China - Ethnology

CHINA - ETHNOLOGY.

Although man probably existed in China before or at the be ginning of the deposition of the loess (see ASIA, section Anthro pology) there is at present no certain evidence of palaeolithic man in China. Two specimens have been found which have been considered to point to early man. A sacrum, undoubtedly human, was found in Honan, and described by Matsumoto, who failed to realize that its characters were rather akin to those of the mod ern Chinese. In 1921 Dr. Andersson discovered in a rich f ossilif erous deposit at Chou Kou Tien, south-west of Peking, a number of specimens including a premolar and a molar tooth. Black considers these to resemble in general form a fossil molar or "dragon's tooth" bought in Peking by a German palaeontolo gist called Schlosser. Fossil bones ground to powder are much used as medicine by Chinese and no data appear to be forth coming as to the origin of Schlosser's specimen. While Black is convinced that the teeth represent "archaic hominid fossil ma terial," other palaeontologists are less certain and the matter still awaits definite confirmation.

Apart from these doubtful specimens nothing of remote an tiquity has been found in China. The earliest discoveries by the people themselves of whom there is definite knowledge are asso ciated with the chalcolithic culture, and although differing in some respects from modern Chinese, are of essentially the same racial stock. Traditionally the Chinese are said to have come from the Tarim basin and to have spread down the valley of the Wei Ho into the great plain. Their extension into southern China is a matter of recent history and is still proceeding. While the cul tural evidence for this extension seems to be satisfactory, the racial characters of the chalcolithic skeletons make it possible that the Chinese claim to have come from outside China and to have driven out the barbarians, some of whom still lingered even in Honan until recent times, may not be so true racially as it is culturally. In any case the oldest culture known in China, and it probably is not of a very early date, shows affinities with the West, while the people living in China at that time were like the Chinese today; on the other hand the Mongols, whose culture is entirely alien to the Chinese, are physically akin to the peoples of the West.

The true home of the Chinese, whatever their original centre of dispersion, seems to be the basin of the lower Hwang Ha; but they have dominated, racially and culturally, both the original 18 provinces, and Manchuria, Korea, and to some degree Japan. There seem to be two physical types, a northern and a southern, though the differences between them are not very great, the north erners being generally somewhat taller.

These northerners themselves probably consist of a blend of two minor types, one akin to the Khams Tibetan—tall, long headed, big-boned, mainly proto-Nordic in origin. The second stock is similar if not identical with the southern Chinese, who are smaller and more roundheaded. They represent that branch of Yellow Man designated "Pareoean," meaning the people from beside the dawn. It is probable that there is in China a mixture of many stocks; not only have the Chinese invaded aboriginal territory and absorbed the inhabitants, but China itself has been continuously invaded especially from the north. The skin colour is generally light yellow, the hair is dark and straight. The Mon golian eyef old is conspicuous. The stature is medium and the head-form ranges from long to round; the nose is of medium width. Here and there are fair, light-eyed, wavy-haired groups, evidence of the alien stocks which have penetrated into this area.

Social Organization.

