Chair

CHAIR, a movable seat, usually with four legs and for a single person, the most varied and familiar article of domestic furniture. (In Mid. Eng. cliaere, through O.Fr. chaere or cliaiere, from Lat. cathedra, later caledra, Gr. rca9S3pa seat, cf. "cathe dral" ; the modern Fr. form chaise, a chair, has been adopted in English with a particular meaning as a form of carriage ; chaise in French is still used of a professorial or ecclesiastical "chair," or cathedra.) The chair is of extreme antiquity, although for many centuries and indeed for thousands of years it was an ap panage of state and dignity rather than an article of ordinary use. "The chair" is still extensively used as an emblem of author ity. It was not until the i6th century that it became common anywhere. The chest, the bench and the stool were until then the ordinary seats of everyday life, and the number of chairs which have survived from an earlier date is exceedingly limited; most of such examples are of ecclesiastical or seigneurial origin.

Ancient Chairs.

In ancient Egypt they were of great rich ness and splendour. Fashioned of ebony and ivory, or of carved and gilded wood, they were covered with costly stuffs and sup ported upon representations of the legs of beasts of the chase (li the figures of captives. The earliest monuments of Nineveh repre sent a chair without a back but with carved legs ending in lions' claws or bulls' hoofs; others are supported by figures in the nature of caryatides or by animals. The earliest known form of Greek chair, going back to five or six centuries before Christ, had a back but stood straight up, front and back. On the frieze of the Parthenon Zeus occupies a square seat with a bar-back and thick turned legs ; it is ornamented with winged sphinxes and the feet of beasts. The characteristic Roman chairs were of marble, also adorned with sphinxes; the curule chair was originally very similar in form to the modern folding chair, but eventually received a good deal of ornament.The most famous of the very few chairs which have come down from a remote antiquity is the reputed chair of St. Peter in St. Peter's at Rome. The wooden portions are much decayed, but it would appear to be Byzantine work of the 6th century, and to be really an ancient sedia gesta toria. It has ivory carvings rep resenting the labours of Hercules. A few pieces of an earlier oaken chair have been let in ; the exist ing one, Gregorovius says, is of acacia wood. The legend that this was the curule chair of the sena tor Pudens is necessarily apoc ryphal. It is not, as is popularly supposed, enclosed in Bernini's bronze chair, but is kept under triple lock and exhibited only once in a century.

Byzantium, like Greece and Rome, affected the curule form of chair, and in addition to lions' heads and winged figures of Victory and dolphin-shaped arms used also the lyre-back which has been made familiar by the pseudo-classical revival of the end of the 18th tury. The chair of Maximian in the cathedral of Ravenna is believed to date from the middle of the 6th century. It is of marble, round, with a high back, and is carved in high relief with figures of saints and scenes from the Gospels—the Annunciation, the Adoration of the Magi, the flight into Egypt, and the baptism of Christ. The smaller spaces are filled with carvings of animals, birds, flowers and foliated ornament. Another very ancient seat is the so-called "Chair of Dagobert" in the Louvre. It is of cast bronze, sharpened with the chisel and partially gilt ; it is of the curule or faldstool type and supported upon legs terminating in the heads and feet of animals. The seat, which was probably of leather, has disappeared. Its attribution depends entirely upon the statement of Suger, abbot of St. Denis in the 12th century, who added a back and arms. Its age has been much discussed, but Viollet-le-Duc dated it to early Merovingian times.

To the same generic type be longs the famous abbots' chair of Glastonbury ; such chairs might readily be taken to pieces when their owners travelled. The f ald isterniuna in time acquired arms and a back, while retaining its folding shape. The most famous, as well as the most ancient, Eng lish chair is that made at the end of the 13th century for Edward I., in which most subsequent monarchs have been crowned. It is of an architectural type and of oak, and was covered with gilded gesso which long since disappeared.

Transition.

