Cetacea

CETACEA, an order of mammals (from the Gr. KfTOS, a whale), divisible into three suborders :—Archaeoceti, exclusively fossil ; Mystacoceti, whalebone whales ; and Odontoceti, toothed whales, comprising sperm whales, bottle-nosed whales and dol phins. The term "whale" does not indicate a natural division of the order, and it is used here to mean any member of the Cetacea, irrespective of size. The lengths of these animals are mostly be tween 4 and ioo feet. Their ancestors were probably land mam mals, whose structure has been modified in many respects to adapt them for life in the water, from birth to death. Whales are warm-blooded, breathing air by lungs, without scales in their skin, with hands of the 5-fingered type, with skeleton, brain, heart and blood-vessels mammalian in structure, reproducing like other mammals and nourishing their young with milk ; in all these re spects differing essentially from fishes, to which they have a merely superficial resemblance. Certain species swim habitually in large schools. A few live entirely in fresh water. The majority are marine, some frequenting the coasts, but others oceanic, rarely approaching land. Many undertake extensive migrations and have a wide distribution. Whales have been known to follow a ship for several consecutive days, and Racovitza has used this as an argument for the view that they do not sleep.

External Form

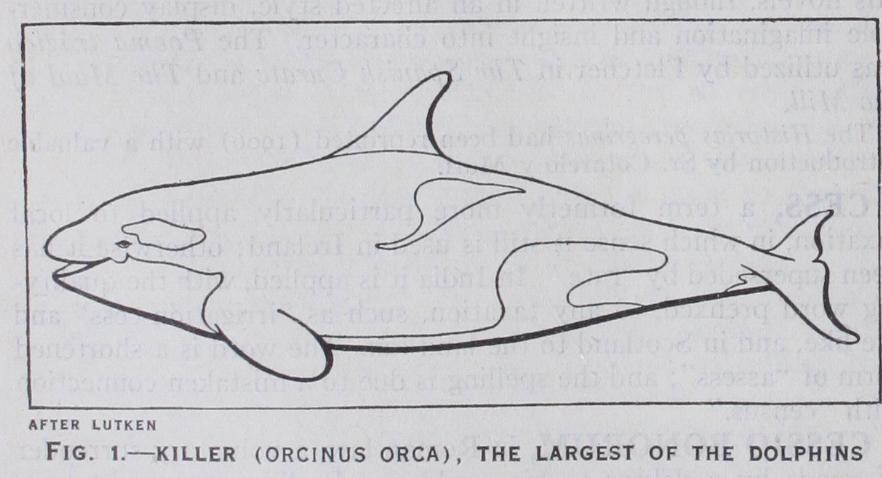

(fig. i.).—Whales swim mainly by the tail, which is produced into two horizontal flukes, not supported by any part of the skeleton, and are thus easily distinguished from fishes, in which the tail is vertical. A dorsal fin, similarly without skeleton, is generally present. The mouth has immovable lips. The fore limbs (flippers) have the form of paddles, and are used principally for maintaining the balance of the body and for steer ing. External hind limbs are wanting. The neck is short and rarely distinguishable in the living animal. The nostrils (blow holes) have been shifted to the upper side of the head, at some distance from the tip of the snout or beak. The part in front of the blow-hole may resemble a forehead, but it really belongs to the beak. Eyes are well developed, but there are no external ears and the outer opening of the ear is minute- The skin is smooth, hairs being usually absent in the adult, except as occasional ves tiges. The vent is at the root of the tail, behind the reproductive opening, on either side of which, in the female, is a groove con taining a teat. The umbilicus (navel) is often visible farther forwards, especially in young individuals.

Other Distinguishing Characters.

The brain-case is short and lofty; the nasal canals pass nearly vertically downwards in front of it, and the facial part is prolonged horizontally forwards as a rostrum. The auditory bones are highly modified; the tym panics are shell-like and loosely attached to the skull. The neck vertebrae are of the typical mammalian number (7), short, of ten fusing with one another; the second, if free, has no prominent odontoid process, the structure on which the head turns in other mammals. The lumbar and caudal vertebrae are freely movable, the interlocking processes of their upper arches disappearing from the thorax backwards. The ribs are very movable on the vertebrae and sternum (breast-bone). The clavicles (collar-bones) are wanting. The flippers show no external division into hand, fore arm and upper arm, and are without definite joints at the elbow and wrist. They contain the typical mammalian bones, but the finger-joints (phalanges) are more numerous in some of the digits than in other mammals. Digits are 5 or 4 without nails. The pelvis is represented by a small curved bone on each side, em bedded in the flesh near the reproductive opening; it does not ar ticulate with the vertebral column, which has no fused sacral vertebrae. In right whales and the sperm whale each half may carry a small bony or cartilaginous vestigial hind limb. The brain is large, its cerebral hemispheres much convoluted. 01 factory organs are almost absent, the nasal passages being func tionally continuous with the larynx. The diaphragm is very ob lique, the stomach has several distinct chambers. The main arteries and veins break up into plexuses of vessels known as retia mirabilia. The kidneys are lobulated. The male organ is usually completely retracted, thus not interrupting the smooth contour of the body. The testes are within the abdomen, the uterus bicornuate, the placenta diffuse.

Respiration.

