Adc

ADC is the minor arc, and APEC the major arc, between A and C.

The figure composed of an arc and the chord joining its extrem ities is a segment of the circle. In fig. 1, ADCB and APECB are respectively the minor and major segments made by the chord AC. A sector of a circle is the figure formed by two radii and one of the arcs joining their extremities. The angle between these radii and within the sector is called the angle of the sector. Thus ODKC (fig. I) is a sector, and DOC its angle.

Geometrical Properties.

A number of properties of the cir cle are direct results of the symmetry and regularity of the curve. For instance, if two chords in the same circle are equal, the arcs corresponding to them are equal; if two sectors of the same circle have equal angles, they have equal arcs, and contain equal areas, etc. A useful property of this kind is that every chord is bisected by the perpendicular drawn to it from the centre. This allows the centre to be found when the circle is given, and to draw the circle when three points on it are given. Thus, to construct the circle through H, P and Q, draw the perpendicular bisectors LO and RO to HP and PQ as in fig. 1, and take as centre the point 0 where these meet.A less evident property is that, when any arc is taken, the angle between the lines joining its end-points to the centre is double the angle between the lines joining these end-points to any point on the remaining part of the circle, each angle being measured in the position facing the arc. In fig. 1, by using the minor arc CD, the angle COD is double the angle CED, and also double the angle CAD. By using the major arc APE, the outer (reflex) angle AOE is double either ACE or ADE. An immediate consequence is that the angle ACE is equal to the angle ADE. Here A, C, D and E are any four points on a circle so placed that C and D lie on the same arc having A and E for end-points. The theorem is com monly stated in the form : angles in the same segment are equal. (To exhibit the segment it is necessary to join AE.) It is a prop erty of wide application, and numerous instances of it may be seen in fig. 1 by joining various pairs of points. Thus the angles CAD, CED, CGD, CQD (when the lines CQ, QD and CG are drawn), are equal. In particular, the angle in a semi-circle is a right angle. Closely related to this is the theorem that a four-sided figure whose four corners all lie on the same circle has the sum of either pair of opposite angles equal to two right angles. The con verse is true that if the sum of one of the pairs of opposite angles of a four-sided plane figure is two right angles, a circle may be drawn to pass through the four corners.

It is readily seen that a straight line whose shortest distance from the centre is less than the radius cuts a circle in two points, and that a line whose shortest distance is greater than the radius does not meet the circle at any point. The intermediate case oc curs when the line is at a distance from the centre equal to the radius, as is the case with SPT (fig. 1). Such a line has only one point in common with the circle ; it is said to touch the circle and is called a tangent to the circle. The tangent at any point of a circle is the line through that point drawn at right angles to the radius ; thus OPT is a right angle. The tangent at P is the limit ing position approached by a chord PQ, drawn through P, as the other extremity Q approaches P. The chord must be prolonged as shown in the figure, in order that it may not be lost as its length vanishes. It is known that the perpendicular OR from the centre falls on the middle point of the chord. As Q moves to Q', R moves to R', and, as Q approaches P, R approaches P also. Finally the right angle ORQ approaches the limiting position OPT, and the chord PQ, prolonged sufficiently, is finally represented by the tangent PT at right angles to the radius OP. This second' view of a tangent, as the limiting form of a short chord, is more gen erally applicable than the former, being valid for curves other than circles. It also enables many tangent theorems to be recog nized as the limiting forms of related theorems on chords, and leads to a better understanding of tangent relations.

From a point F outside a circle two tangents may be drawn. The points of contact G and G' of these may be found by first drawing the tangent at a point P on the circle, finding with the compasses a point S on this such that OS=OF, and then finding G and G' on the circle and at distance from F equal to PS. The angle made by a tangent with a chord through its point of con tact is equal to the angle in the segment on the other side of the chord. Thus the angle FGD is equal to the angle GED. An im portant theorem on intersecting chords follows readily from the law of equal angles in a segment. If two chords intersect, the product of the distances of the extremities from the point of in tersection is the same for either chord. Thus, in fig. 1, AC and DE intersect at B. The figure represents the case where AB contains 4.5 units, BC 3.2 units, DB I unit, and BE 14.4. It will be seen that 4.5X3.2=-1X14.4. The relation remains true when the chords have to be prolonged to meet outside the circle, as AD and CE, meeting at F. In the figure AF= 7.2, DF=3.2, CF= 1.6 and EF=14.4, so that AFXDF=CFXEF, each being 23.04. In the case of external intersection each of the equal products is also equal to the square of the tangent from the point of inter section. In the figure, FG=4.8, the square of which is 23•04. This is one of the cases where the tangent represents a chord whose ends are coincident.

