Gas Analysis

GAS ANALYSIS The general principles involved in the various processes of gas analysis are best exemplified by a consideration of the quanti tative estimation of the constituents of fuel gases, such analytical tests being the chief task of gas examiners. Gasometric methods are, strictly speaking, branches of volumetric analysis, one of the main divisions of quantitative work.

The composition of a gas is usually expressed in percentages by volume, as it is easier to measure a gas than to weigh it. As, however, the volume of a gas depends upon its temperature, pressure and moisture content, all volumes must be compared at the same temperature and pressure and further must be either dry or fully saturated with moisture ; if the conditions under which they are compared are not the same, the volumes in each case must be referred to a standard condition. The standard usually em ployed is the International Standard, in which all volumes are referred to the dry volume which the gases would occupy at o° C and 76omm. of mercury pressure. If V is the volume of a gas saturated with moisture measured at t° C and hmm. of mercury, and a is the vapour pressure of water at t° C (obtained from tables), then the volume V. at the standard conditions is given by the equation Vo=V (h—a) 273/760(273+t). In Great Britain the gas industry is bound by statute to use a different standard, namely the volume saturated with moisture at 6o° F and 3oin. of mercury pressure. Thus if V is the volume at t° F and hin., the vapour pressure of water at t° F being a, then the volume under standard conditions is Vo=V (h—a) r 7.64/(460+t). Tables to facilitate these calculations are given in text-books of gas analysis.

The volumetric analysis of a gas is usually carried out on a small quantity, ranging from 5 to Ioo cu.cm., and if this small sample is to be representative of a large bulk of gas, special pre cautions must be taken to ensure that the sample is properly taken. Whenever the analysis of a sample of gas cannot be made at the place where it is collected, it must be stored in a sample tube with well-fitting glass taps. If the sample is to be kept for some time, it is preferably preserved in a glass tube with sealed ends.

The methods employed in the volumetric analysis of gases are based on: (I) Successive absorption of the constituents by suit able reagents each of which absorbs one only; (2) burning the gas with air or oxygen and measuring the change in volume and the amount of carbon dioxide produced; (3) selective oxida tion by passing the gas over suitable reagents; e.g., heated copper oxide.

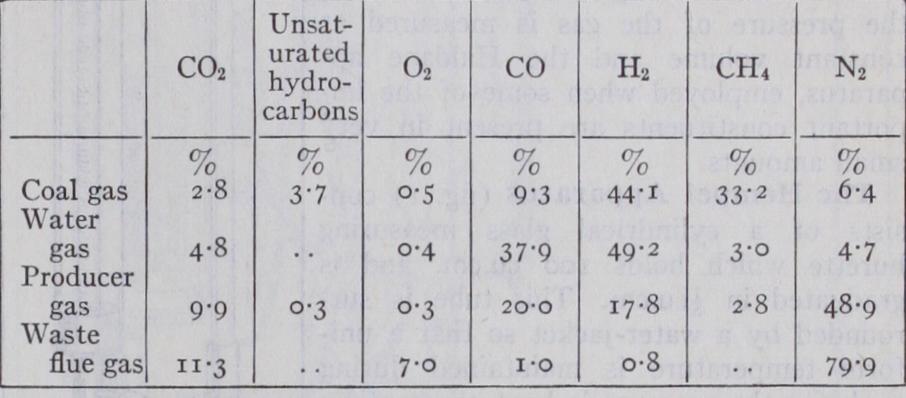

The following are typical analyses of fuel gases: Of these constituents carbon dioxide unsaturated hydro carbons (which include ethylene, propylene and benzene), oxygen and carbon monoxide (CO) are estimated by absorption methods; and hydrogen (H_), methane (CH,) and sometimes carbon monoxide by combustion methods. The nitrogen is usually obtained by difference.

The absorbents used are (I) 25% aqueous solution of caustic potash for carbon dioxide ; (2) bromine water or fuming sulphuric acid for unsaturated hydrocarbons. In either case these reagents must be followed by an absorption with potash to remove vapours evolved by bromine and sulphuric acid ; (3) stick phosphorus m a solution of potassium pyrogallate (I og. of pyrogallic acid dis solved in ioo cu.cm. of saturated caustic potash) for oxygen; (4) acidic or ammoniacal cuprous chloride solution for carbon monoxide—the latter is preferable and is made by mixing 'vol. of ammonia (sp.gr. 0.905) with 3vol. of a solution containing cuprous chloride 2oog., ammonium chloride 250g., water 750g. Two absorptions must be made with the cuprous chloride solu tion, the last one being with a fresh solution. Alkaline pyrogallate and cuprous chloride solutions, which become oxidized and lose their absorbing capacity when exposed to the air, must be stored in the double type of pipette if the Hempel apparatus is being used, the two exterior bulbs being filled with water to prevent access of air.

