Heterocyclic Division

HETEROCYCLIC DIVISION The subject of heterocyclic compounds, comprising as it does a large group of substances occurring in nature (alkaloids, antho cyans, uric acid, etc.), is one of fundamental importance not only from the chemist's point of view in particular, but from the more general aspect having as its object the correlation of physics and chemistry with animal and plant metabolism. The synthesis of an enormous number of heterocyclic compounds has been accom plished, and these are of importance : (a) because of their identity with or relation to natural products, (b) because of some theoreti cal significance as, for example, in showing the mechanism of a chemical reaction, and (c) because of some properties that make them valuable to humanity, such as drugs, dyes, etc.

Heterocyclic compounds are distinguished from homocyclic compounds in that they contain at least one atom other than carbon in the ring. Such atoms may be of a variety of elements, but in most cases are nitrogen, oxygen, sulphur or selenium.

Heterocyclic compounds, like the homocyclic, may also exist in the form of fused ring systems, either with homocyclic or with other heterocyclic nuclei. Moreover while the fusion of two ben zene nuclei results in naphthalene, the fusion of a benzene and a pyridine nucleus may result in either quinoline (q.v.) or isoquino line, and the fusion of two pyridine nuclei may result in several isomeric naphthyridines of which the 1:8-derivative has recently been synthesized.

Aromatic properties have not been observed in three-, four-, seven-, or eight-membered rings but are restricted to five- and six-membered nuclei. Until the discovery of cyclo-octatetrene by Richard Willstatter, it was generally assumed that the presence of a series of alternate single and double bonds in a ring resulted in mutual saturation, with the consequent appearance of the aromatic properties. On this theory various formulae were ascribed to the benzene ring which were equally applicable to hetero cyclic nuclei. Among the more recent developments the theory of the aromatic sextet of electrons has gained considerable favour. This theory does not attempt to account for the double bonds, but assumes that the union of two members of the ring requires only one pair of electrons, so that there is a pair of electrons unac counted for by each conventional double bond, making in all three pairs or a sextet. It is admitted that the reasons for the stability of this system are not clearly understood, but neverthe less the view is a convenient one and generally applicable to the entire class of compounds which exhibit the aromatic charac teristics. In cyclo-octatetrene the four double bonds contribute more than the required sextet of electrons and the substance behaves like an unsaturated aliphatic compound. The same is true of cyclobutadiene (except that there is a deficit of two electrons here), whereas in pyridine the conditions for the aromatic sextet are fulfilled. The extension of this hypothesis to the •y-pyrones, furanes and thiophens follows, since the oxygen atom in the former is no longer neutral but acquires basic prop erties, with consequent ability to form stable salts and hence to supply the needed two electrons for the aromatic sextet.

The heterocyclic compounds are conveniently classified in two distinctive groups : (1) Unsaturated systems which often display a high degree of stability and constitute a well characterized class exhibiting a close relationship to benzenoid types—generally re ferred to as aromatic in character. (2) Systems resulting from ring closure of aliphatic (straight-chain) compounds to which in their deportment they display a close analogy and into which they are in general convertible by comparatively mild treatment, e.g., by hydrolysis.

Unsaturated Heterocyclic Compounds.

Unsaturated het erocyclic compounds often exhibit the characteristics of aro matic types, i.e., they usually possess a high degree of stability toward heat, some of them readily withstanding a dull red heat ; they are difficult to oxidize, and when oxidation does take place it is generally attended by complete destruction of the ring ; further more, the action of the halogens seldom results in addition com pounds as final products (although these may be formed as in termediates), substitution of hydrogen occurring when reaction takes place at all; the action of nitric and sulphuric acids is characteristic and results in the production of nitro-compounds and sulphonic acids respectively; the action of anhydrous alu minium chloride and an acid-chloride (reaction of Friedel and Crafts) frequently results in the formation of ketones ; finally, such compounds are as a rule not easy to reduce, and when re duction occurs the products behave like aliphatic compounds.The application of the above-mentioned hypothesis to the pyr roles, isoxazoles, oxazoles, pyrazoles, glyoxalines, etc.. follows readily when certain empirical rules are observed. It is only neces sary (1) to attribute an electron pair to each double bond whether that be a C–C or a C–N union, and (2) to attribute an electron pair to any divalent element or group in the ring such as oxygen, sulphur, selenium, imino– (NH= ), etc.

To the six-membered nuclei the same rules are applicable. Six• membered heterocyclic compounds containing nitrogen may be considered as derived from benzene by substituting a nitrogen atom for a methine (—CH) group. No chemical reactions are known, however, whereby a nitrogen atom can be introduced into a benzene ring in this way.

Properties of Unsaturated Heterocyclic Compounds.—The ex tent to which unsaturated heterocyclic compounds exhibit the properties of benzene and its derivatives varies considerably ; thus naphthalene has lost, to some extent at least, the chemical prop erties of benzene, for example in being much easier to oxidize than the latter. Just as the introduction of substituents into benzene may so modify the chemical properties that the nucleus no longer responds to well-known reactions, so it is hardly to be expected that pyridine should nitrate in exactly the same way that benzene nitrates.

