Cement

CEMENT. The word "Cement" apparently was first used of a mixture of broken stone, tiles, etc., with some binding ma terial, and later it was used of a material capable of adhering to, and uniting into a cohesive mass, portions of substances not in themselves adhesive. The use of cementing material dates from very early days, and it is probable that adhesive clay was one of the first materials used for uniting stones, etc. Bitumen probably was also used for the same purpose, while the use of burnt gyp sum, and also lime, dates back to the time of the Egyptians.

In its widest sense the word "cement" includes an infinite va riety of materials and ranges from the clay used to bind stones and other materials together to form the natives' huts in tropical countries, or the clay in the sand used by small boys to make sand models, up to the modern rapid hardening cements which are capable of binding three times their own weight of sand together in such a way that, at the end of 24 hours, they will stand a com pression of several thousand pounds per square inch. It also includes those materials which join individual crystals together to form masses of rock, etc., such as the cementitious material which joins the grains of sand together in a sandstone, and ultimately merges into glues, solders and adhesives in general, between which there is no sharply defined line of demarcation.

In its more restricted sense, particularly if it is unqualified and used in connection with building and engineering, the word prac tically always means Portland cement, as this is by far the most important used at the present time, the world's output amounting to millions of tons per annum. A fairly full descrip tion of this cement is therefore justified, and a brief description of other cements will be given towards the end of this article.

Portland

cement is made by burning a mixture of calcareous and argillaceous material to clinking tem perature, and grinding the resulting clinker. The mixture may be a natural one, such as the marls, or an artificial one, such as chalk or limestone, for the calcareous material, and clay or shale for the argillaceous material. The binding qualities of modern ce ments are very considerable, and it is possible to make good con crete from properly graded sand and ballast with the use of I part of cement to 12, or more, parts of aggregate; but, as it is not always possible in practice to obtain a thorough distribution of cement throughout the mass, it is customary to use a larger pro portion of cement, e.g., parts of cement, sand and gravel, and, for a better quality concrete, 1 part of cement to 2 or 3 parts of sand, and 3 or 4 parts of gravel. A good cement mortar can be made from I part of cement to 4 or 5 parts of clean sharp sand, free from clay. If the mixture is too rich, e.g., equal parts of sand and cement, there is danger of cracks due to shrinkage, and apart from this the extra strength gained by using a greater proportion of cement than 1 to 3 of sand is so small that the additional cost is not justified.

History.

Very little definite information about the prepara tion and uses of cement can be found before the 18th century. Various districts gained reputations for the special qualities of their lime cements, such as the power of setting hard under water, but the reasons for these special qualities were not known until the last century. John Smeaton was one of the first to make any serious attempt to grapple with the question of the cause of the varying hydraulic properties of different lime cements. In 1756, whilst engaged on the construction of the Eddystone light house, he made a series of experiments to find the best cement capable of hardening under water. The result of these experi ments revealed the fact that the best hydraulic limes were made from limestone containing an appreciable quantity of clay. This led to a number of investigators carrying out experiments. In 5796 Parker invented his "Roman cement," which was made by "reducing to powder certain burnt stones or argillaceous produc tions called `noddles' of clay." This cement "will set . . . in 10 or 20 minutes either in or out of water." The raw materials for Roman cement were burnt to just short of the vitrifying tempera ture, whereas for hydraulic lime the raw materials were heated to a much lower temperature, which was just sufficient to decom pose the calcium carbonate. This was a distinct advance, as the overburnt or vitrified pieces of lime had formerly been picked out and rejected as being useless for mortar.Vicat, in 1813, made a series of experiments on the effect of adding different clays in varying proportions to slaked lime, and then burning the mixture. The success of these experiments led other investigators to try artificial mixtures of clay and cal careous materials and in 1822 Frost brought out his "British cement," which was soon followed by Aspdin (18 24) with "Port land cement." Both of these, however, were hydraulic limes, in that the mixtures were only calcined and not clinkered. Aspdin was apparently the first to use the word "Portland" to define a particular type of cement, although Smeaton, over half a century earlier, had said that cement made from these materials would "equal the best merchantable Portland stone in solidity and durability." His "Portland cement" was, of course, quite differ ent from modern Portland cement, but nevertheless the colour and properties of concrete made from this cement were somewhat similar to Portland stone.

By this time (182o-3o) works were springing up in various parts of the country where the raw materials were suitable ; Parker's "Roman cement" was manufactured at Northfleet, Kent, "British cement" was made by Frost at Swanscombe, and the Aspdins were making "Portland" cement at Wakefield and Gates head. This Portland cement, as mentioned above, was more of the nature of hydraulic lime ; but about 1845 Mr. I. C. Johnson, who was then manager of Messrs. White & Sons' works at Swanscombe, Kent, produced a cement of the modern Portland cement type, by burning the raw materials "with unusually strong heat until the mass was nearly vitrified," and this clinker, when finely ground, made a cement which was far in advance of the ordinary type produced at that time.

During the next few years many works started making true Portland cement, both in Britain and in other countries. In France, Dupont and Demarle were delivering fairly large quan tities of Portland cement in 185o from their works at Boulogne sur-Mer and the demand continued to grow. Naturally with such a demand, and with such scanty knowledge as to the special re quirements necessary for ensuring the production of good sound cement, a large quantity of inferior material came on to the market, and failures resulting from this gave the cement a doubt f ul reputation. Investigations for improving the quality of ce ment continued with moderate results. Grant's tests, in 1865, show an average tensile strength of 353.21b. for 24 sq.in. (i2in.X r yin.) cement and sand briquettes (I: i) at seven days (1571b. per sq.in.), while in 1878 a tensile strength of 5oolb. (2 4in. bri quettes), i.e., 2221b. per sq.in., was specified for briquettes made from 6 parts of cement to r o parts of sharp sand. This may be compared with modern rapid hardening cement, which, with i part of cement to 3 parts of standard sand, has a tensile strength of over 5oolb., and sometimes over 600lb. per sq.in. after 24 hours.

Manufacture.

When cement was first made from "stone noddles," as in Parker's method, the stone was placed in a bottle kiln or dome kiln ordinarily used for burning lime. When at a later date artificial mixtures of chalk and argillaceous materials were used, it was found that the best and most intimate mixtures were made by beating clay and chalk into a thin slip or slurry with water. This slurry was then allowed to stand in large set tling tanks, or "backs," until the material had settled, and the water was drawn off and the deposit dried and burned. The time taken for the settling and drying of the raw materials was so great that efforts were made to improve the kiln (which, of course, could only be fed with dry material) by utilizing the waste heat for drying the slurry. One of the first of these was the chamber kiln of I. C. Johnson, which consisted of a long horizontal cham ber connected with the top of the ordinary kiln, so that the hot gases from the latter had to pass through the chamber on the way to the chimney stack. The liquid slurry, either from the "backs" or direct from the washmill, was placed on the floor of the chamber and was effectively dried by the hot gases passing over it, providing the layer of slurry was not too thick. The chamber had to be of considerable length in order to provide floor space to dry sufficient slurry for a full charge of the kiln, and im provements in the direction of shortening this were made by Batchelor and others, by providing two or three floors one above the other. Coke was used for burning the raw materials and ranged from 8-9cwt. per ton of clinker. In 1870 Goreham pat ented his method of grinding his slurry with burr stones, thereby producing a better slurry and containing only 4o-42% of water, a proportion much less than was usual at that time, which, of course, facilitated drying. The construction of the bottle kiln, even in its improved form, the chamber kiln, necessitated inter mittent firing, as each charge of fuel and dried slurry had to be built up by hand. Experiments with the object of doing away with this costly intermittent method led to the development of shaft kilns, with continuous burning of the raw material. The shaft kiln, as its name implies, consists of a vertical shaft, the top of which leads into a chimney. A few feet from the ground level removable bars are fixed across the shaft. On to these bars is placed a layer of coke, then alternate layers of dried slurry and coke until the kiln is filled. The coke at the bottom is fired, and this burns the raw material above it, while the hot gases pass through and heat the layers above. As the coke burns away the cement clinker drops on to the bars and heats the incoming air, while the burning zone rises to about half way up the shaft. The partly cooled clinker on the bars is removed from time to time and fresh layers of dried slurry and coke are put in on top. The process thus becomes continuous, and the loss of time in ing for the kiln to heat up and cool down, together with the sultant loss of heat, which is unavoidable with the chamber kiln, is entirely overcome in the shaft kiln. Modifications of the shaft kiln were patented by Dietszch (fig. 1), Stein, Schneider and others, and the different types became - known by the names of the patentees. The next improvement was the use of forced draught instead of natural induced draught from the neys, and tests on a standard Schneider kiln showed an crease in output from the normal 7o tons per week to 150 tons per week when using mechanical draught.One of the weaknesses of the shaft kiln—or a fixed kiln—is the difficulty of ensuring even burn ing of the clinker, some of it being under burnt while other por tions were heavily clinkered, and various mechanical improve ments have been made in the grate with the object of keeping the whole of the material in the kiln on the move by the continuous withdrawal of the clinker. The improvements in the shaft kiln reduced the quantity of fuel required from 70 to 8o% of the weight of good clinker produced by the old kiln to 20 to 30% (dried slurry being used in both cases) . This economy of fuel and the small amount of handling required, together with low capital cost, render the shaft kiln method suitable for use where the small output does not justify the cost of the rotary kiln.

