China - Foreign Trade

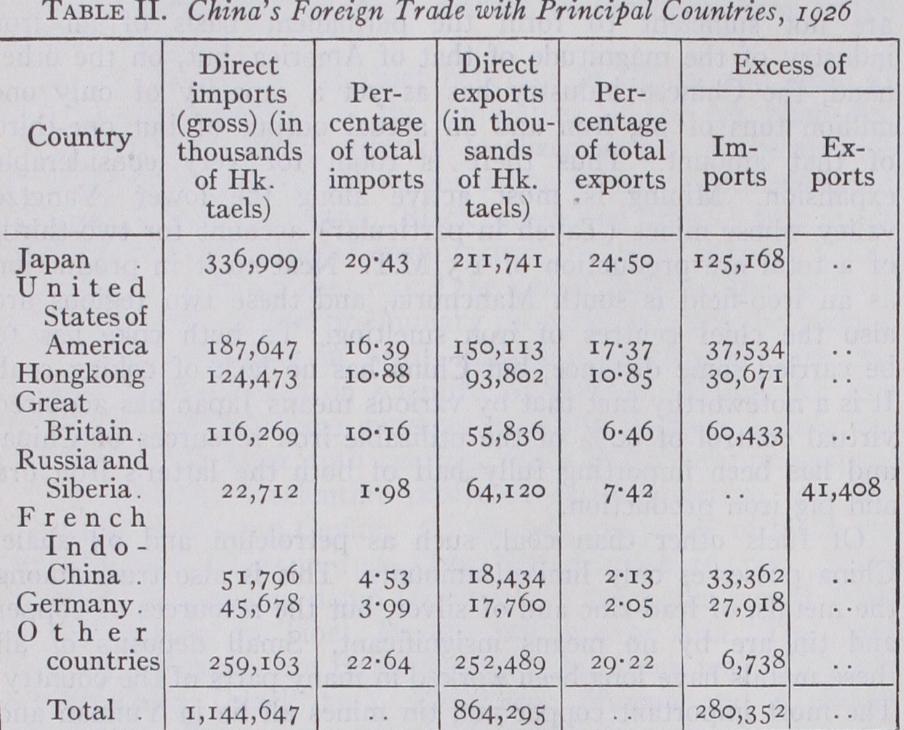

CHINA - FOREIGN TRADE The origin and characteristics of the system by which the foreign trade of China has been organized from the middle of the i9th century down to the present time (1939) are explained in the section on History. Some impending changes of great im portance are indicated below. The following tables showing the total foreign trade for 1926 according to the returns of the Chinese Maritime Customs may be taken as fairly typical of the position up to 1931 and this in spite of the disturbed political con ditions.

1. In certain respects the returns for 1926 were exceptional owing to the Cantonese boycott of Hongkong during the greater part of the year which tended to swell the returns of direct Chinese imports from other sources. In 1924 both imports from and exports to Hongkong were nearly double those of 1926.

2. The situation was altered after 1931 through the creation of Manchoukuo. Since the statistics of Manchuria, in whose trade Japan was dominant, were henceforward not included in those of China, the United States assumed the leading place in China's foreign trade, and Japan sank to second place.

