Cephalopoda

CEPHALOPODA, a group of highly organized invertebrate animals of exclusively marine distribution constituting a class of the phylum Mollusca. Some 15o genera of living cephalopods are known, of which the octopus, the squid and the cuttlefish (qq.v.) are the most familiar representatives. The extinct forms, however, outnumber the living, the class having attained very great diversity in late Palaeozoic and Mesozoic times. Of extinct cephalopods the Ammonites (q.v.) and Belemnites are the most familiar examples.

The Cephalopoda agree with the rest of the Mollusca in gen eral structure and appear to have the closest affinity with the Gas tropoda (snails, periwinkles, limpets, etc.). They have a more or less elongate body (visceral mass) covered by a "mantle." The latter secretes a shell and encloses a cavity in which the gills are suspended. The alimentary canal is furnished with the character istic molluscan rasping tongue or radula. These animals differ from the rest of the Mollusca primarily in that the head and foot are approximated, so that the mouth is situated in the middle of the foot, and the edges of the latter are drawn out into a number of appendages (arms and tentacles). The area just above the edge of the foot, from which the epipodium of the Gastropoda is developed, is produced to form a peculiar organ of locomotion, the funnel. The majority of living cephalopods possess fins and their shell is in a reduced or degenerate condition, a tendency apparent in many fossil forms. In short the leading feature of cephalopod organization and the dominating theme of their evolution is the development of organs that subserve a vigorous aggressive mode of life unhampered by the heavy calcareous shell that is carried by their more sedentary and inactive relatives. Nevertheless the living Nautilus (q.v.) and many forms now extinct retain the shell in a complete condition.

For invertebrate animals the Cephalo poda attain a large average size and the genus Arc/iiteuthis (giant squids) are ac tually the largest living invertebrates, the Atlantic species Architeuthis princeps at taining a total length of 52ft. (inclusive of the tentacles). The shell of the fossil ammonite (Pachydiscus sep temradensis from Westphalia (Cretaceous) measures 6ft. Bin. in diameter and is the largest shelled mollusc. Though not such a flourishing group as they were in secondary times, the Cephalopoda are still one of the dominating groups of marine animals. They are the indomitable prey of whales and other marine carnivora and the relentless enemies of Crustacea and small fishes. The bizarre appearance of Cephalopoda, their sinister eyes and the secretive habits of some of the shore-living forms have made them a subject of legend among imaginative peoples. Modern authors have not hesitated to exaggerate the horrors of the attack of a giant squid or octopus ; and Denis de Montfort and Victor Hugo have invested them with a melodramatic violence that has taken root in popular fancy. Nor is this reputation for ferocity un merited, as far as attacks on human subjects are concerned.

Classification.

In the past decade the classification of the Cephalopoda has undergone a considerable amount of revision principally owing to the work of Naef and other German zool ogists. The following is the scheme drawn up by Grimpe (1922): Class. Cephalopoda.Sub class i . Protocephalopoda.

Order i. Nautiloidea.

Order

2. Ammonoidea.

Sub class

2. Metacephalopoda.Order i. Octopoda.

Sub order i. Cirrata.

Sub order

2. Paleoctopoda.Sub order 3. Incirrata.

Order

2. Decapoda.Sub order I. Sepioidea.

Sub order

2. Teuthoidea.Sub order 3. Belemnoidea.

It will

be seen that this scheme recognizes the fundamental distinction proposed by Owen, which separates Nautilus and its allies from the octopods, squids and cuttlefish. This distinction is without doubt sound, for it rests on the fact that, within the limits of our knowledge, the Nautilus has a more primitive or ganization than the rest of the Cephalopoda. It has a wholly ex ternal coiled shell, four gills and kidneys, and other features which we are justly entitled to regard as primitive. It must, however, be recognized that we can deal only with the shell of the extinct nautiloids and the ammonites and we do not know if the rest of their organization was like that of Nautilus. It is a fair inference, however, that the living and fossil nautiloids and the ammonoids are a natural group. Grimpe's scheme differs herein from the older classification in raising the main sub-divi sions to the status of sub-classes and in thus emphasizing their distinctness as is done in the case of the streptoneurous and euthyneurous gastropods. This is an advantage and may be safely adopted.The classification of the Dibranchia proposed by Naef and Grimpe involves a more fundamental change. In its primary di vision into Octopoda and Decapoda it follows traditional lines.

In its secondary division of these groups, however, it departs from the latter for reasons which appear to us well-founded. Among the Octopoda the fossil Paleoctopus merits recognition as representing a separate sub-order. It is, however, in the re organization of the Decapoda that the new scheme has most to recommend it. The recognition of the three sub-orders Sepioidea, Teuthoidea and Belemnoidea has the advantage of taking into ac count our knowledge of the phyl ogeny of the order, and mark ing the three great tendencies that can be recognized in the evolution of the decapod shell.