Other methods of preventing the waste of heat resulting from the heating up and cooling of the old type of kiln were investi gated. One of the most successful was the Hoffman Ring kiln, which consisted of a number of kilns arranged in a ring round a central chimney. The flues from the kilns are so arranged that air, which is heated by being drawn through clinker which is cooling, is used for burning the fuel in the next kiln or two, and the hot gases are drawn through the other kilns to heat the raw materials before passing into the main flue. These ring kilns are very economical with regard to fuel but require skilled hands for charging, and the labour costs are high.

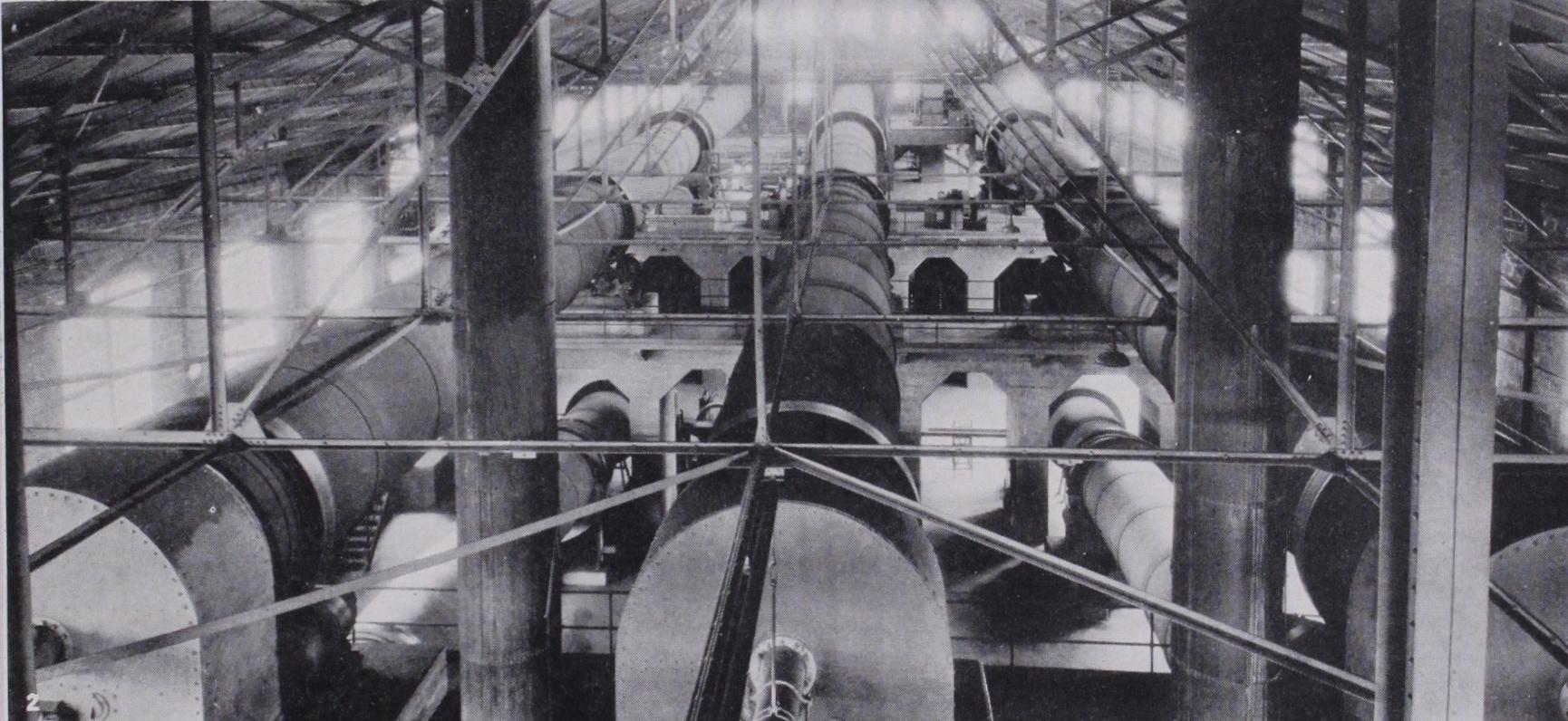

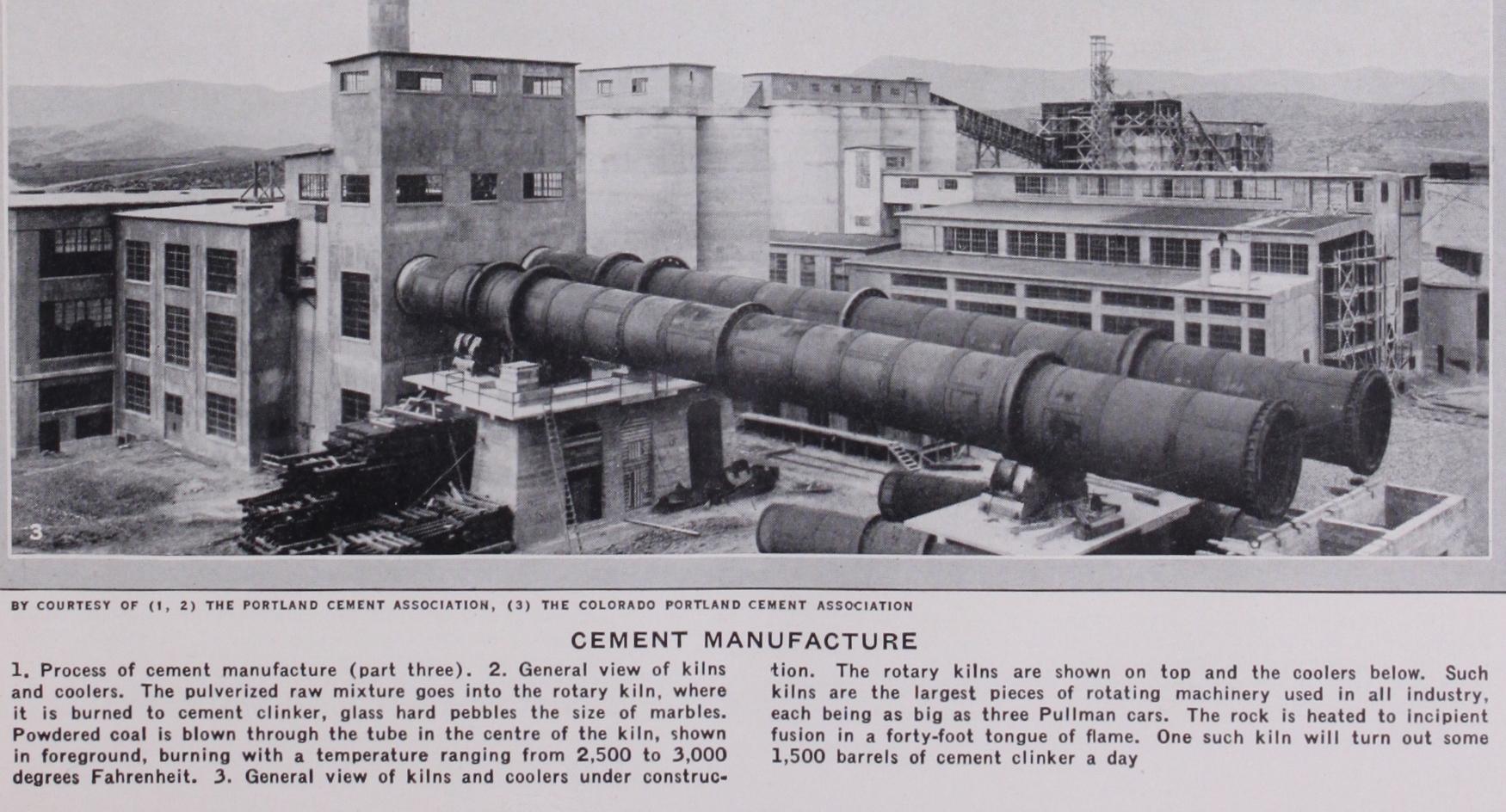

Another method, which laid the foundations for the modern rotary kiln process, was devised by Thomas Russell Crampton, who in 1877 patented a method for burning "Portland and other cements in revolving furnaces heated by the gases resulting from the combustion of coal or carbonaceous material" or "by the combustion of air and powdered carbonaceous material." In 1885 Frederick Ransome patented a method of burning dry powdered materials in a rotating cylinder by means of which he hoped to obtain the finished product from the kiln in a powder form sufficiently fine for use without further grinding, evidently overlooking the fact that clinkering is an essential process in the manufacture of true Portland cement. He also stated that the raw material might be fed in either at the chimney end of the kiln or at the firing end, which suggests that he had not appre ciated the full value of feeding the kiln at the end opposite to that used for burning the fuel. Further improvements were effected by F. W. S. Stokes who, in 1888, patented a method of drying the slurry by passing the hot gases from the rotating kiln through a revolving drum on to the outside of which the slurry was fed. He also used another revolving drum for cooling the clinker, utilizing the waste heat for heating the air supplied to the fuel in the kiln. In 1895 and 1896 E. H. Hurry and H. J. Seaman ob tained various patents for improvements in cooling the clinker, arrangements for using powdered coal with an air blast for burn ing, etc., and various other developments have been made with the rotary kiln, until it has very nearly displaced all others where a large output of Portland cement clinker is required. Among the first rotary kilns erected was that at Arlesey (1887). This was 26ft. long and 5ft. in diameter, and forms an interesting com parison with those now in common use, which are 200 to 3ooft. long, and 82ft. to r 22ft. in diameter.

