Export of Capital

CAPITAL, EXPORT OF. This expression denotes invest ment of capital abroad by a country or its inhabitants. The term may be applied either broadly to the gross amount of capital so invested during a given period, or more narrowly to the net amount, represented by an excess of capital invested externally over capital concurrently invested in the country from outside.

Export of capital presupposes the existence of a supply of capital available for investment abroad, of an effective demand and of arrangements for bringing the supply and the demand into relation with one another.

The supply of capital available to a country for investment abroad in any period forms an indefinite part of its total supply of capital available for investment at home or abroad in that period. This total includes capital which is the fruit of current savings, as well as some capital, accumulated in earlier periods, which becomes re-available for investment as a result, e.g., of liquidation of stocks in which it had been temporarily invested. In the long run current savings are all important, and the supply of capital available for investment abroad forms part of the sav ings of the country. Not all the capital which is accumulated is equally available for investment at home or abroad. Many in vestors undoubtedly prefer to invest their money at home in undertakings with which they are familiar, even if the rate of interest obtainable is relatively low; or if they control trust funds they may be restricted as regards the choice of investments. In this connection it may be noted that under English law prior to 190o trustees could only invest in certain British securities, but the Colonial Stock Act of that year extended the classes of securities open to them to include certain Colonial Government Stocks.

Competition of Home and Foreign Investments.—Home investment generally tends to exert the first pull upon the available supplies of capital, but reluctance to invest abroad may be largely overcome (where good opportunities for investment exist) by widely increased knowledge of foreign investments. As the habit of foreign investment increases, the special financial in ducement (in the form of high rates of interest) which is neces sary to overcome the distaste for foreign investments tends to diminish, and capital flows more freely over the world in response to demand. But where there is a strong internal demand for capital, as in a country which is developing rapidly, capitalists will have no strong motive to acquire experience of foreign in vestments, and the great bulk of their capital will be invested at home. For this reason the export of capital in large volume normally implies that the capital exporting country has reached a certain stage of economic maturity, at which not only is the rate of saving high, but the internal demand for capital is no longer so insistent as to offer a pre-emptive rate of return to the investor. In fact it may be possible to distinguish three succes sive stages of development :—(I ) the stage in which the rate of accumulation does not suffice to meet the home demand for capital, and there is a tendency to import capital; (2) the stage in which the rate of accumulation exceeds the home demand, and the ownership of the physical capital invested in the country by foreigners is purchased from them ; and (3) the stage at which capital is exported for investment abroad. These stages no doubt in practice overlap, but they are definitely traceable, and they are prominently exemplified by the history of the United States in recent decades (see p. 799) Demand for capital expresses itself effectively by the offer to lenders of what appears to them an adequate prospect of an attractive return on their capital. It may happen that a particu lar form of capital expenditure (e.g., on working class houses or public education) would he advantageous and highly remunera tive from the point of view of the community as a whole, and yet does not offer the prospect of a financial return to the indi vidual capitalist. In that case the demand for capital is not effective unless the expenditure is undertaken by some public body, capable if necessary of borrowing the money from the in dividual capitalist. When it is said that the distribution of newly accumulated capital between home investment and foreign invest ment is affected by the relative strength of the home and the foreign demand, this important qualification should be borne in mind. The demand for capital for investment abroad arises mainly in connection with the opening up and economic develop ment of the country in which the capital is to be invested, al though borrowing in connection with war expenditure (especially during the World War) or for the purpose of meeting budget deficits in peace time has been important on many occasions. Investment for purposes of development has the advantage of being reproductive, that is to say it enables further wealth to be created out of which the capitalist may hope to draw his interest. The economic development of new and backward countries may be enormously accelerated by the investment of capital from abroad, though abuses may arise where the interests of the country or its inhabitants are subordinated to the interests of foreign capitalists. The capital is used largely for the construction of means of communication, such as railways ; for public utility undertakings, such as gas, water and electric supply; for banks and land mortgage companies; and for mining or agricultural work, including such enterprises as tea and rubber plantations or sheep farms. It is on the whole exceptional for the imported capital to be invested in manufacturing industries, largely no doubt because the development of these industries represents a late stage in normal economic growth, a stage reached by the capital exporting countries, and partly perhaps also from a dis inclination on the part of capitalists in capital exporting countries to promote competition with the industries in their own countries. Nevertheless, there has been some tendency in recent years for large industrial undertakings in capital exporting countries to establish branch factories abroad, especially in countries to which direct shipment of goods. is uneconomic on account of a protec tive tariff or other circumstances.