Five-membered Aromatic Nuclei

(1) .—Five-membered rings containing one hetero-atom naturally fall into two distinct groups: (i.) those containing nitrogen in the ring, and (ii.) those containing oxygen, sulphur or selenium. The members of the second group resemble each other very closely in the methods of their synthesis and in their chemical and physical properties.Pyrrole and Its Derivatives.—Pyrrole does not occur as such in nature. It is a constituent of bone-oil and is obtained in large quantity, particularly in America, from the products of the destructive distillation of waste leather. Synthetically, it is ob tainable (and this is true of its alkyl and aryl derivatives) by dis tilling succinimide (or substituted succinimides) with zinc dust, the latter acting as a reducing agent.

A rather remarkable reaction is the easy conversion of pyrrole into succindialdoxime by the action of hydroxylamine: The imino-group is acidic, in that the hydrogen is readily replace able by potassium with the formation of crystalline potassium pyrrole.

The compounds formed by the fusion of pyrrole with other nuclei occur to some extent in nature. Indole, together with skatole (0-methylindole), is found in the products of pancreatic fermentation of albumins and the two products are generally present in human faeces. Indole, though it possesses a very offen sive odour, is found in jasmine and other flowers, and when judiciously blended frequently becomes an important constituent of synthetic perfumes.

(the betaine of N-trimethyltryptophane) occurs in Erythrina Iiypaphorus.

Of the more complex pyrrole derivatives, carbazole, which oc curs in crude anthracene, deserves special mention, because it is the parent substance of a large number of closely related com pounds (e.g., dinaphthopyrrole) some of which have found applica tion in the manufacture of dyes. An interesting variant of the Fischer indole synthesis has been achieved by the use of cyclo hexanone phenylhydrazone which yields tetrahydrocarbazole. The latter on mild oxidation with mercuric acetate forms car bazole. The natural alkaloids, rutaecarpine, harmine and harmaline belong to this class.

Furane and Its Derivatives.—Furane, the parent substance of this group, was first obtained in 187o by distilling the barium salt of pyromucic acid. This reaction is analogous to the formation of benzene from benzoic acid. Pyromucic acid, like benzoic acid, may be brominated and nitrated.

Indole was first obtained by distilling indigotin (the chief con stituent of natural indigo) with zinc dust. Among other syn theses of indole derivatives, that due to Emil Fischer (1886) is of wide application. In this method the phenylhydrazones of ketones, aldehydes or ketonic acids are heated with an acid (hydrochloric) or zinc chloride, when ammonia is eliminated.

The occurrence of tryptophane as a hydrolytic product of proteins deserves mention, whilst the closely related alkaloid, hypaphotrine Furfural, an important furane derivative both theoretically and commercially (being used in the manufacture of synthetic resins), is produced quantitatively when pentoses, like arabinose, are dis tilled with dilute acids. In its commercial manufacture, corn cobs, after the removal of grain, are distilled with dilute acid, and the aldehyde is found in the distillate. The methyl-pentoses (rhamnose, fucose, etc.) under similar treatment yield methyl f urf Ural. Furfural manifests all the reactions of aromatic alde hydes (e.g., benzaldehyde), and this behaviour follows necessarily from the aromatic nature of the furane ring. On treatment with caustic potash it yields pyromucic acid and furfuryl alcohol (Can nizzaro reaction) and on treatment in alcoholic solution with potassium cyanide it yields furoin (benzoin transformation). Coumarone and diphenylene oxide are representatives of con densed nuclei containing the furane ring.

Tliioplien and Its Derivatives.—Thiophen, a close analogue of furane, exhibits the greatest similarity to benzene. The four hydrogen atoms are replaceable by other groups, thus yielding innumerable derivatives, all of which give an intense blue colora tion—the indophenin reaction—when mixed with a little isatin and concentrated sulphuric acid. This reaction is given by all commercial samples of benzene, toluene, xylene, etc., and is due to small amounts of thiophen or the methylthiophens which are invariably present. Just as succinic acid (or its imide) may be transformed into pyrrole, so the distillation of a mixture of sodium succinate and phosphorus trisulphide yields considerable quan tities of thiophen. Of the fused nuclei, thiophthen, benzothiophen and diphenylene sulphide may be mentioned. Selenophen, the selenium analogue of thiophen, is less well known, but has been definitely characterized by H. V. A. Briscoe and J. B. Peel (1928) .

