Cacao Cultivation

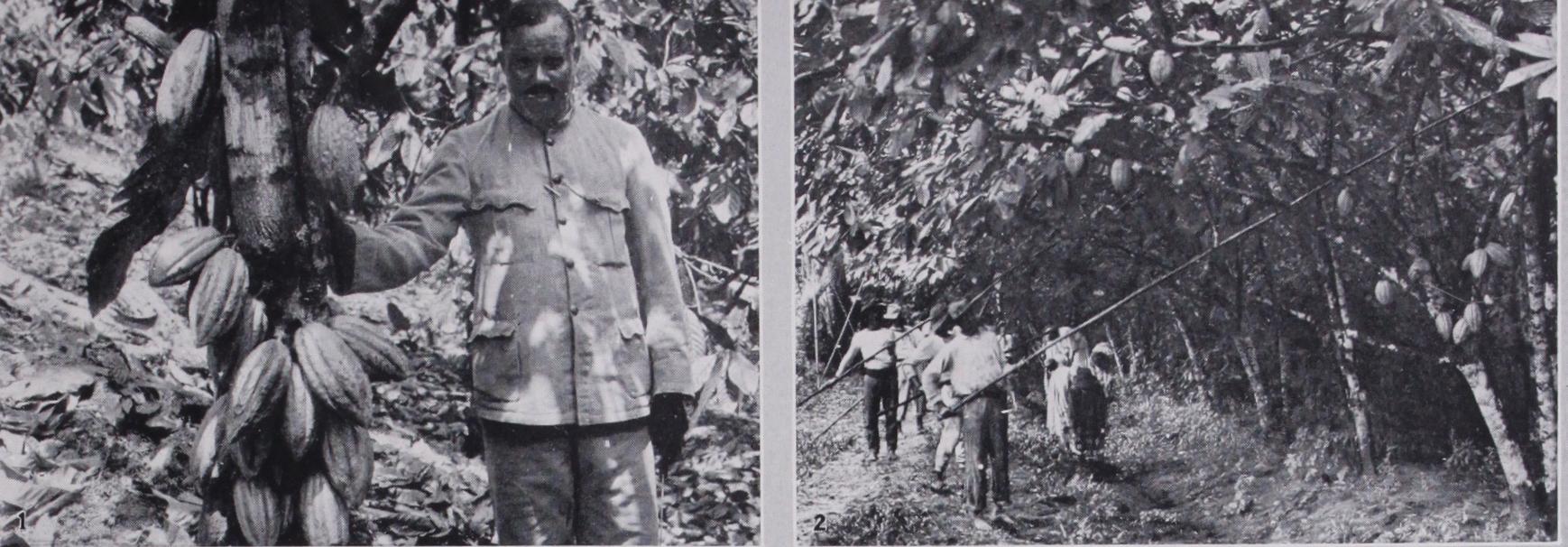

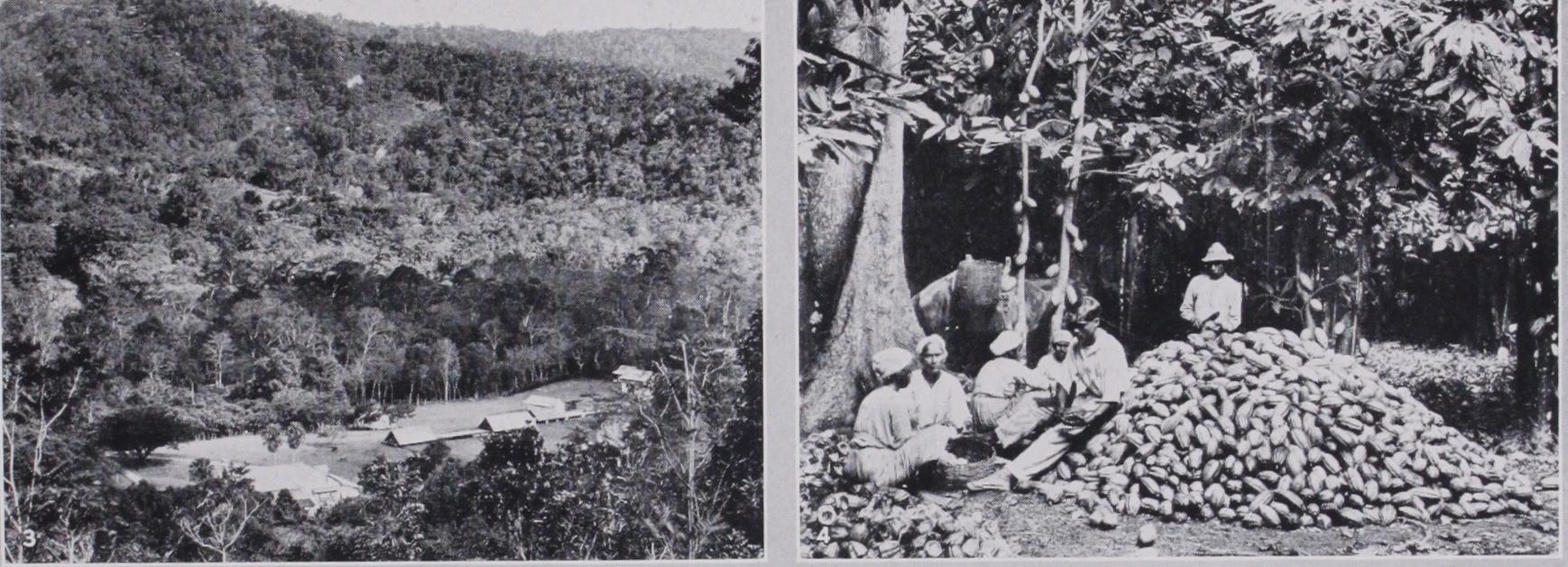

CACAO CULTIVATION Cacao can be profitably cultivated only within 20 degrees north or south of the equator ; it requires a mean shade temperature of 8o°F., and an evenly distributed rainfall of 5o to I soin. a year. The cacao tree requires a rich porous soil of considerable depth, and must be protected from the wind; a secluded vale provides the ideal environment.

Planting.

Growers have preferred in recent times to plant the hardy, well-yielding, forastero variety rather than the choicer, but more delicate, criollo. Seedlings are grown in nurseries, or the seeds are used straight from the pod. They are planted from 10 to i8ft. apart, according to the soil, shade, etc. To protect the soil beneath the trees from the glare of the sun either huge shade trees (e.g., the vermilion flowered Erythrina) are grown at inter vals of 4o to soft., or the cacao trees are planted very closely and hedges are grown to provide wind-breaks.

Harvesting the Crop.

