Chest

CHEST, a large box of wood or metal with a hinged lid. The term is used for many different kinds of receptacles ; and in anatomy is transferred to the portion of the body covered by the ribs and breastbone (see RESPIRATORY SYSTEM). Chests as articles of furniture are of the greatest antiquity. The chest was the com mon receptacle for clothes and valuables, and was the direct an cestor of the "chest of drawers," which was formed by enlarging the chest and cutting up the front. It was also frequently used as a seat. Indeed, in its origin it took in great measure the place of the chair, which, although familiar enough to the ancients, was a luxury in the days when the chest was already an almost uni versal possession. In the early middle ages the rich possessed them in profusion, used them as portmanteaux, and carried them about from castle to castle. These portable receptacles were often covered with leather and emblazoned with heraldic designs. As houses gradually became more amply furnished, chests and beds and other movables were allowed to remain stationary; and the chest finally took the shape in which we best know it—that of an oblong box standing upon raised feet. As a rule it was made of oak, but sometimes of chestnut or other hard wood.

Types.

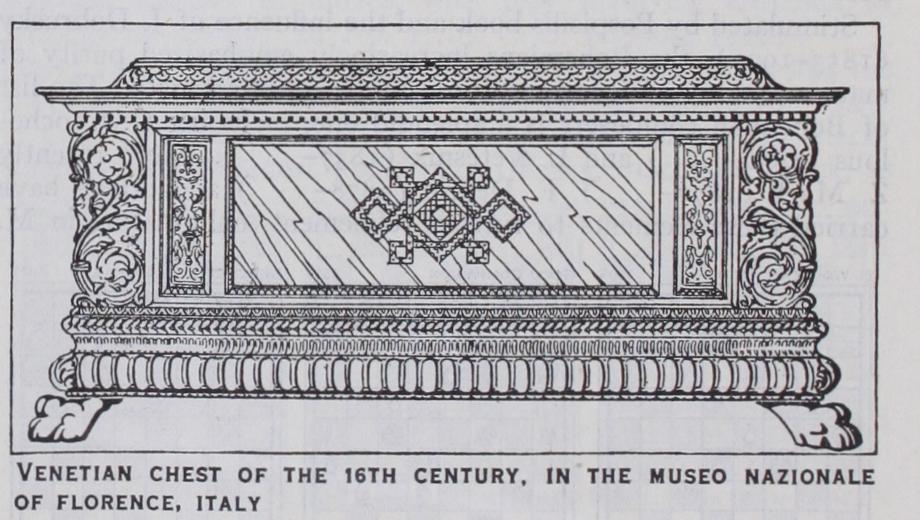

There are, properly speaking, three types of chest— the domestic, the ecclesiastical and the strong box or coffer. Old domestic chests still exist in great number and some variety, but the proportion of those earlier than the latter part of the Tudor period is very small; most of them are Jacobean in date. Very frequently they were made to contain the store of house linen which a bride took to her husband upon her marriage. In the 17th century Boulle and his imitators glorified the marriage coffer until it became a gorgeous casket, almost indeed a sarcoph agus, inlaid with ivory and ebony and precious woods, and en riched with ormolu, supported upon a stand of equal magnificence. The Italian marriage-chests (cassone, q.v.) were also of a rich ness which was never attempted in England. The main character istics of English domestic chests (which not infrequently are carved with names and dates) are panelled fronts and ends, the feet being formed from prolongations of the "stiles" or side posts. A certain number of 17th-century chests, however, have separate feet, either circular or shaped after the indications of a some what later style.There is usually a strong architectural feeling about the chest, the front being divided into panels, which are plain in the more ordinary examples, and richly carved in the choicer ones.

The plinth and frieze are often of well-defined guilloche work, or are carved with arabesques or conventionalized flowers. Archi tectural detail, especially the de tail of wainscoting, has indeed been followed with considerable fidelity, many of the earlier chests being carved in the linenfold pattern, while the Jacobean examples are often mere reproductions of the pilastered and recessed oaken mantlepieces of the period.

