Guages

GUAGES. The population of aboriginal America north of Mexico (about 1,15o,000), at the time of the discovery of America by Columbus, spoke an astonishing number of languages, most of which are still spoken, though in many cases by only a bare hand ful of individuals. Certain of them, like Sioux and Navaho, are still flourishing languages.

They consist of a number of distinct stocks, which differ fundamentally from each other in vocabulary, phonetics and grammatical form. Some of these' stocks, such as Algonkin, Siouan and Athabaskan, consist of a large number of distinct languages; others seem to be limited to a small number of languages or dialects or even to a single language. The so-called "Powell classification" of languages north of Mexico recognizes no less than S5 of these "stocks" (see the revised map of 1915 issued by the Bureau of American Ethnology), excluding Ara wak, a South American stock originally represented in the West Indies and perhaps also on the southwestern coast of Florida.

The distribution of these 55 stocks is uneven; 37 of them are either entirely or largely in territory draining into the Pacific, and 22 of these have a coast line on the Pacific. Only 7 linguis tic stocks had an Atlantic coast line. Besides the Pacific coast, in the lower Mississippi and Gulf coast, languages of 1 o stocks were spoken (apart from Arawak). The most widely distributed stocks are : Eskimoan, which includes Eskimo dialects ranging from east Greenland west to southern Alaska and East Cape, Siberia, as well as the Aleut of Alaska Peninsula and the Aleutian Islands; Algonkian, which embraces a large number of languages spoken along the Atlantic coast from eastern Quebec and Cape Breton Island south to the coast of North Carolina, in the in terior of Labrador, in the northern part of the drainage of the St. Lawrence, in the country of the three upper Great Lakes and the upper Mississippi, and west into the plains of the Saskatchewan and the upper Missouri; Iroquoian, which consists of languages originally spoken in three disconnected areas—the region of Lakes Erie and Ontario and the St. Lawrence, eastern Virginia and North Carolina, and the southern Alleghany country (Cherokee) ; Muskogian (including Natchez}, which occupies the Gulf region from the mouth of the Mississippi east into Florida and Georgia and north into Tennessee and Kentucky; Siouan, divided into four geographically distinct groups—an eastern group in Virginia and North and South Carolina, a small southern contingent (Biloxi) in southern Mississippi, the main group in the valley of the Missouri (eastern Montana and Saskatchewan southeast through Arkansas), and a colony of the main group (Winnebago) in the region of Green Bay, Wisconsin ; Caddoan, spoken in the southern Plains (from Nebraska south into Texas and Louisiana) and in an isolated enclave (Arikara) along the Missouri in North and South Dakota; Shoshonean, which occupies the greater part of the Great Basin area and contiguous territory in southern California and the southwestern Plains (Texas), also, disconnected from this vast stretch, three mesas in the Pueblo region of northern Arizona (Hopi) ; Athabaskan, divided into three geographically distinct groups of languages—Northern (the valleys of the Mackenzie and Yukon, from just short of Hudson's Bay west to Cook Inlet, Alaska, and from Great Bear Lake and the Mackenzie delta south to the headwaters of the Saskatchewan), Pacific (two disconnected areas, one in southwestern Oregon and northwestern California, the other a little south of this in California), and Southern (large parts of Arizona and New Mexico, with adjoining regions of Utah, Texas and Mexico)—besides isolated enclaves in southern British Columbia, Washington and northern Oregon; and *Salisli an, in southern British Columbia, most of Washington, and northern Idaho and Montana, with two isolated offshoots, one (Bella Coola) to the north on the British Columbia coast, the other (Tillamook) to the south in northwestern Oregon.

