And Occupations

AND OCCUPATIONS The coal miners of Great Britain, that is, those in employment at the mines, numbered 975,710 persons in 1927; and when the unemployed, the women and children and various surface workers are included, this figure likely exceeds 3,000,000. Differing greatly as between districts in point of disposition and dialect, they have three characteristics in common—independence, suspicion as to motive, and loyalty to their leaders. But whereas the Welsh miner is, owing to his Celtic temperament, impulsive, warm-hearted, imaginative and voluble, a good friend and a good hater, the miner of the northern coalfields is more stolid, slower to action and less easily reconcilable to altered conditions. This is instanced by the fact that, though the Welsh miner will come out on strike more readily than the northern miner, once the latter is on strike he will not so readily return to work as the Welshman. One of the qualities which coal miners share the world over is their helpful ness towards each other in times of distress.

In order to understand the miners one has to have regard to their history. Their characteristics are largely the outcome of their environment. Whereas the industries in which most other manual workers are engaged are of recent origin, coal mining is a very ancient occupation. Since—and probably before—King Henry III. granted to the goodmen of Newcastle-on-Tyne a licence to dig coals in the Castlegarth, there have been coal mines in Britain. In 1245 mention is made of the ways of persons em ployed in getting coal. In 1291 there is mention of the grant of a mine at Pittenerief in Fifeshire to the Abbey of Dumfermline; and coal was introduced into London in 1306.

Living in communities apart from other people, the miners have in the process of time acquired characteristics and a termi nology peculiar to themselves. The nature of their work in the silence and dark of the mine conduces towards rumination. The long hours and arduous work have been preventative of leisure. Their sense of grievance has come down from the "bad old days" when women and young children—the latter of eight years and younger—were employed for i o to I 2 hrs. in degrading work below ground, and when "the colliers and salters of the North were bondmen, until 1775, when by Act 15 Geo. iii. C 28 their fetters were struck off" (Wade's History of the Middle and Working Classes, p. 393) . "They were in a state of slavery or bondage, bound to the collieries and salt works where they worked for life, and transferable with the collieries and salt works when their original masters had no further use for them" (Wade's British Chronology, p. 53o, 2nd ed. 1841). But all that is past and gone and is only here referred to as explanatory of much which is little understood in the coal miner of to-day.

Occupations.

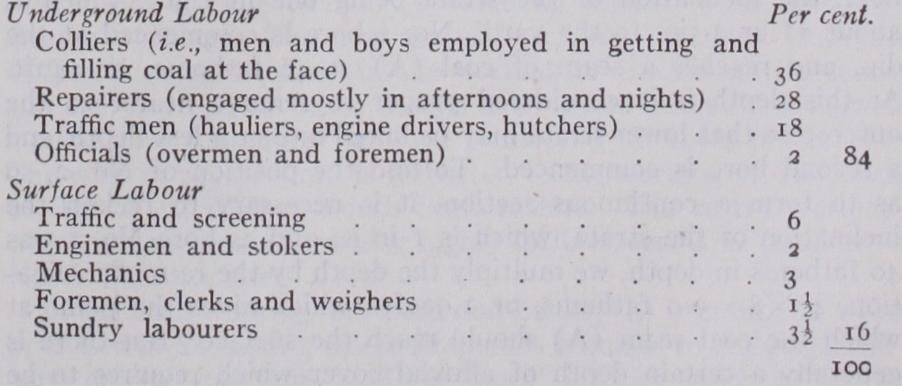

In spite of the developments and improve ments rendered possible in mines by the forward march of science, manual labour still plays a most important part in coal mining, and as much as from 6o to 70% of the cost of "getting" and delivering the coal into wagons is represented by workmen's wages. The number of occupations covered by the terms coal miner, collier or pitman, which are synonymous, are much greater than is commonly supposed. Thus, taking the case of a large group of collieries in South Wales, the late Mr. Hugh Bramwell, when chairman of the South Wales Coal Owners' Association, in giving evidence before the coal mining organization committee in Sept. 1915, showed the relative proportion of the different classes to be as follows :— Underground labour at collieries comprises the following occu pations, viz.:— Hewers (known also as colliers, ccalgetters, pitmen, pikemen or stallmen).

Shotfirers.

Putters (known also as hauliers, trammers or hurriers). Shifters (known also as repairers, timberers, etc.).

Stonemen (known also as brushers, drifters, ridders, caunch men).

Wastemen (workers in the return airways).

Drivers (known also as pony drivers, horse drivers).

Inclines workers (known also as ginney workers).

Helpers-up.

Rolley waymen (known also as mechanical haulage hands, wagon way men, road corporals).

Waterleaders.

Onsetters (known also as hutchers, hitchers-on, cage loaders). Horsekeeper (known also as farrier) .

Deputies (known also as deputy overmen, firemen, chargemen). Overmen (known also as underlookers).

The proportion of coalgetters, i.e., hewers or colliers, to the total of underground workers for all districts varies between 37 and 4o%, e.g., 1913, 40.8%, 1918, 37.7% (see report of coal industry commission, 1919).

In modern England the standard of living of the miner has been continually rising for a long time, as in other classes of labour. Taking the north of England as an example, the hewers' wages at the beginning of the 18th century were is. to is. 2d. per shift; at the beginning of the 19th century they had doubled, being 2s. 3d. to 2s. d. for a shift of 8 to 12 hrs. and in 1913, the last pre World War year, they were 7s. to 8s. a shift of 7hr., in addition to which they had free house and coal, the value of which was not less than is. 8d. per shift. The chief impression left by an historical review of coal mining in the United Kingdom is the enormous progress made during the last two or three generations in every respect except the return on capital.

The United States of America is frequently quoted as offering a higher standard of living to employees than any Old World country, yet we find a high American authority (Edward T. Di vine, Coal 1925) stating that the home conditions of the anthra cite miners is very indifferent, the sanitary conditions are bad, nor does the standard of living correspond to the expectation created by the earnings. Of the bituminous coal miners the same is said to be true. In the "company towns," where many of the miners have to live, the author epitomizes the situation thus: "The general result is anything but a normal American community of free citizens."