Chile

CHILE (possibly from the Quichua Tchili, snow) is a South American, west coast republic, occupying the limited western slopes of the continent south of Peru. It is a narrow ribbon-like country, varying from 46 to 25o m. wide, with a meridional length of 2,661 m., and extending approximately between 17° 25' S. and 59' S. It thus has a greater inhabited latitudinal range than any other country in the world. No thorough survey of the entire country has ever been made, but the area is estimated officially at Q51,515 Km' (290,085 sq.m.). The country is bounded on the north by Peru, on the east by Bolivia and Argentina, and on the south and west by the Pacific ocean. Topographically, the country is divided into three fairly distinct belts : the Andean on the east, the coast range on the west, and the central or longitudinal valley in the middle. Climatically it is also divided into three zones: the desert region, north of about 30°, where rain rarely falls; the southern rainy belt, south of about 40°, with a precipitation of in. or more, and in places more than twice that amount; and the central zone, between the two in latitude and with a much more favourable rainfall. The country may also be divided geo graphically into three divisions, roughly corresponding to the climatic zones : the northern mineralized region with its life centered about mining; the central, made up of the justly famed Vale of Chile, the agricultural centre with its allied industries; and the southern forested part, sparsely populated, with most of the land given over to the Indian.

Physical Features.

The northern coast of Chile conveys the impression of a great land barrier, with a remarkably even sky line, that rises almost vertically out of the sea to a height of 600 to 1,50o feet and rarely up to 6,000 feet. There is no true coastal plain and only at the more sheltered places or where a stream cuts through to the ocean is there sufficient level land for town sites. This coastal bluff materially lengthens the routes into the interior and thus seriously handicaps movement. South of Val paraiso the coastal escarpment is more broken and the elevations assume the characteristics of a mountain chain. From Chiloe south the region subsides leaving only the higher parts of the coastal range above the water as islands. The coast range therefore is not continuous but is an elevated plateau area, presenting a steep escarpment toward the west and gradual slopes to the eastward.The great barrier ranges of the Andes, which make up fully a third of the country, may be divided roughly into two groups at about 30° south. The southern forms a rather narrow complex chain composed of two parallel ranges of fairly equal altitude and so close together as to permit little development of intermediate valleys and plateaus. In general the chain increases in width toward the north until it reaches a maximum of 10o m. or more. It also increases in height from an altitude of 6,000 to 7,000 ft. at the southern end, until it culminates at about 32° 30' S. in Aconcagua, which is over 23,000 f t. above sea level. This section of the Andes is a less serious barrier than others because the mountain belt is relatively narrow and the passes comparatively low. The highest part of the tunnel on the trans-continental railway from Valparaiso to Buenos Aires is 10,469 ft., and of the nearby Uspallata pass, 12,795 feet. Southward occur still lower passes until at about 40° 30' S. the Nahuel Huapi is only 4,920 feet. From this point onward the passes are low enough to permit trade to alternate between Chilean and Argentine centres. This entire southern section offers little to man and consequently is very sparsely settled. The lack of water in the north makes the working of mines difficult, while the cold and excessive precipita tion of the south, coupled with the general ruggedness of the section, renders much of the south unfavourable even to grazing. Yet from Aconcagua to the strait snow domes and glaciers give unexcelled dignity and beauty to the range.

North of 30° the Andes are divided into several chains of which the western forms the major eastern boundary of northern Chile. No important stream cuts this western range, which is higher than the others and has higher passes. Two railways cross it, the one from Arica at 13,956 ft. and the one from Antofagasta at 12,972 feet. The former utilizes 22 m. of cog-rails in its entire length of 281 miles. The extreme ruggedness, the aridity, and the cold of this section limit crop raising and grazing, but it is highly mineralized, although handicapped by the lack of water.

Between the coast range and the Andes lies the so-called longi tudinal valley. This is not a true valley but an irregular depres sion, in places 25 to 5o m. wide and at times reaching an altitude of 3,00o to 4,00o feet. In some sections it is broken by isolated groups of mountains or by spurs from the main range, which divide the portion above 30° S. into a series of basins, locally known as pampas. The most northern of these is the Tamarugal extending north from the river Loa. This differs from the others in that the ground Nater in places lies within four or five feet of the surface. Although on the whole this pampa is very barren of vegetation there are remnants of what once must have been ex tensive thornwood areas. The desert of Tarapaca lies in the western part of the Tamarugal pampa and furnishes nearly half of Chile's nitrate. Practically all the rest of the nitrate is produced in the neighbouring province of Antofagasta although a very small amount comes from Atacama still farther south. In this province the desert pampas end with an irregular mass of low mountains which occupy the whole belt between the ranges, until approxi mately the latitude of Valparaiso. Here begins the Vale of Chile, one of the finest agricultural valleys in the world, which is con tinued south until approximately 40°. The longitudinal valley then gives away to a series of lakes, and then to a complex series of beautiful islands sparsely inhabited by Indians. (W. H. Hs.) Geology.—Along the coast of Chile lies a belt of rocks formed mainly of old granite and schist and overlying Cretaceous and Tertiary deposits; farther inland is the Western Cordillera of the Andes, which is composed chiefly of intrusive masses, volcanic rocks and folded Mesozoic beds. The deposit in the great longi tudinal valley of Chile, which lies between these two zones, is formed of debris that is in places more than 30o ft. thick. In northern Chile the rocks of the coastal zone, which disappear northward beneath the Pacific, consist mainly of isolated masses that stand close to the shore or that project into the sea. South of Antofagasta these old rocks, which there begin to rise to higher levels, form a nearly continuous belt along the coast, extending southward to Cape Horn and occupying the greater part of the islands of southern Chile. They are greatly folded and are doubt less Palaeozoic. In northern Chile the Cretaceous and Tertiary beds of the coastal zone are of small extent, but in southern Chile the Mesozoic beds, which are at least in part Cretaceous, form a rather wide band. The Tertiary coastal beds include both marine and terrestrial deposits, and most of them appear to be of Miocene or Pliocene age. The whole of the northern part of Tierra del Fuego consists of plateaus formed of horizontal Tertiary beds. The northern part of the Chilean Andes, which is the Western Cordillera of Bolivia, consists almost entirely of Jurassic and Cretaceous sediments and Tertiary eruptive rocks. The Mesozoic beds are thrown into a series of parallel folds, which run in the direction of the mountain chain. Into these folded beds are intruded granitic and other igneous rocks of Tertiary age, and upon this foundation rise the cones of Tertiary and later vol canoes. Triassic rocks are found only at La Ternana, near Copiapo, where coal seams containing upper Triassic (Rhaetic) plants have been found, but the entire Mesozoic series appear to be repre sented at different places. The Mesozoic rocks are chiefly marine sandstone and limestone, but they include also tuff and con glomerate of porphyry and porphyrite. These porphyritic rocks, which form a characteristic element of the Southern Andes, are volcanic, and as they contain marine fossils they must have been laid down beneath the sea. They are not confined to any one geologic horizon but occur at different levels in the Jurassic beds and at some places in the Cretaceous. Here and there they may be traced laterally into the more normal marine deposits of the same age. A large part of the Andes is covered by the products of the great volcanoes that still form the highest summits. The volcanic rocks are liparite, dacite, hornblende andesite and pyroxene andesite. The recent lavas of the volcanoes in southern Chile are olivine-bearing hypersthene andesite and basalt.

