Chinese Architecture

CHINESE ARCHITECTURE. The art of building in China has always been closely dependent on the intimate feeling of the Chinese people for the significance and beauty of nature. They arranged their buildings with special regard to the "spirits of earth, water and air," their ambition being not to dominate nature by their creations, as Westerners mostly do, but to co-operate with it, so as to reach a perfect harmony or order of the same kind as that which is reflected in the creations of nature. It was less the outward forms that interested them than the inner meaning, the underlying creative forces. This is most evident in the arrange ment of some of the great tombs and shrines or in open-air altars dedicated to the divinities of heaven and earth. But it is also reflected in profane buildings such as the imperial palaces, which were planned and built according to sidereal or cosmological con siderations. This appears even from the name used for the present and some earlier imperial palaces : Tzu Chin Ch'eng, the so-called Purple (or Violet) Forbidden City, of astronomical origin : the Heavenly Lord or Ruler Above was supposed to occupy a polar constellation composed of 15 stars called the Purple tected Enclosure, and as this was situated in the centre of the celestial world, so was the palace of the emperor, the human sentative of the highest divine principle, supposed to be in the middle of the human world.

The general arrangement and planning of the Chinese buildings have indeed very little in common with such artistic points of view as have been applied in Western architecture ; they result rather from religious and philosophical ideas which have their roots in most ancient traditions. This ac counts also for the uniformity, not to say monotony, of early Chinese architecture. The principles of construction have remained the same during many centuries, as have also the plans of the temples and palaces. The modifications of style which have been intro duced are of comparatively small importance. It thus becomes pos sible to draw some conclusions from relatively late examples about the earlier buildings, which unfortunately are practically all destroyed ; the wooden material has poorly withstood the ravages of fire and warfare, and the people have never made any serious efforts to protect their old buildings. It was mainly for the dead that the Chinese created more permanent abodes, and thus the tombs are the most ancient architectural monuments still existing in China. Besides these there are some cave temples hollowed out in the mountain sides and a few stone and brick pagodas of early date which will be men tioned later.

The Walls of China.

