Chemical Warfare

CHEMICAL WARFARE. The use of irritant and poison ous substances to diminish the resistance of an opponent is prob ably as old as organized warfare. Thucydides describes two instances of the use of burning sulphur and pitch in sieges in the Peloponnesian War, and throughout classical times and the middle ages such methods were frequently employed, Greek fire being a device of this kind. As war became more mobile and the range of actions increased, the opportunities for using such a weapon in its primitive form disappeared, but in 18S5 Lord Dundonald proposed a scheme for burning sulphur on a large scale under favourable wind conditions in order to reduce the Malakoff work during the siege of Sebastopol. The suggestion was rejected on the ground of inhumanity.

International Law.

The use of toxic substances was fore seen at The Hague Peace Conference of 1899, when the govern ments represented pledged themselves not to use any projectiles the sole object of which was the diffusion of asphyxiating or harmful gases. At The Hague Convention of i 9o7 the following rule was adopted : "It is expressly forbidden (a) to employ poison or poisoned arms, (b) to employ arms, etc., of a nature to cause unnecessary suffering." It has been argued that toxic gases were not contemplated as coming within the scope of this clause; but this was not the interpretation put on it by most of the Powers, and the Treaty of Versailles assumed that their use in any form was contrary to international law. This view was confirmed by the nations represented at the Washington Conference in 1922.

Gas in the World War.

At the outbreak of war none of the combatant nations had made any preparation for the use of gas or were equipped with any defence against it ; but, after the failure of the initial German attack and the development of trench warfare, means were sought by the Germans to assist the artillery preparation for an offensive against entrenched positions, in order to get back to a state of open warfare again. Proposals to use gas were made at an early date and on Oct. 27, 1914, shrapnel containing an irritant substance (dianisidine chlor sulphonate) were used by the Germans at Neuve Chapelle with out, however, any success. They were followed by shell con taining a strong lachrymator (xylyl bromide) in place of part of the charge of high explosive, which were used on the Russian front in Jan. 1915, when the low temperature made the lachry mator ineffective.The introduction of gas as an effective weapon in modern war fare really dates from April 22, 1915, when the Germans dis charged chlorine from cylinders on a front of about 4 m. at Lange marck opposite a sector held by the French. The effect of the discharge, which came as a complete surprise, against unpro tected troops was to eliminate for a depth of several miles all re sistance on the front affected. A similar attack was made on the Canadian front near Langemarck on April 24. Owing to various reasons the Germans failed to take advantage of the opportunity offered by these first attacks for a decisive stroke, and within a few days the Allied troops were equipped with a crude form of respirator and the immediate danger was over. The Germans soon found considerable difficulties in combining an infantry attack with a cylinder discharge which was dependent on a favourable wind. Consequently they abandoned the cloud gas attack except as a means of inflicting casualties on the Allies. From Dec. 1915 their cloud attacks became more dangerous owing to the admix ture of an increasing amount of phosgene with the chlorine, which added greatly to its toxicity, but of course the protection of the Allies was improving at the same time.

The Allies were quick to adopt retaliatory measures : the first British gas attack was made at Loos on Sept. 25, 1915, with cylin ders of chlorine, and from then to the end of the war frequent cloud discharges were made, as the wind was more often favour able to the Allies than to the Germans.

As a weapon for use in an attack the gas shell offers great ad vantages over the cloud discharge, as it allows the use of a much greater variety of toxic substances and its employment is indepen dent of the wind. The Germans scored one success with lachry matory shell in the Argonne in July 1915, but the French were the first to realize the possibilities of a gas shell filled with a highly toxic gas such as phosgene, with a small bursting charge just sufficient to open the shell. The French shell of this type surprised the Germans in the spring of 1916 and was of considerable assist ance in the defence of Verdun. Subsequently the Germans modi fled their gas shell to the same type and made considerable use of them both at Verdun and in the Somme battle.

Gas in 1917.

