Cellulose

CELLULOSE. The main ingredient of the membranous cell walls of plants, which in the more advanced stages of develop ment assume elongated shapes and become tubular and fibrous. In the plant structure cellulose is always accompanied by other substances in intimate association, as incrustants, from which it can be freed by various methods. Cellulose of high purity is easily prepared from cotton, the seed hair of gossypium, by pro longed boiling of the raw material with 1% solution of sodium hydroxide, subsequent treatment with dilute acetic acid and re peated washing with distilled water : its analysis will then be about of cellulose and 0.05% of ash. Cellulose obtained in this sort of way is regarded as standard cellulose. Chemical filter pa per is practically pure cellulose, especially when it has received an exhaustive treatment with hydrochloric and hydrofluoric acids for removal of ash, which is partly siliceous. Standard cotton cellu lose is white, fibrous and of characteristic form and appearance: other pure fibrous celluloses, e.g., bleached flax, hemp, ramie, wood-cellulose, are equally characterized in form and appearance. Commonly it absorbs 6-8% of moisture in contact with the air, which is given off again by drying at i oo-105 ° C.: it appears that it gives up water more slowly than it absorbs it. When dry, cellu lose is a good electrical insulator with specific inductive capacity about 7. The specific gravity of cellulose is about 1.58 and de pends on its source and on its state or condition (woods, contain ing 4o-8o% of air, have an apparent specific gravity about 0.3 1.3) . W. N. Hartley (1893) and S. Judd Lewis (1918-24) have shown that cellulose is strongly fluorescent to much of the ultra violet spectrum; it appears that constituent groups within the cellulose molecule affect the fluorescent properties, as indicated by distortion of the characteristic frequency curve, so that it may be possible, eventually, to use this method in the determination of questions of constitution.

The properties of cellulose depend to a considerable extent on its state or condition. Thus, whereas cotton cellulose will absorb about 7% of moisture from the air, regenerated cellulose, such as artificial silk, will absorb similarly about io% and so on ; the gen eral experience being that almost any sort of pre-treatment tends to make some portion at least of the cellulose more reactive, and this effect is not reversible.

Comparison of Celluloses.

From cellulosic raw materials, celluloses can be separated by a variety of methods, some of which are of great industrial importance. The celluloses thus separated have properties that are not identical with those of standard cotton cellulose. The cotton cellulose is, for example, relatively more resistant to the action of acids (hydrolysis) and alkalis than are other celluloses. The less resistant portions of the celluloses are termed hemicelluloses. Whether or not the more resistant, less soluble residual portions of these celluloses are identical with the resistant cellulose of cotton is a difficult ques tion, not yet finally answered, on which recent methods of in vestigation by X-ray analysis have given valuable information. Something of the nature of the difficulties underlying this kind of enquiry will be appreciated from the following considerations. Classical chemistry has achieved its successes largely by analytic and synthetic methods of re-arranging atoms and molecules in fluid media (gases, liquids, solutions). The systematic principles guiding these methods have had to be derived, until comparatively recently, almost entirely from the study of fluid systems ; and thus it happened that very little was known about the fundamental in ternal arrangements and groupings of atoms and molecules, in side solids. But the study of the colloidal state has shown that the properties of substances and the qualities of materials are related not merely to fundamental arrangements and groupings of their atoms and molecules but also, in turn, to the higher aggre gation of these fundamental units into particles, micelles, crystal lites or whatever they may be called. X-ray analysis has shown, further, that a substance like sodium chloride, consisting of sep arate NaC1 molecules in solution, is when in situ in the crystal, an aggregate of linked, alternate Na and Cl atoms arranged in lines and planes, in orderly sequence : so that the whole crystal is really a single, ordered aggregate of atoms and its properties and qualities are related to that state or condition of aggregation.The chemistry of cellulose has been derived, of necessity, very largely from the study of its reactions to reagents which, of course, affect the state or condition of aggregation and it is prob able that it has never been possible to reverse chemical treatment to the full extent of restoring the cellulose to the state or condi tion of aggregation in which the plant formed it originally, and upon which its qualities and properties as cellulose material de pend. When, therefore, celluloses derived from different sources by different methods behave differently, e.g., towards acids or al kalis as already recorded, it may be either that they are not one and the same sort of cellulose or that if they are the same then their state of aggregation may be not the same. X-ray analysis has given some information on this problem though much remains to be done before its conclusions can be accepted with finality. The method depends upon the diffraction of X-rays by the planes of the atoms. By ingenious arrangements the diffracted rays are registered photographically on a film as a series of parallel lines of varying intensity and characteristic pattern. The method shows that the cellulose aggregates consist of crystallites : their arrangement in crystalline form is the same for cotton, ramie and wood. The artificial silks, excepting cellulose acetate, which is amorphous—show the same sort of crystallite units. But there are differences, however, which appear to arise in respect of the ar rangement of crystallites about the fibre axis : irregular arrange ments produce photographic ring diagrams and regular arrange ments produce point diagrams. Artificial silks (excepting acetate silk) have an intermediate arrangement : cotton treated with strong solution of sodium hydroxide (mercerized cotton) and washed without tension gives a ring diagram, but if it is washed under tension, a point diagram is obtained. Thus there is some direct evidence that the crystallites are probably identical in all these different materials and that differences of property may be related to differences of crystallite arrangement, more particu larly with respect to fibre axis.