(G. McL. Wo.) Ports.—As outlets for her products Chile is unusually rich in ports, but singularly unfortunate in harbours. These, for the most part, are little more than open roadsteads, and the transfer of goods in practically all cases is done by means of lighters. Moreover the heavy swells along the major part of the coast fre quently cause the transfer of goods to be abandoned temporarily for hours, or even days. Of the 57 ports listed relatively few are very important in international trade, and due to the abrupt slope of the ocean bottom artificial protection is both costly and difficult. Many breakwaters have been constructed of recent years, how ever, particularly at Antofagasta and Valparaiso, but without securing thoroughly safe anchorage at those ports. Valparaiso also illustrates the case of an older port which is favoured by the government in its fight for continued supremacy. In colonial times it was selected as the outlet for central Chile because the traffic of that day could pass from the capital to the coast with out encountering any considerable ford. Better natural harbours are to be found in the vicinity, both to the north and south of it and Valparaiso today is meeting serious competition from San Antonio, 5o m. below, which ships the large copper output from the Rancagua district and is gaining in general commerce. Val paraiso is also handicapped by the unwise selection of the route for the railroad leading to the interior. Antofagasta, which of late has surpassed Iquique as the chief port for the shipment of nitrates, I now finds itself contending with Tocopilla to retain the exports and imports passing through it to and from the copper centre at Chuquicamata. Arica, the northernmost port, gains its economic importance as an outlet of the Bolivian plateau but plays a more conspicuous part as a prospective diplomatic pawn. This port and its fellows in the north, like Valparaiso, are hampered by rail way conditions. Talcahuano in the south is the chief naval station of the country as well as the commercial outlet of an extensive section. Near by, Coronel is one of the three ports serving the coal producing district as Cruz Grande, north of Valparaiso with its direct docking facilities, serves the iron mines of Tofo. Valdivia, through its port, Corral, and Constitucion are able to make some commercial use of the rivers on which they are located. Magal lanes (Punta Arenas) on the Straits of Magellan gives Chile the distinction of having the most southerly port in the world.

(W. H. Hs. ; I. J. C.) Rivers.—Due to the general outline and topography of the country, the rivers are short and unimportant except for the life giving waters they may bring, and have little or no significance in directing the settlement or trade of the country. In the north they are few, and for a distance of approximately 60o m., the waters of only one, the Loa, reach the sea throughout the year. This stream, the longest in Chile (44o km.), has made possible certain settlements. The Copiapo, 30o km. long, marking approx imately the southern limit of the northern desert, once discharged its waters into the sea, but rarely does so now, as the needs for irrigation are greater than the supply. The rivers to the south are better fed at their heads and flow through much less arid regions. Some of them become raging torrents at certain times of the year; a few have recently been harnessed for the production of elec tricity. The electrification of the road in the Chilean section of the Trans-Continental has already been completed together with the main line to the capital and other minor developments. With the increased demand for electric current has come also the storage of waters for irrigation.

Lakes.

The lakes of Chile have little significance in the life of the people. In the north occur occasional salt playas, which are dry the greater part of the year. In central Chile, south of the Bio-Bio river, there is a series of very picturesque lakes in the provinces of Cautin and Llanquihue. The largest of these lakes are Ranco and Llanquihue, the former with an estimated area of 200 sq.m. the latter 30o square miles. Due to its natural beauty, the lake region gives promise of becoming the resort place for Chileans during the dry season.

Climate.

Not many countries have the climatic extremes of Chile. The north is an absolute desert, but there is a gradual increase in precipitation through central Chile until it reaches a rainfall in south Chile not surpassed by any extra-tropical region. The strong permanent high pressure area formed over the Pacific at about 30° dominates the climatic conditions of northern Chile, accounting for its northward flowing winds and consequently for the great aridity of the region. South of this high pressure area are the prevailing westerlies or better, northwesterlies, which cor respond to the southwesterlies of the northern hemisphere, but are much stronger. In this belt are the terrific winds that sweep the mountain passes between Chile and Argentina. This belt, migrat ing with the seasons, may occasionally make its influence felt as far north as the region of Coquimbo, where it produces winter rains. At Santiago, this migration is shown in a winter rainfall (3.4 in. in July, o in. in January, annual 14.4 in.). In certain years or series of years this migration does not take place or goes on beyond the normal and the result is either great droughts or heavy rains. South of the southern tip of Chile is a belt made up of numerous low pressure areas, with unusually high barometric gradients, which produce very strong winds averaging over 3o m. per hour, and reaching velocities three or even four times as high. These moving low pressure areas give a constant succession of storms for which the passage around the Horn has been renowned ever since its discovery, and farther northward give the lower part of Chile its westerly winds and immense rainfall.North Chile is quite the driest region of which there is any record. During a 21-year period Iquique had an average rainfall of 1.5 mm. (o.6 inches) and Arica for a 19-year period had less than one-half as much. These averages do not represent normal conditions but show that North Chile is not entirely rainless. On the Andean slopes of this region, periodic summer rains fall as low as 8,000 ft. with occasional heavy snows. These may produce stream floods, which spread mud and gravel over the valley and give rise to temporary salt lakes. Needless to say such rains are calamitous; nitrates are destroyed, the work of the saliteras paralyzed, and the homes of the people, because of the poor mud roofs, practically ruined. This absolute desert condition does not change until in the latitude (27°) of Caldera or Copiapo, where a mean rainfall of about 15 mm. prevails. The rainfall increases rapidly to the south, being 141 mm. (5.6 inches) at La Serena (30°); 500 mm. at Valparaiso (33°). The increase southward is still fairly regular reaching 2,707 mm. (107 inches) at Valdivia so'). From here south, the rainfall is more or less uniform except for local modifications with the striking maximum of 5,379 mm. (216 inches) for south Chile at Balua Felix (53°).

The Chilean rains definitely come from the west. The western Andean slopes are wetter than the valley areas in all latitudes, and this is very noticeable even on the Andean slope of the northern desert region, where a rainfall map, however, shows all of Chile north of 31° with less than io inches. This dry area thrusts a finger down the central valley nearly as far south as Santiago. The 1 o to 20 in. rainfall area, whose southern coastal limit is at Valparaiso, sends a strong arm down the valley nearly as far as Concepcion, with a rain belt on either side of 20-40 in. and with a belt along the western slope of the Andes, overlooking the beautiful agricultural valley, of 4o to 8o inches. This belted arrangement is still more marked in the southern rainy section. The various islands and embayments show a rainfall of 8o-200 in., the mountainous area directly to the east has a precipitation of over Zoo in., while over in Argentina the rainfall gradually de creases again to less than 20 inches.

Irrigation is needed throughout the central valley, not only because of the low rainfall but more especially because the greater part occurs in the winter. This discrepancy becomes less marked from north to south. At La Serena over 98% of the rain comes in the six winter months and 82% in the three colder months. The percentages at Santiago for the same periods are respectively 90 and 73; for Concepcion 83 and 61. Even at Magallanes 61% of the precipitation is during the six winter months. This sea sonal distribution has given Chile an irrigated agriculture with an intensive rather than an extensive use of the land and with the climatic life of the Mediterranean.

In general, for its latitude, the temperature is low. The cold Humboldt Current, which strikes Chile at about 40° S., sends a branch northward along the entire coast, and keeps the tempera tures down and very uniform. The average summer temperature, even at Arica, does not rise above 75° F. Similarly the mean at Iquique is only 66° F, and at Antofagasta 65° F, although southward the temperature is somewhat lower as at Valparaiso, where it is only 58° F. At the latter place, the mean monthly temperature varies from 63.5° F in summer to 52° F in winter, and the thermometer seldom rises to 85° or falls below 38°. Santiago at an altitude of 1,740 feet has recorded extremes of 96° F and 25° F, and on rare occasions snow falls in the city. At Valdivia in the southern end of the central valley, January is the warmest month with 61.5° F and July the coldest with 45° F. Due to the winter rainfall and the attendant cloudiness, the sensible winter temperature is much lower than the records indicate ; and the general consensus of opinion is that, in spite of its excessive humidity, the climate of the inhabited parts of the country is conducive to health.

Vegetation.

