Cho Cho Cho Cho

CHO CHO CHO CHO Synthetic Glucosides and the Structure of Glucose.— Aldehydes ordinarily react with one or with two molecules of ethyl alcohol to give either an alcoholate, or an acetal, • Methyl alcohol in the presence of an acid as catalyst yields, a dimethyl-acetal, A sugar aldose, however, under similar conditions reacts with one molecule of methyl alcohol, with elimination of one molecule of water: C6H1206-1-CH3•OH--. The resulting compound, a methyl-aldoside, can only be repre sented, on the basis of rules of valency, as a cyclic compound (V. and VI., below) . It is isolated in two different forms which are interconvertible. Thus, by the agency of methyl alcohol con taining o.5% hydrogen chloride, glucose is converted on heating into, (I) a-methyl-glucoside having m.p. i66° and a specific rotation of +159°, and (2) 0-methyl-glucoside having m.p. 1o5° and a rotation of —34°. These differ remarkably in their be haviour towards enzymes. The enzyme maltase is specific for a methyl glucoside, converting it into glucose and methyl alcohol.

The enzymes of emulsin, on the other hand, convert the 0-glu coside into glucose and methyl alcohol. Heating with aqueous mineral acid regenerates glucose from each glucoside.

A striking fact, related to these observations, is that dextro rotatory glucose can also be isolated in two crystalline forms which are interconvertible, and so also can its penta-acetate, its penta-benzoate, as well as other derivatives. By crystallizing glucose from alcohol or from acetic acid the a form is obtained, m.p. 146°, having a specific rotation From solution in pyridine the crystalline 0-form is isolated, m.p. 148°, [a]D+ 17°. Each of these forms changes in aqueous solution to an equilibrium mixture having this change being known as "mutarotation." These two forms are structurally related to the a- and 0-methyl glucosides, and since the cyclic formulae In formulae (I.) and (II.) it is seen that the potential aldehyde group now becomes asymmetric and the arrangement of the H and OH in space in two possible ways at carbon atom No. i accounts for the existence of the two stereochemical forms, a and 0-, having different specific rotations. It has been shown that the glucoside (V.) is hydrolysed to the glucose form (I.) and the glucoside (VI.) to (II.) by the action of enzymes. The analo gous optical properties also support these inter-relations of sugar and glucoside. Moreover, the presence of the two OH groups on the right of the contiguous carbon atoms (i) and (2) in a- glucose (I.) is demonstrated by the ease with which this form, as distinct from the 0-form, combines with boric acid.

The general form of the structure here assigned to glucose and its glucosides applies equally to all the simple sugars, both of the pentose and hexose class; so that the generalization is reached that the ordinary varieties of these sugars exist as six atom rings. To preserve the relationship between aldehyde and ring-forms the structures are usually written as (I.) and (II.) above, but actually a model constructed on these lines would more accurately represent the sugars as hexagonal figures. Indeed, the sugars may be clearly pictured if we consider that they are derivatives of a parent substance, y-pyran (A), which, if suitably hydroxylated and reduced would give the sugar form (B) which has been named pyranose, wherein the group marked the expressions (IV.) and (V.) for a-and j3-forms; but (VI.) is the most reasonable mode of formulating (V.) as fructo-pyranose.

pentose. The corresponding formula for a hexose is (C), which contains as a side chain a — CH2OH group.

The spatial distribution of the H and OH atoms or groups accounts for the existence of arabinose, xylose, ribose, and lyxose. These sugars may thus be named arabo-pyranose, xylo pyranose, etc., the spatial relationships being clearly seen if we show the 6-atom ring in perspective, with the H and OH at each of the five C atoms either directed above this plane of the ring or below it.

The configurations for lyxose and ribose may be similarly sketched by referring to the provisional formulae for the pentoses given earlier. These would be designated lyxo-pyranose and ribo-pyranose on this nomenclature, which combines both structural and spatial considerations.

In the same way, formula (C) represents the common forms of glucose, of mannose and of galactose, which may be correctly described as gluco-pyranose, galacto-pyranose, etc. But the spa tial relationships of H and OH at the carbon atoms of the ring are not shown in (C).

Fructose.