In this year gas shell first became a serious factor in the tactical situation, as both the Allies and the Germans had provided themselves with considerable quantities as a result of their experience in 1916. The German shell contained mainly trichlormethyl chloroformate and chlorpicrin, toxic substances of a semi-persistent nature ; the French phosgene, or prussic acid; the British chlorpicrin or lachrymators. Gas shells were used mainly during active operations for neutralizing the enemy's bat teries, for interfering with the movements of troops, and for general harassing purposes. By firing gas shells it was always possi ble to compel the wearing of a respirator and, especially at night, this resulted in a considerable diminution of efficiency. Also sudden bursts of lethal shell were fired at targets known to be occupied in order to produce casualties by surprise before respirators had been adjusted. In order to achieve this it was necessary to set up suddenly a high local concentration of gas, and the most effective weapon for this purpose was the Livens Projector, first used at Arras in March 1917. This was a crude form of trench mortar, firing a bomb weighing 6o lb. and containing 3o lb. of phosgene. Large numbers could be installed together and fired simultaneously at the same target, producing very high concentrations of gas with out any warning beyond the flash and noise of the discharge and the bursting of the bombs. The projector became one of the deadliest weapons of those used in trench warfare.July 1917 is notable for the introduction of two new gases by the Germans, who had seen that, with the improved methods of protection, gases such as those mentioned above, which all betray their presence at once by their immediate irritant action on the eyes and respiratory tract, were losing much of their value. They therefore introduced two new substances, dichlorethyl sulphide, commonly known as "mustard gas," from its smell, or as "Yperite," from the place where it was first used and diphenyl chlorarsine. Mustard gas was the most effective agent used in chemical warfare and it was responsible for the majority of gas casualties. Owing to its slight smell it is less easily detected than other gases; and, although it produces no immediate sensations of discomfort, exposure to a very low concentration is sufficient to put a man out of action, owing to the effects of the gas on the eyes and lungs. As the liquid has a low vapour pressure at atmos pheric temperature and reacts very slowly with water, it may remain for days or weeks in the soil and continue to produce a dangerous concentration of gas wherever the temperature is high enough. In addition to its effects on the eyes and lungs, serious blisters are produced either by splashes of the liquid or by con tact with ground or any object contaminated by it.

Diphenylchlorarsine, a solid melting at 46° C, when finely di vided in the air causes sneezing, irritation and intense pain in the nose and throat, and nausea. There is a slight delay in the onset of the symptoms. Bottles of this substance are embedded in high explosive shell, so that on the burst of the shell it is scat tered as a fine dust in the air. Unless respirators are provided with a special form of filter they may be penetrated by these small par ticles, and the resulting sneezing may compel the removal of the respirator. However, this did not occur in the field of battle.

Gas in 1918.

For their offensive in 1918 the Germans made great use of gas shell, on which they relied to produce rapid neu tralization of the Allied artillery, thus enabling them to reduce the length of their preliminary bombardment to a few hours with out previous registration. As much as 8o% of gas shell was allotted for some tasks. The gas shell available at this date can be divided into two classes, from the point of view of tactical employment in an attack : (1) Shell containing liquids such as mustard gas, which may persist for long periods in the soil and cannot be used on ground which it is intended to attack or occupy.(2) Shell containing volatile liquids such as phosgene or diphos gene, or non-volatile solids such as diphenyichlorarsine, which owing to their low persistence may be used immediately before an attack.

The Germans used shell of the first class on the flanks of the attack and in other sections of the front to produce casualties, while the preliminary bombardment before each attack was mainly with gas shell of the second class, which compelled the continuous wearing of the respirator and added greatly to the strain and fatigue of the troops and interfered with movement and communication. The weather conditions in each offensive were suitable for gas shell except on July 15, when the attack failed. The Allies also were using large quantities of gas shell in 1918, including mustard gas after June, and so effective had they proved for various tasks that the proportion of gas shell was steadily increasing. It is noteworthy that no gas was used in naval actions during the World War, or from aircraft.

Gas As a Weapon.

The use of gas has added many compli cations to war. It compels all troops to carry a respirator, in volving additional weight of equipment and training. The pres ence of gas compels the wearing of the respirator, thereby reduc ing a soldier's efficiency by the interference with vision, speech, etc., and by the added fatigue, and the respirator cannot be worn for long periods without arrangements which admit of eating and drinking. Also the possibility of a gas attack increases the strain on troops both by the constant watchfulness that is necessary and the moral effect of gas, which cannot be neglected.Gas accounted for a moderate proportion of the casualties in the War. During the last year of the war 16% of the British and 33% of the American casualties were due to gas, but its tactical value cannot be judged by casualties alone; it proved invaluable in the neutralization of artillery, interference with movement, and hampering communication. Also, by the use of a persistent gas like mustard gas, it was possible to make a position Types of Gas Used.—The gases used in war can be classified roughly as follows, according to the predominant effect which they produce on the body, although many gases may belong to more than one class :— (I) Acute lung irritants, e.g., chlorine and phosgene, which exert an intense irritant action on the respiratory organs leading to acute pulmonary oedema.