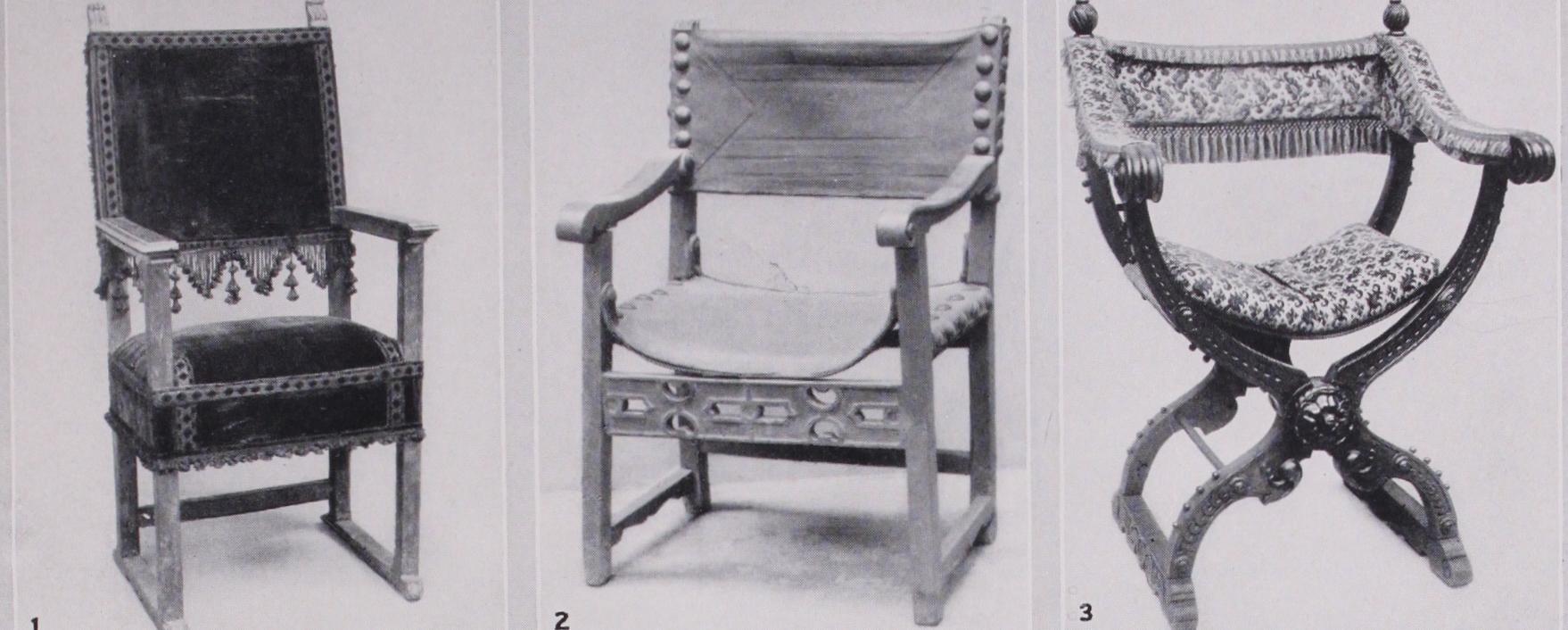

Passing from these historic examples we find the chair monopolized by the ruler, lay or ecclesiastical, to a com paratively late date. As the seat of authority it stood at the head of the lord's table, on his dais, by the side of his bed. The sei gneurial chair, commoner in France and the Netherlands than in England, is a very interesting type, approximating in many re spects to the episcopal or abbatial throne or stall. It early acquired a very high back and sometimes had a canopy. Arms were in variable, and the lower part was closed in with panelled or carved front and sides—the seat, indeed, was often hinged and sometimes closed with a key. That we are still said to sit "in" an arm-chair and "on" other kinds of chairs is a reminiscence of the time when the lord or seigneur sat "in his chair." These throne-like seats were always architectural in character, and as Gothic feeling waned took the distinctive characteristics of Renaissance work. It was owing in great measure to the Renaissance that the chair ceased to be an appanage of state, and became the customary com panion of whomsoever could afford to buy it. Once the idea of privilege faded the chair speedily came into general use, and almost at once began to reflect the fashions of the hour. No other piece of furniture has ever been so close an index to sumptuary changes. It has varied in size, shape and sturdiness with the fashion of women's dress as well as men's. Thus the chair which was not, even with its arms purposely suppressed, too ample during the several reigns of some form or other of hoops and farthingale, became monstrous when these protuberances disappeared. Again, the costly laced coats of the dandy of the i8th and early 19th centuries were so threatened by the ordinary form of seat that a "conversation chair" was devised, which enabled the buck and the ruffler to sit with his face to the back, his valuable tails hang ing unimpeded over the front. The early chair almost invariably had arms, and it was not until towards the close of the i6th century that the smaller form grew common.