Fructose, laevulose or fruit sugar, is the commonest of the ketoses. It is formed along with glucose by inversion of cane sugar (sucrose) and occurs mixed with glucose in fruit juices. It is best prepared by digesting the polysac charide, inulin (q.v.) with dilute oxalic acid. Crystalline fructose, m.p. 95°, is strongly laevorotatory in solution, having —134°, which changes by mutarotation to Although laevorotatory its configuration is closely related to d-glucose, and hence it is named d-fructose. This fact is established in that by nascent hydrogen fructose passes into d-sorbitol, as does glucose. Fructose gives the same phenylosazone as glucose. It combines additively with hydrogen cyanide, and hydrolysis of this product, followed by reduction of the OH groups by by driodic acid, gives methylbutylacetic acid (II.). Hence the pro visional formula for fructose represents the sugar as a ketone (I.) Fructose, like glucose, is fermentable by yeast. It probably plays a different part in metabolism from glucose, and seems to be more intimately connected with tissue formation, whilst glucose is more concerned with respiration.

The Labile or 7-Sugars (Furanoses).

Whilst fructose on isolation is found to have the above 6-atom ring, yet there is strong evidence that when fructose occurs in combination in cane sugar and in inulin the structure is different and has a five atom ring. The first sugar derivative of this type to be recog nized (Emil Fischer) was 7-methyl-glucoside, which is obtained by condensing glucose and methyl alcohol containing I% HC1 in the cold. It is now known that most simple sugars can assume the 'y- or labile form under analogous conditions. Derivatives of these have been prepared, and they are shown to be related, not to pyran as the parent substance, but to furan, and are therefore named furanoses.The above constitutional problems have been elucidated by studying sugar derivatives such as methylated, acetylated, and benzoylated sugars, and also the acetone-sugars. A summary of the development of the experimental proofs has appeared in the Annual Reports of the Chemical Society (Organic Chemistry, Aliphatic Division) for the years 1923-1927; see also W. N. Haworth, The Constitution of Sugars (London, 1928).

Synthesis of Sugar.

By combining certain reactions which have been already considered it is possible to pass from any monosaccharide to the one containing an additional carbon atom. Thus addition of HCN to glucose (A) (Kiliani) gives two The mutarotation of fructose shows that an a-form of the sugar exists, and again, as with glucose, the ketone formula (III.) must give place to the cyclic, 6-atom ring structure indicated in nitriles (B and C), hydrolysable to the acids, the lactones of which may be reduced by Fischer's method to the corresponding heptoses. The opposite effect, or degradation, can be accom plished by several methods. In one of these the calcium salt of gluconic acid is oxidized with hydrogen peroxide in the pres ence of ferric acetate, when the following reaction takes place: glucose yields d-arabinose.The action of pyridine or quinoline on the lactones of gluconic acid results in the inversion of the groups attached to the second carbon atom (epimerization). Mannonolactone is thus produced which may be reduced to mannose. The reaction is general and has been used frequently in the synthesis of rare sugars.

An aldose may be converted into a ketose through the osazone, the reactions being clear from the following scheme: The reverse (e.g., glucose) transformation may be effected in the following way: The elucidation of these and similar reactions prepared the way for the complete synthesis of the natural sugars from their elements. Glyceraldehyde, gives with dilute alkali dihydroxyacetone, the crude mixture of the two being termed glycerose. These two molecules then unite by an aldol condensation to give a-acrose, which was identified as dl-fructose by means of its osazone.

The osazone yielded the osone which was then reduced to the pure dl-fructose (see above). The operations were next con tinued according to the scheme : a-acrose--*a-acritol (mainly d1-mannitol)->dl-mannose-- dl-mannonic acid-*d-mannonic acid d-mannose- > d-glucosazone--> d-glucosone- > d-fructose. Also d-mannonic acid-->d-gluconic acid-->d-glucose. The /-series of sugars may be obtained similarly from l-mannonic acid.

The photosynthesis of carbohydrates in the plant from car bon dioxide requires the presence of chlorophyll (q.v.). Very recently it has been claimed that on suitable coloured surfaces carbon dioxide and water can be induced to yield true carbo hydrate material under the influence of light. The reaction requires intense energy supplies.

Disaccharides.