(2) Lachrymators (tear-gas), e.g., xylyl bromide, which even in low concentrations make vision impossible by their irritant action on the eyes, although the effect may not continue.

(3) Paralysants, e.g., prussic acid, which in sufficiently high concentration cause death almost instantaneously by their effect on the nervous system.

(4) Sensory irritants of the eyes, nose and upper respiratory passages (also called sternutators as they often cause sneezing), e.g., diphenylchlorarsine ; these are often effective in very low concentrations, causing intense pain in the eyes, nose and throat, nausea, and subsequent depression.

(5) Vesicants, e.g., mustard gas, which cause inflammation and blistering of the skin, eyes and respiratory tract, the effect being produced as a rule some hours after exposure.

Broadly speaking, the gases in groups (1) and (3) may be regarded as lethal agents, those in groups (2) and (4) as putting a man out of action immediately, though temporarily, while the vesicants are delayed in action but have a great casualty produc ing power, even when used against troops trained in defensive measures.

The following tables give the principal gases used in the World War, with a brief summary of their important characteristics:— untenable except at the cost of heavy casualties; this occurred at Bourlon Wood in Nov. 1917 and at Armentieres in April 1918. In such ways gas proved itself a valuable auxiliary to existing weapons. Again, a heavy gas would penetrate into the deepest dugout which was immune against high explosive or shrapnel, and gas shell might be effective without getting a direct hit, as the gas from each burst to the windward of a target would drift over it. And, above all, gas always carries with it the possibility of surprise, the importance of which is considerable in any kind of warfare.

Methods of Liberating Gases.

The method selected for liberating gas depends partly on the object to be attained and partly on the physical properties of the gas.Gas can be discharged : (1) from cylinders as cloud gas; (2) from projectiles, e.g., shell, trench mortar bombs, or pro jectors, either as a true gas or in the form of liquid drops or as a fine dust; (3) from aeroplane bombs as from other projectiles; (4) as a spray from containers carried in aeroplanes or tanks.

Cylinder or cloud gas attacks were made by installing a large number of steel cylinders containing compressed gas in the front line trenches and discharging these in a suitable wind so that the gas was carried over into the enemy's trenches. The gas used must be denser than the air so that it does not rise when discharged, and it must be at a sufficient pressure to ensure that the contents of the cylinders are discharged rapidly when the valves are released. Chlorine and mixtures of chlorine and phosgene were employed mainly for this purpose. Gas projectiles contain a toxic substance and a bursting charge, and the effect on burst depends on the nature of the filling and the size of the burster.

A volatile substance like phosgene forms a small cloud which drifts with the wind, while with a liquid like mustard gas part of the filling is dispersed as a cloud, but a considerable proportion will be scattered over the ground in or near the shell crater and may continue to give off a dangerous concentration of vapour for days. A solid such as diphenylchlorarsine is dispersed as a cloud of fine dust which drifts down wind leaving no persistent effect. Similar results are obtained with aeroplane bombs. Liquids can be sprayed either from tanks or aeroplanes, but in the latter case there may be considerable losses by evaporation if the drops have to fall from a great height.

Protection Against Gas.

Like all other weapons gas has its antidote. This takes the form of a respirator which filters out toxic materials from the air before it reaches the lungs. The early patterns consisted of a pad of cotton waste, dipped in a solution of sodium thiosulphate and sodium carbonate, which was tied over the mouth. This was replaced by flannel or flannelette helmets, dipped in various solutions, which were worn over the head and protected the eyes as well as the lungs. The measure of protection obtainable by such means is obviously very limited, and the use of a general absorbent such as charcoal has many advan tages to offer. All the combatants in the World War finally adopted respirators in which the inspired air was filtered by passing through activated charcoal in a small container, with various admixtures of other substances to increase the protection against specific gases. Pads of cellulose or other filtering material were added to give protection against the fine particles produced by the explosion of shell containing such substances as diphenyl chlorarsine. The container was attached directly to an imper meable facepiece held in position by elastic bands over the head so as to make an airtight joint round the face, as in the German, respirator, or it was carried in a haversack and connected to the facepiece by a rubber tube carrying a mouthpiece, as in the British Box Respirator, in which case it was necessary to prevent breathing through the nose by a nose-clip attached to the face piece. In the French respirator, which resembled the German, the inspired air passed over the glass eyepieces and prevented the depositions of moisture on them, thus securing clear vision.The ideal respirator represents a compromise between safety and military efficiency. Its weight must be small, it must admit of easy carriage and rapid adjustment, and offer little resistance to breathing; also it must be comfortable to wear and interfere as little as possible with vision and hearing. At the same time it must give a sufficient measure of protection against all gases likely to be encountered in the field.

