Cattle

CATTLE. The word cattle was formerly used to embrace all farm live stock, but is now commonly restricted to oxen or meat cattle. The several animals that may be included under the term, in this narrower sense, are usually divided into the following six groups :—(1) Buffaloes (India, Africa, etc.) ; (2) Bison (Europe and North America) ; (3) the Yak (Thibet, etc.) ; (4) the Gaur, Gayal and Bantin (India and Further India) ; (5) Eastern and African domesticated cattle or Zebu; and (6) Western or Euro pean domesticated cattle. Apart from the two last mentioned groups the India buffalo, yak, gayal and bantin have been domes ticated, and the American bison is being tried as an economic ani mal. Apart from the buffaloes, which constitute a relatively primi tive and rather distinct type, all the species enumerated are rather closely related. The buffaloes do not hybridize with the members of the other groups, but all the rest can be interbred without diffi culty and the hybrids, or at least the female hybrids, are quite fertile. (See also BOVIDAE, BUFFALO, BISON, YAK, GAUR, GAYAL, BANTIN, OX, AUROCHS.) The ox was certainly one of the earliest—possibly the first—of all animals to be domesticated. As regards Western Europe there is no evidence of domestication in paleolithic times but there are plentiful remains in the Swiss lake dwellings and other deposits of neolithic age. Domesticated cattle existed in Egypt about B.C., and possibly much earlier, while Babylonian remains have been assigned to still more remote ages.

In all likelihood the wild ancestors of European domesticated cattle belonged to one or more of the sub-species of the aurochs or urus(Bos primigenius) which was widely distributed in Europe, Western Asia, and Northern Africa in prehistoric times. However, the earliest known domesticated ox in Europe was a very small, slenderly built animal, with short horns, bearing all the marks of a prolonged existence under the care of man and contrasting very markedly with the contemporary wild urus. The conclusion has been drawn that the original domestication did not occur in West ern Europe ; probably the little ox, (Bos longifrons or Bos brachy ceros) together with corresponding types of sheep and pig were brought from Asia by neolithic man in his migrations. Later, in the Bronze age particularly, a new and larger type of cattle, show ing a closer resemblance to the European wild ox, made its ap pearance. Probably the Bos longifrons had been "graded up" by crossing with the wild type. The process was, however, not uni versal, and even to-day breeds like the Shetland, Jersey, Kerry and Brown Swiss show a marked resemblance to the neolithic type.

Whether the zebu had a separate origin from the western ox is not known ; some authorities seek to relate it with the bantin or gayal. In shape, colour, habits, and even in voice, it presents many points of difference from western cattle ; but the most striking of these, such as the presence of a hump, or the upward inclination of the horns, are not constant. There exist in Africa, Spain, China, etc., breeds which are intermediate between zebu and European cattle, but it is likely that some at least of these have arisen by crossing. (J. A. S. \V.) The word "cattle," which ety mologically merely denotes a form of property and is practically synonymous with "chattel," is by common usage a generic term for animals of the bovine race. The history of domesticated cattle begins with the history of civilisation ; indeed, before the days of settled communities nomadic man possessed herds of cattle which represented his wealth. With the beginning of agriculture and the systematic cultivation of the land the ox was harnessed to the plough and it is still the draught animal of the farm through out the greater part of the world. Even in England it has been dis placed by the horse only within the past century and there are many persons still living who have seen oxen ploughing English land. The economic value of cattle arose from the docility of the males for draught and the aptitude of the females to supply milk in excess of the requirements of their offspring. Ultimately they were utilized as food but this was in a sense secondary, and among some races their flesh was regarded for religious or other reasons as unfit for human consumption. The breeding and rearing of cattle for the primary purpose of supplying meat is a modern development.

In the terminology used to describe the sex and age of cattle, the male is first a "bull-calf" and if left intact becomes a "bull"; but if castrated he becomes a "steer" and in about two or three years grows to an "ox." The female is first a "heifer-calf," grow ing into a "heifer" and becoming after two or three years a "cow." A heifer is sometimes operated on to prevent breeding and is then a "spayed heifer." The age at which a steer becomes an ox and a heifer a cow is not clearly defined and the practice varies. Both in the male and female emasculation is practised because the animals are assumed to fatten more readily ; in the case of bulls intended for use as working oxen the object of emasculation, as in the case of stallions, is to make them quieter and more tractable in work.

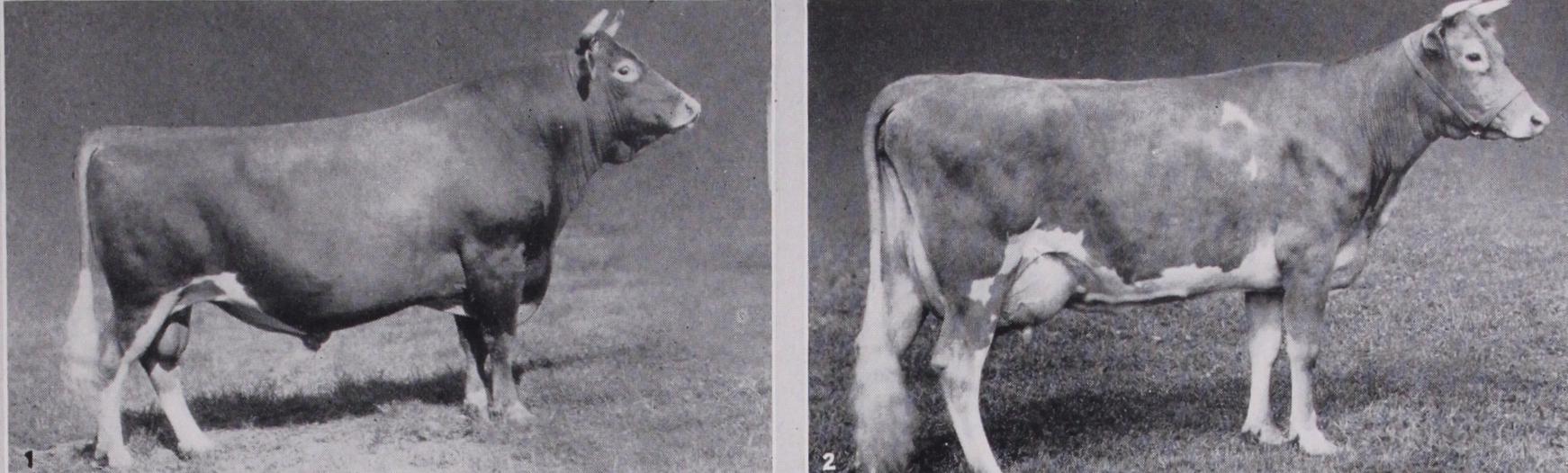

Breeds.—The exact definition of a "breed" of cattle is difficult, although the term is commonly used and in practice well under stood. It may be said generally to connote a particular type of animal which has for a long period been bred only with those of the same, or closely similar type, and has hereditary characteristics which are transmissible to its offspring. In every breed, however long established, instances of atavism may and do occur, but these are eliminated and do not affect its general purity. Breeds have been established by generations of cattle-breeders aiming at the attainment and preservation of a particular type and working on the principle that "like begets like." It is only within very recent times that the laws of heredity founded on the researches of Mendel have been studied as a science. There are many old-estab lished breeds on the Continent as for example the Charolais and Normande of France, the Holsteins of Holland, the Campagna di Roma of Spain, and many others, but the British breeds are of most interest because of their influence in building up the vast herds which furnish the supplies of beef on which other countries are largely dependent. (See BEEF).

There are in the British Isles 20 breeds recognized by separate classes at the annual show of the Royal Agricultural Society. They are the following : To this list should be added the Highland breed for which classes are provided at the annual show of the Highland and Agri cultural Society of Scotland. Some of these breeds are limited in number and restricted in locality but each has its own character istic merits as may be seen by noting the salient features of the more important of them.