The disaccharides, C12H22011, are formed by the combination of two monosaccharide molecules with loss of one molecule of water: The reaction always involves one of the reducing groups and may involve both. The disaccharides may therefore be regarded as analogues of the methylglucosides in which the methyl radical is replaced by a sugar residue. As glucosides, they are readily hydrolysed to the component sugars by dilute acids and show the characteristic specific reactions towards enzymes. For example, maltose, an ex-glucosidic disaccharide, is readily hydrolysed in aqueous solution by maltase, whilst cellobiose, a /3-glucosidic disaccharide, is attacked by emulsin and not by maltase. Ac cording as one or both reducing groups are involved in the disaccharide linkage there exist reducing and non-reducing di saccharides, the former reducing Fehling's solution and behaving like an ordinary aldose or ketose. Typical examples are lactose (reducing) and cane sugar (non-reducing) In general the chemistry of the disaccharides resembles that of the monosaccharides, with the exception that the scope of the reactions which can be utilized is limited by the presence of the easily severed glucosidic linkage by which the two halves of the molecule are joined. The —OH groups may be substituted by acetyl groups (e.g., octa-acetyl sucrose) or by methoxy-groups (octamethyl-sucrose, etc.) or by other groups. Hydrazones, oximes and osazones are formed by the reducing disaccharides and oxidation at the reducing group gives rise to the bionic acids, which correspond with a hexonic acid such as gluconic acid.Disaccharide formation is not limited to the union of two simi lar molecules: compounds of glucose and galactose, glucose and fructose, etc., also occur, and these may exist either in a- or /3 forms. For these reasons the elucidation of the structure of the disaccharides has been a most complex problem. The methylated sugars have furnished a valuable means to this end.

Lactose.

Lactose or milk sugar may be obtained by evapora tion of whey from milk. It is not encountered in the vegetable kingdom. It reduces Fehling's solution, gives a characteristic osazone, exists in a- and /3-modifications, shows mutarotation, and forms methyl lactosides. a-Lactose has m.p. 223°. Oxidation with bromine water gives lactobionic acid which can be hydrolysed to a mixture of gluconic acid and galactose. Lac tose therefore contains one glucose and one galactose residue and these two hexoses can be obtained from lactose by hydrolysis. The free reducing group in lactose is situated in the glucose por tion. Lactose is thus a glucose j3-galactoside, having the struc tural formula (IX.), wherein A = glucose, and B =galactose.Similar experiments have been carried out with all the common reducing disaccharides and it is found that they may be accom modated by one or other of the two general formulae (IX. and X.), where A =glucose, B = either glucose or galactose according to the disaccharide selected; and the junction * may be either a- or /3- as required by a particular example.

Other Disaccharide Compounds.

Maltose is formed by the action of the enzyme diastase on starch during the generation of cereals (preparation of malt). It is prepared by the hydrolysis [of starch by diastase and forms crystals resembling glucose, 7° (equil. value), mutarotating upwards. Hydrolysis by acids or by the enzyme maltase gives two molecules of glucose. The structure of maltose is similar to that of lactose (formula IX., A and B = glucose) except that the sugar is a glucose a-glucoside (*= a-) .Cellobiose (m.p. 225° /3-form; equil. value +35°) is obtainable in the form of its octa-acetyl derivative from cotton cellulose by treatment with acetic anhydride and sulphuric acid under special conditions. Its special interest lies in the appar ently close relationship between it and cellulose. Structurally it resembles maltose except in the nature of the glucosidic linkage which is f3-. It is glucose f3-glucoside (formula IX.). Gentiobiose (m.p. 19o-195° [alp- 11°, equil. value +9.6°) is a reducing di saccharide obtained by partial hydrolysis of the trisaccharide gentianose. It is the sugar present in the glucoside amygdalin (q.v.). It differs structurally from maltose and corresponds with formula (X.). Melibiose (m.p. 88-95°, 124°, equil. value 143°) is one of the hydrolytic products of the trisaccharide raffi nose. It contains glucose and galactose residues, corresponds structurally with gentiobiose (formula X.) but is glucose a-ga lactoside.