Occasionally a chest is seen which is inlaid with coloured woods, or with geometrical parquetry. Perhaps the most elaborate type of English parquetry chest is that named after the vanished Palace of Nonesuch. Such pieces are, however, rarely met with. The entire front of this type is covered with a representation of the palace in coloured woods. Another class of chest is incised, sometimes rather roughly, but often with considerable geometrical skill.

The more ordinary variety has been of great value to the forger of antique furniture, who has used its carved panels for con version into cupboards and other pieces, the history of which is not easily unravelled by the amateur who collects old oak. Towards the end of the 17th century chests were often made of walnut, or even of exotic woods such as cedar and cypress, and were sometimes clamped with large and ornamental brass bands and hinges. The chests of the 18th century were much larger than those of the preceding period, and as often as not were furnished with two drawers at the bottom—an arrangement but rarely seen in those of the 17th century—while they were often fitted with a small internal box fixed across one end for ready access to small articles. The chest was not infrequently unpanelled and unorna mented, and in the latter period of its history this became the ruling type.

Ecclesiastical Chests.

These appear to have been used al most entirely as receptacles for vestments and church plate, and those which survive are still often employed for the preservation of parish documents. A considerable variety of these interesting and often exceedingly elaborate chests are still left in English churches. They are usually of considerable size, and of a length disproportionate to their depth. This no doubt was to facilitate the storage of vestments. Most of them are of great antiquity. Many go back to the i4th century, and here and there they are even earlier, as in the case of the coffer in Stoke d'Abernon church, Surrey, which is unquestionably 13th-century work. One of the most remarkable of these early examples is in Newport church, Essex. It is one of the extremely rare painted coffers of the 13th century, the front carved with an upper row of shields, from which the heraldic painting has disappeared, and a lower row of roundels. Between is a belt of open tracery, probably of pewter, and the inside of the lid is dec orated with oil paintings repre senting the Crucifixion, the Virgin Mary, St. Peter, St. John and St. Paul. The well-known "jewel chest" in St. Mary's, Oxford, is one of the earliest examples of i4th century work. Many of these ecclesiastical chests are carved with architectural motives —traceried windows most fre quently, but occasionally with the linenf old pattern. There is a whole class of chests known as "tilting coffers," carved with rep resentations of tournaments or feats of arms, and sometimes with a grotesque admixture of chivalric figures and mythical monsters. Only five or six exam ples of this type are known still to exist in England, and two of them are now in the Victoria and Albert museum, London. It is not certain that even these few are of English origin—indeed, very many of the chests and coffers of the 16th and 17th centuries are of foreign make. They were imported into England chiefly from Flanders, and were subsequently carved by native artisans, as was the case with other common pieces of furniture of those periods. The huche or "hutch" was a rough type of household chest.Coffer is the word properly applied to a chest which was in tended for the safe keeping of valuables. As a rule the coffer is much more massive in construction than the domestic chest it is clamped by iron bands, sometimes contains secret receptacles opening with a concealed spring, and is often furnished with an elaborate and complex lock, which occupies the whole of the underside of the lid. Pieces of this type are sometimes described as Spanish chests, from the belief that they were taken from ships belonging to the Armada. However, these strong boxes are frequently of English origin, although the mechanism of the locks may have been due to the subtle skill of foreign lock smiths. A typical example of the treasure chest is that which belonged to Sir Thomas Bodley, and is preserved in the Bodleian library at Oxford. The locks of this description of chest are of steel, and are sometimes richly damascened.

Another kind of chest in use in earlier days was that signified in the expression a "chest of viols." This took the form of a sol idly-constructed, baize-lined press or cupboard, designed to ac commodate stringed musical instruments—in the case of a "chest of viols," six viols of varying sizes.