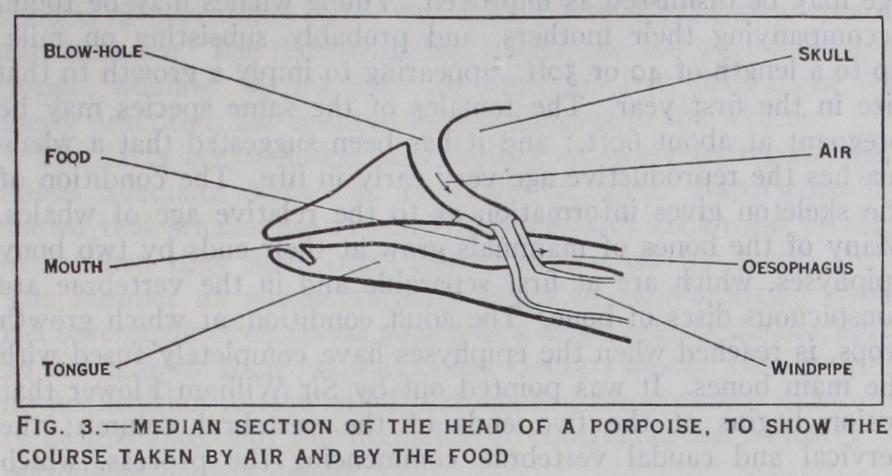

A large whale usually rises to breathe every 5 10 minutes, but the interval may be at least 45 minutes. The blow holes (fig. 2) are either two longitudinal slits (whalebone whales) or a single cres centic slit (toothed whales). On reaching the surface, the whale exposes and opens its nostrils, which are closed during submerg ence, and discharges the exhausted air from its lungs. This is done with considerable force, often producing an audible sound, and the animal is said to blow. The moist air projected upwards is visible from a long distance, in the case of the larger whales, as a column containing particles of condensed water (the spout) formerly regarded as a fountain of water ejected from the head. Expiration is followed immediately by inspiration, and the whale then sinks horizontally. It repeats these actions several times, rising to the surface on each occasion with out exposing much more than the part of its head which carries the blow-holes. When it has thus thoroughly changed the air in its lungs, it rises in a different manner. The back is strongly arched and much of it becomes visible. The back fin, if present, appears to be situated on a rotating wheel, rising from behind, reaching the summit of the arched back and descending into the water in front. The whale then leaves the surface and is said to sound. The maximum depth of its dive has been supposed to be at least loo fathoms. The right whales, humpback and sperm whale (but not the rorquals) usually throw their tails above the surface as they sound ; and at other times, like many of the dolphins, they leap completely clear of the water. Differences in these respects, and in the form and direction of the spout, enable whalers to distinguish species.The horizontal position of the tail-flukes facilitates rising to the surface and returning to the depths, movements of vital impor tance to the Cetacea. Another effective adaptation to aquatic life is the course taken by the air in passing to the lungs. The larynx and epiglottis form a tube passing through the pharynx into the lower end of the nasal passages (fig. 3). Here it is grasped by the soft palate, and the blow-holes thus become continuous with the windpipe and lungs, the mouth being used solely for feeding—as in recently born marsupials, but not as in other adult mammals, which can breathe through either the nose or the mouth.

Prolonged submergence involves other demands on the re spiratory organs. The thoracic cavity of the Cetacea is unusually extensible, and thus provides for a corresponding expansion of the lungs, depending on the loose attachments of the ribs and the considerable projection of the oblique diaphragm into the cavity of the contracted thorax. Whales have a larger amount of blood, in proportion to their size, than other mammals, and this involves an increased capacity for carrying oxygen to the tissues by means of haemoglobin, the red colouring matter. The very deep red colour of the muscles seems to imply that these structures also hold a specially large quantity of oxygen. The characteristic retia mirabilia are further adaptations. In the common porpoise, for instance, the upper and lateral parts of the thorax are covered by an elaborate arterial rete mirabile, lying just outside its lining membrane. Branches of this plexus extend upwards into the neural canal of the vertebral column, an arrangement which en sures an adequate supply of oxygen to the spinal cord and brain. Although physiological evidence cannot be quoted, the retia mirabilia probably act as reservoirs, the arterial portions containing a large supply of oxygen, the amount of which may largely influence the duration of submergence. The venous por tions probably hold exhausted blood, which would otherwise cir culate too freely. The principal danger to which a diver is exposed is the liberation of gas-bubbles into his blood, due to diminishing water-pressure, if the ascent to the surface is too rapid. The retia may perhaps have the function of retaining bubbles and of pre venting their access to the general circulation.

Hair.

Whales maintain a constant high temperature, not very different from that of man. A hairy coat has been discarded, as a means of avoiding the loss of heat, in favour of blubber ; but a few vestigial hairs may occur—an unmistakable sign of the origin of Cetacea from land mammals. In Inia numerous scattered hairs occur on the beak. Whalebone whales have hairs, in Rhachian ectes up to 4omm. long, on parts of the head and lower jaw; and in dolphins a few long hairs are found on the beak, before birth.

Skin and Colour.

The outer, horny layer of the epidermis is thin and readily separates from the body after death. The deeper layer is nearly always pigmented, in certain parts, which then appear black, or varying shades of grey, brown or blue. The commonest type of colouration is dark above and white be low, the relative extent of these regions varying with the species, the white area sometimes increasing with age. Many dolphins have a black streak extending from the eye to the flipper, per haps representing the lower limit of the ancestral dark region. Some whales are completely black or white. In certain cases the normal white is replaced by a bright yellow colour. A. G. Ben nett found that in Antarctic rorquals this is due to an external film composed of an enormous number of diatoms. These uni cellular algae were found all over the skin, but were not conspicu ous on the dark parts. In the common porpoise and its allies the skin of the edge of the dorsal fin or flippers bears a series of small, horny tubercles, which have been considered by some authors to indicate an affinity to Edentate mammals, a conclusion not uni versally accepted. The deeper part of the skin (dermis) is usually inconspicuous, but is better developed in the Delphinap teridae. The white whale, belonging to this family, has a thick epidermis and a rather thinner dermis, and its skin has been used commercially as "porpoise leather." Blubber.—This characteristic part of a cetacean is formed of tough fibrous tissue enclosing an enormous amount of oil. It invests every part of the whale, but is thicker in certain regions, for instance near the dorsal fin. In the sperm whale the maximum thickness is as much as i4in., and in the Greenland whale 20 inches. In the latter, according to Scoresby, 4 tuns of blubber, by volume, yield 3 tuns of oil. In a whale of 7o tons the blubber weighs about 3o tons, and 2 tuns of oil may be extracted from each of the gigantic lower lips. The blubber of the rorquals now hunted is thinner, and in the smaller dolphins it does not much exceed one inch. Although specially important in retaining heat, the insulating properties of this layer probably afford protection against an excess of warmth in tropical waters. Blubber is little developed in newly born whales, and perhaps for this reason the parent resorts to warmer water to give birth to her young. It varies in condition at different times, a whale being often lean on its first arrival in polar seas, where the blubber improves in quality owing to the large amount of food found in those waters. The stomachs of whales captured in temperate latitudes are some times empty, and blubber is probably a reserve material which can be drawn on when food is scarce. It may further help mate rially to prevent the crushing of the tissues, during a deep dive, by the enormous pressure of the superjacent water.

Food.

Dolphins typically eat fishes, to which diet they are adapted by their teeth, generally numerous and uniformly conical; but cuttlefish also may be eaten. The stomach of a species of Sotalia has been found to contain vegetable matter. The Killer is exceptional in eating marine mammals and birds, in addition to fishes. The sperm whale and the bottle-nosed whales (Ziphiidae) are mainly dependent on cuttlefish, some of which must be ob tained at considerable depths; but these also take occasional fishes. A diet of cuttlefish is often associated with a reduction of the number of teeth, in certain dolphins, the sperm whale and the Ziphiidae.

Whalebone.