Chile's isolation by desert and high mountain ranges has given it a number of distinct species of plants not found elsewhere. The indigenous flora of Chile, however, does not show the great variety that the wide range in latitude would seem to indicate. Although a goodly part of the country may be classified as lying well within the tropics, yet because of the arid wastes in the north, no part of the Chilean vegetation is to be considered tropical. The north is absolutely barren along the coast from the extreme north to the region of the Loa, but in the oases and along the stream courses there thrives the Algarroba tree (Prosopis) with its tiny yellow flowers in the spring and its nutritious seedpods later, also the Chanar (Gourliea) one of the leguminaceae. One of the more striking is the Tamarugos (Prosopis tamarugo) which gives its name to that stretch of desert. The western slopes of the northern Andes produce certain nutritious grasses besides the tola brush and ichu grass. Farther south the Cacti become common. In Coquimbo, from the sea to the Andes, the quiscales form an effective covering but in addition a variety of vegetable forms thrive and afford some pasturage. In this section also are to be found large numbers of bulbous plants with their showy colourful blooms.To some degree Central Chile presents a transitional flora between the north and the south, but it also has a number of dis tinct species of its own. Among the most familiar of these are the Espino (Acacia) with its twisted limbs especially prized for the excellent charcoal made from its wood; the Colihuai (Colli guaya) with its milky sap; and the thorny Trevu (Trevoa) one of the rhamnaceae. Mixed clumps of these give a safe asylum from grazing livestock to a host of tender flowering plants. The ever green largely predominates here, and the dense dark foliage of the Peumo (Cryptocarya) is commonly conspicuous together with the Quillai (Quillaja) another characteristic evergreen. The Coquito palm (Iubaca) was once very abundant but has been almost com pletely destroyed by collectors of its sweetened sap. One of the most striking trees is the Pinon, Chilean pine (Araucaria imbri cata), which often grows to a height of too ft., and is highly prized by the natives for its nuts, which are small but have a very attractive flavour.

When the Spaniards first visited Chile, the southern forests extended northward to the region of Santiago; from here on north was the semi-arid bush land. The good lands now have been cleared. The true forests of Chile may be said to be south of the Bio-Bio; rough estimates of the timbered areas vary from 40, 000,000 to 5o,000,000 acres. South of Valdivia is a vast forested region of which little information is available. Among the domi nant types of commercial woods are the various species of conifers (Podocarpus, Araucaria, Fitzroya, Libocedrus) ; the laurels (Billota, Cryptocarpa, Persea) ; the magnolias (Drimys) ; and the beech-like group (Notho f agus) of many local kinds and names. Trees become smaller and more stunted to the south, until at the Straits of Magellan only shrubs prevail and the altitude of the tree line is below 2,00o feet.

Fauna.

The animal life of Chile is limited to relatively few forms. Both the north arid region and the south humid region are unfavourable to the development of many species or numbers. The largest of the mammals, the pangi or puma (Felis concolor), extends its range down to the Straits of Magellan. Of the three species of wildcats the guina and the cob are the most common; of the foxes, the chilla (C. azerae) is small and considered stupid, the culpeo (C. magellanicus) is much the larger of the two; and of the other smaller forms the coypu, or nutria, sometimes called the South American beaver, and the chinchilla (Chinchilla naniger) are the most important because of their excellent furs. The last named with its much prized skins is fast disappearing. Of the ruminants, the Guanaco, one of the camels closely related to the llama, although a plains animal, is now found only in the moun tainous areas. The deer are small and nearly extinct. The huemul (C. chilensis), appears on the Chilean escutcheon, and the pudu, a small animal with branching horns is found only in the south, especially on the island of Chiloe. The bird life is much more abundant. The hawks and owls seem especially numerous. Un usually rich is the southern part of the country in wading and swimming birds, especially geese, ducks, swans, cormorants, ibises, bitterns, rails, red-beaks, curlew, snipe, plover and moor hens. The smaller singing birds are found also in great numbers.(W. H. Hs.) Population.—Quite commonly Chile is spoken of as a "white man's country." This is true when compared with the plateau countries to the north, but the qualification is more a matter of class than of blood. There was abundant opportunity for mis cegenation during the colonial period as the fierce Araucanian remained unconquered for three centuries and the conflict with him called for an endless succession of Spanish soldiers, who in turn left in their wake a large number of half breed children. From such unions came the foundation of the Chilean race. The mixture occurred so long ago that its results are now expressed in racial unity and common characteristics and are quite un noticed in the country itself.

The Chilean population is definitely divided into two classes, those who do, and those who do not possess material and cultural wealth. To some degree the dis tinction is the result of racial admixture but more definitely it ' arises from differences in inherit ance, in opportunity and in out look. Nominally independent and working for wages the roto, or agricultural labourer, lacks vision or initiative. The patron, or land lord, who profits from his labours may, as landed proprietor, be a gentleman of culture, and of suf ficient wealth to supply his own requirements and to educate his children abroad. He rarely seems to care how wretched his in quilinos (tenants) may be, al though nearly always ready to help in times of special adversity.

In the south are the Araucanian Indians who proved such valiant and unconquerable foes during both the Inca and Spanish regimes. Their definite overthrow as an independent people came only in 1882 when seasoned troops from the battle fields of the north pushed through the frontera and put an end to their re sistance. The Araucanian strain in Chilean blood is considerable although not as noticeable as the blood of other tribes for it has not resulted in deterioration. Pride in the Araucanian heritage is reflected even in the national anthem. About 8o% of the Indians (105,000 in 192o) live in the provinces of Malleco and Cautin. Beyond lies Valdivia and Llanquihue. It is in this region that German colonists of the mid-century encountered extraordinary hardships. But they introduced much-needed handicrafts, iron and wood working, tanning, shoe making and the like, and soon drew large numbers of Chileans to their settlements. The Ger manization of south Chile has not been a matter of sheer numbers but is due to a far reaching cultural influence that if more wide spread might prove a great blessing. In the extreme south one still encounters some remnants of the Fuegians, an indigenous people of extremely low culture.

In other parts of the country a plentiful sprinkling of English, Irish and Scottish names denotes an infusion of North European blood that is still going on, while recently arrived Spaniards, Italians and Slays bespeak a continued connection with South Europe. Chile has never attracted a large immigration. Only 2,851 naturalization papers were granted from 1890 to 1926, although this low average—about 77 per year—does not represent the total number of new comers. Of those nationalized the Ger mans were first, with 722, the Spaniards second, with 382, and the Peruvians third, with 365.

In the north the "Changos" may represent survivors of an earlier native stock. The nitrate plants have attracted some immigrants from Bolivia, who are not regarded, however, as particularly welcome or efficient labourers. Chile is now making an effort to bring back to its soil those expatriated citizens, esti mated, but probably inaccurately, to number 120,000, who are largely located in southern Argentina. They are offered free lands and other inducements to settle in the newly created territory of Aysen. The slow increase in population is a cause for concern to the authorities. The surplus of births over deaths in 1921 was and for 1925, 47,438. For the latter year the illegitimate births were reported as 36o out of each 1,000 born.

