Ceylon

CEYLON, a large island and British Crown Colony in the Indian Ocean, separated on the north-west from India by the Gulf of Manaar and Palk Strait. It lies between 55' and 9° 51' N. and between 79° 41' and 81° 54' E; its extreme length from north to south is 2721 m. ; its greatest breadth is 1374 m. ; area 25,481 sq.m., five-sixths that of Ireland.

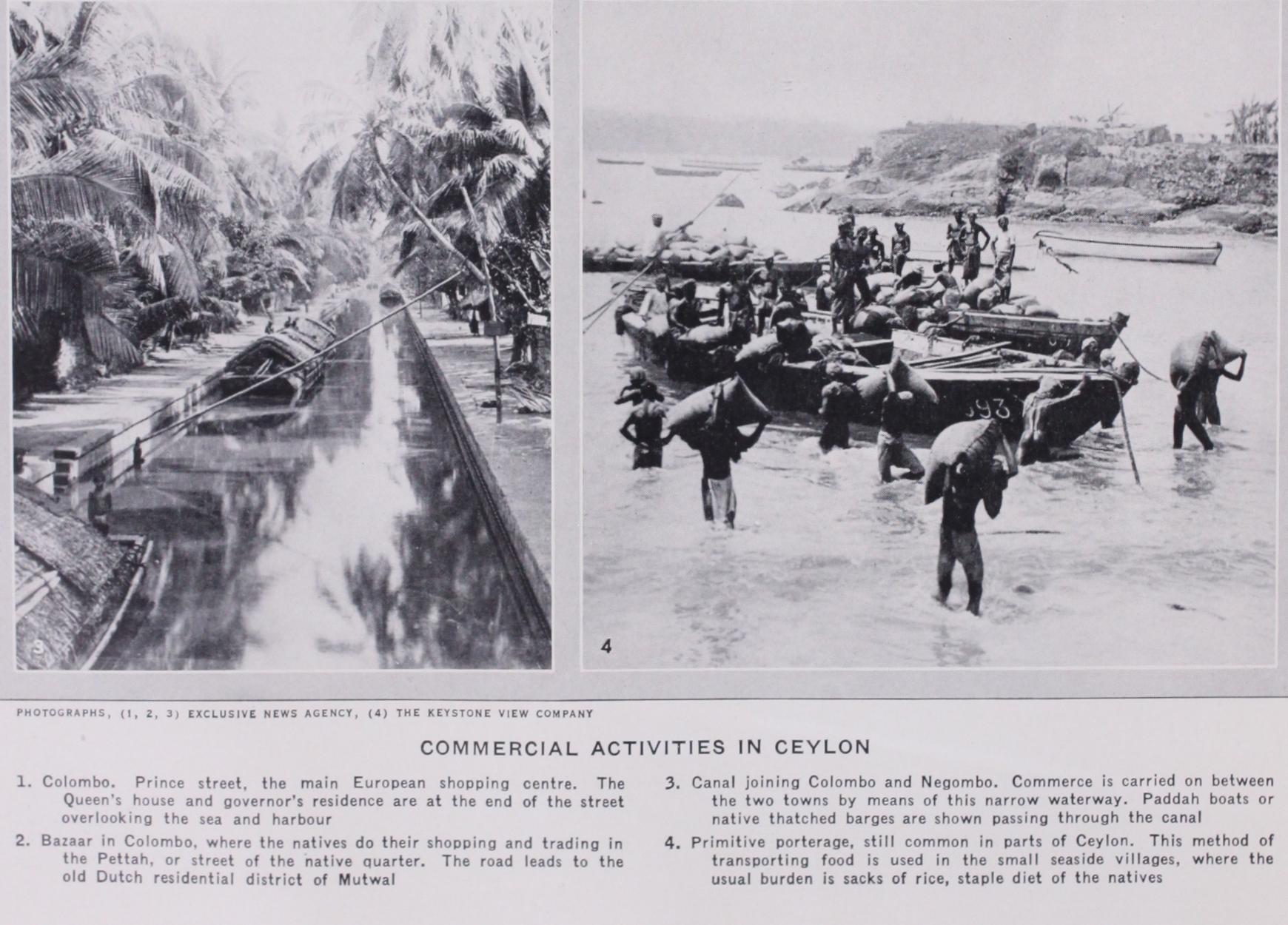

The coast is beset on the north-west by numerous sand-banks, shoals and rocks, and the island of Manaar, which forms an integral part of Ceylon, is almost joined to the island of Rame swaram by the chain of sand-banks named Adam's Bridge (q.v.). Of the channels through these shoals, Manaar Passage and Paum ben Passage, the latter is the better though negotiable only by vessels of light draught. The west coast from Puttalam south ward, and the whole south coast are fringed by coconut palms which grow almost to the water's edge. Along these shores there are numerous inlets and lagoons, often linked by canals, mostly constructed during the Dutch occupation. The east coast is more rugged and lacks the luxuriant vegetation of the west and south of the island. Deep water is usually available close to the shore, though there are a few dangerous rocks, well known to navigators.

Mountains.