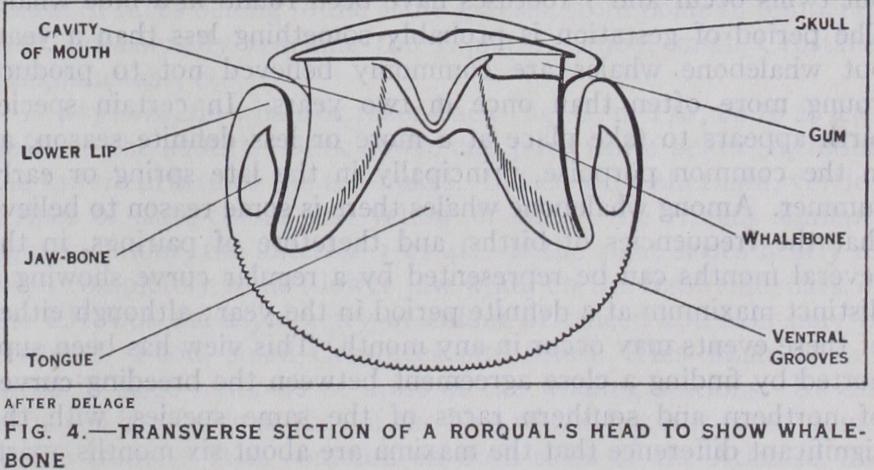

The whalebone whales feed exclusively on plankton (q.v.), including fishes. They obtain food by means of a whalebone sieve, and the adequacy of the method may be esti mated by the fact that two tons of plankton have been taken from the stomach of a blue whale. Plankton is specially abundant in the cold waters of both polar regions, and whales visit them to profit by this plenty.Whalebone or baleen is derived from the skin lining the mouth and has nothing to do with true bone. The sieve is composed of two sides, each running longitudinally along the entire length of the outermost part of the palate, and being continuous with its fellow at the front of the beak. A side consists of as many as 300-400 transversely placed, flexible, and horny blades, embedded at their base in a substance known as the gum, and with a short interval between each two. The blades are longest and widest at the middle of the series and progressively smaller towards both ends, where they become very short. Seen from the front or back, an isolated blade appears roughly triangular (fig. 4), the shortest side embedded in the gum, the outer border straight, and the inner border slightly convex. On the inner aspect of each principal blade is a transverse row of a few very short blades ; and all the blades are produced into long hairlike structures, composed of the same substance as the whalebone itself. Owing to the presence of these hairs, the sieve, seen from its inner side, resembles a door mat or the fleece of a sheep. Between the two sieves lies the tongue, which is of immense size, in contrast with the much smaller tongue of the toothed whales.

The two halves of the lower jaw are greatly arched outwards, the mouth being thus enormous. The blades are bent backwards by the closure of the mouth, recovering a vertical position, by their own elasticity, as it opens. The great lower lip overlaps the outer edges of the blades, and the water must thus escape from the mouth through the chinks between these structures. The whale feeds, after sounding, by swimming through a shoal of plankton with its mouth open. Water enters at the front end; and, before it leaves, the food has been strained off by the hairy fringes of the baleen-plates. The mouth is then closed, the tongue having no doubt helped to force out the water, while licking the food off the sieve. The characters of the baleen afford one of the most convenient ways of distinguishing species of whalebone whales. The blades are longest in the Greenland whale, where they may reach the astonishing length of 15 feet.

Sense-organs.

The olfactory organs are greatly reduced, and it is doubtful whether whales have the sense of smell. The nasal passages, however, are of vital importance, since they serve as the sole method of admitting air to the lungs. The eyes are small, with arrangements for withstanding water-pressure. Scoresby stated that vision is acute in the Greenland whale, which is dull of hearing in the air, but is readily alarmed by even a slight splash ing in the water. The external auditory passage is narrow and opens by a minute hole on the head, not far behind the eye. In whalebone whales it is blocked by a large mass of wax, several inches in length, and it cannot be of much service in hearing. It is believed that vibrations in the water reach the ear through sacs given off by the Eustachian tubes or through the bones and other tissues of the head. The tympanic bones are dense and shell like, well developed and loosely connected with the rest of the skull. There can be little doubt that the auditory organs are of real importance.

Breeding.

The Cetacea are in all respects typically mamma lian in their reproduction. The young is nourished in the uterus by a placenta, and is not born until it has attained a form essentially that of the adult, sometimes exceeding one-third the length of the mother. In the common porpoise the newly born young is about eft. long and in the largest whalebone whales at least 20 feet. A single young is typically produced, but twins occur and 7 foetuses have been found in a blue whale. The period of gestation is probably something less than a year, but whalebone whales are commonly believed not to produce young more often than once in two years. In certain species birth appears to take place at a more or less definite season, as in the common porpoise, principally in the late spring or early summer. Among whalebone whales there is some reason to believe that the frequencies of births, and therefore of pairings, in the several months can be represented by a regular curve showing a distinct maximum at a definite period in the year; although either of these events may occur in any month. This view has been sup ported by finding a close agreement between the breeding curves of northern and southern races of the same species, with the significant difference that the maxima are about six months apart, corresponding with the difference in seasons between the two hemispheres. Tropical species, such as the sperm whale, perhaps have no definite breeding period.

Migrations.

The principal movements of many whales are largely connected with the two functions of feeding and repro duction. The humpback, for instance, appears in large numbers in sub-Antarctic waters in the spring (October) and remains there till the summer. As the season advances it becomes less numer ous, but it is found off the south and west African coasts at the time that would be expected on the assumption that it is moving northwards. At the height of the southern winter it is found even as far north as the equator, and it travels southwards again as the spring returns. It is probable that this species, like others, seeks warmer water in which to bring forth its young and that pairing takes place at about the same time. Its journey to the far south is for the purpose of feeding.

Growth and Age.

Little can be said of the duration of life in whales; and statements that large individuals must be of great age may be dismissed as unproven. Young whales may be found accompanying their mothers, and probably subsisting on milk, up to a length of 40 or Soft., appearing to imply a growth to that size in the first year. The females of the same species may be pregnant at about 6of t. ; and it has been suggested that a whale reaches the reproductive age very early in life. The condition of the skeleton gives information as to the relative age of whales. Many of the bones of mammals grow at their ends by two bony epiphyses, which are at first separable and in the vertebrae are conspicuous discs of bone. The adult condition, at which growth stops, is reached when the epiphyses have completely fused with the main bones. It was pointed out by Sir William Flower that fusion begins at the two ends of the vertebral column ; the cervical and caudal vertebrae commencing the process, which gradually extends from both ends towards the middle. This obviously gives some information as to the relative age of adolescent individuals, but it leaves untouched the question of the duration of life.

Species Hunted.