Certain reagents will remove more than one constituent from the gas so that the order in which the absorptions are made is very important. If the unsaturated hydrocarbons are to be re moved by bromine water, the sequence is as follows : carbon dioxide by potash, unsaturated compounds by bromine, oxygen by phosphorus or pyrogallate, carbon monoxide by cuprous chlo ride. On the other hand, if fuming sulphuric acid is used in place of bromine the order must be : caustic potash, pyrogallate (not phosphorus), fuming sulphuric acid, cuprous chloride. Phosphorus will not remove oxygen from the gas if unsaturated compounds are still present; it is also very slow in action if the temperature of the gas falls below 18° C.

The contraction observed and the carbon dioxide produced when hydrogen and methane are burned together with a known excess of oxygen or air, give a means by which these two gases may be determined, whereas the residual nitrogen is estimated by difference.

When burned with an excess of air or oxygen, 'vol. of hydrogen combines with ivol. of oxygen to form water, which is condensed, so that there is a contraction of z vol.: With methane the reaction is i.e., I vol. of methane combines with 2 vol. of oxygen, forming i vol. of water vapour (which is condensed) and i vol. of carbon dioxide; the contraction is therefore 2 vol. and the carbon dioxide produced is equal in volume to the methane present. When a mixture of the two gases is burned, the methane is A and the hydrogen (C-2A), where C is the contraction on burning or exploding and A is the volume of carbon dioxide formed.

Of the many forms of gas apparatus recommended for these analyses three will now be described in detail—the Hem pel apparatus as a type in which the volume of the gas is measured at con stant pressure, the Bone and Wheeler ap paratus as an example of those in which the pressure of the gas is measured at constant volume and the Haldane ap paratus, employed when some of the im portant constituents are present in very small amounts.

