ivory, metals, precious stones and all the products of Central Africa. In Spain, they exploited the modern mines of Huelva, Osca and Carthagena. The district round Carthage, with its amazing fertility, was the granary of the city, as it was later that of Rome.

In the midst of this prosperity the Second War with Rome broke out. The campaigns of Hannibal (q.v.) in Spain, Italy and Africa have won the admiration of military experts of all ages. In gig B.C. he captured Saguntum, which was in alliance with Rome. Passing through Spain and Gaul, Hannibal resolved to carry the war into the heart of Italy (218-217 B.c.). The battles of the Ticinus, Trebbia and Trasimene Lake are but stages in the wonderful progress which culminated in the battle of Cannae (q.v., Aug. 2, 216 B.c.) . The road to Rome was now open to him, but he did not profit by his advantage, while the Carthaginian senate withheld all further support. His brother Hasdrubal with his relieving army was defeated at the Metaurus in 207 B.C. ; the Romans recovered their hold in Spain, and seeing that Hannibal was unable to move in Italy, carried the war back to Africa. Hearing that Scipio (q.v.) had taken Utica (203 B.c.) and de f eated Hasdrubal and Syphax, king of Numidia, Hannibal re turned from Italy, but with a hastily levied army was defeated at Zama (Oct. Ig, 202 B.C.). The subsequent peace was disastrous to Carthage, which lost its fleet and all save its African posses sions.

After the Second War, Carthage soon revived. The population is said to have numbered 700,000, and the city never ceased to inspire alarm at Rome. The Numidian, Prince Massinissa, rival of Syphax and a Roman protégé, took advantage of a clause in the treaty of 202 B.C., which forbade Carthage to make war with out the consent of the Roman senate, to extend his possessions at the expense of Carthage. In response to a protest from Car thage an embassy including Porcius Cato the Elder (q.v.) was sent to inquire into the matter, and Cato was so impressed with the city that on returning to Rome he never made a speech with out concluding with the warning Delenda est Carthago ("Car thage must be destroyed").

At this time, the popular faction, which was turbulent and exasperated by the bad faith of the Romans, expelled the Numid ian party and declared war in 149 B.C. on Massinissa who was victorious at Oroscope. Rome then intervened. The third Punic War lasted three years, and after a heroic resistance the city fell in 246 B.C. The last champions of liberty entrenched themselves under Hasdrubal in the temple of Eshmun, the site of which is now occupied by the chapel of St. Louis. The Roman troops were let loose to plunder and burn. The site was dedicated to the infernal gods, and all human habitation throughout the ruined area was forbidden.

Constitution and Religion.

The narrative may here be in terrupted by an account of the political and religious develop ment of Phoenician Carthage. Carthage was an aristocratic republic based on wealth rather than on birth. So Aristotle, writ ing about 33o B.C., emphasizes the importance of great wealth in Carthaginian politics. The government was in fact a plutocracy. The aristocratic party was represented by the two suffetes and the senate; the democratic by the popular assembly. The suf fetes (So f etim), two in number, presided in the senate and con trolled the civil administration. The office was annual, but there was no limit to re-election. Hannibal was elected for 22 years. The senate, composed of 30o members, exercised ultimate control over all public affairs, decided on peace and war, and nominated the Commission of Ten, which was entrusted with the duty of aiding and controlling the suffetes. The commission was subse quently replaced by a council of one hundred (Gr. gerousia). This tribunal, which gradually became tyrannical, met frequently at night in the Temple of Eshmun, on Byrsa, in secret sessions.The popular assembly was composed of those who possessed a certain property-qualification (translated into Gr. as timouchoi). The election of the suffetes had to be ratified by this assembly. The two bodies were almost always in opposition. The army was recruited externally by senators who were sent to the great em poria or trade-centres, even to the most remote, to contract with local princes for men and officers. Payments were frequently in arrears; hence the terrible revolts such as that of the bellum inexpiabile. It was not till the 3rd century B.C. that Carthage, in imitation of the kings of Syria and Egypt, began to make use of elephants in war. In addition to the mercenaries, the army contained a legion composed of young men belonging to the best families in the state; this force was an important nursery of officers.

The religion of Carthage was that of the Phoenicians. Over an army of minor deities (alonim and baalim) towered the trinity of Baal-Ammon, or Moloch; Tanit, the virgin goddess of the heavens and the moon, the Phoenician Astarte ; and Eshmun, identified with Asklepios, protector of the acropolis. There were also special cults of Iolaus or Tammuz-Adonis, of Patechus or Pygmaeus, a repulsive monster like the Egyptian Ptah, whose images were placed on the prows of ships to frighten the enemy, and the Tyrian Melkhart (Hercules). The statue of this god was carried to Rome after the siege of 146 B.C.