The whaling industry (q.v.) has been mainly based on about nine species, of which all but the sperm whale are whalebone whales. The Basques hunted the Atlantic right whale (Balaena glacialis) at an early date, and the industry was specially flourishing in the 12th and 13th centuries. The Arctic fishery began about 1611 and was based on the Green land whale (B. mysticetus). The hunting of the sperm whale (Physeter catodon) began about a century later; and the southern right whale (Balaena australis) was captured in large numbers by some of the vessels subsequently engaged in this industry. The Pacific grey whale (Rhac1iianettes glaucus) was taken in considerable numbers, on the coast of California, before the middle of the 19th century. Modern whaling depends mainly on two species of rorqual, the great blue whale (Balaenoptera musculus) and the fin whale (B. physalus) though the Sei whale (B. borealis) is not unimportant in certain localities. The hump back (Megaptera nodosa) has at times been the most important constituent of the catch of modern whalers, who in one or two localities take a few specimens of Bryde's whale (Balaenoptera brydei) . The following, of less importance commercially than the great whales, have also been systematically captured by whalers or fishermen at various times :—the narwhal (Monodon mono ceros), the white whale (Delpiiinapterus leucas), the pilot whale (Globicephala melaena), the bottle-nosed whale (Hyperoodon rostratus), the common porpoise (Phocaena phocaena), and others of the smaller dolphins.History gives a melancholy record of the results of intensive whaling. The Atlantic right whale is no longer to be found on the Biscay coast, and, though it has made some recovery during the last century, it was believed at one time to have become extinct. The southern right whale, once extremely common on the coasts of South Africa and Kerguelen, and in other localities, is occasionally represented in whaling returns by a very few specimens. The Greenland whale disappeared successively from the bays of Spitsbergen, the Greenland sea, Davis straits and the region of Bering straits. There is no indication of the reappear ance of these animals off Spitsbergen or Jan Mayen, where they were formerly present "in immense numbers" ; and, though a few probably linger in some of the old localities, the Greenland trade is dead. The Pacific grey whale was nearly exterminated off the coast of California, and was thought to be extinct. It has recently reappeared in small numbers, and a few are being taken by the Japanese in their own waters. The capture of humpbacks has seriously declined. In 1844 the United States alone had 315 vessels employed in the chase of the sperm whale, but one fishing ground after another had to be abandoned. Sperm whales are still taken at whaling stations, off " the coasts of Natal and the British Isles and in the Straits of Gibraltar, but the large fleets formerly engaged in the chase of these animals have ceased to exist. Of the important species, the blue whale, the fin whale, the humpback, the sei whale and the sperm whale alone survive in considerable numbers; and the disappearance of the first two would involve the extinction of the greater part of the industry. The invention of an improved harpoon-gun in 1865 gave a new impetus to whaling, and this has culminated in the extraordinary success of operations in the dependencies of the Falkland islands and Boss sea. The reintroduction, within the last year or two, of pelagic whaling, by methods far more efficient than those f or merly practised, has resulted in new dangers to the whales. The facts are ominous, and history is likely to repeat itself unless adequate steps can be taken in time. Experience has shown that whales do not readily come back to an old locality, even when they have been free from pursuit for many years. The number of whales recently taken in sub-Antarctic waters has several times exceeded Io,000 in a single season, and in 1925 26 it was more than 7,000 at South Georgia alone. History gives no justification for the belief that whaling can continue indefinite ly at this rate, and the necessity of controlling the industry on reasonable lines is urgent.

Commercial Products.

Whalebone, the most valuable prod uct of the Greenland whale, was at one time worth £2,000 a ton. That of the rorquals is shorter and of inferior quality. Oil is produced by all Cetacea, but the sperm oil of the sperm whale and Ziphioids differs in constitution from the train oil or whale oil of other whales. Spermaceti and ambergris are products of the sperm whale. Guano and other materials are obtained by grinding the dried flesh and bones of large whales. Meat of good quality is available from nearly all Cetacea. The flesh of dolphins was formerly esteemed a delicacy; and it had the advantage, in Roman Catholic countries, of being considered fish which could be eaten on fast days. The common porpoise was formerly hunted on a large scale for its meat. Ivory is obtained from the tusk of the narwhal and from the teeth of the sperm whale. Leather can be prepared from the skin of the white whale.

Suborder 1.

ARCHAEOCETI. The Zeuglodontidae of the Eocene, constituting this group, are believed to have been derived from the Creodontia, the primitive fossil members of the Carniv ora ; but Gregory thinks that they may have descended from In sectivora of the type represented by Pantolestes. Their skull characters are intermediate between those of their supposed an cestors and those of recent Cetacea in the position of the nostrils, the relations of the maxillae and the dentition, which consists of 3 incisors, I canine, 4 premolars, and 3-2 molars on either side of each jaw. The first 4 or 5 teeth are conical and single-rooted, and the other teeth are double-rooted, with serrated crowns. A milk dentition is found.The recent Cetacea have no milk teeth, and there is no differ entiation into incisors, canines and molars. The Squalodontidae (Eocene to Pliocene), included in the Odontoceti, are believed to have descended from the Zeuglodonts and to have given rise to some at least of the recent toothed whales. The origin of the Mystacoceti is uncertain.

Suborder 2.