Five-membered Aromatic Nuclei

(2) .—There is a second series of five-membered heterocyclic compounds containing at least two hetero-atoms, which exhibit very marked aromatic properties. These compounds may he viewed as being derived from the foregoing five-membered heterocyclic compounds by the substitution of nitrogen atoms for methine (=CH) groups, and are collectively known as the azoles. Their names are derived from that of the parent monoheterocyclic nucleus and from the number of nitrogen atoms introduced. Thus furane and pyrrole each yield two isomeric azoles which are called furazoles and pyrazoles respectively. Substitution of two methine groups results in furo-diazoles and pyrro-diazoles. Similarly there are thiazoles, thio-diazoles, thio-triazoles, etc. In general, the azoles are some what resistant to oxidation, and when they are fused with the benzene ring it is often the latter which undergoes oxidation first. Thus, oxidation of benziminazole with potassium permanganate gives in part glyoxalinedicarboxylic acid. Further the C-alkyl derivatives (derivatives formed by replacing a hydrogen atom joined to carbon by an alkyl group) are frequently oxidized to carboxylic acids (3-methylpyrazole gives pyrazole-3-carboxylic acid) . It frequently happens that the azoles are only known in the form of fused systems (generally with benzene) or in the form of reduced derivatives.Pyrazoles.—The most convincing evidence of the aromatic nature of the pyrazole nucleus is the behaviour toward sulphuric and nitric acids, sulphonic acids and nitro-pyrazoles being formed respectively. The nitro-compounds are easily reduced to amino pyrazoles which on treatment with nitrous acid yield remarkably stable diazonium salts. The latter resemble the benzenediazonium salts in their transformations, and may, for instance, be converted into azo dyes by treating them with anilines, phenols, etc. The fusion of a pyrazole and a benzene nucleus results in the so-called indazole. There is no single expression which serves to account for the various transformations of indazole, and at least three different formulae have been suggested at various times. It is convenient to assume that the different forms are mutually con vertible into one another and that the environment or the mode of synthesis determines the type. The elusive character of the double bond makes it all the more explicable that indazole is strongly aromatic in properties, and on the basis of the electron sextet theory there is every reason to believe that the hydrogen atoms are in a state of dynamic equilibrium, and the system only becomes fixed when the hydrogen atoms are replaced. The fact that amino-indazole forms a comparatively stable diazonium salt is in complete agreement with the aromatic nature of the nucleus.

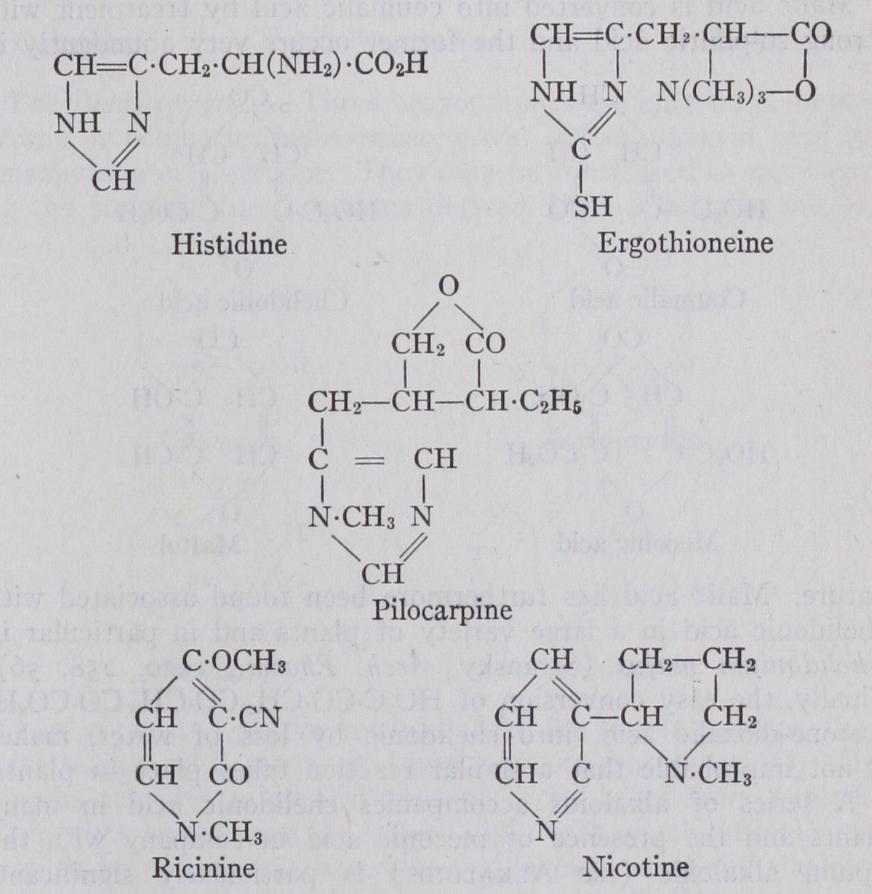

Glyoxalines.—Glyoxaline was discovered by Debus in 1856 as a reaction product of ammonia and glyoxal. Since then a large number of derivatives has been prepared and the chemistry of the entire class has been exhaustively studied by F. L. Pyman and his collaborators. The derivatives of glyoxaline which have been found in nature are perhaps limited to histidine, a product of the hydrolytic fission of many proteins ; ergothioneine, found in ergot and blood; and a series of alkaloids (e.g., pilocarpine) which occur in various species of Pilocarpus. The alkaloids are closely related to one another and differ only as regards the nature of the second ring.

Six-membered Heterocyclic Compounds

(1) .—The mem bers of this class which contain only one hetero-atom are by far the most important, and of these the nitrogen derivatives deserve special mention. The latter are, for the sake of convenience, divided into (1) derivatives of pyridine, and (2) fused systems containing the pyridine nucleus.The Pyridines.—Pyridine was discovered in 1851, and together with its homologues it occurs in bone-oil and coal-tar. Its properties and those of its derivatives are described in a special article (see PYRIDINE). The occurrence of pyridine derivatives, which do not contain other systems fused with the pyridine nucleus, is restricted to a relatively small number. Ricinine, occurring in the seeds of the castor-oil plant (Ricinus communis) is a derivative of a-pyridone ; its constitution has been ascer tained by its synthesis by Spath and Koller (1923) . Another important pyridine derivative is nicotine (see ALKALOIDS).

