Cathedral

CATHEDRAL, more correctly "cathedral church" (ecclesia cathedralis), the church which contains the official "seat" or throne of a bishop—cathedra, one of the Latin names for this, giving us the adjective "cathedral." The adjective has gradually, for briefness of speech, assumed the character of a substantive.

History and Organization.

It was early decreed that the cathedra of a bishop was not to be placed in the church of a village, but only in that of a city. There was no difficulty as to this on the continent of Europe, where towns were numerous, and where the cities were the natural centres from which Christianity was diffused among the people who inhabited the surrounding districts. In the British isles, however, the case was different ; towns were few and, owing to other causes, instead of exercising jurisdiction over definite areas or districts, many of the bishops were bishops of tribes or peoples, as the bishops of the South Saxons, the West Saxons, the Somersaetas and others. The cathedra of such a bishop was often migratory, and was at times placed in one church, and then another, and sometimes in the church of a village. In 1075 a council was held in London, under the presidency of Archbishop Lanfranc, which, reciting the decrees of the council of Sardica held in 347 and that of Laodicea held in 36o on this matter, ordered the bishop of the South Saxons to remove his see from Selsey to Chichester ; the Wilts and Dorset bishop to remove his cathedra from Sherborne to Old Sarum, and the Mercian bishop, whose cathedra was then at Lichfield, to transfer it to Chester. Traces of the tribal and migratory system may still be noted in the designations of the Irish see of Meath (where the result has been that there is now no cathedral church) and Ossory, the cathedral church of which is at Kilkenny. Some of the Scottish sees were also migratory. Occasionally two churches jointly share the distinction of containing the bishop's cathedra. In such case they are said to be con-cathedral in rela tion to each other. Instances of this occurred in England before the Reformation in the dioceses of Bath and Wells, and of Cov entry and Lichfield. Hence the double titles of those dioceses. in Ireland an example occurs at Dublin, where Christ Church and St. Patrick's are jointly the cathedral churches of that diocese. Cathedral churches are reckoned as of different degrees of dignity : (t) the simple cathedral church of a diocesan bishop, (2) the metropolitical church to which the other diocesan cathedral churches of a province are suffragan, (3) the primatial church under which are ranged metropolitical churches and their prov inces, (4) patriarchal churches to which primatial, metropolitical and simple cathedral churches alike owe allegiance. The title of "primate" was occasionally conferred on metropolitans of sees of great dignity or importance, such as Canterbury, York, Rouen, etc., whose cathedral churches remained simply metropolitical. The removal of a bishop's cathedra from a church deprives that church of its cathedral dignity, although often the name clings in common speech, as for example at Antwerp, which was deprived of its bishop at the French Revolution.The history of the body of clergy attached to the cathedral church is obscure, and as in each case local considerations affected its development, all that can be attempted is to give a general outline of the main features which were more or less common to all. Originally the bishop and cathedral clergy formed a kind of religious community, which, in no true sense a monastery, was nevertheless often called a monasterium. The word had not the restricted meaning which it afterwards acquired. Hence the ap parent anomaly that churches like York and Lincoln, which never had any monks attached to them, have inherited the name of minster or monastery. In these early communities the clergy often lived apart in their own dwellings, and were not infrequently married. During the two centuries, roughly bounded by the years 90o and t too, the cathedral clergy became more definitely organ ized, and were also divided into two classes. One was that of a monastic establishment of some recognized order of monks, very often that of the Benedictines, while the other class was that of a college of clergy, living in the world, and bound by no vows, ex cept those of their ordination, but governed by a code of statutes or canons. Hence the name of "canon" given to them. In this way arose the distinction between the monastic and secular cathedral churches. In England the monastic cathedral churches were Bath, Canterbury, Carlisle, Coventry, Durham, Ely, Nor wich, Rochester, Winchester and Worcester, all of them Benedic tine except Carlisle, which was a church of Augustinians. The secular churches were Chichester, Exeter, Hereford, Lichfield, Lincoln, St. Paul's (London), Salisbury, Wells, York and the four Welsh cathedral churches. In Ireland all were secular except Christ Church, Dublin (Augustinian) and Down (Benedictine), and none, even in their earliest days, were ever, it is believed, churches of recognized orders of monks, except the two named. In Scotland St. Andrew's was Augustinian, Elgin (or Moray), Glasgow and Aberdeen were always secular, and ordered on the models of Lincoln and Salisbury. Brechin had a community of Culdees till 1372, when a secular chapter was constituted. The cathedral church of Galloway, at Whithorn, of English foundation, was a church of Praemonstratensians. In the case of monastic cathedral churches there were no dignitaries, the internal govern ment was that of the order to which the chapter belonged, and all the members kept perpetual residence. The reverse of this was the case with the secular chapters; the dignities of provost, dean, precentor, chancellor, treasurer, etc., soon came into being, for the regulation and good order of the church and its services, while the non-residence of the canons, rather than their perpetual resi dence, became the rule, and led to their duties being performed by a body of "vicars," who officiated for them at the services of the church.

