The Gaseous State

THE GASEOUS STATE General Characteristics.—Matter in the gaseous state is dis tinguished by its tendency to occupy all the space at its disposal. This tendency may be counteracted by external forces, and the fact that the earth's gaseous atmosphere is confined within definite limits is to be attributed to the circumstance that the gaseous molecules are under the influence of gravitational force. Gases are particularly susceptible to changes of pressure and of tem perature.

In 1662 Robert Boyle showed that the volume occupied by a gas varies inversely as the pressure when the temperature is constant. When kept at constant pressure, a gas expands when heated and the expansion or relative change in volume was found by Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac and John Dalton (1802) to be proportional to the rise in temperature. If v and are the vol umes occupied at t° C and o° C, the relation between the volumes is given by at in which a, the coefficient of expan Sion, represents the expansion which takes place when the temper ature is raised from o° C to i° C. The value of a is about 1/273, and we may therefore write the previous equation in the form (273+t)/273. At C the volume of the gas will become zero provided that the relation is valid over this range. It is also apparent that if this singular temperature, which is indicated by the volume relations, is made the basis of a new temperature scale, such that (t +273)° C= T° and o° C=273° the above equation may be written according to which the volume is proportional to the absolute temperature. When this is combined with pv= (Boyle's law) we obtain T/273 or pv/T =R, where R is a constant. This relation is independent of the nature of the gas, and if the volume v refers to the molecular quantity, i.e., the quantity repre sented by the molecular weight, the value of R is found to be the same for all gases. It is known as the gas constant.

Experiments made by Gay-Lussac (18o8) showed further that the volumes of reacting gases and of their gaseous products can be expressed by simple numerical ratios. The interpretation of these simple volume ratios and of the identical behaviour of gases towards pressure and temperature is greatly facilitated by the hypothesis of Amedeo Avogadro (1811), according to which equal volumes of different gases at the same temperature and pressure contain the same number of elementary particles or mole cules. The inability of chemists to distinguish between atoms and molecules was mainly responsible for the lukewarm reception which was accorded to this hypothesis, and its fundamental im portance was not recognized until a clear distinction between these entities was made by S. Cannizzaro in 1858.

Kinetic Theory.

The behaviour of gases, which is sum marized in the equation pv=RT, finds a simple interpretation in terms of the kinetic theory (q.v.). According to this, a gas is supposed to consist of a very large number of small particles which are moving about in all directions with high speeds. The paths of these particles are rectilinear until their direction of motion is changed by collision either with other particles or with the walls of the containing vessel. Collision involves no loss of energy since the particles are perfectly elastic. At any instant, the velocities of individual molecules vary between wide limits and the directions of motion are distributed in random fashion. At a given temperature and pressure, the average speed and the mean distance traversed between successive collisions varies with the nature of the gas. For oxygen, the mean free path at o° and 76omm. is 1 •o X 1 o and the average velocity is 461 metres per second.Denoting the mass of the molecule by nt and the mean value of the square of the velocity by the average kinetic energy of the molecules is which is a measure of the temperature. On the assumption that the pressure of a gas is measured by the impact of the molecules on the walls of the containing vessel, it may be shown that the pressure is given by where ra is the number of molecules in volume v. Since the temperature is measured by the kinetic energy, it follows at once that the prod uct pv is directly proportional to the absolute temperature as expressed by the equation pv=RT and has a constant value when the temperature is fixed, as required by Boyle's law. If for two different gases, the pressures, volumes and temperatures are the same, and the numbers, masses and mean square velocities are represented and mn2, u22 respectively, then pv= and = 3m21122 from which as required by the Avogadro hypothesis. Since the mean square velocity is given by 3 pv/mn, and the density of the gas by d=mn/v, we may write u= v3 p/d, according to which the average molecular velocities for different gases at the same temperature and pressure are inversely proportional to the square roots of the respective densities. For molecules of the same size the rates of diffusion should be proportional to the velocities, and the above result is accordingly in agreement with the results obtained by Thomas Graham (183 2) in his experi ments on gaseous diffusion. Ocular evidence of the molecular movement postulated in the kinetic theory is afforded by the Brownian movement of microscopic particles suspended in a fluid medium. Such particles must have the same kinetic energy as the surrounding molecules and their visible motion is attributable to the unbalanced effects of molecular bombardment.