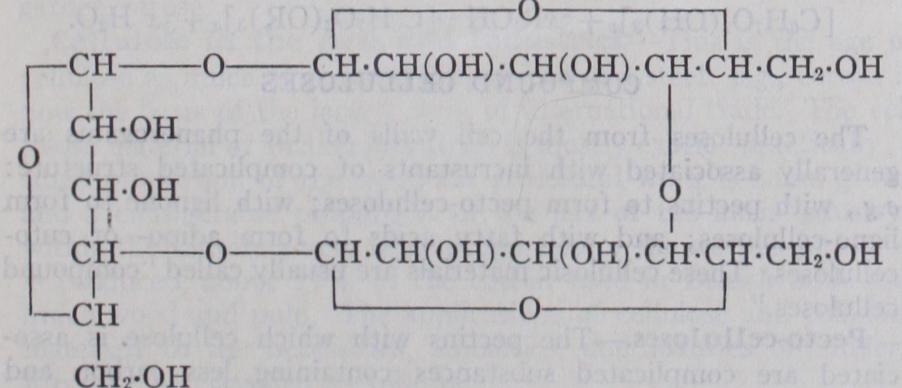

Empirical Composition.—The elementary composition of cel lulose indicates that it is a carbohydrate containing carbon 44.4%, hydrogen 6.2%, oxygen 49.4% whence the empirical formula C6H1005 is derived which is identical with that of starch: it is thus non-nitrogenous, though originating in the cell protoplasm. The cellulose from the cell walls of the lower cryptogams, when puri fied, does, however, retain 2-4% of nitrogen and, when hydro lysed, it gives glucosamine in addition to monoses and acetic acid. The cellulose of phanerogams is generally associated in the plant with other complicated substances with which it forms the so called "compound celluloses." Chemical Constitution.—Cellulose is a complex polysac charose or polyose of monosaccharoses or monoses : it may, in fact, be regarded as derived from monoses by the elimination of x molecules of water from x molecules of monose to form one molecule of polyose: thus This reaction is evidently of fundamental importance in plant physiology. Conversely, cellulose is hydrolysed by acids to give dextrose : G. W. Monier Williams (J. Chem. Soc. 119 [1921], 803-805) obtained 90-67% of the theoretical amount of crystalline dextrose. J. C. Irvine and E. L. Hirst (J. Chem. Soc. 123 518-532) showed also that cotton when methylated and hydrolysed gives a quantitative yield of 2 :3 : 6-trimethyl dextrose : they have consolidated these facts, taken together, into a formula which expresses the constitution of cellulose in terms of three dextrose residues, linked together in a ring : thus Various other formulae have been also suggested from time to time and it is still possible that no single formula will adequately represent the constitution of cellulose; but the evidence thus available appears to indicate that in the equation given above x=3.