But the respirator alone is no guarantee of safety; the soldier must be able to recognize the presence of gas by its smell or other effects, and thus know when he needs protection. Also he must be trained to carry out his duties while wearing a respirator for long periods so as to suffer the minimum loss of efficiency.

Apart from these measures of individual protection, there are a number of precautions which may be grouped together under the heading of collective protection. These include arrangements for giving the alarm in case of a gas attack, the provision of pro tected shelters in which men can remain during a gas attack with out wearing respirators, or to which they can go to eat or drink, and the clearing of gas and the decontamination of ground after a gas attack of any kind.

Future of Chemical Warfare.

After the experience of the war there is a general feeling that gas may figure again in some future war in spite of international agreements, and all nations are taking steps to equip their troops with protection against it. Gas proved itself so effective a weapon, it offers such possibilities of surprise, and it can be produced so easily in the peace equip ment of the chemical industry that it would be rash to discount the possibility of its use under the conditions of war psychology. Moreover it is difficult to maintain that it is less humane than other weapons. For example, the total recorded British gas casualties were 180,983 with 6,062 deaths, whilst the mortality amongst other battle casualties was about 25%, and it was striking how small a proportion of the gas casualties who survived suffered any permanent disablement.Most forecasts of future wars assign to gas an important role in its use from aircraft against mobilization and manufacturing centres and even against the civilian population, and under certain conditions there can be little doubt as to its effectiveness. As regards its use in the field, much depends on whether the type of warfare is such as to permit of its employment in sufficient quantity and concentration. Position warfare offers exceptional opportunities for its use, but the tank and the aeroplane, which favour a return to some form of mobile warfare, may themselves become the means by which gas may be discharged most advantageously.

BIBLIOGRAPHY.-A.

A. Fries and C. J. West, Chemical Warfare Bibliography.-A. A. Fries and C. J. West, Chemical Warfare (1921) ; "Diseases of the War," Official History of the Great War: Medical Services, vol ii. (1923) ; Hanslian and Bergendorff, Der chemische Krieg (1925) ; Meyer, Der Gaskampf and die chemischen Kampfstofe (Leipzig, 1925) ; J. B. S. Haldane, Callinicus, a Defence of Chemical Warfare; Capt. B. H. Liddell-Hart, Paris or the Future of War; The Remaking of Modern Armies; Col. J. F. C. Fuller, The Reformation of War. (H. B. HA. ; C. G. Do.) Chemical warfare deals with the direct application of chem icals as weapons. It is concerned with the chemical not as an explosive agent to propel a bullet or fragment of metal, but as the active agent itself to cause casualties by irritation, burning or asphyxiation ; to make ground untenable ; to screen operations or lessen the enemy's fire power by creating a smoke screen; and to damage enemy material or personnel in incendiary effect or otherwise. The adoption of chemicals as weapons was as logical as it was inevitable in the World War in which all the principal combatants were nations highly developed scientifically. When the German advance was halted by the Battle of the Marne, both sides firmly entrenched themselves. A stalemate resulted ; it was found that neither side could advance. The machine gun had increased fire power to such an extent that only by an impossible superiority in man power could ground be captured. Mobility for either the Allies or the Germans had gone. Through the winter of 1914 and 1915, with both sides out of artillery .ammunition, the man in the trench was bound to have a technical superiority over the attacker.Both sides felt the need of a weapon that would search out the defender in his rabbit warren of trenches and holes and rob him of the protection of his sandbags and earthworks. The scientist provided this weapon in chemicals, a weapon continuous in time and space. Thus modern chemical warfare was born. The first definite gas attack against American troops took place on the night of Feb. 25, 1918 near Seicheprey. Approximately 175 pro jectiles containing phosgene and chloro-picrin were fired. The troops on this sector were warned that just such an attack might be expected. In spite of this warning, heavy casualties occurred. From that time on, American troops were subjected to numerous gas attacks, the results of which are best shown by the final re port of the surgeon general, U.S. Army, on casualties. The ques tion of whether or not chemical warfare is humane is very def initely answered by this report, which shows that while 27% of all American casualties were caused by gas, only 2% of these casualties resulted in death. Of the other 73% of battle casual ties, more than 24% resulted in death. Furthermore, the report of the surgeon general shows conclusively that gas does not in crease susceptibility to tuberculosis in after years and that there is seldom any permanent after effect from gassing. It is the opin ion of military men who know the facts that gas is not as inhuman a method as the more familiar methods of warfare and causes less suffering than the bullet, bayonet, high explosive or shrapnel shells.