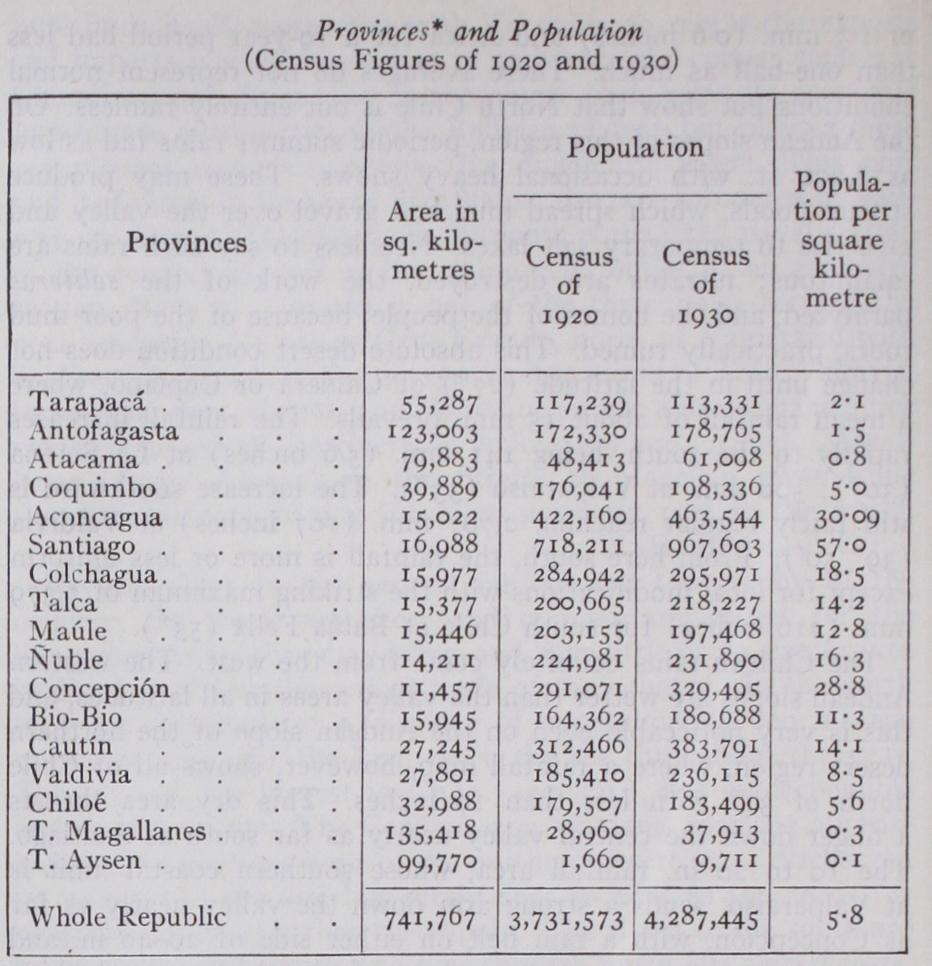

*This table represents the new distribution of territory established in 1928. In that year the former province of Valparaiso was annexed as a department to Aconcagua and the former province of Llanquihue was made a department of Chiloe, while the territory included in the old provinces of O'Higgins, Curicb, Linares, Arauco, and Malleco was divided among the neighbouring provinces. At the same time the new territory of Aysen was created from the lower part of Llanquihue and upper Magallanes. The populations here given for 1920 are for the present provincial boundaries.

experimenting for more than 3o years with a pseudo-parliamentary government, Chile in 1925 reverted to the "presidential" type. The constitution adopted in that year provides for direct elections, for suffrage and citizenship without class distinction, for the separation of Church and State, and for an independent president. It is evident from recent events that its success will depend more on direct action by this official than on strict constitutional procedure.

Technically Chile is a unitary republic with responsibility cen tralized in the president. He is. elected for six years and is not re eligible. Colonel Carlos Ibanez was unopposed when elected as president of the republic in May, 1927, after having served as acting vice-president for a few months and after having for some time before that virtually directed government policy. A series of defalcations in the revenue districts, the growing deficits in the State railways and the increasing costs of the civil service gave point to his policy of retrenchment, reform, and increased productivity and led to a general acquiescence in the more arbitrary features of his rule.

The validity of a president's election is finally determined by a special tribunal made up of former presiding officers of the senate and chamber of deputies and members of the supreme and appel late courts. The president selects the members of the supreme court from a list of five proposed by the court itself, designates members of the courts of appeals, of which there are eight, from lists submitted by the supreme court, and appoints judges of first instance from lists submitted by the court of appeals in the juris diction concerned. He cannot remove judges but he is empowered to transfer them, when necessary, within the jurisdictions to which they belong. Judges are removable by a two-thirds vote of the supreme court.

The president names the intendentes of the provinces, the gov ernors of departments, and alcaldes in municipalities or communes of more than 1o,000 inhabitants. He also has the power to remove these officials and indirectly controls their subordinates. A new code is under consideration, which is designed to decentralize the system still further and to give greater power in local affairs to the intendentes and governors. The taxpayers are empowered to name communal committees (juntas de vecinos), non-political in character, who advise in local administrative and economic mat ters.

Congress consists of a senate and chamber of deputies. The former is composed of 45 members, five from each of the nine groups of provinces into which the republic is divided. Each senator holds office for eight years, and half the seats are renew able at the end of four years. The chamber of deputies numbers 132 members, one for each 30,00o inhabitants or major fraction. Electors are registered citizens over 21 years who are able to read and write. The ordinary session of congress lasts from May 2 r to Sept. 18. It passes on the budget but the president may increase or decrease items within the limits therein prescribed, but congress may by a two-thirds vote pass a bill over his veto. Members of the cabinet are ineligible for seats in congress, but may speak in its sessions. They are subject to impeachment by congress and to removal from office for cause.

Credit and Finance.

Chile's financial record has in general been creditable. The relatively large expenditures have been main tained by the nitrate revenues and the recent decrease of income from that source was little short of disastrous. Moreover for 3o years past the government has struggled with the problem of stabilizing its currency. The disturbances of 1924 and 1925 made further delay impossible. Acting upon advice of the Kemmerer commission (see below, History) the government adopted legis lation which established the paper peso at a gold valuation of 6 d. (in place of the fanciful 18 d.), established a Central de Chile with the exclusive right to issue paper money and with the power to regulate general credit, and placed the general banking interests under the supervision of a Superintendent and central commission. This central bank received from the government the conversion fund of 409 million pesos that it had been accumulating for 3o years and with the aid of this sum established its own credit, replaced a large portion of the outworn paper money, and met the difficulties caused by the business and political slump of 1926. The bank follows the Federal Reserve system of the United States and in its two years of operation has reduced by a third the discount rate for banks and for the public, has acted as fiscal agent for the government and as a general clearing house, and has kept within narrow range the fluctuations in exchange, besides showing a substantial profit.The government has definitely bettered its own fiscal affairs. At the end of 1926 it faced a prospective deficit of 161,500,000 pesos. By cutting salaries and pensions, and reorganizing the system of internal revenues, in which extensive defalcations were discovered, and of the customs ; by rigorously applying the tax laws and adhering to a fixed budget, the situation was greatly improved and with some recovery in general business and a foreign loan the year 1927 ended with a slight balance. The income for 1928 was estimated at 959,119,617 pesos.

The treasury-general in the Ministry of Finance now controls all receipts and expenditures throughout the country. A new officer, the controller general, audits all accounts. A new depart ment of the ministry maintains close relations with the producers of nitrate and with mining. This is in keeping with the new policy to encourage business by tariffs, by shifting the burden of tax ation and by undertaking public works. In accord with the last named policy, the government proposes for the next six years an extraordinary budget of 1,575,000,000 pesos to be raised by loans and to be devoted to railroads and highways, port and irrigation projects, water supply for cities and public buildings. In addition it has authorized a farm loan fund and an institute of industrial credit.

Education.

The present system received its initial impulse about the middle of the last century. To the efforts inaugurated by the notable publicists of that period were added the laws of 1879 and 1889. This combined legislation represented a com mendable programme for the better classes and the cities. Within recent years, however, there has developed an insistent demand for the education of the unlettered country population and for im provements in the existing system, especially in the direction of practical training. The State has accomplished something in the matter of technical and commercial training and during recent years the Catholic University at Santiago and the Laical Univer sity of Concepcion have substantially broadened higher instruc tion. Since 1920 the demands for reform have occasionally ex pressed themselves in extended student strikes, which likewise re flected the prevailing unrest. In response to this agitation, which was supported by a few substantial leaders and by an increasing number of educators who had been trained abroad, a commission was appointed in 1925 to draft a comprehensive programme. This plan, somewhat simplified in the ministry, was issued by decree in May, 1927. It aims to decentralize the administration of primary schools by placing more responsibility on the provinces, to sepa rate the administration of secondary schools from that of the uni versity, and to give the latter more freedom ; and at the same time to integrate the system through councillors from its five (originally eight) branches, who represent the president, the ad ministration and teachers, and related activities. The minister of education is to superintend the entire system. Originally it was planned to have this f unction performed by a separate, non political appointee. The departments of the ministry are as fol lows : (1) the sub-secretaryship ; (2) primary education; (3) sec ondary, humanistic and technical education; (4) university educa tion; (5) artistic education and extension work. The councillors of these divisions exercise legislative and regulatory powers, while the directors of each, who confer with the minister, execute de tails and select personnel.In 1920, out of a total population of 3,753,799, were re ported as able to read. This may be a liberal estimate, but it is about four times larger than in 1854. In 1924 67.2% of the esti mated scholastic population (6 to 14 years) of 888,683 were re ceiving instruction. This marked an increase of about 13% since 1918. Under State auspices, 510,145 were receiving instruction distributed as follows: 449,697 in primary schools, 55,760 in sec ondary schools, and 4,688 in higher institutions. Marked increases in all grades of instruction, public and private, characterize the past few years, except in normal and special schools. The new magnificently equipped Instituto Santa Maria of Valparaiso, a private college of engineering, made possible by a legacy from the late Federico Santa Maria, is a hopeful sign of awakened interest in Chile's educational needs. So is the recently completed na tional library, which reports a commendable list of general activi ties, in addition to the collections maintained for consultation, and the Club de Senoras of Santiago, which stimulates a healthy activity among women of the upper class. There were reported in 5924 627 periodicals of various types, of which 1o1 were of daily issue. Among these were an encouraging number devoted to professional and scientific interests and to social and labour propaganda.