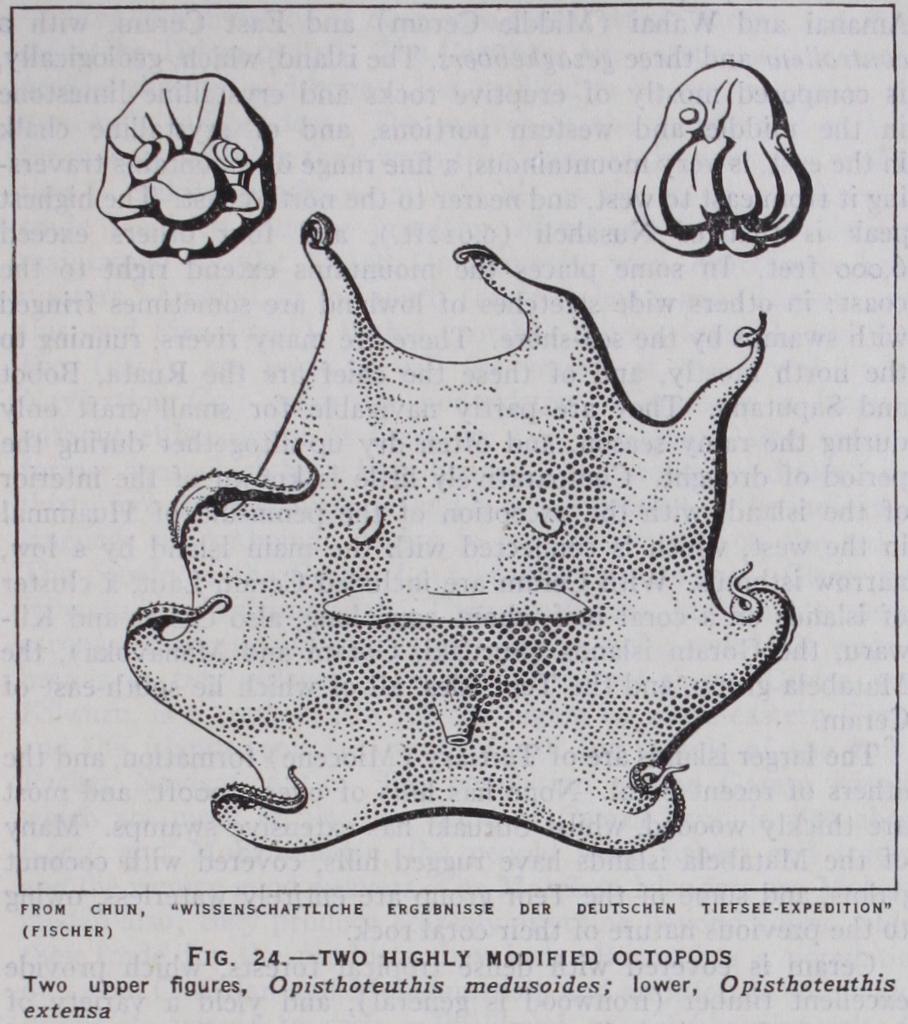

The older "Egopsida" are, as far as nearly all their living represent atives are concerned, preserved intact. But the Belemnite-like fossil forms are quite reasonably abstracted from them and placed in a separate sub-order. The older "Myopsida," which contained forms with radically dis similar shells, such as Sepia and Loligo, are resolved into two sections, one of which (Sepia, Sepiola, Spirula and certain ex tinct forms) is elevated to sub-ordinal rank (the Sepioidea), while the other (Loligo, etc.) is treated as a section of the Teuthoidea along with the Egopsida (as above restricted). It may be reasonably objected that this has the effect of placing forms such as Sepiola which, like Loligo, have a chitinous, non calcified shell in a different sub-order from Loligo and the Egopsida, and of disregarding certain points of similarity between the Loliginidae and Sepiidae. Nevertheless it is held that in spite of this fact, Sepiola and its allies are more closely allied anatomic ally to Spirula, which has the distinction of being the only living dibranch with a coiled and partly external calcareous shell, than to Loligo and the Egopsida, and that phylogenetically they can thus be attached to the sepioid stock. Concerning the affinities of Spirula, a good deal of controversy has taken place. It seems best to accept Chun's view that it is a sepioid form, as the rea sons set forth at length by him in his study of this interesting genus (tif-'issenschaftliche Ergebnisse der Deutschen Tiefsee Expedn. Bd. 18, 1915) are sufficiently convincing.

Anatomy and Physiology.

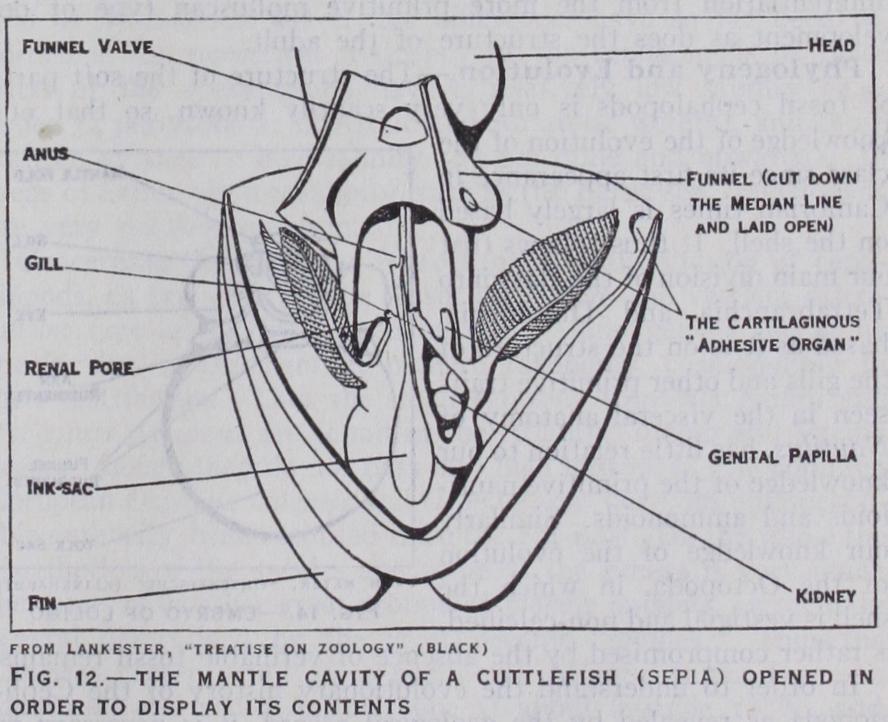

In fig. 3 is given a diagram illustrating the structure of a cephalopod. Though schematic, this diagram gives a very fair idea of the organization of such forms as the common cuttlefish, squid and octopus. The view has been widely accepted that in the Cephalopoda the surface of the foot has become very much shortened as compared with that of other molluscs, the length of the body being reduced, while its height is increased. This mod ification of what we may assume to be the original plan of mollus can organization is held to have been brought about by the foot shifting forwards until it became involved in the head, its edges growing round and encircling the mouth. It will be seen in the section on Development that this process is actually indi cated in the embryo, so that on this, as well as other grounds, we may regard the current view as to how the cephalopod organization was attained as sub stantially accurate. As to which surface of a cephalopod should be called anterior and which posterior we are on sound mor phological ground if we regard the head and foot as ventral and the mantle-cavity as posterior. Nevertheless in many cephalopods, which move about by swimming, the long axis of the body be comes horizontal, like that of a fish, and the anterior surface might be more appropriately termed "upper" or "dorsal" and the posterior surface "under" or "ventral." The viscera of our typical cephalopod are covered by a dome shaped or elongated sheath of skin, the mantle, which is in close contact with the body anteriorly, but posteriorly is free and encloses the mantle-cavity, into which the gills project and the anus, kidneys and reproductive system open.Below the visceral mass are the head and foot which together continue the main mass of the body. On the posterior side of this head-foot (cephalo-pedal mass) is a muscular tube, the funnel. The circlet of arms encircles the mouth.

