Child Psychology

CHILD PSYCHOLOGY. General psychology is concerned chiefly with the mental life of human beings. Child psychology considers the complicated course of mental development which precedes maturity, and embraces newborn infancy as well as childhood and youth. Adolescence, the complex period of transi tion which begins with puberty in the early teens and extends into the middle twenties, presents important psychological problems relating to the attainment of maturity, but the term, child psychol ogy, is ordinarily restricted largely to the pre-adolescent period.

The Problems of Child Psychology.—The central scientific problem of child psychology is the delineation and interpretation of the growth of the mind, or, in other words, of the ontogenesis of human behaviour. It is impossible to describe the child mind as though it were a fixed entity, for the gamut of growth is too wide. From the mewling infant to the whining schoolboy, "with satchel and shining morning face," the mental life of the child is changing constantly. Psychologically, it is necessary to reckon even with the behaviour differences between the four-months and the six-months old infant. Function in relation to age, the nature of individual differences in children of precisely the same age, the relations between age and maturity, are basic problems in a sys tematic psychology of child development.

Methods of Investigation.—The growth of the mind can be traced only by observation of the child's characteristic behaviour. There is no possibility of observing his consciousness in any im mediate way, and there is meagre possibility of enlisting the child's introspection. It remains, therefore, to note scientifically the growth of behaviour itself by any or all of the following methods: (a) Naturalistic observation takes account of the child as he is in his ordinary surroundings. It reports episodes and phases of his life ; or it records in a biographical manner, as in Shinn's classical notes. (b) Experimental observation limits and controls its data by devices and instrumental technique. (c) Psycho-metric and normative studies aim to define behaviour in quantitative and orientational terms so that children of varying ages, capacities and conditions may be compared through standardized tests and statistically derived norms. (d) Clinical investigation combines two or more of the above methods, and focuses intensively on selected individuals, correlating data from a variety of angles. Psycho-analysis is a special type of clinical method, which serves in some instances to reveal the psycho-genetic importance of in fantile behaviour events in determining deviations in adult con duct. (e) Co-operative child research, in recent years, has de veloped so extensively as to deserve special mention. It is exemplified in university research centres like those at Iowa, Chi cago, Minnesota, California, Yale, Berlin, Vienna and Geneva, where investigations in genetic psychology, biometrics, anthropo metry and pediatrics, as well as clinical, educational and child guid ance activities, are co-ordinated. There is an increasing tendency to widen the scope of child psychology so as to include all the phases of child development, and to incorporate the outlook of the medi cal and biological sciences, including biochemistry, developmental physiology and animal psychology. In this sense the study of child development becomes a subdivision of the science of psycho biology.

The Beginnings of Child Behaviour.—From the standpoint of developmental psychology, the whole life cycle is a continuum, and the growth of the mind begins with the growth of individual behaviour. Minkowski, and others, have found evidences of such behaviour throughout most of the prenatal period. Two months after conception, rudimentary body reflexes appear ; the elements of the spinal reflex arc are already found in the foetus of that age. In the third month, mouth movements are evident. In the fourth, fifth and sixth months, deep cervical reflexes and labyrinth reflexes, involving head, arms and legs occur. By the seventh month most of the vital reflexes necessary for extra-uterine exist ence are well advanced, so that the prematurely born child has a chance of survival. There is good reason to believe that the infant of six to nine months, whether within or without the womb, is already a habit-forming creature, able to learn through processes of conditioning. Prematurity of birth does not, however, hasten the general course of the infant's behaviour growth.

Sensori-motor Development.—Sensitivity to light, sound, pressure and temperature, to change of position and internal bodily conditions is present to some degree before birth. The earliest sensory responses are on a spinal and sub-cortical level, whereas well-defined sense-perceptions, with appreciation of form, space and localization, depend upon the maturation of the whole sensory apparatus, particularly the cortex, and upon the organization of habits of response through conditioning. Hearing undergoes rapid organization in the first two months, but the acquisition of visual and oculo-motor control is a long process in which horizontally moving objects are followed before vertically moving objects. There is selective regard for the human face by the fourth week. A small quarter-inch pellet is regarded as early as 20 to 24 weeks. The early sensory life of the child is probably not a "big blooming, buzzing confusion" ; but the stimuli are more or less distinctly sensed as arising out of a neutral or contrasting background (Gestalt).