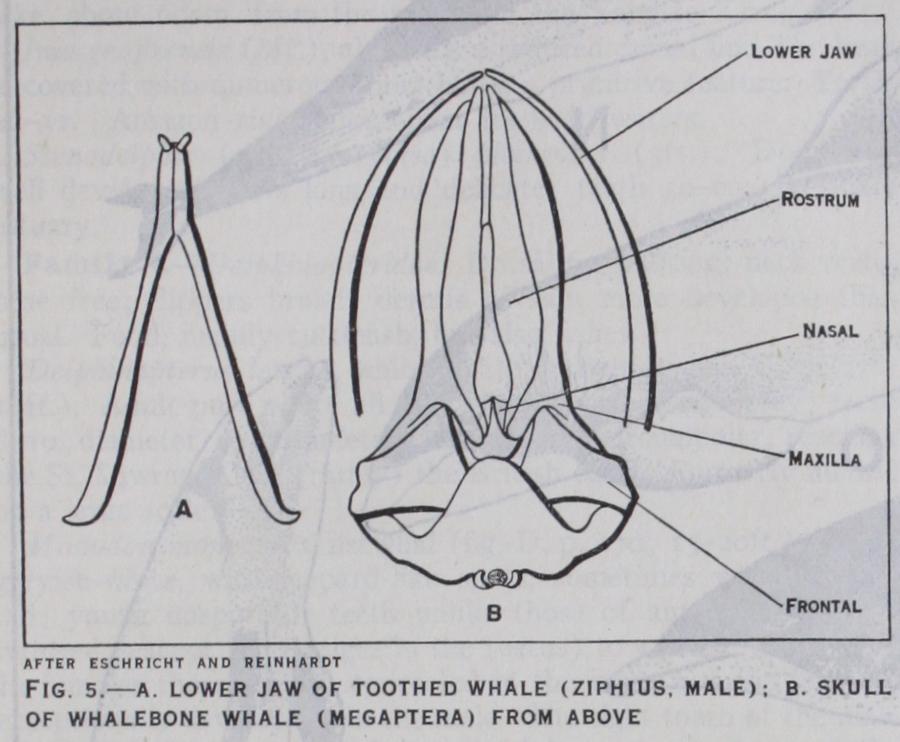

MYSTACOCETI, whalebone whales. Whalebone present ; teeth wanting in the adult, numerous and vestigial in the embryo; lower jaw large, its halves curved outwards (fig. 5, B) and loosely united in front ; blow-holes two longitudinal slits (fig. 2, A) ; skull symmetrical, the nasal bones relatively well de veloped, maxillae not covering the orbital plates of the frontals; first pair of ribs alone joining the sternum, which consists of one piece. The females are slightly larger than the males.

Family

1.—Rhachianectidae, with Rhachinectes glaucus, Pa cific grey whale (fig. L, p. 17o; 45ft.). Head small, less than one quarter the total length; dorsal fin wanting; flippers 4-fingered. R. C. Andrews considers Rhachianectes the most primitive of the Mystacoceti, in view of the occurrence of long hairs scattered over the entire head and lower jaw, the short and relatively few baleen-blades, the free neck-vertebrae, the large pelvis, and other characters. The lower side of the throat region has two or three grooves. Rhachianectes prefers shallow water, swimming even in the surf and occurs in the North Pacific, from California north wards to the Arctic ocean and off Japan and Korea.

Family

2. Balaenidae. Skull much arched ; baleen long and narrow ; ventral grooves wanting ; neck vertebrae fused.Neobalaena marginata, pigmy whale (2of t.) , is doubtfully placed in this family. It differs from the right whales in its small head, about one-fifth the total length, in its less arched rostrum, in having a dorsal fin and in its 4-fingered flippers. It is known from New Zealand and Australia.

Balaena, right whales. Dorsal fin wanting; flippers broad, with 5 fingers; head one-quarter to one-third the total length.

B. mysticetus, Greenland whale (fig. A, p. 1770 ; 6of t.) . Head enormous, one-third the total length; rostrum greatly arched, pro viding room for exceptionally long baleen, up to 15 feet. Arctic, circumpolar, and formerly abundant off Spitsbergen, both sides of Greenland and the North Pacific to Beaufort sea, but reduced by whaling to the verge of extinction.

B. glacialis, Atlantic right whale or Biscay whale (fig. B, p. 170), about the same size, but differing from B. mysticetus in its less arched head, its shorter baleen (up to 9f t.) and the shape of its lower lip. It was formerly common in the Bay of Biscay and it has been recorded from the Mediterranean. It has been hunted, in recent years, off Iceland, Norway and the British Isles. It visits the eastern United States, its northern range in the Atlantic coin ciding nearly with the southern limit of the Greenland whale; but, like other right whales, it avoids the tropics.

B. australis, Southern right whale. Resembling B. glacialis, but found off Australia, Kerguelen and other parts of the southern sea, where 193,522 were killed by American whalers in 1804-1817. A few are still taken off South Georgia, the South Shetlands and the African coasts. The Balaena, hunted in Japan, may be a distinct species.

Family

3.—Balaenopteridae, rorquals and humpback. Ros trum less arched than in Balaenidae, baleen-blades shorter and broader; dorsal fin present; skin covering the throat with nu merous, conspicuous, longitudinal grooves; flippers narrow; neck vertebrae free. At least 90% of the whales now hunted belong to this family.Balaenoptera, rorquals. Body relatively slender; dorsal fin well marked ; flippers small, narrow and pointed.

B. musculus, blue whale or Sibbald's rorqual (fig. F, p. 170; at least 1 oof t.) is the largest of all animals and the most important in the estimation of modern whalers. Colour nearly uniformly bluish-grey above and below, including both surfaces of the tail flukes; baleen jet black, with black fringes. Cosmopolitan, on the assumption that (as in others of the family) the northern and southern races belong to the same species, from polar to temperate seas, occasionally reaching the Equator. Food, small Crustacea (Euphausians, etc.) .

B. physalus, fin whale or razor-back (fig. G, p. 170; up to at least 8of t., in the south) . Dark above and pure white below, including the lower surface of the tail-flukes. Baleen with alternate, vertical stripes of slate-colour and yellow or white, the fringes similarly light in colour, the anterior 3 or Oft. of the right series nearly al ways completely white; lower jaw white on the right side, dark on the left, but the asymmetry of colour of baleen and skin may be reversed. Food, small Crustacea and fishes. This whale is cap tured in large numbers at most of the whaling stations. Its dis tribution is as wide as that of the blue whale, but it is rarely found in the tropics. It is common on both sides of the Atlantic, and it enters the Mediterranean. A few are stranded annually on the British coasts.

B. borealis, sei whale or Rudolphi's rorqual (fig. H, p. 170; 52ft.). White and dark parts not so sharply delimited as in the fin whale ; lower surface of tail-flukes bluish-grey ; baleen black, its fringes white, silky and curling. Temperate parts of all the oceans, not wandering so near the Poles as the two preceding species. Food, Crustacea, less often fishes.

B. brydei, Bryde's whale. Nearly as large as the sei whale, from which it differs in having straight hairs on its baleen-blades. and in its food, which consists principally of fishes. South and West Africa, apparently reaching the West Indies.

B.

acutorostrata, lesser rorqual (fig. I, p. i 7o ; 33 f t.) . Coloration as in the fin whale (without asymmetry of colour) ; a conspicuous white area on the outer side of the flipper. Baleen and its fringes all white or yellowish. Food, largely fishes, but also Crustacea. Temperate and polar latitudes of both hemispheres, including the British and both North American coasts, but not hunted.

Megaptera nodosa, humpback (fig. J, p. 17o; 52ft.). Body thick, dorsal fin evanescent ; flippers enormously long, nearly one third the total length. Colour variable, sometimes nearly all black, but with varying amounts of white in other individuals ; flippers sometimes pure white; baleen and its fringes black. Food, fishes and Crustacea. Cosmopolitan, from the Arctic to the Antarctic ocean, and more frequenting warm water than the rorquals. The humpback was almost the only species hunted at the commence ment of the great Antarctic whaling enterprise, beginning in 19o5, and was almost equally important on the African coasts. The numbers frequenting the whaling localities have greatly dimin ished.