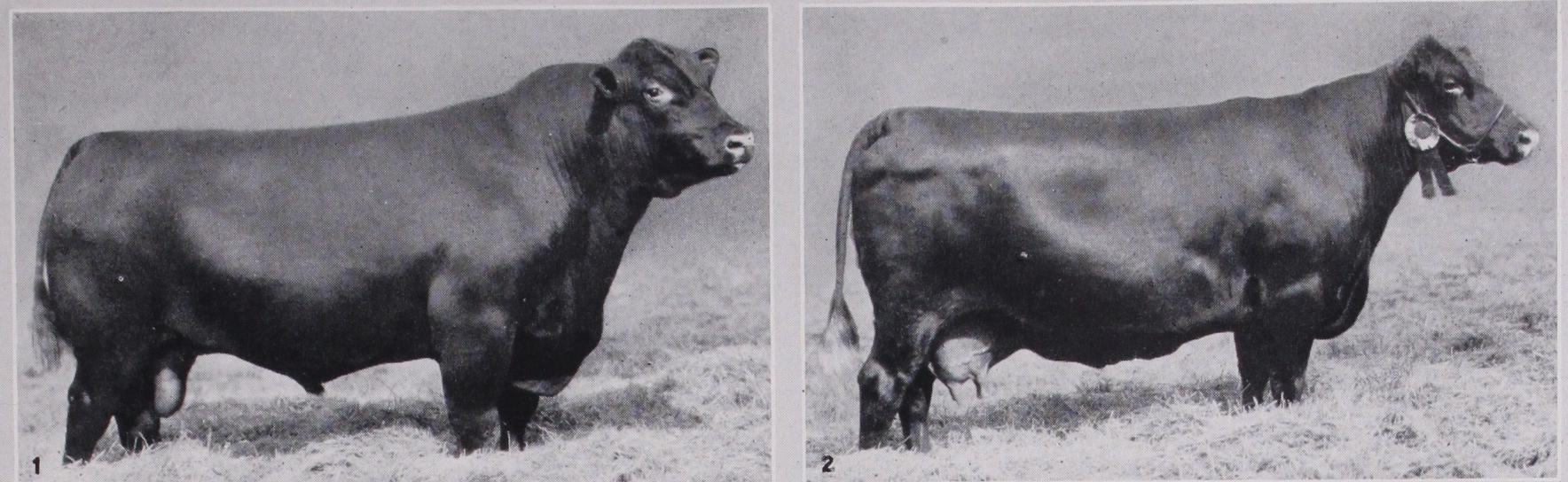

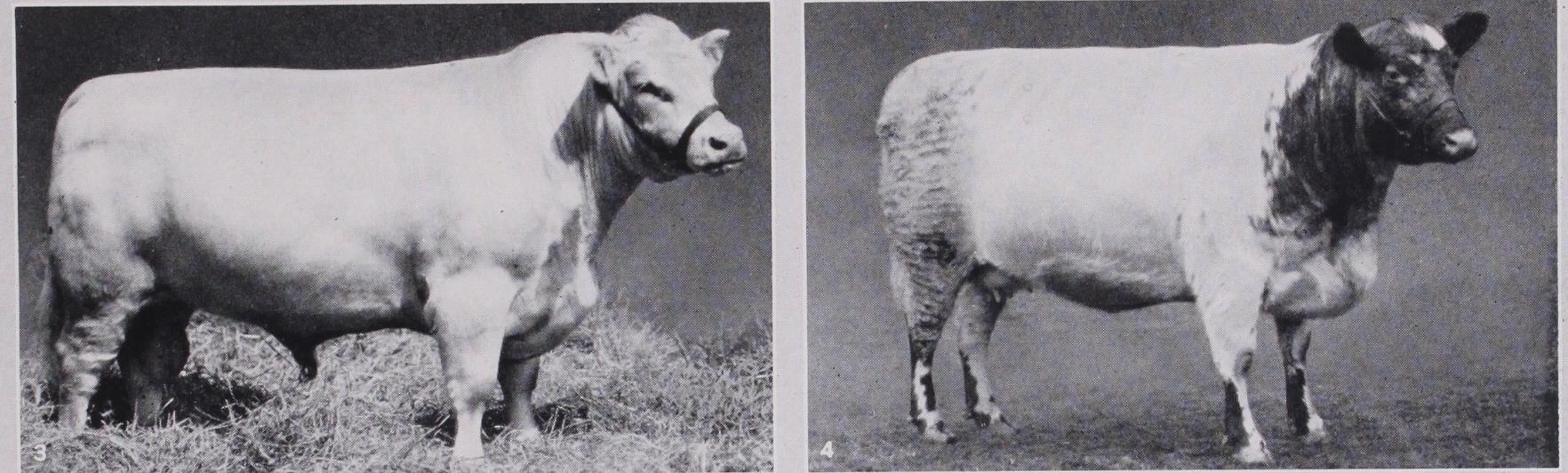

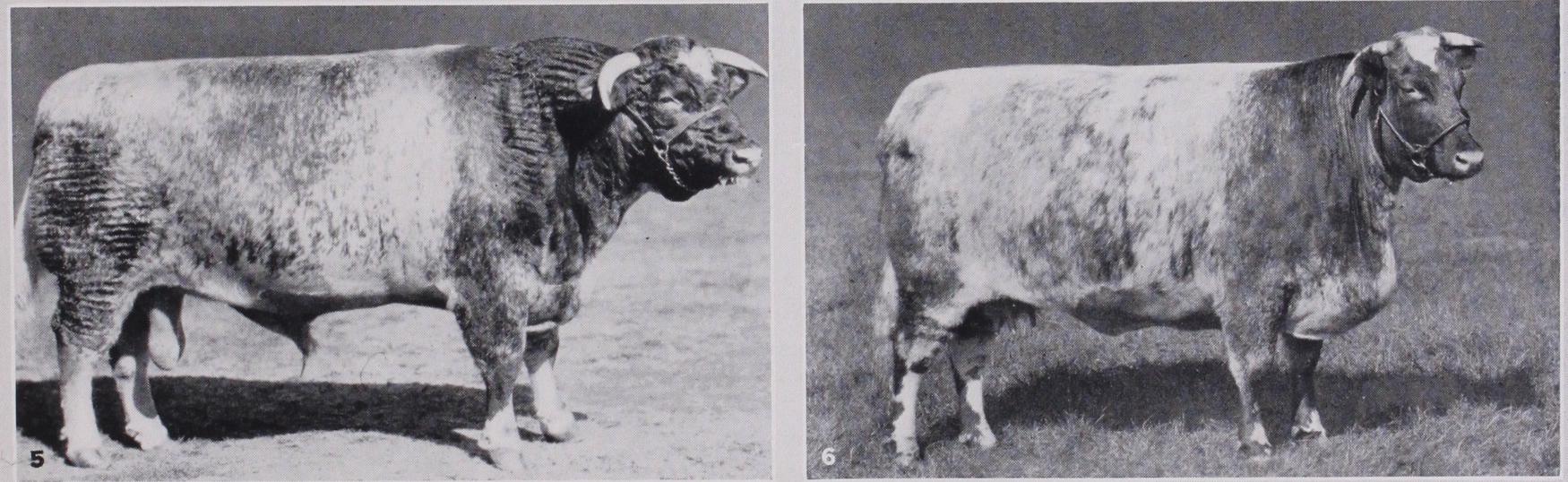

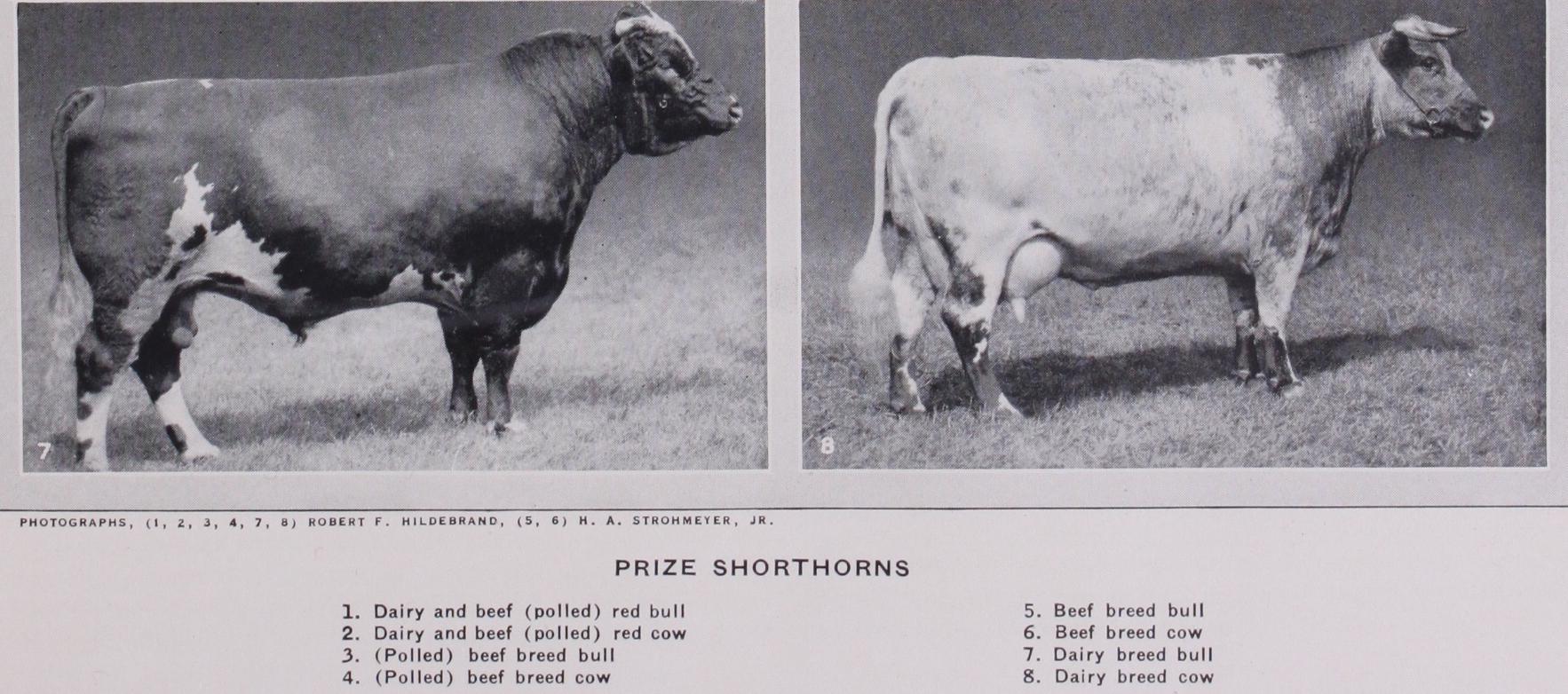

The Shorthorn.—The Shorthorn affords the most notable in stance of the "making" of a breed by a few enterprising and skil ful breeders. In the last quarter of the 18th century two brothers, Charles and Robert Colling, farming in Durham, started to im prove the local cattle of the Teeswater district of that county. From the place of its origin the Shorthorn is commonly known as the "Durham" in countries to which animals of the breed have been exported. By careful selection and breeding they gradually improved the type and their efforts were supplemented by other enlightened breeders, notably by Thomas Booth and Thomas Bates in Yorkshire. These two enterprising men each had his own conception of the precise lines on which the breed should be de veloped and for many years there was keen rivalry between those who preferred the "Bates strain" and those who favoured the "Booth strain." During the middle of the lgth century there was a Shorthorn "boom" which reached extravagant heights. The craze for particular strains and "families" led to excessive in breeding and the general excellence of the breed was endangered by insistence on "fancy" rather than on practical points. The cul mination of what may be termed the Bates and Booth period came in 1875 and thereafter there was a reaction from the tendency to rely on one or two "fashionable" strains, and a reversion to the more utilitarian principles of the founders of the breed. Breeders such as the Cruickshanks and later W. Duthie in Scotland and J. Deane Willis in England restored the constitutional vigour of the breed, which had been temporarily impaired by excessive in breeding.

The most distinctive characteristic of the breed is its adaptabil ity. It will thrive under diverse conditions of soil, climate and situation. A modern writer puts this forcibly: "To suit pasturage that is very productive a large beast can be secured; on the other hand medium, or even small cattle can always be produced from Shorthorns when required. In a harsh climate the breed can be relied upon to grow an abundance of soft, warm, weather-defying coat ; in more favoured climates this faculty is not brought into play. Given plenty of food to force growth, well-bred stock may be relied on for very early maturity ; on the other hand, when "done" only moderately well, the animal will gradually and slowly mature. No other breed can show such adaptability." Shorthorn bulls have also a high reputation for "prepotency," i.e., the faculty of impressing their qualities on their offspring. This is one reason why they are in such widespread demand for improving native stock in all parts of the world. Geographically, Shorthorns are more widely distributed than any other breed. To quote an American writer : "It is generally found in North America; in South America, more particularly in Argentina; in Europe, being the most prominent breed in the British Isles, although bred to some extent on the Continent ; in Australia, where it has long met with favour, and to some extent in South Africa and Asia. In the United States the Shorthorn is the most popular breed. However, on the western range, under severe winter conditions, and where "roughing it" is required, the Shorthorn will not thrive quite equal to the Hereford or Galloway." The Shorthorn Herd-book (the first of its kind) was started in 1822 by George Coates and was published as a private compilation until 1876 when it was taken over by the Shorthorn Society. The American Shorthorn Herd book was first published in 1846. The Canadian Shorthorn Herd book was started in 1867. Over 600,000 Shorthorns are registered in the United States and several thousands in Canada.