That gas played an important part in the war is shown by the fact that it accounted for some 800,000 casualties divided ap proximately as follows : Russia, 275,000 ; France, 190,000; Eng land, 181,000; Germany, 78,763; United States, 70,552; Italy, 13,300. Protection against gas started immediately after the first gas attack and has kept pace with the offensive since that time. The first protective devices were pads of cotton dipped in a chem ical solution and tied over the mouth and nose. Then followed helmets saturated with a neutralizing solution worn over the head, thus protecting the eyes as well as the lungs of the wearer. Increase in the use of chemicals during the war caused the devel opment of the type of mask or respirator which consists in an im permeable facepiece to which is attached a filter containing ab sorbent charcoal and neutralizing chemicals.

The American army adopted as their first mask one modelled after the British box respirator. This consisted of a facepiece to protect the eyes and respiratory tracts, a canister which filtered the air breathed and a canvas satchel for carrying. The facepiece of rubberized fabric covered the whole face and was equipped with a rubber mouthpiece and nose clip. A hose tube joined the canister to the facepiece. The air breathed passed through the canister where it was purified, up the tube and through the mouth piece to the lungs of the wearer. Breathing through the nose was prevented by the nose clip. The American gas service recognized the discomfort of the mouthpiece and nose clip, and before the end of the war had developed a respirator which combined the ad vantages of the French Tissot mask which had no mouthpiece or nose clip, and the British box respirator. The present gas mask of the United States army is a further development of the Amer ican Tissot mask. The air is filtered by a highly activated form of coconut shell charcoal and neutralized by granules of • soda lime and permanganate in the canister. It passes through a corru gated hose tube into the facepiece and across the eyepieces, thus keeping these clear. The facepiece is made of moulded rubber cov ered with stockinet for protection and is modelled accurately to fit all types of faces. The whole apparatus is carried in a satchel under the soldier's left arm. Protection of the body against burns from mustard gas is obtained by treating clothing with certain chemicals.

Chemical warfare presented to the Allies not only a new tacti cal and strategic problem but an industrial problem as well. The quantities of chemicals necessary to carry out gas operations on a large scale are measured in hundreds of tons. In the manufac ture of practically all chemical agents, the Germans had the in itiative. The sacrifices in men and money which the Allies had to make before their chemical plants could compete with Ger man production served as a terrible lesson and in the future a State will regard its chemical industry as one of its greatest assets for national defence.