Suborder 3.

ODONTOCETI, toothed whales. Teeth present throughout life ; whalebone wanting ; lower jaw more or less triangular (fig. 5, A), the front part often narrow, the two halves firmly united ; blow hole single (fig. 2, B) ; skull asymmetrical, nasals reduced, maxillae covering the orbi tal plates of the f rontals ; several pairs of ribs joining the sternum, which consists, in the young at least, of several pieces.

Family

1.—Physeteridae, sperm whales. Teeth numerous in lower jaw vestigial or absent in. upper jaw in recent forms.Physeter catodon, sperm whale (fig. C, p. 170 ; 63ft.). Size gigantic ; head im mense, about one-third the total length; snout enormous, truncated, extended be yond the narrow, ventrally situated mouth (fig. 6, A) ; lower teeth 20-26 on each side, of great size, up to 41b. in weight, conical; about 8 pairs of smaller, often malformed, upper teeth ; left nasal passage alone de veloped, the single blow-hole curved, on the upper, left side of the snout, near its front end ; dorsal fin reduced to a low hump, continued as a ridge towards the tail; colour black or brown all over, sometimes marked with white, especially in aged individuals. Male up to 63ft., female not often ex ceeding 35 feet. The sperm whale occurs in all tropical waters, but stragglers, nearly always old males, reach both polar seas.

It is polygamous, a school of females being accompanied by one or two large males. The sperm oil produced by this spe cies is everywhere mixed with spermaceti, most of which is obtained from a receptacle, the case, occupying much of the snout, to the right of the single nasal passage, and capable of containing nearly 5oogal. of mixed oil and spermaceti. The sperm whale dives to a great depth, in pursuit of cuttlefish, its main food, though it also eats fishes. The case is supposed, by its buoyancy, to support the gigantic skull and to facilitate a rapid return to the surface. Ambergris is a morbid concretion of the intestine, commanding a high price.

Kogia, lesser sperm whale (about 'oft.) resembles Physeter in general characters, including the position of the blowhole, the single nasal passage, and the presence of a spermaceti organ ; but the head (fig. 6, B) is relatively much smaller. Lower teeth, about 12 on each side, long, delicate, and curved; upper teeth wanting. Indian ocean and coasts of Australia, and recorded from eastern North America, Brittany and Holland.

Family

2.—Ziphiidae, beaked whales. Allied to the Physeter idae and producing sperm oil, but teeth much more reduced. A pair of longitudinal grooves in the throat region (fig. 9, A–C) . Dorsal fin behind the middle of the body; tail (fig. 7, A) not notched at the junction of the flukes, flip pers small; functional teeth (fig. 8, A, B) 1-2 pairs in the lower jaw, generally below the gum in females ; minute vestiges of teeth may occur in either jaw. Food, cuttlefish. The rostrum becomes consoli dated into a hard, bony mass in Ziphius and Mesoplodon, and these fragments are found in British late Tertiary deposits.Berardius has 2 pairs of large teeth at the front end of the lower jaw (fig. 8, A). B. bairdi (4oft.), North Pacific, is the largest Ziphioid. B. arnuxi, New Zealand, Argentina, not uncommon in Antarctic waters.

Ziphius cavirostris, Cuvier's whale (26f t.) has one pair of teeth at the tip of the lower jaw, much more massive in males (fig. 5, A) than in females, in which they remain beneath the gum. Cos mopolitan, and not uncommon at certain times along the British coasts.

Hyperoodon rostratus, bottle-nosed whale (fig. E, p. 17o; male, 3I f t. ; female, 25ft.). Teeth small, one pair (occasionally two pairs) at the tip of the lower jaw, alike in both sexes, remaining concealed till a late period, but then piercing the gum, at least in old males. Distinguished from Ziphius by a large bony crest on the upper side of each maxilla. With increasing age these crests become immense, in the male, producing a notable alteration in the head, the forehead (fig. 9, B) becoming enormous and trun cated. Common in the North Atlantic, where it has been exten sively hunted to the north of Scotland ; and frequently stranded on the British coasts, though rare in the eastern United States. H. plani f rons, Australia, New Zealand and Argentina.

Mesoplodon (fig. 9, C). Teeth, one pair (fig. 8, B), smaller in females and usually remaining beneath the gum, typically near the angle of the mouth, but in three species at the tip of the jaw. Of these, M. minus has been stranded on the Irish coast; and M. pacificus, described in 1926 from a Queensland skull, appears to be about 25ft.

long, and would therefore be the largest Mesoplodon. M. bidens, Sowerby's whale (I5ft.), has its teeth in the typical position (fig. 8, B) . Up to 1914 nearly half the records were British strandings, the others being from the Baltic to the eastern United States. M. layardi, of South Africa, Aus tralia and New Zealand, has an extraordinary modification of its teeth, which curve over the beak, nearly meeting and preventing the mouth being opened to more than a small extent. Mesoplodon is oceanic, like other Ziphioids; but its species (about ten) appear to have a relatively restricted distribution.

Family

3.—Platanistidae. Inhabiting rivers or estuaries. Neck-vertebrae larger than usual, not fused ; flippers large and broad, with few phalanges. Food, fishes, captured by probing the mud with the long, narrow jaws, which have numerous teeth; as well as Crustacea and probably other small animals.