Dairy Shorthorns

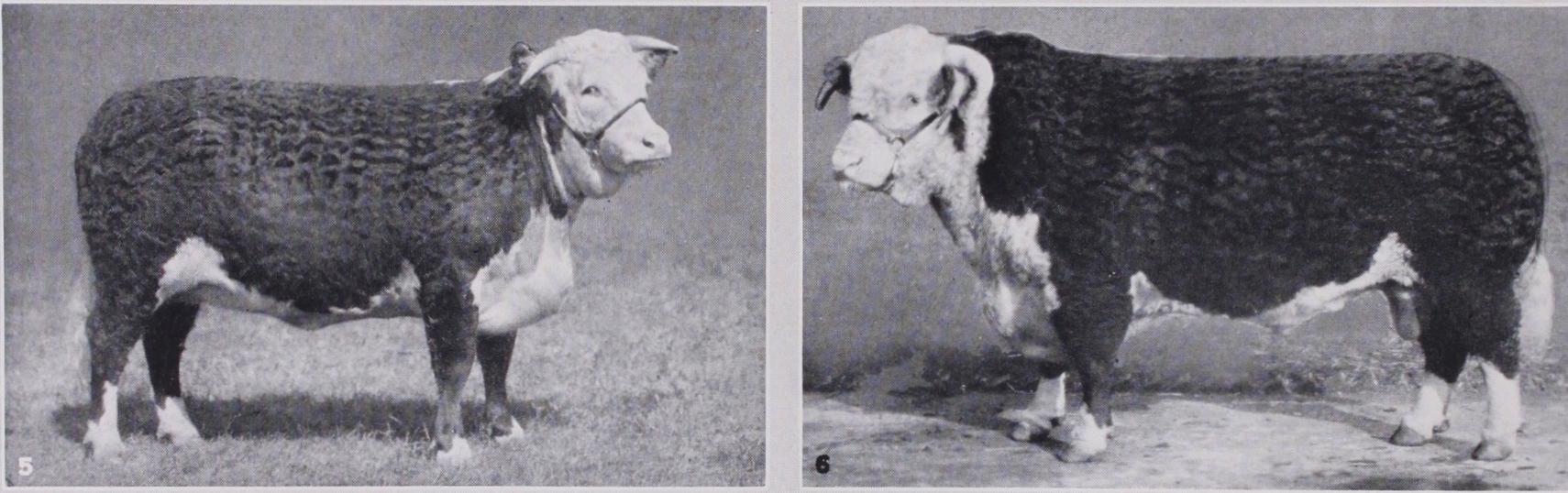

are an offshoot of the breed in which its milking qualities have been specially developed, and Lincolnshire Red Shorthorns are a specialised type of the original stock.The Hereford.—The temporary decadence of the Shorthorns referred to above, gave an opportunity to the Hereford breed to become established on the ranches of America. Its strong con stitution and thick coat of hair make it specially suited to stand exposure and to thrive under conditions of hardship.

The origin of the breed is obscure but there are good grounds for the claim that it is directly descended from the primitive cattle of the country. It still carries signs that it was for cen turies bred mainly for the plough, and even to-day, after several generations of improvement, a Hereford ox looks more suited for a plough team than any other English breed, with the exception of the Sussex. It is remarkable that its picturesque and very characteristic colour (red with white face and front) has only been fixed during the last half century or little more. When the first herd-book was published, in 1846, the editor grouped Here f ordshires in four classes, viz., mottle-faced, light grey, dark grey and red with white faces. Within the next 25 years all the colours but the last have practically disappeared. The modern development of the Herefords began earlier than that of the Shorthorns, having started with Richard Tompkins who died in 1723. The work was continued by his son and grandson and other breeders, among whom John Price and John Hewer were notable. Herefords were first introduced into America in 1817 by Henry Clay of Kentucky, but they made little progress until the '7os, when T. L. Miller of Illinois pushed them vigorously and successfully. He may indeed be regarded as the founder of the breed in the United States. It was introduced into Canada in 186o by F. W. Stone of Guelph.

The Sussex.—The Sussex breed is not only in direct descent from the original stock of the country but also has probably undergone little change in outward appearance since the middle ages. Its native home is the Weald and for centuries it supplied the working oxen in that district and other parts. Low, in his well-known book, writing in 1845, says: "The practice of em ploying oxen in the labour of the farm is universal in the county of Sussex, and the native breed is eminently suited to this pur pose, combining weight of body with a sufficient degree of mus cular activity." The use of oxen for farm work continued longer in Sussex, and particularly on the stiff clay of the Weald, than in any other part of the country and this was mainly attributable to the suitability of the native breed for the purpose. The colour of Sussex cattle is a uniform red. They have a good reputation as grazers, and their quality as butchers' beasts has been increased since they began to be systematically improved about the middle of the last century. Mr. A. Heasman published the first three volumes of a Sussex handbook in which pedigrees were given from 1855. In 1888 the Sussex Herd-book Society took over the publication and in the same year the American Sussex Cattle Association was formed. The distribution of the breed is some what restricted and even in England it is not widely kept outside its own county, but there are herds in the United States and Canada where it is successfully used for improving the grazing qualities of native stock.

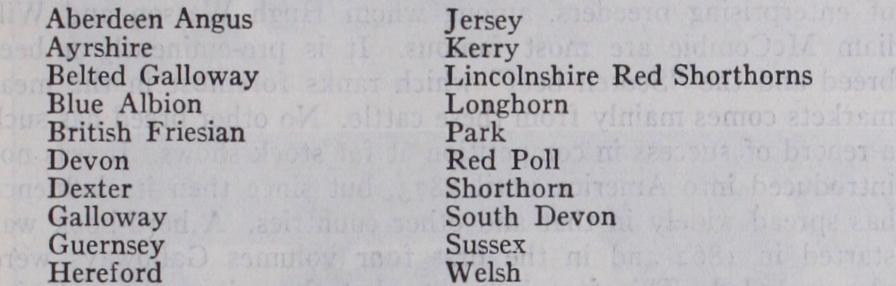

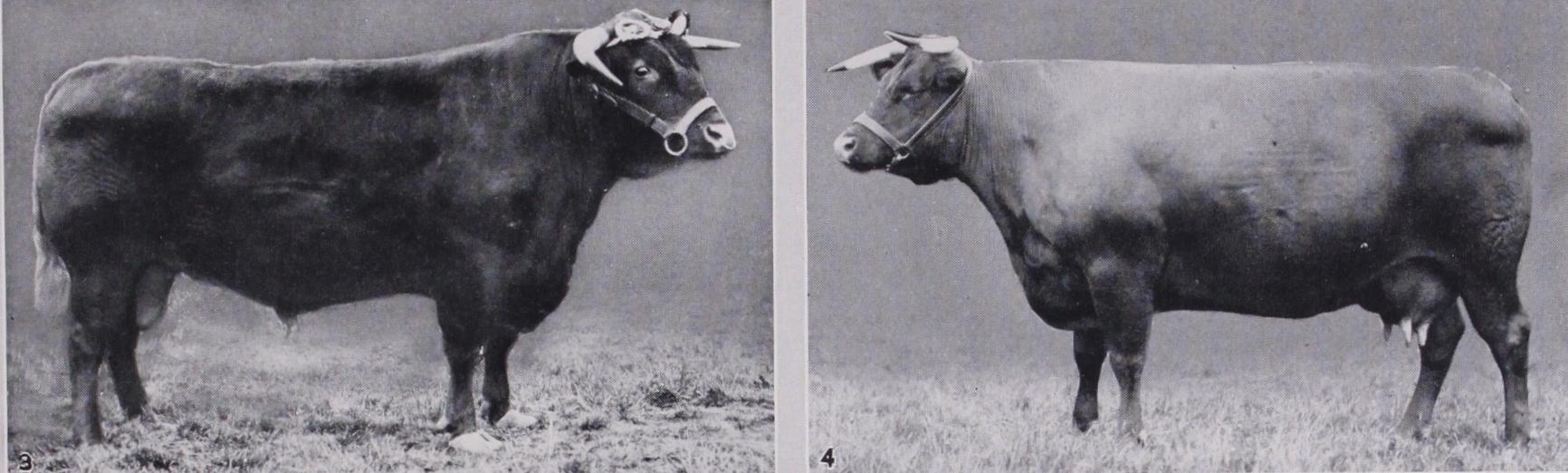

The Devon.

The Devon is another breed which can claim long descent, and cattle of this type were probably kept by the Britons who were driven to the west country by successive in vaders. Devon cattle much resemble Sussex cattle except in size and are probably descended from the same original stock. They are deep red in colour but much smaller and more active than the Sussex. Like them they were for centuries bred primarily for the plough, and the more hilly country and harder climate adapted them to their environment. Their neat, compact, symmetrical form and rich ruby colour make them perhaps the most attractive breed in the country. They produce beef which is claimed, not without justice, to be equal if not superior to that of any other breed, and the extension of the popular demand for small joints should bring them into still greater favour with graziers. Although not naturally heavy milkers the cows yield milk of especial rich ness. The improvement of the breed both for meat and milk was undertaken early in the last century by Francis Quartly, and it was stated about the middle of the century that nine-tenths of the herds then kept were "directly descended (especially in the early parentage) from the old Quartly stock." Francis Quartly is said to have been incited to preserve and develop the breed by the fact that "breeders generally, on account of high prices, were selling their best stock for slaughter and keeping poor cattle in reserve." His brothers, William and Henry, as well as John Tan ner Davy and his two sons continued the work. Davy's grand son not only possessed a famous herd but started the Herd-book in 1851 which was taken over by the Devon Cattle Breeders Society in 1884. It is stated by an American writer that Devons were probably the first "real pure-bred" cattle to reach America, "the vessel `Charity' which sailed in 1623 being thought to have had Devon cattle on board." However this may be it is on authen tic record that Coke of Holkham sent a present of a Devon bull and six heifers to Mr. Patterson of Baltimore which were the foundation stock of the American Devon Record. The breed is widely but sparsely distributed in America and in many other countries.The South Devon, or as it is sometimes called, the South Ham breed, bears little resemblance to the cattle of the north of the county. It is larger and less symmetrical in frame and of a lighter red in colour. The cattle are excellent for dairying purposes and the milk is not only plentiful but rich in quality. They are better adapted to the lower levels than to the hills, and their natural home is along the southern coast of West Somerset, Devon and East Cornwall. The cows of this breed mainly provide the milk from which is made the well-known Devonshire and Cornish cream. The South Devon Herd-book Society was established in 189o.