The main divergences of structure have already been indicated in the section on classification ; but, for the sake of rendering clear the importance of some of the details which follow, it is necessary to recall two important facts, first that Nautilus with its external coiled shell represents a more primitive and less specialized type than do the Dibranchia, a grade of organization seen in many anatomical features, and sec ondly that the Dibranchia have acquired a more active and vigorous mode of life that has led to certain marked departures in structure and function from the type rep resented by Nautilus and (we may assume) the ammonites. Lastly among the Di branchia themselves certain important habitudinal divergences are established, and hand in hand with these we must note structural and physiological adaptations, e.g., to a life permanently spent in the great depths of the sea, to a permanent floating life or to a more active and aggressive existence near the surface. The details of cephalo pod anatomy and physiology may be studied in any good zoological text-book or in divers special papers and monographs. The fol lowing account attempts to eliminate detail and to present the main structural and physiological features of the class in rela tion to the mode of life of the animals concerned.

External Anatomy and General Organization.—The nautiloids and ammonites were in all probability mainly shallow water animals living near the bottom. They relied for pro tection on a calcareous external shell and their speed of move ment was probably inconsiderable. The modern Nautilus repre sents this mode of life pretty closely. The Dibranchia are, as we have seen, on the whole more active, and swimming or floating has become their characteristic mode of locomotion. Ac cordingly we notice the following features in their external organizations : (i ) The mantle, which in the majority of molluscs and in the Tetrabranchia has a passive role and merely contains the viscera and se cretes the shell, has become involved in the mechanism of locomotion. It has lost or almost entirely lost the rigid shell and has become highly muscular. Its expansion and contraction promote a locomotor water current by drawing water into the mantle cavity and expelling it through the funnel. The rapid ejection of this jet of water en ables the animal to execute rapid retrograde movements. As a means of sealing the mantle-aperture while the locomotor jet is under compression, there is developed an "adhesive apparatus," a cartilaginous stud or ridge on each side of the edge of the mantle and a pair of corresponding sockets on the head into which the studs or ridges fit so that the mantle edge is locked to the head. (2) The funnel in Nautilus is represented merely by two muscular folds which meet in the middle line. In the Dibranchia these folds are completely fused up and form a complete tube. (3) Additional locomotor append ages in the shape of fins are developed from the sides of the mantle. These may become very large and no doubt assist in balancing the animal. (4) In accordance with their active, main ly reptorial mode of life, the circumoral appendages, which are many and feebly developed in Nautilus, are fewer in number in the Dibranchia, but more muscular and provided with suckers which in the Decapoda are furnished with horny, often toothed rims. In certain forms the teeth of the suckers are modified as large and formidable hooks. Two of the arms are specially mod ified in the Decapoda for the capture of prey.

Internal Anatomy.

(i) Internal supporting structures. All the Cephalopoda have an internal cartilaginous covering of the main ganglia of the nervous system. In the Dibranchia this is more complete than it is in Nautilus. It encircles the ganglia and constitutes a kind of skull. Besides this structure the greater mobility of the Dibranchia is secured by other skeletal supports of the muscles which are found at the base of the fins, in the "neck," gills and arms of various forms. (2) Viscera. The ali mentary system of the Cephalopoda consists of a muscular buccal mass furnished with a pair of jaws (mandibles) and a rasping tongue (radula), oesophagus, salivary glands, stomach, coecum, liver and intestine. Efficient mastication is secured by the powerful mandibles and sharp-pointed teeth of the radula. In the Octopoda the oesophagus is expanded to form a crop and in the Cirrata, possibly in relation to the special diet of these mainly deep-sea animals, which seem to feed on bottom debris, the radula is frequently degenerate or absent and there is a "second stomach," a capacious dilatation of the intestine. In the Dibranchia the pancreatic element of the liver is partly separated from the latter. Nearly all the members of this subclass have a diverticulum of the intestine situ ated near the anus in which is secreted a dark fluid ("sepia" or "ink"). This can be forcibly discharged, and the dark cloud thus formed in the water serves as a means of escape from enemies. (See section Natural History.) This so-called ink-sac is absent in Nautilus and in certain deep sea Octopoda.

Circulatory and Respiratory System.

These systems are very highly developed in the Cephalopoda. Unlike the rest of the Mollusca the blood is conveyed to and from the tissues in vessels instead of mainly through a system of diffuse cavities (lacunae), though the vascular system of Nautilus is partly lacunar. The process of circulation and oxygenation is more con centrated in the Dibranchia, which have only two cardiac auricles and two gills instead of four auricles and four gills as in Nautilus. The mechanism of respiration is likewise more efficient in the Dibranchia, the rhythmical con tractions and expansion of the mantle musculature procuring a very effective circulation of water over the gills. The latter are feather-like in general plan, i.e., they consist of a central axis with side-branches disposed down each side of it. There are as many as 40 filaments a side in some Di branchia ; but in the Octopoda they are less numerous, and in abyssal forms (e.g., the Cirroteuthidae) they are very much re duced in number and length.

Renal Organs.

The excretion of nitrogenous waste is carried out exclusively by the kidneys; the liver, which in certain other molluscs has an excretory as well as digestive role, does not par ticipate in this function. There are four kidneys in Nautilus and two in the Dibranchia.

Nervous System.

The chief ganglionic centres of the Ceph alopoda are concentrated in the head and are very closely approximated. Such intimate union is not usually found in other molluscs, but is nevertheless seen in certain Gastropoda. This condensation of the central ous system is seen in Nautilus and is carried still further in tain Dibranchia. Features ative of functional specialization are found in the latter, e.g., in some of the Teuthoidea the bral centres are subdivided and the pedal ganglia are likewise vided into brachial and epipodial elements which innervate the arms and funnel respectively. The sense-organs of the Cephalopoda are eyes, rhinophores (olfactory organs), statocysts (organs for the nervous regulation of balance) and tactile structures. The eyes of Nautilus are of a more prim itive construction than those of the Dibranchia in that they have no retractive lens and the optic cavity is open to the exterior.In the Dibranchia the eyes are very complex and approach those of the Vertebrata in efficiency.