The Hempel Apparatus

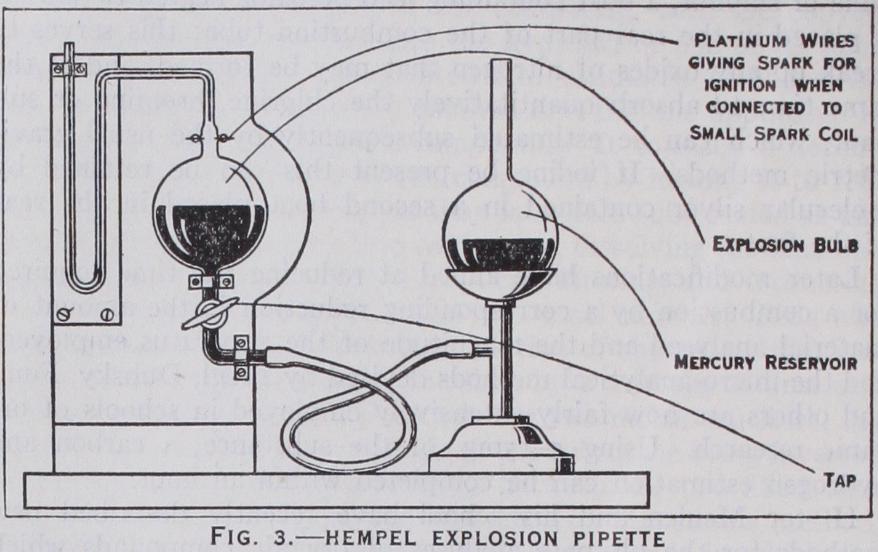

(fig. i) con sists of a cylindrical glass measuring burette which holds ioo cu.cm. and is graduated in 5 cu.cm. This tube is sur rounded by a water-jacket so that a uni f orm temperature is maintained during analysis ; the pressure is kept constant by always taking the measurements under at mospheric pressure which is assumed not to vary while the analysis is being made. The measuring vessel is connected by rub ber tubing to a levelling tube or bottle. Slightly acidified water is poured into the levelling tube and the burette is completely filled by opening the tap at the top and raising the levelling tube, the tap being then closed. The gas to be analysed is drawn into the burette by connecting the top to the sampling tube, opening the top tap and lowering the levelling tube. When sufficient gas has been drawn into the burette, the tap is closed and the volume read, care being taken that the levels of the water in the burette and levelling tube are the same. This ensures that the volume of gas has been measured under atmospheric pressure. The pipette (fig. 2) containing the appropriate absorb ing liquid is then connected to the top of the burette by a glass capillary tube bent twice at right angles. The liquid in the pipette must have been previously brought to the top of the capillary portion of the pipette and the bent tube must be full of water so that air does not enter the burette in the subsequent operations. The gas is driven into the pipette by opening the tap and raising the levelling tube, and is gently shaken whilst in contact with the liquid; when the absorption is complete, the gas is drawn back into the burette and meas ured with the water at the same level in the burette and levelling tube. The loss in volume is the amount of the particular constituent absorbed by the reagent. The operations are then repeated in a similar manner with the other absorbents. The absorptions are usually complete after two or three minutes.Hydrogen and methane are estimated in the residual gas by diluting 15 or 20 cu.cm. to I00 cu.cm. with excess of air or oxygen and exploding the mixture under reduced pressure over mercury in the explosion pipette. This pipette (fig. 3) is provided with a pair of platinum sparking points which are connected to a small induction coil, and the reduction of pressure is effected by lower ` ing the mercury reservoir which is connected by thick-walled rubber tubing to the pipette. The gas is then returned to the burette and the contraction measured. The carbon dioxide formed is absorbed in the potash pipette and this second contraction measured. The hydrogen and methane present in the small amount of residual gas taken for the explosion can be calculated from the formulae given above, and hence the percentages in the original gas are calculated.

The combination of hydrogen, methane and oxygen can be ef fected without explosion by passing them at a suitable dilution into a pipette filled with mercury provided with a short length of platinum wire which can be heated by passing an electric current from dry cells or an accumulator.

Hydrogen can be determined in the presence of methane by passing a mixture of the gas and air through a capillary tube containing palladium wire or palladium-asbestos. The gas is passed several times backwards and forwards from the burette through the gently heated tube into a pipette containing water.

The nitrogen remaining is often determined by difference, but it is advisable to check it by a more direct method. For this pur pose a fresh sample of the gas is circulated through a silica tube filled with copper oxide heated to bright redness, and is passed into a pipette filled with caustic potash solution. The whole of the gases present with the exception of the nitrogen are burned to carbon dioxide and water, both of which are absorbed in the potash. The operations are continued until the volume of the residual gas is constant, and a correction is applied for the air originally contained in the silica tube.

The Hempel apparatus is not portable, but a modification known as the Orsat apparatus (fig. 4) is portable. This resembles the Hempel in principle and use except that the pipettes are perma nently attached to the burette by a glass capillary tube and taps. When the apparatus is intended for the analysis of flue gases only, three pipettes are provided filled with caustic potash, alkaline pyro gallate and cuprous chloride, respectively. A bromine pipette and a palladium-asbestos tube are sometimes added. The carbon monoxide found will always be too low as only one pipette is employed for the cuprous chloride.

It has been assumed up to the present that the gases analysed are completely insoluble in water ; and with the exception of car bon dioxide, which is appreciably soluble, the assumption is cor rect enough for ordinary purposes. To avoid loss of carbon dioxide, the water is of ten saturated with the gas to be analysed ; or for more accurate work the water is replaced by mercury. The Sodeau apparatus is based on the same principle as the Hempel arrangement but employs mercury.

In the methods so far described the volume of the gas has been measured at a constant pressure and temperature. The alternative principle of measuring the gas at a constant volume and tempera ture can be equally well employed. This method has the advantage that 5 or io cu.cm. of gas can be expanded to give a pressure of r oomm. and that all the measurements are independent of the barometric pressure.