Social Conditions.

Labour organizations before the loth century were of the beneficiary type. The pioneer was the graphical Union organized in 1853 and unions of this type, resenting commercial and bank employees numbered 240 in I 900 ; in 1925, 60o with 90,00o bers. After 190o, the workmen began to group themselves more definitely for defence and in 1909 organized the "Labour Federation of Chile" with provincial, partmental and federal councils, which took definite part in strikes in the coal region and in the nitrate fields. Its programme braced mutual aid, propaganda against alcohol and in behalf of education and an eight hour law, for arbitration of disputes, and for amicable relations with the public authorities. At its annual meeting in 1917 measures were taken to include in its ship all classes of labourers without distinction of sex. The eration in 1919 adopted a programme that was frankly munist. In 1921 it adhered to the Third International and reorganized on the basis of six industrial councils (foods, manu factures, transportation, construction, public service, mines). Much of its programme was embodied in the social legislation of 1924-26.Among other organizations represented in the country is the I.W.W. (Industrial Workers of the World, q.v.) especially strong among port labourers, the various unions of trainmen, a federa tion of printers, and a Catholic Federation of Labourers. These organizations, with exception of the first, are usually dubbed "yellow" by their more radical fellows, because of a tendency to cooperate with the government, while those that simply empha size beneficiary measures are dubbed "white." Since 1920 all types of these unions have abandoned the policy of abstention from politics. In 1926 the anti-capitalist groups formed the Union Social Republicana de los Asalariados de Chile (U.S.R.A.Ch.) with the purpose to work for the "spiritual, social, political, and economic emancipation" of the employed class and for the or ganization of "a new society, based on justice, cooperation, and solidarity." This organization displayed increasing activity in political affairs until curbed by measures of the present president.

Up to 1924 employees were protected by general principles of law under the Code of 1857 and the commercial Code of 1867. Occasionally some organization was given definite juridical status. The I.W.W. lost this through resort to violence. About 1922 the Radical Party, representing the middle classes, began to favour legislation to put relations between capital and labour on a legal basis. The result was the law of Sept. 8, 1924, which created a series of general unions on a syndicalist base—the Union de Em pleados de Chile (U.E. Ch.) . This followed the tendency toward collective action shown during the preceding 15 years in the capi tal and the chief industrial centres. Its social tendencies appear in the formation of a Credit Bank, of a Cooperative Association, and of a Mutual Building Association. Its programme, since elaborated, is that labourers should work for their own emancipa tion, which means a living wage, an eight hour day, equal pay for men and women, and the nationalization of industry.

The primary and secondary teachers each have their separate professional organizations, and the former has occasionally shown a tendency to ally itself with elements opposed to the existing regime. The members of the medical profession, the engineers, and the architects have societies that occasionally assume a syn dicalist attitude, although the Medical Society of Chile is strictly scientific and professional in its attitude. In 1921 the employers formed the Associati6n del Trabajo de Chile, for which they im mediately obtained government recognition. Their object is to co-ordinate and give solidarity to all measures "in questions which relate to labour or affect the natural evolution of industry, agri culture, and commerce." Both individuals and corporations may belong to this association.

Since 1900 there has been a growing interest in the labouring classes. A few leaders have directed their efforts to amelioration rather than prevention of specific evils, as is shown in "League against Alcoholism" and various agencies to care for destitute children. Of similar character were government measures against disease—measures which though largely unobserved date back to 1892. In 1906 the government passed a law for working- class housing, which marks the first intervention by the government in a strictly social question. Later laws in favour of rest on Sunday (1907), the creation of the Office of Labour Statistics (5907), of laws for National Savings Banks (1912), for the care of aban doned infants (1912), for the regulation of conditions of labour including the labour of women and children, and providing for insurance against accidents (1912-16), on the railroads and in the nitrate establishments, and the law for obligatory primary educa tion (1920), and for a fiscal pawnshop and for regulating mari time and other tasks, all point in the same direction. These cul minated in the Decree Law of Sept. 8, 1924 which initiated a veritable era of social legislation. This regulated labour contracts, the day's work, salaries, hygienic conditions, conditions for women and children, security, arbitration, syndical organization, and methods of cooperation. Later laws created a special ministry for carrying out these enactments, which, however, has not always been accorded a separate cabinet position. Much of this legislation has provoked bitter criticism, as being ill-advised and not adapted to those for whom it was intended nor to prevailing conditions in business.

The government also undertook an extensive programme for sanitary betterment. The inroads of alcoholism, of tuberculosis, and of venereal diseases; the extremely high death rate among infants, the lack of and poor quality of water supply and of sewer age systems gave Chile a death rate of about 4o per 1,000 that was hardly surpassed anywhere. Dr. J. D. Long of the United States Health Service in 1925 revised and put in force a sanitary code that put Chile far ahead of its neighbours. Among conspicu ous features of his campaign was a widespread attempt to stamp out the pest of flies, to prevent commercialized prostitution, and to purify the water supply of the larger cities and give them bet ter markets, a supply of pure milk and improved drainage. With the assistance of a group of local helpers much was done to im prove conditions, despite the ever present financial shortage. This betterment has shown itself in a lowered death rate and in a marked appreciation of the dangers that menace the country through inadequate sanitation. As in the case of labour legisla tion, however, much of this legislation has proved too advanced for the people. (I. J. C.) Mining.—In few countries are the activities of the people so restricted to certain regions as in Chile. Of these divisions none has its characteristics more sharply defined than the northern desert area with its unusual mineral riches, especially nitrates, which came into the possession of Chile as a result of the "War of the Pacific" (1879-83).

The nitrate beds lie between 19° and 26° S. and are found on the upland or "pampa" lying behind the coastal range at altitudes varying from 4,000 to 9,000 ft., but practically all the oficinas or nitrate works are below 7,500 feet. The workable beds, with a concentration of from 12 to 4o% sodium nitrate, are non-continuous and vary in thickness from about 8 in. to 14 feet. The ordinary workings are by the open pit method and use only the richest caliche, or ore, so that unit areas produce variable amounts.

Of caliche mined only 55 to 75% of the sodium nitrate is recovered. A new method—the so-called "Guggenheim process"— promises a more complete recovery of nitrate, together with a considerable reduction of costs. The latter is effected by mining both high and low grade ores on a large scale and by reducing the product at a lower temperature. Running tests have shown a 94% recovery in caliche of 1o% grade.

The origin of these immense deposits is more or less conjec tural. The theories roughly fall into two groups, the organic and the inorganic. The origin through organic means are (1) from sea weed, (2) from guano and (3) from fixation of atmospheric nitrogen by bacteria. However, none of these theories is taken very seriously at the present time. The inorganic origin has been attributed to (I) the electric fixation of atmospheric nitrogen, and (2) to the concentration of the nitrates coming directly from tuffs and lava flows. The latter postulates, probably the more scientific, present fewer difficulties. Of this group, two theories stand out most prominently. The one (J. T. Singewald, Jr., and B. L. Miller: "The Genesis of the Chilean Nitrate Deposits," Econ. Geol., XII., 1917) "is that the nitrate deposits have resulted from the accumulation, by means of evaporation of the minute nitrate content of the underground waters of the region. In other words, they represent a sort of efflorescence of soluble salts out of the ground water." The other (W. L. Whitehead : "The Chilean Nitrate Deposits," Econ. Geol., IX., 1920) and later suggestion is that the source of the salts is from the Mesozoic rocks of the region which in extent correspond remarkably with the nitrate fields. Ammonium salts were probably sufficiently common in the volcanic rocks of the region to account for the present deposits. The process of reconcentration, through oxidation with alkaline earth, has been going on since early Pliocene time. Under desert conditions the salts derived from sources on steep slopes and hill tops were carried down by dews, fogs, or infrequent rains to be deposited during evaporation in the gravels below. Here in periods of high humidity, sodium nitrate, a deliquescent substance, was separated from the accompanying sodium chloride and sodium sulphate, to be precipitated during dry weather lower in the gravel.

