Megalithic Monuments

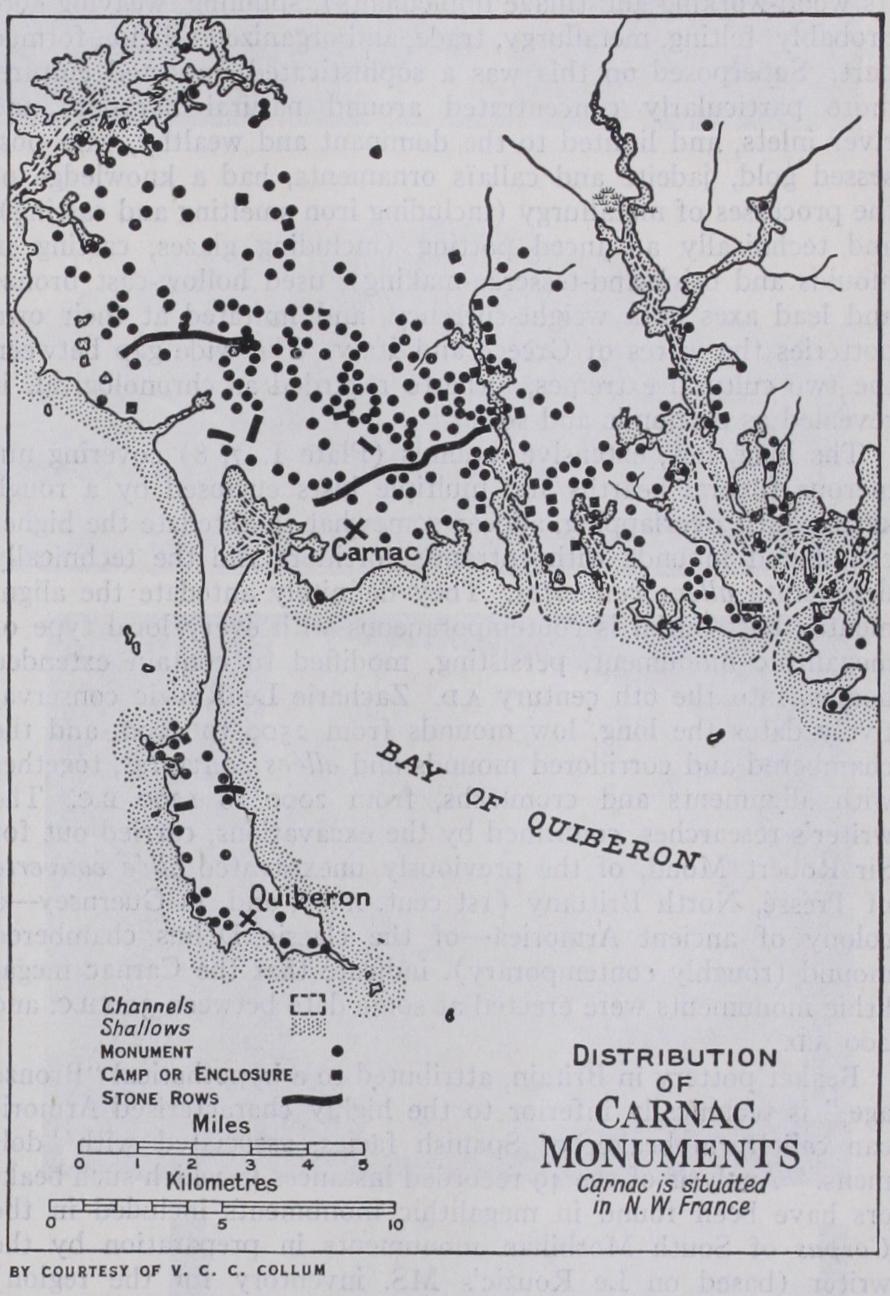

MEGALITHIC MONUMENTS Alignments of standing stones, isolated menhirs, chambered mounds, and "dolmens" denuded of their mounds, survive in the Carnac district in greater number and variety than anywhere else. (See figure for relationship to.sea-coast and deep water inlets.) The Societe Polymathique du Morbihan (Museum at Vannes) started excavating them nearly a century ago. W. C. Lukis of Guernsey (finds in the British Museum) and James Miln of Scot land also studied them. Miln bequeathed his finds to Carnac. He had for pupil a Carnac boy, Zacharie Le Rouzic, afterwards Con servator of the Miln-Le Rouzic museum. Archaeology owes most of its actual knowledge of the monuments to his re-excavations and restorations during the past 4o years. (Interesting selections of finds from Carnac are also exhibited in the museum of National Antiquities, St. Germain-en-Laye.) The theoretical chronology of the monuments, deduced from an ideal typology starting with the "stone age" slab-kist and evolving into chambered mounds of the Petit Mont (G. xxvi. 14) and Ile Longue (H. xxix. 23) type, has been undermined no less by Le Rouzic's patient collec tion and juxtaposition of his finds than by the re-examination of the early excavators' original reports and the subsequent method ical analysis of all the association data available, a task that has occupied the writer for nine years. The evidence demonstrates that the monuments were built by a mixed population trading with the megalithic centres of Grand-Pressigny (Touraine), the Iberian peninsula, and northwest Britain and Ireland, influ enced culturally by the Aegean and the nomads of northern Eu rasia. The native maritime people were slightly-built and very long-headed. They lived largely by fishing and shell-fish collect ing, used roughly-fashioned flint, bone and horn implements, and microlithic flakes, and commonly buried their dead crouched, in walled-up rock-shelters or graves made box-wise of slabs or dug out and lined with boulders (Plate II. 4) ; but they also had do mestic animals and grain. Their pottery and polished stone im plements included styles contemporaneous with the knowledge of metal. Intermingled and interbred with them was the sturdily built, broad-headed race everywhere associated with a metal-using culture. Members of a taller race, conspicuous for its large bones, prominent nose and big teeth associated with certain primitive anatomical features, also dwelt among them. Alongside of the crouched inhumation rite of the long-headed slender race, characterizing chambered mound and slab-kists alike, existed that of incineration and urn burial in association with similar objects; this rite again overlapped that of extended inhumation. In the megalithic tombs the principal burial