Organization of Foreign Investment.

Regarding the ar rangements for bringing the supply of capital available for invest ment abroad into relation with the demand, it may be said that an elaborate organization is required and tends to grow up where capital is exported on a large scale. The market is concentrated largely in the hands of a group of financial houses, banks and merchant firms, with the Stock Exchange as an essential adjunct. In the relatively simple case where a foreign government seeks a loan, the financial house or bank with whom negotiations are conducted has to make the necessary arrangements for getting the loan underwritten (so as to ensure that the money is forthcoming even if the public do not subscribe all that is required) and for issuing the loan to individual investors. In many cases, however, financial houses have to seek out opportunities for investment abroad, to obtain "concessions," and to "nurse" projects until they are ready to be launched upon the market in the form of a public issue by a company formed to carry on the undertaking. Again, securities already issued in a foreign country may be purchased and distributed to investors in the capital exporting country by a publicly advertised offer for sale, by introduction and sale on the Stock Exchange or by placing through other channels.Relation of Foreign Investment to Foreign Trade.—It may be asked what is the relation of the export of capital to the foreign trade of the capital exporting country and of the capital importing country. When a country begins to export capital it fur nishes to foreign countries commercially a greater value of goods or services than it obtains in current exchange, the difference rep resenting the amount of capital lent. Not that the difference in value between the outward and the inward flow of goods and services is necessarily caused by the capital transaction. It may be rather that the capital transaction is caused by the existence of the difference in value between the outward and the inward flow of goods and services. From a secular point of view the latter is probably the truer explanation. The British export of capital during the 19th century was rather a consequence than a cause of the development of a number of great industries look ing to the export markets for the disposal of their products; and the development of the American export of capital in the 20th century is similarly rather a consequence than a cause of ex panded exports and restricted imports. On the other hand, the export of capital is a condition of the outward flow of goods and services exceeding the inward flow. Moreover, at any particular time the conclusion of foreign loans may be an important factor in stimulating the outward flow of goods and services from the capital exporting country or in reducing the inward flow.

In some cases it is possible to trace a close connection between a particular investment of capital abroad and a particular out flow of goods or services. Thus it can be shown that export of British capital for investment in railways in Argentina is fre quently related to the export of British railway material to Argentina, and it may be reasonable to regard the export of this material as attributable to the investment of the capital. It is, however, comparatively seldom that a connection can be traced between a particular export of goods and a particular invest ment of capital. Even in the case of an Argentine railway which purchases its equipment in Great Britain, part of the money in vested must be remitted to Argentina to pay wages of the work people engaged in building the line and to meet other local expenditure. Where no condition is attached to a loan requiring a portion of the proceeds to be expended in the lending country (as is frequently the practice in France and other Continental countries), the whole may possibly be remitted abroad by the purchase of "exchange," no part being spent directly on buying goods in the lending country.

In saying that the export of capital is related to an excess in the value of goods and services furnished by the capital export ing country over the goods and services received, it was assumed for the sake of simplicity that the country was just beginning to export capital so that the question of interest payments upon capital already invested abroad did not arise. The position, how ever, is not essentially different in the case of an old capital ex porting country. If the interest be regarded as payment for a service concurrently rendered by the capital exporting country— the service of allowing capital to be used—the statement still holds that the amount of capital exported in any year is equiva lent to the excess in value of goods and services furnished com mercially by the capital exporting country over those received commercially. The export of capital during any year may or may not exceed the value of current interest payments on capital previously invested abroad, and, in so far as it is balanced by in terest payments, the export of capital is sometimes regarded as a re-investment of the interest. This does not of course mean that the money intended for interest payments is retained abroad and directly re-invested. Nor does it mean strictly that the same money that is paid as interest is used in subscribing to new issues of capital for investment abroad. The phrase, however, implies the existence of a special, though somewhat indefinite connec tion between the two items in the international trading account. It is no doubt true to a certain extent that the capital exported in any year is derived from the income obtained from earlier in vestments abroad, and to that extent anything which affects the flow of income affects also the accumulation and outflow of capital. Further, nothing is more calculated to stimulate the export of capital than a high yield on capital already invested abroad, or to discourage it than a low yield.