The normal constitution of the chapter of a secular cathedral church comprised four dignitaries (there might be more), in addition to the canons. The dean (decanus) seems to have derived his designation from the Benedictine dean who had ten monks under his charge. The dean, as already noted, came into existence to supply the place of the provost in the internal management of the church and chapter. In England the dean was the head of all the secular cathedral churches, and was originally elected by the chapter and Confirmed in office by the bishop. He is president of the chapter, and in church has charge of the due per formance of the services, taking specified portions of them by statute on the principal festivals. He sits in the chief stall in the choir, which is usually the first on the right hand on entering the choir at the west. Next to the dean (as a rule) is the precentor (primicerius, cantor, etc.), whose special duty is that of regulat ing the musical portion of the services. He presides in the dean's absence, and occupies the corresponding stall on the left side, although there are exceptions to this rule, where, as at St. Paul's, -the archdeacon of the cathedral city ranks second and occupies what is usually the precentor's stall. The third dignitary is the chancellor (scholasticus, ecoldtre, capiscol, magistral, etc.), who must not be confounded with the chancellor of the diocese. The chancellor of the cathedral church is charged with the oversight of its schools, ought to read divinity lectures, and superintend the lections in the choir and correct slovenly readers. He is of ten the secretary and librarian of the chapter. In the absence of the dean and precentor he is president of the chapter. The eastern most stall, on the dean's side of the choir, is usually assigned to him. The fourth dignitary is the treasurer (custos, sacrista, che(icier) . He is guardian of the fabric, and of all the furniture and ornaments of the church, and his duty was to provide bread and wine for the eucharist, and candles and incense, and he regu lated such matters as the ringing of the bells. The treasurer's stall is opposite to that of the chancellor. These four dignitaries, occupying the four corner stalls in the choir, are called in many of the statutes the "quatuor majores personae" of the church. In many cathedral churches there were additional dignitaries, as the praelector, subdean, vice-chancellor, succentor-canonicorum and others, who came into existence to supply the places of the other absent dignitaries, for non-residence was the fatal blot of the secular churches, and in this they contrasted very badly with the monastic churches, where all the members were in continuous residence. Besides the dignitaries there were the ordinary canons, each of whom, as a rule, held a separate prebend or endowment, besides receiving his share of the common funds of the church. For the most part the canons also speedily became non-resident, and this led to the distinction of residentiary and non-residentiary canons, till in most churches the number of resident canons be came definitely limited in number, and the non-residentiary canons, who no longer shared in the common funds, became gen erally known as prebendaries only, although by their non-residence they did not forfeit their position as canons, and retained their votes in chapter like the others. This system of non-residence led also to the institution of vicars choral, each canon having his own vicar, who sat in his stall in his absence, and when the canon was present, in the stall immediately below, on the second form. The vicars had no place or vote in chapter, and, though irremovable except for offences, were the servants of their absent canons whose stalls they occupied, and whose duties they performed. Abroad they were often called demi-prebendaries, and they formed the bas choeur of the French churches. As time went on the vicars were themselves often incorporated as a kind of lesser chapter, or college, under the supervision of the dean and chapter. There was no distinction between the monastic cathedral chapters and those of the secular canons, in their relation to the bishop or diocese. In both cases the chapter was the bishop's consilium which he was bound to consult on all important matters and with out doing so he could not act. Thus, a judicial decision of a bishop needed the confirmation of the chapter before it could be en forced. He could not change the service books, or "use" of the church or diocese, without capitular consent, and there are many episcopal acts, such as the appointment of a diocesan chancellor, or vicar general, which still need confirmation by the chapter.

All the English monastic cathedral chapters were dissolved by Henry VIII., and, except Bath and Coventry, were refounded by him as churches of secular chapters, with a dean as the head, and a certain number of canons ranging from twelve at Canterbury and Durham to four at Carlisle, and with certain subordinate officers as minor canons, gospellers, epistolers, etc. The precentor ship in these churches of the "New Foundation," as they are called, is not, as in the secular churches of the "Old Foundation," a dignity, but is merely an office held by one of the minor canons.