The importance of these deposits to Chile can be gauged with little certainty. It has been estimated that between 188o and 1910 Chile derived from the export tax on nitrate alone an average annual income of $1o,000,000 gold and since then one of twice that amount. For many years this nitrate trade has constituted more than half the total value of her exports, and the tax thereon of $10.60 U.S. gold per ton collected by the government has con stituted not only the largest item of its revenue, but also for many years has exceeded all other revenues combined. The prosperity of the whole country and the financial condition of the national treasury are to a very large measure determined by the condition of the nitrate industry. The nitrate fields, which in ordinary times give employment to over 40,000 workmen, offer one of the chief markets for Chilean produce. The annual output is upward of 2,000,000 tons valued at nearly $ioo,000,000 U.S. gold. The effect of this easily acquired wealth, especially during the earlier years of the industry, is believed by many to have been actually harmful to Chile's sound development. The tendency to use this money for other than wealth producing investments has hindered the development of agriculture. Both capital and labour have naturally sought the more remunerative rewards of the nitrate regions. Since the World War, however, Chilean producers have been experiencing the reaction from the boom days of that period and have encountered keen competition from the manu facturers of synthetic nitrates. Some slight improvement in production after 1922 was followed by another decline that cul minated in the disastrous year of 1926. Since then there has been a slight recovery, but Chile has failed to profit greatly from the increase in the general consumption of nitrate. In 1926 the country produced only about 25% of the world's nitrogen require ments, as contrasted with 64% in 191o, although from its nitrate reserves it could supply the world for several centuries. With free competition in selling, with a reduction in the export tax, and with the advantages offered by the "Guggenheim Process" in the working of low grade deposits, Chile, it is confidently believed, can compete with synthetic nitrate for many years to come.

In addition to nitrate, Chile is also rich in low grade copper deposits. Some of the richer ores were worked by the Spaniards as early as 16o1 and by the Indians long before. In the latter half of the nineteenth century, Chile was a leading copper centre of the world, in 1876 producing 38% of the total supply. With the development of the copper deposits in the United States, Chilean production fell off to only 4% of the world total in 1906. Its rise in more recent years has been rapid and it now holds third rank with abundant prospects that it will at least retain this position. About 90% of Chilean copper is produced by two large American companies, operating at three centres : one in the north at Chuquicamata, another near Rancagua at El Teniente, and the third at Potrerillos near Chanaral. The Chuquicamata is one of the large scale mining operations in the world, working a low two per cent grade ore at an expense of seven or eight cents per pound. The copper reserve, the largest known, is conservatively estimated at 134 billion pounds. Although Chile's high grade iron reserves are estimated at over 900,000,00o tons, production of pig iron is almost nil due in large part to a lack of coking coal. Only one of the deposits, that at Cruz Grande, in the province of Coquimbo is being exploited and shipped to the United States under the control of the Bethlehem Steel Corporation. The mining and loading on steamers of this ore, on an unusually large scale, is considered a model of efficiency. Because of high grade and cheapness in its handling, these ores enter into competition with the great deposits in the United States.

The coals of Chile are noted for their quantity rather than their quality. They occur on the coast south of Concepcion and are of Tertiary age. They vary considerably in quantity, improv ing with depth. The product has been described as second class steamer coal, on the average 25% inferior to the Welsh product. There are four principal coal fields in the vicinity of the Bio-Bio, of which the most important, Coronel and Lota, are worked under the sea by means of inclined drifts (chiflones) on the long wall system. In addition there is a small lignite deposit near Ma gallanes mined only for local use. Four-fifths of all the coal mined is used by the State railways and production in recent years, some what over a million tons annually, has been adversely affected by the increasing use of petroleum.

Agriculture.

The agriculture of Chile is confined almost wholly to the central valley. The available productive land is extremely limited, the amount devoted to cereals and other food crops being estimated at not more than four per cent of the total area of the country; orchards, vines, planted woodlands, grasses, and alfalfa (lucerne) occupy a somewhat smaller area; and the natural pasturage occupies a smaller area still. This io or 12% of the area, together with the 20 to 22% in natural forests and woodland, mostly in southern Chile, makes up the productive land—about 3 of the total area of the country. The leading crops with their average acreage for 1921-1925 were wheat, 1,457,000 ac. ; barley, 148,000 ac. oats, 95,000 ac. ; corn, 62,00o ac. ; flax, 675 ac. ; making a total of only slightly more than one per cent of the total area. Even with the acreage (about 275,00o ac.) devoted to grapes and orchards, these crops make up less than two per cent of the total.By far the major part of the crop land is made possible only by irrigation, which was practised in limited areas of northern Chile, even during prehistoric times. The chief areas now under irrigation lie along the river terraces within the Cordillera, upon the piedmont to the west, or within the central valley. The avail able streams from the Loa to the Bio-bio are the chief sources of water. Some of the irrigation projects are of long standing and on a large scale, and carry water in canals over 10o m., besides furnishing extensive electric power. Many of the undertakings are privately owned, others belong to associations, and in recent years some very large projects have been financed by the government. The area served by the three largest canals aggregates 3oo,000 acres.

Although agriculture in the central valley lays the foundation for the social and political structure of the country and affords a large share of the products for local consumption, it has little influence on trade balances. Socially the bulk of the people are organized around the large feudal estates and suffer little change in condition whether crops are good or bad. The owner may be more or less affluent from year to year, but this adds little to his comforts or discomforts, and he always remains on the social and political register of the country. In the northern valleys maize is the chief food crop and besides there is a great variety of sub-tropical fruits. The best developed type of feudal estate may include some 250 ac. of irrigated fields and 2,000 ac. or more of hillside land, which offers excellent range for live stock during the rainy season. These dades agricolas are mixed farms producing a large variety of grains and fruits, and alfalfa, some horses and a larger number of cattle and sheep, but never many hogs. The growing of live stock on irrigated land, however, is not profitable. As a result Chile has less than half the cattle of Cuba and must depend upon Argentina for part of its meat supply. This source, owing to recent tariff changes, is being still further restricted. The tively large number of sheep is accounted for by the big ment in Magallanes where more than one-half of the sheep of the country are found. The central valley, so similar to that of fornia, favours the growing of fruits, but lacks a good market. A number of attempts have been made to develop one in the United States but shipments there, with a few exceptions, have not been successful. The chief gain of the Chilean farmer has come from his vineyards. The wine of the country is widely known out South America. The grape acreage ranks next to wheat and is larger than that devoted to any other cereal, or to beans or alfalfa. Whether this is the cause or not, Chile is considered as more afflicted by alcoholism than any other South American country.

Although south Chile is the great forest section of the country, yet because of transportation problems relatively little of the output enters into its internal or external commerce. On the whole it has been found more economical to import timber products from the United States. Chilean forests were once very much more extensive than now but have been destroyed as an incumbrance, even in late years. Of the forested area, estimated at about 35,000,00o ac., at least two-thirds of it must be dis counted because of the character of the woods or the type of country in which it is found. Only the province of Cautin can lay claim to first class forests.

Manufacturing.

Like other South American countries, Chile has not yet reached the industrial stage, although the Government has done much to stimulate local activity. Most of the manu facturing establishments are little more than workshops, for in the 3,196 factories listed in 1923, there were employed only 82,118 people—an average of 25 or 26 each. By far the most numerous group of factories and the one employing the greatest number of workmen was engaged in the preparation of foods. About one-third of these factories, with nearly one-half the people employed, are in the province of Santiago. Great strides have been made in the preparation of leather and in the use of up-to-date machinery for'the manufacture of shoes, so that Chile is now largely supplied from the local output. The high tariffs of recent years have also done much to stimulate local production, espe cially of textiles. Much may be expected from the development of electrical power.

Commerce.