Economic Effects of Capital Exports.—There is a certain presumption that an unrestricted flow of capital tends to maxi mize wealth. The export of capital from countries where it was relatively plentiful to countries where it was relatively scarce, in response to the prospect of a higher yield, has on the whole enor mously added to the wealth of the world. The rate of develop ment of new countries such as the United States has been very greatly accelerated by the investment of capital from European countries, and the annual interest represents but a small part of the wealth which was produced with the aid of the capital. Further, the prosperity of the capital exporting countries them selves was increased not merely by the relatively high rates of interest on capital invested abroad, but far more by the fact that the development of production and of transport led to a vast expansion of international trade. As already stated, the export of capital in large volume normally implies that the capital ex porting country has reached a certain stage of economic maturity at which the demand for capital for internal use is less strong than formerly. This means as a rule that a tendency to diminish ing returns is making itself felt particularly in the agricultural industries. In so far as plentiful supplies of food and raw ma terials can be purchased cheaply from abroad, the effects of the tendency to diminishing returns can be postponed. The country can support an increasing population by concentrating its activi ties in those directions in which there is a tendency to increasing or constant returns, i.e., particularly in manufacturing industries, and by obtaining from abroad those foodstuffs and raw materials which it could only produce itself at increasing cost, if at all. From this point of view the economic advantages of the export of capital to a country such as Great Britain must be regarded as immense. Had it not been for the development of agricultural industries abroad with the assistance of British and other capital, there would have been no question of Great Britain being able to support anything like the population which it supports to-day. It is no doubt true that as new countries become developed they may no longer be content to be suppliers of food and raw ma terial and may establish manufacturing industries of their own. Their internal requirements of food and raw materials may in crease to such an extent that they have less to spare for export, and this is more likely to be the case as they become more thickly populated and as a tendency to diminishing return makes itself felt. But there are still many undeveloped parts of the world, and it is in those parts that the capital exporting countries in creasingly seek opportunities for investment as the older fields become less attractive.

British Investments Abroad.—British investments abroad were built up by an almost unintermittent export of capital be tween the end of the Napoleonic wars and the outbreak of the World War. Sir George Paish estimated that at the end of 1913 the amount of capital publicly invested by British citizens in the colonies and foreign countries amounted to over £3,700,000,000, to which should be added a large amount invested privately, bringing the total to about 14,000,000,000. Of the amount pub licly invested, Sir George Paish found that some £1,780,000,000 was invested in British Dominions and possessions, some .1754, 000,000 in the United States, and some £764,000,000 in other foreign countries on the American continent. A comparatively small amount (less than £200,000,000) was invested in European countries—mainly Russia, Spain and Turkey. Sir George Paish estimated that no less than 11,521,000,000 was invested in rail ways; 1959,000,000 in Government securities; /273,000,000 in mines; 1244,000,000 in land, investment and finance companies; L147,000,000 in municipal loans; and L145,000,000 in commercial and industrial securities.

Other European Countries.—Several other European coun tries emerged as exporters of capital during the 19th century. Apart from Holland, which had established her position earlier as an investing country, these included France, Germany, Belgium and Switzerland. The amount of French capital invested externally was estimated in 1912 at some fr. 40,000,000,000 to fr. 42,000, 000,000. French investors tended to concentrate their invest ments in Europe, Egypt and the French African colonies; and showed a marked preference for Government bonds, including Russian Government issues which were held very extensively. They also held considerable investments in South America, Mexico and the Transvaal.

The amount of German investments was variously estimated at £1,000,000,000 to L1,250,000,000 before the World War. A large part was represented by Russian bonds, railway and indus trial securities; and German investors had large interests in Austria-Hungary, Italy, Rumania and the Balkans. They also had substantial interests farther afield, in the United States and Canada, South America and the Far East.

The position then before the World War was that Great Britain, and to a smaller extent France, Germany and some other European countries, had built up substantial external investments, and were in the habit of adding to them year by year through the export of capital. Apart from these, no other countries exported capital on balance, though some capital importing countries also invested capital abroad.

United States.—Among these countries was the United States, which, during the two decades before the war, had invested con siderable sums in the development of industries in Canada, in Mexico and Cuba; and had also repurchased from Europe con siderable amounts of American railway securities. The flow of capital, however, continued, on balance, to be into the United States. At the outbreak of the war in 1914 European holdings of American securities were probably between $4,500,000,000 and $5,000,000,000. American external investments probably did not exceed one-third of this amount.