The remaining 46 stocks, according to Powell's classification, in alphabetical order, are : Atakapa (Gulf coast of Louisiana and Texas) ; Beot/ink (Newfoundland; extinct) ; Chimakuan (north western Washington) ; Chimariko (northwestern California) ; Chinook (lower Columbia river, in Washington and Oregon) ; Chitirnaclua (southern Louisiana) ; Chumash (southwestern Cali fornia) ; Coahuiltecan (lower Rio Grande, in Texas and Mexico) ; Coos (Oregon coast) ; Costanoan (western California south of San Francisco Bay) ; Esselen (southwestern California; extinct); Haida (Queen Charlotte Islands and part of southern Alaska) ; Kalapuya (northwestern Oregon) ; Karankawa (Texas coast) ; Karok (northwestern California) ; Keres (certain Rio Grande pueblos, New Mexico) ; Kiowa (southern Plains, in Kansas, Colo rado, Oklahoma, and Texas) ; Kootenay (upper Columbia river, in British Columbia and adjoining parts of Idaho and Montana) ; Lutuami, consisting of Klamath and Modoc (southern Oregon and northeastern California); Maidu (eastern part of Sacramento valley, California) ; Miwok (central California) ; Piman or Sono ran (southern Arizona and south into Mexico as far as the state of Jalisco) ; Porno (western California north of San Francisco Bay) ; Sahaptin (middle Columbia River valley, in Washington, Oregon and Idaho) ; Salinan (southwestern California) ; Shastan or Shasta-Achomawi (northern California and southern Oregon) ; Takelma (southwestern Oregon) ; Tanoan (certain pueblos in New Mexico, Arizona, and originally also in Chihuahua, Mexico) ; Timuqua (Florida; extinct) ; Tlingit (southern Alaska) ; Ton kawa (Texas) ; Tsimshian (western British Columbia) ; Tunica (Mississippi River, in Louisiana and Mississippi) ; Waiilatpuan, consisting of Molala and Cayuse (northern Oregon) ; Wakashan, consisting of Kwakiutl and Nootka (coast of British Columbia) ; Washo (western Nevada and eastern California) ; Wintun (north central California) ; Wiyot (northwestern California) ; Yakonan (Oregon coast) ; Yana (northern California) ; Yokuts (south central California) ; Yuchi (Savannah river, in Georgia and South Carolina) ; Yuki (western California) ; Yuman (lower Colorado River valley, in Arizona, southern California and south into all or most of lower California) ; Yurok (northwestern Cali fornia) ; Zuni (pueblo of New Mexico). To these was later added, as distinct from Yakonan, Siuslaw (Oregon Coast).

This complex classification of native languages in North Amer ica is very probably only a first approximation to the historic truth. There are clearly far-reaching resemblances in both struc ture and vocabulary among linguistic stocks classified by Powell as genetically distinct. Certain resemblances in vocabulary and phonetics are undoubtedly due to borrowing of one language from another, but the more deep-lying resemblances, such as can be demonstrated, for instance, for Shoshonean, Piman, and Nahuatl (Mexico) or for Athabaskan and Tlingit, must be due to a com mon origin now greatly obscured by the operation of phonetic laws, grammatical developments and losses, analogical disturb ances, and borrowing of elements from alien sources.

It is impossible to say at present what is the irreducible number of linguistic stocks that should be recognized for America north of Mexico, as scientific comparative work on these difficult languages is still in its infancy. The following reductions of linguistic stocks which have been proposed may be looked upon as either probable or very possible : i, Wiyot and Yurok, to which may have to be added Algonkian (of which Beothuk may be a very divergent member) ; 2, Iroquoian and Caddoan; 3, Uto Aztekan, consisting of Shoshonean, Piman and Nahuatl; 4, Atha baskan and Tlingit, with Haida as a more distant relative ; 5, Mosan, consisting of Salish, Chimakuan and Wakashan; 6, Ata kapa, Tunica and Chitimacha; 7, Coahuiltecan, Tonkawa and Karankawa; 8, Kiowa and Tanoan; 9, Takelma, Kalapuya and Coos-Siuslaw-Yakonan; io, Sahaptin, Waiilatpuan and Lutuami; I I, a large group known as Hokan, consisting of Karok, Chima riko, Shastan, Yana, Porno, Washo, Esselen, Yuman, Salinan, Chumash, and in Mexico, Seri and Chontal; 12, Penutian, con sisting of Miwok-Costanoan, Yokuts, Maidu and Wintun.