Although Chile ranks seventh in size among South American republics, it stands third in the value of its foreign commerce, being exceeded by Brazil and Argentina only. Its per capita trade, about $100, is equal to that of Argentina and double that of Brazil, although only one-tenth the total of the latter. This is a striking result, for fully one-half of the population is made up of agricultural rotos, who are modest consumers.By 185o England, France and Germany had largely crowded Spain out of Chilean tfade, and Valparaiso had become the leading port of the west coast. Lines of communication were developed with California and Australia, and the trade of Chile became a vital factor in its development. Gradually copper and silver became more important as exports. The nitrate deposits were opened up, but this trade was of slow growth until after the "War of the Pacific." In 188o nitrate accounted for 30% of the Chilean exports, and in five years this increased to 6o%. From then on up to the World War, the exportation of nitrate grew rapidly and made Chile rich. The years just preceding the war were banner years, due largely to the cumulative effect of mount ing revenues, to which seemingly there was to be no end. This naturally encouraged a lavish expenditure of money.

The outbreak of the war and the blocking of the trade channels brought on a national crisis of unusual severity. Then as the war progressed unprecedented demands for nitrate and copper in the United States, together with the opening of the Panama canal (1914), brought to Chile a prosperity never before equalled. In three years the trade more than doubled and the export figure reached the high mark of $278,000,000. With the close of the war, the market collapsed and the exports fell to the pre-war figure. Then with the short post-war boom the export trade reached the new height of $284,000,000 for 1920. But hard times followed, the country passed through one financial crisis after another, the government changed hands, and in 1927 the people submitted, in an earnest hope for a return to former prosperity, to the control of an army dictator. The abandonment in April, 1927, of price-fixing by the Association of Nitrate Producers has brought about some renewal of activity in that trade.

The situation with respect to nitrate is unique. Although agricultural activities are vitally important to the bulk of the population, the economic position of Chile in world markets depends upon its mineral resources, which account for the major part of its exports, and indirectly furnish the funds for most of the imports. The prosperity of the people, therefore, depends on an export trade, in which they take little part and over which they have little control. The dominance of the mineral products (more than 90% of the total) in export trade in 1921-23 is shown when nitrate accounts for 58% of the total, copper 21%, borax 3%, and other minor items of two per cent or less make up the rest.

The fluctuations of copper, the second largest item of export, have relatively little influence on the general prosperity of the country, as that commodity pays a local impost rather than a direct export tax. Practically all the export of iron, about 1,000, 000 tons, comes from the Tofo mines, under the control of the Bethlehem-Chile Iron Mines Company.

After various minerals, mutton and wool rank first as exports. Their combined value in the total trade is exceeded only by nitrate and copper. Fully four-fifths of the sheep output comes from the hinterland of Magallanes and hence figures slightly in the trade of Central Chile. Of the other exports, wheat and flour fluctuate greatly from year to year, but average about 4% of the total export. The margin above the home demand comes only with a crop that is above normal. In certain years there is a slight exportation of barley, oats, peas, lentils, fruits, nuts and the like. The analysis of the trade clearly shows that a nation depending on minerals for 90% of its exports is one whose pros perity is not built on a firm foundation.

The import trade is largely made up of manufactured goods and may be grouped into three dominant classes: (1) iron and steel products, about 3o%; (2) textiles, 25%; and (3) a host of miscellaneous products. In the import trade, nearly one-half (48% for 1922-24) of all products come from two countries, the United States and Great Britain. As with almost all South American countries, there is little interchange with neighbouring countries. One of the strong features of the trade has been its regular balance in favour of Chile, but on the whole the outlook is not particularly alluring. The remedy seems to lie in the estab lishing of a new class of small farm holdings under the control of enlightened rotos. With such a change in social order, there may arise a new industrial and commercial Chile.

Transport.

Railway construction started in the north under private auspices in 185o. The government road from Valparaiso to Santiago was first opened in 1863 and thereaf ter gradually extended southward to Puerto Montt. Chile's narrow width called for a strategic longitudinal "system" and the barren character of the country to the northward seemed to place the burden of construction on the government. In 1910 it definitely undertook the building of a line in that direction and the completion of the railroad to connect Arica with La Paz.In spite of this activity, by which 61%, or 3,772 m. out of a total of 6,209, are State owned, the major portion of the northern railways are operated under private ownership or lease, and serve the mineral interests of that region. The Chilean railways are government owned primarily for strategic reasons. In accordance with the treaty with Bolivia, measures were under way in 1928 to turn over to the latter country that portion of the railway within its limits.

Those roads that are under private control are on the whole efficiently administered. The State owned roads, which up to 1926 uniformly showed a deficit and thereby contributed to the finan cial crisis of that year, have been criticised for faulty location, poor equipment, and high operating costs. Political pressure will account for many of these defects, which the present administra tion earnestly seeks to rectify, and to improve equipment on the lines already electrified between Valparaiso and the capital and to Los Andes and the Chilean portion of the Transandine, and to eliminate "graft," favouritism and unnecessary employees. Among the proposals for extraordinary expenditures during t he next five years is one for 183,000,000 pesos for railroads.

Little was done for highways before the law of 1920, which embodies some of the best foreign stipulations. In 1923, 21,959 m. of public road were reported, of which some 3,03o m. were fit for automobiles. Such roads, of course, were near the large cities. Among other extraordinary expenditures the government suggests some 150,000,00o pesos for roads.

The telegraph dates from 1851 and this enterprise, like the rail road and steamship service, owed its inception to William Wheel wright. For some time the telegraph was united with the postal service, then administered separately for about 4o years, and later amalgamated in 1920. It was disorganized during the revolt of 1891 and by the earthquakes of 1906 and of recent years. 16,183 m. of telegraph line were reported for 1924, of which were under private control. A series of wireless stations from Arica to Magallanes (Punta Arenas) is in operation or under construction. In the same year 979 post offices handled 117,495 83 2 pieces of mail.

The sea still constitutes Chile's best highway. Much, therefore, has been done since 1910 in constructing docks, erecting break waters, and in other ways making ports more serviceable, and in directing roads and railways thither. Continuation work of this sort and new undertakings call for an extraordinary expenditure of 287,572,000 pesos during the next five years. A new depart ment of harbour works has been added to the Naval Ministry. Subsidies have been provided for national vessels using the Pan ama canal and the Straits of Magellan and other measures adopted to stimulate a commercial marine. In this branch 13 vessels were reported in 1927 with a tonnage of 19,624. (I. J. C.) Army.—Compulsory military service prevails in Chile. Every able-bodied man over 20 years of age is due to receive 12 months' training, and is, as a matter of fact, very rapidly made into good fighting material. Following the year's active service they belong to the first reserve for 12 years and to the second reserve till the completion of their Soth year. The active army in 1925 consisted of 14,735 enlisted men and 1,513 officers. The first-line reserve numbered about 225,00o men and the second-class reserve about 200,000. The active forces were grouped into four military dis tricts each capable of furnishing a complete division. The army consisted of the following corps : sixteen regiments and three in fantry battalions, eight cavalry regiments, five regiments and six artillery groups, one engineering regiment and five engineering battalions, five battalions of railway troops and two aviation groups. The army has been trained and organized largely on the German system. The spirit of the vast majority of the recruits facilitates the task of able officers. Discipline is good, the uniforms neat and weapons are of modern pattern and well kept. The cavalry, in particular, is conspicuous for its first class condition. The infantry are armed with a modified Mauser rifle, the cavalry with a carbine (of similar make) and lance and the field artillery with Krupp guns. The air service, introduced in 1918 under Brit ish instruction, is being steadily developed. Cadet, artillery, cavalry, engineering and infantry schools are maintained by the State ; in 1924 a school for non-commissioned officers was formed.

(X.) Navy.—The birth of the Chilean navy may be said to have taken place when, in 1817, a Scotsman, Captain William Mackay, set out from Valparaiso in a launch "La Fortuna" and, aided by thick mist and growing darkness, captured a Spanish frigate and a brigantine at anchor in Arica bay. The leader of the patriot forces, Bernardo O'Higgins, followed up this success, and by the autumn of 1818 he had formed quite a useful little squadron.