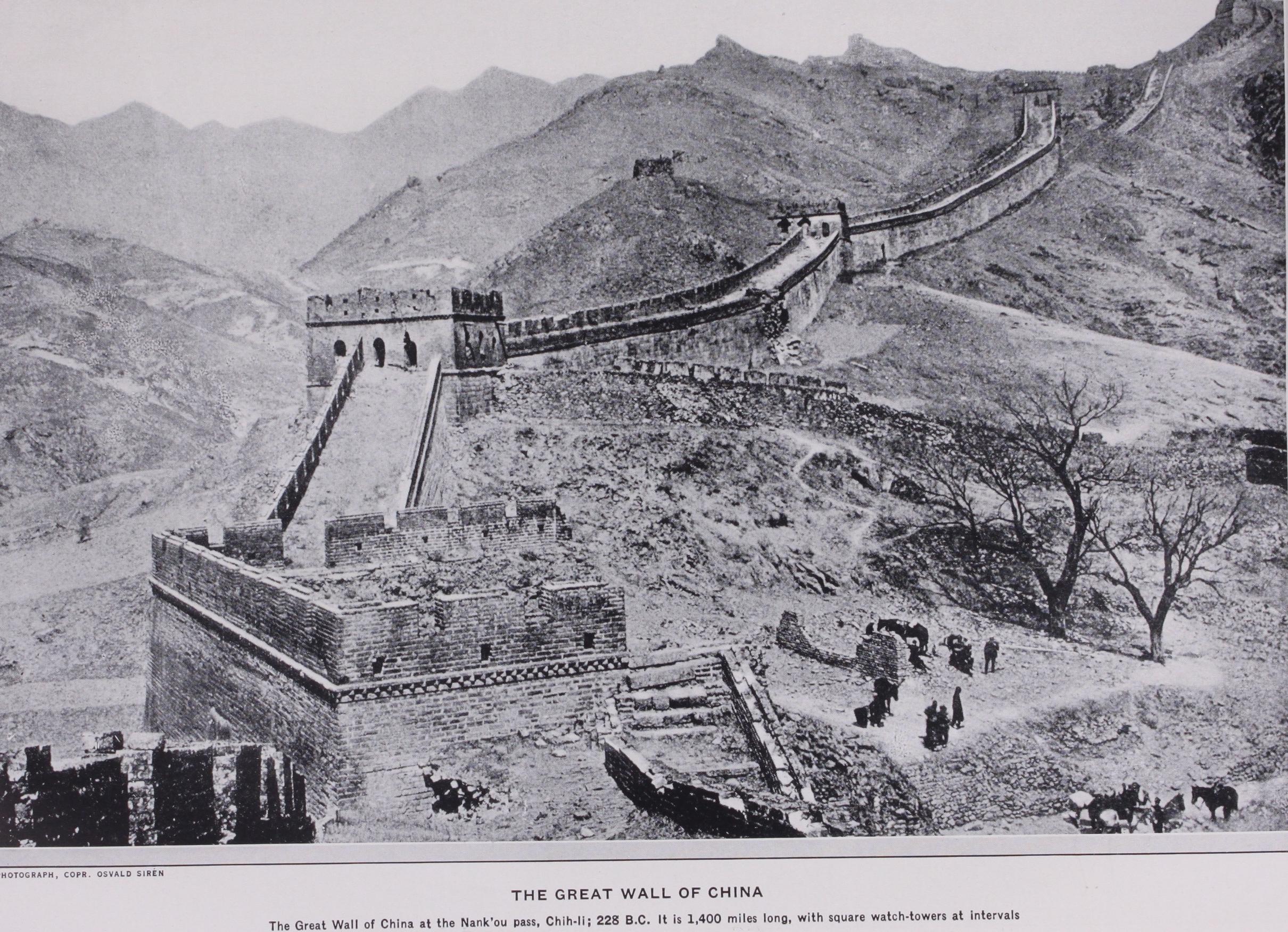

The earliest architectural monument above the soil in China is the "Great Wall," a massive fortification running along the northern and north-western frontier of the coun try. It was erected by the great Emperor Ch'in Shih Huang Ti shortly after he had reunited the different parts of the country into an empire (2 28 B.c.) . No doubt minor parts of such a wall had existed before his time, but he planned his defence against the nomadic tribes on a very much larger scale than had any previous ruler. It is stated that nearly 75okm. of the wall were built during his reign. Whatever truth this statement may contain, the fact remains that he laid the foundation of one of the world's grandest constructions, which, after many enlargements and restorations in the course of time, is still of great importance. The structural character of the wall is quite simple. It is built mainly of earth and stone, varies in height between 6 and 10 metres and is mostly covered by a coating of bricks. On the ridge of the wall runs a passage three or four metres wide between crenellated parapets, and at regular intervals square watchtowers rise above the ridge on which fires were lighted as soon as any danger was sighted. In spite of this uniformity, the wall is intimately connected with the landscape, rising in many parts almost like one of nature's own creations, accentuating the sharp ridges of the mountain chains and winding according to the undulations of the ground. It is the greatest and most monumental expression of the absolute faith of the Chinese in walls.