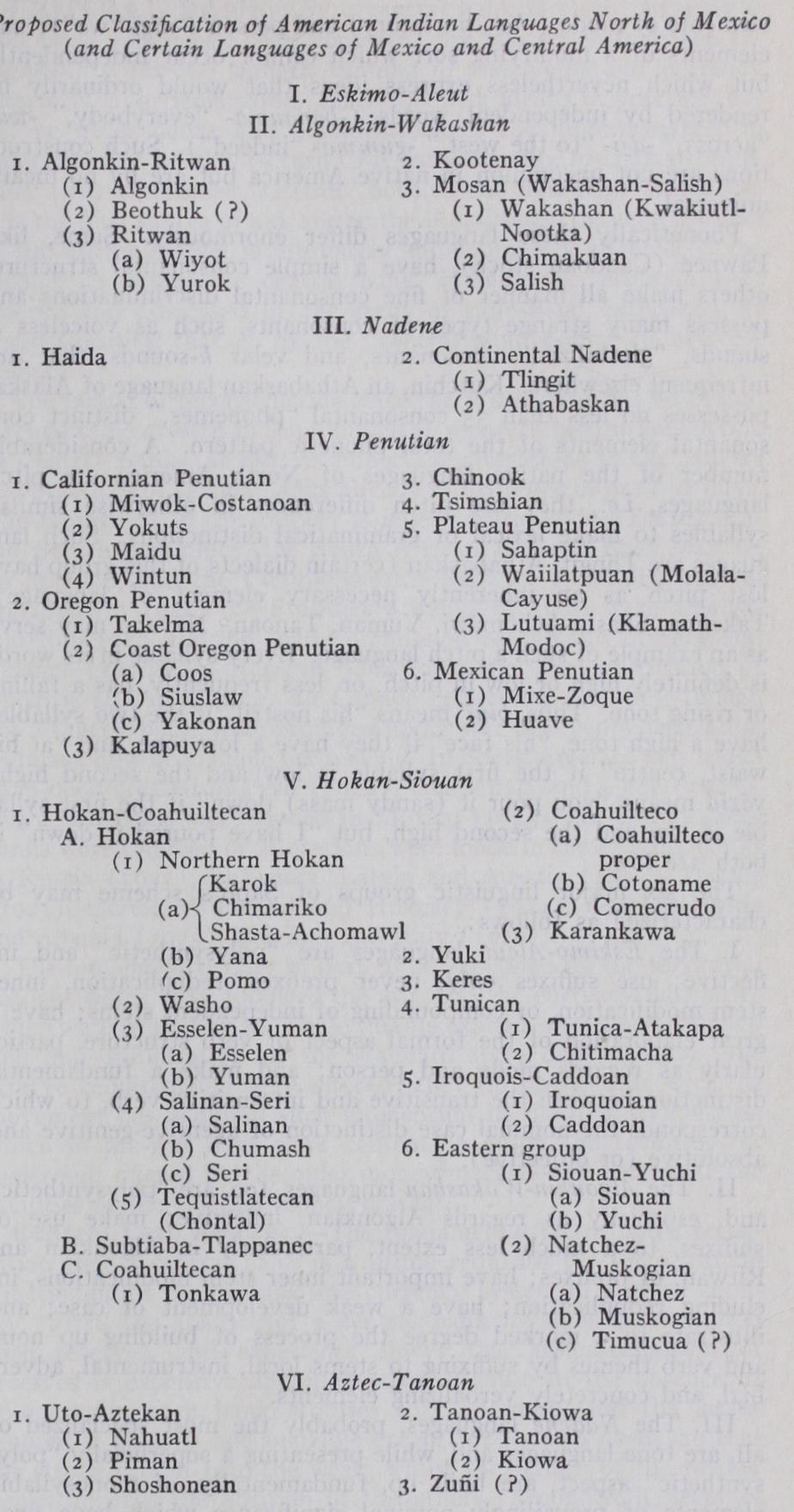

A more far-reaching scheme than Powell's, suggestive but not demonstrable in all its features at the present time, is Sapir's.

These linguistic classifications, shown in the next column, do not correspond at all closely to the racial or sub-racial lines that have been drawn for North America, nor to the culture areas into which the tribes have been grouped by ethnographers. Thus, the Athabaskan stock counts among its tribes repres entatives of four of the major culture areas of the continent : Plateau-Mackenzie area, southern outlier of West Coast area, Plains area and Southwestern area.

The aboriginal languages of North America differ from each other in both phonetic and morphological respects. Some are polysynthetic (or "holophrastic") in structure, such as Algon kian, Yana, Kwakiutl-Nootka, or Eskimo. Others, like Takelma and Yokuts, are of an inflective cast and may be compared, for structural outlines, to Latin or Greek; still others, like Coos, while inflective, have been reduced to the relatively analytic status of such a language as English ; agglutinative languages of moderate complexity, comparable to Turkish, are common, say Shoshonean or Sahaptin.