Reproductive System.

The sexes are separate in the Ceph alopoda. No instances of hermaphroditism or of sex-change such as are found in other molluscs have so far been reported in this class. Sexual dimorphism is of fairly regular occurrence ; but it is usually expressed in slight differences of size and the propor tion of various parts. In the pelagic Argonautidae (Octopoda) the male is very much smaller than the female, and in the cuttle fish (Doratosepion confusa) the males are distinguished by the possession of long tail-like prolongations of the fins. In nearly all cephalopods the males are in addition distinguished by the modification of one or more of the appendages as an organ of copulation. The male reproductive system is on the whole a little more complex than the fe male, chiefly in relation to the method of copulation. The sper matozoa are transferred by the male to the female in long tubes (spermatophores) which are formed in a special sac (Need ham's organ) on the course of the male vas de f erens. These tubes are deposited either in the neigh bourhood of the mouth of the female (Nautilus; Sepia, Loligo and other Teuthoidea) or in the mantle-cavity (Octopoda ; cer tain Teuthoidea) by means of the copulatory organ (hectocotylus [Dibranchia] : spadix [Nautilus] ). The latter is a simple spoon like modification of one of the arms in the Octopoda. In the Decapoda a great diversity of modifications is found which may involve more than one arm. Similarly in Nautilus an accessory copulatory organ (antispadix) is found. It has recently been suggested that some of the peculiar modifications found in the Decapoda enable the copulatory arm or arms to be used as an organ of stimulation.

Colour Change and Luminescence.

Besides the permanent colour of the skin, the Dibranchia possess a cutaneous system of contractile cells (chromatophores) containing pigment which can be expanded or contracted so as to exhibit or conceal the pigment either of all the cells simultaneously or only of those containing a certain pigment. The circumstances in which these changes are brought about are discussed in the section on Natural History.In certain Decapoda, principally those which live at great depths, special light-organs are developed in various regions of the mantle, arms and head. These organs are not found in Nautilus and the Octopoda (except in Melanoteuthis lucens).

They are only sparsely found in the littoral Sepiidae and Loliginidae; but a special type of light-organ said to produce the peculiar phenomenon of "bacterial light" has been described in certain species of Sepiola and Loligo (Meyer : Pierantoni : Rob son) .

Development.

The development of Nautilus is unfortunate ly not yet known, so that if any clues to the phylogeny of the cephalopods may be obtainable from the embryology of their most primitive living representative, they are still withheld from us. The eggs of all cephalopods are provided with a remarkable amount of yolk so that, unlike that of the rest of the Mollusca, the segmentation is incomplete and restricted to one end of the egg. The embryo is likewise localized at that end and the ectoderm appears stretched out over one extremity of a large mass of yolk. Later on, a sheet of cells is developed below the ectoderm, commencing from that edge of the ectoderm at which the anus is subsequently developed ; and after this, cells migrating inwards from the ectoderm give rise to the mesendoderm. The develop ment of the various organs need not occupy us; but it is necessary to point out that the mouth in the early stage of development is not surrounded by the arm-rudi ments. The latter arise as out growths of the lateral and pos terior edges of the primordial embryonic area. These out growths pass forwards during later development until they reach and encircle the mouth.The funnel arises as a paired out growth of the same area, a con dition which is retained in the adult Nautilus, while in the Dibranchia the two portions fuse together in the median line. The development of the Cephalopoda varies somewhat after the germ layers have been developed, according as to whether there is a yolk-sac or not. The embryo of Sepia, Loligo and Octopus is provided with a yolk-sac which may become partly internal; while in certain Decapoda pre sumed to be archaic there is less yolk and the yolk-sac is prac tically absent ("Egopsid embryo" of Grenacher). Nevertheless, although we may regard the latter mode of development as less specialized than that of the heavily yolked egg, e.g., of Sepia, there is no certain indication in the development of any known cephalopod of those larval phases that characterize the develop ment of other Mollusca. The embryological history of the mem bers of the Cephalopoda reveals as much specialization and differentiation from the more primitive molluscan type of de velopment as does the structure of the adult.

Phylogeny and Evolution.

The structure of the soft parts of fossil cephalopods is only very scantily known, so that our knowledge of the evolution of the class since its first appearance in Cambrian times is largely based on the shell. It thus follows that our main division of the class into Tetrabranchia and Dibranchia.based as it is on the structure of the gills and other primitive traits seen in the visceral anatomy of Nautilus, has little relation to our knowledge of the primitive nauti loids and ammonoids. Similarly our knowledge of the evolution of the Octopoda. in which the shell is vestigial and non-calcified, is rather compromised by the absence of verifiable fossil remains.