Cellulose and Water: Hydrated Cellulose.—The interac tions of cellulose and water involve questions of great interest and these questions are still open. So-called "hydrated cellulose," in which water is intimately associated with cellulose, may be produced in a number of ways ; e.g., (a) by mechanical comminu tion and pressure of cellulose with water, and this is essentially the method used industrially in the papermaker's "beater"; (b) by the action of strong solutions of certain salts such as zinc chlo ride, calcium sulphocyanide, cuprammonium solution (Schweizer's reagent), etc., and this is essentially the method used for making vulcanized fibre, cuprammonium silk and willesden goods; (c) by the action of strong solutions of alkalies, and this is essentially the mercerizing process used in the cotton textile industries and also the first step in the making of viscose; (d) by strong solu tions of acids, and this is essentially the acid process of parch mentizing paper ; (e) by regenerating cellulose from its esters, and this is essentially the process of making artificial silks- excepting acetate silk. Hydrated cellulose is cellulose associa ted with more or less water (even up to 90% water to to% cellulose) to form a more or less swollen or gelatinous mass. The swelling of solids by imbibition of liquids and their dispersion in the liquids is quite a well known and common phenomenon : thus gelatine and starch will swell and, on warming, disperse in water : gelatine swells greatly, starch hardly at all, both disperse readily. On the other hand, cellulose neither swells nor disperses in pure water though it "hydrates" when it is subjected to continuous mechanical comminution and pressure, as it is in the "beater"; but in the various other circumstances detailed above it does show effects very similar to ordinary swelling and dispersion. The ques tions then arise, What is this "hydration" and is it analogous to swelling (imbibition) and dispersion as known in other substances such as those named? J. R. Katz (Physik. Zeit [1924] 25, 321) has examined the phenomena concerned by X-ray analysis and the diagrams he obtained, being in general the same for hydrated cellulose as for cellulose itself, appear to indicate that the water taken up is inter-crystallite rather than intra-molecular; the process would then be imbibition. It was also found, however, that when strong sodium hydrate solution is the hydrating agent a different X-ray diagram is obtained for the hydrated, alkali-cellu lose produced and when the sodium hydrate is removed, by wash ing, the diagram for cellulose is obtained anew : this appears to indicate that the action in this instance is rather different, and re versible. The balance of evidence favours the interpretation that the hydration of cellulose is, for the present, to be regarded as a physical association of water with the crystallites of cellulose and not as an entry of water into the molecules. In cellulose hydrate, therefore, the water is not to be considered as held like the water in salt hydrates, called water of crystallization, though the nomen clature is the same. A definite salt hydrate such as Barium Chlorate, when dehydrated at constant tempera ture, will give up all its water at a definite and constant pressure equal to its vapour pressure at that temperature. Hydrated cellu lose, on the other hand, when dehydrated, gives up its water at pressures falling gradually and continuously and without sign of constancy at any stage : this is characteristic of all systems in which water is held physically, i.e., under inter-molecular rather than intra-molecular forces. At the same time it is also true that a certain relatively small proportion of the water might also be present bound within the molecules without its presence being discoverable in the presence of so large an excess of the physically held water, which would probably mask its presence. It cannot be said with absolute certainty, therefore, that the possibility of a definite hydrate of cellulose is altogether excluded. The hydration of cellulose is a factor of great importance in the economy of the plant, in determining the conditions of equilibrium between the water content of the cell wall and the sap. It is also no doubt a factor of great importance in the seasoning of timber.

Cellulose and Alkalis.

Though cotton cellulose is remark ably resistant to dilute alkalis, with a 15-20% solution of, e.g., sodium hydroxide its ribbon-like fibre, with reticulated walls, swells out into a smooth walled cylinder. This was first noticed in 185o by John Mercer and in 1889 H. A. Lowe discovered that simultaneous stretching, to resist the contraction consequent on the swelling, imparted characteristic lustre to mercerized cotton. The quantity of sodium hydroxide thus taken up by the cellulose corresponds to some such proportions as but whether or not it is in chemical combination or in some physical association with the cellulose is not finally decided though more recent investigators appear to think the available evidence is more in accord with chemical combination than with physical association, and the work of J. R. Katz, referred to above, tends toward that conclusion. Oxides such as those of lead, manganese, barium, iron, aluminium and chromium are also taken up by cellu lose in some sort of association, the cellulose scarcely changing in appearance (excepting colour), and industrial application is made of the fact in the dyeing and printing of fabrics. These effects are mainly colloidal, adsorption effects.

Cellulose and Acids.

Acids act upon cellulose according to their nature and their concentrations. Dilute acids or acids dried on to the fibre produce chiefly hydrocellulose, which is an indefi nite product, perhaps consisting of small quantities of bodies of the nature of dextrines associated with unchanged cellulose. Stronger acids at first hydrate or parchmentize and finally hy drolyse cellulose to form dextrines and simple sugars. Under con trolled conditions strong acids will react with cellulose to form esters. Hydrocellulose produced by the action of dilute acids or as recovered by, e.g., the saponification of cellulose acetate, is soluble in alkali solutions, it reduces Fehling's solution, it forms esters more easily than does cellulose to give brittle substances of no in dustrial value and it has a greater affinity for dyes, such as methy lene blue, than cellulose has. The constitution of hydrocellulose has been the subject of much investigation and much speculation with the only result that it has not been possible to distinguish its elementary composition from that of cellulose itself.