Modern practice

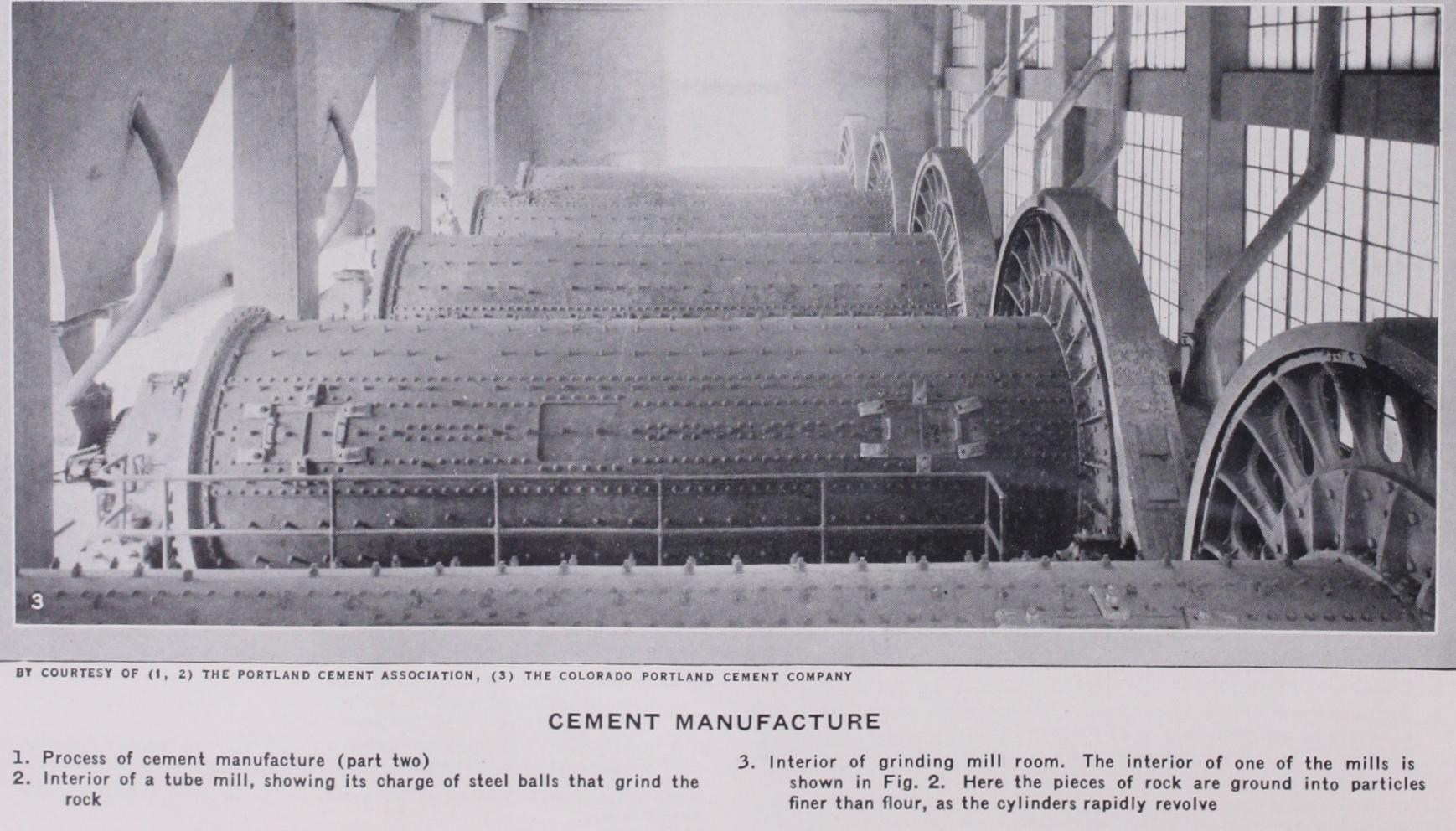

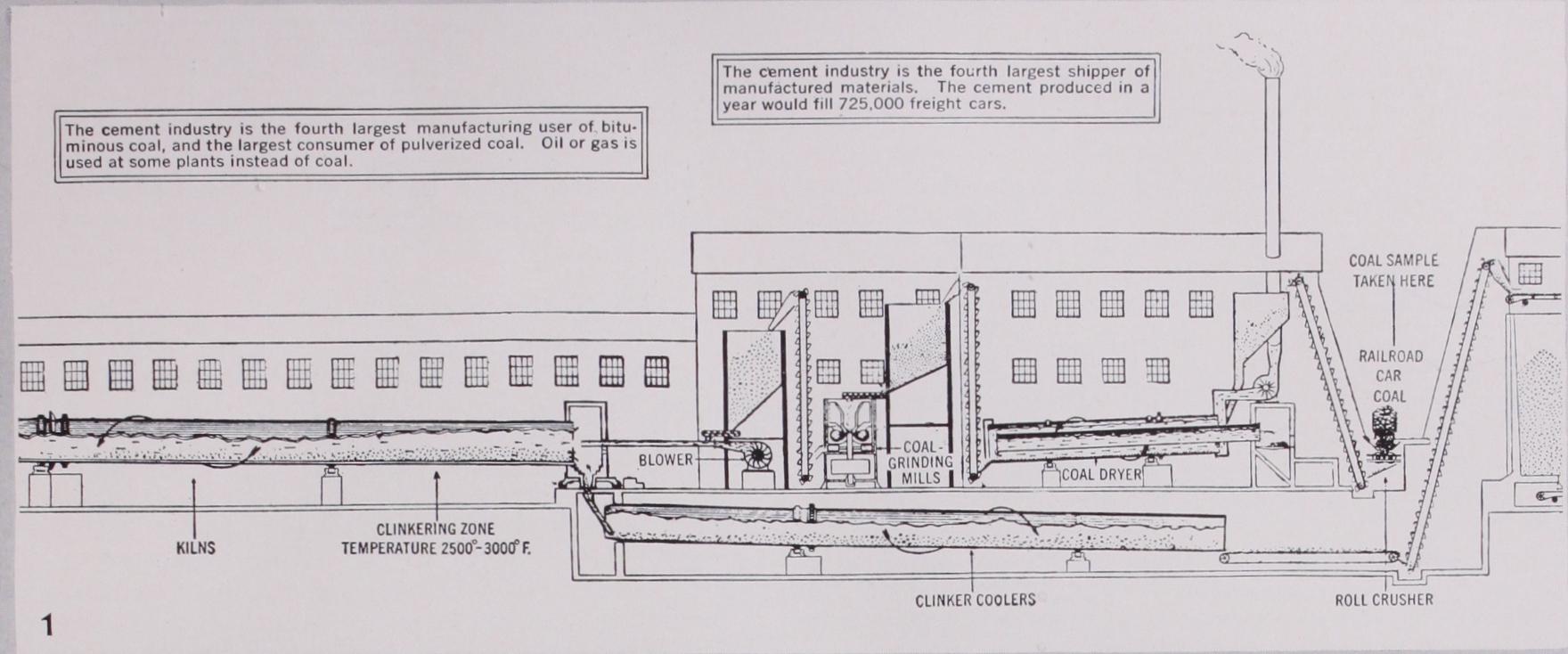

is to grind a mixture of suitable calcareous and argillaceous materials, either wet or dry, in such proportions as will give the correct composition to the finished cement. The wet ground material is pumped, in the form of a slurry contain ing about 4o% of water, into a series of large mixing tanks having a capacity of r,000 to 2,000 tons of slurry, and from these it is pumped into the kiln. The dry ground raw material is carried by a conveyor to the storage bins, and from the bins it is fed into the kiln after having been damped to prevent too much dust being blown up the chimney. The raw material, either in the form of slurry or damp meal, enters the kiln at the top end close to the chimney and meets the oncoming hot gases. As the kiln revolves the raw materials fall down towards the clinkering zone, having been first dried by the hot gases, and then having the carbon dioxide driven off from the calcareous materials. In the clinkering zone, where the heat is maintained by the combustion of powdered coal carried in by a blast of air, the lime of the calcareous materials combines with the silica and alumina of the argillaceous materials, and at this stage they partially fuse or clinker together, an action which is facilitated by the alkalies and iron oxide, etc., in the materials. The partially fused product or "cement clinker" passes from the lower end of the kiln to the cooler, where it parts with some of its heat to the air going to the kiln. The clinker, with the addition of a little gypsum or water to regulate the setting time, is then ground in ball and tube mills to such a fineness that the finished product—Portland cement— leaves a residue of under r o j'p, usually 1-3%, on a sieve having 32,400 meshes to the square inch.The raw materials consist of argillaceous or alumina and silica bearing materials and calcareous materials, the former including clay, shale, slate, etc., and some forms of slag, and the latter in cluding chalk, limestone, marine shells, etc., while many materials such as marls, gault clays, cement rock, etc., contain natural mix tures of both the calcareous and argillaceoua constituents.