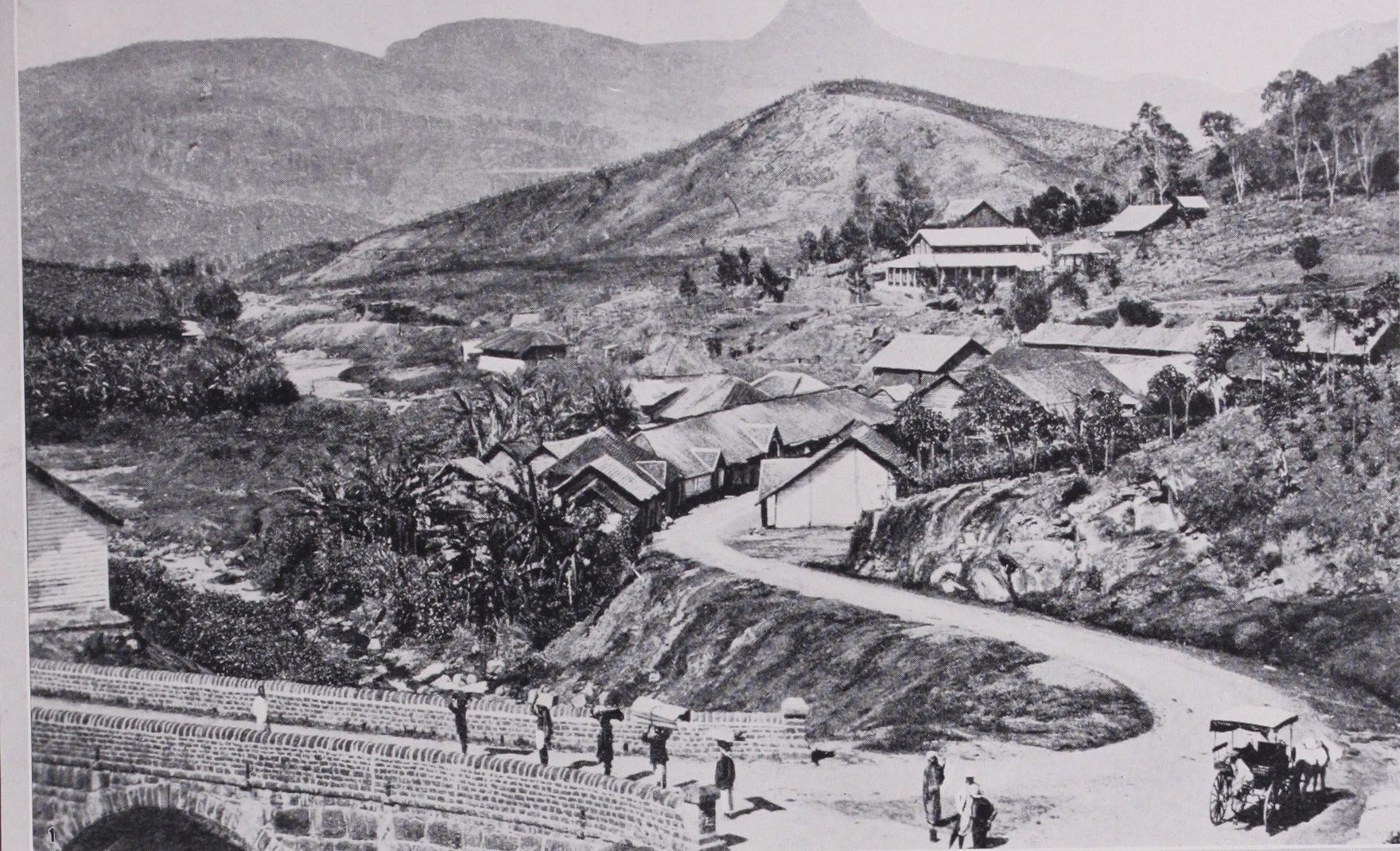

A massif occupies the centre of the southern portion of the island covering 4,212 sq.m., the foothills rising from the flat plains 45 to 7o m. from the coast. The highest peak, Pedrutalagala (8,296 ft.), dominates the hill-station of Nuwara Eliya (6,000 ft.) ; Adam's Peak (q.v.) is visible to vessels ap proaching the harbours on the west coast and from Colombo. This massif intercepts the rains of both monsoons, whereas the arid "dry zone," which extends northward uninterruptedly from the neighbourhood of Dambulla, was only rendered habitable by a large population in ancient times by one of the most elaborate and skilful irrigation systems ever devised. This fell into dis use and, though much restoration work has been undertaken dur ing the period of the British occupation of Ceylon, malaria has hitherto defeated all attempts to colonize this area anew. The rainfall of the south-west is far heavier than that of the north east monsoon, and as a consequence the western and southern districts near the mountains are far more fertile than those on the east side. Practically the whole west side of these mountains, up to an altitude of 5,000 ft., is to-day under tea; but on the eastern flanks the natural forest of the west and south slopes is re placed by rolling downs of rank grass strewn with great boulders. These are termed patnas, and till recently were regarded as un suitable for tea; large areas have now been converted into tea estates. At the time of the conquest of Kandy (I 815) the moun tains were covered with virgin forest ; the Kandyan villagers had their homesteads in the deep valleys, and cultivated rice on any available flat ground and also on terraces cut out of the hillsides to a height of only a few hundred feet above the valley-levels.The plateau of Nuwara Eliya, the famous health-resort, is 6,000 to 6,200 ft. above sea-level. It enjoys an almost perfect climate from September to April, though even during those months rainy days are common. From May to August rain falls almost daily. The Horton Plains (7,00o ft.), though they have not so far been extensively developed and are mainly used by anglers, possess an even more invigorating climate than that of Nuwara Eliya. The other principal hill stations in Ceylon are Badulla, Bandarawela, Diyatalawa, Hatton and Kandy (q.v.).

Rivers.

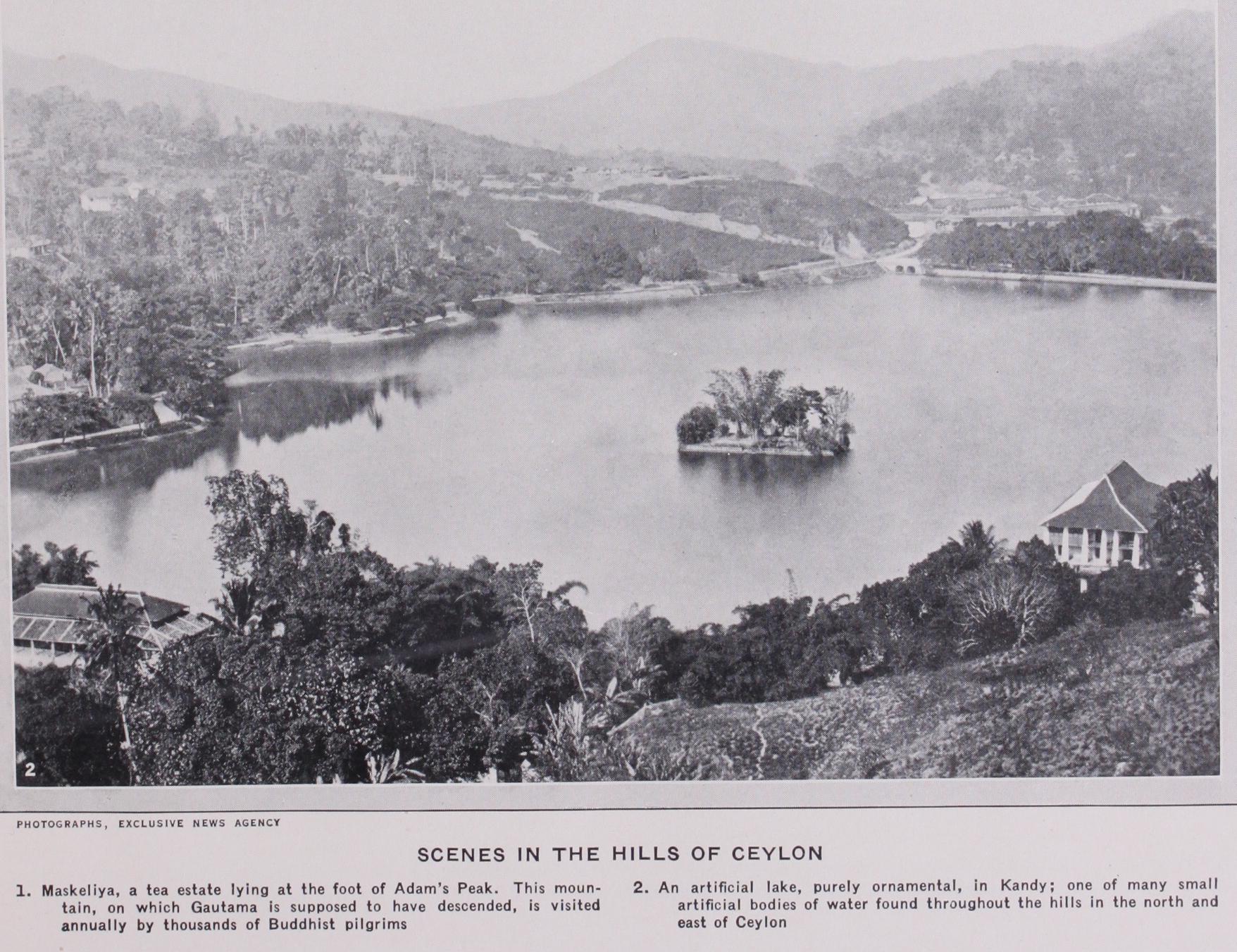

The largest river is the Mahaweli Ganga which, drain ing the west slopes of the mountains, falls into the sea at Trin comalee, on the east coast, after flowing for a distance of 206 miles. Like all rivers of Ceylon, it is navigable only in the lower reaches, where tobacco and other crops are grown by Sinhalese and Tamil cultivators. Its rapid-beset course is a scenic feature near Kandy and in the botanic gardens of Peradeniya, the finest in the tropics. The Kala Ganga falls into the sea at Kalutara, and the Kelani Ganga debouches near Colombo. Against the latter's floods considerable engineering-works have of late been con structed. In the northern part of the island many water-courses are dry most of the year, but all rise in sudden spate after heavy rain. The lakes which abound in north and east Ceylon are all in some measure, and many entirely, artificial. Of these the largest is Giant's Tank (6,000 ac.) , in the Northern Province ; Minneri and Kalawewa, in the North Central Province, are about 4,000 acres each.