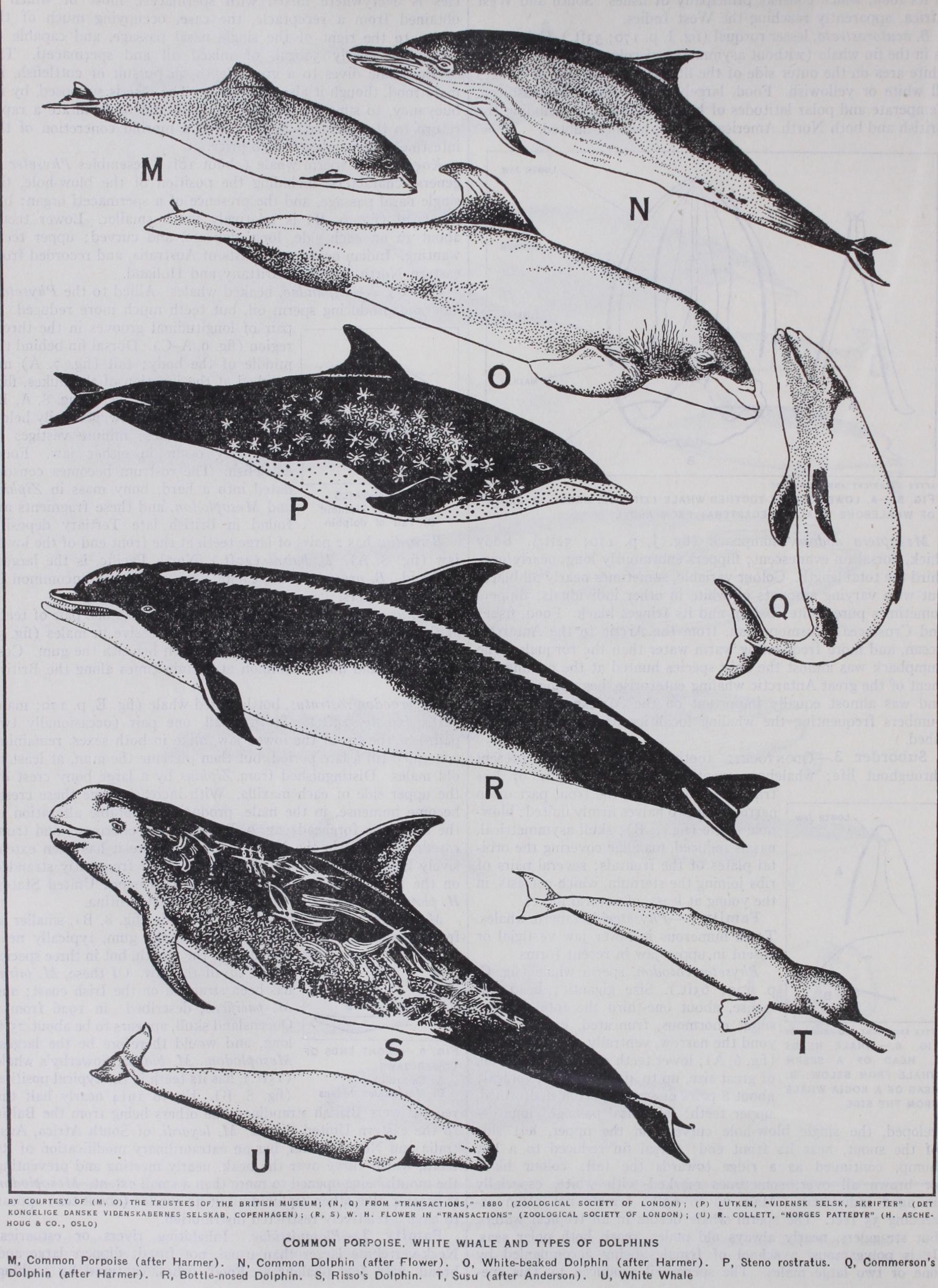

Platanista gangetica, Susu (fig. T, p. 172; 8ft.). Blind; dorsal fin reduced ; remarkable, large bony crests at the base of the ros trum. Teeth about 30 on either side of each jaw. Ganges, Indus and Brahmaputra, nearly to their head waters.

Lipotes vexillifer (8ft.), with a similar dorsal fin, is whitish all over, its upper jaw curved upwards. Teeth about 32. Tung Ting lake, about 600m. from the mouth of the Yangtse Kiang river. Inia geo f}rensis (8ft.), also with a reduced dorsal fin. The beak is covered with numerous short hairs, a primitive feature. Teeth, 26-32. Amazon river, from near its head waters.

Stenodelphis (or Pontoporia) blainvillei (5ft.). Dorsal fin well developed; jaws long and delicate; teeth 50-6o. La Plata estuary.

Family

4.—Delphinapteridae. Dorsal fin wanting; neck verte brae free ; flippers broad ; dermis of skin more developed than usual. Food, mainly cuttlefish, but also fishes.Delphinapterus leucas, white whale or Beluga (fig. U, p. 172; I 8f t.) . Adult pure white all over, young dark brown-grey; teeth 8-1o, diameter 20 millimetres. Arctic and circumpolar, reaching the St. Lawrence and (rarely) the British coast. Formerly hunted on a large scale.

Monodon monoceros, narwhal (fig. D, p. 17o; 15-2oft.). Adult greyish-white, with leopard-like spots, sometimes whitish when old ; young unspotted ; teeth unlike those of any other animal, reduced (except for vestiges in the foetus) to a single upper pair. In females these remain concealed in the bone, but the left one exceptionally develops as in the male. The right tooth of the male remains similarly concealed, but the left tooth, the horn of the traditional Unicorn, grows spirally to an enormous length, up to 9ft., 42in., projecting forwards from the upper lip. In rare cases the asymmetry may be reversed, the right tooth becoming the tusk ; or the animal has two tusks, about equally developed. One or two "bidental" specimens have been recorded as female, but further evidence on the sex is required. Arctic, rarely reaching Britain. Large numbers of narwhals are killed by the Esquimaux in certain parts of Greenland, where the males protrude their tusks through holes in the ice when they rise to breathe.

Family

5.—Delphinidae, dolphins (fig. 1). Dorsal fin present, except as noted be low. Neck vertebrae mostly fused with one another; tail (fig. 7, B) with a notch at the junction of the flukes; flippers gen erally pointed and sickle-shaped ; teeth (except Grampus) in both jaws, usually numerous. The numbers recorded below (on either side of each jaw) do not include the reduced teeth commonly found at the front end on both jaws, below the gum.Delphinus delphis, common dolphin (fig. N, p. 172 ; 8ft.). Beak about 5in. long in middle line, separated from rest of head by a distinct groove (fig. Io, A), a char acter obvious in representations of this animal on Greek coins and elsewhere. Mainly black above and white below, the sides with longitudinal streaks of white, brown, yellow or grey. Palate of skull with two deep, longitudinal grooves. Teeth 40 50, diameter 3-3.5 millimetres. The "dol phins," which pursue flying fish and change colour when dying, are fishes (Coryphaena), not to be confused with the cetacean.

Cosmopolitan, common in the Atlantic and Mediterranean, fre quently stranded on the British coasts, but rarely on the east side of England. Food, fishes and cuttlefish. The stomach of a Medi terranean specimen was found by Dr. J. Schmidt to contain 15,191 otoliths (ear-bones), indicating the recent consumption of more than 7,500 small fishes.

Prodelphinus, with many species, often spotted or with longi tudinal dark lines on the sides, is oceanic. Beak and teeth as in Delphinus, but palate of skull not grooved.

Lissodelphis peronii. Black and white, sharply delimited, the white including the flippers and continued past the mouth to the upper side of the "forehead." Dorsal fin wanting. Teeth as in Delphinus. Southern seas, with one record from New Guinea.