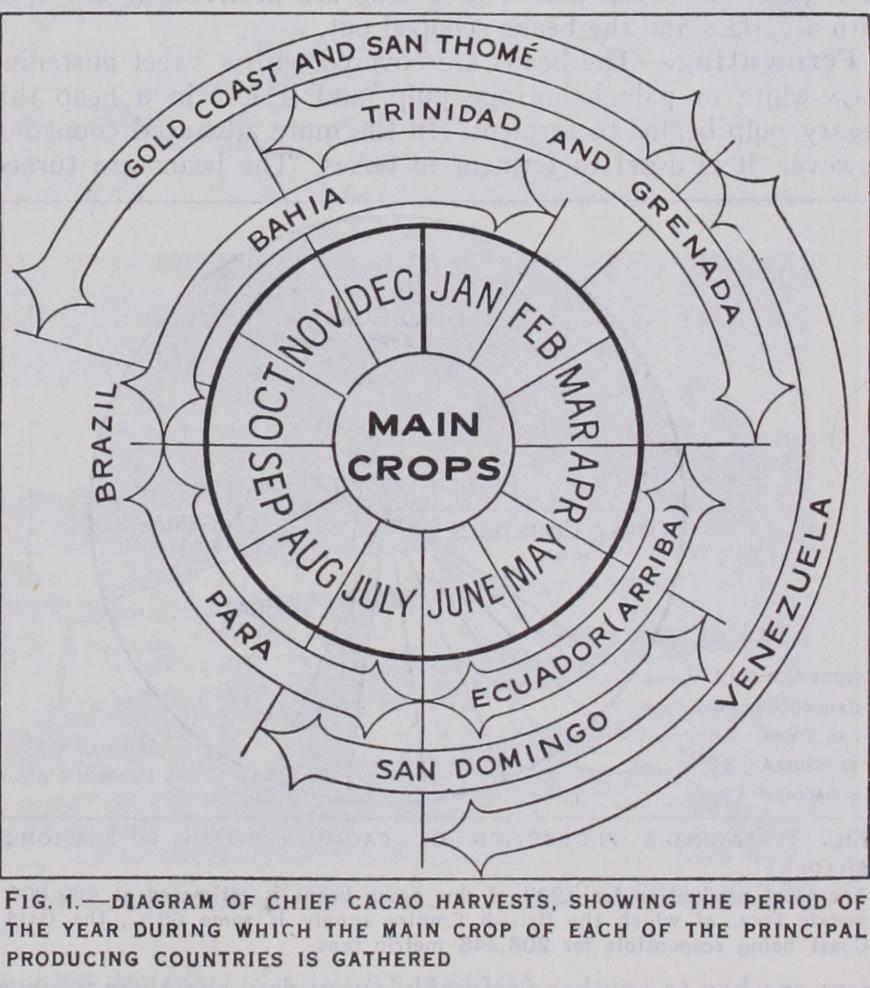

The cacao tree begins to bear in four to five years. The small pink flowers and the succeeding large pods are borne directly on the trunk and main branches.The chief harvesting periods are shown in the diagram, but ripe pods may be found on the tree all the year round. The pods on the higher branches are cut from the tree by a knife at the end of a 2of t. pole, and when placed in a heap are individually cut open with a cutlass and the beans scooped out.

Fermenting.

The beans are covered with a sweet glistening snow-white or pale heliotrope pulp, and if left in a heap this sugary pulp begins to ferment. In the more advanced countries, however, it is usual to ferment in boxes. The beans are turned from one box to another preferably every day, and their temper ature rises to 89°F., 98°F. and 115°F. in one, two and three days respectively, reaching an exceptionally high temperature for yeast fermentation. The criollo variety requires two days' fermentation, and the forastero from five to nine days. The pulp drains away as a fermenting resembling sweet cider. This is allowed to run to waste. A trace of acetic acid produced in the later stages gives the cacao a characteristic pungency resembling vinegar. This is a doubtful advantage, but the total effects of fermentation on colour. flavour and texture increase the value of the bean.

Drying, Washing, Etc.

