The Solid State

THE SOLID STATE General Characteristics.—Over a long period it was cus tomary to speak of crystalline and amorphous solids, but the grounds on which this distinction was made are now regarded as unsatisfactory. Newer methods of analysis have in fact shown that many apparently amorphous substances are definitely micro crystalline, while others appear to represent supercooled liquids of very high viscosity. The solid state is now generally identified with the crystalline condition, and matter in this form is char acterized by its resistance to shearing stresses and by the fact that its physical properties vary with direction. This "anisotropy" of solids presents therefore a very definite contrast to the isotropy of liquids and gases. When crystals are formed under the usual conditions by the cooling of a liquid, they show a regular polyhedral structure and their physical properties are in general related to the external form (see CRYSTALLOGRAPHY). The normal development of such crystals involves a time factor, and when the conditions are such that separation of the solid takes place rapidly, there is a tendency towards the formation of granular aggregates in which the recognition of crystalline character may be a matter of some difficulty. In the matter of rigidity, the crystalline and liquid states may be said to overlap. The highly viscous, isotropic substances exemplified by the glasses, pass into the condition of fluid liquids in a gradual and continuous manner when the temperature is raised ; there is no sudden transition in the properties such as is observed with crystalline solids at the melting-point. On the other hand, although most crystals are rigid and fracture when subjected to pressure, there are others in which the forces associated with the crystal structure are so weak that the crystals can be easily distorted and made to flow. Their behaviour in this respect simulates that of liquids, but they have the optical properties of crystals and possess a definite melting point.

The directional properties and geometrical forms of crystalline solids are directly connected with regularities in the arrangement of the atoms or molecules within the crystal. These are no longer free to move from point to point, but occupy definite mean positions in the space lattice of the crystal. Their kinetic energy is represented by small vibratory or oscillatory movements about these mean positions. When, by a sufficient rise of temperature, the amplitude of the oscillatory motion becomes sufficiently great for the molecules to escape from the action of the force which tends to restore them to their mean positions, the solid melts and the vibratory motion is replaced by the random translatory motion characteristic of the liquid state. The determination of the ar rangement of the mean positions has been made possible by the fact that the regularly disposed rows and planes of atoms (mole cules) give rise to interference effects when the crystals are sub mitted to a beam of X-rays, that is to say, to radiation of a wave length which is of the same order of magnitude as the distances which separate the atomic centres. The X-ray spectra obtained in this way by M. Laue, W. H. and W. L. Bragg and others afford precise information relative to the architecture of the crystals. For strongly polar substances, such as sodium chloride, it is found that the points of the crystal lattice are occupied by positively charged sodium atoms and negatively charged chlorine atoms. Each sodium ion bears exactly the same relation to six chlorine ions which may be supposed to occupy the central points of the faces of a cube which has the sodium ion at its centre. Each chlorine ion is similarly disposed with respect to six sodium ions. The material structural elements, in other words, are the sodium and chlorine ions, and molecules of sodium chloride in the ordinary sense are non-existent. Substances of non-polar char acter give X-ray spectra, on the other hand, which clearly show that the lattice points are associated with molecular units which are, however, oriented in a perfectly definite manner. The pat terns presented by such structures can always be described in terms of a unit or elementary lattice which may contain one, two or more molecules.

Polymorphism.