Gases at Higher Pressures.

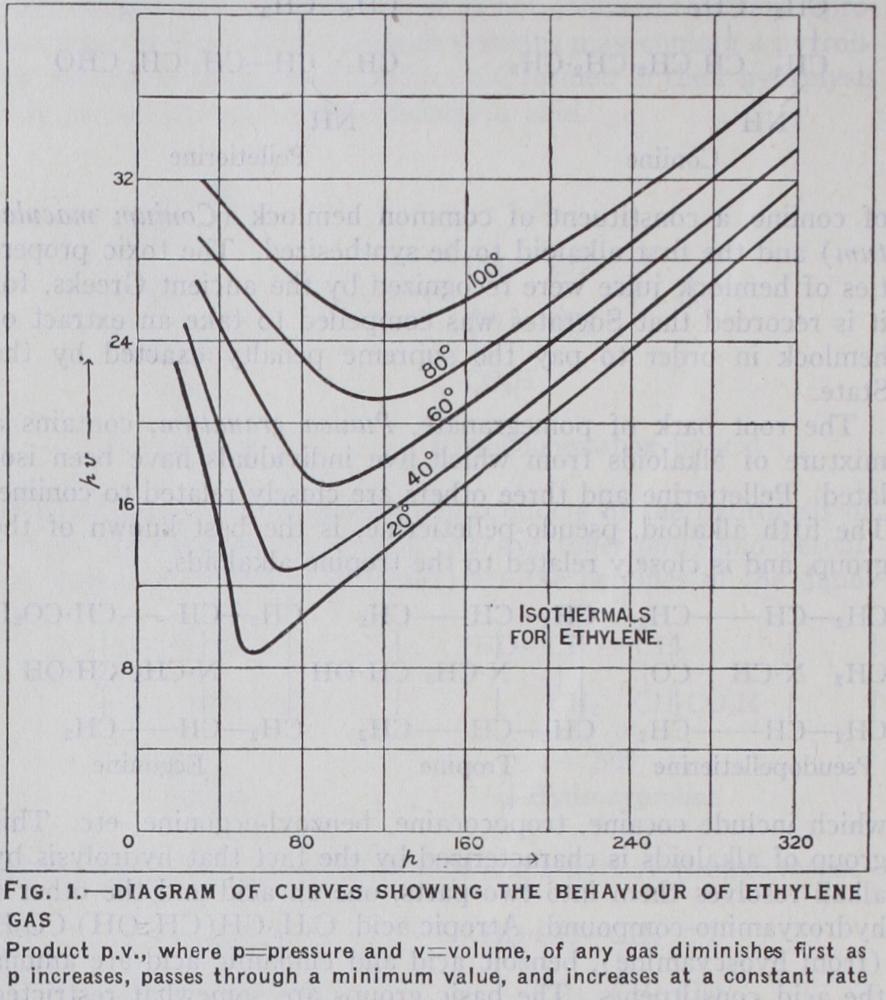

Although the simple or ideal gas laws afford a moderately accurate description of the behav iour of gases at low pressures, there are large discrepancies at higher pressures. The classical experiments of Amagat show that the product pv diminishes at first as the pressure increases, passes through a minimum value and then increases at a constant rate. The general behaviour is shown by the isothermal pv—p curves for ethylene in fig 1. The nature of these curves suggests the incidence of two disturbing factors, one of which tends to increase the compressibility of the gas and the other to reduce it. If the actually compressible space is represented by the intermolecular space, then pv becomes p(v—b) where b is the space occupied by the molecules. Furthermore, if there are attractive forces between the molecules, it may be expected that such forces will tend to reduce the velocity of the molecules which impinge on the boun dary walls of the gaseous molecules, for the latter in their ap proach to the boundary will be subjected to a restraining force. The measured pressure, which is the equivalent of the actual im pacts, should therefore be smaller than the intrinsic pressure, that is to say, the pressure which corresponds with the average velocity of the whole of the molecules in the gaseous system. To obtain the intrinsic pressure, the manometric pressure must there fore be increased by a term which takes account of the attrac tive force. According to Johannes Diderik van der Waals, this correction is proportional to the square of the pressure, or more precisely, inversely proportional to the square of the vol ume, and when the two correction factors are introduced, the equation pv=RT becomes (v—b) =RT, which is the van der Waals' equation. This affords an account of the actual behaviour of gases, as illustrated by the diagram. The constants a and b depend on the nature of the gas. Many alternative forms of such equations of condition have been suggested. The equation of Daniel Berthelot, which takes account of the variation of the attractive force with that of the temperature, is of the type (v—b)=RT and is of special value in the investi gation of problems connected with gases at low pressures. By its use, it is possible to determine with great accuracy the molecular volume and the coefficient of expansion of an ideal gas and from these to derive the values of the gas constant R and of the absolute zero of temperature on the gas thermometric scale.