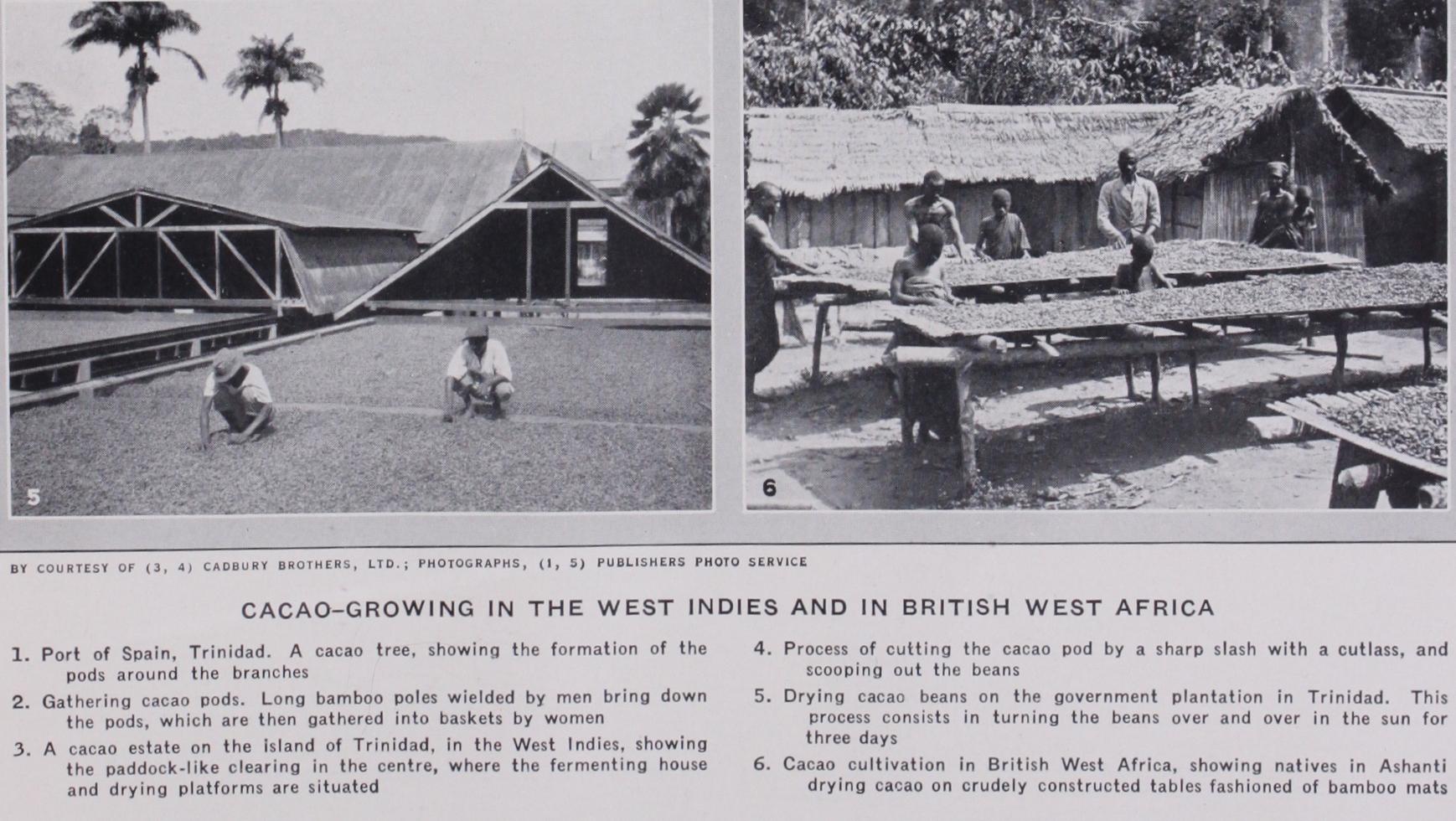

The bean as it comes from the pod contains 33% of water. This must be reduced to 5 or 6% to give a satisfactory commercial product. The drying is generally done in the sun on cement or brick floors, on mats of coconut fibre, or on wooden platforms; or, as on the Gold Coast, on light bamboo mats on trestles. Whilst the best results are always ob tained by the slow and even drying which is produced by turning over and over in the sun for three days, the climate may neces sitate the use of artificial dryers. To a limited extent heated plat forms are used in San Thome, drying rooms in Ceylon and Gren ada, and drying machines in Costa Rica, Bahia, etc.The processes of washing, claying and polishing, peculiar to certain places, have few advantages beyond pleasing the eye of the buyer. In Ceylon and Java the pulp is partly removed by washing and the shell of these beans is fragile and gets broken in handling. In Venezuela a thin coat of red earth is rubbed on to the beans. The similar practice of claying was followed in Trinidad until 1923, when it was prohibited. In some countries polishing machines are used.

Yield.

On an average a full-grown tree may bear 6,000 flowers, of which only 20 will become cacao pods. A pod weighs about 1 lb. and contains 4 oz. of pulp-covered seeds, which yield i z oz. of the dry, cured, cacao beans of commerce. From these figures is derived the startling fact that, taking all trees in the world, the average yield of cacao beans to the tree is not more than two pounds per annum, and even on first-class estates rarely exceeds three pounds.Cacao beans in shape resemble almonds, but are not so pointed ; they weigh about 400 to the pound. The skin, or shell, is brown. The inside of a superior kind of bean is the colour of cinnamon; of ordinary kinds, dark brown or purple; and of poor unfermented kinds, slate colour. The taste is more or less bitter and astringent, nutty, and faintly aromatic.

The leading ports for the shipping of cacao are Accra and Secondee (Gold Coast), Bahia and Para (Brazil), Guayaquil (Ecuador), Port of Spain (Trinidad), Lagos (Nigeria), San Thome (San Thome) and Sanchez (San Domingo). Whilst some manufacturers have agents at certain producing centres, the great bulk of cacao buying is done through brokers and merchants on cost and freight contracts. The chief cacao markets are New York (where there is a cacao exchange), Hamburg, London, Liverpool, Amsterdam and Havre.

Where Cacao Is Grown.