The Pyrones.—The pyrones are six-membered cyclic compounds containing an oxygen atom in the ring, together with a carbonyl (=CO) group. There are two forms theoretically possible, the a-pyrones and the y -pyrones.

In general, the pyrones have lost their aromatic characteristics to some extent, but are conveniently classified in this section. They are weak bases and the salts are readily hydrolysed by water. Though the pyrones contain a ketonic group, they do not react with the reagents (hydroxylamine, phenylhydrazine, etc.) which are used to characterize ketones and aldehydes. The halogens do not add themselves to the double bond but form substitution products. The action of ammonia, especially on pyronecarboxylic acids is noteworthy, for the oxygen atom is in many cases easily substituted with the formation of pyridones. In this way phenyl coumalin (present in coto bark) even with ammonium acetate gives a-phenylpyridone. This reaction throws some light on to the mechanism by which plants may arrive at a synthesis of cyclic nitrogen compounds. The pyrones are easily formed from certain aliphatic compounds which might occur in nature as intermediates, and the subsequent transformation of the pyrones into pyridine and fused pyridine derivatives is entirely within the bounds of possibility.

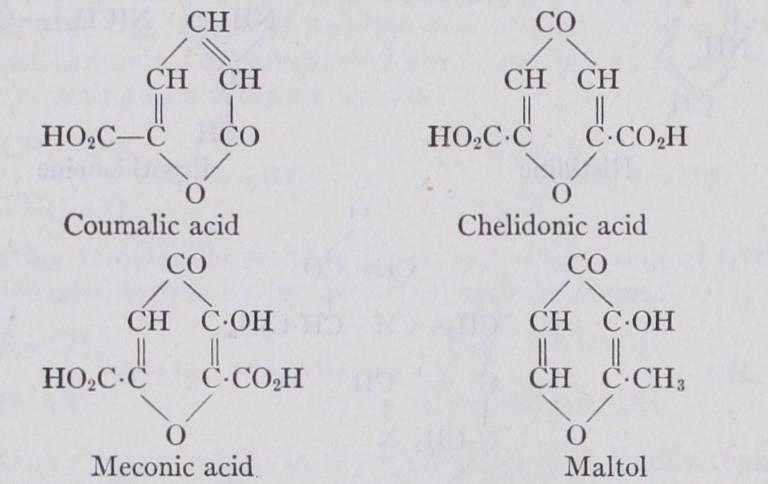

Malic acid is converted into coumalic acid by treatment with strong sulphuric acid and the former occurs very abundantly in nature. Malic acid has furthermore been found associated with chelidonic acid in a large variety of plants and in particular in Clcelidonium majus (Stransky, Arch. Pharm., 1920, 258, 56). Finally, the easy conversion of acetone-dioxalic acid, into chelidonic by loss of water, makes it not improbable that a similar reaction takes place in plants.

A series of alkaloids accompanies chelidonic acid in many plants and the presence of meconic acid in company with the opium alkaloids (see ALKALOIDS) is particularly significant. Ammonia and perhaps other bases are admittedly present in all plants at some stages of growth, and this, together with the pyrones, which are particularly abundant in some plants that elaborate alkaloids, may supply the needed starting products for the vital synthesis of pyridine bases. a-methyl-O-hydroxy-y pyrone (or maltol) occurs in the needles of pines and the bark of larches, and is also formed on roasting malt.

Six-membered Heterocyclic Compounds (

2) : Fused Nuclei.—The fused ring systems containing a heterocyclic nucleus are particularly abundant in nature. They are in many cases more readily accessible by synthetic means than those containing only one ring. This is accounted for by the fact that they are largely derived from ortho-disubstituted benzenes. The latter are avail able by a great diversity of methods. In many instances, too, it is possible to bring about a ring closure (in the ortho-position) of a benzene derivative having a suitable side chain. For example, aniline reacts with ethyl acetoacetate, CH;{•CO•CH.,•CO•C.,H,, form ing first ethyl /3-anilino-crotonate (I) which on treatment with sulphuric acid gives a -methyl-y-hydroxyquinoline (2) and al cohol, thus: Quinoline and Its Derivatives.—Quinoline occurs in bone-oil and coal-tar and results when any of a large number of alkaloids is distilled alone or with zinc dust. Its synthesis and properties, together with those of its simple derivatives, are described in the article QUINOLINE. In their synthesis of cusparine, Spath and Brunner (1924) condensed y-methoxyquinaldine with piperonal, and the resulting piperonylidene derivative (I) was reduced catalytically with hydrogen in the presence of palladium yielding a product identical with cusparine (2), obtained from the natural source (the bark of Galipea cusparia). The alkaloid galipine (3), which accompanies cusparine in Galipea cusparia, was synthesized by a similar series of reactions, except that veratraldehyde was substituted for piperonal in the condensation.

An interesting synthesis of /3-chloroquinaldine is achieved by treating a mixture of a-methylindole with chloroform and sodium ethylate.