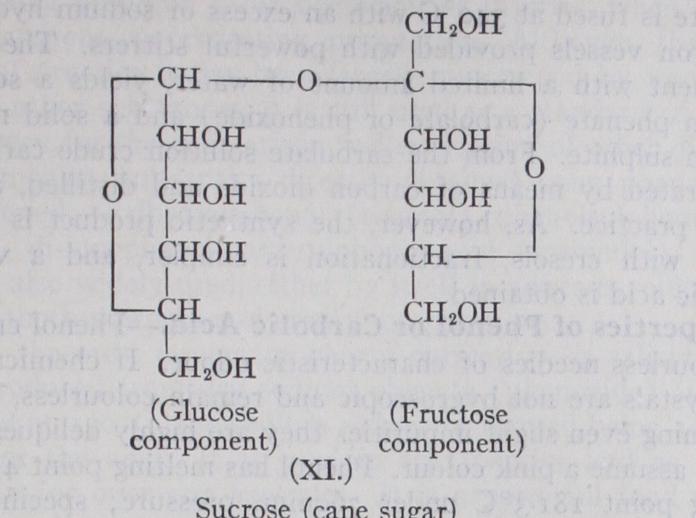

Sucrose or cane sugar (m.p. 16o°, [4+66.5°) is the most im portant non-reducing disaccharide. For description of its physi cal properties and the mode of extraction from the sugar cane and the sugar beet, see SUGAR. It is very readily hydrolysed by dilute acids to a mixture of equal quantities of glucose and fructose (termed invert sugar), but sucrose itself does not reduce Fehling's solution. In this case both reducing groups are involved in the disaccharide linkage. It gives octa-acetyl, octa-methyl derivatives, etc., and from a study of the latter the structure of sucrose has been determined (formula XI.) ; it involves a pyranose structure in the glucose portion and a furanose structure in the fructose half of the molecule.

In addition to the disaccharides similar compounds are known in which three sugar molecules are linked together (trisac charides). The best known of these are raffinose (from cotton seed meal), melezitose (from the manna exuded from the Douglas Fir) and gentianose (from gentian roots).

Polysaccharides.

The empirical formula of the members of this series is C6H10O5, or in some cases Their molecular weight is, however, very high; they are mostly amorphous, col loidal complexes, which break down on hydrolysis to monosac charides containing 5 or 6 carbon atoms. Several of the individ ual substances are of great industrial importance and are funda mental in the synthetic processes taking place in the living cell. Their colloidal nature and high molecular weight greatly in crease the difficulties inherent in their chemical investigation, and the structural formula of no one of them can at present be regarded as definitely established.

Cellulose.

The name cellulose has been given to several prod ucts found in the vegetable kingdom. These consist for the most part of complexes of various extraneous materials with normal cellulose, the purest form of the latter being found in cotton. The same cellulose is present also to a greater or less extent in flax, hemp, wood, straw, etc. For the part played by cellulose in paper making, see PAPER.Cotton cellulose is a white fibrous substance, which contains when air-dried some 7% of moisture. It is insoluble in all the usual solvents, but dissolves readily in an ammoniacal solution of copper hydroxide (Schweitzer's reagent) and in the concen trated solutions of certain metallic salts. On dilution it is again precipitated. It is unaffected by moist chlorine, and as this reagent converts into soluble substances almost all the materials which accompany cellulose this provides a convenient method for its purification and estimation. Treatment of unglazed paper with strong sulphuric acid converts the superficial layer into the so-called "amyloid" modification, with production of parchment paper. Another, somewhat similar transformation is the con version of cellulose (cotton) into mercerized cotton by the action of cold 15-25% sodium hydroxide solution. Various indefinite substances known as hydrocelluloses and oxycelluloses are pro duced respectively by the action of acids and of oxidizing agents.

The most important compounds of cellulose are the esters. These include the nitrates which are used in the manufacture of explosives (q.v.), celluloid, photographic films, etc. The xan thate, formed by the action of caustic soda and carbon disul phide (R•OH+CS2+NaOH is of prime importance in the viscose industry, in which a suitably pre pared cellulose xanthate solution is forced through fine orifices into an acid bath, with the regeneration of cellulose in the form of silky filaments (see SILK, ARTIFICIAL).