Changes Due to the War.—The World War brought enor mous changes in the sphere of international indebtedness, the ex tent of which cannot even now be precisely gauged. The initial shock to the credit system at the outbreak of war caused an imme diate stoppage in the normal flow of capital from lending to bor rowing countries and gave rise to demands on the part of the former for the repayment of maturing obligations. The borrowing countries experienced at first great difficulty in making remit tances, as was indicated by the position of and the fluctuations in the exchanges.

Later, as purchases of war supplies by the belligerents in creased, this difficulty disappeared and the exchanges turned in favour of the borrowing countries. From that time the European belligerent countries were confronted with an increasingly serious problem of financing their purchases abroad. It was a problem much more serious for the Allies than for the Central Powers, be cause the latter were largely cut off from the possibility of import ing from countries out of Europe; but it applied to the Central Powers in connection with their purchases from European neutrals.

Great Britain bore a large part of the burden of financing the external purchases of the Allies prior to the entry of the United States into the war, and an account of the arrangements made forms part of the history of British war finance (see GREAT BRITAIN). So far as purchases could not be paid for out of ordinary credit items in the trade account they were met out of money obtained (a) by selling abroad holdings of foreign securi ties, (b) by borrowing abroad on the market, or (c) by borrowing from foreign or Dominion Governments. Each method was adopted so far as practicable, the last becoming commoner as more countries joined the Allies.

In view of the magnitude of British investments overseas it might have appeared that vast sums could be raised abroad by the sale of securities if not by borrowing. The extent to which investments could be realized was, however, in fact comparatively small. Only exceptionally did it prove possible to sell any of the sterling securities which represented the bulk of British holdings, and sales were for the most part limited to securities expressed in (or convertible into) foreign currencies—particularly Amer ican dollar securities. The sale of these securities proceeded to some extent in response to ordinary economic motives, and sub sequently the British Government itself organized the acquisition, by purchase or on loan, of suitable dollar and other securities which could either be sold abroad or used as collateral for ad vances. To encourage holders to lend securities which the Gov ernment wished to borrow, an inducement was offered in the form of an additional 2 % interest ; while holders of certain specified securities were pressed to sell or lend them to the Treasury by means of a penal additional income tax of 2S. in the f.

In the course of its operations the so-called American Dollar Securities Committee purchased American and Canadian dollar securities to the value of £184,266,540, and obtained the deposit on loan of others valued at £100,290,052. More important in amount than the sale of American and other securities was the direct borrowing by the floating of loans abroad and by arrange ments with foreign bankers or with governments. The aggregate external debt of the British Government amounted on March 31, r919, to £1,364,850,000 at par of exchange. Of this £840,822, 000 represented debt owing to the United States Government, 191,808,000 was owing to the Canadian Government and 1113, 500,000 represented loans from certain Allied Governments, which could be regarded as available to be set off against debts owed by the same Governments to Great Britain.

Britain, France and Germany as Creditor Nations.— While dollar securities were being sold abroad and money was be ing borrowed, advances were being made to European Allies and to certain of the Dominions, the aggregate nominal amount of these advances being undoubtedly in excess of the amount raised abroad by selling securities and by borrowing. Regarded as a commercial asset, however, these advances are by no means equivalent in value to the amount realized by the sales of dollar securities and by external borrowings. In 1926 the payment made by Great Britain to the United States Government on account of principal and interest of the debt alone exceeded by over .16,500,00o the amount received by Great Britain in respect of war debts and reparations. On the whole, it is clear that the creditor position of Great Britain at the end of the war was con siderably, though certainly not fundamentally, impaired.

The effects of the war upon the creditor position of France were more disastrous owing to the extent to which French capital had been invested in Russia and other countries affected by the war. In addition to incurring considerable debts to private in terests, abroad, the French Government borrowed very heavily from the British and United States Governments. Settlements of these debts have been negotiated though not ratified by France, and payments on account have been terminated.