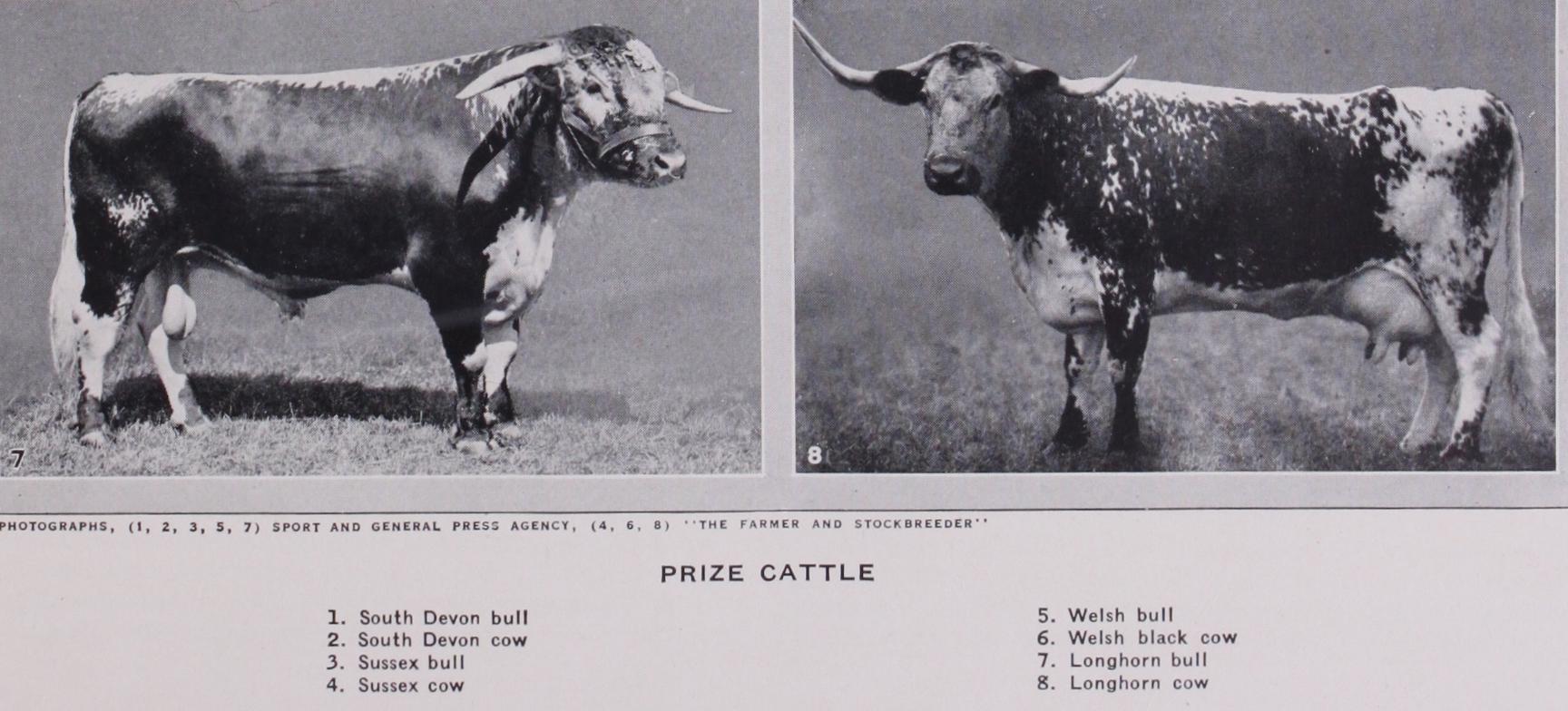

The Longhorns.

The Longhorns were at one time widely dis tributed in England and Ireland and were no doubt survivors of an ancient race. They were big, heavy and rather ungainly with long drooping horns which gave them their name. The Shorthorns displaced them in almost every district, but they are famous as the stock on which Robert Bakewell exercised his remarkable skill as a breeder in the latter half of the 18th century. But even his art did not succeed in restoring them to general favour and not many years after his death it was recorded that "on the very farm on which Mr. Bakewell's original experiments were instituted and completed, and within many miles around there does not exist a single bull, cow or steer of the breed which he cultivated with so much labour." The breed has lately been re vived and improved and there are now a number of herds in existence.

The Red Poll.

The Red Polls are an amalgamation of two breeds which had been common in Norfolk and Suffolk respec tively for centuries. The Suffolk cattle appear, so far as records exist, to have been always hornless, while those of Norfolk were horned but had the blood-red colour which is now typical of the amalgamated breed. The year 1846 has been fixed as the date when the Norfolk and Suffolk were merged, and for many years the breed was termed "Norfolk and Suffolk Red Polled." A herd-book was started by Mr. H. F. Euren in 1874 and in 1888 this was taken over by the Breed Society which was then formed, and the name "Red Poll" definitely adopted. It is claimed for the breed that they are "dual-purpose" in a greater degree than any other, that is that they are equally good as producers both of meat and milk. They are widely distributed at home and abroad but they are not kept in large numbers in any district except the two counties of their origin.

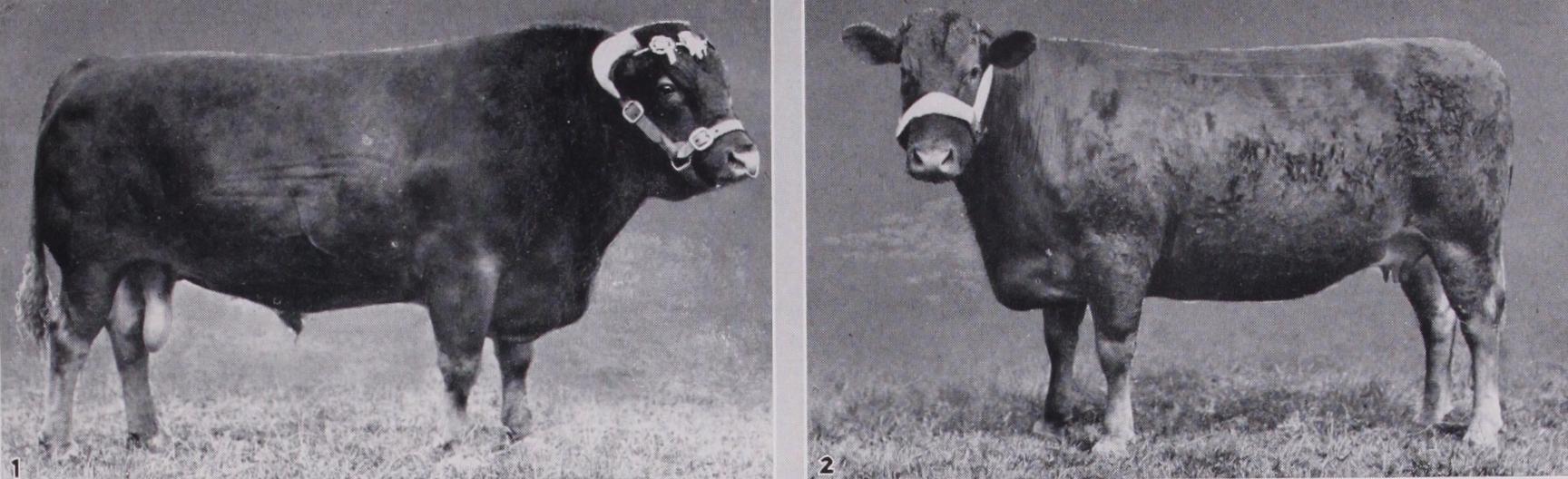

The Scottish Breeds.