If a perfect gas were allowed to expand without performing ex ternal work, there would be neither loss nor gain of heat and the temperature would remain constant. In other words, the internal energy of a perfect gas is independent of the volume which it occupies. When, however, the molecules attract one another, the expansion entails the performance of work against these forces; the internal energy of the gas diminishes and its temperature falls. In the absence of attractive forces, the finite volume occupied by the actual molecules will still have a small influence and it may be shown that this factor will produce a rise of temperature. The combined action of these two factors produces what is known as the Joule—Thomson effect. At ordinary temperatures, most gases are cooled, but hydrogen is heated. From this it may be inferred that the attractive forces between the hydrogen mole cules are very small. At lower temperatures the attractive forces increase, and the cooling effect is also obtained with hydrogen when the temperature falls below —8o° C. Other gases show a similar inversion, but the inversion temperatures are well above the ordinary temperatures. The Joule—Thomson effect finds practical application in the liquefaction of gases (q.v.) by the Hampson and Linde methods.

Heat Capacity of Gases.

The heat required to raise the tem perature of a gas varies with the conditions. The molecular heat at constant pressure, Cp, is greater than that at constant volume, the difference being represented by the external work which has to be done when the volume increases. For a gas defined by pv=RT, the expansion per degree is v/T, and the work pv/T =R. In heat units, this is approximately 2 cals., and therefore — = 2. Per gram-molecule the kinetic energy of the gas is E= where N is the Avogadro number, and the incre ment of kinetic energy for one degree rise in temperature is cals. This value should be independent of the temperature and of the nature of the gas. It represents the smallest possible value of C„ and corresponds with Cp = 5.o and 'y = = 5/3. Actual measurements made with monatomic gases are in good agreement with these theoret ical deductions. Within the limits of error the value of C, for helium is 3•o over the range —250° C to 2,350° C, and measurements of the velocity of sound indicate that the value of 7 for the monatomic inert gases, mercury vapour and the alkali metal vapours is 5/3.For gases which contain more than one atom in the molecule, the observed values of and are not only much larger, but they increase with the temperature. For water vapour the value of C is given by The molec ular heat ratio for polyatomic gases is less than 5/3 and in gen eral it diminishes with increase in the number of atoms in the molecule, as is indicated by the values for oxygen 1.4o, ammonia 1.33, chloroform 1.15, ethyl alcohol 1.1' and ethyl ether 1.03. The ratio depends on other factors, however, as may be seen from the numbers for CH, 1.31, 1.28, 1.22, 1.15, CC1, 1.13, all of which contain five atoms in the molecule. It would seem that the kinetic energy of a monatomic molecule, the mass of which is concentrated in a tiny nucleus, cannot have any other form than that which is associated with its translatory movements. This kinetic energy corresponds, therefore, with three independent modes of motion or degrees of freedom in three direc tions at right angles to one another. In accordance with the Max well—Boltzmann principle of equipartition (see KINETIC THEORY OF MATTER) the energy quantity C,, = 3.o should be equally divided between these, and it follows that each degree of freedom is asso ciated with a heat capacity approximately equal to one calorie.