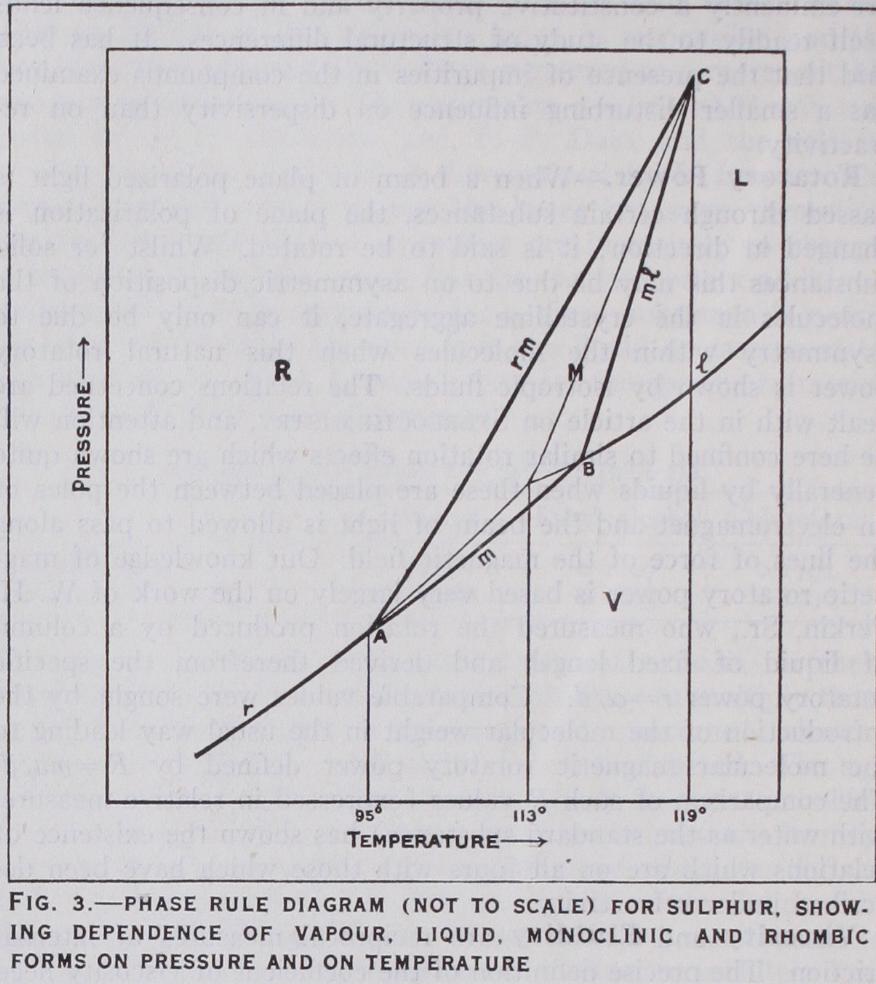

The one-time supposition that every sub stance was unique in its crystalline form has been definitely dis proved by the discovery of isomorphism, according to which differ ent substances may crystallize in the same form, and of polymor phism, according to which the same chemical substance may have different crystalline forms. In some cases, e.g., the rhombic and monoclinic forms of sulphur (q.v.), the two crystalline forms are interconvertible. The change takes place at a definite temperature known as the transition temperature. Below 96° C rhombic sul phur is the stable form ; above 96° the stable form is monoclinic and melts at 119°. Superheating readily occurs, however, and rhombic sulphur may be readily heated to its melting-point 013'). The transition temperature is the only temperature at which the two solid forms can coexist in equilibrium at atmos pheric pressure and at which their vapour pressures are therefore the same. The relations between the two solid forms at the transition point are clearly very similar to those between a solid and the corresponding liquid at the freezing-point of the latter. In some cases, e.g., benzophenone, the two crystalline forms are not interconvertible. One of them is unstable at all temperatures and the transition point (i.e., the point of intersection of the vapour pressure curves) is higher than either of the melting points. When a substance can exist in several crystalline forms the equilibrium relations may be of rather complex character, but the correlation of these is greatly facilitated by the use of the phase rule. According to this, the number of phases, i.e., the physically distinct parts of a system, which can coexist in equi librium is determined by the number of the components. This represents the smallest number of chemical constituents in terms of which the composition of the several phases can be expressed. If P is the number of phases and C the number of the components, the maximum value of P is C-1-2. When this relation obtains, the equilibrium is completely defined by the nature of the system and the variable factors represented by temperature, pressure and concentration can have only perfectly definite values. If P=C+1, one of these factors must have a value assigned to it before the equilibrium is determined. If P=C, two such factors must have determined values. The number of the variables to which arbitrary values must be given to specify the precise nature of the equilibrium is termed the number of degrees of freedom (F) and in accordance with the "phase rule," F=C+2—P. In the simplest possible case where C=1, the number of degrees of freedom is 2, I or o according as P=1, 2 or 3. The whole of the relations involved can be conveniently represented by a diagram on which the pressure and temperature are taken as the co ordinates. Such a diagram, showing the relations between rhombic, monoclinic, liquid and sulphur vapour is presented in fig. 3. In variant systems (F=o) are represented by the points at which three curves intersect. The point A corresponds with the system rhombic-monoclinic-vapour, B with monoclinic-liquid-vapour and C with rhombic-monoclinic-liquid. Univariant systems (F= 1) are represented by points on the curves. The curves r, m and 1 define the respective conditions under which rhombic and vapour, monoclinic and vapour, liquid and vapour can coexist in equilibrium. In the same way the curves rm and ml give the con ditions for equilibrium between rhombic and monoclinic and between monoclinic and liquid. Bivariant systems (F=2) are those represented by all other points and the regions of stability of the single phase systems—rhombic, monoclinic, liquid and vapour, are shown by R, M, L and V.Heat Capacity.