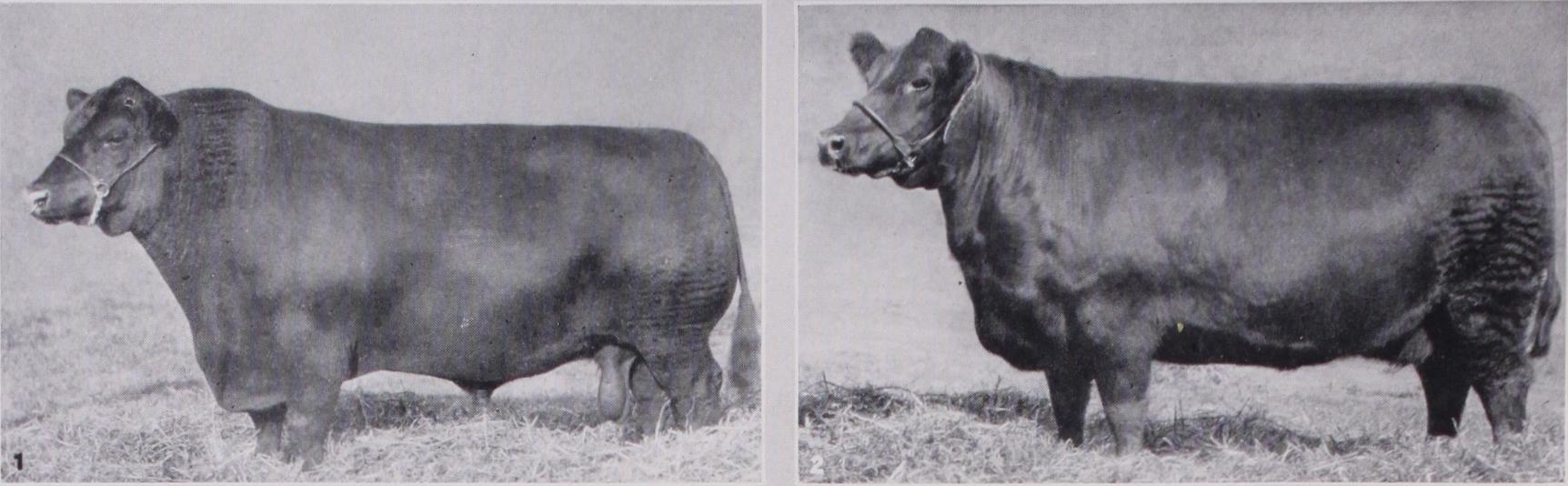

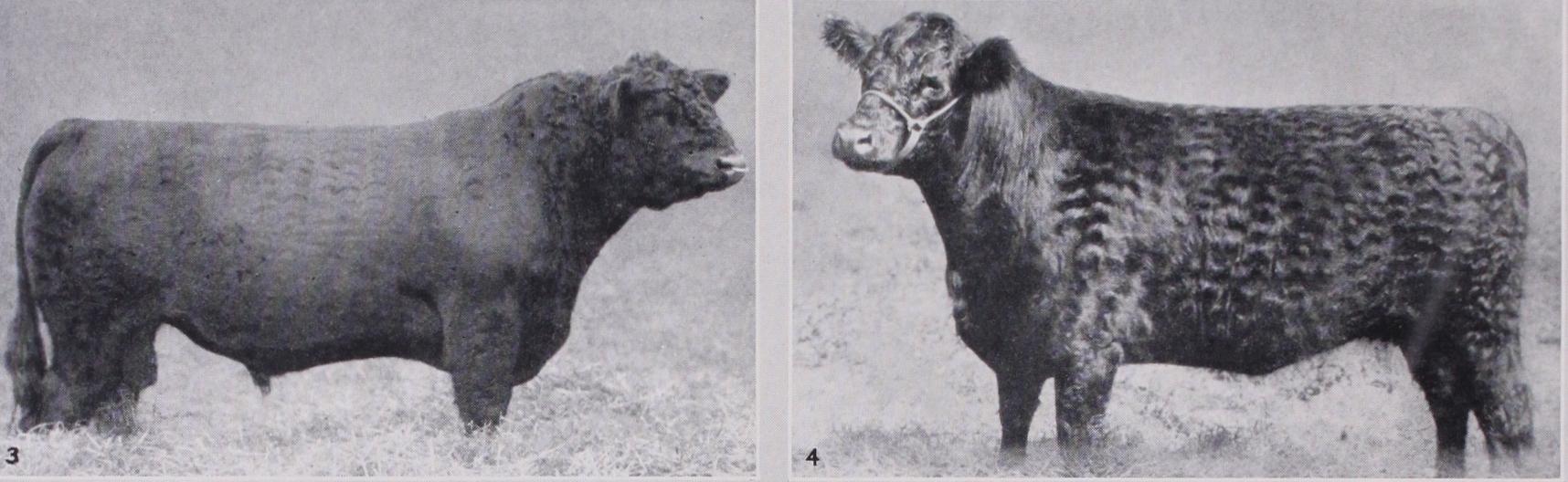

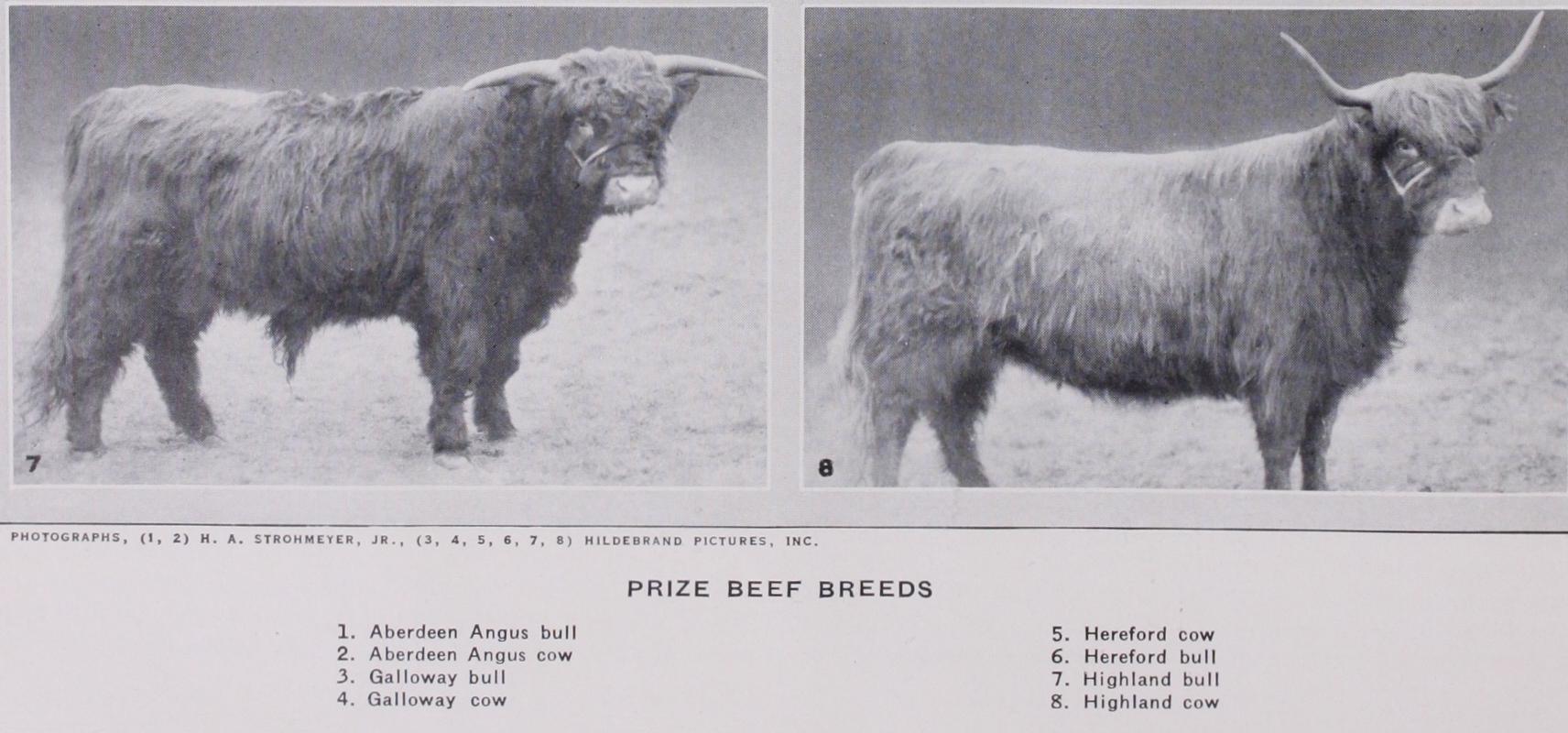

The Scottish breeds include the Aber deen Angus, the Ayrshire, the Galloway, and the Highland cattle. The Aberdeen Angus, commonly termed "Doddies," are a black polled breed. Their origin has been much discussed and it has been suggested that they sprang from a horned black breed which formerly existed in Scotland. Hornless or polled cattle have, however, been long known in that country. They were improved and their present type fixed early in the last century by a number of enterprising breeders, among whom Hugh Watson and Wil liam McCombie are most famous. It is pre-eminently a beef breed and the "Scotch beef" which ranks foremost in the meat markets comes mainly from these cattle. No other breed has such a record of success in competition at fat stock shows. It was not introduced into America until 1873, but since then its influence has spread widely in that and other countries. A herd-book was started in 1862 and in the first four volumes Galloways were also included. This fact indicates that there is a close affinity between Galloway and Aberdeen Angus cattle. The Galloway is a polled black breed and probably had a common origin although its native home is the ancient province or kingdom of Galloway in the south-west of Scotland. Its improvement was undertaken in the latter part of the 19th century by the Duke of Buccleuch and others and it now stands very high as a beef-making breed. It is almost more famous for its parentage of cross-bred cattle than for pure-bred animals. Galloway cows crossed with white Shorthorn bulls, which are bred for the purpose in that district, produce the "blue greys" which are more sought after by graziers than any other type of store cattle. The Galloway Cattle Society was formed in 1878 and published the first herd-book of the breed.The Highland or West Highland breed, sometimes termed "Kyloes," have their home in the Western uplands of Scotland. It is generally agreed that they are the aboriginal cattle of that district. Their long shaggy coat, sturdy frame, large head and branching horns, thick mane and heavy dewlap make them the most picturesque cattle in the British Isles. The colour varies but a tawny red is the most characteristic. They are very hardy, breeding and living all the year round on the hills, and thriving on scanty pasturage. They are slow in maturing but make beef of the highest quality.

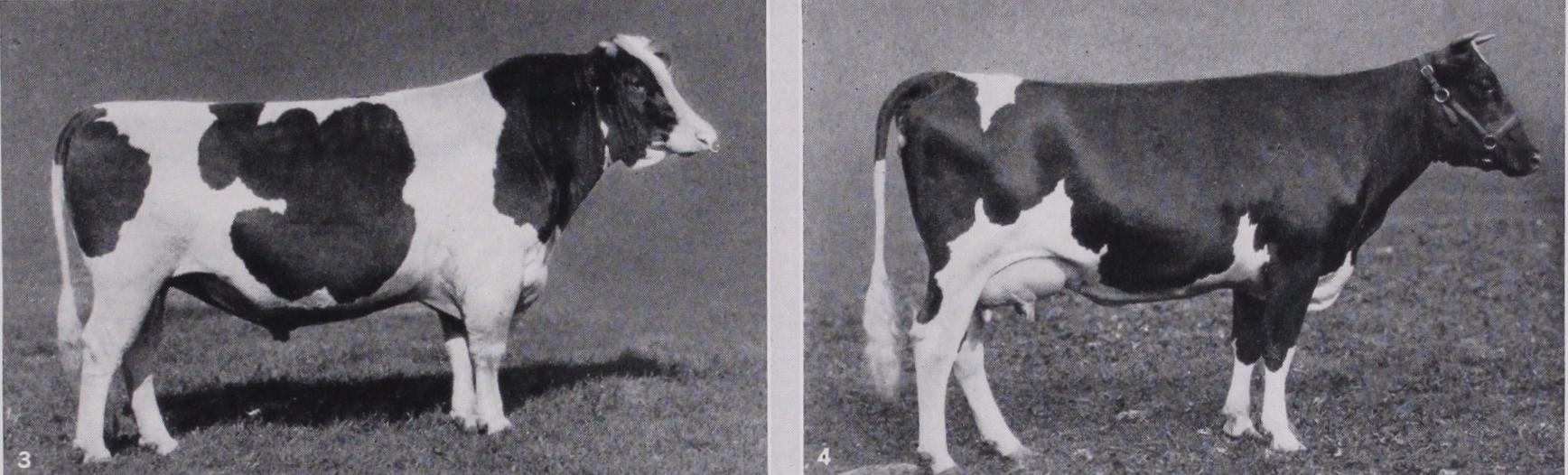

The Ayrshire is the dairy breed of Scotland. It is no doubt de rived from the native cattle of the county from whence it takes its name, but there seems to have been in the early part of the last century a considerable admixture of other breeds, including Shorthorn and according to some writers, Channel Islands cattle. The breed has been steadily developed for milk production and is now famous for the quantity of milk which the cows yield. The milk is largely used in making the cheese for which this part of Scotland is celebrated. The beef-making qualities of the breed are subservient to milk-production, but among the dairy breeds it takes a good position in this respect. The distribution of the Ayrshire is very wide. On the other side of the Atlantic it is most strongly represented in Canada, but it is also to be found on the Continent of Europe as well as in New Zealand. The Ayrshire Cattle and Herd-book Society was founded in 1877 and published the first volume of the herd-book in the following year.

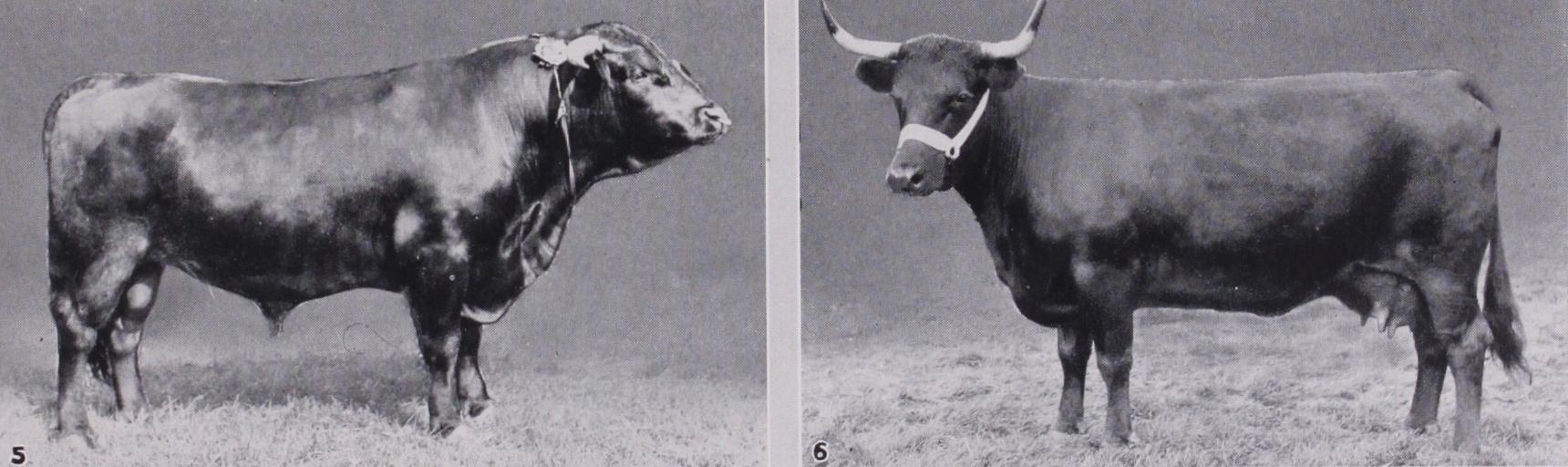

Welsh Cattle.

The Welsh breed is black with fairly long horns. Up to the beginning of the present century there were two types known as North and South Welsh respectively, but they were amalgamated in 1904 when the Welsh Black Cattle Society was formed and a common herd-book was established. The cattle mature a little slowly but grow to a large size and furnish beef of prime quality. Under the name of "Welsh runts" they are bought largely by English graziers in the midland counties.

Channel Island Breeds.