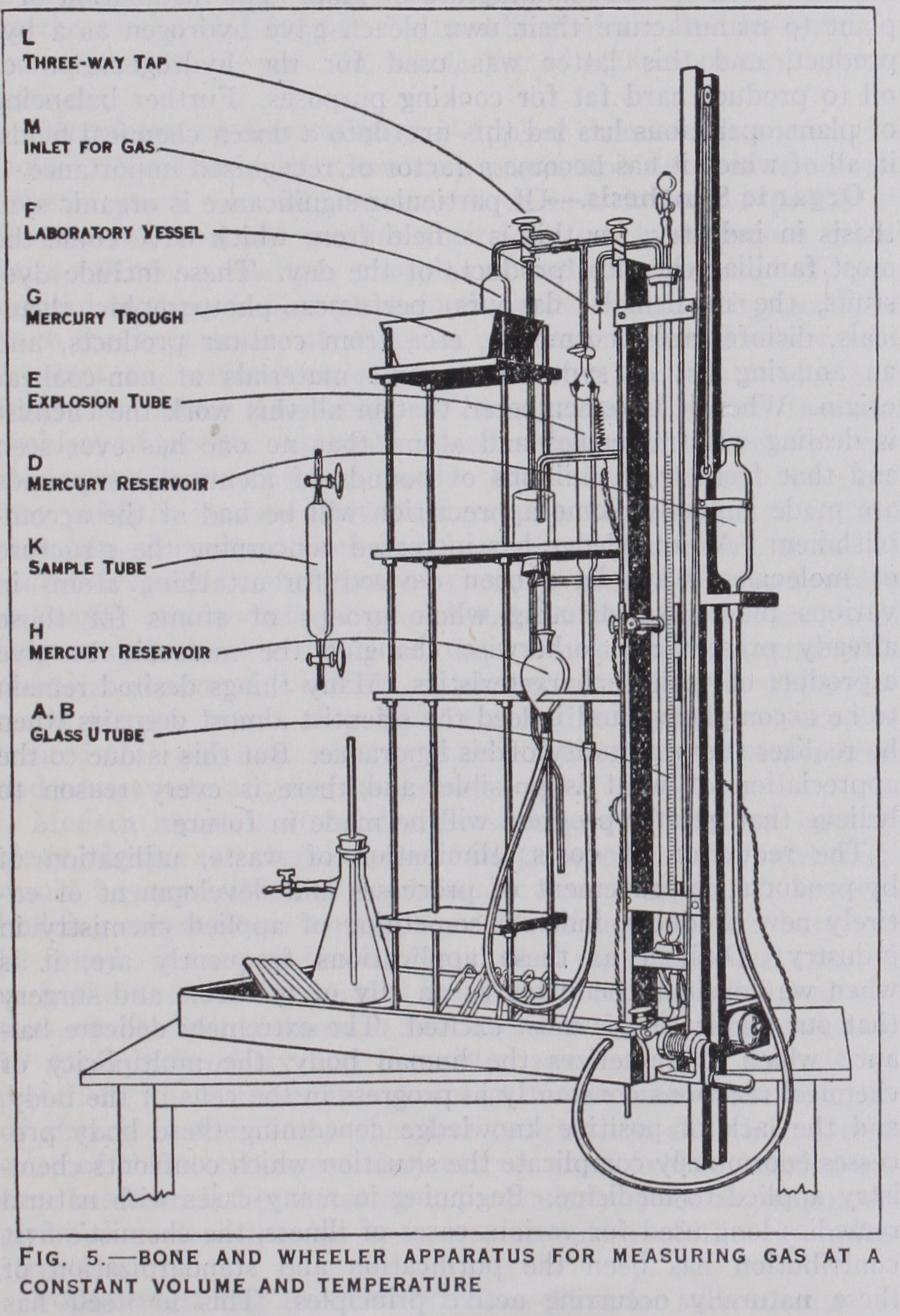

The Bone and Wheeler Apparatus.

This is the principle of the well-known Bone and Wheeler instrument which, as shown in fig. 5, consists of a glass U-tube AB connected at the bottom by thick-walled rubber tubing to the mercury reservoir D, the latter being raised and lowered by the winch. The U-tube is surrounded by a waterjacket through which water at a constant temperature is circulated. The limb B is graduated in mm., the limb A is marked by a series of constant-volume marks, each coinciding with a i oomm. mark on the pressure limb B (i.e., with o, zoo, 200mm., etc.). B is closed at the top with a glass cock, attached with rubber tubing and wired on. A is connected by capillary tub ing through various glass taps to the explosion tube E and the laboratory vessel F, which is open at the bottom and sealed with mercury in the trough G. The tap L also affords a passage to the waste bottle, which in turn is connected to a water-pump so that the contents of F can be removed from the apparatus. The explo sion tube E is fitted with platinum sparking points at the top end and is provided with a separate mercury reservoir. The whole apparatus is first filled with mercury and all the taps closed ; both tubes A and B are moistened with dilute sulphuric acid to ensure both being saturated with moisture and to avoid fouling with alka line solutions. Reservoir D is lowered and the lower tap opened so that a vacuum is produced in A and B. The lower tap is closed and the apparatus tested for tightness by seeing that the levels of the mercury in A and B remain the same, even when all the taps are opened back to the one closing the exit to the laboratory vessel F. Gas is then admitted either through M or under the mercury in F ; by raising or lowering D the level of the mercury is adjusted to one of the constant volume marks. The level of the mercury in B is then read and the difference between the levels of A and B will give the pressure of the gas in mm. of mercury. A few cu.cm. of the absorbent is placed in F, using a pipette with a curved tip for the purpose. The gas is then driven into F, gently agitated in contact with the absorbent until the removal of the constituent is complete, drawn back into A and the level of the mercury adjusted to the same constant level mark as at the start. The difference in the mercury levels now observed subtracted from the previous difference represents the amount of the gas absorbed, and the ratio of the two differences is the proportion of the constituent. The liquid in F is then drawn off to the waste bottle. All the operations are performed by rais ing or lowering D with the necessary manipulations of the taps. When necessary the absorbents are completely washed from F by 5% sulphuric acid. The hydrogen and methane are determined by explosion under reduced pressure with an excess of oxygen. The mixture in the tube A is passed into the explosion tube and fired by a spark. The subsequent operations are much the same as described in the Hempel method.