This reaction is applicable to pyrroles and indoles in general and results in pyridines and quinolines respectively. When methylene iodide is used instead of chloroform in this reaction the products are pyridines and quinolines free from halogen. Kynurenic acid is of importance because of its occurrence in the urine of dogs after the ingestion of meat. It is also formed in the transposition of tryptophane and has been prepared synthetically. When it is heated, it loses carbon dioxide and is converted into kynurine or -y-hydroxy-quinoline. Cinchoninic and quininic acids are men tioned because of their relation to cinchonine and quinine respectively.

Among the synthetic quinoline derivatives, a-phenyl-cincho ninic acid deserves mention on account of its general use as an antineuralgic and as a remedy for gout. It is known in commerce under the name of atophane, and has been specially recommended in the form of its hydriodide. A large number of derivatives of atophane have been prepared with a view to improving its' value as a drug. The chemistry of the alkaloids of Cinchona forms one of the most inspiring chapters of historical chemistry. It was in 1 792 that Fourcroy first isolated quinine in an impure condition. In 181o, Dr. Gomes, a Spanish physician, obtained a crystalline substance which he called "Cinchonino" from cinchona bark. The basic properties of this material were brought to the notice of Pelletier and Caventou, who, inspired by the recent observation of Serturner on the existence of "organic alkalies" in nature, un dertook an investigation of "cinchonino" and succeeded it isolat ing two substances which they named quinine and cinchonine. Later, they isolated strychnine and brucine from the seeds of nux vornica. The chemistry of strychnine has formed the subject of almost incessant research since its discovery. Over Ioo years have elapsed and although it contains only 21 carbon atoms in the molecule, its constitution is still in doubt, although some evidence points to the existence of a partly reduced quinoline nucleus.

More than 20 alkaloids have been isolated from the various species of cinchona and Remijia (natural order, Rubiaceae) but only cinchonine and especially quinine have found an extensive application in medicine. The antipyretic properties of cinchona bark have been suspected in Europe since 1639, but the drug did not come into general use until nearly thirty years later. Although neither cinchonine nor quinine has been synthesized, the painstaking work of Hesse, of Rabe, of Konigs and their collaborators has left no room for doubt regarding the constitution of either base, together with that of a large number of associated alkaloids.

separated from the benzene nucleus by a methine group : the difference is shown by their formulae : Isoquinoline occurs to some extent in coal-tar, and is produced in the destructive distillation of certain alkaloids. Its properties are described in the article QUINOLINE. The occurrence of iso quinoline derivatives in nature is restricted (except in one well defined case—that of papaverine) to systems containing the pyri dine ring partly or wholly reduced. The alkaloids of Anlialoniurn, Hydrastis, Berberis, Corydalis, Chelidonium, opium, etc., belong in this group. They exist in a wide variety of types and special works must be consulted for details (see ALKALOIDS).

The Benzopyrones.—Three benzopyrones are known : a-benzo pyrone or coumarin, iso-a-benzopyrone or isocoumarin, and y benzopyrone or chromone. They may be considered as represent ing the simplest fused systems derived from a benzene nucleus Large numbers of more complex quinolines have also been pre pared. These are of the nature of fused systems containing quinoline condensed with benzene and pyridine nuclei. Acridine, phenanthridine and anthrapyridine represent quinolines fused with a benzene nucleus.

and an a- or a y-pyrone nucleus. Like the simple pyrones, they react readily with ammonia (especially the isocoumarins). The remarks relative to the synthesis of cyclic bases from pyrones, made when considering the latter, apply with equal consequences here. It is not at all uncommon to find benzopyrones and alkaloids in the same plant. The delphiniums contain alkaloids in abund ance, and kaempferol and related flavonols have been isolated from a number of them. Many flavonols are dealt with in the article ANTHOCYANINS.

The two glucosides, aesculin and daphnin, on mild hydrolysis yield glucose together with aesculetin and daphnetin respectively.

The melting-points of the condensed systems gradually rise as more nuclei are added. There appears to be no upper limit to the number of nuclei that can be condensed into one system. The products, however, become more difficult to work with on account of their sparing solubility and high melting-points.

Isoquinoline and Its Derivatives.—Structurally, isoquinoline differs from quinoline in the position that the nitrogen atom takes up in the hetero-ring. In the former the nitrogen member is Umbelliferone occurs in the bark of Daphne mezereum and is ob tained by distilling different resins, such as galbanum and asafoet ida. No derivative of isocoumarin has been isolated from natural products.

The Dibenzo-y-pyrones.—The simplest dibenzo-y-pyrone, xan thone, is obtained synthetically by a number of methods. The majority of naturally occurring yellow colouring matters are rived from the latter or from flavone, although xanthone has not been found in plants. Only two members of the xanthone group have been isolated from natural products.

Euxanthic acid is the chief organic constituent of Indian yellow or purree. The latter used to be made in Bengal from the urine of cows which had been fed on mango leaves, but the crude prod uct had a disagreeable odour and is now replaced almost entirely by synthetic dyestuffs. When heated with dilute acids, euxanthic acid is decomposed into glycuronic acid, and euxanthone. It is interesting to note that when euxanthone is administered to dogs and to rabbits it is eliminated in the urine in the form of its combination with glucuronic acid, that is as euxanthic acid. Gentisin, the colouring matter of gentian root, is a methoxy euxanthone.