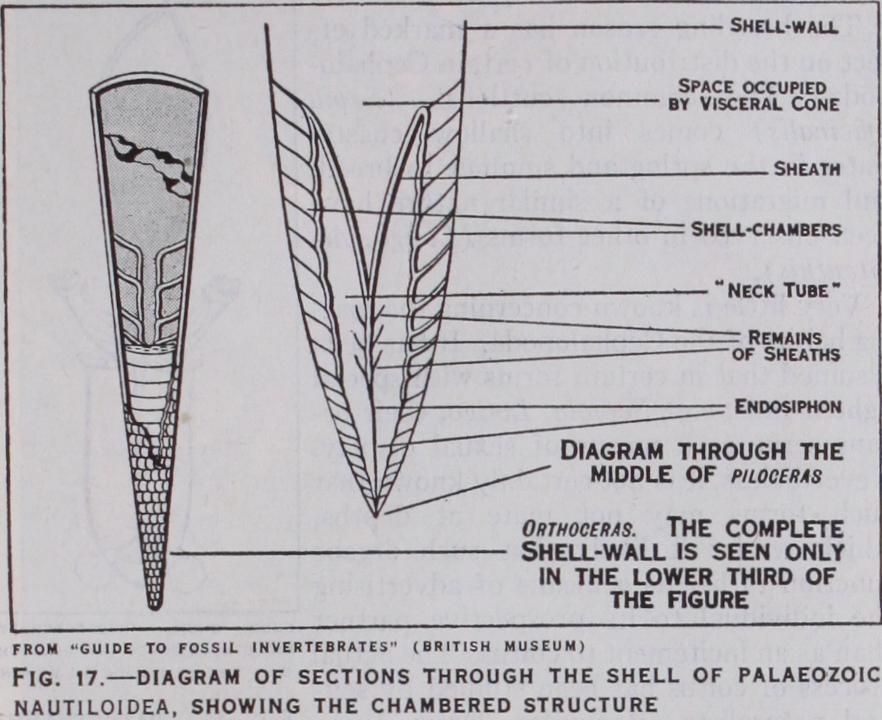

In order to understand the evolutionary history of the Ceph alopoda as revealed by the geological record, it is necessary to allude to the shell of Nautilus, which, by reason of its general or ganization, is regarded as the most primitive living cephalopod. This shell is coiled and subdivided into a number of closed chambers, the last of which is occupied by the animal. Through out the system of chambers runs a median tube, the siphuncle. The earliest forms which we can recognize as cephalopods are found in Cambrian rocks. In Ortlioceras (fig. i 7) we see the unmis takable chambered shell and median siphuncle of the nautiloid.

The shell is, however, straight, not coiled. At a later stage we find the shell becoming coiled like that of a true Nautilus. This is well seen in the Silurian Ophidioceras. In Triassic rocks are found re mains closely resembling our modern Nautilus; but the latter did not actually appear until the early Tertiary.

This short sketch gives us a clue to the first stage in the evo lution of the Cephalopoda. If we accept the view that the Mollus ca are a homogeneous group, it is reasonable to suppose that the primitive Mollusca from which the Cephalopoda sprang were provided with a simple cap-like shell not unlike that of a limpet.

What circumstances of adapta tion or internal momentum dic tated the lines on which cephalo pod evolution should proceed are not known; but the first result was an elongation of the shell achieved by the deposition of lime salts around the edge of the primitive cap-like shell as the animal progressively shifted its position away from the apex. At each successive growth-period the back of the visceral mass se creted a partition (septum), thus forming the successive compart ments of the nautiloid shell. The elongate shell thus produced, which we see in Orthoceras, no doubt became unmanageable and liable to injury. As in the case of the Gastropoda, it became coiled, which had the mechanical advantage of saving the shell from accident and making it more manageable. The second order of tetrabranchs, the ammonites, which are only known from fossil forms, was a very large group and the plentiful remains of their shells at certain horizons has provided material for special studies of evolutionary phenomena at once fascinating and baffling. The ammonites are ranked as Tetrabranchia on conchological grounds; but we do not know in fact whether they possessed the anatomical structure of the nautiloids. They differed essentially from the true nautiloids in having a marginal siphon and a persistent embryonic whorl at the apex of the shell (protoconch). It is customary to derive them from Devonian forms with straight shells, such as Bactrites, though in fact Bactrites itself has certain nautiloid traits. Coiled ammonites appear in the upper Devonian (Goniatites), and there a fter follow a great variety of forms. They are distinguished by tendencies towards uncoiling and great complexity of the sutures (line of junction between the septa and the main shell-wall) which illustrate re markable phenomena of growth (mostly modifications of the principle of Recapitu lation).. Some lineages (or evolutionary strains) illustrate retrogressive evolution, the later members of such series reacquir ing traits seen in earlier stages of the series. These retrogressive stages are especially noticeable in the Cretaceous period, at the end of which the ammonites became extinct. It is not yet safe to say that this group as a whole ran a straight course through increasing complexity to a climax from which they passed to senescence and ultimate decay. It is tempting to read such a plain evolutionary theme into their story; but it seems more likely that as Swynnerton suggests, they were cut off when still a flourishing group by a great secular "revolution" of climate and earth-change, rather than by the exhaustion of their own evolutionary momentum. The history of the dibranchiate Cepha lopoda is dominated by one main evolutionary theme. Our modern squids, cuttlefish and octopods are distinguished from the nautiloid forms by the possession of an internal and partly degenerate shell. In one form alone (Spirula) the shell is still partly external. The position and state of the shell in the Dibranchia is due to the progressive overgrowth of the shell by the mantle and the formation around the shell of a sec ondary sheath, the various parts of which eventually become larger than the shell itself. The loss of the true shell probably went hand in hand with the gradual acquisition of an active swimming habit, in which the protection of a rigid outer covering was replaced by greater mobility entailing the development of stronger pallial muscles. At the same time the acquisition of a fresh orientation probably entailed a readjustment of the centre of gravity of the animal, the heavy, more or less terminal shell being incompatible with rapid movement in a horizontal position. Of forms which connect the Dibranchia with the Tetrabranchia we have no direct evidence. According to Naef we may distin guish certain orthoceratid nautiloids which show an approach to the oldest Dibranchia; but it is not until Triassic times that we meet in Aulacoceras unmistakable evidence of the modification -of the shell. This tendency is seen at its best in the Belemnites. It consists primarily in the enclosure of the apex of the shell in an external calcified sheath, the guard, and the development of an accessory plate, the pro-ostra cum, at the anterior end of the shell. The forms which exhibit these modifications were un doubtedly dibranchiates, as they possessed the characteristic ink sac and hooks on their suckers.

The belemnites gave rise to sev eral lines of descent. In one of these the guard is reduced and the original shell (phragmocone) is coiled (Spirvlirostra). Further reduction of the guard and more extensive coiling of the phrag mocone produced the shell of the modern Spirula. In another line the guard is similarly reduced, and the extension of the phrag moconal septa as closely set and numerous layers up the surface of the pro-ostracum led through the Belosepia to the modern cuttlefish. The modern Teuthoidea (Loliginidae and "Egopsida") are distinguished by the loss of phragmocone and guard and the persistence of the pro-ostracum as a horny "pen." These forms appear in the Jurassic and are probably developed from belemnite-like ancestors. Of living Teuthoidea Ommastrephes preserves a trace of the phragmocone.

Owing to the great reduction of the shell in living Octopoda, in which it persists as fine cartilaginous "stylets" or as somewhat better-developed fin-supports (Cirrata), the stylets, or fin-sup ports, are usually regarded as vestiges of the shell ; but it is pos sible that this interpretation is wrong. We have no knowledge of the ancestry of this group. The structure of Paleoctopus new boldi from the Cretaceous of Syria afford no clue to the early stages of octopod evolution. This form combines cirromorph and octopod characters ; but in eral it appears to be more pus-like. Of the modern poda it is likely that the Cirrata, in spite of much specialization in relation to the abyssal habit, are an older group than the true octopods. As far as the rudiment of the shell is concerned such forms as Cirroteuthis mulleri and T'ampyroteutliis are more tive than Octopus, Eledone and the Argonautidae.