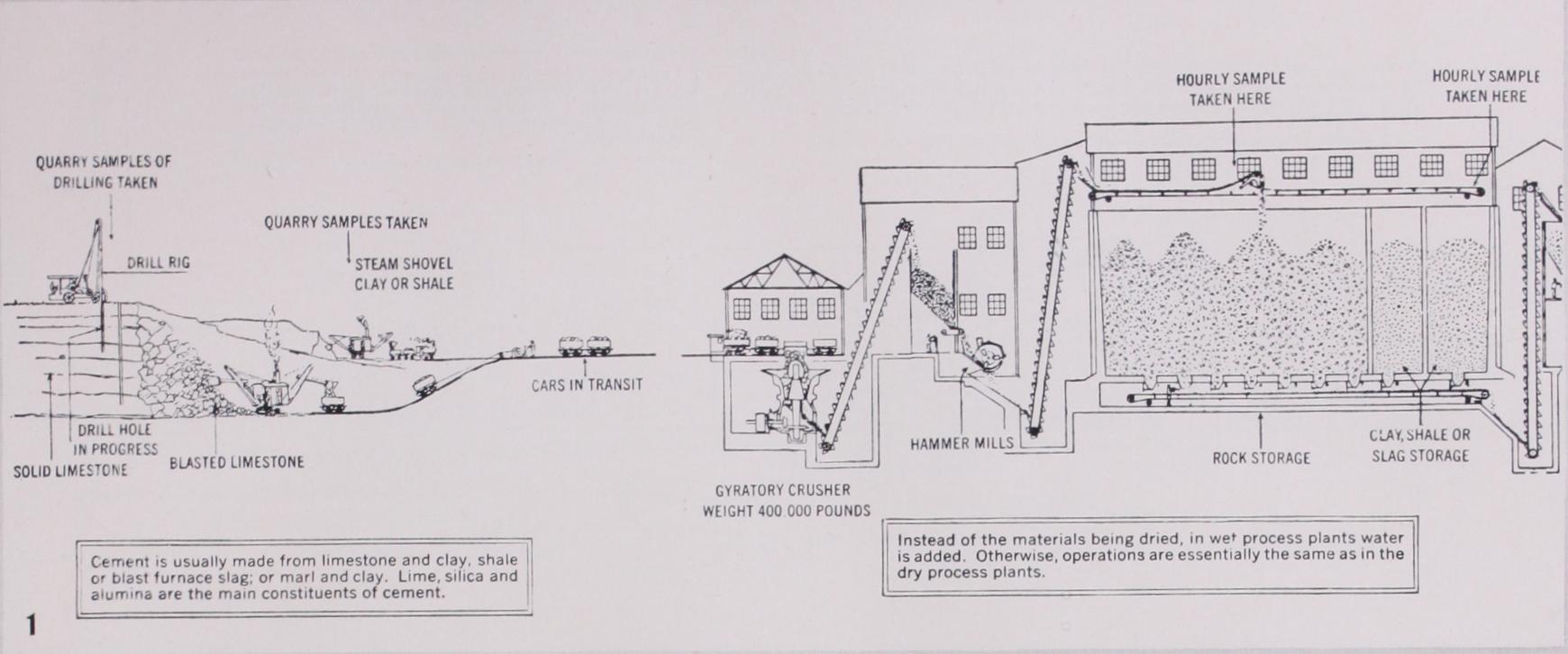

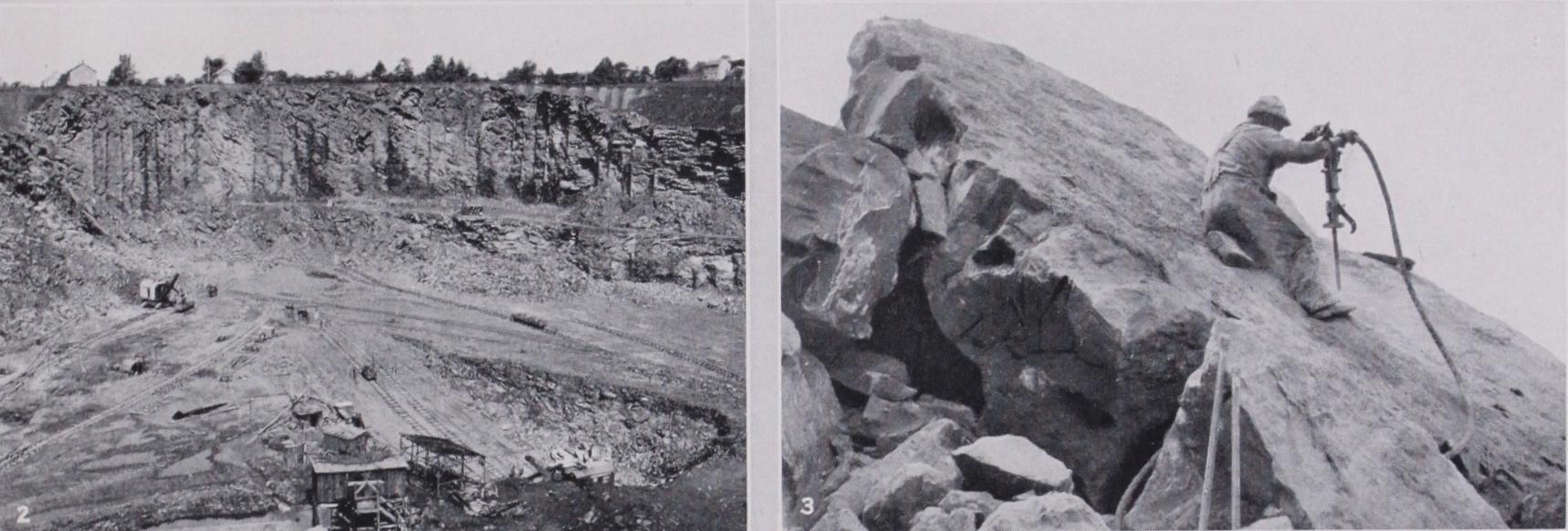

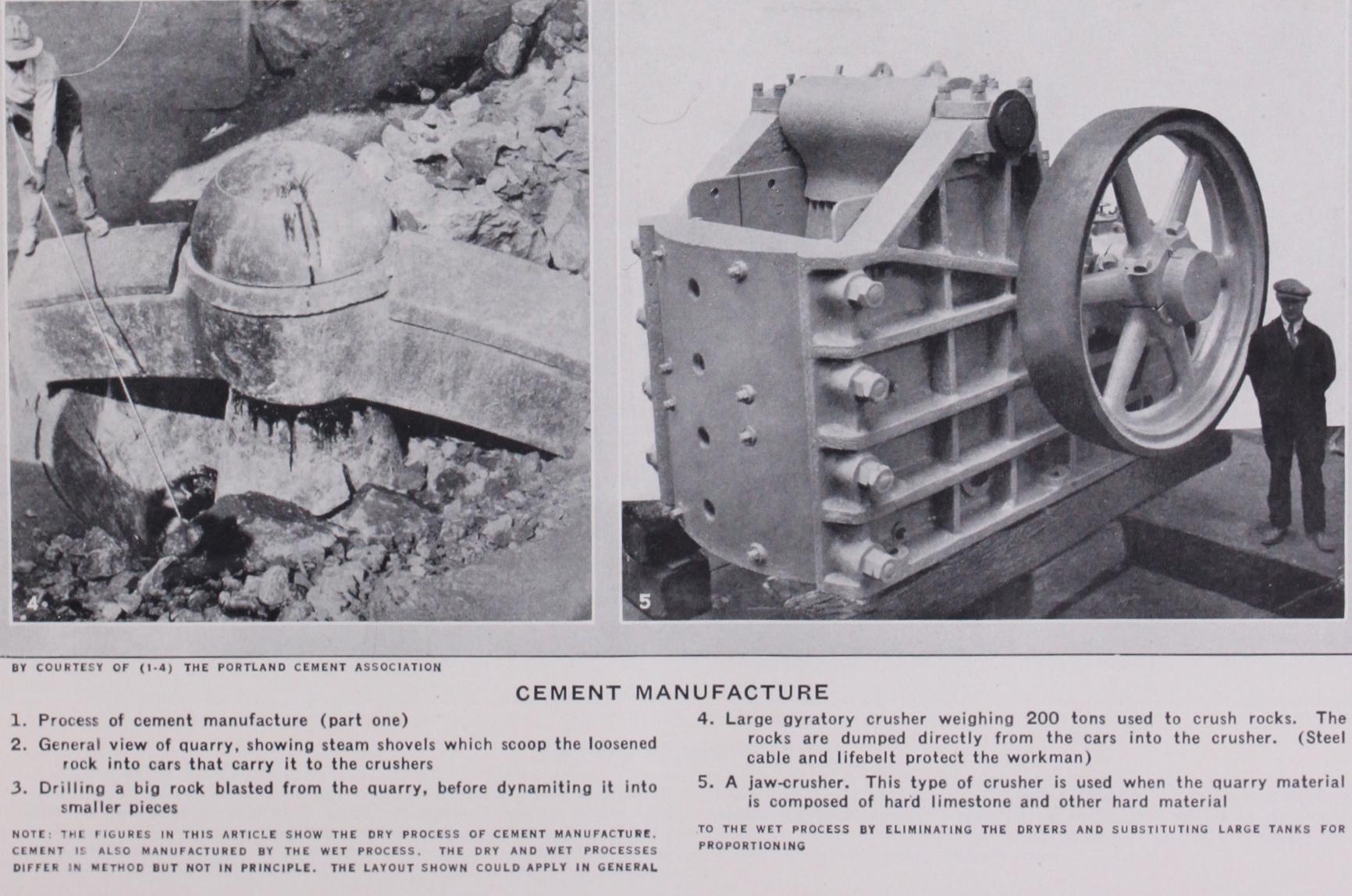

The method of obtaining the raw materials will depend on whether they are hard or soft. With soft materials, such as clay, marl, and soft chalk, a steam digger or scraper is used. After the "overburden" or top refuse material has been removed, a face is opened up in the material. The steam digger is brought up to this face, and the teeth of the digger bite into the material, and, on being lifted upwards, break or cut away lumps which fall into the bucket. The bucket, which holds from to 3 or more cubic yards, is swung round and emptied into a truck which is then taken to the washmill. For very soft materials, such as mud or clay under water, a dredging machine—a form of chain bucket excavator—is used. For hard materials, e.g., limestone, etc., the rock is blasted with an explosive such as gelignite, which will break it into pieces sufficiently small for the crusher to take. If the pieces are too large they are very difficult to handle or break again, and it is in regulating the position and depth of the bore holes, and the size of the charge, that the good quarry foreman shows his skill in obtaining the greatest quantity of loose rock of the right size with the least cost. The broken rock lying at the base of the quarry is picked up by a steam shovel or a grab, taking up 3 or more cubic yards at a time, put into trucks and taken to the mills.

Grinding Raw Materials.