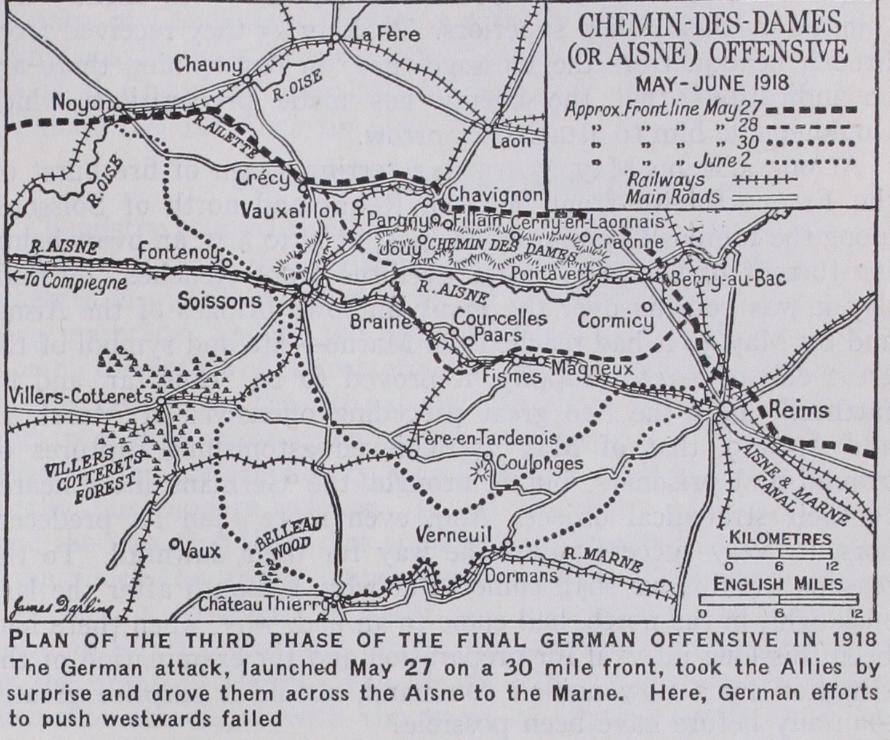

There has been considerable discussion as to the international legal status of chemical warfare. Several treaties have been pro posed to outlaw the use of chemicals in war. In 1922 the United States ratified the Five-Power Treaty at Washington. It sought to make illegal the use in war of poison gas and submarines. This treaty required ratification by all five powers, before it became binding on any one of the contracting parties. As all have not ratified the treaty, it is not in effect. An authoritative letter published in the Congressional Record of Dec. 13, 1926, brings out clearly the point that no proposed treaty, if such treaty should finally become effective, would prevent the United States from doing all work in chemical warfare that it felt necessary to insure itself against surprise or disaster in a war. Most military writers agree that chemical warfare is an effective and humane weapon and that its use on a large scale must be viewed as probable. Although stabilized warfare brought about and presents the great est opportunities for the use of gas, the development of chemical warfare in connection with the aeroplane and the tank must be counted upon to make even more advantageous its employment in mobile warfare. (J. E. Z.; A. A. F.) BATTLE OF THE, 1918. This is the name commonly given to the May offensive of the Germans in 1918, the third act of their plan to reach a military decision before the weight of American numbers could turn the scales against them. It is alternatively called the Battle of the Aisne, 1918, or, less frequently, the Battle of Soissons-Reims. After the relative failure of the German offensives of March and April it was essential for the Germans, if they wished to preserve the initiative, to deliver another powerful blow without delay. The choice of the front of attack and the battle-ground fell on the oft-contested chain of heights between the Ailette and the Aisne, the Chemin-des-Dames.

Dispositions for the German Attack.

The German Su preme Command had decided to attack with the VII. and I. Armies against the sector between north of Soissons and Reims. If this attack proceeded favourably it was to be prolonged on the right over the Ailette to the Oise and on the left as far as Reims. The German Supreme Command hoped that the push southward would succeed in reaching the neighbourhood of Soissons and Fismes, and by this means attract strong forces from Flanders, so that it might be possible to continue the attack there according to plan. Preparations began about the middle of May. The VII. Army under Bohm was charged with the main attack across the Chemin-des-Dames, the I. Army under Below with the neigh bouring attack on the left in the direction of Compiegne. The right wing of the main attack, the LIV. Corps and the VIII. Res. Corps, had the task of pushing forward in a south-westerly direc tion on both sides of Soissons. The XXV. Res. Corps was to strike on both sides of Cerny-en-Laonnais direct towards Braisne, and on the east to take as much country as possible towards the south; the IV. Res. Corps was to attack the high ground at the eastern end of the Chemin-des-Dames, immediately north of Cra onne; in concert with this on the left the LXV. Corps was to occupy with its left wing the river bend north of Berry-au-Bac. Of the I. Army only one corps was to be launched at the outset to throw the opposing forces over the Aisne-Marne canal. The corps was to provide itself with bridgeheads in order to take the heights of Cormicy if the attack of the VII. Army proceeded favourably.For success there were two essentials ; the first, surprise ; and the second, effective artillery preparation. Most elaborate and thorough precautions were taken to secure secrecy. As regards artillery preparation the ascent of the steep slopes on the heights of the Chemin-des-Dames was only possible if the Germans should succeed in silencing the bulk of the opposing guns. All registration was to be abandoned in order to surprise the enemy as much as possible. The first aim was to be a thorough gassing of the Allied position right down into the Aisne valley. Prepara tions were completed by the evening of May 26, 1918. At that moment four battle-worn British divisions were resting in this supposedly quiet sector. They had been sent to the French front, after strenuous exertions in the battles of the Lys, in return for French reinforcements which had gone north to the aid of the Brit ish in the later stages of that "backs to the wall" struggle. On the tranquil Aisne they could recuperate, while still serving a useful purpose as guardians of the trench-line. It was too quiet to be true. But the uneasiness of the local British commanders— shared by certain of their French neighbours—was slightly dis counted by their Allied superiors. On May 25 they received from French headquarters the message that "in our opinion there are no indications that the enemy has made preparations which would enable him to attack to-morrow." At one A.M. on May 27, 1918, a terrific storm of fire burst on the Franco-British front between Reims and north of Soissons, along the famous Chemin-des-Dames; at 4:3o A.M. an overwhelm ing torrent of Germans swept over the front trenches; by mid day it was pouring over the many unblown bridges of the Aisne, and by May 3o it had reached the Marne—site and symbol of the great ebb of 1914. Happily, it proved to be "thus far, and no farther." Like the two great preceding offensives of March 21 and April 9, that of May 27 achieved astonishing captures of ground and prisoners, but it brought the Germans little nearer to their strategical object. And, even more than its predeces sors, its very success paved the way for their downfall. To the reasons for this we shall come. But why, a month after the last onslaught, in the north, had come to an end, why, when there had been this long interval for preparation and for examination of the situation by a now unified command, should a surprise greater than any before have been possible? It has long been known, of course, that the French command, that directly concerned with the safety of this Aisne sector, did not believe in the likelihood of an attack. Nor did the British higher command, which, however, was personally concerned with the front in the north. But the intelligence of another of the Allies, better placed to take a wide survey, did give the warning— only to be disregarded until too late. On May 13, a fortnight after the fighting in Flanders had died away, the British intelli gence came to the conclusion that "an attack on a broad front between Arras and Albert is intended." Next day this was dis cussed at a conference of the intelligence section of the Ameri can Expeditionary Force, and the head of the battle order (of the enemy) section gave a contrary opinion holding that the next attack would be against the Chemin-des-Dames sector, and be tween May 25 and 3o.