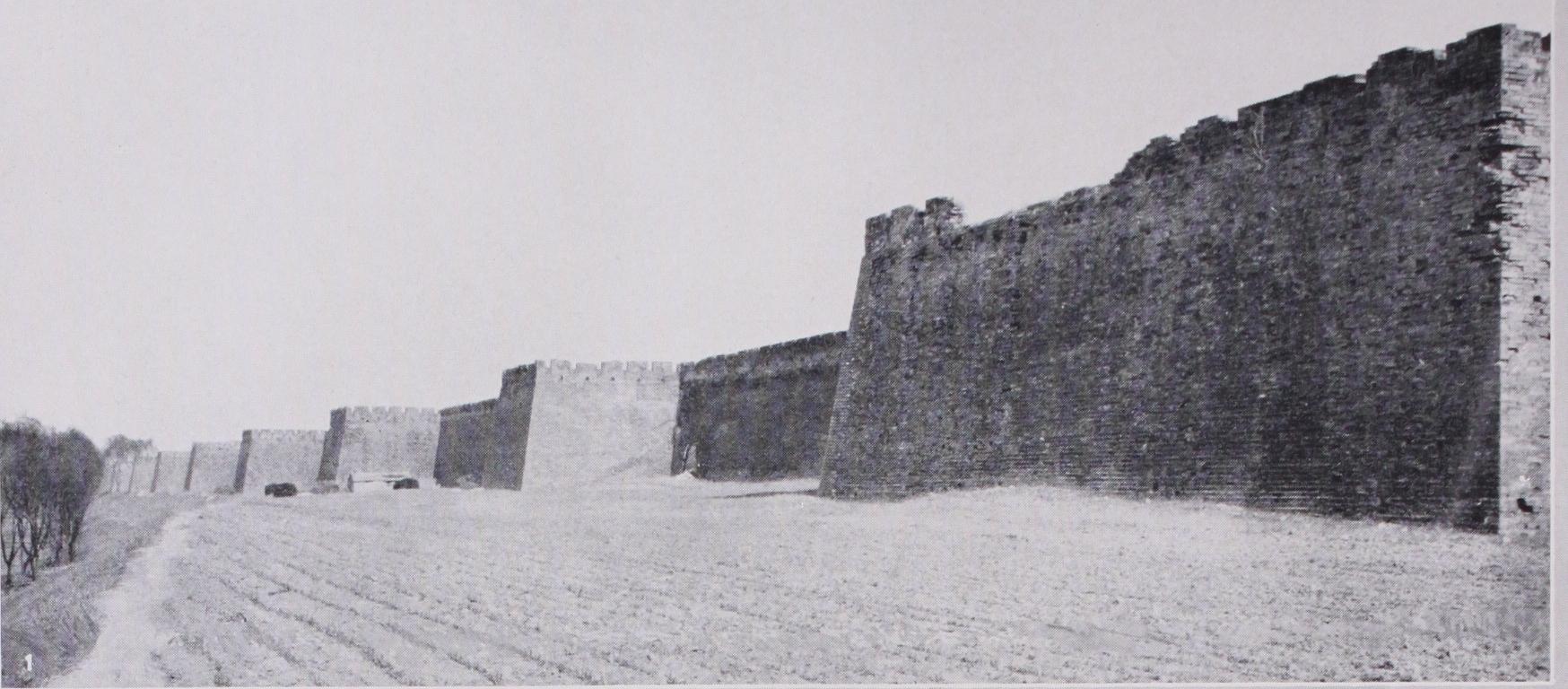

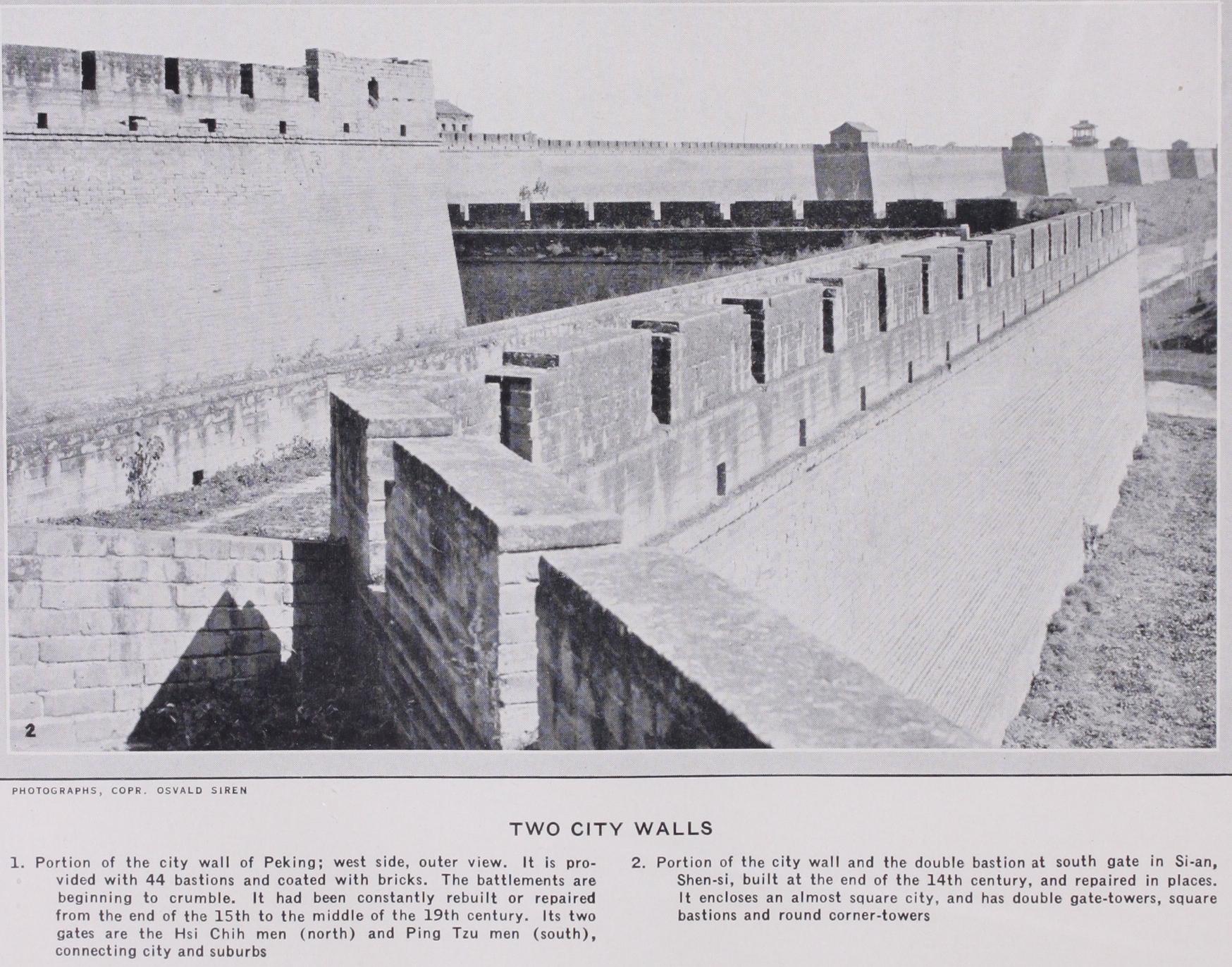

Walls, walls and yet again walls, form the framework of every Chinese city. They surround it, they divide it into lots and corn pounds, they mark more than any other structures the basic fea tures of the Chinese communities. There is no real city in China without a surrounding wall, a condition which inueed is expressed by the fact that the Chinese used the same word ch'eng for a city and a city wall ; there is no such thing as a city without a wall. It is just as inconceivable as a house without a roof. These walls belong not only to the provincial capitals or other large cities but to every community, even to small towns and villages. There is hardly a village of any age or size in northern China which has not at least a mud wall or remains of a wall around its huts and stables. No matter how poor and inconspicuous the place, how ever miserable the mud house, however useless the ruined temples, however dirty and ditch-like the sunken roads, the walls are still there and as a rule kept in better condition than any other build ing. Many a city in north-western China which has been partly demolished by wars and famine and fire and where no house is left standing and no human being lives, still retains its crenellated walls with their gates and watchtowers. These bare brick walls with bastions and towers, sometimes rising over a moat or again simply from the open level ground where the view of the far dis tance is unblocked by buildings, often tell more of the ancient greatness of the city than the houses or temples. Even when such city walls are not of a very early date (hardly any walls now standing are older than the Ming dynasty) they are nevertheless ancient-looking with their battered brickwork and broken battle ments. Repairs and rebuildings have done little to