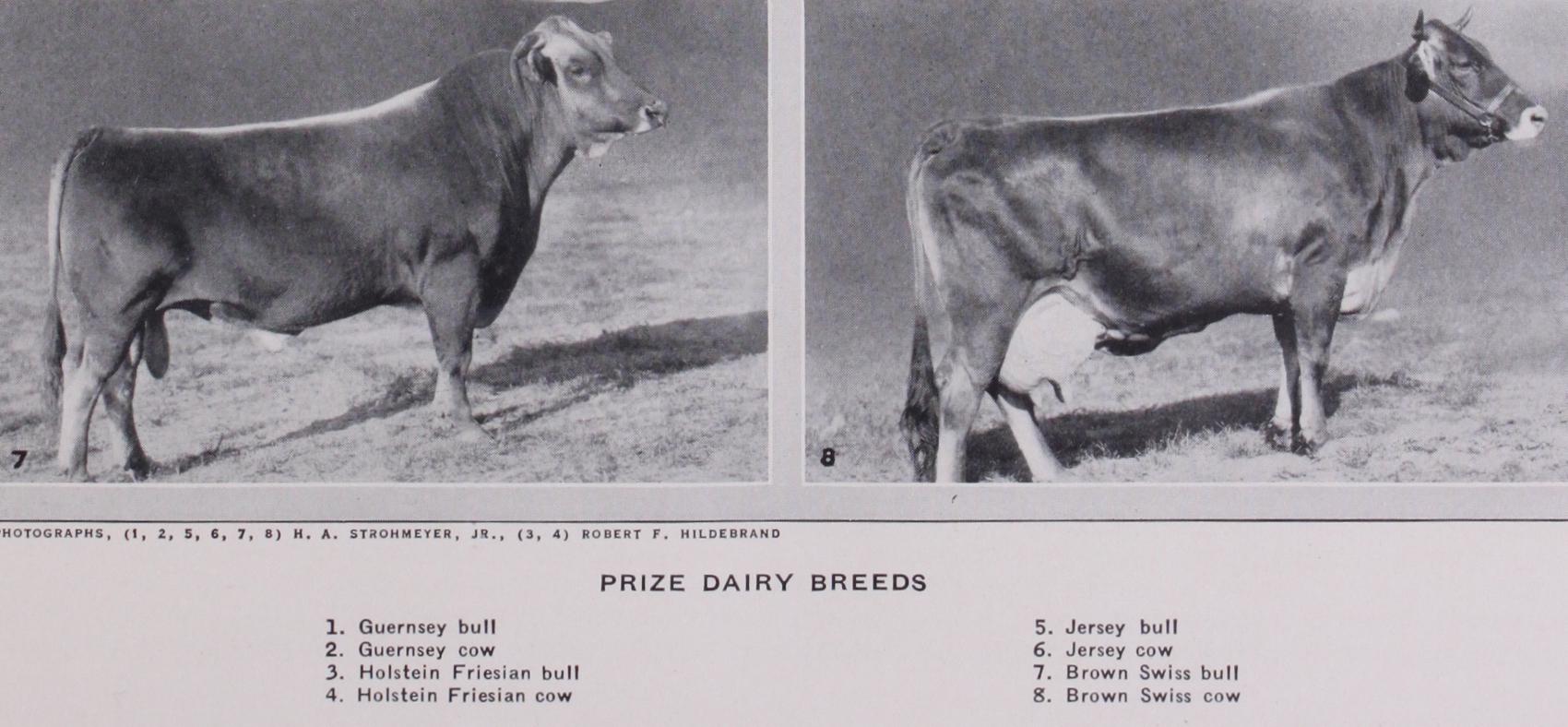

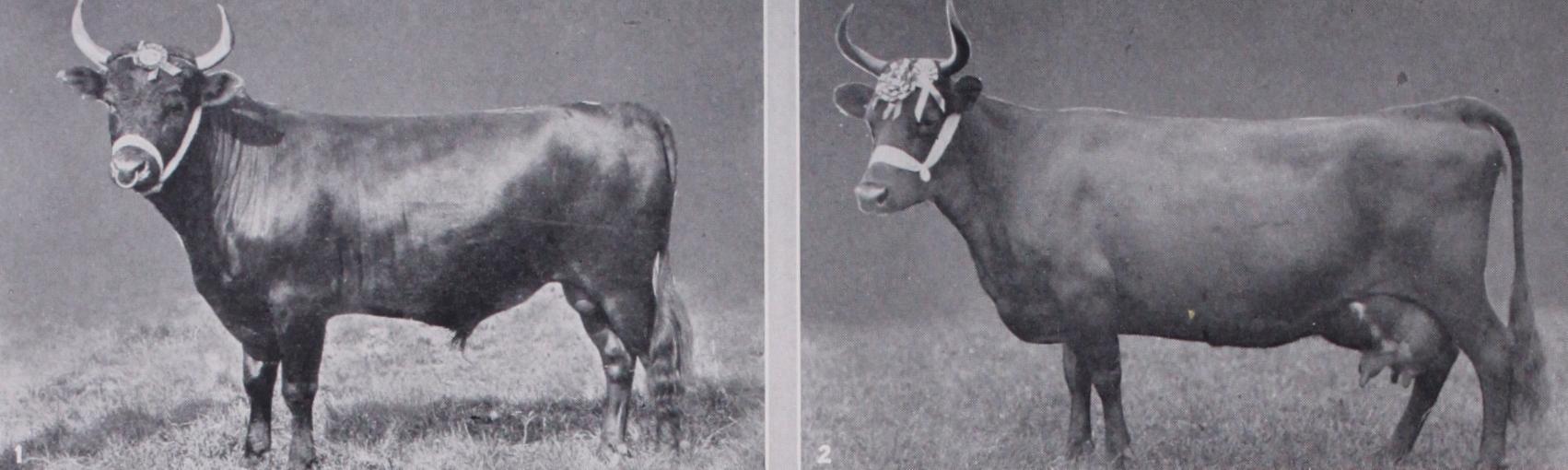

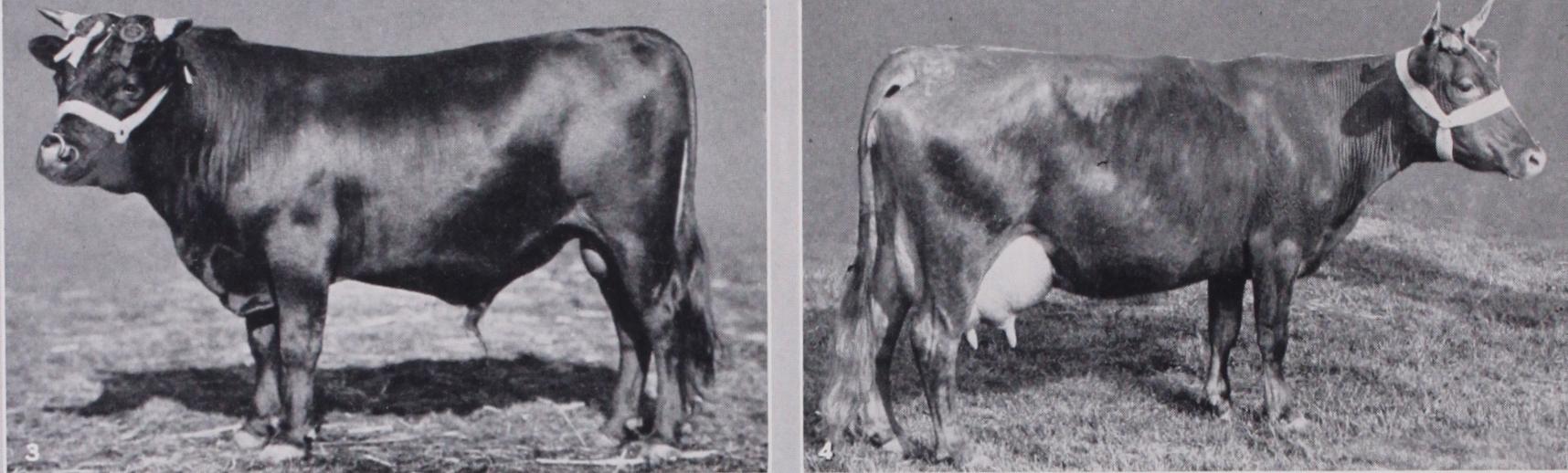

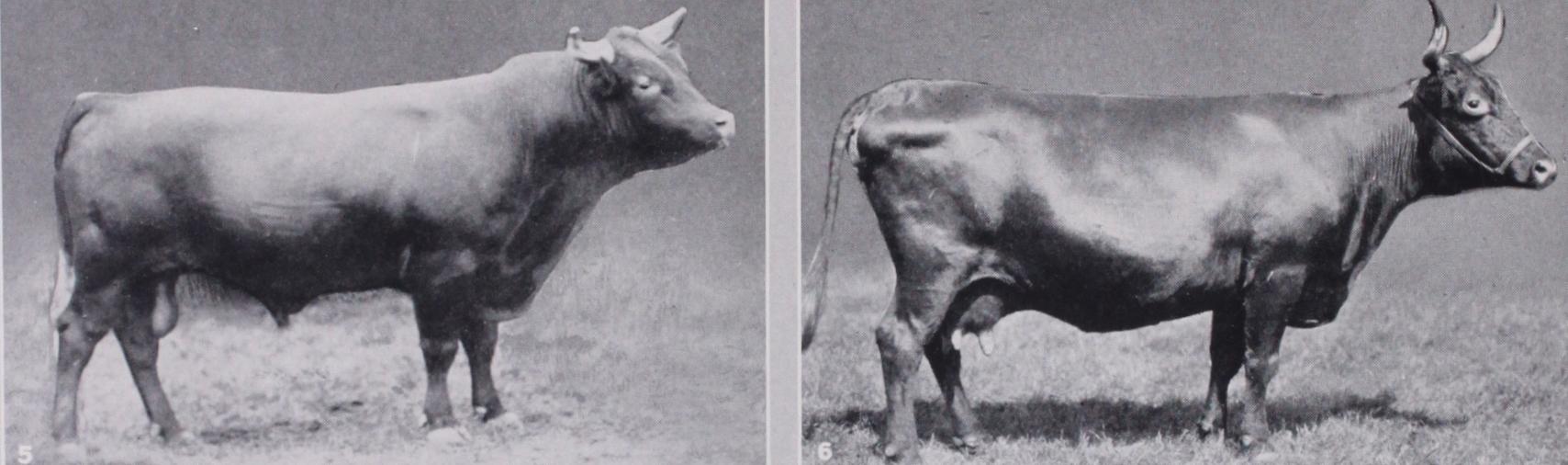

The Jerseys may have sprung from stock imported from Normandy and Brittany but they have been developed in their island home, and the purity of the breed has been secured by legislation dating as far back as 1763 prohibiting the importation of cattle. They have been introduced in large numbers into England, one of the earliest herds to be formed being that of Lord Braybrook in 1811. Not long afterwards a few were sent to the United States. They are now very widely kept. They are specially attractive in form and colour, and their "deer-like" appearance makes them popular for private parks. They yield milk which is remarkably rich in butter-fat and are therefore in demand for crossing with other breeds to improve the quality of the milk.

The Guernsey breed is of much the same type as the Jerseys but larger. Its merits for the dairy are practically equal. Cattle from the Channel Islands were long known as "Alderneys," a mistake which appears to have originated in a book on cattle which had a great vogue a century ago. There is no "Alderney" breed, the cattle kept on that island being Guernseys.