The warning in detail was conveyed to the French general headquarters, but fell on deaf ears. Why should credence be given to an opinion coming from such a new army, not yet tested in battle, over the verdict of war-tried and highly-developed in telligence services? The warning was reiterated, however, and the French intelligence was won over to its acceptance. But now, as at Verdun two years before, the operations branch opposed until too late the view of its own intelligence. This time, how ever, it was less blameworthy, for it was tugged the other way by the comforting assurances of the commander of the VI. French Army, in charge of the Chemin-des-Dames sector. This general, indeed, had a still heavier responsibility, for he insisted on the adoption of the long-exploded and wasteful system of massing the infantry of the defence in the forward positions. Besides giving the enemy guns a crowded and helpless target, this method ensured that, once the German guns had eaten up this luckless cannon f odder, the German infantry would find practically no local re serves to oppose their progress through the rear zones. In similar manner all the headquarters, communication centres, ammunition depots and railheads were pushed close up, ready to be dislocated promptly by the enemy bombardment.

Petain's instructions on a deep and elastic system of defence had evidently made no impression on this Army command, so that it was still less a matter for wonder that the protests of junior British commanders met with a rebuff. It was unfortunate, also if perhaps less avoidable, that when the four British divisions form ing the IX. Corps (Hamilton Gordon) arrived from the north at the end of April, their depleted ranks filled up with raw drafts from home, they were hurried straight into the line, as the best place to complete their training. The backbone of the Aisne de fences was formed by the historic Chemin-des-Dames ridge north of the river. The eastern half of this "hog's back" was to be held by the British, with the 5oth Division (Jackson) on the left, next the 8th Division (Heneker), and, beyond the end of the ridge, in the low ground from Berry-au-Bac along the Aisne and Marne canal, the 21st Division (Campbell), joining up with the French troops covering Reims. The infantry of the 25th Division (Bain bridge) was in reserve.

Altogether the French VI. Army front was held by four French and three British divisions, with three and one respectively in reserve. Against these tired or raw troops, in the main attack from Berry-au-Bac westwards, fifteen German divisions, all but one brought up fresh, were to fall upon five, with two more for the subsidiary attack between Berry-au-Bac and Reims, while seven German divisions lay close up in support. Even so, the German superiority was not so pronounced as in the March and April offensives, whereas both the rapidity and the extent of their progress were greater. Yet this time the tactical surprise of the assault was unaided by the heavy ground mists which had pre viously helped so much by wrapping their initial advance in a cloak of invisibility. The conclusion is, therefore, that the ad vantage was due in part to the strategic surprise—the greater unexpectedness of the time and place—and in part to the folly of exposing the defenders so completely to the demoralizing and paralyzing effect of the German bombardment—by 3,719 guns on a front of under 4o miles. This last, indeed, was a form of surprise, for the object of all surprise is the dislocation of the enemy's morale and mind, and the effect is the same whether the enemy be caught napping by deception or allows himself to be trapped with his eyes open.