Circle Constructions.

The circle plays an important part in the problems of constructive geometry. This will be easily un derstood when it is remembered that, in the traditional view, a geometrical solution means a solution by ruler and compasses; that is, the only steps available are to rule a straight line through two given points and to draw a circle having a given centre and radius. It is therefore a matter of importance to the student of geometry to be able to construct circles to satisfy various standard sets of conditions; and several of these processes will be indicated briefly : I. Circle through three given points. The method of finding the centre by the right bisectors of the joining lines has already been given. When the three points are thought of as the corners of a triangle, the circle is said to be circumscribed to the triangle.2. Circle touching three given straight lines. Bisect the angles between two of the lines land in, obtaining a pair of bisector lines a and b. Bisect in the same way the angles between 1 and the third line n by a pair of bisectors c and d. The centre of a circle touching 1 and m must be equidistant from 1 and m, and so must lie either on a or on b. The centre of a circle touching 1 and n must be either on c or on d. Four solutions are obtained, the positions of the centre being the intersections of a and c, of a and d, of b and c, and of b and d. The circle that lies between the given lines and touches them is said to be inscribed to the triangle.

3. Circle through two given points and touching a given line (which does not pass between the points). Let A and B be the given points, and 1 the given line (fig. 2). Let AB cut 1 in 0. Draw any circle c through A and B, by taking as centre any point on the right bisector of AB. Draw the tangent OT touching c at T. Find points H and K on l so that K0=OH=OT. The circle through A, B and H and the circle c, through A, B and K will each be a solution of the problem. The proof is briefly that so that OH and OK are each of the right length for a tangent from 0.

4. Circle through a given point and touching two given lines. Let 1 and m (fig. 2) be the given lines, and A the given point. Draw n, the bisector of that angle between 1 and in in which A lies.

Draw Al perpendicular to n and prolong to B so that LB=AL.

The circles and constructed as in 3 to pass through A and B and to touch l will then consti tute the two solutions of the problem.

Circle constructions in which some of the conditions are that the circle should touch certain given circles require refined geo metrical methods. A celebrated case of this type is Apollonious's problem : —to construct a circle to touch three given circles. If the three circles are entirely external to one another, this problem admits of eight solutions. A number of problems of this kind, due to Jakob Steiner and others, are discussed by Coolidge (see bibl.). It is often useful to remember that a circle through two given points may have its centre anywhere on the right bisector of their joining line, and that a circle touching two given intersecting straight lines has its centre anywhere on either of the lines bisecting the angles between them. A circle through a given point and touching a given line has its centre on a curve known as a parabola; but this fact is not of much direct assistance in finding constructions.

In many cases a point moving under specified conditions traces a circular path. The definition of the circle shows that this curve is the locus (or path) of a variable point whose distance from a fixed point remains constant. But there are numerous other ways in which the circular path may be recognized. If the base of a triangle is fixed, and the angle at the vertex is of constant magni tude, the moving vertex traces an arc of a circle as long as it re mains on the same side of the fixed base ; the property involved here is that of equal angles in a segment. If the base of a triangle is fixed, and the other two sides are in constant ratio, the mov ing vertex traces a circle which encloses one of the fixed vertices. If the sum of the squares of the distances of a variable point from two fixed points is constant, the point traces to a circle whose cen tre is half-way between the two fixed points.

Analytic Treatment..