refashion them or to change their proportions. Before the brick walls there were ramparts round a good many of the cities and towns as still may be seen at some out-of-the-way places ; before the towns were built there were villages or camps of mud and straw huts sur rounded by fences or ramparts of a temporary character.

Types and Construction of Buildings.—Whether the build ings were imperial tombs, Bud dhist temples or memorial shrines dedicated to great philosophers or, on the other hand, of a pro fane nature, such as imperial pal aces, dwelling-houses or adminis tration offices, all were arranged within walls and in closed compounds according to similar principles. Characteristic of all these extensive compounds is the clear development of a main central axis running from north to south. The principal buildings, their courts and gateways are all placed in a row, one behind the other, while the secondary build ings are arranged at the sides of the courtyards, the facades, the doors and the gates of the principal buildings all facing south, an ori entation which evidently was based on religious traditions. It was not by adding to the height of the buildings but by joining more courts to the compounds that these architectural compositions could be enlarged. There are princes' palaces in Peking which have as many as 20 courtyards and some of the large temples or monasteries have a still larger number of such units. As each compound is enclosed by a high wall it is quite impossible to obtain any idea of the arrangements from the outside, and at the larger palaces the different courtyards are also divided the one from the other by secondary walls with decorative gateways. The courts vary in size and the streets follow along the walls. Through such an arrangement the inner portions of the Purple Forbidden City of Peking became almost labyrin thine.