Distribution and Natural History.—The Cephalopoda are exclusively marine animals. No authentic records are available of their occupation of fresh or brackish water. Although they are occasionally carried into estu aries, they do not tolerate water of reduced salinity. In this re spect they are comparable with the Amphineura and Scaphopoda among other Mollusca and with the Echinoderma and Brachio poda. It is interesting, but rather fruitless to speculate as to why so highly organized and dominant a group has never, as far as we know, accommodated itself to fresh water. The fact that there are many littoral species further emphasizes this exclusiveness.

One record is known to the author of an octopod being found living at the mouth of a fresh water stream (Hoyle, go7), and it is interesting to note that certain species have penetrated into those areas of the Suez canal which have a higher salinity than that of normal sea water. No differences have so far been re corded in the numerical frequency of the cephalopods of those parts of the ocean which have a relatively low salinity (e.g., under 34 per mille, as in Arctic and Antarctic waters), and those with an average or high salinity (35 per mille and upwards). In areas of extremely low salinity, such as the Baltic sea, cephalopods are very sparsely represented.

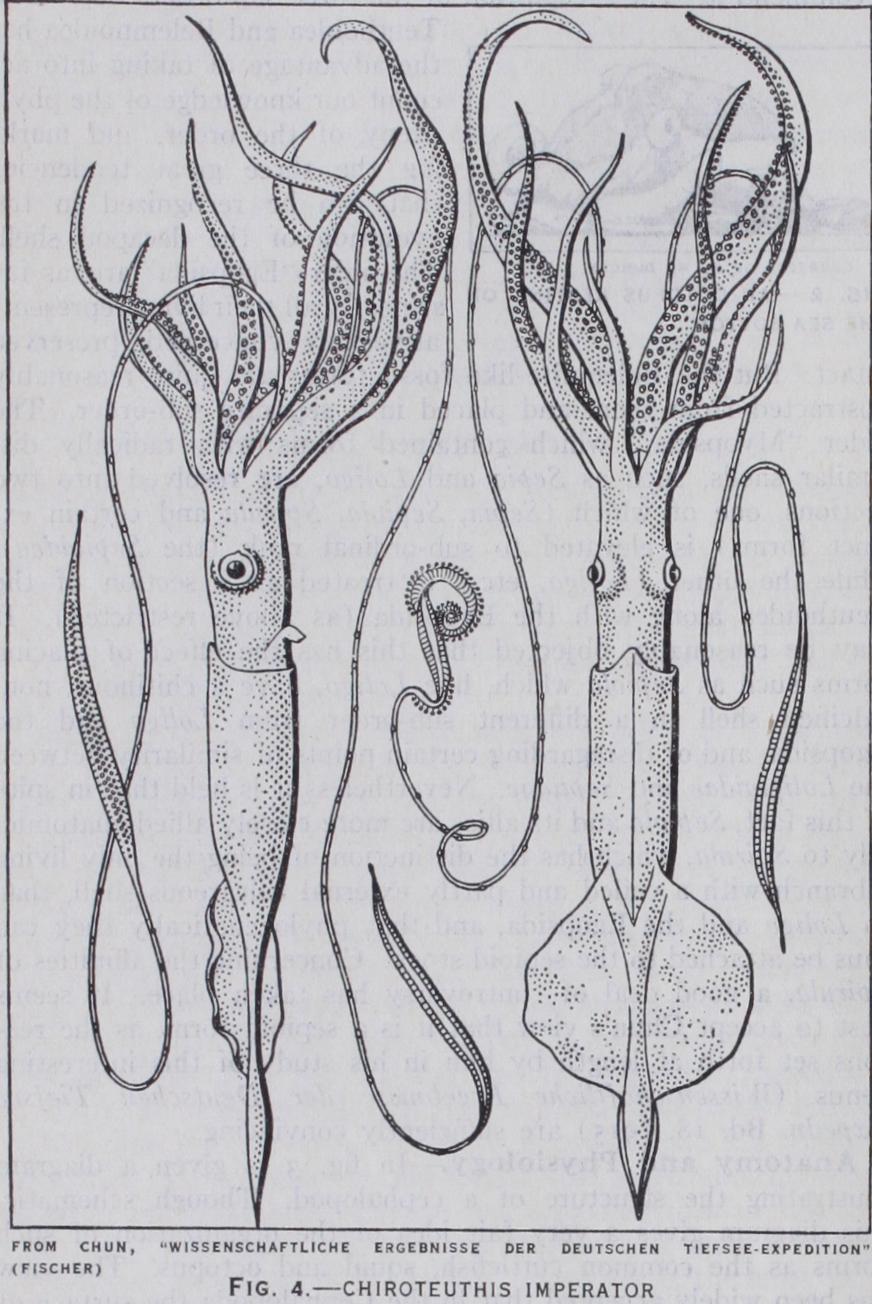

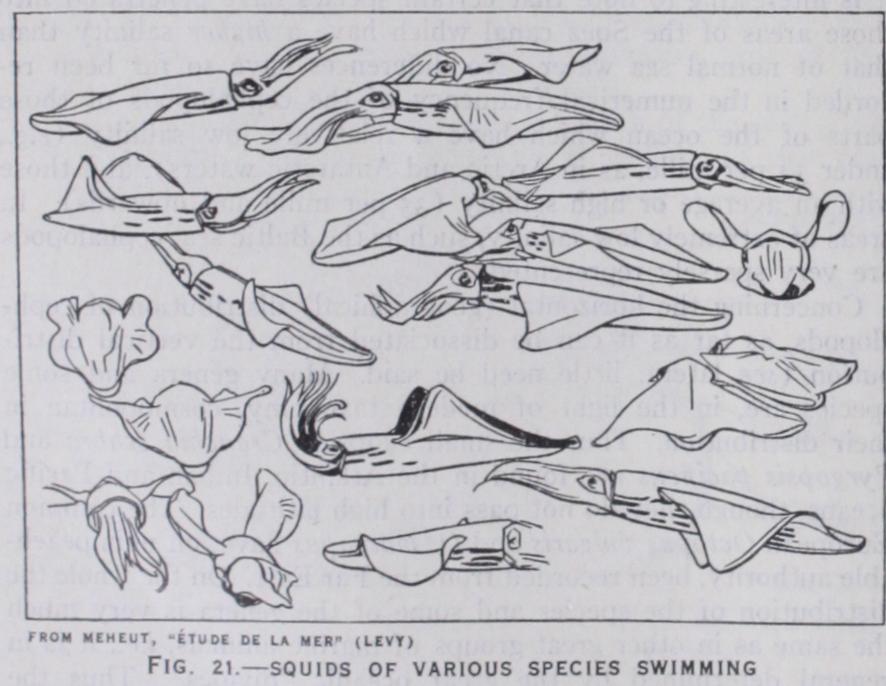

Concerning the horizontal (geographical) distribution of ceph alopods, as far as it can be dissociated from the vertical distri bution (see later), little need be said. Many genera and some species are, in the light of modern taxonomy, cosmopolitan in their distribution. Thus the small egopsids Cranc/iia scabra and Pyrgopsis pacificus are found in the Atlantic, Indian and Pacific oceans, though they do not pass into high latitudes. The common European Octopus vulgaris and 0. macropus have, on unimpeach able authority, been recorded from the Far East. On the whole the distribution of the species and some of the genera is very much the same as in other great groups of marine animals, i.e., it is in general determined by the great oceanic "divides." Thus the Canaries current cuts off a north-east Atlantic fauna from an equatorial and south Atlantic one at about latitude i8°N., and the great "divide" off Cape Agulhas (South Africa) separates Atlantic and Indo-Pacific faunas. Nevertheless, these barriers (due to marked changes in salinity and temperature) seem to be by no means rigid in their effects. Several Mediterranean species are found in the south Atlantic and certain species are common to the Atlantic and Indo-Pacific regions; so that the species can only be grouped into faunas in a very broad fashion. Other quali fications have also to be made. In the first place it is very likely that many species which occur at the surface, e.g., in the cold Benguela current of the south-east Atlantic may be found in deeper water in the Indian ocean, so that the Agulhas "divide" may be only effective at the surface and have a limiting effect only on those Cephalopoda which cannot descend to great depths. Secondly, the identification of species from contrasted areas should depend on a very exact taxonomy, and this is not always easy in practice, as the condition and number of specimens col lected is not always satisfactory. It will be convenient to consider vertical distribution at the same time as the general mode of life of these animals. Nautilus seems to keep near the bottom in the neighbourhood of islands and reefs and has been obtained at a depth of 30o fathoms. It comes into shallow water quite fre quently; but Dr. A. Willey be lieves it breeds in very deep water. The larger Decapoda spend their life swimming at various depths. Some are strictly littoral such as Sepia and Loligo. Most of the Teuthoidea are pela gic, i.e., they live in the open sea far from land, and some of them have a very considerable vertical distribution. Chiroteuthis lacertosa has been taken at a depth of 2,949 fathoms.