Cellulose and Oxidants.

Oxidizing agents such as nitric acid (6o%), chloric acid, chromic acid, permanganates, hypochlorites, hydrogen peroxide and even air itself in presence of moisture and certain salts (the rotting of moist cotton cloth or rope in contact with iron is well known) or under the influence of strong sunlight, as in the tropics especially, change cellulose into oxy cellulose with ultimate disintegration of the fibre and the forma tion of such substances, of low molecular weight, as carbonic and oxalic acids. Oxycelluloses contain free aldehydic groups, are eas ily attacked by hydrolysing agents and are decomposed by boiling with dilute hydrochloric acid to give relatively large yields of f urf Ural. Oxycelluloses reduce Fehling's solution, have affinities for dyes and in general are difficult to distinguish from hydrocellu loses : esters also can be formed. The disintegration of cotton fabrics and of overbleached paper is usually referable to the formation of oxycelluloses.

Cellulose Esters.

Cellulose forms compounds called esters by reactions in which it behaves as a tri-hydric alcohol C6H702(OH)3x. With, e.g., nitric acid, the hydrogen of the acid and the hydroxyl of the cellulose are eliminated as water and groups replace one, two or three of the OH groups to form the mono-, di- or tri nitrates. To get the higher nitrates it is not sufficient to use nitric acid alone but strong sulphuric acid must be used with the nitric acid. After the reaction the cotton, which is usually used because of its freedom from hemicelluloses, has hardly changed its ap pearance, but it will be soluble in alcohol-ether if the di-nitrate and insoluble if the tri-nitrate : commonly, various mixtures of the nitrates will arise with varying conditions of nitration and much research work has been done in adjusting these conditions to specific purposes, particularly for the explosives industries. The di-nitrate, soluble in alcohol-ether, is familiar by the name of collodion and it is the basis of Chardonnet, collodion or nitro arti ficial silk and also the celluloid, film, lacquer and plastic mass in dustries. The tri-nitrate is insoluble in ether-alcohol but soluble in nitro-glycerine and in other solvents : it is, of course, of very great importance as an explosive. Cellulose reacts also with acetic anhydride to form mixtures (probably) of the acetate esters and, in presence of sulphuric acid or some other suitable substance act ing as catalyst, the tri-acetate may be obtained, which is insoluble in acetone but soluble in chloroform: this acetate on hydrolysis yields 62.5% of acetic acid. If, however, this acetylation is car ried out in the cold and, after completion of the acetylation, the product then heated, a change occurs which is probably a change of aggregation accompanied by partial hydrolysis and the tri acetate, insoluble in acetone, passes into a form soluble in acetone and of good spinning quality. On hydrolysis, it yields about 55– 58 % of acetic acid.

Viscose.-The

sodium xanthogenate ester, or viscose, is the basis of the viscose artificial silk industry which provides about 88% (1927) of the world's output of artificial silk. The reaction was patented by Cross and Bevan in 1892. High grade, bisulphite, wood-pulp is most usually, and cotton linters sometimes, used in making viscose industrially. It is treated with mercerizing (17%) sodium hydroxide solution for two hours, the surplus solution is then squeezed out and the resultant alkali-cellulose is torn into crumbs which are matured for 24 hours or more in a closed ves sel: at this stage 6occ. of carbon bisulphide per 1 oo grams of air dry cellulose used, are added and the crumbs then gradually swell and become deep-orange coloured and gelatinous. After the further addition of an appropriate quantity of water and so dium hydroxide solutions, and waiting a day or two, the fluidity will have increased so that the viscose may be spun : after some days the viscose begins to become more and more viscous until, finally, cellulose (reverted, hydrated cellulose) separates out as a congealed mass which can be dried to a very hard and dense material called "Viscoid." In the artificial silk industry the spun viscose filaments are immediately reverted to cellulose by im mersion in a "setting" solution of sodium sulphate and sulphuric acid or other appropriate substances. The reactions of this re markable process are not yet well understood. The quantity of sodium hydroxide required in the mercerizing stage is in the pro portion of cellulose units to 1-NaOH: the reactions there after, with carbon bisulphide and the reversion to cellulose (hy drated), may be represented as follows : It is noteworthy that it has been possible to prepare only the mono-sodium xanthogenate ester. Cellulose esters of formic acid and also esters of the higher fatty acids, such as stearic acid, have been prepared : the latter are of interest as being probable con stituents of cork and other cuticular "compound celluloses." Ben zoyl and other aromatic esters have been also prepared.