The methods used depend on whether the materials are soft or hard. Soft materials are usually washed down with water until they form a slurry of the consist ence of cream, containing about 4o% of water. The trucks of marl or chalk and clay are tipped into a washmill, which consists of a large circular tank of concrete about r 4f t. or more in diam eter, with baffles and slotted screens (yin. to -Ain. slots) let into the sides. Water is allowed to run into the mill and a number of harrows suspended on chains from radial arms from the centre of the mill are caused to revolve at a rapid rate. These harrows break up the large pieces of chalk, etc., and by dashing the raw mate rials, suspended in the water, against the screens and baffles, break up the clay and chalk into such fine particles that about 98% will pass through a sieve having 18o meshes to the linear inch. If, owing to the presence of coarse particles of sand, etc., the slurry is too coarse, it may be necessary to finish it off in a tube mill. In America the 200 mesh sieve is commonly used.Hard materials are first put through a crusher which may be of the jaw type, in which the stone is fed in between two steel jaws set at an angle, one of which moves backwards and forwards with a rocking motion, or through a gyratory crusher, in which the gyratory motion of a central jaw causes a crushing action against an outer jaw, or through some other form of crusher suit able for large stone. The crushed stone is fed into smaller crush ers which may be one of the above types. or a hammer mill in which rods with hinged hammer heads are allowed to swing round rapidly and break the stone against stationary bars on the outer edge of the mill, or if the material is sufficiently soft it may be fed into crushing rolls.