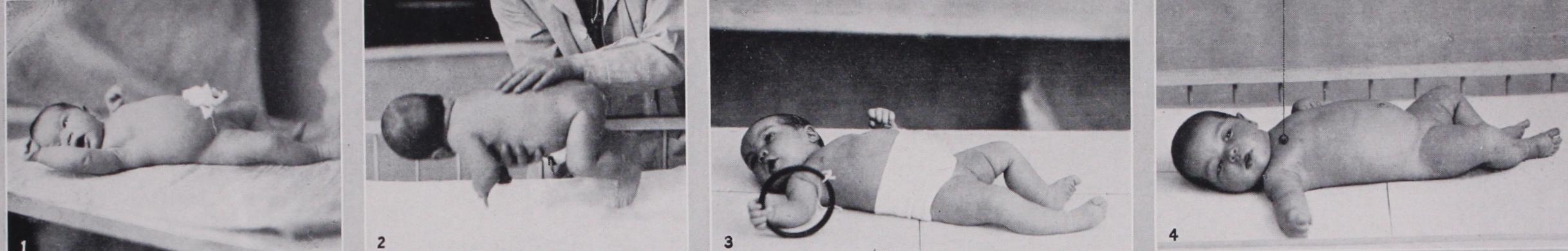

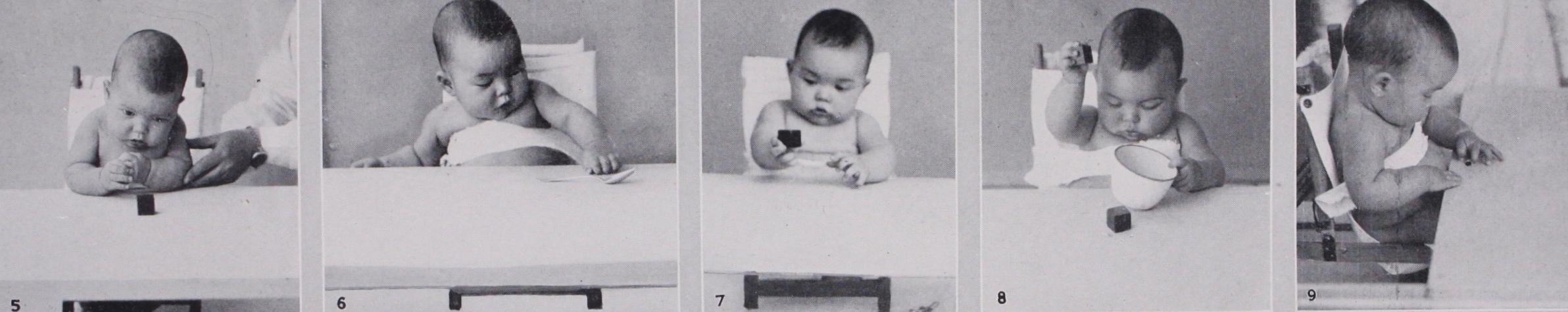

Although there are individual variations, sensori-motor develop ment tends to follow orderly sequences suggested by the approxi mate dates which are assigned to the following items : Closing in with two hands upon a dangling object (18 weeks) ; picking up an object on contact (2o weeks) ; reaching for object on sight (24 weeks) ; plucking pellet with pincer prehension (4o weeks) ; right or left handedness partially established (4o weeks) ; sitting alone (9 months) ; walking alone (I 5 months) ; running (2 years) ; scribbling imitatively (I year) ; scribbling spontaneously (II years) ; copying a circle (3 years), a square (5 years), a diamond (7 years). The rate of tapping (with a stylus or pencil) steadily rises from about zoo per minute at 4 years to about 25o at 12 years.