The term "polysynthetic" indicates that the language is far more than ordinarily synthetic in form, that the word embodies many more or less concrete notions that would in most languages be indicated by the grouping of independent words in the sentence. The Yana word yabanaumawild jigummaha'nigi "let us, each one (of us), move indeed to the west across (the creek) !" is "poly synthetic" in structure.. It consists of elements of three types— a nuclear element or "stem," yd- "several people move" ; formal elements of mode (-ha-, hortatory) and person (-nigi "we") ; and elements of a modifying sort which cannot occur independently but which nevertheless express ideas that would ordinarily be rendered by independent words (-banauma- "everybody," -wil "across," -dji- "to the west," -gumma- "indeed"). Such construc tions are not uncommon in native America but are by no means universal.

Phonetically these languages differ enormously. Some, like Pawnee (Caddoan stock), have a simple consonantal structure, others make all manner of fine consonantal discriminations and possess many strange types of consonants, such as voiceless 1 sounds, "glottalized" consonants, and velar k-sounds, that are infrequent elsewhere. Kutchin, an Athabaskan language of Alaska, possesses no less than 55 consonantal "phonemes," distinct con sonantal elements of the total phonetic pattern. A considerable number of the native languages of North America are pitch languages, i.e., they use pitch differences in otherwise similar syllables to make lexical or grammatical distinctions. Such lan guages are Tlingit, Athabaskan (certain dialects of this group have lost pitch as an inherently necessary element of language), Takelma, Shasta-Achomawi, Yuman, Tanoan. Navaho may serve as an example of such a pitch language. Every syllable in its words is definitely high or low in pitch, or, less frequently, has a falling or rising tone. Thus, bini' means "his nostril" if the two syllables have a high tone, "his face" if they have a low tone, and "at his waist, centre" if the first syllable is low and the second high; ydzid means "you pour it (sandy mass) down" if the first sylla ble is low and the second high, but "I have poured it down" if both are low.

The six major linguistic groups of Sapir's scheme may be characterized as follows : I. The Eskimo-Aleut languages are "polysynthetic" and in flective; use suffixes only, never prefixes, reduplication, inner stem modification, or compounding of independent stems; have a great elaboration of the formal aspect of verb structure, partic ularly as regards mode and person; and make a fundamental distinction between the transitive and intransitive verb, to which corresponds the nominal case distinction of agentive-genitive and absolutive (or objective).

II. The Algonkin-ll'akashan languages, too, are "polysynthetic" and, especially as regards Algonkian, inflective; make use of suffixes, to a much less extent, particularly in Algonkian and Ritwan, of prefixes; have important inner stem modifications, in cluding reduplication; have a weak development of case; and illustrate to a marked degree the process of building up noun and verb themes by suffixing to stems local, instrumental, adver bial, and concretely verbalizing elements.

III. The Nadene languages, probably the most specialized of Iii. The Nadene languages, probably the most specialized of all, are tone languages and, while presenting a superficially "poly synthetic" aspect, are built up, fundamentally, of monosyllabic elements of prevailingly nominal significance which have fixed order with reference to each other and combine into morpholog ically loose "words"; emphasize voice and "aspect" rather than tense ; make a fundamental distinction between active and static verb forms ; make abundant use of postpositions after both nouns and verb forms ; and compound nominal stems freely. The radical element of these languages is probably always nominal in force and the verb is typically a derivative of a nominal base, which need not be found as such.

IV. The Penutian languages are far less cumbersome in struc ture than the preceding three but are more tightly knit, present ing many analogies to the Indo-European languages; make use of suffixes of formal, rather than concrete, significance; show many types of inner stem change; and possess true nominal cases, for the most part. Chinook seems to have developed a secondary "polysynthetic" form on the basis of a broken down form of Penutian; while Tsimshian and Maidu have probably been con siderably influenced by contact with Mosan and with Shoshonean and Hokan respectively.

V. The Hokan-Siouan languages are prevailingly agglutinative; tend to use prefixes rather than suffixes for the more formal elements, particularly the pronominal elements of the verb; dis tinguish active and static verbs; and make free use of compound ing of stems and of nominal incorporation.