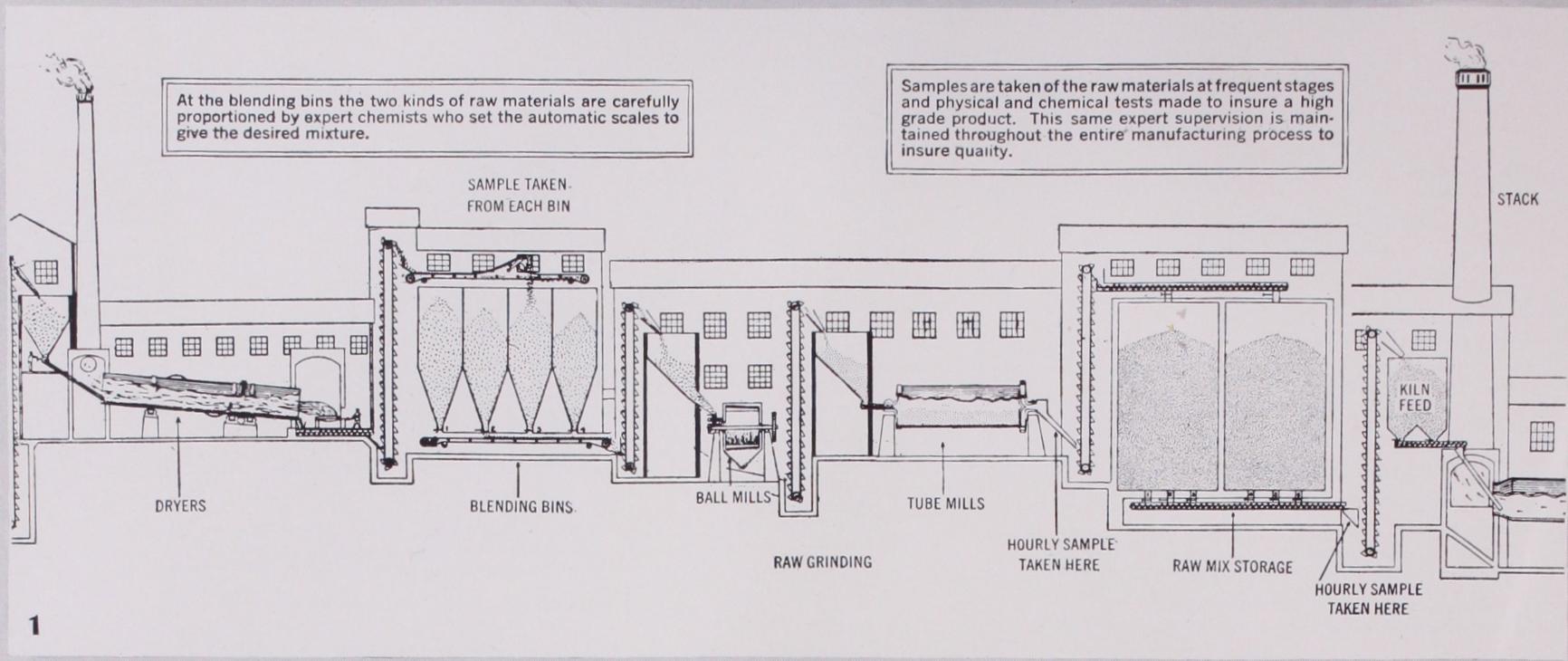

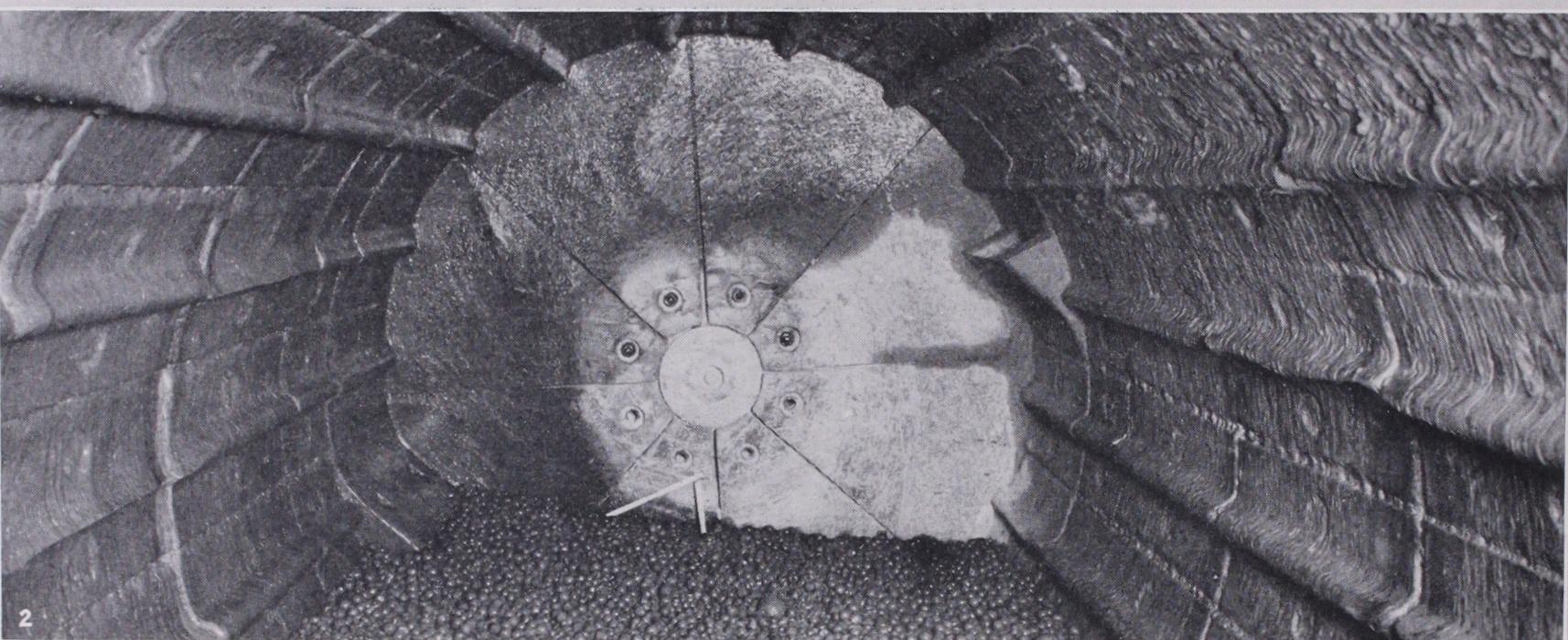

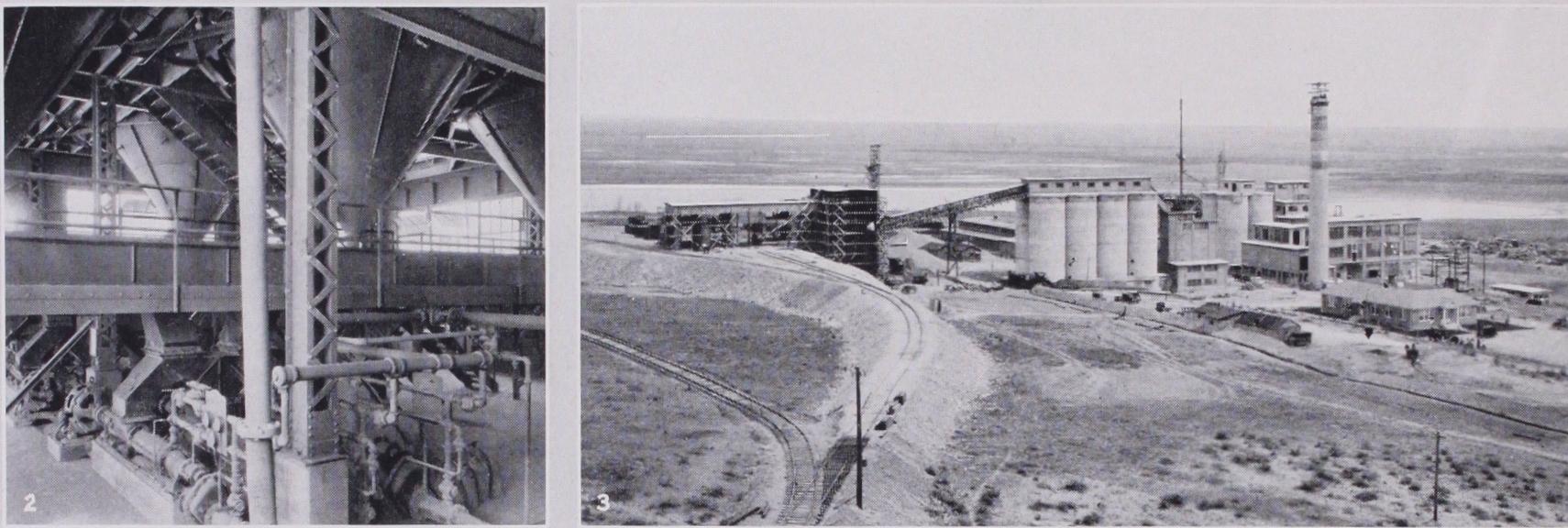

From this fine crushing the small stone is taken by a conveyor to the tube mills, and thence to the kiln. The process differs ac cording as the dry process or the wet process is used. In the dry process the limestone and shale, etc., are fed into the mills from the weighing machines or feed tables (which regulate the quan tity) in such proportions as will give a finished product of the cor rect composition. The mills may be of various types. In the ball and tube mill, separate or combined, steel balls falling over each other in a revolving cylinder have a pounding or hammering ac tion on the particles of stone between the balls. In the centrifu gal type of mill a heavy mass of steel is caused to revolve rapidly, and centrifugal force causes it to press against a stationary ring and exerts both a crushing and grinding action on the stone between the revolving weight and the ring. In the Fuller mill the revolving weights are large steel balls, in the Griffin mills they are large pestles, while in mills of the Hercules, Huntingdon, Sturtevant and Kent types they consist of movable or swinging rolls.

The finely ground raw meal from the mills is passed into the storage bin, whence it is fed into the kiln, after being damped if necessary. From this point the treatment is the same as the wet process. The advantage of the dry process is a small saving of fuel, and of water, if the supply is limited. The disadvantages are many, the chief one being the difficulty of getting the raw mate rials mixed sufficiently well to ensure even composition, and there also is the difficulty and extra cost of grinding the materials suffi ciently fine when dry, and of drying the materials if they are not quite dry. In England the dry process is practically never used, and in those countries where the dry process was in general use, such as America, there is a marked tendency to change over to the wet process.

In the wet process the limestone and shale from the feed tables, or weighing machines, are fed into the ball mill and then the tube mill, or into a compound mill where the two are com bined, and the requisite quantity of water added at the same time. The normal slurry coming from the mills contains about 40% of water, and leaves under 2% residue on a sieve having 18o meshes to the linear inch, but as it occasionally contains coarse particles which have passed through the mills, it is customary to put the slurry through a separator, usually of a centrifugal type, which rejects all the coarse particles. The slurry from the sump of the washmill, in the case of soft materials, the tube mill in the case of hard materials, or the separator, is pumped to the mixers, which are large tanks capable of holding i,000 to 2,000 tons of slurry. These mixers serve three purposes—(I) they allow of corrections being made in the composition of the slurry, (2) they overcome any temporary variation in the composition by dis persing it and mixing it with the large bulk, and (3) they give efficient storage, allowing the grinding plant to be shut down over the week end (and at night, if required) while the kiln continues to run. To prevent settlement in the tanks the slurry is continu ously kept on the move. The usual method is to have the mixer, about 6o-8oft. diameter, and I o–I 2 f t. deep, fitted with radial arms with the bearing in the centre of the mixer. From these horizontal arms are suspended vertical arms, which act as mixers, and these are geared together, so that while in the first instance they revolve round themselves, the resistance of the slurry against the walls reacts on the vertical arms and causes both the hori zontal and vertical arms to rotate round the centre, and the whole of the contents of the mixer is thus constantly stirred. In other types of mixers the slurry is kept in motion by suitable paddles, or by air being forced through from below. In the latter method it is customary to have deep mixers with a conical bottom, the main air supply being in the centre of the cone, while subsidiary air jets are distributed on the sides of the cone. Sometimes they have both air and mechanical arrangements, thus making a very efficient mixer.