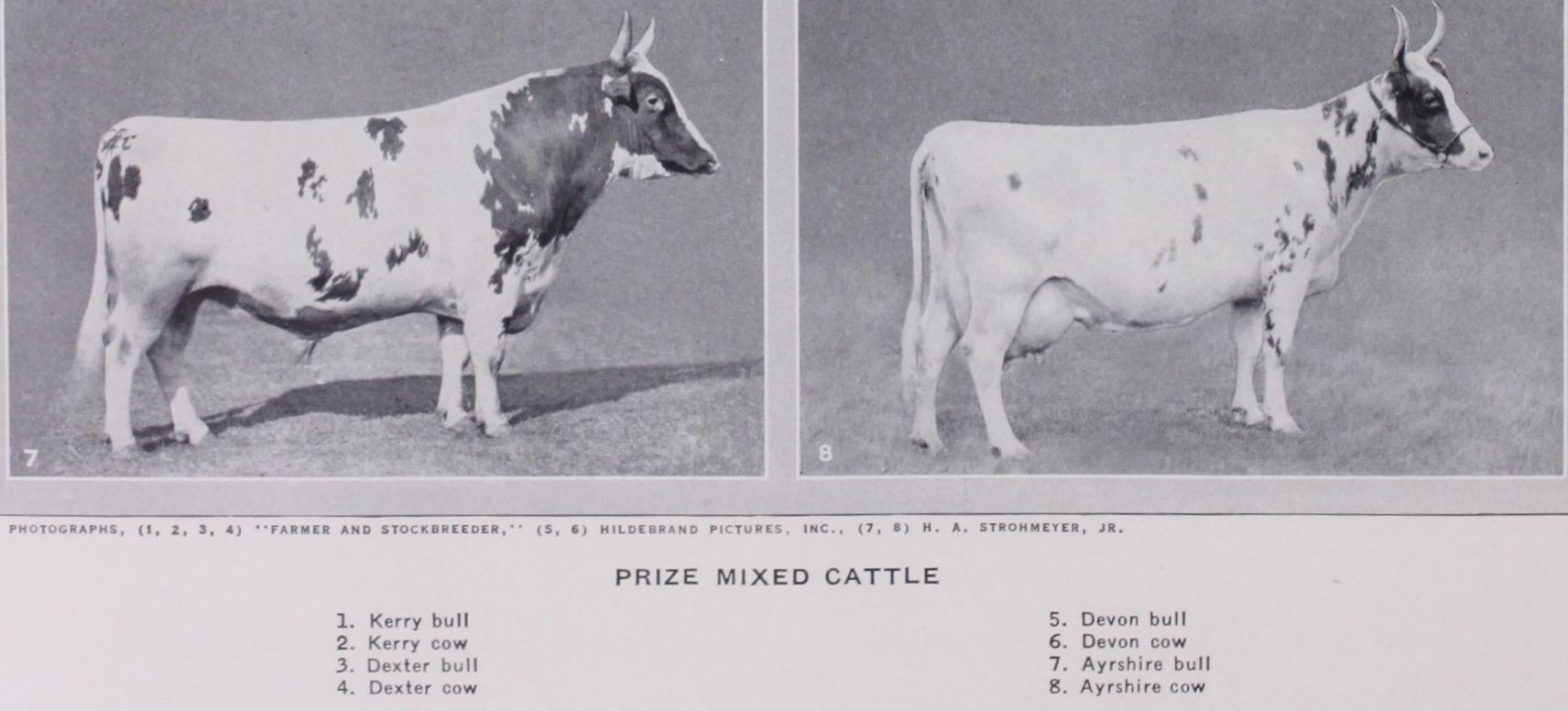

The Kerry and Dexter.

The Kerry is a breed of small black cattle in the south-west of Ireland from whence they have spread to all parts of that island as well as to England. They are very hardy and will thrive on the roughest fare. The cows are ex cellent milkers. An offshoot of the breed known as Dexters and at one time as Dexter-Kerries is said to have been established by selection and breeding from the best mountain type of the Kerry. They are smaller in size and are valuable as producers both of milk and meat.

Pedigree Cattle-breeding.

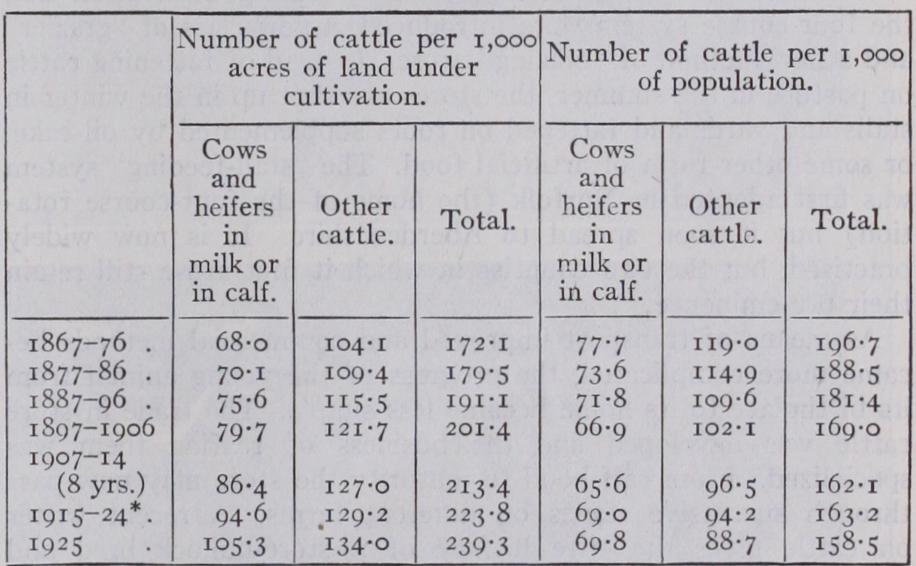

In the above notes on the prin cipal breeds reference has frequently been made to their present wide distribution. The exportation of breeding cattle from the British Isles began at an early period owing to the natural excel lence of the stock of the country. The general movement for the improvement of stock, of which Robert Bakewell was the most celebrated pioneer, but in which other enterprising breeders in various parts of the country participated in the latter half of the 18th century aroused the attention of agriculturists not only at home but abroad. Bakewell kept open house with rustic simplicity for all who came to see his stock. "In his kitchen," says the his torian of English farming, Lord Ernle, "he entertained Russian princes, French and German royal dukes, British peers and sight seers of every degree." At the "Holkham sheep-shearings" Mr. Thomas Coke entertained visitors on a princely scale. "Hun dreds of persons," says the same writer, "assembled from all parts of Great Britain, the Continent and America," and these annual gatherings were described in the "Farmers' Magazine" as "the happy resort of the most distinguished patrons and ama teurs of Georgic employments." The fame and merits of British live stock as the source from whence the finest cattle could be obtained became wide spread, and the enterprise of breeders was also displayed in finding markets for them. The expansion of the United States created a demand for cattle of superior type to form the foundation of new herds or to improve and develop the native "scrub" animals. It was recognised that cattle which had been long bred true to type, in other words "pedigree" cattle, could be relied on to impress their character on nondescript animals. The building up of a breed, as practically all the existing breeds have been built up, was a process of selection and elimina tion. The breeders who undertook this work came gradually to agreement as to the exact type to be fixed. In this the various live stock shows, notably those of the Royal Agricultural Society, the Highland and Agricultural Society of Scotland and a number of county and district societies throughout the country (see AGRICULTURAL SHOWS AND SOCIETIES), greatly assisted. By competition and comparison, owners of different herds were able to arrive at general uniformity and the "points" of a pure-bred animal of a particular breed were formulated in an accepted standard. The establishment and maintenance of a pedigree herd were undertaken by a limited number of breeders. Unlike ordinary stock-owners the main object of these men was not to supply cattle to the grazier or butcher, but to sell the animals solely for breeding purposes. The greater number of cattle kept by ordinary farmers are not pure-bred and to keep up the quality of their herds bulls and cows are from time to time purchased from the pedigree breeders. But the home market was for many years subsidiary to the oversea market. Thousands of cattle have been sold, often at very high prices, to oversea buyers and during the last century the trade in pedigree stock was very remunera tive. In course of time the demand naturally decreased. In the countries to which pedigree cattle were sent herds were gradually established which in a few years had attained a level of excel lence equal to that of the parent stock. Thus the United States which for many years imported large numbers of pedigree stock from Great Britain has now become independent of the original source, and in the same way Canada, Australia and New Zealand are now much less regular customers. Argentina, where the im provement of the native stock came later, has in recent years been the chief buyer. On the basis of returns collected in 1921 by the Ministry of Agriculture from members of the various breed societies it was estimated that the number of "pedigree" cattle in England and Wales was 150,00o. As the total number of cattle in that year was 51 millions it will be seen that the overwhelming majority of the herds are "cross-bred." In many of these cases a pedigree bull is kept but the cows are of a mixed type. Distribution of Cattle.—The report on the agricultural output of England and Wales (see AGRICULTURE, CENSUS OF) contains some interesting statistics of the growth in numbers and present distribution of cattle. The following table shows the number of cattle at successive periods in relation to the agricultural area and the population of the country:— *In the years 1915 to 1920 inclusive the population figures excluded non-civilians.

The density of the cattle population varies greatly. In England and Wales as a whole there are, as shown above, 239 cattle per I ,000 acres of agricultural land of which 105 are cows and heifers in milk or in calf and 134 other stock. Wales is more heavily stocked than England, the comparative figures being:— The county which is most densely stocked is Anglesey with 383 head, and the most sparsely stocked is west Suffolk with 89. Cheshire stands first for cows and heifers with 249 and west Suf folk lowest with 32. With other stock Anglesey takes the lead having 266 head per i,000 acres and west Suffolk again lowest with 57.

The Cattle Trade.

The number of cattle exported from Great Britain "for breeding," i.e., pedigree stock, was 6,5o1 in 1926 and 6,827 in 1925. Among cattle exported "for food," the British trade accounts now show those sent to the Irish Free State. The number was 10,411 in 1926 and 12,991 in 1925.The number of cattle imported into Great Britain for food was 708,868 in 1926 and 800,144 in 1925. Of these the Irish Free State sent 628,918 in 1926 and 688,12o in 1925. Practically all the remainder came from Canada. The cattle brought into Great Britain from Ireland and a large proportion of those from Can ada are "stores," that is young stock in a more or less lean con dition which have to be kept and fattened for slaughter. The breeding and fattening of cattle are two distinct businesses carried on in the main by separate individuals. One farmer devotes himself to the breeding and another, probably in a different and distinct district, to the fattening. This division of functions arises out of natural conditions. In many parts of the country, particu larly in the west Midland counties and in Wales, the natural pasturage is plentiful but generally poor, but it is well adapted to the breeding of cattle and much of the country being hilly the conditions are healthy, and tend to develop vigorous and hardy young stock. In the Midlands and in one or two other districts there are some of the finest natural pastures in the world on which cattle can be fattened even without artificial food. From these circumstances there developed in very early times a regular trade. Dealers would collect from various farms a number of young store cattle and drive them to the fattening districts, selling them there either directly or at the local markets to the graziers. This was a regular trade not only long before the advent of rail ways but before roads were generally made. The cattle were driven, as we should say, "across country" on the waste land and commons which then spread over so large an area and their regu lar tracks or "droveways" may be traced to this day. Similar droveways were also made by herds of fat cattle sent to the Lon don market from as far distant as Scotland.