was beneath the floor of the main chamber, but other bodies were disposed on the chamber floors in circumstances suggesting a voluntary holocaust. Horses and cattle were slaughtered as part of the funeral rite; sometimes they were ceremonially buried. as horses at Mane Lud (A. ii. 9) and oxen at Mont St. Michel (F. xix. 2). Certain data point to a ritual burning consistent with roasting at a funeral fire followed by a feast and the carrying away by guests of surplus meat. Rough pottery was ritually made and flints knapped on the spot, and votive objects, including wheel-turned vessels and exquisite jade axeheads, were deposited in the chambers. The constructors of these monuments enjoyed a basic civilisation that had spread all over inhabited Europe in an age when the natives were still in the transition stage from a hunting and fishing existence (when they were ignorant of metal) to the sedentary culture complex of which pottery, agriculture and stock-raising (with its wood-working and tillage implements), spinning, weaving and, probably, felting, metallurgy, trade, and organized religion formed part. Superposed on this was a sophisticated imported culture, more particularly concentrated around natural harbours and river inlets, and limited to the dominant and wealthy, who pos sessed gold, jadeite and callais ornaments, had a knowledge of the processes of metallurgy (including iron smelting and casting), and technically advanced potting (including glazes, casting in moulds and brick-and-tesserae-making), used hollow-cast bronze and lead axes as a weight-currency, and imitated at their own potteries the wares of Greece and Italy. The wide gap between the two cultural extremes, hitherto regarded as chronological, is revealed as economic and social.

The long, low, extensive mounds (Plate I. 7, 8) covering nu merous funeral hearths and multiple kists enclosed by a rough kerb, whilst overlapping, appear somewhat to antedate the higher chambered mounds with entrance corridors and the technically degenerate allees couvertes. They definitely antedate the align ments. Kist burial is contemporaneous with every local type of megalithic monument, persisting, modified to contain extended bodies, into the 6th century A.D. Zacharie Le Rouzic conserva tively dates the long, low mounds from 2 50o to 2000, and the chambered and corridored mounds and allees couvertes, together with alignments and cromlechs, from 2000 to 1200 B.C. The writer's researches, confirmed by the excavations, carried out for Sir Robert Mond, of the previously unexcavated allee couverte of Tresse, North Brittany (1st cent. A.D.), and, in Guernsey—a colony of ancient Armorica—of the classic Dehus chambered mound (roughly contemporary), indicate that the Carnac mega lithic monuments were erected at some date between 30o B.C. and 200 A.D.