—According to the empirical relation dis covered by P. L. Dulong and A. T. Petit (1819), the product of the specific heats of the elements and their atomic weights is approximately constant=6.4. This relation was confirmed by Regnault, but it was found necessary to recognize that the non metallic elements of low atomic weight are exceptions to the rule in that their atomic heats are abnormally small, e.g., carbon 1.8, boron 3.7, beryllium 3.7, silicon 3.8, phosphorus 5.4. According to F. E. Neumann and H. Kopp the molecular heats of compounds can be expressed approximately as the sum of the atomic heats of the constituent elements, from which it may be inferred that the heat capacity is within narrow limits the same whether the elements are free or chemically combined. The experimental results summarized in the rule of Dulong and Petit are in agree ment with the deductions from the classical kinetic theory. Ac cording to this the atoms in the solid element have three inde pendent modes of movement associated with the three directions of space, and since each degree of freedom corresponds with a heat capacity of R/2 calories, and kinetic energy of the oscillatory type is necessarily associated with an equivalent amount of po tential energy, it follows that the atomic heat capacity is 6X R/2= 6.o calories. This value should, however, be independent of the temperature, which is contrary to experiment, for measure ments of the specific heats of the elements and of their compounds at very low temperatures have shown that the heat capacity be gins to fall rapidly when the temperature is sufficiently low and tends towards a zero value. The explanation of this behaviour represents one of the most important achievements of the quantum theory. Albert Einstein has indeed shown that the observed de pendence of the heat capacity on the temperature is in general agreement with the requirements of the quantum theory of heat exchange. The formula given by Einstein, which assumes that the energy absorbed is associated with a particular frequency. has since been modified by Peter Debye and others. According to these later views the characteristic frequency of Einstein re presents the upper limiting value of the complete series of frequencies which can actually be absorbed by the atoms. The observed atomic heats of copper and those calculated on the basis of the quantum theory are compared below : Temperature (A) • 88.0 Cp (obs.) . . . 0•22 0•54 4'57 Cp (calc.) . . . 0.15 3'39 5'75 At relatively high temperatures there is no difference between the requirements of the classical and quantum theories. The fact that the value of becomes considerably greater than 6.o at very high temperatures—for tungsten at 2,00o° C, Co = is said to be due to the thermal agitation of the electrons. Electrical Conductance.—Electrical conducting power similar to that possessed by metals and alloys is shown by certain non metals, e.g., by carbon in the form of graphite, by compounds of some of the less electropositive metals with elements of the oxygen group, e.g., pyrites, oxides of lead and iron, and also by compounds of the type represented by At very low tem peratures this metallic conducting power increases very greatly. The resistance of tin becomes vanishingly small at 3.8° A, and that of thallium at 2.3° A. In other cases, e.g., platinum and calcium, the resistance falls to a low limiting value which is independent of the temperature. The supposition that metallic conduction of electricity and heat is due to the movement of free electrons is difficult to reconcile with the very small heat capacity of the electrons, and the suggestion has been made that a metal represents a structure with interleaved ionic and electron lattices, electrical conductance being associated with the move ment of the electron lattice through the ionic lattice. Electrolytic conductance of the type exhibited by fused salts and salt solu tions is also met with in the case of certain solid salts. Whereas the conductance in liquids is associated with the movement of both positive and negative ions, the passage of the current through these solid compounds is due either to the positive or to the negative ion. In silver chloride and cuprous sulphide the carrier is the metallic ion, whereas the chlorine ion is the migratory con stituent in lead chloride. Both metallic and electrolytic conduc tion are shown by other solid salts.