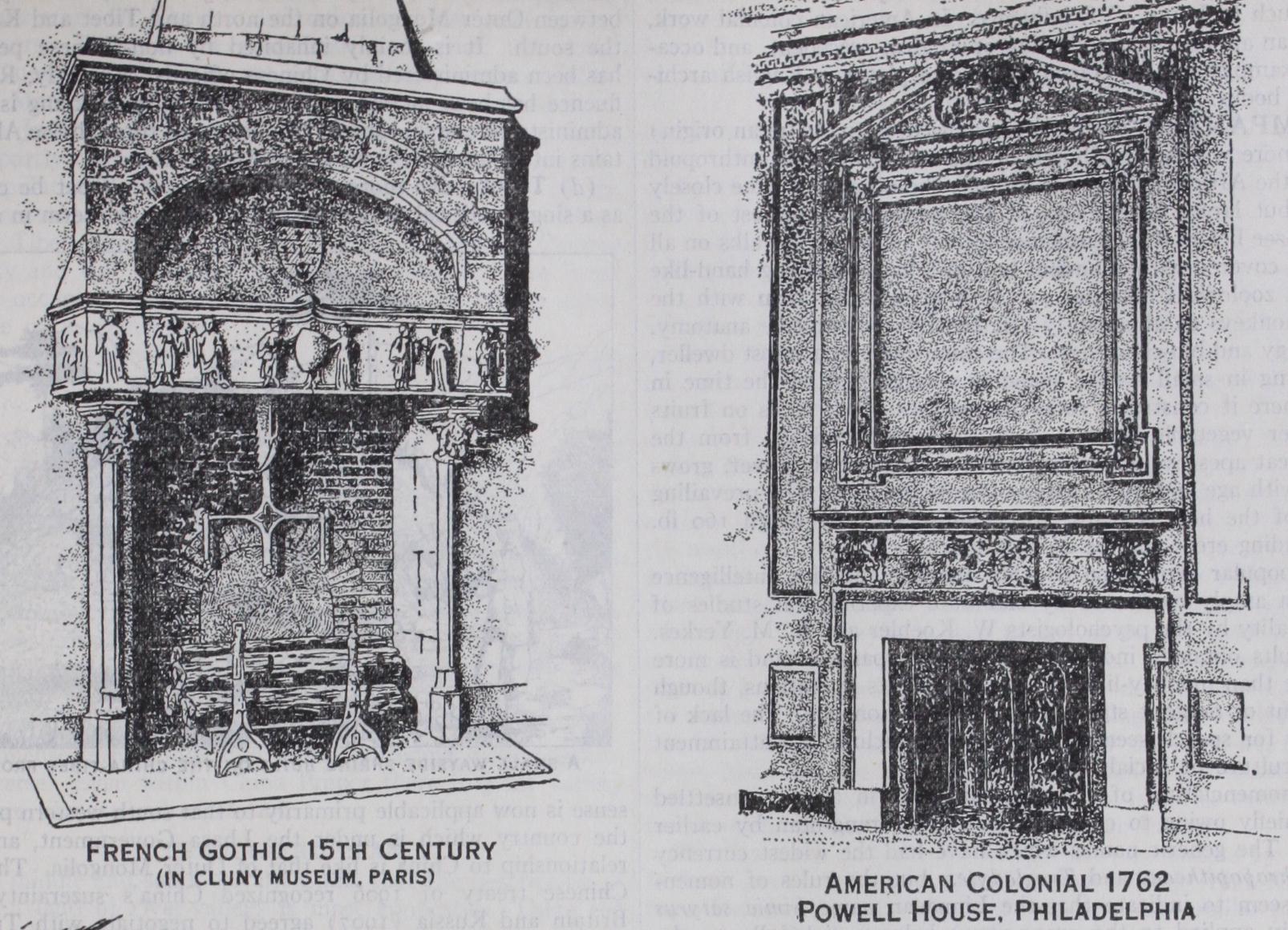

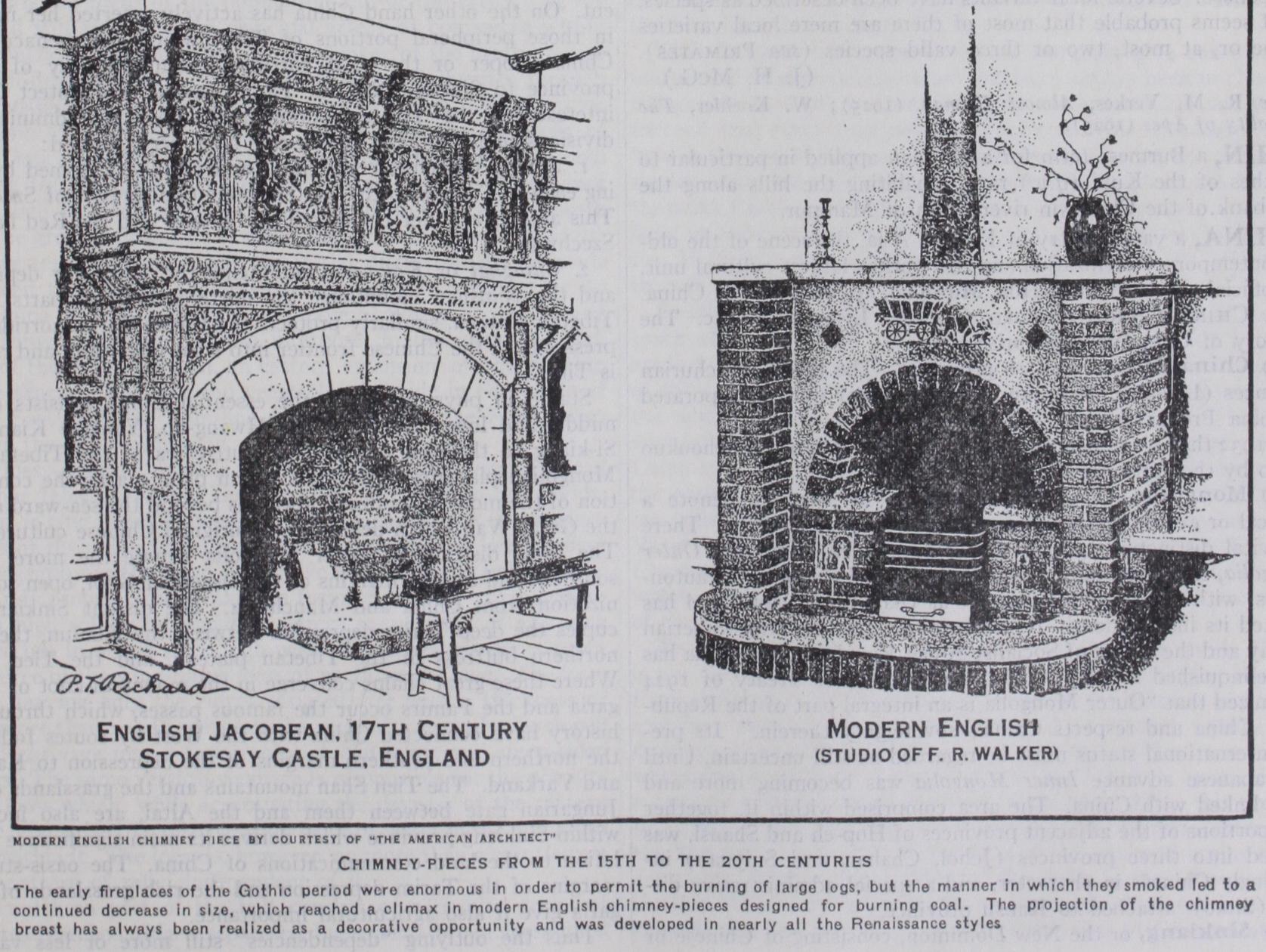

Chimney Piece

CHIMNEY PIECE, in architecture, originally a hood, pro jecting from the wall over a grate, built to catch the smoke and lead it up to the chimney flue; later, any decorative development of the same type or for the same purpose; a mantel or mantel piece. Like the chimney (q.v.), the chimney-piece is essentially a northern mediaeval development. Its earliest form, a simple hood, sometimes with shafts below, at the wall, is shown in the king's house at Southampton and at Rochester castle, England (12th century) . Later, the spaces under the ends of the hood were made solid, so that the fireplace became a rectangular open ing, and in some cases the fireplace was recessed into the wall. Late mediaeval fireplaces are of great size and richness, e.g. the triple fireplace in the great hall of the Palais des Comtes at Poitiers, and the earlier fireplaces in the château of Blois.

During the Renaissance fireplace openings were decorated with columns, pilasters and entablatures, and occasionally the front of the wall or hood above the overmantel was enriched. North Italian palaces are full of examples of great delicacy. In France the fire places at Blois and Chambord are famous. In England, the same formula appears in naïve and complex types, with the usual Eliza bethan and Jacobean melange of misunderstood classic and Flemish motives—strap work, gaines, etc. In France, after a brief classicism under Henry II. and Henry IV., the chimney-piece became a centre of fantastic design. Although the opening was usually small, the decoration was rich, and commonly characterized by the use of a great mirror as an overmantel. The detail assumed the classic extravagance of the Louis XIV. style, the swelling curves and bulbous shells of the Louis XV. and the distinguished restraint of the Louis XVI. styles, but almost always retained the same general proportions and the mirror. German design largely followed that of France; chimney-pieces are less numerous there, however, owing to the use of porcelain stoves.

In England the Renaissance chimney-piece was at first treated, with simple architraves, frieze and cornice, in such a way as to serve as mantel shelf, occasionally with rich panelling above, and much breaking or keying of the mouldings. Later, consoles, caryatides and columns were used, although occasionally a simple moulding of sweeping profile replaced the architrave, and the shelf was omitted. In the last half of the 18th century the char acteristic English chimney-pieces, in the style of Robert Adam, owed much to Louis XVI. influence. In American colonial work, there is an almost exact following of English precedent, and occa sional examples can be traced to definite plates in English archi tectural books.