In diatomic molecules, there are two mass centres relatively widely separated and such systems suggest the possibility of other degrees of freedom associated with intra-molecular movements, vibratory in type, of the atoms within the molecule, and with rotational or precessional motion of the molecule as a whole. At very low temperatures, the comparatively feeble impacts between the slowly moving molecules may not be sufficient to give rise to such movements, and in this connection it may be noted that the value of C„ for hydrogen at low temperatures is three calories per degree. At these temperatures diatomic hydrogen would therefore seem to behave as a monatomic molecule. In general, the observed variation of the heat capacities of polyatomic gases with the temperature is, however, difficult to reconcile with the equipartition theory if all the molecules are supposed to have the same number of degrees of freedom. It would seem necessary to assume that those collisions for which the impact exceeds a certain critical value give rise to additional degrees of freedom. The total energy of the gas will then be the sum of the energies of that fraction for which the impacts are less than the critical value and of the fraction for which the impacts are greater than this.

An alternative basis of explanation is afforded by the quantum theory (q.v.). According to this, the exchange of energy between matter and space is a discontinuous process, radiant energy being absorbed by material systems in the form of discrete units or quanta, the magnitude of which is determined by the frequency v as expressed by the equation c=hv where h is a universal constant. The frequency of the absorbable radiation depends on the elastic constants of the molecules, and by the application of statistical considerations, the total energy absorbed by a material system at a given temperature and its dependence on the temperature may be calculated. The quanta associated with the translational movements of the molecules are very small, and for these the process of energy exchange is practically continuous and there fore in accord with the equipartition theory. As the temperature increases, larger quanta become available, and in the form of en ergy of the appropriate frequency such quanta are absorbed by the gaseous molecules in accordance with the statistical formula. In this way it appears to be possible to account for the observed facts.

Viscosity and Conductivity.

There are certain properties of gases, e.g., the viscosity and thermal conductivity, which de pend on the mean free path which is inversely proportional to the chance of collision. The viscosity or internal friction is a measure of the inherent tendency towards the equalization of the velocities of portions of gas which are moving relatively to one another. It may be shown that the viscosity i is given by n= idlu, where d is the density, 1 the mean free path, and u the average velocity of the molecules. If, at constant temperature, the density is doubled, the mean free path will be halved, and it follows that the viscosity is independent of the pressure. If the temperature is raised at constant volume, it would appear that the viscosity should increase in proportion to the square root of the absolute temperature. The actual increase is greater and the discrepancy is in part attributable to the circumstance that at lower temperatures and smaller velocities the molecules are more likely to be deviated from their rectilinear paths by the action of the attractive forces between the molecules. Since the viscosity depends on the chance of collision, i.e., on the total effective cross sectional area of the molecules, it is obvious that viscosity data for different gases afford a means for the comparison of the respective molecular diameters.At the ordinary pressure, gases are normally very good elec trical insulators, although well-marked conducting qualities are acquired at very low pressures. Conducting properties may be induced by the action of X-rays, cathode rays, a- or $-particles, light of very short wave-length, or by certain chemical reactions in all of which processes the molecules are converted into ions by the loss or gain of electrons. As a result of the neutralization of the oppositely charged entities, the conducting properties tend to disappear when the ionizing agency is removed. If a difference of potential is created between two parallel plates in an atmos phere of ionized gas, the ions are directed to the plates. If the potential gradient is small, some of the ions may have their charges neutralized before they reach the electrodes, but the num ber of these diminishes with increase in the potential difference and ultimately all the charged particles reach the electrodes and the current reaches a maximum value. Further increase in the potential difference is without effect on this saturation current until the gradient becomes very much larger, when the current begins to increase once more, at first slowly, and then more rap idly, until finally spark discharge occurs. Under these conditions, the movement of the electrons under the influence of the applied field is so rapid that ions may be produced by collision with the molecules of the gas. The minimum potential gradient required for this is termed the ionizing potential. The value of this for a particular gas depends on the precise nature of the electron expelling process. Even when the velocity of the electron is insufficient to ionize the molecules of a gas, it may be able to displace an electron from one orbit to another. The character istic potential in this case is known as the resonance potential. Such electron displacements are accompanied by the emission of light of characteristic wave-length and the effects in general can be interpreted in terms of the electron theory of atomic structure.