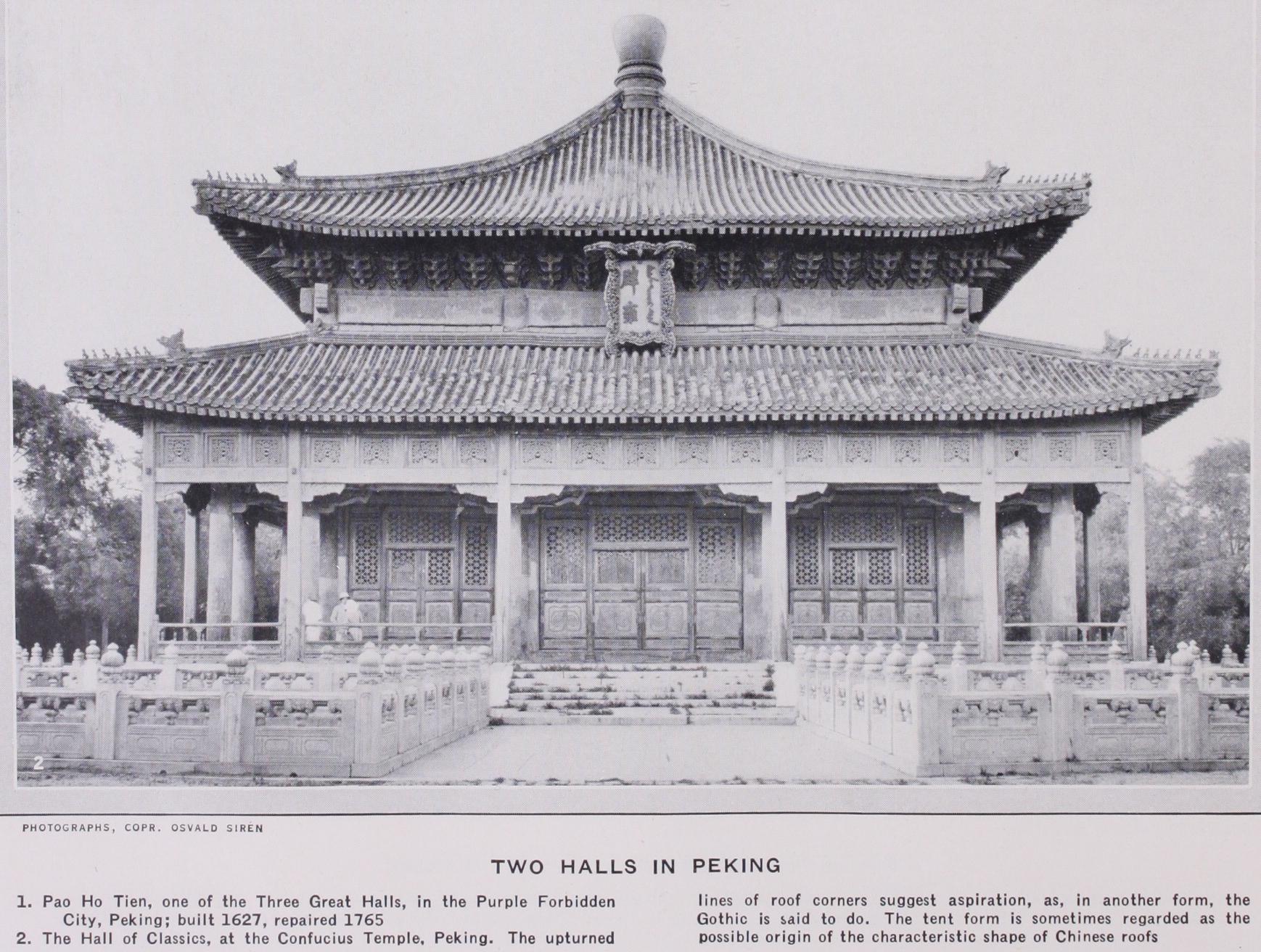

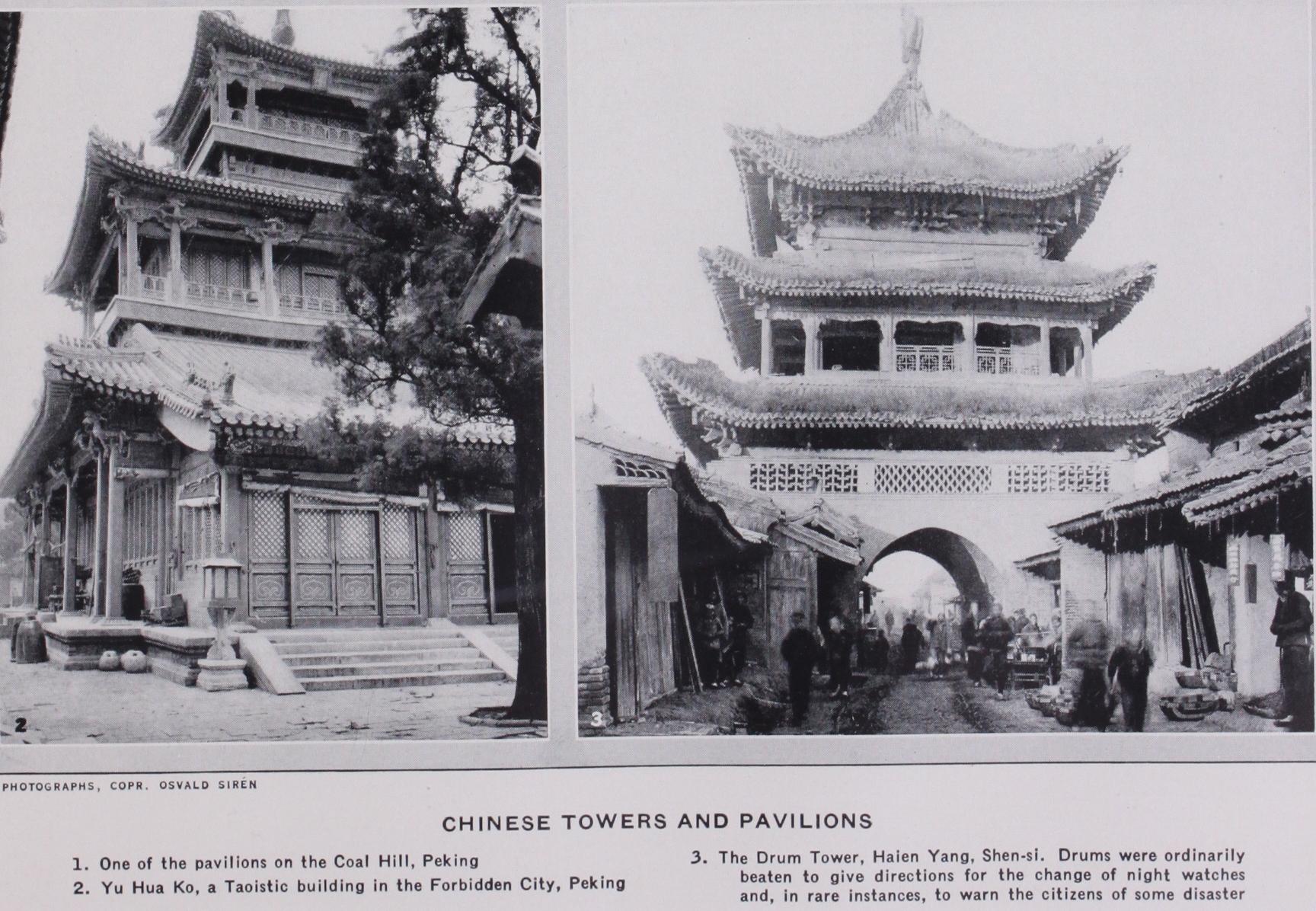

The types of the principal buildings also remain the same, inde pendently of their use as temples, palaces or dwelling-houses. The most common among these types is the hall, tien, i.e., an oblong, rectangular room, usually divided by rows of round pillars or col umns into three or more naves of which the foremost is usually arranged as an open portico ; in other cases the open colonnade is continued all around the building. The interior is, as a rule, lighted by small windows placed quite low, but exceptionally there may be a second row of windows, giving a brighter effect ; these are at a higher level. Very important for the decorative effect of the buildings is the broad substructure, the terrace and the far pro jecting roof. When the substructure is made higher, a so-called t'ai is created, i.e., a shorter hall or a centralized building in two storeys on a high terrace with battered walls. Such t'ai are of ten mentioned in the old descriptions of palaces and cities. They seem to have been quite common since earliest times. In the Forbidden City of Peking this type of building is beautifully developed at the outer gates as, for instance Wu Men, where the great pavilion rises on a monumental terrace. Other characteristic examples of t'ai are the drum and bell towers which rise in the centre of many of the old cities in northern China, but similar buildings have also been used as storehouses, watchtowers and observatories. The general name for larger, many storeyed buildings is lou, a name which, however, is not used for the pagodas, whereas small build ings of two or more storeys often are called ko, and the open small pavilions t'ing. Furthermore, one finds in some of the palatial compounds as well as at many private dwelling-houses, particularly where they are connected with gardens, so-called lang, i.e., long open galleries which serve to connect larger buildings.

Considering the most common Chinese buildings such as the tien, the t'ai and the t'ing in their entirety, we may be struck by the fact that the main body of the structures appears much less than in Western buildings. It is, figuratively speaking, pushed into the background by the broad terrace and the far projecting roof which throws a broad shadow over the facade. These two elements are of the greatest importance for the general effect of the struc ture. The terrace may be developed in various steps and provided with marble balustrades and decorative staircases, as, for instance, at the imperial palace and many large temples, or it may be simply a stone-lined substructure with one or two steps; but it always contributes to lift the building and to form a kind of counterbal ance to the projecting roof. It is, however, at the t'ai that the substructures become of greatest importance. They may reach a height of io or 12 metres and be covered by a hall or pavilion of tower-like effect.