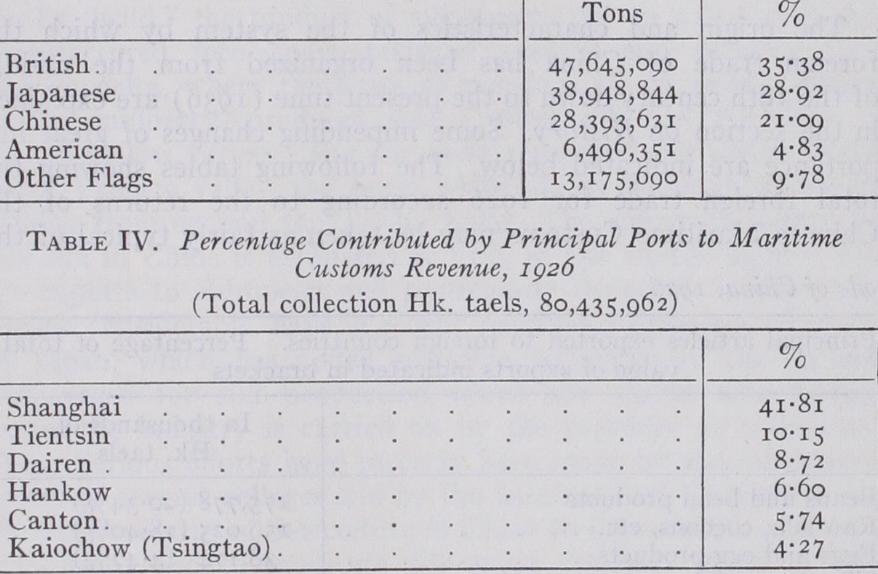

Table III. Tonnage of Vessels Engaged in Carrying Trade from and to Foreign Countries and between the Open Ports of China, 1926 Of the total shipping engaged 117,319 were steamers with an aggregate tonnage of 132,249,000 and 41,677 were sailing ves sels (almost entirely Chinese junks) with an aggregate tonnage of 2,410,00o. An important feature shown by the first two of these tables is the considerable excess of imports over exports and, with the exception of certain years in the eighties, this has been a constant characteristic of Chinese foreign trade since 1869. The interpretation of this excess is by no means easy. It cannot be explained as in the case, for example, of Great Britain, by so-called "invisible" exports in the form of shipping services paid for by imports or by interest on capital invested abroad, which again swells the import list. China has, however, an important asset, which is in some respects comparable to the latter, in the extensive remittances made to their ancestral homes by emigrants to Malaya, the Philippines, the Dutch East Indies, Indo-China, the Americas and Europe. On a calculation recently made by the Bureau of Economic Information from an estimate of the Yokohama Specie Bank for 1925 the aggregate total reaching China from this source in various forms amounts to about $16o,000,000. This certainly more than counterbalances the swelling of the export figures by the net profits of foreign resi dents in China and of foreign shipping and insurance companies. But, important as this factor is, it does not seem sufficient to cover what the official returns describe as an "unfavourable balance," reflecting the present economic position of China. To quote the Maritime Customs' report on the foreign trade of China (1926) : "one must conclude that the Chinese people are dependent on foreign countries for a very great quantity of goods which they cannot produce as yet, while their own products meet with a very strong competition by similar products from other countries in foreign markets." The heavy import of f ood stuffs in a country so predominantly agricultural is particularly significant, for it is precisely by the export of these and of raw materials that most agricultural countries pay interest on the loans made by foreign capitalists to assist their industrial develop ment. In the case of China many of these loans have been se cured on railways and other national assets, with resulting political complications, and under the most favourable circumstances a long time must elapse before China can completely free herself from the entanglements which this indebtedness involves.

After 1918 the organization of Chinese foreign trade entered on a new and momentous phase. By the Treaty of Versailles Germany surrendered her concessions at Hankow and Tientsin, and Russia, too, as a result of the World War, lost and later renounced her treaty privileges. At the Washington Conference (1921-22) the Nine Power Treaty on the Chinese customs tariff decreed inter alia "a general revision of the tariff, to make it a more effective instrument of revenue, with the authority to increase it in return for the abolition of likin." Under Resolution IV. of the Washington Conference, the Commission on Extra territoriality met in Peking in Jan. 1926 and in September of that year the representatives of 13 Powers signed the report recommending that, when certain conditions were satisfied, the Powers concerned should relinquish extraterritorial privileges, on the understanding that their nationals would then have the right to reside, trade and enjoy civil rights in all parts of China. In 1925 and 1926 an international conference was held in Peking to deal with the problem of the tariff. In 1927 both Great Bri tain and the United States promised to concede tariff autonomy and to relinquish extraterritorial rights. With the establishment of the Nationalist Government at Nanking, claiming authority throughout China, the fulfilment of these pledges was pushed. In 1928, 1929, and 193o, all the powers, including Japan, con sented to the resumption by China of tariff autonomy. In 1929 China made these agreements effective by inaugurating a system of duties fixed by herself. In Dec. 1929, China announced the termination of extraterritoriality, but by Jan. 1, 1932, later set for assuming jurisdiction over foreigners, the hostilities in Man churia had broken out and the Chinese did not carry out their purpose.

In 1927, 1929, and 193o, Great Britain surrendered several of her concessions in treaty ports. Chinese were admitted to mem bership of four of the major remaining concessions. The Shanghai Mixed Court, in which Chinese defendants were tried, was re stored to Chinese control (Jan. 1, 1927).

Transport Conditions and Communications.