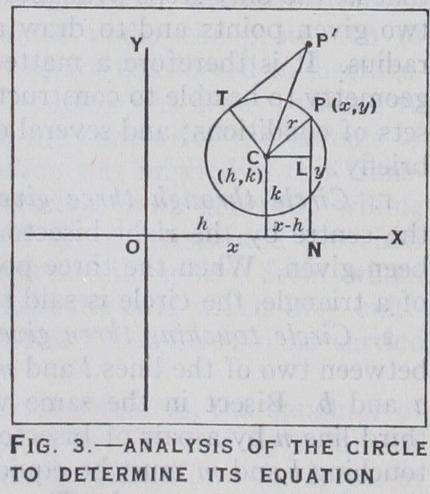

We may take for axes of reference two lines OX and at right angles; and, drawing PN perpen dicular to OX from any point P, denote by x and y the measure ments ON and NP. The two quantities x and y are called the co-ordinates of P, and the posi tion of P depends on their values. the point P is denoted by (x, y). If C is a fixed point (h, k), P will be restricted to a circle of centre C and radius r provided CP = r ; i.e., = or = if CL is perpendicular to NP; therefore (I) This is the equation of the circle. The variable point P will lie on the circle if, and only if, (I) is satisfied.The equation (2) may be written in the form which is equivalent to (I) if h=—a, k=—b and The last of these conditions is not possible for any real value of r if is negative; but, if is positive, the equation (2) is seen to represent a circle whose centre is (—a,— b) and radius -\/ The constants a, b and c in (2) may be determined to satisfy specified conditions, and the circle becomes then definitely fixed. For instance, if the circle is to pass through three given points, the co-ordinates of these must satisfy the equation (2) , and, on substituting them for x and y, three equa tions are obtained giving a, b and c. If the point (x, y) is not on the circle, but outside it, as at P' (fig. 3), the left-hand side of equation (2) is not equal to zero, but, when written as or is seen to represent (if P'T is a tangent), which is A point (x, y) from which the tangent to the circle (2) is equal to the tangent to the circle (3) satisfies the equation b'y+c'; i.e., 2 (a—a') • This equation (if the circles (2) and (3) have not the same centre) is of the first degree, so that the point (x, y) lies on a fixed straight line, called the radical axis of the circles. If the circles (2) and (3) have two points in common, the radical axis is the line joining these points. The equation represents, for different values of c, different circles of which any two have OY for radical axis. These circles are said to form a coaxial system. If c is negative, all the circles pass through the same two points on OY. If c is positive, none of the circles inter sect. In either case one circle of the system may be found to pass through any given point not on OY.

The equation of the tangent at a point (x,, on the circle (2) may be shown to be x x+yly+a (x+x)+b(y+y,)+c=o. (4) If, however, y) is not on, but outside the circle, equation (4) represents the polar of y,) that is the straight line join ing the points of contact of tangents from y,).

Mensuration of the Circle.

The ratio of the length of the circumference to the diameter is the same for all circles. This number can only be calculated approximately, and is 3.141592 as far as 20 places of decimals. The true value of this number is always denoted by 7r, and has been recognized from antiquity as a most important constant. 27 may be used as a rough approximation to 7r. Mathematicians have devoted an incredible amount of time to the calculation of this number, even reaching hundreds of decimal places. It is difficult to believe, however, that more than about ten figures could ever be put to any practical use; in fact is likely to serve well enough. If r is the radius, the length of the whole circum ference is 27rr.Let s measure the arc AB, c the chord AB, and h the distance from the middle of the arc to the chord. By dividing up the area of the sector AOB as suggested (fig. 4), and reasoning from the sum of a number of small tri angles, it is inferred that the area of the sector is i rs; and the area of the whole circle is 2rX 27 It has long been known that no construction by ruler and com passes can furnish a straight line of length equal to that of the circumference of a given circle, or a square equal in area to a given circle; though in ancient times "squaring the circle" was con sidered an important unsolved problem. Also a straight line can not be constructed equal to any given arc of a circle, though ap proximate methods exist which work well for an arc which is not too large compared with the radius. For instance, produce AB to P, making BP=1 AB. With centre P and radius PA draw an arc cutting at Q the tangent at B. Then BQ = the arc AB ap proximately. For an arc forming a quarter circle the error is about one part in 300. For A of the circumference the error is less than one in a million. An approximate relation between c, li and s is For a value of h less than of c, this gives s to within of its value. The radius of the circle does not appear in this relation. As an example of its use, if c=144, and s=144.2, then h=3.3• BIBLIOGRAPHY.-Euclid, Elements, Bk. III ; J. L. Coolidge, A Bibliography.-Euclid, Elements, Bk. III ; J. L. Coolidge, A Treatise on the Circle and the Sphere (1916) ; H. S. Hall and F. H. Stevens, A School Geometry (1924) ; D. M. Y. Sommerville, Analytical Conics (1924).