We pass to the events of May 27. For three and a half hours the unfortunate troops had to endure a bombardment of excep tional intensity. And the ordeal of those hours of helpless en durance, amid the ever swelling litter of shattered dead and un tended wounded, was made more trying by crouching, semi suffocated in gas-masks. Then the grey waves advanced—relief, if only of action, at last. Three-quarters of an hour later they had reached the crest of the ridge in the centre near Ailles. This uncovered the flank of the left British division, the 5oth, forcing its survivors to fall back down the other slope. Next to it, the 8th Division was being forced to give way, although two of its bri gades held on stubbornly for a time on the north bank of the Aisne. On the British right, the attack on the 21st Division de veloped later; this division was awkwardly placed with the swampy Aisne and Marne canal running through the centre of its battle zone, but most of it was successfully extricated and with drawn west of the canal. By midday the situation was that the Germans had reached and crossed the Aisne at most points from Berry-au-Bac to Vailly—helped by the fact that the order to blow up the bridges had been given belatedly. Hitherto the German progress had been evenly distributed, but in the afternoon a heavy sagging occurred in the centre, at the junction of the French and British wings, and the Germans pushed through as far as Fismes on the Vesle. This was natural, both because the joint is always the weakest point, and because the heaviest weight—more than 4 to 1—of the assault had fallen on the two French divisions in the centre and the left of the loth Division adjoining them.

This sagging, together with the renewed German pressure, com pelled a drawing back of the flanks. On the east, or British flank, this operation was distinguished by a remarkable manoeuvre of the 21st Division, wheeling back during the night through hilly, wooded country, while pivoting on and keeping touch with the Algerian division, which formed the right of the Army. After a pause in the morning of May 28, the Germans forced the passage of the Vesle, and on the 29th they made a vast bound, reaching Feee-en-Tardenois in the centre, and capturing Soissons on the west, both important nodal points, which yielded them quantities of material. The German troops had even outstripped in their swift onrush the objectives assigned to them, and this, despite the counter-attacks which Pratain was now shrewdly directing against their sensitive right flank. On the 3oth the German flood swept on the Marne, but it was now flowing in a narrowing central chan nel, for this day little ground was yielded by the Allied right flank, where the 19th Division as well as French divisions had come to reinforce the remnant of the original four British divisions, which next day were relieved.

From May 31 onwards the Germans, checked on the side of Reims and in front by the Marne, turned their efforts to a west ward expansion of the great bulge—down the corridor between the Ourcq and the Marne towards Paris. Hitherto the French re serves had been thrown into the battle as they arrived, in an at tempt to stem the flood, which usually resulted in their being caught up and carried back by it. On June i, however, Petain issued orders for the further reserves coming up to form, instead, a ring in rear, digging themselves in and thus having ready before the German flood reached them a vast semi-circular dam which would stop and confine its now slackening flow. When it beat against this in the first days of June its momentum was too dimin ished to make much impression, whereas the appearance and fierce counter-attack of the and American Division at the vital joint of Chateau-Thierry was not only a material cement, but an inesti mable moral tonic to their weary allies. In those few days of "flooding" the Germans had taken some 65,000 prisoners, but whereas this human loss was soon to be more than made up by American reinforcements, strategically the Germans' success had merely placed themselves in a huge sack which was to prove their undoing less than two months later (see MARNE, SECOND BATTLE OF THE). As in each of the two previous offensives, the tactical success of the Germans on May 27 proved a strategical reverse, because the extent to which they surprised their enemy surprised and so dislocated the balance of their own command.

As the disclosures of Gen. Kuhl have revealed, the offensive of May 27 was intended merely as a diversion, to attract the Allied reserves thither preparatory to a final and decisive blow at the British front covering Hazebrouck. But its astonishing opening success tempted the German command to carry it too far and too long, the attraction of success drawing thither their own reserves as well as the enemy's. Nevertheless it is a just speculation as to what might have resulted if the attack had begun on April 17, as ordered, instead of being delayed until May 27, before the prep arations were complete. The Germans would have worn out fewer of their reserves in ineffectual prolongations of the Somme and Lys offensives, while the Allies would have still been waiting for the stiffening, moral and physical, of America's man-power. Time and surprise are the two supreme factors in war. The Germans lost the first and forfeited the second by allowing their surprise to surprise themselves. (B. H. L. H.)