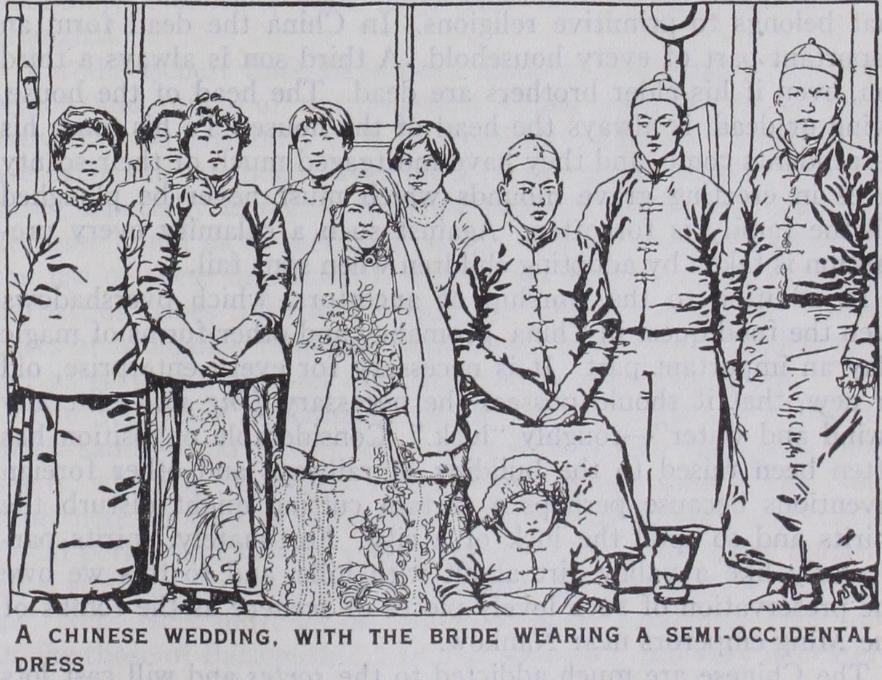

The basis of Chinese social organi zation is a closely knit and highly organized family. The house father is directly responsible for all who live under his roof, including his wife and unmarried children, his married sons and their wives and children, his servants and probably other depend ents. He is personally responsible for the economic and moral welfare of this miscellaneous group, which includes on an average between five and ten persons, and is liable legally for their mis demeanours. This system spreads upwards. The official was held to he the "father and mother" of his people, and the emperor was himself directly the head of a patriarchal family, the Chinese nation, for whose welfare and the success of the crops he was directly responsible to heaven. Much of the cohesion of China is due to this amazing social system, though it tends to exalt the family at the expense of the State. Owing to the necessities of ancestor worship the raising of male prog eny is a sacred duty of every Chinese, a fact which may account for the early mar riage and the large number of children.Polygamy is permissible, but it is naturally a luxury of the wealthy rather than a gen eral practice among the poor. Marriages are arranged by the parents of the prospec tive couple, but secondary marriages are usually "love matches." Where no sons are born the practice of adoption is used, both among rich and poor. By the rule of ex ogamy marriages were forbidden between persons bearing the same family name.

With the exception of a few families, notably the descendants of Confucius, China has no aristocracy. Position de pended entirely on success in the great examinations for literary degrees, from the successful candidates of which officials were chosen. Side by side with the official class there has always been a merchant class enjoying the advantages of wealth. The levelling effects of dependents have probably con tributed much to these democratic conditions. The higher a man pushed himself up the more numerous became his household, and it was a necessity under the old Chinese system that a magistrate should never hold office in his own province, otherwise his duties to his family would have outweighed his official duties.

Religion.

The three great religions of China are Confucian ism, Taoism and Buddhism (q.v.) . The special feature of local religion is ancestor worship, though Taoism incorporates much that belongs to primitive religions. In China the dead form an important part of every household. A third son is always a third son, even if his elder brothers are dead. The head of the house, living or dead, is always the head of the house. To his tomb his descendants come, and they have mortgaged much of their scanty acres in erecting grave mounds which must never be ploughed till the family is forgotten. Against such a calamity every pre caution is taken by adopting children when sons fail.In addition to the worship of ancestors, which overshadows even the food quest in China, geomancy and other forms of magic play an important part. It is necessary for every enterprise, old or new, that it should possess the necessary feng shui—literally "wind and water"—roughly "luck." Considerable opposition has often been raised to the building of railways and other foreign inventions because perhaps a certain cutting might disturb the spirits and so spoil the luck of a city. Fortunately, spirits par ticularly like a valley girt about with hills, and to this we owe the preservation of such lovely pieces of scenery as the tombs of the Ming emperors near Nankow.

The Chinese are much addicted to the sortes and will cast lots before undertaking any enterprise, throwing down two pieces of bamboo root till they turn up in a favourable manner.

BIBLIOGRAPHY.-S. Wells Williams, The Middle Kingdom; A. Little, Bibliography.-S. Wells Williams, The Middle Kingdom; A. Little, The Far East (19o5) ; J. Andersson and D. Black, Various papers, series D, Palaeontologica Sinica, vol. i. (1923-25) ; L. H. D. Buxton, The Peoples of Asia (1925) ; J. Mallory, China the land of Famine (1926) ; S. King, Farmers of Forty Centuries (New ed., 1927).

Aboriginal Tribes.

Chinese men of letters have classified the aborigines of China in a four-fold artificial manner, calling them by names which are more or less the equivalent of the Greek barbaros. It is probably more correct, however, to divide them into three groups, the Miao, the Lolo, and the Chung Chia. Their distribution is approximately as follows : there are Black Miao and Chung Chia in Hunan, and the city of Chung teh, near Tungting lake records the presence of aborigines in its neighbourhood. The Chung Chia extend across the border into Burma, where they are known as T'ai (q.v.). The Black Miao live north of these peoples. The two classes of Flowered Miao live in west-central Kweichow, and north-eastern Yunnan. Origi nally their distribution was probably much wider. Physically all these peoples seem to represent an intermediate type between the long-headed peoples of the Near and Middle East and the Nesiot of south-eastern Asia. They are all mixed to a greater or lesser degree with Pareoeans. Culturally they are mostly agricultural ists, but everywhere they have been much affected by the sur rounding Chinese.BIBLIOGRAPHY.-L. H. D. Buxton, The Peoples of Asia, 1925 (BibBibliography.-L. H. D. Buxton, The Peoples of Asia, 1925 (Bib- lio.) ; A. Matsumara, Cephalic Index of the Japanese, Imperial Univer sity of Tokyo, Faculty of Science (Anthropology), Tokyo, 1925.