English cathedral churches, at the present day, may be classed under four heads : the old secular cathedral churches of the "Old Foundation," enumerated in the earlier part of this article ; (2) the churches of the "New Foundation" of Henry VIII., which are the monastic churches already specified, with the exception of Bath and Coventry ; (3) the cathedral churches of bishoprics founded by Henry VIII., viz., Bristol, Chester, Gloucester, Ox ford and Peterborough (the constitution of the chapters of which corresponds to those of the New Foundation) ; (4) modern cathedral churches of sees founded since 1836, viz., (a) Man chester, Ripon and Southwell, formerly collegiate churches of secular canons; (b) St. Albans and Southwark, originally mo nastic churches; (c) Truro, Newcastle and Wakefield, formerly parish churches, (d) Birmingham and Liverpool, originally dis trict churches. The ruined cathedral church of the diocese of Sodor (i.e., the Southern Isles) and Man, at Peel, in the Isle of Man, appears never to have had a chapter of clergy attached.

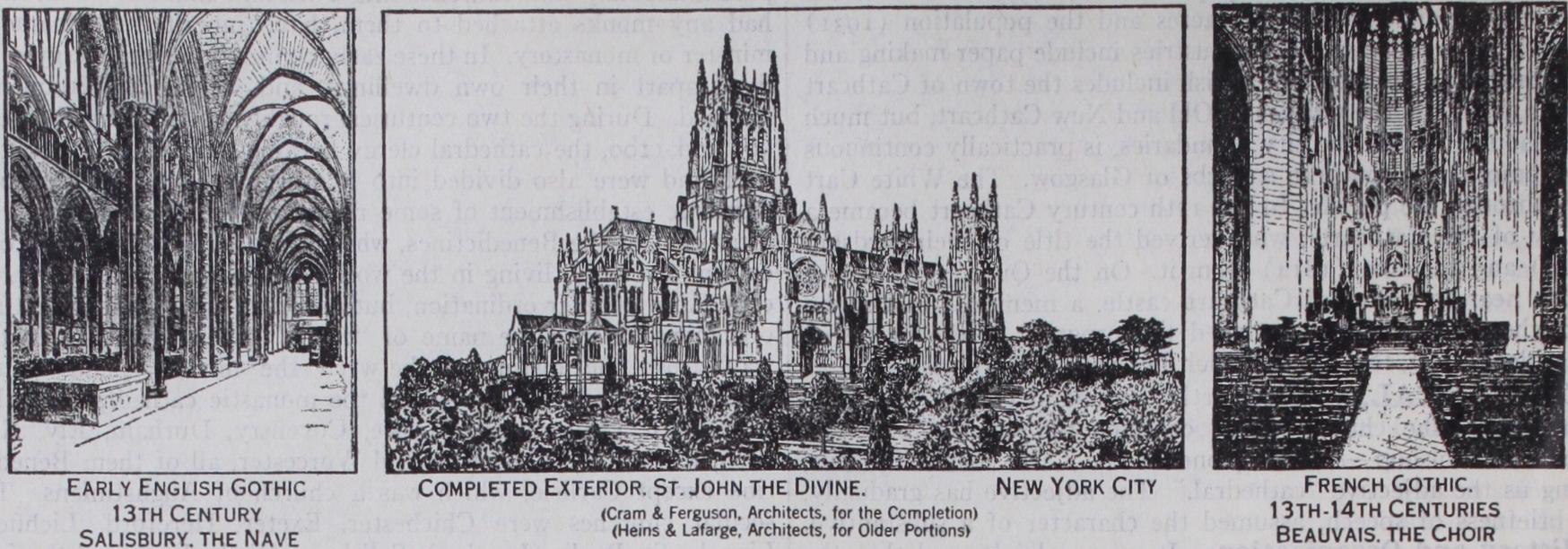

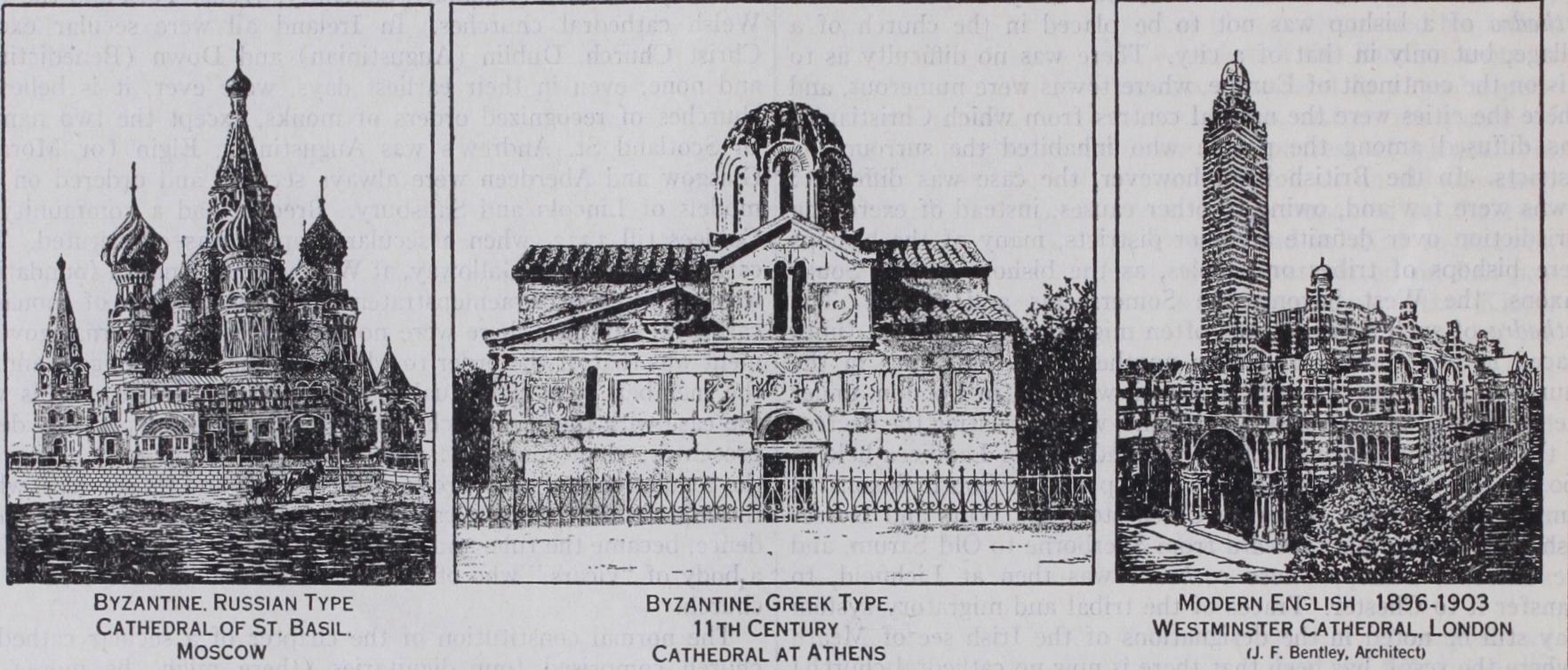

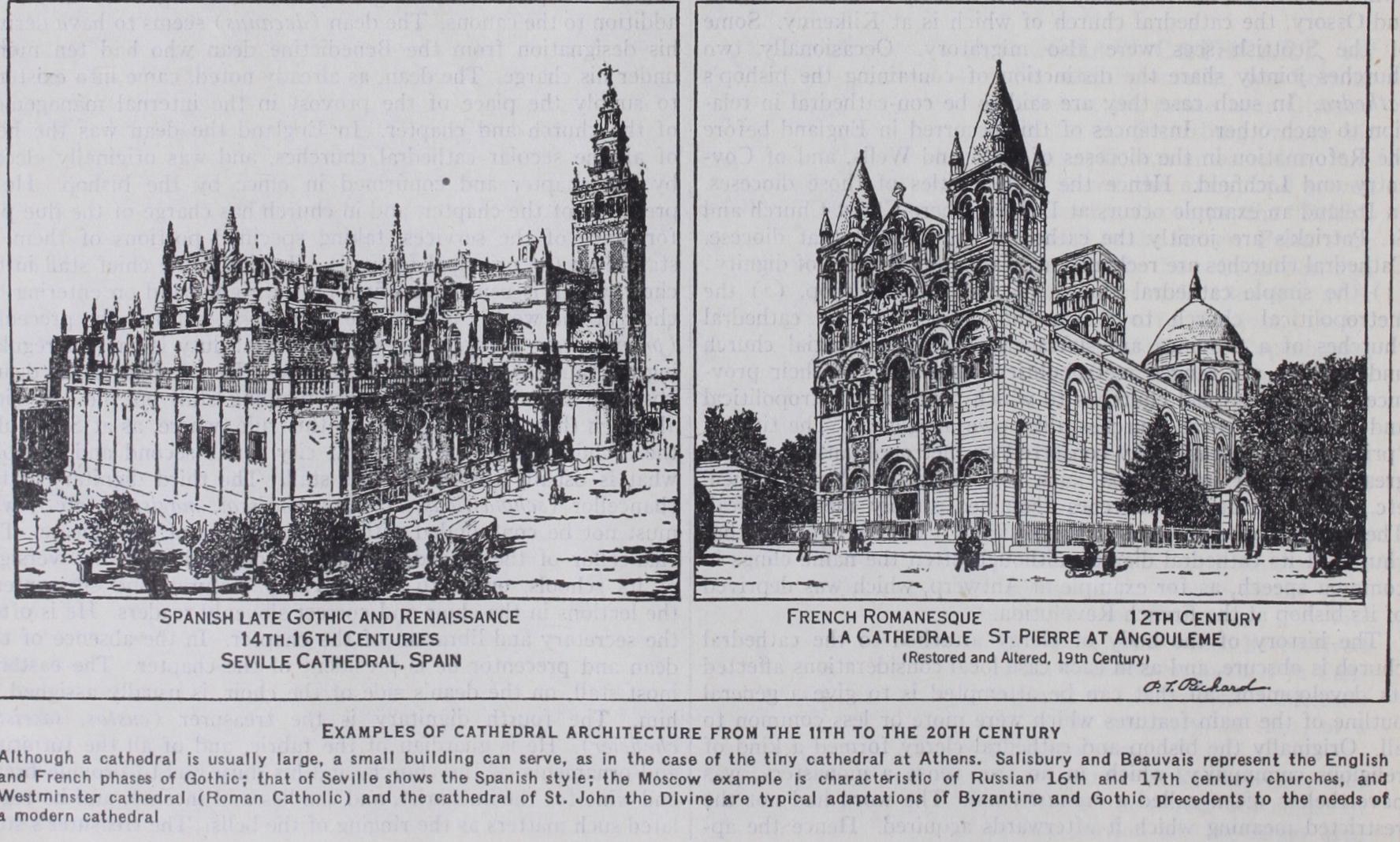

De ecclesiis cathedralibus (Venice, 1698) ; Bordenave, L'Estat des eglises cathedrales (Paris, 1643) ; Van Espen, Supplement III., cap. 5; Hericourt, Les Loix ecclesiastiques de France (Paris, 1756) ; La France ecclesiastique (Paris, 179o) ; Daugaard, Om de Danske Klostre i