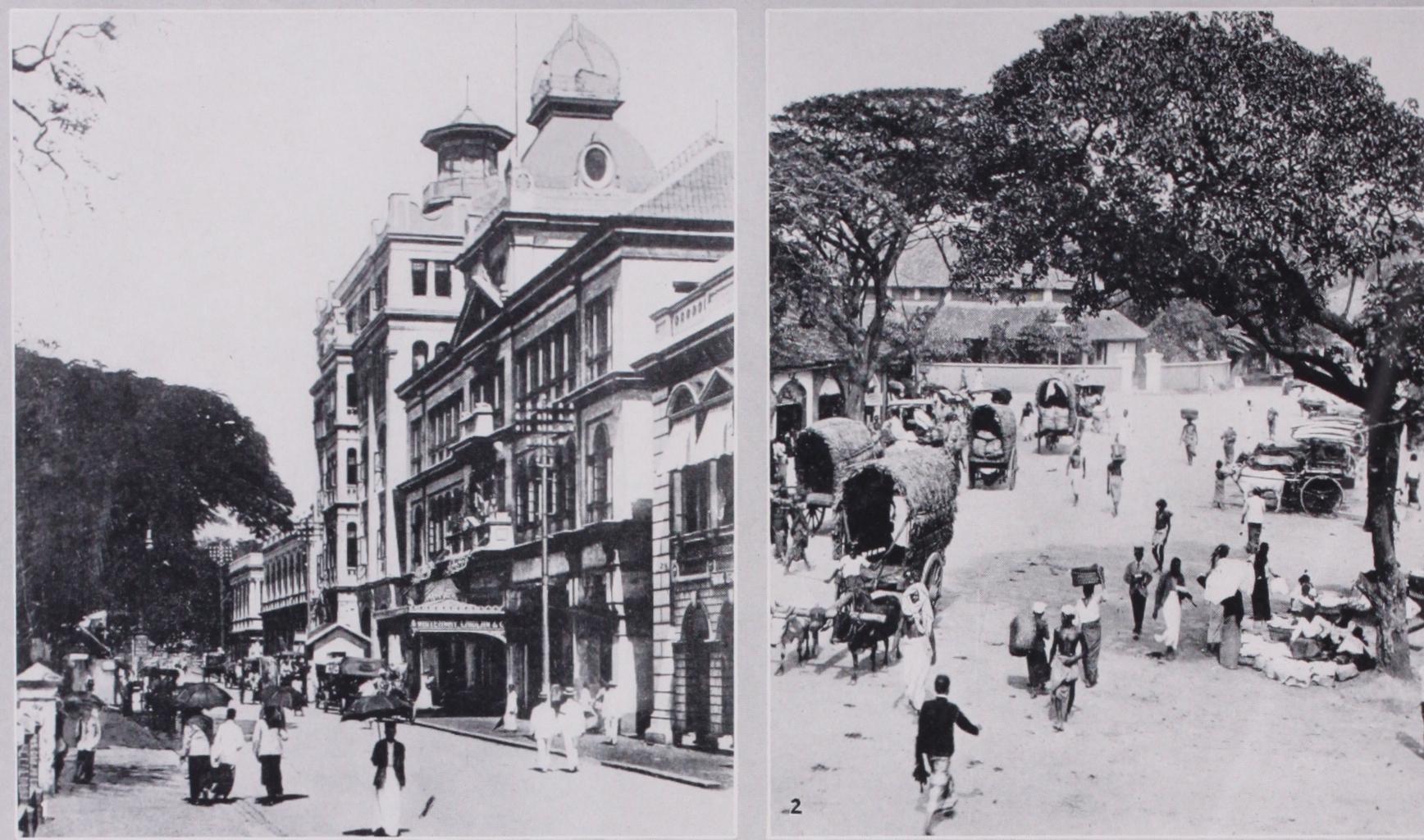

Trincomalee, on the east coast, is one of the finest natural har bours in the world. Galle was the principal harbour of Ceylon on the west. coast until Colombo, by elaborate harbour-works which were begun towards 188o, was made the chief port of the island.

(H.

CO Geology.—The greater part of the island is occupied by ancient crystalline rocks in which pyroxene-gneisses are intrusive in the older ortho-gneisses and belong to the Charnockite series of South ern India. They are character ized by enstatite and a varying proportion of monoclinic pyrox ene, hornblende and biotite. Typi cal Charnockite is a quartz-plagio clase-enstatite granite. By in crease of ferro-magnesian min erals the rocks graduate into noritic varieties, rich in garnet. Except in the centre of some of the larger intrusive masses the rocks show marked mineral banding and granulitic structure. Veins and sills of pegmatite are common and frequently contain compounds of thorium and uran ium as accessory minerals. A narrow band of Tertiary sedi ments borders the north-west coast and forms the Jaffna penin sula in the north. A small outlier of the same rocks is found on the south coast. Recent deposits of sand, mainly the result of marine agencies, fringe the rest of the coast as sand-bars enclosing lagoons and coastal flats, while the river valleys are filled with recent alluvium. In the low country the crystalline rocks are generally overlain by a thick mantle of laterite, resulting from their decomposition. The economic minerals of importance are-0) graphite (plumbago) (2) gem stones. Graphite is found in veins which may be regarded as a special type of pegmatite. The principal mines lie in groups in the south-west quarter of the island. The gem-stones, the most important of which are sapphire and other varieties of corundum, are won almost entirely from river-gravels. The gem-fields lie on the south-west flank of the main mountain-mass.

Climate.

The south-west and north-east monsoons are the distinctive feature. The former is very regular in its approach, appearing along the south-west coast between May so and 20; the latter reaches the north-east coast between the end of October and the middle of November. The south-west monsoon brings rain to the western and southern coasts but does not reach the opposite side of the island. The mountains of the south-west sharply mark the wet and dry regions. The influence of the north-east monsoon is more general. The mountains in the north-east are lower and farther from the sea than those on the south-west, and rain is carried farther inland, giving general precipitation. The length of the day, owing to the proximity of the island to the equator, does not vary more than an hour at any season. Colombo is situated in 45" E., and the day is further advanced there than at Greenwich by 5 h. 19 m. 23 s.

Flora.

On sandy shores a screw-pine (Pandanus tectorius), Clerodendron inerme, Scaevola frutescens, Cerbera Mangjias, Tliespesia populnea, Dolichandrone spathacea, Ipomaea Pes caprae, Spini f ex littoreus, Lippia nodiflora and Crinum asiaticum are common. On muddy shores, a mangrove formation with Bru guiera conjugata, B. sexangulata, R/iizophora conjugata, R. muc ronata, Sonneratia acida, Avicennia marina, Ceriops Tagal, Aegiceras corniculatum, Lumnitzera racemos s and Acanthus ilici folius is found.On the south and west coasts the Coconut palm has been ex tensively planted, while on the north it is replaced by the Palmyra palm (Borassus flabellifer), but neither of these is a native of Ceylon.

In the dry north and east occur Salvadora persica (the Mustard tree of Scripture), Azima tetracantha, Acacia eburnea, Carissa spinarum, Ziziphus Jujuba and Randia dumetorum, in the low growing scrub-jungle near the coast. Further inland are forests with valuable timber trees, Satin-wood (Chloroxylon Swietenia), Ebony (Diospyros Ebenuni), Tricomalee wood (Berria cordi f olia), Milla (Vitex pinnata), Ranai (Alseodaphne semecarpifolia), etc. The beautiful Indian Laburnum (Cassia Fistula), C. Roxburghii, C. auriculata (which yields the Ranavara Tea), Crataeva Rox burghii, Derris scandens (like a white Wistaria) and Ixora coc cinea are conspicuous. The Riti or Upas tree (Antiaris toxicaria), the bark of which was formerly used by the Veddas for making clothing, is found in this part of the island. Herbaceous plants belong mainly to the families Leguminosae, Acanthaceae, Scrophu lariaceae Asclepidaceae and Cucurbitaceae. Ferns and orchids are comparatively rare.