Lagenorhynchus. Beak short, usually distinct (fig. 10. B) ; sides generally with oblique light areas ; upper and lower keels of root of tail strongly marked; vertebrae numerous, about The two following British species, also found in eastern United States, reach 9ft., the beak tin. long in the middle line :—L. al birostris, white-beaked dolphin (fig. 0, p. 17 2) ; upper lip white; teeth 22-25, diameter 7 millimetres.—L. acutus, white-sided dol phin; upper lip black; very distinct light areas on the sides; teeth 30-34, diameter 4 millimetres. Other species in Indian, Pacific and Southern oceans.

Cephalorhynchus (fig. Q, p. 172). Small dolphins, about the size of the common porpoise, from southern seas, usually con spicuously coloured and without sharply marked beak. Teeth 25-31, small.

Steno rostratus (fig. P, p. 172; 8-ft.). Mainly dark, spotted with white; beak long, distinct; teeth 20-27, large, with slightly rugose crowns. Atlantic and Indian oceans.

Sotalia. Resembling Steno, but teeth more numerous (up to 35), with smooth crowns. Species of Sotalia occur in fresh water in China (colour, milky white) and the Amazon. S. teuszii, from the Cameroons, has been found to contain leaves, mangrove fruits, and grass in its stomach. Other species, from the tropical parts of the Indian and Atlantic oceans.

Tursiops. Beak rather longer than in Lagenorhynchus, teeth larger. T. truncatus, bottle-nosed dolphin (fig. R, p. 172 ; 10 I Ift.), is common in British seas and off the eastern United States. Dark above and white below; teeth 20-23, large, diameter 8.5-10 millimetres. Other species from the Mediterranean, Red sea, North Pacific, Australia and New Zealand. The natives of Moreton bay, Queensland, are said to co-operate with schools of dolphins (prob ably Tursiops) in beach fishing, the dolphins driving the fishes ashore and being rewarded for their assist ance by fishes offered on the points of spears.

Grampus griseus, Risso's dolphin (fig. S, p. 172; I 'ft.). Nearly uniformly grey ish ; beak wanting, forehead prominent; flippers long; teeth completely absent in upper jaw (except for rare vestiges) ; lower teeth, 2-7, confined to the front end of the jaw, large, diameter 14 millimetres. Ap parently cosmopolitan, reaching Britain and the eastern United States. "Pelorus Jack," an individual which was well known in New Zealand, a few years ago, from its habit of accompanying steamers in Pelorus Sound, is believed to have belonged to this species.

Globicephala. Forehead greatly swollen and prominent (fig. 1o, C) ; flippers spe cially long. G. melaena, pilot whale, black fish or caa'ing whale (28f t.) is black all over. Teeth 7–I I, large, diameter io–i mm., at the front end of the jaws. Large schools have frequently been driven ashore, 1,540 individuals having been killed in two hours, in 1845, at the Shetland islands. 117,456 individuals are known to have been captured at the Faeroe islands between 1584 and 1883. Both sides of the Atlantic and in Pacific, Indian ocean and southern seas.

Pseudorca crassidens, false killer (I 9f t.) . Teeth 8-1o, almost as large as those of the killer ; black all over, flippers narrow. Originally described by Owen from a subfossil skeleton from the Lincolnshire fens. Two skeletons have recently been found in the Cambridgeshire fens. A school of more than a hundred specimens was stranded in the Bay of Kiel in 1861, and a school of about 15o on the east coast of Scotland in 1927. It is said to occur in large parties off New Zealand and Tasmania, and it has been recorded from India, Queensland, both sides of North America and Argentina.

Orcella brevirostris (7ft.). Head as in Grampus, dorsal fin low; rostrum of skull very short ; teeth 12-14, small. Ascends the Irra waddy river, Burma, to goo miles from the sea, and occurs in the Bay of Bengal, and off Singapore and Borneo.

Phocaena and the two following have teeth with an expanded, spade-shaped crown, differing from the conical teeth of other dol phins. P. phocaena, common porpoise (fig. M, p. 172; 51f t. ), is black above and white below, with some variation. Head short, without beak (fig. 1o, D) dorsal fin triangular, commonly with small, horny tubercles on its front edge. Male reproductive open ing unusually far forward, below the dorsal fin ; teeth 2 2-26. The porpoise was formerly much in request as an article of diet, and there were important fisheries off Normandy and at the entrance to the Baltic. It frequents coasts and often ascends rivers. It is specially characteristic of the Atlantic coasts, on both sides, and it reaches the Azores. The porpoise of the Black sea and eastern Mediterranean has been considered distinct. Other species from South America.

Neomeris. Resembles Phocaena in having skin-tubercles, but has no dorsal fin. Teeth 16-21. India and Japan (marine) ; Tung Ting lake and other parts of the Yangtse Kiang, hundreds of miles from the sea.

Phocaenoides, with two species from the North Pacific, also has skin-tubercles. Teeth 19-22, much smaller than in Phocaena; vertebrae specially numerous, 95-98, as compared with in Phocaena phocaena.

Orcinus orca, killer or grampus (male 3I ft.; female, 16ft). Beak wanting; dorsal fin large; flippers very broad, not pointed; teeth exceptionally large and strong, diameter 2in. ; colour pattern bold, the black and light parts sharply delimited (fig. I). The white (or yellow) extends over the lower jaw and the lower side of the tail-flukes; and, just behind the dorsal fin, is pro duced backwards as a lobe defined below by a tongue of black passing forwards from the tail; a conspicuous white area, above and behind the eye; and a less distinct triangular mark behind and below the dorsal fin. The male is nearly twice the length of the female and all its fins increase greatly in size with age, to an extent disproportionate to the body-length. The dorsal fin, at first recurved as in the female, becomes an erect triangle 51f t. high. The flippers reach a size of 6x4ft., their enlargement being due mainly to the inordinate growth of the cartilage of the phalanges. Food, fishes and marine mammals and birds. Eschricht found the remains of 13 porpoises and 14 seals in the stomach of a killer, and gave reasons for believing that seals are flayed after being swallowed, the skins being then disgorged. The story that killers combine to attack a large whale, forcing its mouth open and eating the tongue, has recently been confirmed by R. C. Andrews. Although a killer should be regarded as a dangerous animal there seems to be little evidence that it willingly attacks man. The motive for a combined assault, by a party of killers, on an ice-floe, as recorded in Scott's Last Voyage, may have been the capture of the dogs (mistaken for seals), and not of the man. 0. orca, if all killers belong to one species, is cosmopolitan, ex tending from Pole to Pole, though it is apparently not often found in the tropics. It is not uncommon in British and American waters Feresa and Sagmatias are little known genera.