The buildings which rise on the terraces are made of wood ; their structural frame is pure carpenters' work. The walls may look massive and appear to support the roof but, practically speaking, they have no structural importance. They are simply filled with brick or clay between the supporting columns. In the larger build ings the outer wall on the facades is usually not placed in the fore most row of columns but this is reserved as an open gallery. In some instances the portico is double, in other cases it is reduced to a few intercolumns in the middle. The building thus consists of a nave and aisles some of which might be completely or partly divided by filled-in walls, by which various rooms are created which indeed may be quite freely increased or decreased, the middle one being, as a rule, the broadest. The inter vals between the columns are on the whole quite wide, and sometimes it happens that some columns are excluded in the midst of the building in order to create more free space. But the Chinese hall is not a longitudinal structure like the Greek temples (w h i c h also originally were built of wood) ; it expands transversally to the central axis which is indicated by the entrance door on the mid dle of the facade. The two short sides with the gables serve no other purpose than to end the hall ; they have no decorative importance and no such emphasis as in the classic temples; some times they are hardly meant to be seen. The side walls may pro ject as a kind of ante-room to the portico or the corners may be accentuated by columns. The Chinese builders were never so par ticular or consistent in the placing of the columns as the classical architects. They employed a material which allowed greater free dom than the marble beams and they yielded less to purely artistic considerations than to practical wants. The beauty and strength of their architecture depend mainly on the logical clearness of the constructive framework.

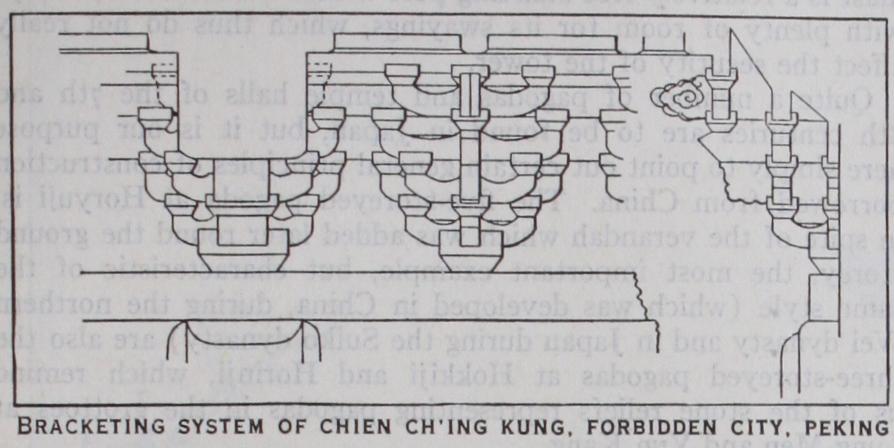

This comparative freedom in the placing of the columns is ren dered possible also by the fact that they are not supporting posts as in the classical buildings. They are not provided with capitals and they do not support the entablature, but they are tied both longitudinally and transversally by beams which may cut into, or run through, the posts. The ends of the transverse beams often project in front of the columns, and the longitudinal beams form a kind of architrave which keeps the outer colonnade together. In larger buildings of comparatively late periods brackets or canti levers are sometimes introduced on the columns below the tie beams but the real bracketing system which serves to support the eaves of the roof is situated above these. The roof brackets are, in their simplest form, two-armed and project in the earlier build ings only from the heads of the columns ; but in the later buildings they become manifolded and are placed on the beams as well as on the posts, sometimes so close together that they create the impres sion of a cornice. It is mainly in the modifications of the bracket ing system that one may trace an evolution of Chinese architec ture.

The constructive system demanded that the buildings should be developed horizontally rather than vertically. Nevertheless, many of the large halls are erected in two storeys, though the second is often nothing more than a decorative superstructure without floor or windows. The lower storey forms a kind of outer compartment to the building and is covered by a lean-to shed roof while the main span or saddle roof covers the central portion of the building which rises to a greater height. Sometimes there is a coffered or painted ceiling over this portion but more often, particularly in the tem ples, the trusses and beams of the roof construction are left entirely uncovered.