Language.—Language constitutes perhaps the most compli cated of all the mental achievements of childhood. The infant begins his post-natal career with a cry, which in the first few weeks becomes differentiated for hunger, cold, discomfort. At three months, pleasure is vocalized. At four months, laughter occurs. At five months eagerness is voiced; sound play, at first solitary, later imitative and socialized, becomes increasingly channelized. Interjections and syllables like "dada" and "mama" become well defined at nine months. Heedful responsiveness to words, and adjustment to simple verbal commands or signals, follow soon after. At one year the child may have a vocabulary of three words; at two years it is nearer Soo; at six years it is nearly 3,000 ; at twelve years it may be reckoned (Stanford-Binet scale) at over 14,00o. There are large individual differences which become enor mous when retarded and precocious children are compared. About 6o% of two-year old children use sentences from two to eight words in length. Verbs are relatively much more frequent in the young child than the adult. Conjunctions show a slow and steady increase from two to eight years, and subordinate clauses appear before the fourth year. Piaget has shown that during the first seven years the child's speech is highly ego-centric, even his con versation having a monologue aspect. At about eight years true communication of thought becomes more characteristic and in fantile notions of causality give way to more conceptual types of judgment and reasoning. Childish lying due to immaturity of the language function also tends to disappear.

Intelligence.—In a psycho-genetic sense the growth of intel ligence begins early. Even the new-born child is a habit-forming creature. Conjointly through experience and maturation of his abilities, he "learns" to adapt himself to his surroundings. He learns to act to cues, sights, sounds, and to relations between things. This adaptability is the essence of that which is later called intelligence. Even before his first birthday he shows insight and can use a string as a tool to pull an attached object toward him; at two years he distinguishes between in and under; at three years he builds from a model a bridge of three blocks ; at five years he defines words in terms of use; at seven years he makes a verbal distinction between a stone and an egg; and at twelve years he can define abstract words such as envy and pity. His memory span, as measured by the number of digits he can recall, increases steadily during these years. He gradually acquires notions of similarity, analogy, truth, error, causation, but his intellectual interests are rooted in the concrete rather than the abstract. Much of his concealed thinking is more naïve and primitive than we suspect.

While the doctrine of psychological recapitulation in an extreme form is to be discredited, it has some applicability to the child's intellectual development. The child tends to follow primitive modes of thought in the early stages of his logic, and does not think merely like an undeveloped adult. Jaensch and others have demonstrated that many children have the gift of eidetic imagery, which is a capacity to reproduce vividly an object once seen and not as a transient pallid image. This natural and valuable child like mental trait is in danger of disappearing under the influence of rationalistic culture.

Personality.—Mental growth results in a steady intensification of individuality. The new-born infant seems relatively inchoate, vegetative and unorganized; but the process of integration begins promptly and issues in a changing complex of attitudes, predis positions and habits, which constitutes his personality. The struc ture of this personality is the result of both intrinsic and extrinsic factors, the intrinsic ones being the organic cravings and propensi ties such as hunger, thirst, fear, rage and aggression, affection, imi tative activity, playful, exploitive and experimental activity. Out of such general tendencies arise all sorts of emotional or instinc tive seeking and avoiding responses, such as curiosity, modesty, self-display, jealousy, emulation and co-operation. Temperamental qualities, constitutional type, and endocrine characteristics, must be counted among the intrinsic factors. The actual patterns of behaviour, however, are decisively shaped by extrinsic condition ing factors through social impress, and by the action of the con ditioned reflex. Psycho-analysis places stress on nutritional, sexual and presexual factors as moulding both the conscious and uncon scious trends of conduct.

From the standpoint of personality, the development of the child's mind consists in the progressive attainment of emotional independence, or morale. This is a process of increasing detach ment from the parental care upon which the infant is so completely dependent ; hence the parent-child relationship is a key to the progress of the psychological maturity of the child. The child's mind is not a faded replica of the adult mind, but has unique characteristics which are inadequately understood. Schiller com bined truth and imagination when he remarked that the adult would be a genius if he but lived up to the promise of childhood. Sincerity, directness, originality, naïve freedom from inhibition, vitality and happiness are characteristic of childhood at its best, and the mental health of the race depends upon an increasing pro jection of these qualities into maturity.