Germany, like France, had large investments in Russia which were lost. She also suffered from the sequestration of German property and enterprises in the territory of hostile countries, though to some extent this was set off against property of those governments associated with it in the war exceeded $7,300,000,000 at the end of 1918. Agreements were subsequently reached with nearly all the foreign governments to which money had been lent by the United States Treasury, for the settlement of their debts; but in 1931 President Hoover and Congress found it necessary to grant a year's moratorium, after which no nation except Finland resumed full payments. At the end of the war the United States was no longer on balance a debtor. During the following years she rapidly established her position as a great creditor. After the Armistice, Europe needed large quantities of foodstuffs and other supplies for which payment could not be made in cash. The United States was able and willing to furnish the goods and did so to a large extent on open credits from the banks. These ad vances were subsequently in large part funded in various ways. To some extent they were liquidated by further sales of European owned dollar securities, of which it is estimated that $5oo,000, 00o were repurchased in 1919 and 1920. A certain quantity of South American, Canadian and other sterling securities were also purchased in America.

Flotations of Capital.

Flotations of capital were effected in the United States to a vast aggregate amount on behalf of foreign governments and municipalities whether Canadian, South Amer ican, European or other; and large sums were invested in indus trial undertakings, especially in Canada and South America. The amount of new flotations of capital in 1928, 1929 and 1930, according to the U. S. Statistical Abstract were as follows :— countries in Germany sequestrated by the German Government. Like the Allies, Germany incurred heavy debts in certain foreign countries, notably Holland, Sweden and Switzerland ; and she mobilized saleable foreign securities with a view to effecting pay ments abroad. On the other hand, she advanced large sums to her Allies, but had to forego her claims to repayment as one of the conditions of peace. Her defeat in the war resulted in the loss of her position as a capital exporting country.

Position of Neutrals.

The urgent demands of the European belligerents for supplies of many kinds provided an exceptional opportunity for countries which were in a position to take ad vantage of it. This applied to a considerable extent to some of the neutral countries of Europe, especially Holland, Sweden and Switzerland; but their capacity to furnish supplies on loan or otherwise was restricted by economic difficulties resulting from their position in the war area. It was estimated nevertheless with regard to Switzerland that by the end of 1918 she had lent the Allies fr. 400,000,000 and the Central Powers fr. 200,000,00o, and that she had at the same time repurchased securities in French, German, English and Austrian hands to the value of at least 800,000,000 francs. The experience of Holland and Sweden was not dissimilar.

The United States as a Creditor Country.

It has already been indicated that for some years before the war, America had been investing capital abroad, although she was not on balance a capital exporting country. Clearly, however, her financial strength was increasing, and it was only the great demand for capital for internal development which kept her from becoming a capital exporting country. The war greatly hastened her prog ress in that direction. She was able to repurchase with ease from Europe large amounts of American securities, the aggregate being estimated at $2,000,000,000 up to the end of 1918. Private loans were also floated in the United States to the amount of $1,500, 000,000, while advances by the United States Government to the The flotation of new foreign capital issues fell off markedly in 1923, owing largely to distrust arising out of the French occu pation of the Ruhr. Following the settlement on the lines of the Dawes Report, which increased confidence in the stability of Europe, the amount of new issues rose to unprecedented figures in and 1926, when very large sums were lent to European governments and municipalities as well as to industrial enterprises. Parts of these new issues were, however, subse quently sold back to Europe.A large part of the gross export of capital from the United States (as also from the United Kingdom) is ordinarily repre sented by money subscribed to new flotations of capital for in vestment abroad. Nevertheless the gross export of capital is not to be identified with the amount of such flotations, even assuming them to be fully subscribed. Capital may be invested abroad privately, either in permanent investments or on short loan in foreign money markets. On the other hand, a new flotation may represent merely a sale of an undertaking which is already owned in the investing country, or part of the money may be subscribed by foreigners, or the subscription may be made out of funds already invested abroad. Still less is the amount subscribed to new flotations for investment abroad to be identified with the net export of capital, since there may, during any period, be a considerable import of capital. The amount of the net export of capital from the United States was estimated by the Department of Commerce, on the basis of an analysis of the international pay ments of the United States, to be $2,017,000,000 in 1920, and $378,000,000 in 1922. In 1923 there was a net import of capital amounting to $33,000,000 followed by a net export of $517,000, 000 in 1924, $621,000,000 in 1925, $181,000,000 in 1926, 000,000 in in 1928, $306,000,000 in 1929, and $614,000,000 in 1930. It is clear that the amount of new flota tions bears little relation to the net export of capital.