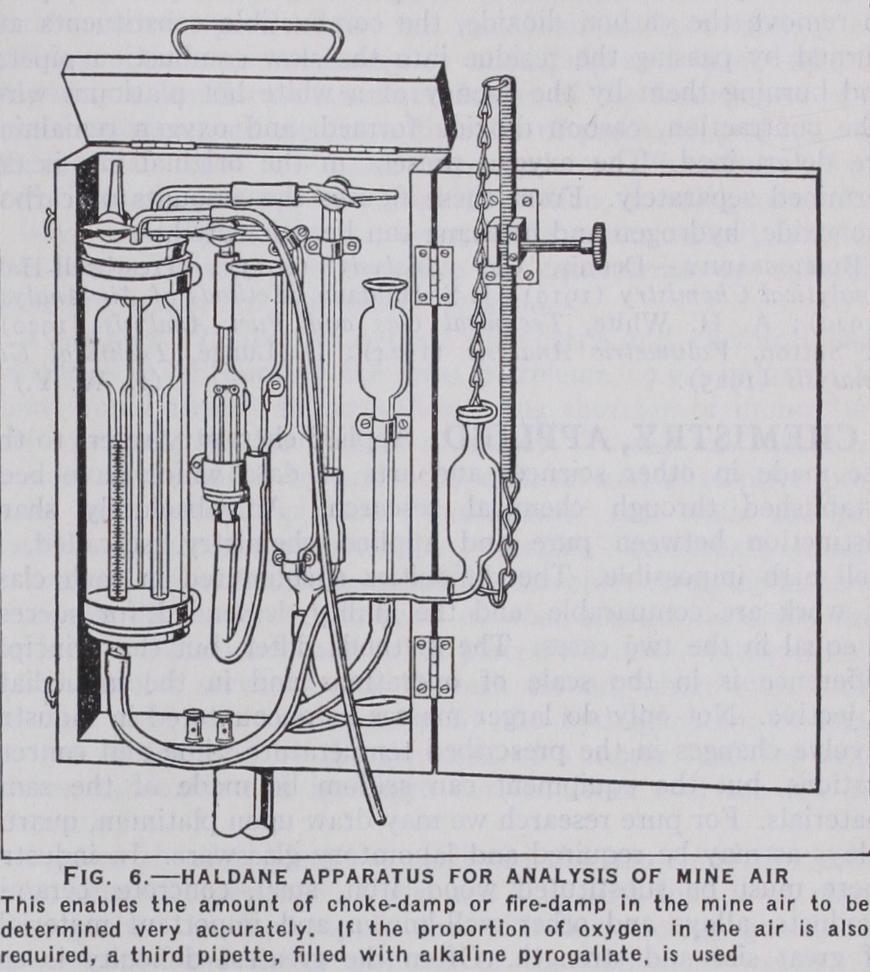

The Haldane Apparatus.

The portable form (fig. 6) is com monly employed for the analysis of mine air. This air in addition to oxygen and nitrogen may contain more carbon dioxide than is present in clean air, and may be contaminated with small amounts of carbon monoxide, hydrogen and methane. The determination of these constituents is of the utmost importance in connection with the safety of mines. Mercury is used as the confining liquid in a burette so constructed that small differences of volume can be accurately measured. This is attained by making the lower portion of the burette of much smaller diameter than the upper. The temperature and pressure of the gas are made to balance that of a constant mass of gas contained in a compensating tube. This tube is similar in shape and capacity to the burette and is placed at its side in the same water-jacket. Pipettes are provided for removing carbon dioxide and oxygen by potash and pyrogallate respectively. The mine air is first passed into the potash pipette to remove the carbon dioxide, the combustible constituents are burned by passing the residue into the slow combustion pipette and burning them by the agency of a white hot platinum wire. The contraction, carbon dioxide formed, and oxygen remaining are determined. The oxygen present in the original gas is de termined separately. From these figures the amounts of carbon monoxide, hydrogen and methane can be calculated.