The 17th Century.

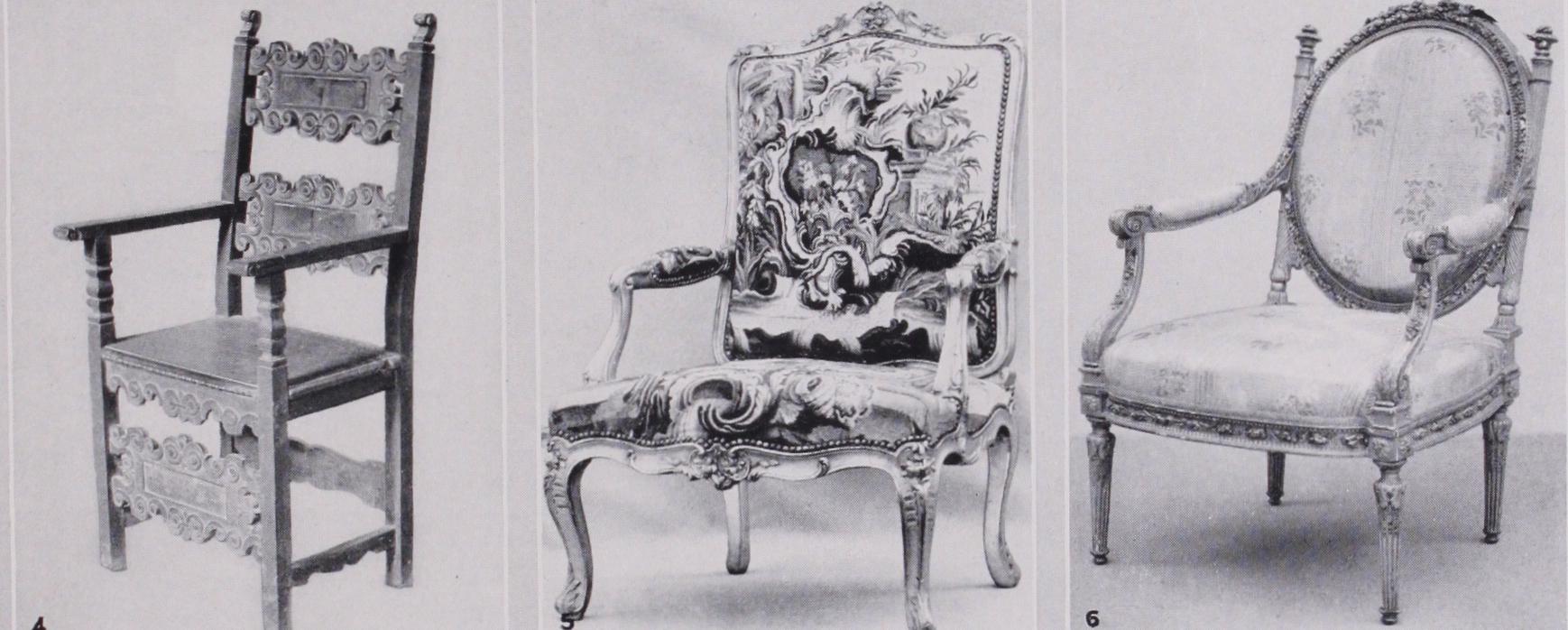

The majority of the chairs of all countries until the middle of the 17th century were of oak without uphols tery, and when it became customary to cushion them, leather was sometimes employed ; subsequently velvet and silk were exten sively used, and at a later period cheaper and often more durable materials. Leather was not infrequently used even for the costly and elaborate chairs of the faldstool form—occasionally sheathed in thin plates of silver—which Venice sent all over Europe. To this day, indeed, leather is one of the most frequently employed materials for chair covering. The outstanding characteristic of most chairs until the middle of the i 7th century was massiveness and solidity. Being usually made of oak, they were of considerable weight, and it was not until the introduction of the handsome Louis XIII. chairs with cane backs and seats that either weight or solidity was reduced. Although English furniture derives so ex tensively from foreign and especially French and Italian models, the earlier forms of English chairs owed but little to exotic influences.This was especially the case down to the end of the Tudor period, after which France began to set her mark upon the British chair. The squat variety, with heavy and sombre back, carved like a piece of panelling, gave place to a taller, more slender, and more elegant form, in which the framework only was carved, and attempts were made at ornament in new directions. The stretcher especially offered opportunities which were not lost upon the cabinet-makers of the Restoration. From a mere uncompromising cross-bar intended to strengthen the construction, it blossomed into an elaborate scroll-work or an exceedingly graceful semi circular ornament connecting all four legs, with a vase-shaped knob in the centre. The arms and legs of chairs of this period were scrolled, the splats of the back often showing a rich arrange ment of spirals and scrolls. This most decorative of all types appears to have been popularized in England by the cavaliers who had been in exile with Charles II. and had become familiar with it in the north-western parts of the European Continent.