For the most part freight is still moved in China, as it has always been, by human labour, with animals as supplementary carriers. The wheelbarrow and carrying-pole are the commonest means of trans port for small merchandise. In north China wheeled vehicles, mostly the springless Pekingese cart, are used to a considerable extent on the sandy tracks, while in the centre and south the sedan-chair is still in evidence, and rickshas are in general use in and around the larger cities. The Tsin-ling mountain belt roughly defines the northern limit of the general use of water transport, which in north China becomes subordinate to the cum brous cart, drawn by horse, mule, bullock or mixed team. In the utilization of inland waterways no people have excelled the Chinese. The natural routes provided by the Yangtze and its great tributaries and to a less extent by the Si-kiang and other rivers of south-east China bear an enormous amount of junk traffic, while steam boats, large and small, are increasing, especially in the Lower Yangtze. From an early stage of Chinese history the rivers have been supplemented by canals, the beginnings of the famous Grand canal, now largely derelict owing to the migration of the Yellow river, going back to the 6th century B.C. In central and south China the great bulk of inland trade is carried on by water-ways, and many millions of Chinese spend their lives in boats. At various periods of Chinese history extensive systems of "imperial" highways have been constructed, radiating from the capital, but these have seldom been kept in repair for long and now are mostly mere tracks. In recent years, however, the "good roads movement," launched at Shanghai in 192I and strongly supported by the merchant class, has made considerable progress, and round many of the more progressive cities broad macadamized thoroughfares, capable of carrying heavy traffic, are being con structed. Motor services are coming into existence, and thousands of miles of motor roads have been built. Most of these have only dirt surfaces, but some have been given rock dressings. Notable is a road which, under the pressure of military necessity, the Chinese have built from Yunnan to Burma. The displacement of human by motor transport which has already begun must involve important social consequences.The program of railway construction, which in the early years of the century was making fair progress, was almost entirely held up during the period of civil war. It was resumed in the 193o's. The outstanding feature of the railway system, so far as it has been completed, is the concentration in north China and the lower Yangtze valley. Thence diverge: (I) The Peking-Kalgan-Suiyuan-Paotowchen line (S97 m.) which ascends the scarps leading to the high Mongolian plateau and is intended to develop the pastoral and potential agricultural resources of Inner Mongolia and northwest China. This line is notable as having been constructed and maintained by the Chinese without external assistance.

(2) The two great trunk railways traversing the plain of north China from north to south. (a) The Peking-Hankow railway, whose route lies along the western border of the plain, and with the recently completed line from Wuchang (across the Yangtze from Hankow) to Canton, forming the north-south artery par excellence. (b) The Tientsin-Pukow railway running through the eastern part of the plain links Peking with the Shanghai-Nanking line and the lower Yangtze valley.

(3) The Peking-Tientsin-Mukden railway, traversing the coastal sill between the edge of the Mongolian plateau and the sea, joins the two great northern centres with the metropolis of south Manchuria and makes contact with the complex and rapidly expanding railway system of Manchuria. (See MANCHURIA.) The most important transverse line is the east-west Lung-hai railway which from the new port of Haichow in northern Kiangsu crosses both the north-south trunk lines and runs through Suchow and Kai-f eng to Honan-fu, Hsianfu, and Paochi, its present ter minus. Continuations have been projected to Lanchow, in Kansu, and to Chengtu, in Szechwan.

Apart from small branch lines, mainly tapping coal-fields, there are two important railways connecting with the main systems: the Shantung railway joining Tsinan-fu with Tsingtao (Kiao chow) and the Shansi railway linking the Peking-Hankow line with Tai-yiian-fu.

Shanghai is the focus of a distinct system:—(I) Shanghai Nanking (see above), (2) Shanghai-Hangchow-Ningpo, (3) Shanghai-Woosung (the first railway opened in China, 1876).

From Hangchow a railroad stretches westward through. Nan chang and has been projected to reach Kweiyang and Yunnan-fu.

In the south, Canton has a similar role. Apart from the Canton Wuchang line, already mentioned, short railways connect the southern metropolis with Kowloon, opposite Hongkong, and with Samshui. The only other important railway in China is the trunk line, completed by the French in 1909, which runs from Haiphong in Tong-king to Yunnan-fu in south-west China, 200 m. of its course being in Chinese territory. There are short local lines running inland from Amoy, Swatow and Macao respectively, and one connecting Kiukiang and Nanchang.

Three provinces of China Proper (Kansu, Kweichow, and Kwangsi) have no railway mileage, and several others very little. In all China (excluding Manchuria) there are less than Io,000 m. of railway, or i m. of railway to about i 5o sq.m. of territory, as compared with 4o in India, 16 in Japan, and 12 in the United States. Of the grand total the larger proportion has been subject to the control of the Ministry of Communications.

The years immediately preceding the war of 1937 witnessed extensive railway building and at the outbreak of hostilities other lines were either projected or actually under construction. In the Japanese were in possession of practically all the rail ways except the French line into Yunnan. Except in Manchuria, railway construction has ceased.

The postal service of China has been greatly improved in recent years and there are now about 12,000 post offices open and nearly I,000 telegraph offices. As a result of the Washington Conference and in acknowledgment of the efficiency of the Chinese postal service, all the foreign Powers concerned agreed to withdraw their postal agencies from China on Jan. I, 1923. Wireless is already fairly widely distributed, even as far afield as Ulan Bator Hoto (Outer Mongolia) and Kashgar (Sinkiang).

Aeroplane service has been established between a number of the main centres, and although somewhat disarranged in by hostilities, has more or less kept to regular schedules.