The wet south-west and its affinities has mainly Malayan affini ties, but with local species. The trees grow much higher than in the dry zone. Forty species of Dipterocarpaceae are confined to this region, and species of Palaquium (Sapotaceae), Calophyllum (Guttiferae) and Diospyros are also numerous. These forests produce the valuable woods Nedun (Pericopsis) Mooniana and Calamander (Diospyros quaesita). The few herbaceous plants in the forests are mainly Rubiaceae, Acanthaceae and ferns. The Wesak flower (Dendrobium Macarthiae) among orchids and the ribbon fern (Ophioglossum pendulum) are the most interesting of the epiphytes, which though more numerous than in the dry zone are less common than in the montane zone. The curious pitcher-plant (Nepenthes distillatoria) and the beautiful Burman nia disticha are common in open marshy places. Acrostichum aureurn is a conspicuous fern in similar places, especially near the sea. Helminthostachys zeylanica a curious fern related to the Moonwort is found on wet sandy soil.

At higher altitudes the trees are smaller and usually flat-topped with numerous species of Syzygium, Elaeocarpus and Lauraceae; Calophyllum Walkeri, Michelia nilagerica, Meliosma Arnottiana and Gordonia zeylanica are ornamental. The undergrowth con sists chiefly of various species of Strobilanthes. Climbing plants are less common than in the low country but include the lovely rose-red Kendrickia Walkeri. Many shrubs and herbs belong to genera represented in England, e.g., bramble, violet, butter-cup, sundew and ladies' mantle.

Tree-ferns and filmy-ferns are especially noticeable ; mosses, liver-worts (except Lejeuneae) and many families of lichens are more abundant than at lower elevations; orchids are also com mon, the daffodil orchid (Ipsea speciosa) and the hyacinth orchid (Satyrium nepalenae) are found on the ground on the patanas, while the lily-of-the-valley orchid (Eria bicolor), Dendrobium aureum and Coelogyne odoratissima are common epiphytes. Large open tracts of grass, called patanas and talavas by the Sinhalese, originally produced by periodic burning of the forest, are gradu ally extending. In the dry zone they have coarse grasses like Aristida setacea, Heteropogon contortus, and, about Batticaloa, of Iluk (Imperata cylindrica). In the wet zone up to about 5,00o ft. they consist mainly of mana grass (Cymbopogon confertiflorus) a fern (Gleichenia linearis) often with a few stunted trees such as the Patana oak (Careya coccinea). Above this elevation the grasses are mainly Arundinella villosa, Chrysopogon zeylanicus, and Ischaemum ciliaris var. longipilurn; herbaceous plants are more numerous, the purple osbeckias being especially noticeable. Rhododendron arboreum, with large red flowers, is the only woody plant common on the patanas at this elevation. Large numbers of foreign species include Lantana aculeata, found everywhere along roadsides and on the patanas, the water-hyacinth (Eichhornia crassipes) blocking the irrigation channels of the rice fields in the low moist zone, Mikania scandens and Ageratum conyzoides. Timber trees like Jak (Artocarpus integrifolia) and Sapu (Michelia champaca) are also of foreign origin.

Fauna.—The elephant of Ceylon is considered a local sub species of the Indian form, with tusks rarely developed. Elephants are still numerous in wilder parts, though much scarcer than when the greater part of the island was under forests. They are found at all elevations up to 7,500 feet. At intervals, a herd is driven by an army of beaters into a strong stockade or kraal in the jungle. Each is then noosed with the aid of tame elephants, and tied to trees by the legs. After a short period of discipline they become reconciled, but many captives die within a year. Tame elephants are used in building operations, transporting machinery etc., but chiefly in ceremonial processions.

The small oxen are hardy and capable of drawing heavy loads. Buffaloes (Bubalus bubalis) are common, wild and tame. Tame ones plough rice fields and tread out grain but otherwise lead a semi-wild life.

Ceylon possesses four deer—the Sambhur or "Ceylon Elk" (Rosa unicolor), the Spotted Deer (Axis axis), the Muntjac or "Barking Deer" (Muntiacus nialabaricus) and the Hog Deer (Hyelaphus porcinus), the last probably introduced by the Dutch. A little Chevrotain, the "Mouse Deer" (Moschiola meminna), is also common. There are no antelopes in Ceylon.

There are five species of monkeys, one the small Rilawa (Macacus sinicus) which is found everywhere, and four known by the name of "Wanduru" (Pithecus ursinus, P. vetulus and sub species, P. philbricki and P. Priam). The only other member of the Primates is the little Slender Loris (Loris tardigradus) which creeps about the trees at night, and feeds on small birds, insects and fruit. Twenty-four Chiroptera have been identified : the large fruit eating bat or "Flying-fox" (Pteropus giganteus) roosts in large colonies in tall trees, often choosing those on small islands. At night it does much damage in mango groves, etc..

The tiger is not found in Ceylon, but the leopard (Fells pardus) and several smaller wild cats are common. The only carnivore ordinarily dangerous to man is the Sloth Bear (Melursus ursinus) found in the wilder parts. Jackals (Canis lanka), Otters (Lutra lutra), Palm Cats (Paradoxurus) and several species of Mon gooses are common. Rats and Squirrels of many species are found, also a Porcupine (Acanthion leucurus) and a Hare (Lepus singteala). The Dugong (Halicore dugong) occurs in the shallow seas to the north and north-west of the Island and is captured for food to some extent. The only representative of the Edentata is the Pangolin (Mavis crassicaudata).

Some 372 species of birds are recorded, about 120 being winter migrants from Asia, and 5o others accidental or occasional visitors. About 6o species or subspecies of resident birds are more or less distinct from the nearest Indian forms. Among these endemic species, the more noteworthy are the Ceylon jungle-fowl (Gallus lafayettii) the blue magpie (Cissa ornata), the yellow-eared bulbul (Kelaartia penicillata), the grey-headed babbler (Turdoides cine reifrons), the red-faced malkoha (Phaenicophaes pyrrhocephalus), the green-billed coucal (Centropus chlororhynchus) and Legge's flowerpecker (Acmonorhynchus vincens). The avifauna of the high rainy south, includes most endemic species and shows a close affinity to that of the Travancore hills, while the birds of the dry, flat north are more like those of the Carnatic. Bulbuls, babblers, barbets, kingfishers and crows of many kinds are ubiquitous. Thrushes, flycatchers, chats, drongos, mynahs and sunbirds are all well represented, while cuckoos, parroquets and woodpeckers are many and varied. Hawk-eagles, hawks and owls are numerous in species. Pigeons of many kinds, and game birds are common, the latter including peafowl, junglefowl and two species of francolins. The large artificial lakes in the dryer parts of the island are fre quented by large numbers of herons, storks and other waders, and by resident and migratory species of teal, etc. Terns form the principal element in the sea fowl, the few species of gulls being winter visitors only, as are also nearly all the snipes, plovers and shorebirds.

Probably the only kinds of poisonous snakes to be feared are the Cobra (Naia tripudians) and the "Tic Polonga" or Russell's Viper (Vipera russelli). Other venomous species are either very slightly so or very rare. The Python or Rock Snake (Python molurus) is found in the jungles and Rat Snakes (Zaocys mu cosus), and Green Whip Snakes (Dryophis mycterizans) are common.