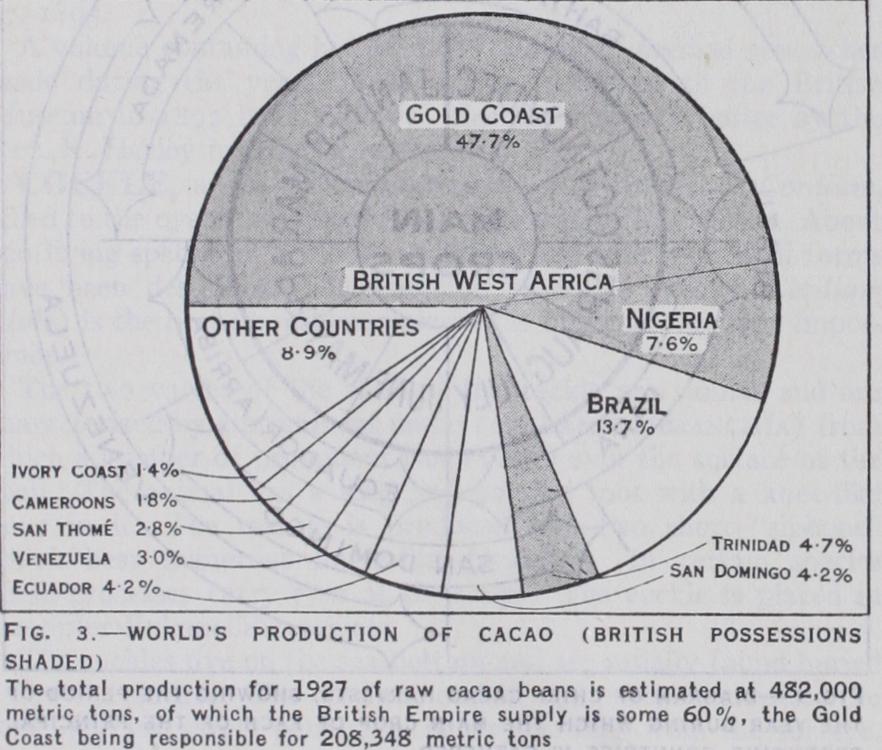

The diagram below gives an ac curate impression of the relative proportions of the world's supply exported by the chief producing centres in 1926: The table below is compiled from a journal published in Ham burg, the Gordian, which is the most reliable source of cacao statistics. It shows changes in cacao production between 1906 and 1926:— The other countries include Costa Rica (5,318), Grenada (4,103), Ceylon (3,372), Jamaica (3,057), Java (904), Belgian Congo, Surinam, Samoa, St. Lucia (494), Dominica (32o) and Cuba. The figures in parentheses are for 1926.The finest type of bean, the criollo, is grown in Venezuela, Cey lon, Java, Samoa, Madagascar and Nicaragua; but in Ceylon, and other places, criollo is being replaced by forastero, and it is doubt ful if the world's production of criollo reaches i o % of the whole. During the first quarter of this century cacao production quad rupled, mainly owing to the increased supply from the Gold Coast. The quantity of Nigerian cacao exported from Lagos is rapidly increasing, and the quality, though still poor, is slowly improving. The output of Brazil has also grown and the sum of its Bahia and Para cacaos has established it as the second largest producer in the world. Trinidad cacao is well known for its good quality and excellent preparation. The Sanchez and Samana cacaos of San Domingo are purchased in New York for the same price as Gold Coast cacao. The Arriba and Machala cacaos of Ecuador are valuable and distinctive, and it is to be regretted that, owing to the outbreak in 1922 of a disease of the cacao tree (appropriately called Witch Broom, Colletotrichum luxificum), their output had been reduced to one-half by 1926.

It will be noted that British possessions are responsible for over 6o% of the world's supply, and the Gold Coast alone for nearly Gold Coast.—The conditions here are unusual, the land being held, and the cacao farms managed, by the native people. It is doubtful if any native-owned industry ever developed with such rapidity as cacao cultivation on the Gold Coast. Figures showing the cacao exported epitomize its history:— The cacao grown is the amelonado variety of forastero. In the early days the preparation of the cacao was poor, but an ever increasing amount of sound, fermented cacao has since been produced. Great credit is due to the natives and to the Govern ment for the manner in which difficulties have been overcome. The presence of the tsetse fly, and hence the absence of pack animals, renders the transport of this immense amount of cacao a difficult problem, which has been solved to a considerable extent by the construction of 495 miles of railways and over 3,000 miles of roads suitable for motor lorries. The difficulty of shipping cacao to ocean liners, which is increased by the presence of a heavy surf, has been countered by the construction of a deep sea harbour at Tak oradi. The two dangers which threaten cacao cultivation—the reduction of rainfall by the destruction of the moisture-drawing forests, and the destruction of the cacao trees by disease or pest—are recognized as problems by the department of agriculture and the educated native.

Prices.