From the mixers the slurry is pumped to a small tank at the top end of the kiln, whence it is fed into the kiln at such rate as the burner thinks necessary. The usual method of doing this is by a spoon feed, the revolving spoons dipping into the tank and delivering the slurry into the kiln. Occasionally the feed is regu lated by a variable orifice leading into a delivery pipe. Whichever of these two methods is used, it is the regular practice to keep the tank at constant level by over pumping and allowing the excess of slurry to run back to the mixer through an overflow pipe. Other methods, such as the spray feed and dewatering the slurry by means of vacuum filters, have been tried with some success.

Burning.—The most essential part of the manufacture of Port land cement is the complete chemical combination of certain con stituents, viz., silica, alumina and lime. The other constituents, particularly the iron oxide and alkalies, play their part but are subsidiary to the three main constituents. These readily combine at a high temperature, but at this temperature it is difficult to get the kiln lining to stand up, and therefore every means should be taken which will assist the chemical combination to take place at a somewhat lower temperature, and also prevent any excessive attack on the lining bricks. Fine grinding plays an important part in meeting the first of these two requirements, and the second is met by obtaining a coating of a more fusible slurry to adhere to the lining brick, and thus protect them.

The kiln itself consists of a cylindrical shell made of steel plates, lined with fire bricks for nearly the whole of its length. The length varies from I soft. to 3 5of t. or more, and the diameter from 8ft. to 14ft., usually with an enlarged diameter at the firing zone, so that the clinker may be allowed to "soak" at the high temperature. The kiln itself is carried on three to six tyres, ac cording to its length, and is driven by a gear ring usually fixed a little below the middle of the kiln. The expansion of the kiln is considerable, and therefore the tyres and gear ring are not riveted directly on to the kiln, lest they be fractured, but are fixed to metal bands riveted at one end to the kiln, and are also supported by guide blocks. As the kiln is set at an angle usually of I in 25, the tendency of the kiln to slide down, while revolving, is counteracted by having the faces of the tyres and the support ing rollers set at an angle. As a further precaution check rollers are fixed so that should the kiln slip down a little these rollers come into action on the side of the tyres and stop the kiln from slipping off the supporting rollers. At the upper end, where the slurry, or damp meal, is fed in, the kiln passes into the dust cham ber, through a joint which is reasonably tight to prevent loss of draught, and the hot gases, having deposited a large portion of the dust, are led into the chimney. The lower end of the kiln is fitted with a large adjustable hood set on rails, which allows of complete regulation of the ingoing air, the bulk of which is heated by passing through the clinker coolers, which may either be an extension of the kiln or a separate unit under the kiln, into which the white hot clinker drops. Through the centre of the hood is the coal injector, a metal tube through which powdered coal is blown by a powerful blast to supply the heat necessary for burning the clinker. Small doors are also fixed on the front of the hood, on the left and right of the coal inlet, and one below. The first two allow the burner, who is a skilled man, to see the type of flame being produced in the kiln, and the lower one enables him to see the clinker. Considerable care and skill are required in burning, and a good man can show his skill not only in producing maximum out put of highest grade clinker with the minimum quantity of fuel, but, given good plant, in prolonging the life of the kiln lining and preventing stoppages due to "ringing up," etc., caused by faulty and irregular burning.

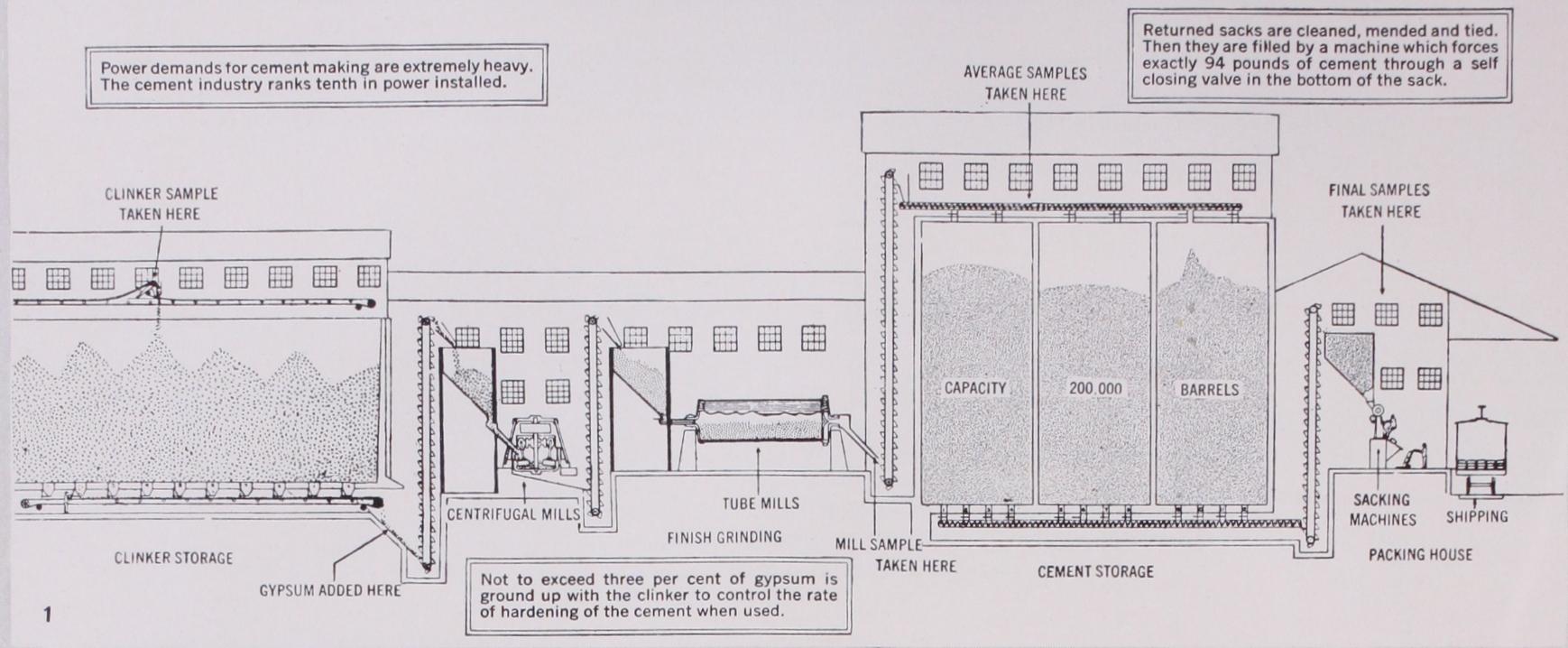

Clinker Grinding.—The clinker as it comes from the kiln is in a fairly stable condition, and may be stored for months in the open if necessary without any appreciable deterioration. This, however, represents so much locked up capital, and it is therefore customary to grind the clinker soon after it is made. Very fresh clinker appears to be a little tougher than clinker which has been allowed to stand a week or two, and this sometimes affects the power required for grinding. The clinker from modern kilns is usually small enough to be fed directly into a ball mill or a high speed mill, but if it is too large it is passed through a crusher first. As it is usually necessary to add a definite proportion of gypsum to the clinker in order to regulate the setting time of the cement, both the clinker and gypsum are passed over feed tables before being mixed and fed into the mills. The feed tables are simple devices for regulating the quantity of any material passing over them in a given time and consist of a revolving table, fixed scrapers and a vertical feed pipe, with an adjustable collar, just above the centre of the feed table. The material falls in a heap in the centre of the table, and as it revolves a portion of the mate rial is guided by the scrapers away from the heap to the edge of the table, whence it falls on to a conveyor and is taken to the mills. The heap in the centre is at once replenished from the feed pipe, and the size of the heap, and therefore the quantity removed by the scraper, is regulated by the height of the adjustable collar of the feed pipe above the table.