Two ships, the "Lautaro" and "East Indiaman" (the latter con verted into a 50-gun frigate) and the brigantine "Pueyrredon" had a fierce encounter with the Spanish frigate "Esmeralda" and the "Pezuela," which were blockading the coast. Captain George O'Brien, who came to Chile as mate of a British merchant ship, commanded the "Lautaro," which he ran alongside the "Esmer alda." Shouting "Viva Chile," he placed himself at the head of a boarding party of 25 men and attempted to take the Spanish ship. Unfortunately he was killed, and those that remained of the boarding party were forced into the sea but were rescued by the "Lautaro's" boats. Nevertheless, the enemy suffered severely and fled from Valparaiso.

Not long afterwards, a Chilean squadron, under Admiral Blanco Encalada, attacked and captured a number of Spanish ships in Talcahuano bay. In this enterprise three of the ships of the patriot fleet were commanded by Englishmen.

In Nov. 1818 Admiral Lord Cochrane arrived on the scene and, at the invitation of the Chilean government, took over command of all the naval forces. He had a brilliant record as a fighter and his personal charm and whole-hearted enthusiasm for the cause which he had espoused soon won him the loyal support of the officers and men of his fleet.

Cochrane led his command into a number of daring and success ful adventures, including the assault and capture of Corral. But his crowning achievement was the capture of the "Esmeralda." This Spanish frigate had long been a source of danger and annoyance, and at the time was ensconced behind the batteries and other defences of Callao. Cochrane personally headed the attack, and, in spite of fierce opposition and being badly wounded, he suc ceeded in cutting out the "Esmeralda," taking her to sea, and anchoring her alongside his flagship, the "O'Higgins." By the end of his four years' service in Chile, her fleet had destroyed or captured every Spanish ship on the coast and re duced their base, thus giving the country its independence. His name was perpetuated in a "Cochrane" which, in 1879, under Capt. Latorre, won a famous fight with the Peruvian ironclad "Huascar." The principal units of the Chilean fleet of the present day are:— Battleships I modern, I old.

Armoured Cruisers 2 old.

Cruisers 3 old.

Destroyers 6 building (1928).

Considerable interest is taken by the Chilean people in their navy, and the assistance of British naval officers is sought con stantly to keep it efficient.

In the 15th century the Peruvian Indians invaded the country— even then known as Chile—and dominated it as far south as the Rapel river. (34° 10' S.). Their control may have furthered the later conquest by the Spaniards. The latter made their first at tempt to occupy the region under Diego de Almagro, associate and subsequent rival of Pizarro. Af ter Almagro's death the conqueror of Peru granted Chile to his favourite aide, Pedro de Valdivia. That invader founded Santiago (Feb. 12, 1S41), and of ter estab lishing other fortified towns north and south of that centre and east of the Andes, lost his life in a general uprising of the Arau canian Indians, under their celebrated toque, or war-chief, Cau polican. The greater part of his settlements were destroyed, although La Serena and Concepcion remained as the outposts of the future colony to the north and the south, while Cuyo held the same position east of the Andes.

The Colonial Period.

With this inauspicious beginning Chile entered upon its three centuries of colonial history. In such phases of its development as were affected by the administrative and commercial control of the homeland it differed in no wise from its neighbours. Its population took no part in political affairs, aside from membership in the town councils. It accepted ecclesi astical control in its scant educational facilities as well as in spiritual matters. It endured all the vagaries of Spain's trade restrictions, varied by the piratical and contraband practices of its enemies. Chile differed from other Spanish colonies in that its remote position forced upon the people a more thorough isolation, while continued conflicts with the Araucanians tended to harden the settlers, and the scarcity of precious metals turned them toward farming.By the end of the 17th century this population numbered 100, 000. A century later it approached a half million. This included 300,000 mestizos (mixed bloods), half as many Criollos ("Cre oles," i.e., natives of European descent), some 20,000 Peninsu lares (recently arrived Spaniards, among whom Basque immi grants from northern Spain formed an energetic commercial ele ment), and a smattering of negroes and recently emancipated Indians. This hardy population had progressed far towards racial unity but the mayorazgos, a system of transmitting estates by entail, gave enhanced importance to a few leading families. The people, set down in the midst of resources that were barely touched, were stimulated to activity by a bracing climate, but were pitifully handicapped by ignorance, isolation, and the lack of political experience.

Independence and Self-government.

None of the above conditions that hampered Chile in common with its fellow colonies provoked the movement for independence. Nor was this act due to the rise of the United States nor to the French Revolution. It was the intervention of Napo leon in Spain—an act that in 18o8 threw each part of the Span ish monarchy on its own re sources—that led Chile to take the first halting step toward self government. This occurred on Sept. 18, 181o, when an open cabildo or general town meeting in Santiago accepted the resig nation of the president-governor and in his stead elected a junta (board) of seven members.This act divided the people (not including, of course, the igno rant masses) into two general groups. The first, which was com posed exclusively of Creoles was headed by the cabildo, or town council of Santiago. The audiencia headed the second, which largely represented peninsular interests. The former group wished to organize for local protection during the intervention and pos sibly for more complete self-government thereafter. The penin sulars followed reluctantly, for they preferred to keep intact the existing system which insured them special privileges.

The creole leaders gained their immediate point—a recognized position in the new junta, took measures for the defence of the province, opened its ports to general trade, abolished the audi encia, when that body encouraged a reactionary uprising, and summoned a national congress. By this time Concepcion, under the leadership of Juan Martinez de Rozas, broke away from the conservative leaders of the Santiago cabildo. This split enabled an ambitious popular leader, Jose Miguel Carrera, to dissolve con gress, some two months after it finally organized, banish Rozas, and assume dictatorial powers, but this did not occur before congress had assumed administrative control of the colony, broken relations with Peru, abolished slavery, established a press, en couraged education and suggested further important steps towards self-government—all in the name of the captive king. Affairs in Chile now assumed the aspect of civil war between those of its people who favoured the former autocracy, as represented by the viceroy of Peru, and those who espoused self-government under a more liberal monarchy. Owing to divisions among the autonomists, who called themselves partisans of Carrera or of Bernardo O'Higgins, who had superseded him, the royalists gained the upper hand at Rancagua, Oct. 7, 1814, and brought to an end that first phase of the Chilean War for independence known as la patria vieja (the Old Country).

Two and a half years of repression under the restored govern ment effectually cured the Chilean people of further loyalty to Spain. During this period Jose de San Martin patiently gathered an army at Mendoza and led it early in 1817, across the Andes. With this force, in which O'Higgins commanded a contingent, he defeated the royalists at Chacabuco, on Feb. 12, and made his associate supreme director of Chile. Their first task was to meet the inevitable counter attack under Osorio, the victor of 1814, who surprised and routed the patriot forces at Cancha Rayada. But with a reorganized force San Martin met and crushed the royalists at Maipu, April 5, 1818. This victory made good the declaration of independence which had been formally proclaimed on the first anniversary of Chacabuco.

During the next 15 years Chile passed through a period of political uncertainty that fortunately w4s less prolonged and less anarchic than her neighbours experienced. For five years O'Hig gins maintained a fairly efficient personal rule, slightly modified by constitutional offerings of his own devising. After his abdica tion in 1823 there followed a more unsteady dictatorship under Ramon Freire, which was modified in 1826 by an ill advised attempt at federalism and two years later by the liberal but unworkable constitution of 1828. During this period the Spaniards were finally expelled from Chiloe and that island and the con tiguous area incorporated with the country. Aided by a naval contingent under Lord Cochrane (earl of Dundonald) the Chileans united with other patriotic forces in freeing Peru and thus assur ing their own security. Then followed recognition by Brazil, Mexico, the United States and Great Britain. Through the last named country Chile was enabled to float its first external loan.

In domestic affairs the country was less fortunate. A few social reforms, initiated by O'Higgins and Freire, did little to remove the discontent engendered by years of warfare, to counteract the hos tility of the Church, or to straighten out financial tangles. Politics were almost wholly personal and merely served to reveal political incapacity. Matters reached a crisis in 1829 with the outbreak of civil strife between Freire, who seemed the only hope of liberal ism, and Joaquin Prieto, a successful military chief whom the reactionaries accepted. The conflict was decided at Lircay, April 17, 183o, with the utter defeat of the Liberal forces.