In the adult stage the small and fragile Cranchias (Egopsida consuta) are to be reckoned as planktonic organisms, i.e., floating more or less at the mercy of currents rather than swimming with or against the latter. The Octopoda mainly dwell on or near the bottom either crawling on the latter or swimming a short distance off it. Some of them, however, e.g., Eledonella and Cirroteuthis, are not confined to the bottom and are found in mid-water at very considerable depths. Although the large family of the Octo podidae mainly inhabits shallow water, the Octopoda as a whole contain a very large nucleus of deep water forms (one species of Eledonella has been taken in 2,900 fathoms), which display well marked adaptations to life in abyssal conditions.

Alcide d'Orbigny in his account of the Mollusca of South America, asserted that the Cephalopoda are in general "sociable," i.e., gregarious, and this statement is certainly true of Nautilus which were always found together in droves by the native divers employed by Dr. A. Willey, who observed its habits in New Guinea, etc. Nevertheless, Jatta, who made a special study of the Mediterranean forms, was of the opinion that only certain pelagic forms are thus gregarious (e.g., Todarodes, Ocythoe). We should avoid concluding that the coincidence of a large num ber of individuals necessarily implies either a sociable instinct or a desire for the protection afforded by a community, as it may be due to the accidental coincidence of large numbers of indi viduals ("population maximum") in somewhat restricted breeding or feeding grounds. Nevertheless, Verrill has adduced evidence that the shoaling of young Loligo pealei off the coast of New England is not thus accidental.

The breeding season has a marked ef fect on the distribution of certain Cephalo poda. The common cuttlefish (Sepia officinalis) comes into shallow coastal water in the spring and summer to breed, and migrations of a similar nature have been observed in other forms (Loligo, Al loteuthis).

Very little is known concerning the mat ing habits of the Cephalopoda. It has been assumed that in certain forms with special light organs, e.g., Sepiola, Loligo, their or gans serve as a means of sexual display. Nevertheless, it is not certainly known that such forms may not mate at depths, which render it likely that such organs function rather as a means of advertising the individual to its prospective partner than as an incitement to coitus. The actual process of coitus has been studied by sev eral naturalists (Racovitza, Drew, Levy, etc.) ; but, while we know the general lines on which it takes place, the details and particularly those relating to the use of the hectocotylus are not very well known (see Reproductive System). Nor again are we informed as to the bionomic significance of some of the more remarkable cases of sexual dimorphism among these animals, e.g., of the highly elongate and fringed arms of Sepia bur nupi and lorigera (Massy, Wiilker) and the still more remarkable dimorphism in Dor atosepion con f usa (Massy and Robson, Robson and Carleton).

The eggs of most of the Cephalopoda, of which we know the teproductive habits, are laid inshore, and are usually fastened down singly or in clusters on bottom debris such as fragments of coral, stems of plants, etc. Less is known concerning the egg laying of pelagic species, except in special instances such as that of Argonauta, in which a brood chamber is developed in the shape of a shell (not homologous with the true shell) which is secreted by the dorsal arms of the female. Brooding over the eggs seems to take place on the part of the fe male in certain forms (e.g., Octopus vul garis). Little is known concerning the re lations between the sexes apart from those immediately concerned with reproduction. Grimpe, however, records that in cap tivity Sepia officinalis is strictly monog amous though capable of reproduction.