Reduction of xanthone converts it by stages into xanthydrol and xanthene. The former contains the nucleus of a number of syn thetic dyes and indicators. Conspicuous amongst these is fluor escein, the substance obtained by heating a mixture of phthalic anhydride, resorcinol and zinc chloride. Fluorescein and allied products are characterized by the fact that on treatment with Six-membered Polyhetero-atomic Nuclei (I ) .—The six membered nuclei containing two or more hetero-atoms may be regarded as derived from the six-membered nuclei containing one hetero-atom by substituting one or more methine (=CH) groups by nitrogen atoms. No strictly aromatic nuclei containing other atoms than nitrogen are known to occur, although theoretically ring systems containing quadrivalent oxygen are possible. These would be analogous to the pyrans, but are only known in the re duced form corresponding to the dihydro- and tetrahydro-pyrans. The entire group is known as azines and the members are termed diazines, oxazines and thiazines, according to whether they are de rived from pyridine, by the replacement of a methine group by ni trogen, by oxygen or by sulphur, respectively. Only those members which contain nitrogen atoms in the ring are of much importance. A few of these occur in nature and some are used as dyes. It may be mentioned, however, that some complex and valuable dyes are derived from systems containing sulphur in the ring. Morpholine (so called because it was at one time thought that a similar ring was present in morphine), phenoxazin, thiodiphenylamine, and dioxane may be mentioned as examples of a class of substances which contain six-membered rings with only one or no nitrogen atom.

alkalis they yield coloured salts, displaying an intense fluorescence, which is attributed to the formation of the quinonoid form, stable only in alkaline media. Phthalic anhydride may be replaced by other anhydrides, and resorcinol by other phenols. The product from succinic anhydride and resorcinol is termed succinein. The latter, and particularly the phenyl-succineins, also display a series of colour changes, together with a fluorescence, dependent on the alkalinity of the medium.

Dihydro-pyran Group.—Though the dihydro-pyrans do not be long to the aromatic heterocyclic compounds, they are con veniently mentioned because of their close relation to the pyrans.

A

history which treats of natural dyes would undoubtedly de vote considerable space to those chapters dealing with logwood (q.v.), Brazilwood (q.v.), Pernambuco and Sappanwood (see BRAZILwooD). The Brazilwood is the product of Caesalpinia braziliensis. The use of logwood dyes, the product of Caesalpinia echinata, was prohibited in England by act of parliament in the reign of Queen Elizabeth, because it was said to produce fugitive colours. The names of W. H. Perkin, Jr., and R. Robinson are in timately associated with the chemistry of Brazilwood and logwood, which contain respectively brazilin and haematoxylin (C10111408).Reference has already been made to the diazines in connection with the general characteristics of aromatic nuclei. They have been synthesized in some abundance, but the systems containing only one nucleus are not known to occur naturally.

Six-membered Polyhetero-atomic Nuclei ( 2) . Fused Sys tems.—The fusion of pyridazine with benzene may result in either cinnoline or phthalazine, depending upon the position of attach ment of the benzene nucleus.

The hetero-rings in these systems are very stable to oxidation. Phthalazine on treatment with alkaline potassium permanganate yields pyridazine-4 :5-dicarboxylic acid. Phthalylhydrazine is prob ably dihydroxy-phthalazine, the keto-form passing into the more stable enol-form (hydroxy-f orm) : Among the halogeno-cinnolines and phthalazines those containing the halogen attached to the hetero-nucleus display the same reac tions that are characteristic of a-and y-chloro-quinolines. The halogens are readily replaceable by hydroxyl, amino- and similar groups. The methyl groups in the methyl derivatives are char acterized by the same reactivity that they show in quinaldine and lepidine.

In the pyrimidine series there is only one benzo-derivative possi ble, namely, quinazoline. Oxidation converts it into pyrimidine 4 :5-dicarboxylic acid by rupture of the benzene nucleus. The others, the eurhodines, toluylene-red, the indulines, safranines, indazines, etc. (see DYES, SYNTHETIC). The indulines are among the longest known aniline dyestuffs, having been described in 1865 by Caro and Dale. Derivatives of the three theoretically possible triazines are known. Cyanuric chloride is probably trichloro cyandine, while cyanuric acid is the corresponding hydroxy-deriva extended labours of Marston T. Bogert have placed on record a truly formidable number of quinazolines. It is remarkable, how ever, that this list does not include either 2-n-propyl- or 2 isopropyl-4-hydroxyquinazoline, one of which is considered as rep resenting the constitution of vasicine, an alkaloid obtained by Ghose (1927), from Adhatoda vasica. This is the only quinazoline derivative so far isolated from natural products.

Attention may be directed to the natural occurrence of a group of reduced purine derivatives of which caffeine, which occurs in coffee and tea, represents a member. Purine (q.v.) is the name applied to the system f ormect by the fusion of a pyridazine and glyoxaline nucleus, and is of special interest because it is related to uric acid.