Below is a chart showing the variation in price of four different classes of cacao from 1913-27. The chief points of interest are the Government control of prices during 1918, and the phenomenal rise and fall which followed the removal of the control.The prices given in the chart do not include import duties. The table below shows changes in import duty; since 1919 British empire-grown cacao has had a preferential duty.

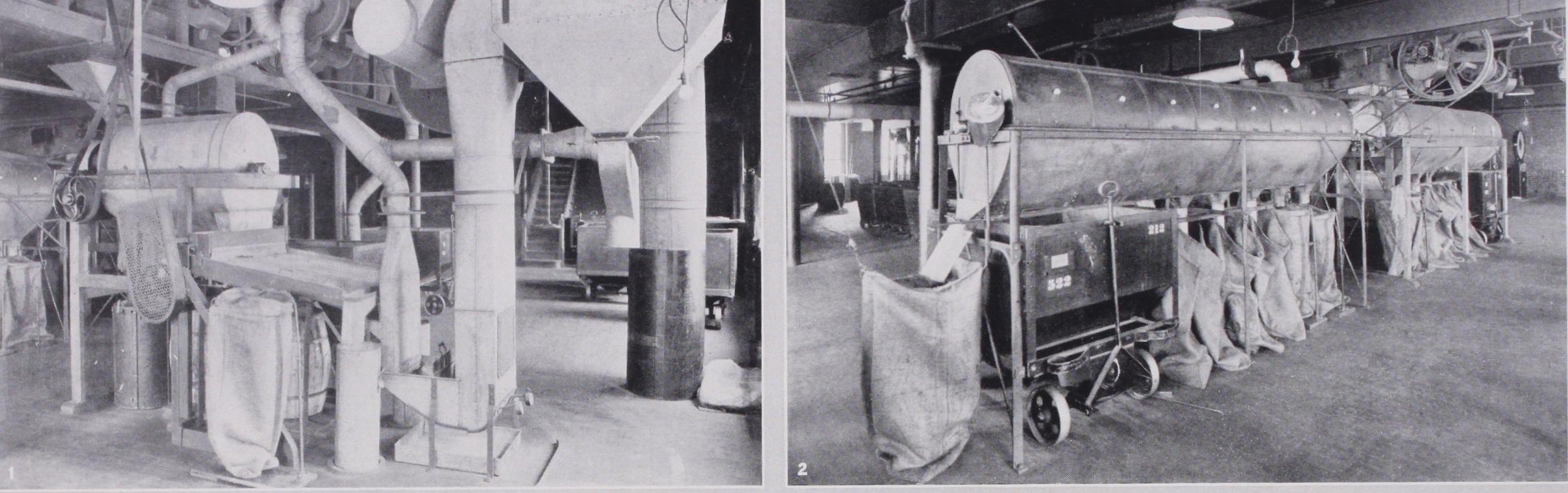

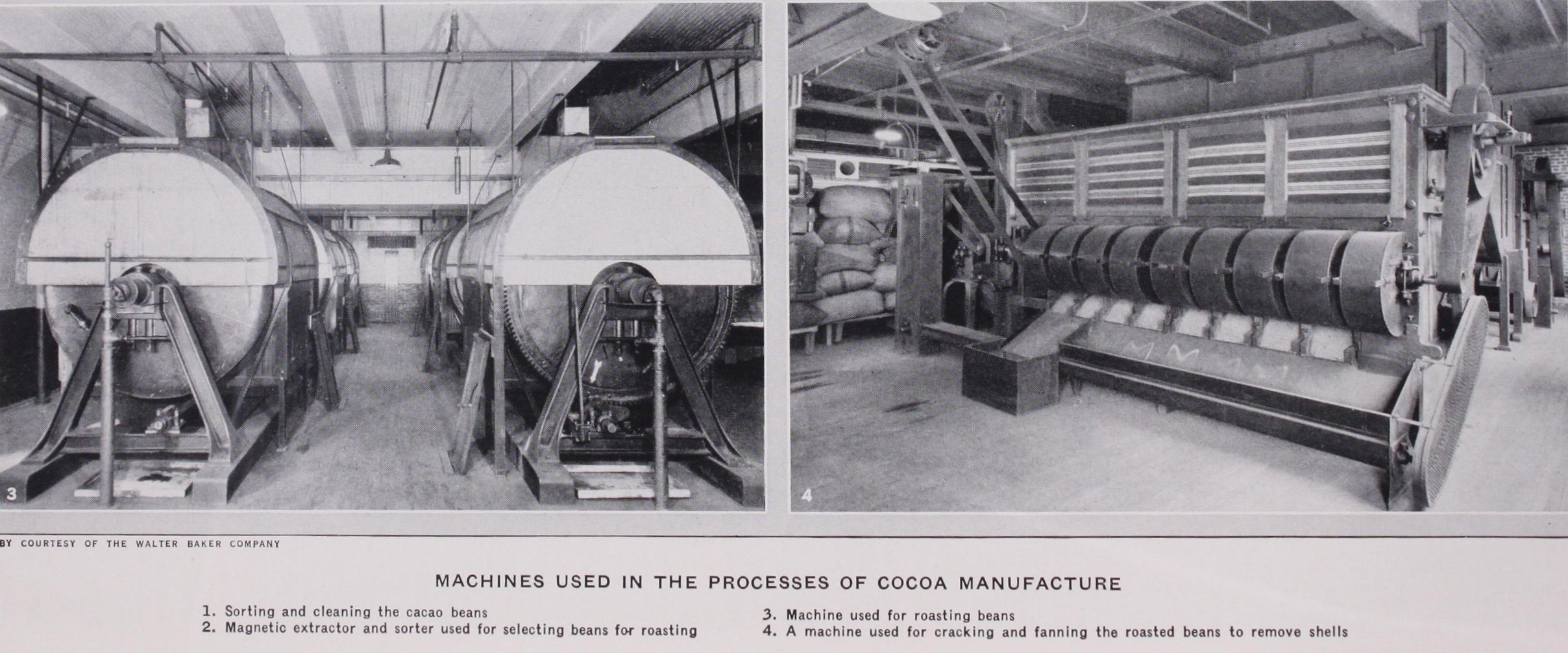

Duty on Cacao, Cacao Butter and Cacao Shell (Imported in Great Britain, Cacao beans, if roasted and crushed in the palm of the hand, produce the fragrant odour of chocolate and are broken up into brown, crisp, angular fragments which are termed "nibs." It is a simple matter to blow away the thin flakes of the husk, or shell, without losing the nib. The nib contains 54-55% of cacao butter, and if simply ground with sugar, gives with hot water a very fatty beverage which for over i oo years has been served out to the British navy. To produce a less rich beverage two methods have been adopted. The first is the addition of corn-flour or arrow root. Such mixtures cannot in most countries legally be described as pure cocoa. The second is the removal of part of the cacao butter by pressure. This is the usual method, and cocoa may be defined as the finely ground cacao nib from which part of the cacao butter has been removed. The factory operations are as follows :— The clean sorted beans pass along a conveyor to the roasting machines. Roasting is a delicate operation requiring experience and discretion, and is usually conducted in revolving drums heated externally by gas. The temperatures used are lower than for coffee