Two species of crocodiles occur,

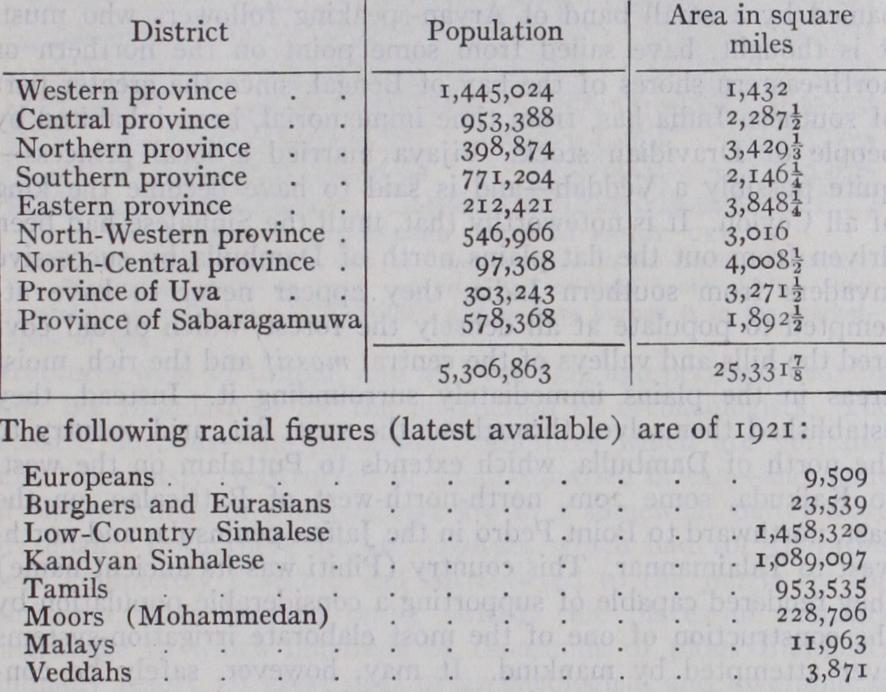

Crocodilus palustris, in the large artificial lakes in the interior, and the larger C. porosus, in the larger rivers and estuaries. Both are becoming reduced in number as they are much shot for their hides. The large terrestrial Monitor or "Tallagoya" (Varanus bengalensis) is suffering a simi lar fate, and its larger relative, the aquatic "Kabaragoya" (Varanus salvator) has had to be protected by law. The com monest lizards are several species of the genus Calotes, known as "Bloodsuckers." There are also many Skinks and Geckoes, but the flying lizards (Draco) are unrepresented.Some thirty-seven species of frogs and toads are recorded. The only other Amphibian is the legless Caecilian, Ichthyophis glutinosus. (J. PN.) Population.—The total population of Ceylon in 1931, exclu sive of military and shipping elements, was 5,306,863, as against about 1,700,000 in 1857. The increase during the decade 1921 to 1931 was 17.97%. The population of Colombo was The population and area of the nine provinces was as follows: Altogether there are representatives of some seventy races in Ceylon. The Veddahs, who live in rock-shelters and run wild in the woods, are the aborigines.

Education.

In 1926 there were in the island 272 English schools attended by 50,114 scholars, of whom 11,703 were girls; 112 Anglo-Vernacular schools, with 23,809 scholars, of whom 4,995 were girls; 4,009 Vernacular schools, with 409,827 scholars, of whom 150,104 were girls. Government schools of these classes numbered respectively 17, 6o and 4,009; grant-in-aid schools 226, 36 and 1,823; unaided schools 29, 16 and 1,085. Grants in-aid defray practically all current expenses, including salaries of teaching staffs of non-Government schools. Such technical and agricultural schools as exist are sparsely attended. A large class of semi-educated youths, despising manual labour but unfit for clerical work adds annually to the number of idle malcontents. In 1921 the number of literates in the island was 1,537,594 of whom 381,475 were females, and the number of English literates 144,509 of whom 3 7, 213 were females.

Language.

Sinhalese is spoken by about two-thirds of the population. Tamil is used alike by more than half a million Ceylonese Tamils, by Ceylon and Indian Moormen, who number about 290,00o, and by the Tamil immigrant labourers, a floating population of about 700,000 souls. A Batavian dialect of Malay is spoken by descendants of Malayan troops imported by the Dutch. An archaic corrupt form of Portuguese is in use among descendants of the earliest European invaders. The aboriginal Veddahs speak a language of their own, the affinities of which are obscure. No worthy dictionary of Sinhalese exists, but one has recently been begun by the Ceylon branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, with funds voted by the Legislative Council. Sinhalese is an Aryan language closely related to Pali (q.v.). Though minor dialectal differences occur, the spoken language is practically the same throughout Ceylon. Sinhalese possesses little literature of value, Pali having been used for the composition of the famous chronicle of the Mahawansa and for most of the poems, etc., of any merit written in Ceylon. Many of these, however, have been translated into Sinhalese.Religion.—According to the census of 1921, the population of Ceylon was composed of Buddhists 2,769,805, Hindus 982,073, Mohammedans 302,532, Christians of whom were Roman Catholics, 44,730 Anglicans, 17,345 Wesleyans, Presbyterians, 3,511 Baptists, 1,165 Salvationists, 933 Congrega tionalists and 3,681 of other denominations. Buddhism, the pre dominant religion was introduced by the 3rd century B.C. The large Buddhist priesthood from time to time has produced many learned men ; but the natural religion of the peasantry still finds expression in many observances, probably of pre-Buddhist origin. Ceylon Buddhism moreover recognizes many Hindu gods and goddesses. A great revival of Buddhism in the last 20 years is political rather than religious and accretions have come in from other creeds. Christian practice has prompted Young Men's and Young Women's Buddhist Associations and Islam the doffing of shoes on entering Buddhist Temples. Simultaneously the broad toleration of other faiths, which from the earliest times has been so marked and so noble a feature of pure Buddhism, has shown a tendency to be replaced by vulgar abuse of the tenets of other creeds of a kind with which the more ignorant types of Christian missionaries "to the heathen" have unhappily made the world familiar. The simple faith of the people leads enormous num bers of pilgrims to the principal shrines and temples at each full moon, and to the universal observance of such Buddhist feasts as Wesak, the birthday of Gautama. Adherence to Buddhism, however, has done nothing to wean the Sinhalese as a whole from the consumption of alcohol, though there is now among educated Sinhalese and Tamils alike a vigorous temperance movement. The large number of crimes of violence among the Sinhalese shows that Buddhist teaching has not succeeded in imbuing them with a sense of the sanctity of human life; while, though they for the most part hesitate to take animal life, their treatment of domes tic animals is cruel and callous in the extreme.

Agriculture.

The natural soils are composed of quartzose gravel, felspathic clay and sand, often of a pure white blended with or overlaid by brown and red loams, due to decay of vege table matter, or disintegration of gneiss and hornblende forma tions. The whole consists of a sandy and calcareous soil admix ture, which in ancient times yielded large crops of rice and other food-stuffs, owing to an elaborate system of irrigation, but which to-day is for the most part uncultivated, this part of Ceylon sup porting a degenerate and dwindling population. Only in the Jaffna Peninsula, and to some extent in Manaar, where indefatigable Tamil industry irrigates the soil by water drawn from wells, and where the cultivation is intensive, are crops of grain, tobacco and vegetables annually wrung from the ungrateful earth. A little further to the south lie extensive plains of alluvial soil, washed down from the mountains. The soil of the maritime provinces is sandy, but large tracts of quartzose sand along the shore are very suitable for coconut and cinnamon cultivation. The former is rapidly extending, the latter has diminished. From this light sandy belt as far as the foothills, the land is mainly composed of flats which yield large rice-crops, and of low hilly undulations, large areas of which up to a height of some 2,000 ft. are now under rubber, introduced towards the end of the nineteenth century. The soil of the mountain area, though frequently containing great quantities of quartzose sand and ferruginous clay, is often of a fine loamy character, suitable for coffee and for tea-cultiva tion. The south and west sides of these mountains have been cleared of forest up to a height of 5,000 ft., and in a few instances above that level; and until quite recently very little was done to check or control the erosion of the soil annually caused by the abundant rainfall. In the low country large extents of land for merly under tea are now converted into rubber estates, tea of the best quality being obtainable only at higher altitudes. Over 442,000 acres in the island are now under tea, about 475,000 acres under rubber, 900,000 under coconuts and about 834,000 acres of "wet" land under rice, about 35,000 acres under cocoa, 25,000 under cinnamon, 24,00o under tobacco, 68,000 under areca-nuts and about 6,30o under cardamoms.

Products.