American foreign investments (exclusive of debts owing by foreign governments to the United States Government) are estimated to have been made up as follows, at the end of 1926: $ Europe 3,010,000,00o Latin America . 4,500,00o,000 Canada and Newfoundland 2,801,000,000 Asia, Australia, Africa and rest of the world. 904,000,000 11,215,000,000 By far the greater part of these investments has been made since 1914, and when account is taken of the fact that foreign holdings of investments in America have been reduced to com paratively small proportions by the repurchase of some $2,500, 000,000 of securities, and further of the debts owing by European Governments, the magnitude of the change which had occurred in the financial position of the United States is clearly apparent. Due to the great depression which occurred in the United States in the period between 1929 and the outbreak of war in 1939, America exported little capital. Imports of gold and capital for safety came from almost every country in Europe except Italy, Germany, and Spain from 1937 to France and Germany in Post-War Finance.—For the decade after the war Europe ceased to be able to provide large amounts of capital for other parts of the world, and on the whole the flow was instead rather into than away from Europe. The re sources of France were fully taken up with the restoration of the devastated areas. Germany had to borrow heavily for reconstruc tion, and having regard to reparation payments was in no position to invest capital abroad during those years, nor at any time since.

Recovery of the London Market.

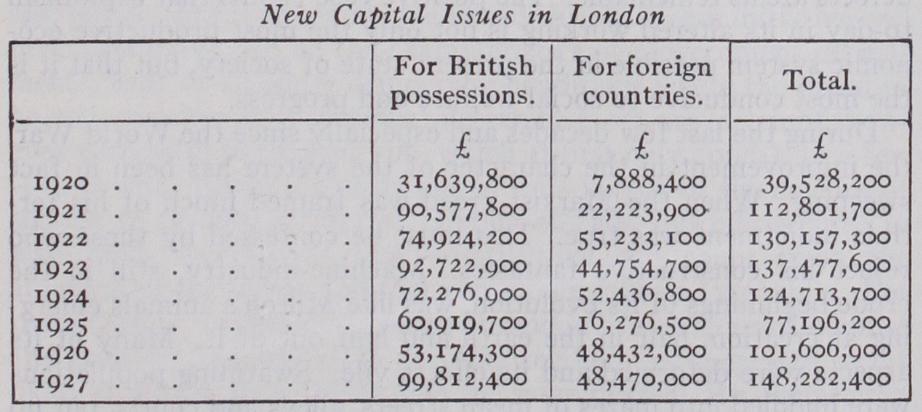

On the other hand, Great Britain was able to resume the export of capital, though on a reduced scale. The external debt incurred during the war was reduced by over £ 200,000,000 between March 1919 and March 1921, since when further substantial reductions have been made. During 1920 considerable blocks of South American, Chinese and other foreign securities were purchased at low prices from the Continent, although at the same time other securities were being sold to the United States and also to Canada until the imposition by the latter country in the autumn of 1920 of an embargo on importation of securities. Considerable flotations of capital were also made for British possessions and foreign countries, as indi cated by figures compiled by The Economist, shown in tabular form : "New Capital Issues in London." For reasons explained above the amount of new issues of capital for investment abroad is not to be identified with the total export of capital, and still less with the net export of capital obtained after deducting any import of capital. There is reason to believe that during a part of this period a considerable im port of capital had taken place (in the form of a transfer to London of bankers' and other balances for investment in the money market) tending to offset the total export of capital repre sented by capital subscribed to new issues and other investments.

Estimates of the export of capital based upon an analysis of the balance of trade indicate that in 1920 the nominal amount was probably higher than in the years immediately preceding the war, when it approached £ 200,000,000 per annum. In 1922 the amount was probably about the later figure and in 1923 about £170,000,000. It fell to f86,000,000 in 1924 and £54,000,000 in 1925, according to estimates of the Board of Trade. In 1926, when the trade of the country was disorganized by a prolonged coal stoppage, it is estimated by the same authority that there was a net import of capital amounting to approximately L7,000, 000. The general depression of trade has affected British indus try severely, and while the aggregate accumulation of capital has certainly been much reduced in real amount (though in nominal value it is probably as great as before the war) a much larger proportion has been invested in Great Britain. In 1939 the out break of war again violently disturbed the normal flow of capital between nations.