Middelalderen (Copenhagen, 183o) ; Hinschius, Das Kirchenrecht der Katholiken u. Protestanten in Deutschland, ii. (Berlin, 1878) ; Walcott, Cathedralia (London, 1865) ; Freeman, Cathedral Church of Wells (London, 1870) ; Benson, The Cathedral (London, 1878) ; Bradshaw and Wordsworth, Lincoln Cathedral Statutes (Camb., 1894). (X.; S. H. M.) Architecture.—The architectural importance of the cathedral arises not from any specific differences between cathedrals and other churches but from the fact that cathedral building is intimately associated with the development of Gothic architecture (see GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE) . The archaeologists of the late century considered the rise of the secular clergy in the I2th and 13th centuries the most important factor in the birth of Gothic architecture. Contemporary (1928) critical opinion dis counts this, and points out that Gothic ideas first had tentative expression in the abbey church of St. Denis, near Paris (I 140). It is nevertheless a fact that the construction of many large cathedral churches in France, in the second half of the I2th century, furnished architects with many new structural and aes thetic problems. Public opinion of the time, generally in revolt against the feudal domination of the great monasteries, broke the controlling sway of monastic architectural tradition, and lay archi tects became the rule rather than the exception. The development that followed in the half century between i i 5o and 1200, in which many discreet Romanesque experiments in vaulting, window and door design, stained glass, buttressing and planning, particularly of the east end, reached a compelling synthesis, is unique in architectural history. In the domain of the Eastern Church, where no such break between lay and monastic clergy occurred, it is significant that there was no such architectural development ; Russian cathedrals remained simple Russo-Byzantine churches up to the 18th century.

Recent times have witnessed the renascence of the idea of the cathedral as a great popular monument. This movement is evi denced in the magnificent Liverpool cathedral, designed by Sir Giles Gilbert Scott in a free and modernized Gothic style, and in the Gothic cathedral of S. John the Divine in New York, begun by Heinz and LaFarge and now (1928) entirely remodelled and in course of completion by Ralph Adams Cram; and that at 'Washington, D.C., by Frohman, Robb and Little. These great modern cathedrals differ from earlier examples in their recognition of the fact that in them the congregation is of relatively greater importance than the clergy and choir and the consequent attempt to obtain enormous open spaces as close as possible to the chancel. In general, the eastern arm and the transepts are thereby shorter than the usual Gothic proportion, whereas the crossing is given immensely greater importance. (See APSE; RELIGIOUS AND ME