Quinoxaline is the only possible compound obtainable by fusion of a pyrazine and a benzene nucleus. Oxidation ruptures the ben zene nucleus and yields pyrazine-a:0-dicarboxylic acid. Quinoxa lines are particularly easy to synthesize from ortho-phenylene diamines on the one hand and I :2-diketonic compounds on the other. In many cases the reactions are complete even at low temperatures. The synthesis of quinoxaline from o-phenylene diamine (I) and glyoxal (2) is represented as follows : The more complex derivatives of pyrazine and particularly of phenazine form an extensive class of dyestuffs which are of some importance from the technical standpoint. These include, among tive. Many cyanides polymerize (see POLYMERIZATION) to deriva tives of cyanidines spontaneously or on treatment with sulphuric acid, etc. Some derivatives of a-triazine are known, but f3-triazine is only known in the form of reduced benzo-derivatives, e.g., benzazimide. Three tetrazines are theoretically possible, but only on account of its high content of nitrogen and because of its purple colour. It is quite stable and may be readily sublimed. Het erocyclic- systems containing more than four nitrogen atoms are unknown.

Aliphatic Heterocyclic Compounds.

The aliphatic hetero cyclic compounds are so closely related to the corresponding straight-chain members that they are conveniently divided into a number of classes, each class being derived from a corresponding type of aliphatic compound by the elimination of a molecule of water, ammonia, etc. On this basis the heterocyclic compounds are conveniently divided into the following groups : (I) cyclic ethers and thio-ethers of glycols and thio-glycols; (2) cyclic alky lene-amines resulting from diamino-paraffins by loss of ammonia or from chloro-amino-paraffins by loss of hydrogen chloride; (3 ) the lactones and lactides—internal ethers of hydroxy-acids (see Acms) ; (4) lactams and betaines (q.v.)—internal anhydrides of amino-acids; (5) cyclic derivatives of dicarboxylic acids (anhy drides, imides, hydrazides, alkylene-esters) ; (6) dihydro-pyrroles and tetrahydro-pyridines derived from amino-aldehydes and amino-ketones by loss of water. In many cases hydrolysis by means of acids and alkalis converts such cyclic compounds into the substances from which they are derived, but there are important exceptions.The ease with which heterocyclic compounds are formed varies largely with the number of atoms in the ring. In general three- and four-membered rings are difficult to prepare, and once prepared are easily ruptured. They often behave as unsaturated compounds with which they are isomeric. Compounds containing up to 16 atoms in the ring, including several hetero-atoms, have been reported, but in many cases considerable doubt exists as to the validity of the assigned formulae. It has been frequently observed that three, four, seven, eight and higher carbon rings are usually much more difficult to form than five- and six membered rings. In order to offer an explanation for this fact A. von Baeyer was led to announce his celebrated "Strain Theory," which has been discussed in the homocyclic section, and which applies almost equally to heterocyclic compounds. Thus, in gen eral, five-membered rings are the most stable, six-membered rings are nearly as stable, whilst seven- and four-membered rings are less so, and three-membered still less.

The Cyclic Ethers.—The ethylene oxides are the most impor tant members of this class. Two methods of preparation, both depending upon olefines for their starting materials, are important. In one case hypochlorous acid is added to the double bond and the resulting chlorohydrin is treated with alkali which removes hydrogen chloride : In the second method the olefine is treated with benzoyl peroxide, the function of which is to supply one oxygen atom: During the World War large quantities of ethylene chlorohydrin were used in the manufacture of mustard gas. It was then made by the combined action of moist chlorine on ethylene, the water and chlorine reacting potentially to give hypochlorous acid. On the cessation of hostilities, peace-time uses were sought for this product, and it was converted into ethylene oxide, which has found a number of technical applications, e.g., as a solvent.

The ether linkage is easily ruptured by a great diversity of rea gents. The hydrogen halides open the ring and the products are the halogenohydrins. Amines act similarly and the products are amino-ethanols, e.g., with ammonia, a-aminoethanol, is formed. Some amino-ethanols find extensive applica tion in the synthesis of local anaesthetics.

The action of Grignard reagents on ethylene oxide is a particu larly useful means of adding two carbon atoms to a chain. When n-butyl magnesium bromide, is treated with ethylene oxide, an addition compound is first formed, which on gentle heat ing changes to a product which yields n-hexyl alcohol on de composition with water. This reaction is applied commercially in the synthesis of 13-phenylethyl alcohol, which finds some application in perfumery. Trimethylene oxide, be appreciated. This system is present in haemoglobin, chlorophyll (q.v.) and haemocyanin, and all evidence points to the existence of a close relationship between these natural products. The chemist has, as it were, supplied proof of the kinship of plant and animal life. The present chemical evidence goes to show that the rings are present in their unsaturated state and therefore these vital products must be classified with the pyrroles. The existence of pyrrolidine derivatives in nature is not confined to a few repre sentatives. It is possible that some proteins may contain a pyrroli done system, because the glutamic acid formed in their hydrolysis easily passes into pyrrolidonecarboxylic acid.

Proline and 4-hydroxyproline are products of the hydrolysis of proteins. Stachydrine (found in Stachys tuberi f era) and betoni cine (found in Betonica officinalis) are the betaines of the dime thylammonium derivatives of proline and 4-hydroxyproline respec oxide, but the higher ring homologues behave like the chain ethers. Cineol, a constituent of eucalyptus oil, is a complex cyclic ether (see TERPENES) .