The acetates of cellulose, produced by the action of acetic anhydride in the presence of a catalyst, are of equal importance in that in one or other of their forms they are the basis of cellulose acetate silk, of non-inflammable films, and of many varnishes and lacquers; they can be used as insulating materials in elec trical work.

Much attention is,being given to the problem of the internal structure of cellulose. It can be converted into glucose quanti tatively by hydrolysis and so consists solely of glucose residues. The first and fourth carbon atoms of the C6 unit are concerned in the mutual union of these glucose residues, which are all identical in structure in cellulose (for mula I.). The acetolysis of cotton cel lulose to give cellobiose (see above) strengthens this view.

On the basis of X-ray measurements cellulose can be regarded as a closely packed array of continuous chains of gluco-pyranose residues, arranged as formula (I.) and having the same mode of linking as the related disacchaside cellobiose.

Starch.

This polysaccharide is present in assimilating plants and occurs in large amounts in cereals, grains, roots, tubers, etc. It occurs in the form of gronules built up of concen tric layers round a nucleus. When heated with water the outer integument of the granule bursts and an opalescent liquid is formed which sets to a paste when cold. The granules and the paste give a characteristic deep blue colour with iodine. It has been claimed that starch can be separated into two portions termed amylose and amylopectin, which differ in their colour reactions with iodine (the latter giving a violet coloration and the former blue) and in their capacity to give a starch paste.The action of diastase on starch yields the disaccharide mal tose. Complete hydrolysis yields glucose quantitatively. The controlled action of acids or ferments has led to the preparation of a large number of substances intermediate between starch and maltose. These are classed generally as dextrins. They differ considerably from one another in physical properties and their relationship to starch on the one hand and to the simple mono saccharides on the other has yet to be worked out. Little can be said at present regarding the structural relationship of starch and cellulose, but that maltose is closely connected with the structure of starch seems to be clear (see also FERMEN TATION) .

Glycogen or animal starch, occurs in the animal muscle and in the liver of mammalia. It gives a red coloration with iodine and is readily hydrolysed to give glucose in quantita tive yield. It is more labile than ordinary starch which it re sembles in many particulars. Like starch and cellulose, its methylated derivative yields 2:3:6-trimethylglucose on hydroly sis. Lichenin or moss starch, is yet another example of a built up solely of glucose units. It occurs in Iceland moss. Chemically it has many properties in common with cellulose.

Inulin, (C6H1005)n, is of common occurrence in plants as a reserve food-stuff, where it may often take the place of starch. It is composed entirely of fructose units and hydrolysis of inulin by oxalic acid provides the best method for obtaining ordinary crys talline fructose. Despite this fact the fructose unit in inulin is not the pyranose type of fructose, but is the furanose or labile type of the sugar. Iodine gives a yellow colour with inulin. The two groups concerned in the union of the fructose units in the complex are the primary alcoholic group at the first carbon atom and the reducing group at tached to the second carbon of the ketose. The number of such units has not yet been ascertained. See special articles on various carbohydrates.

BIBLIOGRAPHY.-For summaries of the most recent developments Bibliography.-For summaries of the most recent developments see the Annual Reports on the Progress of Chemistry for recent years (Chemical Society, London) • W. N. Haworth, The Constitution of Sugar (London, 1928) ; E. F. Armstrong, The Simple Carbohydrates and the Glucosides, contains bibliography and summarizes the chem istry of the sugars (excluding polysaccharides) to 1924; M. Cramer, Les Sucres et leers Derives, includes the polysaccharides (complete to 1926) ; H. Pringsheim, Die Polysaccharide (1923), and Zuckerchemie, excluding the polysaccharides (complete to 1924) ; P. Karrer, Poly mere Kohlenhydrate, the polysaccharides considered more particularly as colloids (1925) ; W. M. Bayliss, The Nature of Enzyme Action; E. Heuser, Lehrbuch der Cellulosechemie (English trans., 1925). For references the following are invaluable: B. Tollens, Kurzes Handbuch der Kohlenhydrate (Leipzig, 1914) ; Emil Fischer, Untersuchungen fiber Kohlenhydrate and Fermente, I. u. II.; Lippmann, Chemie der Zucker arten (Braunschweig, i904)• (W. N. H.)