roasting, and seldom exceed i4o°C. The roasted beans pass between rolls of serrated cones, which are placed at such a distance apart that the beans are cracked rather than crushed. The frag ments are sieved into fractions, from which the shell is carried off by an air blast. There is 12% of shell on the beans and this voluminous by-product was sold during the war at high prices for making "cocoa tea"; its chief use in normal times is as an appe tiser in compound cattle cakes, although a certain amount may be found in inferior cocoas.

The nibs are ground either be tween mill stones or steel rolls.

As half the cacao bean is but ter, and grinding generates heat, the crisp, nutty cacao nib emerges as a thick chocolate brown fluid. (If cooled this solidifies to a hard block and is known as unsweetened choc olate or cacao "mass.") The cacao fluid is run into circular steel pots, and hydraulic pres sure up to 6,000 lb. to the sq.in. is applied. The cacao butter which is squeezed out is filtered and solidified. The hard, dry cake of compressed cocoa, containing 20 to 3o% of cacao butter, is re moved from the pot, ground and sieved. Many cocoas receive a special treatment in addition to the above, and are known com mercially, though somewhat inaccurately, as "soluble." The proc ess, in its original form, was invented by C. J. van Houten in 1828. It consists of treating the cacao nib or mass with a small percentage of potassium carbonate, bicarbonate or other salt of the alkalies. The alkaline salt reacts with the astringent con stituents and partly neutralizes the natural acidity of the cacao. This is considered to improve the cocoa, which becomes darker in colour and less liable to sink to the bottom of the cup.