In 1926 the quantities of these articles exported from Ceylon were : Tea, 217,083,648 lb. valued at Rubber, 131,840,505 lb. valued at R170,078,219; Products of the coconut-palm valued at R79,146,085 of which copra amounted to 2,419,398 cwt. valued at R39,848,479 and coconut-oil to gallons valued at R15,489,320; Cocoa 64,751 cwt. valued at R1,953,684; Cinnamon chips 11,874 cwt. and Cinna mon quills 31,238 cwt. valued at R4,209,771; Tobacco, manu factured 13,762 lb., unmanufactured 1,972,754 lb. valued at R456,717 lb.; Cardamoms, 2,845 cwt. valued at R841,961; and Areca-nuts, 165,475 cwt. valued at R4,247,825. There were also exported 1,431,351 lb. of citronella oil. As regards rice, so far is Ceylon from being self-supporting that of this, the staple article of food-consumption, 650,964 cwt. valued at R3,305,624 were imported in 1926.The prosperity of Ceylon depends entirely upon its agriculture. Its principal industry of this nature, other than the rice, coconut and fruit produced by the indigenous population, was coffee planting, introduced by British planters shortly after 1815. The bulk of the coffee was cultivated on estates under European man agement and financed by European capital, but considerable quantities were also grown by the indigenous population. To wards 1880 the coffee then covering vast areas, principally in the hill-country, was stricken by leaf-disease. Cinchona and other crops were tried as a substitute, and eventually tea. In a couple of decades it had equalled, and presently outstripped, the coffee industry, and even at the present time, when many of the low lying tea-estates have been converted into rubber plantations, it covers a larger area than was ever under coffee. Rubber was in troduced during the closing years of the 19th century, and, unlike tea, has found great favour with Ceylonese agriculturists and capitalists. It to-day covers in the aggregate a larger area than tea. None the less, the principal native agricultural industries continue to be coconuts and rice. (H. CO This island was known to Brahmanical literature under the name of Lanka, to the Greeks and Romans as Taprobane, to the Mohammedan seamen and merchants, who for so long had a monopoly of the sea-borne trade of the Indian ocean, as Serendib, which it has been suggested is a corruption of the Sanskrit Sinhaladvipa, and to the Portuguese as Zeylan, from which is derived its modern name. The presumed aboriginal inhabitants of the island were the people to-day called Veddahs, a few of whom still occupy certain rock-shelters in the eastern Province of the island. A careful and scientific examination of these people was made in 1910 by Professor and Mrs. C. D. Seligman. Though their language is said to have certain Indian affinities, they seem ethnologically to be related to the rather lightly coloured, wavy haired race which is found surviving as somewhat the higher of the two principal aboriginal races in many parts of south-eastern Asia. The Veddahs are probably related to the Semang or Pangan of the Malay peninsula and the Andaman islanders. Of the latter race, however, no trace has ever been found in Ceylon. The Veddahs are regarded by the Sinhalese as of goigama—viz. husbandman—caste.

The great Hindu epic, the Ramayana, tells of the conquest of the greater part of the island by the hero Rama who, with his army, crossed Adam's bridge (q.v.) by the aid of the monkey god Hanurnan and his host, the object of his invasion being, as in the case of Menelaus, the recovery of his wife, Sita, who had been abducted by Rawana, king of Lanka. The invaders would appear to have penetrated deep into the heart of the massif which occupies the centre of the southern portion of Ceylon. Unlike most oriental countries, Ceylon can boast a written history of considerable antiquity, the Mahavansa. This chronicle tells of the landing of Vijaya, the first Sinhalese king, in 504 B.e., accom panied by a small band of Aryan-speaking followers who must, it is thought, have sailed from some point on the northern or north-eastern shores of the bay of Bengal, since the greater part of southern India has, from time immemorial, been inhabited by people of Dravidian stock. Vijaya married a local princess— quite possibly a Veddah—and is said to have become the king of all Ceylon. It is noteworthy that, until the Sinhalese had been driven from out the flat plains north of Dambulla by successive invaders from southern India, they appear never to have at tempted to populate at all densely the forest, which of old cov ered the hills and valleys of the central massif and the rich, moist areas in the plains immediately surrounding it. Instead, they established themselves throughout the vast, flat, arid country to the north of Dambulla, which extends to Puttalam on the west, to Kaikuda, some 2om. north-north-west of Batticalao, on the east, northward to Point Pedro in the Jaffna peninsula, and north west to Talaimannar. This country (Pihiti was its ancient name) they rendered capable of supporting a considerable population by the construction of one of the most elaborate irrigation-systems ever attempted by mankind. It may, however, safely be con cluded that Ceylon is to-day more thickly populated than it has been at any previous period of its history.