VI. The Aztec-Tanoan languages are moderately "polysyn thetic"; suffix many elements of formal significance; make a sharp formal distinction between noun and verb ; make free use of reduplication, compounding of stems and nominal incorporation; and possess many postpositions. Pronominal elements, in some cases nouns, have different forms for subject and object but the subject is not differentiated, as in types I. and IV., for intransitive and transitive constructions. (E. SA.) BIBLIOGRAPHY.-J. W. Powell, "Indian Linguistic Families of Bibliography.-J. W. Powell, "Indian Linguistic Families of America north of Mexico," Bureau of Ethnology, 7th Annual Report, pp. 1-142 (Washington, 1891) ; Franz Boas, "Handbook of American Indian Languages," Bureau of American Ethnology, Bull. 4o (pt. 1, 191I ; pt. 2, 1922) ; P. Rivet, "Langues de 1'Amerique du Nord," pp. 607-628 of A. Meillet et M. Cohen, "Les Langues du Monde (Paris, 1924)• Mexican and Central American Languages.—The classi fication of the native languages of Middle America is not in quite so advanced a stage as is that of the many languages spoken north of Mexico. The languages are, some of them, spoken by large populations, numbering millions, as in the case of Nahuatl (or Mexican) and the Maya of Yucatan; others are confined to very small groups, like the Subtiaba-Tlappanec of Nicaragua and Guerrero, or are extinct, as is Waicuri in Lower California. Nahuatl, Maya (with Quiche, Kekchi, and Cakchiquel, which belong to the Mayan stock), and Zapotec were great culture languages which had developed ideographic methods of writing.

The languages of Middle America may be conveniently grouped into three main sets : A., southern outliers of stocks located chiefly north of Mexico; B., stocks spoken only in Mexico and Central America, so far as is known at present; C., northern outliers of South American stocks. It is quite probable that rela tionships will eventually be discovered between some of the languages of group B and languages lying further north.

To group A belong three distinct stocks :

Uto-Aztekan, with two subdivisions, Sonoran (or Piman), spoken in a large number of dialects in northern Mexico, and Nahuatl (or Aztek), spoken in central Mexico and in a number of isolated southern enclaves —the Pacific coast of Oaxaca (Pochutla), three disconnected areas in Salvador and Guatemala (Pipil), two areas in Nicaragua and one in Costa Rica (Nicarao), and the Chiriqui region of Costa Rica (Sigua), of which dialects Nicarao and Sigua are now extinct—with Cuitlateco of Michoacan as a doubtful mem ber of the stock; Hokan-Coahuiltecan, represented by Hokan proper, which includes Seri (coast of Sonora), Yuman (in Lower California), and Tequistlateco or Chontal (coast of Oaxaca), by Coahuiltecan (Pakawan), of the lower Rio Grande, and by Subtiaba-Tlappanec, which is spoken in two small areas in Guerrero, one in Salvador, and one in Nicaragua; and Athabas kan (Apache tribes of Chihuahua and Coahuila).The Middle American languages proper (group B) may, with reservations, be classified into 15 linguistic stocks, which in alphabetic order, are : Chinantec (Oaxaca and western Vera Cruz) ; Janambre (Tamaulipas; extinct) ; Jicaque (northern Honduras) ; Lenca (Honduras and Salvador) ; Mayan (Yucatan and neighboring states of southern Mexico, British Honduras, western Honduras, and Guatemala), with an aberrant dialect group, Huastec, in the northeastern coast region of Mexico (Vera Cruz, San Luis Potosi, Tamaulipas) ; Miskito-Sumo Matagalpa, consisting of three distinct language groups : Miskito (coast of Nicaragua and Honduras), Sumo-Ulua (eastern Nica ragua and southern Honduras), and Matagalpa (Nicaragua ; a small enclave, Cacaope'ra, in Salvador) ; Mixe-Zoque-Huave, spoken in four disconnected groups, Mixe-Zoque (Oaxaca, Vera Cruz, Chiapas, and Tabasco), Tapachultec (southeastern Chiapas; extinct), Aguacatec (Guatemala, extinct), and Huave (coast of Mixtec-Zapotec, a group of languages that some con sider as composed of four independent stocks : Mixtec (Guerrero, Puebla, and western Oaxaca), Amusgo (Guerrero and Oaxaca), Zapotec (Oaxaca), and Cuicatec (northern Oaxaca) ; Olive (Tam aulipas; extinct) ; Otomian, consisting of three distinct groups: Otomi (large part of central Mexico), Mazatec (Guerrero, Puebla,- Oaxaca ; includes Trique and Chocho), and the geo graphically distant C/iiapanec-Mangue (Chiapanec in Chiapas; Mangue and related languages in three disconnected areas in Nicaragua and Costa Rica) ; Paya (Honduras) ; Tarascan (Michoacan) ; Totonac (Hidalgo, Puebla, and coast of Vera Cruz) ; Wa'icuri (southern part of Lower California; extinct) ; Xinca (southeastern Guatemala).