As modern farming, and particularly turnip cultivation and the four-course system were introduced, a new class of "grazier" and a new method of "grazing" arose. Instead of fattening cattle on pasture in the summer, the stores are shut up in the winter in stalls and yards and fattened on roots supplemented by oil-cake, or some other form of artificial food. The "stall-feeding" system was first adopted in Norfolk (the home of the four-course rota tion) but it soon spread to Aberdeenshire. It is now widely practised, but the two counties in which it first arose still retain their pre-eminence.

As means of transport improved and commercial methods be came more complicated, the progress of the young animal from its birthplace to its home became less simple. The trade in store cattle was developed and the business of rearing them was specialized. From calf-hood to maturity the store may now pass through successive stages on different farms. A recent writer on cattle gives the "life history of a store-bullock bred and reared on pasture" as follows:— Situation Age On a breeding farm Birth to Medium "store-land" 6 months Medium " " 7-12 " Medium " " . . . . . . . . 13-16 " i3-16 On a store-rearing farm 17-24 Good store-land . . . . . 24-30 " Good " " . . . . . . 31-36 " After this he goes to another farm for the finishing process. This may be regarded as an extreme case, but it fairly indicates the complexity of the store-cattle trade. At the other extreme there is the case, not uncommon and tending to become more popular, of the breeder who rears and fattens his own stores on his own farm.

The cattle dealer as an intermediary between the breeder and the feeder and the feeder and the butcher has played a large part in the organization of the trade in both store and fat stock. But within the last half-century he has been to a large extent elimi nated by the auctioneer. Not only at the ancient cattle markets but in numerous "auction marts" which have sprung up all over the country, sale by auction has supplanted the old methods of sale through intermediaries and also of direct dealing between farmers and butchers.

BIBLIOGRAPHY.-The

Complete Grazier, by a Lincolnshire grazier Bibliography.-The Complete Grazier, by a Lincolnshire grazier (1st ed. 18o5, several later eds. extended and revised by different writers) ; Domesticated Animals of the British Islands, by David Low (1845) ; Farm Live Stock of Great Britain, by R. Wallace (19o7) ; Types and Breeds of Farm Animals, by Charles S. Plumb (Ginn and Co., 1906) ; Cattle and the Future of Beef-production in England, by K. J. J. Mackenzie, with a preface and chapter by F. H. A. Marshall (Camb. Univ. Press, 1919) . These deal comprehensively with cattle generally. Of some of the principal breeds, such as the Shorthorns, Devons, etc., the of each breed contains an account of its history and characteristics. (R. H. R.) The vastness and varied topography of the United States make not only possible but necessary a cattle-breeding industry very different from that of Great Britain. Instead of the diversified and intensive farming, general in Great Britain, great areas in the United States are devoted to special crops, as in the corn belt of the Middle Western States, the wheat belt of the Red river valley and Kansas, the cotton belt of the South. The most diversified farming is in the North-eastern States. Live stock farming co ordinates with the crop system ; the location of the different phases of cattle breeding is as varied as the culture of the crops.

Cattle Feeding.

The line between beef-making and dairying is more closely drawn in the United States than in Great Britain. American live stock operations are more specialized. One is either a beef maker or a dairyman, and this distinction was formerly characteristic of whole districts. The leading dairy States are still exclusively so, although interest and operation in beef cattle is expanding in the East. On the other hand, the corn belt States, formerly almost exclusively devoted to cattle feeding, now rank high in dairy industry. The bulk of the milk supply of the United States is derived from cows of dairy breeding, while most beef bred cows suckle calves and are not hand milked. But the beef and milk combination is becoming more popular as farm labour problems grow more complex in the dairy sections, and as land values increase in the beef breeding districts. Generally speaking, dairying dominates in the East, with many cities and large indus trial centres, although Wisconsin, Minnesota and Iowa rank first, third and fourth, respectively, among the dairying states, while Iowa also ranks first in beef production. Feeding cattle for beef is most important in the corn belt States, but a majority of the cattle fed there are bred on the far Western ranges. This fact is responsible for one of the most important divisions of the live stock industry—cattle ranching on a large scale, as in the Pad Handle district of Texas and New Mexico, the Sand Hills of Nebraska, the North Park of Colorado and in Montana, Wyoming, Idaho and the Dakotas.The life cycle of a beef steer takes him from the Western range, where he is bred and reared till weaned, to the Mid-Western feed lots (enclosures with corn and hay racks), where he is fed for market, thence to a great packing centre like Chicago, where he is made into a carcass of beef, to be transported in refrigerator cars to Eastern cities, where most of the best beef is consumed. The cattle range, which constitutes the chief source of the feeder cattle supply, is an American institution, although duplicated in Australia and Argentina. Grade cow herds, numbering several hundred, are grazed on Government or private lands, io to 4o ac. per head, depending upon rainfall and forest. Under favourable conditions one ton of hay and 4o ac. of grass will support a cow. Pure bred bulls are run with the cows, one mature bull to 20 or 3o cows. Many ranges maintain pure bred herds to furnish their own bulls. Others buy by the carload from the pure bred herds of the central States. Most calves are born in April and rounded up in July to be castrated, branded and usually dehorned, and, with the modern demand for feeder calves to make baby beef, many heifers, as well as steers, are shipped to feed lots in the fall. The ruling demand is for baby beef, and heavy cattle are usually penal ized on the market, although the highest price for 1926-27 was paid for heavy steers. But the demand is very limited for sound economic reasons. The American family is smaller than in previous times, beef is more costly, hence smaller cuts from lighter cattle are bought. Therefore the packer prefers goo to i,000-lb. cattle. The feeder, on the other hand, finds calves much more productive per unit of feed consumed than yearlings or two-year-olds, thus rivaling hogs. Breeders find the cost of wintering calves kept for stock out of proportion to the selling price of the yearling feeders; furthermore, heifer calves are taken almost as readily and at only slightly lower prices than steer calves, not suffering the discrimination made against yearling heifers. Baby beef best serves the interests of all concerned.

Dairying.

Dairying is so highly specialized that distinction is made between the breeder of pure bred dairy cattle, in whose case milk constitutes only a by-product, and the dairy operator, who keeps a bull merely to have fresh cows and does not raise his own replacements. Grade dairy cows, soon due to freshen—springers, as they are called in the trade—are purchased by the car load in the Middle West, and are shipped into the Eastern States to stock the large dairies near the cities. Many of these cows are not re-bred, but are fattened and slaughtered when their period of profitable lactation is completed. Other dairymen kill the calves at birth; these owners are concerned only with the fresh cow, nondescript bulls serving this purpose. Many 'dairy operators, recognizing the difficulty of securing good cows, and the importance of excluding tuberculosis and abortion disease infection, are raising the heifers from their best cows, sired by pure bred bulls. This results in high-grade cows of improved productive capacity.

Importations.

The United States has evolved three or four breeds of hogs, one of sheep and two of horses, but has originated no breed of cattle. But American breeders have made important contributions to the improvement of foreign breeds. The fact of importation has no value in Hereford and Holstein cattle. There have been but two notable importations of Herefords in nearly 25 years, and neither of these bulls is held to strengthen a pedigree. It is still longer since any Holsteins were imported, and records of performance of American Holsteins surpass those made by the cattle of Holland. The Shorthorn breeder highly values the im ported cow, and imported bulls usually out-sell American bred bulls. Aberdeen-Angus cattle, chiefly bulls, are imported in less numbers than Shorthorns. Certain American firms import Jerseys and Guernseys, both bulls and cows, while some American breeders buy in the Channel Islands. The St. Lambert Jerseys, which, as a family, originated in the United States, are still in favour to some extent on account of their high production, but in price range and show ring preferment, the Island type leads. Ayrshires of both sexes are imported, and the old New England type of Ayrshire has completely given way to the foreign type.

Distribution.

Shorthorns are the most widely distributed and generally useful of the beef breeds. They are in most States in which cattle are bred. Their grades are frequently found on the ranges of the North-west, and the feed lots of the corn belt, and Shorthorn bulls are used more than any other beef bulls to grade up common herds and to sire good veal calves from milking cows. Only pure Scotch cattle are in demand, except in some sec tions of the East, where good herds of milking Shorthorns have been established. The Polled Shorthorn, an American develop ment, has been much improved, and some of the best Scotch breeding is now found in the pedigrees of these cattle. Herefords, usually red with white face, have increased in popularity. They dominate the ranches, 90% of the ranch cattle being white faced, and they consequently dominate the feed lots. The prevalence of white faced cattle in the feeding districts is somewhat misleading as to breed preference on the part of the feeders. Most cattle feeding operations involve from a carload to 15 or more head, and uniform age, eblour and finish are required. It is impossible to se cure, except from the big ranches, as large a number of uniform cattle as required by most feeders. Since Herefords have proved best adapted to ranch conditions, these ranch bred feeders will generally be white faced. Ranchmen claim that the best herds of white faced ranch cattle have some Shorthorn blood, and they in troduce a Shorthorn cross occasionally to maintain size. Herefords are conspicuous at the shows, sometimes outnumbering the Short horns. Polled Herefords, evolved from pure bred stock, as in the case of the Polled Shorthorns, are bred to a considerable degree of excellence, and are preferred to the horned cattle in some regions.Aberdeen-Angus cattle are not so numerous in America as either Shorthorns or Herefords, but have a higher show record. At the International Live Stock Exposition at Chicago, they have won 14 of 25 single steer grand championships, 17 of 23 steer group grand championships, 21 of 25 fat carload grand championships, 24 of 25 carcass grand championships, and more than 7o% of the total awards in the carcass contest. Galloway cattle have found some favour on the North-west ranches and in Alaska, where they were introduced by the U.S. Government primarily for milk production. There are few pure bred herds. There are few herds of Devons, and of Sussex practically none. West Highland cattle are rarely seen except in parks. Holstein-Friesians are most numerous in the three leading dairy States, and all dairy districts where general market milk is the rule. They hold all records for milk production and have gained more honours for butter fat than any other breed. Guernseys lead in the Grade A milk field. Their promoters are featuring "Golden Guernsey" milk as a special product in effective propaganda. Jerseys were the original butter cows in the United States and are still preferred in many sections, especially the South. Ayrshire bulls have been used less than bulls of any other dairy breed for grading up, but the number of pure bred herds shows substantial increase. Red Poll cattle are in competition with milking Shorthorns as dual purpose cattle, but show little gain in number of herds and merit.

Registration.

American associations are maintained for the registration of cattle, and eligibility is based largely on the rules that govern in the older countries. A notable exception is found in the case of Shorthorns, which are not admitted under a top cross rule as in Great Britain. Red and White Holsteins are also ineligible. Further, there is no system of selective registration of Jerseys as on the Island of Jersey.

BIBLIOGRAPHY.--C.

S. Plumb, Types and Breeds of Farm Animals, Bibliography.--C. S. Plumb, Types and Breeds of Farm Animals, rev. ed. (192o) ; V. A. Rice, The Breeding and Improvement of Farm Animals (1926) ; C. H. Eckles, Dairy Cattle and Milk Production, rev. ed. (1923) ; R. R. Snapp, Beef Cattle—Their Feeding and Manage ment in the Corn Belt States (5925); A. H. Sanders, Shorthorn Cattle 1918) ; A. H. Sanders, The Story of the Hereford (1914) ; E. L. Potter, editor, Western Live Stock Management (1917).(C. W. GA.)