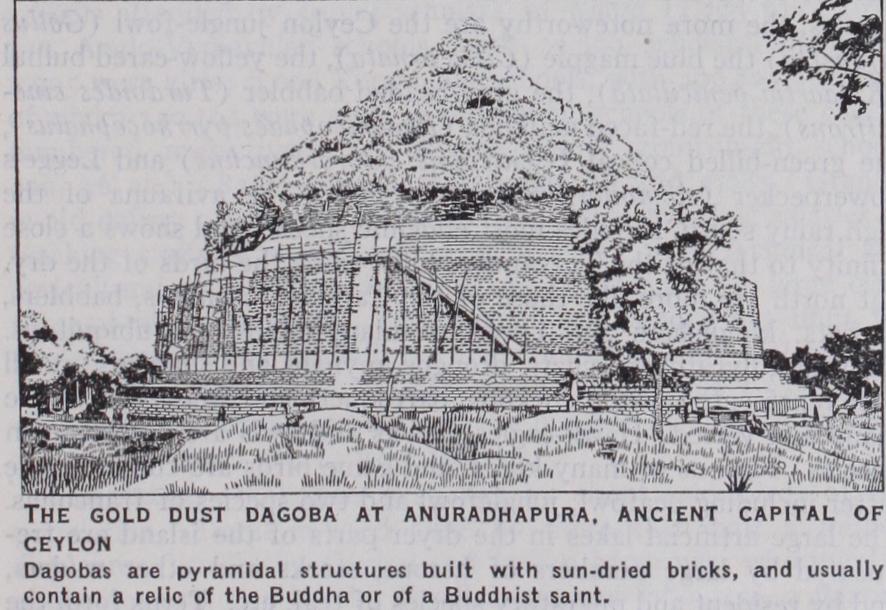

The Sinhalese kings had long been established at Anurad hapura, though their earliest capital was at Raja-Ratta, when in 307 B.C. the island was visited by Mahinda, a Buddhist priest and a son of Asoka, who is piously believed to have reached Mihintale from his father's capital, Magadha, accompanied by a few dis ciples, by levitation. A branch of the sacred Bo-tree, seated be neath the shade of which Gautama attained to Buddha-hood, was imported from Magadha and planted at Anuradhapura in 288 B.C.; it is therefore 2,200 years old. Tradition tells that Gautama him self visited Ceylon, in the course of his ministrations, on three occasions, the last descent being on Adam's peak (q.v.). Though he is said personally to have undertaken the instruction of the people, there is nothing to show that Buddhism won any foot hold in Ceylon until the beginning of the 3rd century B.C. From that time onward, however, up to the present time, it has been the religion to which the vast majority of Sinhalese adhere, though in Maka-Sen (A.D. 275) Ceylon had its Julian the Apostate, and its Messalina in queen Lila-Watti (A.D. 1202). Buddhism is es sentially a tolerant, non-proselytizing philosophical system, but it has assumed in Ceylon since 1912 an aggressive militant tone, borrowed from the most ignorant and tactless of Christian mis sionaries; and the peculiar imitative quality, which is so marked a Sinhalese characteristic, has displayed itself in this and in the establishment of young men's and women's Buddhist associa tions, etc. The word Mahavansa means The Genealogy of the Great and, as was to be expected, the priestly chroniclers, who wrote in Pali, a tongue not understood by the people, had nought to say about them. They also tell with apparent fidelity the long, tangled story of successive murderous strivings for the throne and of the frequent invasions of northern and central Ceylon by princes and armies of southern India, one of which led to the usurpation of the throne of Anuradhapura for a period by the Tamil Elala, who was slain by the Sinhalese kingly and saintly hero Dutegemunu (c. 190 B.c.). The ruins of Anuradhapura, as we know them to-day (they were buried in jungle and com pletely deserted and neglected until about 1845) are interest ing but disappointing, in that it is not easy to reconstruct from them any very vivid picture of the city in its prime. The upper structures were of timber, and all have long ago perished, leaving only the foundations for the instruction of archaeologists. The massive dagobas—the pyramidal structures which are veritable hills laboriously constructed of small sundried bricks—and some of the buildings of Polonnaruwa are in a somewhat better state of repair. Both these ancient capitals, which had for centuries been completely deserted and surrendered to the jungle by the Sinhalese, have become under British rule places of monthly pilgrimage to which hundreds of thousands of pious Buddhists annually resort. A great deal of archaeological and epigraphical work has been done during the last 5o years by the archaeological department established by Sir William Gregory (1872-77) ; but the history of Ceylon under its Sinhalese kings is mainly a chron icle of royal crimes, virtues and delinquencies; of the long drawn out struggle with invading princes and armies from southern India, and of internecine strife between the Sinhalese kings of Pihiti (viz., northern Ceylon) and the chiefs of Rohuna and Maya-Ratta, the two districts or provinces into which the then sparsely populated southern portion of the island was divided. The last great revival of the glory of Sinhalese monarchy took place under Prakrama Bahu who was crowned king of Pihiti in 11J3 at Polannaruwa, and in 1155 king of all Lanka, after suc cessful war against Rohuna. His reign is lovingly styled "The Golden Age of Lanka" by the past-praising Sinhalese of today ; but his wars, his invasion of Pegu in Burma and of the Pandyan country in southern India, his enormous activity as a builder of non-remunerative works, such as his palace with its reputed 4,000 apartments, dancing-halls, dagobas, monasteries and temples, as well as his construction and restoration of innumerable irrigation tanks, must have imposed an almost unendurable strain upon the energies of his subjects. Fanatically religious, he lavished land and treasure upon the priesthood, who repaid him by giving him in the Mahavansa a superhumanly excellent character; he per secuted ruthlessly heretical Buddhist sects, which by the hier archy was also accounted to him for righteousness; he endowed Brahmans, in a fine but hardly consistent, spirit of religious toleration ; and, in imitation of Asoka, he imposed vegetarianism upon his overwrought people, and punished with great severity the taking of animal life, either in the water or on the land. The people must have been reduced in large numbers to a condition indistinguishable from slavery, and it is certain that this great monarch did much to ruin his country economically by his im providence. Ceylon, or more properly Pihiti, had been conquered and annexed by Indian princes on several occasions, but in 1408, in revenge for an insult offered to an envoy a Chinese army invaded the island and carried King Vijaya Bahu IV. into cap tivity. For 3o years Ceylon remained tributary to China.

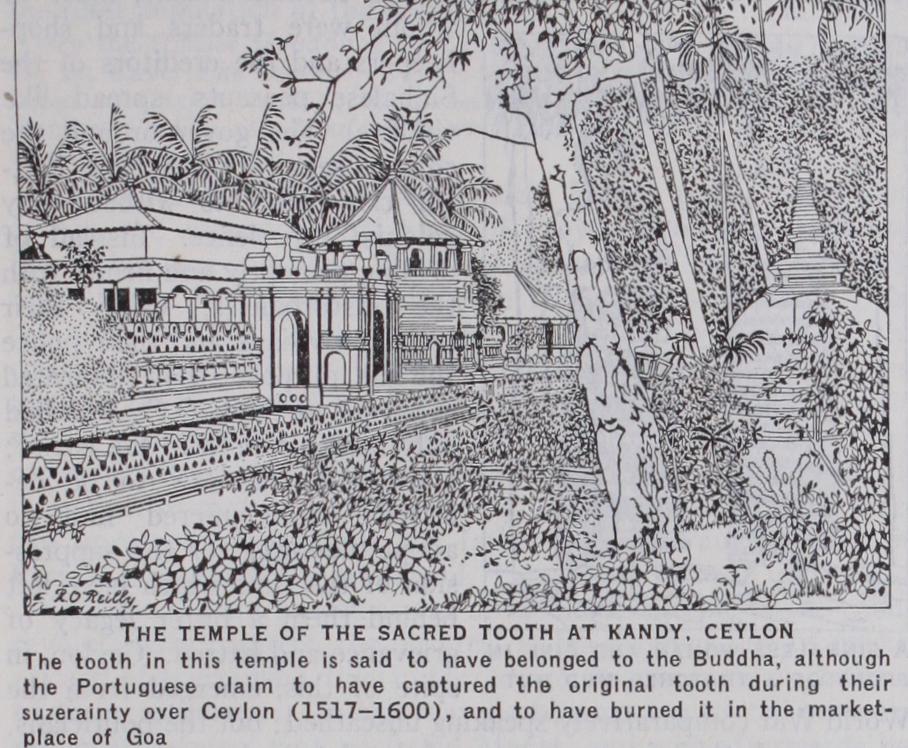

Ceylon was first visited by the Portuguese when Francisco de Almeida landed there in 1505. He found an island divided into seven kingdoms, each ruled by its separate monarch, and each frequently at odds with one or more of its neighbours. In 1517 a fort was erected at Colombo by orders of the viceroy at Goa, with the permission of the king of Cotta ; and from this time onward until the end of the 16th century the Portuguese were constantly at war with one or another of the native kingdoms. It is claimed that, when attacking and conquering Jaffna (Jaffna patam) they obtained possession of the Tooth relic and, in spite of the enormous ransom offered for it, publicly burned it in the market-place at Goa in obedience to the archbishop, who would not suffer the viceroy to make money out of the sale of what he accounted an idol. By the Sinhalese priesthood, who still possess a Tooth relic the shrine of which is at Kandy, it is asserted that the object captured at Jaffna was a false tooth. The Portuguese won a firm foothold on the western littoral, and they succeeded in converting the bulk of the karawa or fisher-caste Sinhalese to Christianity. Conversions upon a considerable scale, but almost invariably among the lower caste sections of the population, were similarly effected in other parts of the island; and at the 1921 census Christians numbered 443,40o, or nearly 1o% of the total population of Ceylon, more than 95% being Roman Catholics. The proselytizing fervour and cynical rapacity of the Portuguese won for them hosts of enemies among the natives of all ranks, while their inherited traditional hatred for the Moors—by which term they described all Mohammedans—rendered them peculiarly odious to the latter, whose trade and shipping monopolies they had destroyed. The French, the Dutch and the British, when in turn they set the Bull of Alexander VI. at defiance and forced their way into the Indian ocean, were accordingly welcomed as deliverers by the people of the East generally ; and the trading centres which they had established in the beginning with such dauntless courage, and where they had exploited and persecuted the native populations so ruthlessly, fell before the Dutch and the British, fighting often in alliance with native potentates.

The Dutch admiral Spilberg landed on the east coast of Ceylon in 1602 and was welcomed by the king of Kandy who besought him to help in the ejection of the hated Portuguese. No action of importance was taken, however, until 1638-39, when a Dutch expedition attacked and destroyed the Portuguese forts on the east coast. In 1644 Negombo, which had once before been unsuc cessfully attacked, fell to the Dutch; and in 1656 and 1658 Colombo and Jaffna were successively captured. The Dutch thus became masters of practically the whole of the maritime prov inces of Ceylon, the kingdom of Kandy alone retaining its inde pendence. The Dutch forthwith set about the task of the method ical and efficient administration of the country in a fashion never attempted by the Portuguese. They taxed the people heavily, but the land-registers which they instituted have endured to this day, as also has Roman-Dutch law, many of the provisions of which are now deeply ingrained in the traditions of the Low Country Sinhalese peasantry and landholders. They also under took public works upon a considerable scale; built excellent houses for their own accommodation, public offices, law courts and churches, many of which still survive; and the roads which they made opened up the interior and greatly stimulated the trade of the island. Tolerant to Buddhism, Hinduism and Mohammedan ism, they persecuted the Catholics persistently, but the religion which had been acquired by thousands of Sinhalese and by the Ceylon-born Tamils of Jaffna and Mannar was too deeply rooted in the peoples' hearts for its extirpation to be possible. Through out the Dutch period Kandy maintained its independence.