Cocoa has a high food value, and is mildly stimulating owing to the presence of theobromine (2.2%) and caffeine (o• i %) . Dr. R. H. A. Plimmer's Analyses and Energy Values of Foods (1921) for use by His Majesty's Services gives the following mean analyses of six cocoas: Fat (cacao butter) 26.8%, carbohydrates protein 18.1%, fibre 3.7%, ash 6.3%, water 4.9%; and the energy value as 2,214.5 cal ories per pound.

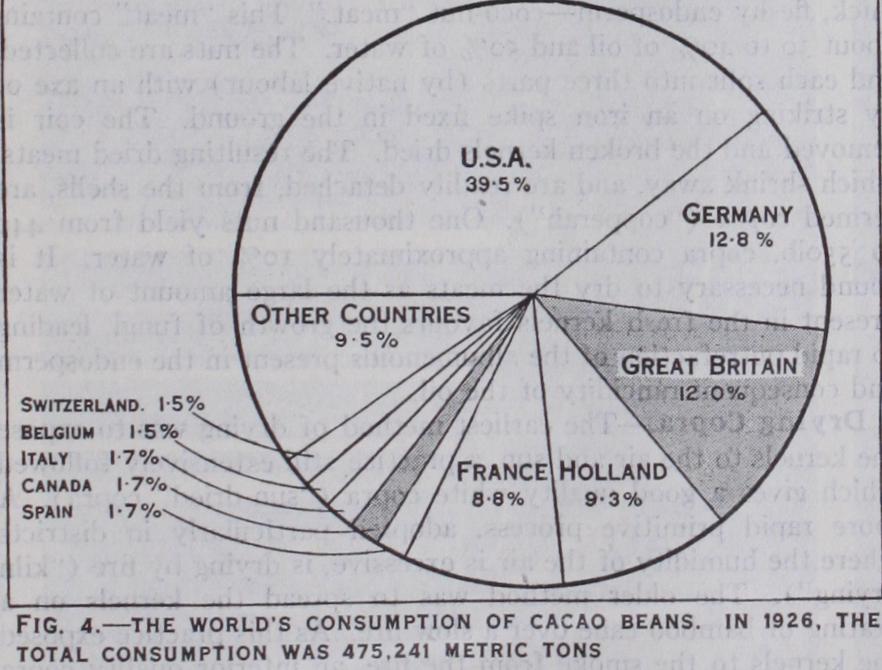

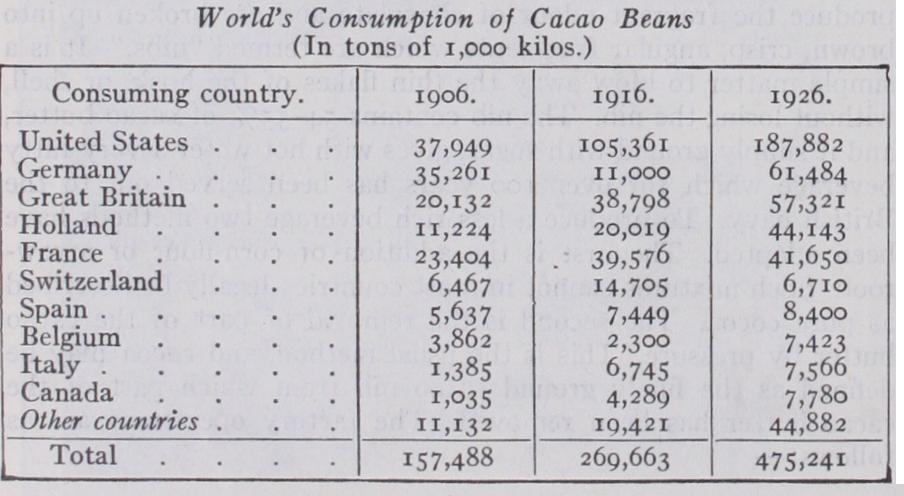

Cocoa Consumption.—Whilst the world's appetite for cacao preparations h a s continually grown, the war was responsible for a special increase. In the Uni ted States the increase has also been influenced by the absence of import duty. The chart below il lustrates the relative consumption in various countries in 1926, whilst the table shows the changes in consumption between 1906 and 1926:— Over 90% of the raw cacao consumed in Great Britain in 1926 was grown in the British empire.

For bibliography, history and production of manufactured products see CHOCOLATE. (A. W. KN.)