The mills used for grinding the clinker are of the same types as those described for the grinding of the raw materials. The type most frequently used for clinker grinding in modern plant in Britain is the compound mill, which is usually 7 or 8ft. in diameter and 3o to 4of t. long.

The fineness of the finished cement is specified by the British Standard Specification to be such that the residue on a sieve hav ing 32,400 meshes per sq.in. shall not exceed ro%. Usually the ordinary cement has from I to 3% residue.

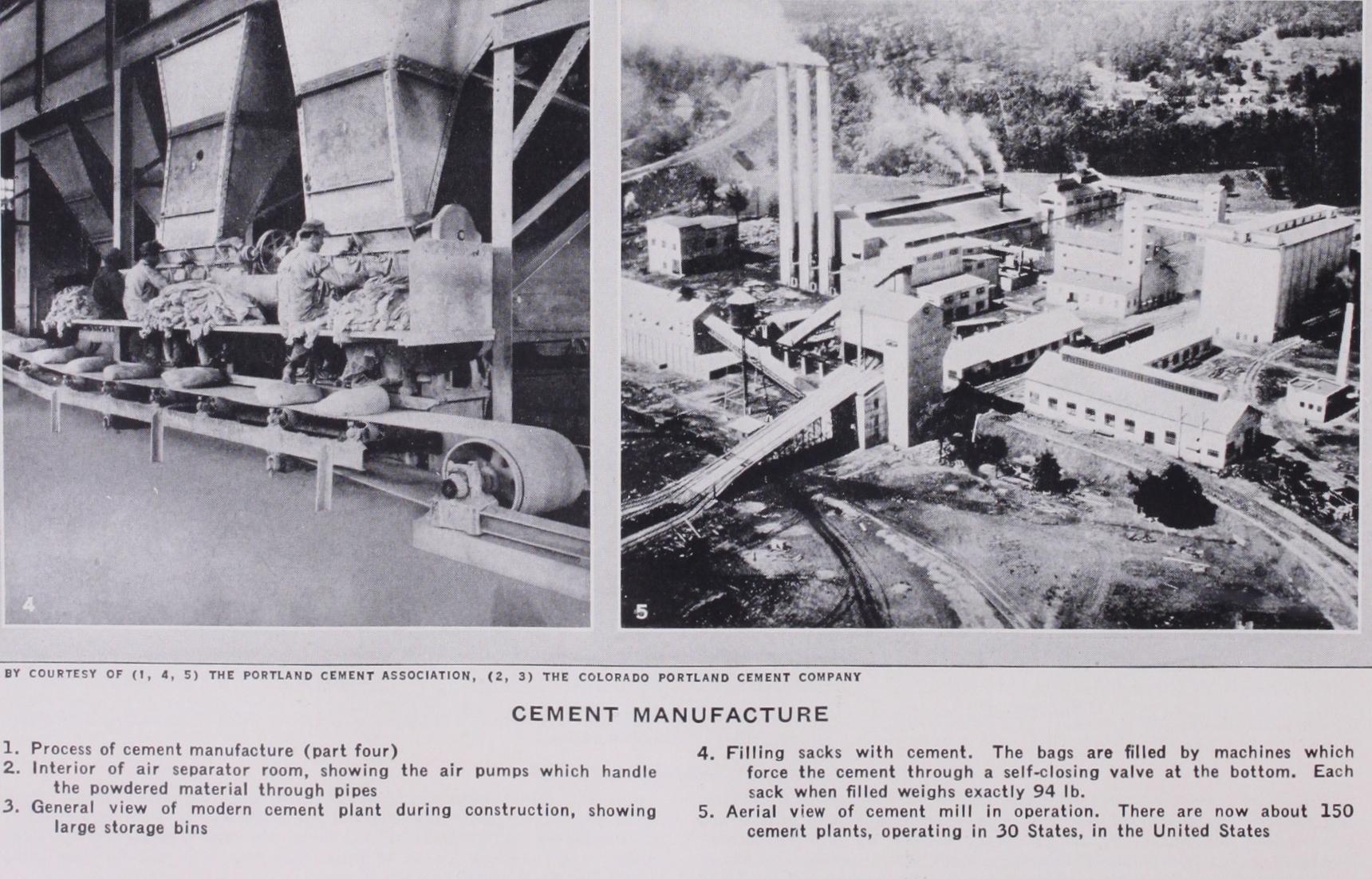

Storing and Packing.—The cement from the mills is deliv ered on to a belt conveyor, and then by means of bucket con veyors to the storage bins or silos. each of which holds from 250 to several thousand tons. The cement is drawn from these bins or silos as required and is filled into sacks, casks or paper bags reinforced with fabric. The packing is sometimes done by hand, but more often by mechanical means. In the Exilor method of packing. tubes from the bottom of the silo lead into the tops of two small chambers or cupboards. with one door which can be used to close either one of the two chambers. At the bottom of each chamber is a small weighing machine which at a predeter mined weight will drop and open the air valve. To work the machine. for sack filling. the operator fastens the mouth of the sack round the inlet pipe and closes the door. This starts a small electric air pump working, which makes a partial vacuum. suffi cient to suck the cement out of the silo into the sack. As soon as the correct weight of cement has been delivered into the sack the sack drops. opens the air valve, and by breaking the vacuum causes the flow of cement to cease. While this is taking place the operator removes the filled sack from the second chamber, puts a fresh sack on the inlet pipe, and swings the door round to close this chamber. the cycle of operations being repeated as often as required. In the valve packing machine each sack or paper bag is fitted with a little sleeve valve inside the bottom of the sack, with the opening at one end well inside the sack, while the other end opens outside the bottom corner of the sack. To fill the sack the mouth is first tied up. usually by wire twist ties, and the valve is slipped over the spout of the filling machine, the sack being upside down. Cement is supplied to the machines through a hopper and is pushed through the spout by a paddle wheel.

Lay-out of Works.

For the purpose of economy and effi ciency, considerable care must be exercised in the `'lay-out" of the works. so that the raw materials and coal are delivered at the places where they are to be used, and the clinker and cement stores are in the proper position for the minimum handling of these materials.Analysis and Tests.—In order to ensure that nothing but reli able cement reaches the market. standard specifications have been drawn up by different countries. Space will not allow of these being given in detail, but the British Engineering Standards Association Specification (192 5) gives a good general idea of the minimum quality demanded. although most of the best cements are far above this. The mechanical tests are as follow, and by the side are placed the results of tests made on an ordinary Port land cement of good quality.

With the specified sliding scale for increase of the sand bri quettes at 28 days, viz., M.; plus the strength at 7 days, at 325 lb. for 7 days, the strength at 28 days should be 36•81b. per sq. in. minimum. With 4781b. at 7 days, the 28 days' tests should be 499 lb. Actually this cement gave 616 lb., an increase of i 17 lb. over that specified.

Composition.

The composition of Portland cement varies over a somewhat wide range. The specification gives the following limits.Maximum Magnesia . 4-oCC Total sulphur, calculated as sulphuric anhydride 2-73% Insoluble residue . I- 5% Loss on ignition 3- o% Ratio of lime to silica and alumina (calculated in chemical equiva lents) is to be between 2 and 2.9.

The composition of English Portland cement varies according to the district. The two analyses given below show the difference. The first is from the Thames and Medway district. and the second from the Blue Lias deposits.

Uses of Portland Cement.—The demand for Portland cement for use in structural work continues to grow. and. in addition to this, Portland cement is being used for an increasing variety of purposes (see CONCRETE), which can only be briefly mentioned. Concrete, sometimes reinforced with iron or steel, is being used for all big structural buildings. engineering works, harbours. docks. ships. piers, bridges, piles, general building, artificial stone, roads (both foundation and surface), water towers. natatorium. lakes, etc.. and the facility with which the concrete can be placed in any position and the fact that local stone and sand can frequently be used to the extent of 5 to lc) parts to i of cement are very im portant points with regard to cost of labour and carriage, as com pared with that of stone. Concrete is also used for smaller articles such as telegraph poles. railway signal posts. sleepers, fencing posts. monuments, tombstones. coffins, troughs of various kinds. tiles. bricks, pipes (spun and moulded), paving blocks. manhole covers. etc. Very considerable developments have also been made in the use of cement for ornamental work. including not only that required for buildings. but sculptural work of all description. both large and small; and by the introduction of various aggregates, excellent substitutes for different ornamental stones have been made, frequently having improved weathering properties. Port land cement is particularly useful where there is much repetition of ornamental work, e.g., for the capitals of pillars, tracery. etc. In the case of stone each piece must be carved separately. whereas a few moulds will be sufficient for a large number of blocks of cement concrete.