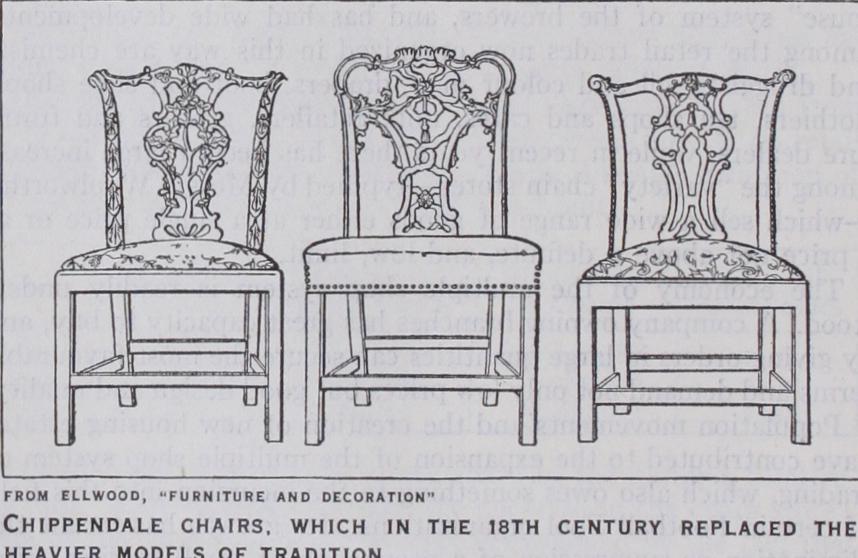

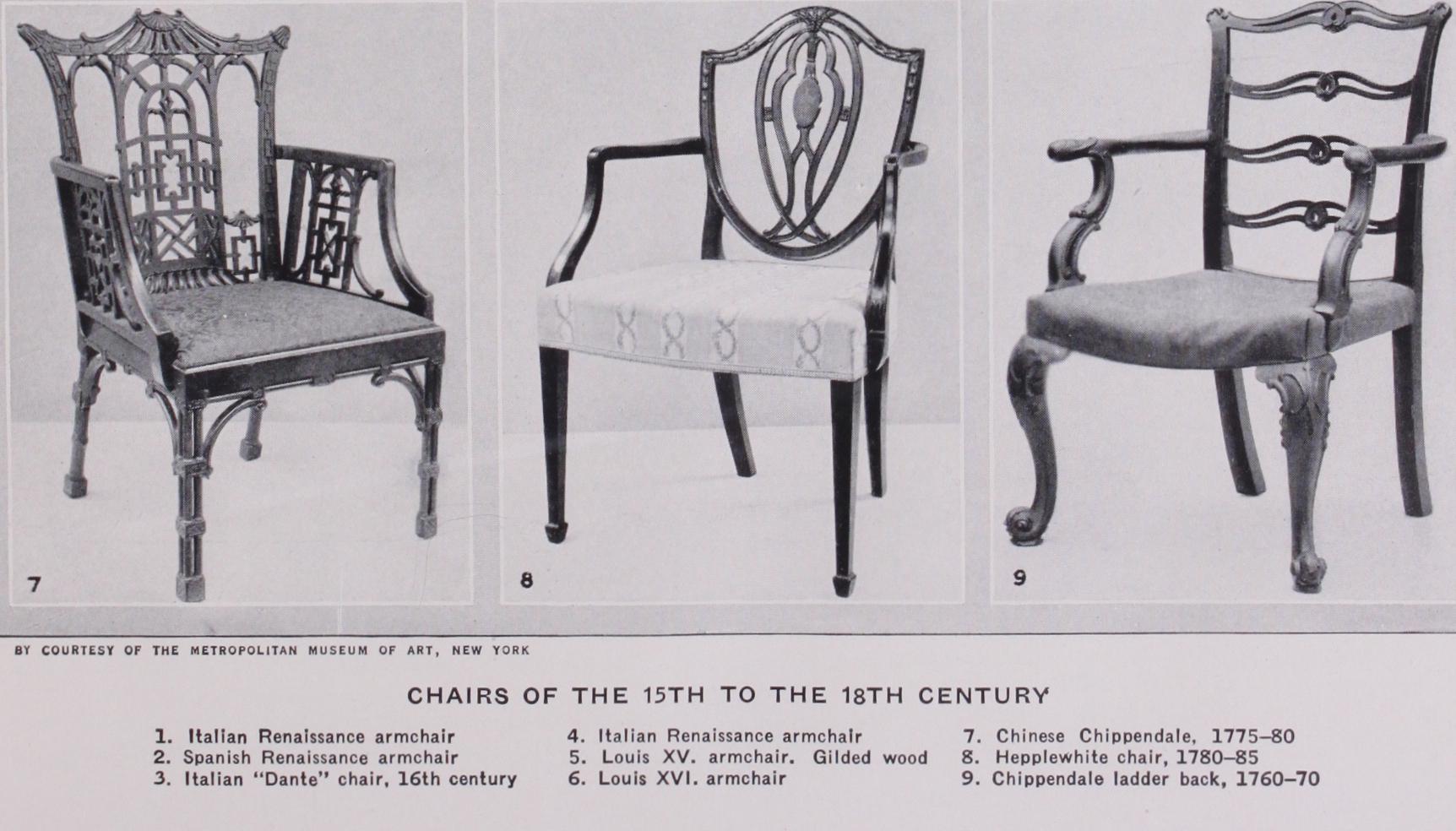

During the reign of William and Mary these charming forms degenerated into something much stiffer and more rectangular, with a solid, more or less fiddle-shaped splat and a cabriole leg with pad feet. The more ornamental examples had cane seats and ill-proportioned cane backs. From these forms was gradually de veloped the Chippendale chair, with its elaborately interlaced back, its graceful arms and square or cabriole legs, the latter terminating in the claw and ball or the pad foot. Hepplewhite, Sheraton and Adam all aimed at lightening the chair, which, even in the master hands of Chippendale, remained comparatively heavy. The endeavour succeeded, and the modern chair is every where comparatively slight. Chippendale and Hepplewhite be tween them determined what appears to be the final form of the chair, for since their time practically no new type has lasted, and in its main characteristics the chair of the loth century is the direct derivative of that of the later i8th.

The i8th century was, indeed, the golden age of the chair, es pecially in France and England, between which there was con siderable give and take of ideas. Diderot could not refrain from writing of them in his Encyclopedie. The typical Louis Seize chair, oval-backed and ample of seat, with descending arms and round-reeded legs, covered in Beauvais or some such gay tapestry woven with Boucher or Watteau-like scenes, is a very gracious object, in which the period reached its high-water mark. The Empire brought in squat and squabby shapes, comfortable enough no doubt, but entirely destitute of inspiration. English Empire chairs were often heavier and more sombre than those of French design. Thenceforward the chair in all countries ceased to at tract the artist. The art nouveau school has occasionally produced something of not unpleasing simplicity; but more often its efforts have been frankly ugly or even grotesque. There have been prac tically no novelties. So much, indeed, is the present indebted to the past in this matter that even the revolving chair, now so familiar in offices, has a pedigree of something like four centuries (see also INTERIOR DECORATION; FURNITURE). (J. P.-B.)