The outliers from South America are two : Carib (coast of Honduras and British Honduras; transferred in post-Columbian times from the Antilles) ; Chibchan (Costa Rica and Panama). In the West Indies two South American stocks were represented, Carib and Arawak, the latter constituting an older stream which had overrun the Greater Antilles and penetrated into Florida.

As to the languages of group B, some connect Chinantec, Mixtec-Zapotec, and Otomian in one great linguistic stock, Mixtec-Zapotec-Otomi. Both Xinca and Lenca (also Paya and Jicaque?) may be remote southern outliers of the Penutian languages of North America. W aicuri may have been related to Yuman. It is by no means unlikely that such important Middle American stocks as Mayan, Totonac, and Tarascan may also belong to certain of the larger stock groupings that have been suggested for North America ; e.g., Maya may fit into the Hokan Siouan framework, Tarascan into Aztek-Tanoan.

Middle America, in spite of its special cultural position, is distinctly a part of the whole North American linguistic complex and is connected with North America by innumerable threads. On the other hand, there seems to be a much sharper line of linguistic division, distributionally speaking, between Middle and South America. This line is approximately at the boundary be tween Nicaragua and Costa Rica ; allowances being made for Nahuatl and Otomian enclaves in Costa Rica and for an Arawak colony in Florida, we may say that Costa Rica, Panama, and the West Indies belong linguistically to South America. The Chibchan, Arawak, and Carib stocks of the southern continent were obviously diffusing northward at the time of the Conquest, but evidence seems to indicate that for Mexico and Central America as a whole the ethnic and linguistic movement was from north to south. Middle America may be looked upon as a great pocket for the reception of a number of distinct southward-mov ing peoples and the linguistic evidence is sure to throw much light in the future on the ethnic and culture streams which traversed these regions.

Two linguistic groups seem to stand out as archaically Middle American : Miskito-Sumo-Matagalpa, in Central America, and Mixtec-Zapotec-Otomi, with its center of gravity in southern Mexico. The latter of these sent offshoots that reached as far south as Costa Rica. The Penutian languages, centered in Oregon and California, must early have extended far to the south, as they seem to be represented in Mexico and Central America by Mixe Zoque, Huave, Xinca, and Lenca. These southern offshoots are now cut from their northern cognate languages by a vast number of intrusive languages, e.g., Hokan and Aztek-Tanoan. The Mayan languages, apparently of Hokan-Siouan type, may have drifted south at about an equally early date. Presumably later than the Penutian and Mayan movements into Middle America is the Hokan-Coahuiltecan stream, represented by at least three distinct groups—Coahuiltecan (N.E. Mexico), Subtiaba-Tlap panec (Guerrero, Nicaragua), and a relatively late stream of Hokan languages proper (Yuman; Seri; and Chontal in Oaxaca) . Not too early must have been the Uto-Aztekan movement to the south, consisting of an advance guard of Nahuatl-speaking tribes, a rear guard of Sonoran-speaking tribes (Cora, Huichol, Tara humare, Tepehuane) . The Nahuatl language eventually pushed south as far as Costa Rica. Last of all, the Apache dialects of Chihuahua brought into Mexico the southernmost outpost of the Nadene group of languages, which extend north nearly to the Arctic. (E. SA.) BIBLIOGRAPHY.-C. Thomas and J. R. Swanton, "Indian Languages Bibliography.-C. Thomas and J. R. Swanton, "Indian Languages of Mexico and Central America and their Geographical Distribution," Bureau of American Ethnology, Bull. 44 (Washington, 191I) ; W. Lehmann, Zentral-Amerika, I. Theil, "Die Sprachen Zentral-Amerikas" (Berlin, 192o) ; P. Rivet, "Langues de l'Amerique Centrale," pp. 629 638 of A. Meillet et M. Cohen. Less Langues du Monde (Paris, 1924) .