Cyclic Imines.—The methods available for the synthesis of cyclic imines are, in general, the same as those for preparing sec ondary aliphatic amines. Those members of this group containing three and four atoms in the ring are difficult to prepare and not well known. A three-membered ring consisting of two nitrogen atoms and one carbon atom is present in diazomethane (z ) and diazoacetic ester (2) . Diazomethane is extremely poisonous but is of considerable use as a methylating agent in neutral media.

tively. Hygrine, together with a group of related alkaloids, occurs in some varieties of coca leaves, and it is isomeric with tropine, as may be seen from the formulae. Physostigmine, the principal al kaloid of the Calabar bean (from Physostigma venenosum) is the only representative, either synthetic or natural, of a compound containing two pyrrolidine rings and a benzene nucleus.

Diazomethane and its derivatives have the remarkable property of adding themselves to olefine-carboxylic acids ; with ethyl fumarate it yields ethyl pyrazolidine-4 : 5-dicarboxylate (3) . The latter when heated loses nitrogen and passes into ethyl cyclopropane-i :2 dicarboxylate (4)• Closely related to the pyrazolines, which are dihydro-pyrazoles, are the pyrazolones, which comprise a group of drugs possessing antipyretic properties. The representative of this group which has found the greatest favour is antipyrine (q.v.) . Many reduced systems corresponding to and derived from the aromatic nuclei al ready discussed are known. Except for the five- and six-membered rings containing only one nitrogen atom they are relatively unim portant.

The Pyrrolidines.—The importance of the systems represented by a ring of one nitrogen and four carbon atoms can scarcely The Piperidines.—Nature appears to have a special predis position for the elaboration of piperidines, which are to be re garded as reduced pyridines. Piperine (q.v.), the chief constit uent of pepper, yields piperidine and piperic acid on heating with alkalis. Conversely, piperic acid chloride on treatment with piperidine yields piperine, showing that the latter is the piperidide of piperic acid. Considerable interest attaches to the chemistry Anhydrides and Imides.—Anhydrides of dibasic acids are readily formed when they contain either five or six atoms in the ring. A few seven-membered cyclic anhydrides are known and among these that of diphenic acid may be mentioned.

of coniine, a constituent of common hemlock (Corium macula turn) and the first alkaloid to be synthesized. The toxic proper ties of hemlock juice were recognized by the ancient Greeks, for it is recorded that Socrates was compelled to take an extract of hemlock in order to pay the supreme penalty exacted by the State.

The root bark of pomegranate, Punica granatum, contains a mixture of alkaloids from which five individuals have been iso lated. Pelletierine and three others are closely related to coniine. The fifth alkaloid, pseudo-pelletierine, is the best known of the group, and is closely related to the tropine alkaloids, which include cocaine, tropococaine, benzoyl-ecgonine, etc. This group of alkaloids is characterized by the fact that hydrolysis by alkali resolves them into two parts, one an acid and the other a hydroxyamino-compound. Atropic acid, (from hyoscyamine), benzoic acid and cinnamic acid are among the acid constituents. The basic groups are somewhat restricted to tropine and ecgonine, but others of less frequent occurrence are known. The alkaloids can be regenerated from their hydro lytic products and are theref ore to be regarded as esters of the acid in combination with the secondary hydroxyl group. Fre quently the carboxyl group is esterified; thus cocaine is methyl benzoyl-ecgonine.

The most important member of the cyclic imides is phthalimide, obtained by heating phthalic anhydride and ammonia. It forms a potassium derivative, which when heated with alkyl halides forms potassium halide and an alkyl-phthalimide, which on hydrol ysis with acids yields phthalic acid and the corresponding alkyl amine. This reaction is applicable to an infinite variety of alkyl halides and is due to the extended researches of Gabriel and his co-workers. The hydrolysis with acids is, however, difficult in some cases, and a recent communication has overcome this obstacle by the ingenious use of hydrazine hydrate, which, with an alkylphthalimide, yields the free amine and phthalylhydrazide. For example, benzylamine, is readily formed by treating benzylphthalimide with hydrazine hydrate. Benzyl phthalimide is obtained by heating potassium phthalimide with benzyl chloride, A number of heterocyclic compounds containing phosphorus, arsenic, antimony, bismuth, silicon, lead, mercury and tellurium in the ring have been prepared. They are frequently derived from the Grignard compounds of 1:4-dibromobutane or i :5-dibromo pentane. The latter on treatment with silicon tetrachloride or with the compound, yields the two products (I) and (2) respectively.

Closely related to piperidine is quinuclidine, which represents an unusual type of organic architecture present in the cinchona alkaloids. The synthesis of quinuclidine, which involved a con siderable number of stages, must be regarded as a noteworthy achievement. The alkaloid, sparteine, occurring in Cytisus scopa rius, is generally regarded as containing either one or two quinuclidine groups (see ALKALOIDS).

Lactams.—The lactams are cyclic amides of amino-acids, and are present in abundance in protein molecules. The synthesis of lactams from the oximes of cyclic ketones is interesting, and is a special case of the Beckmann transformation. Cyclopentanone oxime on treatment with strong sulphuric acid gives a-piperidone.