The majority of living Cephalopoda are carnivorous and live principally on Crustacea. Small fishes and other molluscs, how ever, often form part of their diet and there is some evidence that in nature certain species are cannibals. In the Channel Isles Octopus vulgaris partly subsists on the ormer (Haliotis) and has been made responsible (though on insufficient evidence) for a marked decrease in the numbers of that mollusc. The Cirrata whose reduced musculature and radula indicate a loss of activity and of masticatory power probably feed on bottom-debris or minute plankton. The latter in the shape of copepods, pteropods, etc., are probably the food of the smaller pelagic Decapoda. The Cephalopoda are in their turn preyed upon by whales, porpoises, dolphins, seals and sea-birds. The stomachs of whales are often found to contain fragments of Cephalopoda (mandibles and sucker-rings), and it is held that the wax-like substance known as ambergris, which is used in perfumery and is found floating at sea or drifted ashore, is composed largely of cephalopod tissue voided by whales. It is not to be doubted that large squids main tain a desperate struggle with any whale that may attack them, as specimens of the latter are sometimes taken with the marks of sucker-rings imprinted in their skin.

The colour-changes produced in the skin of most cephalopods by the contraction and expansion of the chromatophores have been variously interpreted as affording protective or obliterative colouration or as an expression of certain emotions. It is likely that both these effects are secured by this means. The common octopus has been observed to assume a very close mimetic re semblance to the colour of its background. On the other hand the present author has made observations on colour changes in Sepiola atlantica which are the reverse of protective, as judged by the human eye. The chief means of avoiding capture is, how ever, provided by the "ink" which is expelled from the ink-sac when the animal is attacked. It was originally thought that the ink formed a kind of "smoke-screen" behind or in which the ani mal was hidden from its enemy. Recent observations, however, tend to suggest that the jet of ink, when shot out, remains as a definitely shaped object in the water and serves as a "dummy" to engage the attention of the enemy, while the cephalopod chang ing its colour, so that it is almost transparent, darts off in another direction. Whether this explanation is applicable to all cases is uncertain; and in any case it is uncertain why, if many cephal opods can assume something approaching protective transparency, it should be necessary to add to the means of concealment. The matter is plainly in need of further investigation. The Cephal opoda as a whole are not distinguished by individual eccentricities of behaviour. It is worth while, however, to mention three inter esting cases. (I) Many pelagic squids and cuttles keep very near the surface when swimming, and one of them, "the flying squid," Ommastrephes bartrami, often shoots out of the water in rough weather and has been several times carried by its leaps on to the decks of ships. (2) The male of the pelagic octopod Ocythoe is often found inhabiting the discarded test of the Tuni cate Salpa, a habit in which it resembles the Crustacean Phro nirna. (3) Sasaki has described a very remarkable habit and structural modification in the small cuttlefish Idiosepius pygmeus. The latter, which is found in Japanese waters, is often found ad hering to sea-weeds by means of a rudimentary sucker developed in the dorsal region of the mantle. No instances of parasitism, and only one doubtful case of commensalism have been recorded among these animals.

Economic Uses.—The Cephalopoda are of considerable value to man, principally as a direct source of food. They also consti tute a large part of the diet of certain animals, such as whales and seals, which are of economic importance and in certain parts of the world they are regularly caught on a large scale as bait for certain valuable food-fishes. Squids, cuttlefishes and octopods are eaten by man in many parts of the world. Information con cerning the people who regularly eat these animals is by no means complete as yet. The "Anglo Saxon" people (possibly the Nor dic race generally) do not as a rule eat them, even when a regu lar supply is available. They are largely consumed by south Euro pean (Mediterranean) peoples and in India, Indo-China, Ma laysia, China, Japan and the Pacific islands. Concerning the littoral natives of Africa and central South America no certain informa tion is available. In the Mediterranean region cephalopods have been eaten since early times. They are at present almost invariably cooked for the table; but in the East, e.g., Indo-China and south India, they are also sun-dried for human consumption. In Japan the squid fishery attains a very great importance and in one year over 70,000,000 kilos of squid were landed (Imperial Japanese Government statistics) . Ommastrephes sloanei is the chief form taken in these fisheries. The bait fisheries of south India are a very important local activity and in North America the cod-fishermen rely very largely on various squids for baiting their lines. The only other important material ob tained from cephalopods is "cut tle bone" (the internal shell of the Sepiidae). The uses of this article are described in the arti cle CUTTLEFISH. Among prim itive peoples and in ancient times in Europe various parts of cepha lopods have been used in magical operations and in medicine. Cut tle bone has been used as a rem edy for leprosy and for various disorders of the heart.

Historical.

The study of the Cephalopoda was initiated by Aristotle who devoted much at tention to the group. The modern investigation of their morphology may be dated from Cuvier who gave them the name by which they are now known. H. de Blainville (1777-1850) and Alcide d'Orbigny (1802-57) laid the foundation of the systematic study of the group, the great mono graph Memoire sur les Ceplialopodes Acetabuliferes of d'Orbigny being a landmark in systematic zoology. This work includes descriptions of fossil forms as well as of living species. R. Owen contributed substantially to our knowledge of the morphology of the class, particularly by his Memoir on the Pearly Nautilus (1832). A. Kolliker may be said to have founded the embryo logical study of cephalopods (1843) and Alpheus Hyatt (1 868) led the way in early palaeontological studies of these animals. The rarer pelagic and deep sea forms were only obtained slowly and, although the Cirrata were known as early as 1836 (Eschricht), it was not until towards the end of the last century that the "Challenger" expedition and the researches of W. Hoyle and A. E. Verrill obtained the first substantial contribution to our knowl edge of these forms. Since then, C. Chun, I. Steenstrop, A.Appelob, G. Pfeffer, L. Joubin, A. Naef, S. S. Berry, G. Grimpe, M. Sasaki and A. Massy have contributed to our knowledge of the living forms, while L. Branco, J. Foord and G. C. Crick, S.

Buckman and R. Abel have or ganized the study of fossil forms.

Particular mention must be made of the work of Naef, who in recent years has subjected the living and fossil forms to a syn thetic treatment. Apart from our lack of information concerning the development of Nautilus there still remains much work to be done, particularly on the habits and ecological relationships of these animals, and it is to be doubted whether we are yet in pos session of a sound systematic arrangement of the Decapoda.