The British, who had dispatched an embassy to the king of Kandy from Madras as early as 1763 without result, after various naval skirmishes in the neighbourhood of Trincomalee and Bat ticalao, sent a well equipped force against the Dutch in Ceylon in 1795, met with only a feeble resistance and in less than a year had obtained possession of the island. The Dutch rule had lasted for about 140 years, a period equal to that of Portuguese domina tion ; but while the latter left Ceylon more distracted and no more developed than they had found it on their arrival, the Dutch administration, if somewhat harsh, and unimaginative, worked genuine and permanent improvement in almost every branch of the social and economic life of the people. The Dutch practice, followed by them for so long in almost all their overseas posses sions, of taking over oppressive local systems of taxation, which had only been endurable because evasion was so common, and thereafter applying them with ruthless efficiency, made their rule highly unpopular ; and even to-day the Burgher population, who are the descendants of the former Dutch rulers and settlers, are far from being loved by the Sinhalese. These Ceylonese Dutch men, though many of their families have dilutions of oriental blood in their veins have retained their national character, their sturdy self-esteem, their traditions and high ideals of probity and conduct in a very remarkable degree. Until quite recently they had a practical monopoly of the clerical work in most public departments, and held most positions of trust in public depart ments and commercial houses.

At first Ceylon was administered from Madras, but an attempt to apply the Madras revenue system and the employment of a host of Malabar collectors led to a rebellion, and in 1798 Ceylon became a Crown colony. The Treaty of Amiens (1802) formally ceded Ceylon to Great Britain ; and the following year Kandy was invaded and occupied. The garrison was shortly afterward treach erously massacred after it had been induced to lay down its arms. It was not till 1815, however, that the Kandyan chiefs (with some of whom at an earlier period governor North had carried on dis creditable intrigues against their king) invoked the aid of the British to rid themselves of this tyrant of Malabar stock whose cruelties had surpassed endurance. The Kandyan kingdom was thus voluntarily handed over to the British Crown which guar anteed its people civil and religious liberty and the maintenance of their ancient customs. An insurrection which broke out shortly after was easily suppressed, and the second treaty (1818) which followed it did not materially alter in any respect the status of the Kandyan chiefs and people vis-a-vis the Crown. The pacifica tion and opening up of the mountain country by the construction of roads led immediately to a great incursion of Low Country Sinhalese, Mohammedan and Hindu traders, and European coffee planters. These latter penetrated into the virgin forest and, aided in the task of clearing by the Sinhalese villagers, carved out estates for themselves. The indigenous inhabitants declined to work for a wage on the European estates, save as artisans, etc., and it was found necessary to import as voluntary immigrants large numbers of Tamil coolies from the arid districts of southern India. Attempts to introduce cinchona were only partially suc cessful, but very soon tea began to be planted and by the end of the century it was covering a far larger area than coffee had ever done. Then came rubber-planting, an enterprise in which, for the first time, Sinhalese planters took an active part, their energies having in the past been confined to the cultivation of coffee, which ended in disaster, to some cocoa-planting and to coconut-planting, which was and still is the major Ceylonese native agricultural industry. Large fortunes were also made by Ceylonese in plumbago mining. The consequent acquisition of wealth by the natives of Ceylon, and especially by men of the karawa caste, brought about a social upheaval, and led to an agitation for political reform, the real object of which (though stimulus was imparted to it by the Morley-Minto reforms in British India) was to break the monopoly which the highest caste goigama aristocracy had till then enjoyed of representing Sinhalese interests in the legislative council. During the agitation that preceded the granting of these claims, ill-feeling based on caste prejudice and upon the angry passions which such prejudice aroused, and racial animosity began for the first time to become vocal in Ceylon. The first scheme of reform was worked out in 19o9 by Col. Seely, then under-secretary of State for the Colonies, and accepted by governor McCallum, in spite of the protests of his executive councillors and the obvious inapplicability of Seely's scheme as originally framed by him to local circumstances. The first election of a representative of the educated Ceylonese was fought purely on caste lines, a high caste Tamil being chosen with the aid of the high caste Sinhalese vote, caste prejudice thus proving to be a stronger passion than racial bias. A state of growing unrest was thus created, and this was increased by the outbreak of the World War. In 1915 a religious fracas at Gampola, between the Buddhists and Mohammedans, most of whom were traders and shop keepers and the creditors of the Sinhalese peasants, spread like wildfire. The governor and the colonial secretary were both Brit ish civil servants without any colonial experience. Instead of dealing promptly and firmly with the disturbances, using their trained civilians and their police for the purpose, they abdicated in favour of the G.O.C., who had only been a month in the island; allowed martial law to be de clared; and suffered him to adopt measures for the suppres sion of the riots which have left behind them a bitter legacy of grievance and hatred. Ceylon, in spite of this, emerged from the World War comparatively speaking unscathed ; but the politicians, whose hands the mismanagement of the riots had greatly strength ened, had tasted of success, and during the governorship of Sir William Manning (1918-25) a series of legislative reforms were granted in rapid succession, the final instalment in 1924 definitely vesting all financial control in the hands of 36 unofficial members, three of whom only are Europeans and the majority of whom are elected, the officials upon the legislative council numbering only and meetings being ordinarily presided over by an elected Ceylonese vice-president. In the meantime three unofficial Cey lonese (two Sinhalese and one Tamil) and one European had been added to the executive council. Responsibility for the good ad ministration of the island continued, none the less, to be vested solely in the governor, who is unable to discharge it save by the good will of the unofficial majority in the legislative council or by the exercise of his power of veto, which can easily be count ered by a refusal to vote supply—action which would necessitate the practical suspension of the constitution. An appreciation of the impracticability and of the dangers of this situation caused the present writer while serving as governor of Ceylon (Nov. 1925 to June 1927), after a year of study, to recommend the appoint ment of a commission to examine the situation and to report as to the measures that could be best taken to surmount the impasse.

The special peculiarity of the political situation in Ceylon is that this small island contains a very heterogeneous population; that the Low Country Sinhalese number about 2,000,000, the Kandyans 1,000,000, the Ceylon-born Tamils about 500,000, Indian-born Tamils, most of them coolies on tea and rubber estates, about 600,000, Ceylon-born Moors 250,000, Indian-born Moors 33,000, Burghers and Eurasians about 30,000, and Euro peans slightly more than 8,000. The Low Country Sinhalese, who are more sophisticated than the Kandyans, more diligent and more wealthy, have long ago spread themselves throughout the Kandyan provinces, claim, as Buddhists, a share in the manage ment of Kandyan Temporalities, and are at pains to explain that the Sinhalese, or even the "Ceylonese," nation is one and indivisible. The Kandyans, on the other hand, who mark the peaceful but very lucrative penetration of their country by Low Country Sinhalese with dislike, remember that these folk aided the Portuguese, the Dutch and the British in their several attacks on the Kandyan kingdom and, knowing themselves to be at once outnumbered and outmatched by them view any system of gov ernment that places the supreme power in the hands of a majority with acute apprehension. These feelings are in some degree shared by the Ceylonese Tamils, though in their case it is they who in vade the country occupied by Low Country Sinhalese and, by superior energy, diligence and frugality, are rapidly underselling them in clerical and similar employment. They have no desire, however, to see the island ruled by a Low Country Sinhalese majority. The Burghers are still more apprehensive; while the Europeans, who represent huge financial interests, alike in the world of commerce and in agricultural enterprise, are only .156 of the total population of the island. (H. CO See the Official Handbook of Ceylon (1924) and various annuals; H. W. Cave, The book of Ceylon (1912) ; G. E. Mitton, The Lost Cities of Ceylon (1916) ; R. L. Spittel, Wild Ceylon (1925) ; A. F. Toulba, Ceylon, the Land of Eternal Charm (1926) ; F. M. Trautz, Ceylon (Berlin, 1926) .