Beaker pottery in Britain, attributed to a hypothetical "Bronze age," is technically inferior to the highly characterised Armori can caliciform beaker of Spanish facies, associated with "dol mens." Analysis of the 49 recorded instances in which such beak ers have been found in megalithic monuments included in the Corpus of South Morbihan monuments in preparation by the writer (based on Le Rouzic's MS. inventory for the region) brings out the variation in the contemporary architectural models and illustrates this telescoping of hypothetical "ages." Five were allees couvertes, in 2 cases bent and in 1 having a porthole. Six of the chambers were corbelled, in 3 cases being enclosed in the same mound with a "dolmen"-style chamber built of massive stone up rights with coverstones. (Dry masonry is always associated with megaliths in unruined chambers; multi-chambered mounds are common.) In one case one wall was natural rock outcrop. The ground plans of these 49 monuments include almost all known European types. In them characterless flint chips and quartzite hammer-stones are general, associated (a) with unused polished local fibrolite, diorite, jadeite and chloromelanite axes, some be ing obvious copies of metal models ; (b) with unused scrapers, blades and barbed and tanged and also leaf-shaped arrowheads in Grand-Pressigny or other imported flint; (c) with evenly-bored cylindrical callais beads, and rougher beads in serpentine and talc; (d) with rock-crystals, and (e) with hammered gold orna ments decorated with repousse dots. With the recorded beakers were associated, in 7 cases, black handmade Gaulish pottery (associated with gold twice, with a copper dagger once, with wheel-turned ware thrice) ; in 4 cases handmade "black-leaded," and in 5 cases, wheel-turned "black-leaded" ware (these associated, respectively, with gold and iron in 1 instance, with a bronze tinkle-bell in I ; with gold in 1, and in another with a corrugated cylindrical bead, apparently of metal with an enamel copper based glaze on the exterior surface only, a yellow glass bead, and a scrap of bronze) ; in 8 cases with wheel-turned Gaulish pottery of Roman Occupation date (associated with iron and a bronze awl in I case, Gaulish coins, glass and pipe-clay Gaulish statuettes in another, and with similar statuettes in 2 further cases, and in yet another with bronze and lead and Gaulish brick-tiles). In 6 instances the beakers were associated with pottery of "Iron age" facies (in 1 instance associated with bronze riveted swords and beaten gold collars), and in 2 with the peculiar pedestal offering stands of highly-fired ware manufactured at the Er-Lannic site (G. xxvi. I 5), these stands themselves associated in i case with the before-mentioned statuettes and glass.

In 2 cases the beakers were associated with potter's clay, in 4 further cases with gold ornaments (in i instance associated with a fragment of tortoise-shell and in another with a schist wrist guard), and in I case with a Gallo-Roman glass phial. Thus in 26 instances out of the 49 there were other objects dating the monument to Gaulish times.

This analysis is limited to beaker associations and takes no ac count of the numerous instances in which datable Gaulish objects were found associated with other types of handmade pottery, flints and votive stone axes. Le Rouzic's excavations have demon strated that the horse-shoe cromlechs enclosed human habita tions, and that, at the Er-Lannic cromlechs, were produced hard stone votive axes and cylindrical offering-stands like those found in situ in the Hougue Bie chamber in Jersey, and in fragments in some Carnac monuments. Folklore associates these enclosures with assemblies and dancing. The alignments, by no means straight, usually lead up to such enclosures (some of them vast in area), the taller stones, up to 5 metres high, nearest the en closure. The Kerlescan group (13 lines and 88o m. long) still contains 540 stones, the Kermario group 982, and the Menec group 1,099 (not to mention others). Possibly they were social memorials set up along the route from a settlement to a boat landing. (See Plate.) Recent excavations reveal several habita tion sites in which Gaulish and "Iron age" pottery is associated with objects found in the megalithic tombs. Hill-top and prom ontory refuge "camps," adjacent to channels, yield similar objects.

The seemingly anomalous Carnac data are all susceptible of a logical explanation if we assume. that the Veneti of Armorica, whose great sailing ships, iron anchors and chains, and far-flung trade so impressed Caesar, were an off-shoot from their name sakes sited on the Adriatic where sea-routes from the Aegean met continental trade routes from the Black Sea. The signs sculp tured on the megaliths of the tombs suggest by their symbolism a cult derived from an Oriental cosmic theosophy spread far and wide during the period 60o B.C. to 400 A.D., in which Hermes and his emblem (Plate II. I.)—to whose frequency in Gaul Caesar called attention—played a propagative part. In Roman times the megalithic chambers were doubtless still enveloped in their mounds which would excite little comment among a people fa miliar with funeral tumuli at home. Their violation was probably begun by the Northern pirates who devastated Armorica, and they appear to have proved a lucrative source of "hidden gold" to the enterprising, pirates or others all down the centuries from that time to this.