From the close of the 4th century B.C. the intimate relations between the Carthaginians and the Sicilian Greeks began to in troduce Hellenic elements into this religion. In the forum of Carthage was a temple to Apollo containing a colossal statue, which was transported to Rome. The Carthaginians sent offerings to Delphi, and Tanit approximated to some extent to Demeter; hence on the coins we find the head of Tanit or the Punic Astarte crowned with ears of corn, in imitation of the coins of the Greek Sicilian colonies. The symbol of Tanit is the crescent moon; in her temple at Carthage was preserved a famous veil which was venerated as the city's palladium. On the votive stelae which have been unearthed, we find invocations to Tanit and Baal-Am mon (associate gods) . Baal-Ammon or Moloch is represented as an old man with ram's horns on his forehead ; the ram is fre quently found with his statues. He appears also with a scythe in his hand. At Carthage children were sacrificed to him, and in his temple there was a colossal bronze statue in the arms of which were placed the victims. The children slipped one by one from the arms into a furnace amid the plaudits of fanatical worshippers.

(4) Roman Period.—In 122 B.C., the Roman senate, on the proposal of Rubrius, decided to plant a colony on the site of Carthage. C. Gracchus and Fulvius Flaccus were entrusted with the foundation of the new city, Colonia lunonia, placed under the protection of Juno Caelestis. But its prosperity was obstruct ed both by unpropitious omens and by the very recollection of the ancient feud, and about 3o years later Marius, proscribed by Sulla, found the ruins practically deserted (see MARCUS). In the neighbourhood were the scattered remnants of the old Punic population. They sent ambassadors to Mithridates, the king of Pontus, assuring him of their support against Rome. Ultimately M. Minucius Rufus passed a law abrogating that of 122 B.C. and suppressing the Colonia lunonia.

Julius Caesar, pursuing the last supporters of Pompey, encamped on the ruins of the city. Returning to Rome, he despatched thither the poor citizens who were demanding land from him. Later Augustus sent new colonists, and, henceforward, the ma chinery of administration was regularly centred there. The pro consuls of the African province had hitherto lived at Utica. In 14 to 13 B.c., C. Sentius Saturninus transferred his headquarters to Carthage, which was henceforth known as Colonia Julia Car thago.

Pomponius Mela and Strabo already describe Carthage as among the greatest and most wealthy cities of the empire. Hero dian puts it second to Rome. Virgil, in the Aeneid, celebrated the misfortunes of Dido, whom the colonists ultimately identified with Tanit-Astarte; a public Dido-cult grew up. The religious character of these legends reawakened the old distrust, and even up to the invasions of the Vandals, Rome forbade the recon struction of the city walls. The revolt of Clodius Macer, legate of Numidia, in A.D. 68, was warmly supported by Carthage. At the moment of the accession of Vitellius, Piso, governor of the province of Africa, was in his turn proclaimed emperor at Car thage. Under Hadrian and Antoninus, there was built the famous Zaghwan aqueduct, which poured more than seven million gallons of water a day into the reservoirs of the MVIapalia (La Malga). Under Antoninus Pius, a fire devastated the quarter of the forum.

In the early history of Christianity Carthage played an auspi cious part (see CARTHAGE, SYNODS OF). The labours of Delattre have filled the St. Louis Museum at Carthage with memorials of the early Church. From the end of the 2nd century there was a bishop of Carthage ; the first was Agrippinus, the second Optatus. At the head of the apologists, whom the persecutions inspired, stands Tertullian. In A.D. 202 or 203, in the amphitheatre, where Cardinal Lavigerie erected a cross in commemoration, occurred the martyrdom of Perpetua and Felicitas. Tertullian was suc ceeded (A.D. 248) by a no less famous bishop, Cyprian. About this time the proconsul Gordian had himself proclaimed (A.D. 239) emperor at Thysdrus (El Jem). Shortly afterwards Sabin ianus, aspiring to the same dignity, was besieged by the procurator of Mauretania ; the inhabitants gave him up and thus obtained a disgraceful pardon. Peace being restored, the persecution of the Christians was renewed by an edict of Decius (A.D. 250). Cyprian escaped, and subsequently caused the heresy of Novatian to be condemned in the council of A.D. 251. In A.D. 257, in a new perse cution under Valerian, Cyprian was beheaded by the proconsul Galerius Maximus.

About A.D. 264 or 265 a certain Celsus proclaimed himself emperor at Carthage, but was quickly slain. Probus, like Hadrian and Severus, visited the city, and Maximian had new baths con structed. Under Constantius Chlorus, Maxentius proclaimed him self emperor in Africa, but the garrison of Carthage, which was hostile to the pretender, compelled L. Domitius Alexander to as sume the purple. Domitius was however captured by Maxentius and strangled. About A.D 311 there arose the Donatist heresy, supported by 270 African bishops. At the synod of Carthage in A.D. 411 this heresy was condemned owing to the eloquence of Augustine. Two years later the Carthaginian sectaries even ven tured upon a political rebellion under the leadership of Hera clianus, who proclaimed himself emperor and actually dared to make a descent on Italy itself, leaving his son-in-law Sabinus in command at Carthage. Being defeated he fled to Carthage where he was put to death (A.D. 413). Donatism was followed by Pelagianism also of Carthaginian origin, and these religious troubles were not settled when in May A.D. 429 the Vandals, on the appeal of Count Boniface, governor of Africa, crossed the Straits of Gibraltar and invaded Mauretania. Gaiseric appeared in A.D. 439 before the walls of Carthage, which had been hastily rebuilt by the order of Theodosius. Gaiseric entered almost with out a blow and gave over the city to plunder before departing for his attack on Italy. From this time Carthage became, in the hands of the Vandals, a mere pirate stronghold. Once, in A.D. 470, the fleet of the Eastern empire under the orders of Basiliscus appeared in the Bay of Carthage, but Gaiseric succeeded in set ting fire to the attacking ships and from Byrsa watched their en tire annihilation.

(5) Byzantine Rule.—Under Gaiseric's successors Carthage was still the scene of many displays of savage brutality, though Thrasamund built new baths and a basilica. Gelimer, the last Vandal king, was defeated at Decimum by the Byzantine army under Belisarius, who entered Carthage unopposed (A.D. 553). The restored city now received the name of Colonia lustiniana Carthago; Belisarius rebuilt the walls and entrusted the govern ment to Solomon.

At length the Arabs, having conquered Cyrenaica and Tripoli tana (A.D. 647), and founded Kairawan (A.D. 670), arrived before Carthage. In A.D. 697 Hasan ibn en-Noman, the Gassanid gover nor of Egypt, captured the city almost without resistance. But the patrician Ioannes retook the city and put it in a state of de fence. Hasan returned, defeated the Byzantines again, and de creed the entire destruction of the city. In A.D. 698 Carthage finally disappears from history. Once again only does the name appear, in the middle ages, when the French king Louis IX., at the head of the 8th crusade, disembarked there on July 17, 12 70. Recherches sur l'emplacement de Carthage (1833) ; D. de la Malle, Topographie de Carthage (1835) ; Nathan Davis, Carthage and her remains (1861) ; Beule, Fouilles d Carthage (1861) ; Victor Guerin, voyage archeologique dans le regence de Tunis (1862) ; E. de Sainte Marie, Mission et Carthage (1884) ; C. Tissot, Geographie com paree de la province romaine d'Afrique (1884-88) 2 vol. ; E. Babelon, Carthage (1896) ; Otto Meltzer, Geschichte der Karthager (1879-96) • Paul Monceaux, Les Africans, etude sur la litterature latine de l'Afrique; Les patens (1898) ; Histoire litteraire de l'Afrique chretienne (19oI–o9) ; Rallu de Lessert, Vicaires et comtes d'Afrique (1892) ; Fastes des provinces africaines sous la domination romaine (1896-1901) ; R. Cagnat, L'Armee romaine d'Afrique (1892) ; Ch. Diehl, L'afrique byzantine, histoire de la domination byzantine en A f rique (1896) ; Aug. Audollent, Carthage romaine (i 90 i) ; A. J. Church and A. Gilman, Carthage in "Story of the Nations" series (1886). For the numerous publications of Pere Delattre, scattered in various periodicals, see d'Anselme de Puisaye, Etudes sur les diverses publications du R. P. Delattre (1895) ; Mabel Moore, Carthage of the Phoenicians (1905) ; Stephane Gsell, Histoire ancienne de l'Afrique du Nord, vol. IV., la Civilisation carthaginoise (1920) ; Dr. Carton, Pour Visiter Carthage (Tunis, 5924).

Among ancient authorities are:— (a) Polybius, Diodorus, Siculus, Livy, Appian, Justin, Strabo; (b) for the Christian period: Tertullian, Cyprian, Augustine; (c) for the Byzantine and Vandal periods, Pro copius and Victor de Vita. (J. BA.)