Roofs.—It is evident that the development of the roof on the Chinese buildings is closely connected with the placing of the en trance door. This is not to be found on the short (gable) ends of the building but in the middle of the southern facade, which usu ally has also a free-standing row of columns. Most of the impor tant buildings are indeed placed so that they can be appreciated only in full-front view, and their peculiar decorative effect thus becomes dominated by the broad high-towering roof. Whatever the original reason for this particular kind of roof may have been, it was gradually more and more developed from a decorative point of view. The builders may have felt the need of modifying the impression of weight and breadth, inevitably adhering to the enor mous roof masses, and this was most successfully done by curving the sides and accentuating the tension and rhythm of the rising lines. This tendency becomes perhaps more evident in minor deco rative buildings such as pavilions and pagodas, not to speak of small ornamental works in clay and metal on which the roof appears almost as a crown. The common dwelling-houses in north ern China have, on the contrary, much smaller and less curving roofs and, if we may judge from reproductions of earlier buildings, such as the reliefs from the Han tombs in Shantung and some small clay models dating from the Han and Wei dynasties, it seems that the curved roof was then not very far developed. In the T'ang time (7th to 9th century) the characteristic shape of the roof was, however, fully developed.

It is possible that the origin of the far projecting and strongly curved roof may be looked for in primitive thatch-covered huts of a kind similar to those which still are to be seen on the Indo Chinese islands. If so, it would first have been introduced in southern China (where indeed the curving and projecting roof always was more strongly developed than in the north), and later on, when the whole country became more of a cultural unit, in the northern provinces. When the Chinese once had realized the fine decorative effect of these roofs, they developed them freely at the expense of the main body of the building. The larger the roofs, the stronger becomes the effect of shade under the eaves and the more they seem to be disengaged from the supporting framework and to soar in the air. In many instances the roofs crown the building rather than cover it, and their decorative ornamentation with figures and animals on the ridges and on the corner ribs serve also to strengthen the impression of a decorative superstructure.

When the building has a roof in two storeys the lower one is a lean-to shed roof ; the upper one, a span-roof—but the gables of this do not reach down to the eaves : they are cut at one-half or three-fourths of their height. This peculiar combination of the gabled and the hipped-roof is very common both in China and in Japan, but there are also buildings with complete hip-roofs sloping to all four sides. This is, according to the Chinese, the finest form. It is to be found on ceremonial edifices such as the big central hall Tai Ho Tien in the Forbidden City, Peking, and some of the sac rificial halls at the imperial tombs.

Buildings consisting of two superimposed halls have been in use since very early days, as may be seen on some reliefs of the Han dynasty, and they are also mentioned in many of the old descrip tions of the imperial palaces, where such buildings sometimes were connected by flying bridges. Very characteristic and well-devel oped examples of this type of structure are still to be seen at Yung Ho Kung (the Yellow Temple) in Peking, which was erected in the I 7th century as an imperial residence but afterwards consecrated as a Llama temple. Later Llamaistic buildings (from the Chien Lung era) show at times an even further development in height, as for instance the Yu Hua Ko, a temple standing at the north-west ern corner of the Forbidden City. In southern China the distribu tion of storeys seems to have been still freer ; there are large tem ples in Suchow with three superimposed halls and other more cen tralized structures built in the same way, which indeed may be called towers, particularly if they are placed on terraces. The con structive framework of the main roof consists generally of various beams arranged step-wise one above the other and supporting on their ends the purlins (q.v.). In smaller buildings all the trans versal beams may be supported by columns which increase in length towards the middle of the room, the central one reaching up to the main ridge. It is, however, more common that only the low est or the two lower beams rest directly on pillars, while the upper ones are carried by brackets and small posts rising from the lower beams. The purlins laid on these supports are arranged rather closely, so that the rafters may be stretched in curves, the project ing ones being spliced and bent upwards. The well-developed sys tem of brackets and cantilevers which support this projecting part of the roof will be specially discussed later because it is in this that one may follow the development and decay of Chinese archi tecture.

The outer aspect of the roof is determined by the alternatively convex and concave tiles and the strongly accentuated corner ridges which curve at the ends in a kind of snout and often are provided with series of fantastic human and animal figures, called k'uei lung tzu. The main ridge-post is very high and decorated at both ends with a kind of fish-tailed owl, called ch'ih wen, which had a symbolic significance and served to protect the building against fire and other calamities. On ordinary buildings the roof tiles are of unglazed, lightly baked grey clay, but on the present imperial buildings all the roofs are laid with yellow glazed tiles, while some of the temples and smaller buildings erected for various members of the imperial family have deep-blue roof tiles. Green tiles are sometimes used on pavilions, gates and walls.

The columns as well as the filled-in walls between them have usually a warm vermilion tone which becomes most beautiful when softened by dampness and dust. The beams and the brackets below the eaves are painted with conventionalized flower orna ments in blue and green, sometimes with white contours. The door panels of more important buildings are provided with ornaments in gold, but their upper part serves as windows and is fitted only with open lattice-work. On the whole it seems as if later times had tried to gain by decorative elaboration whatever of constructive signif icance and beauty had been lost.

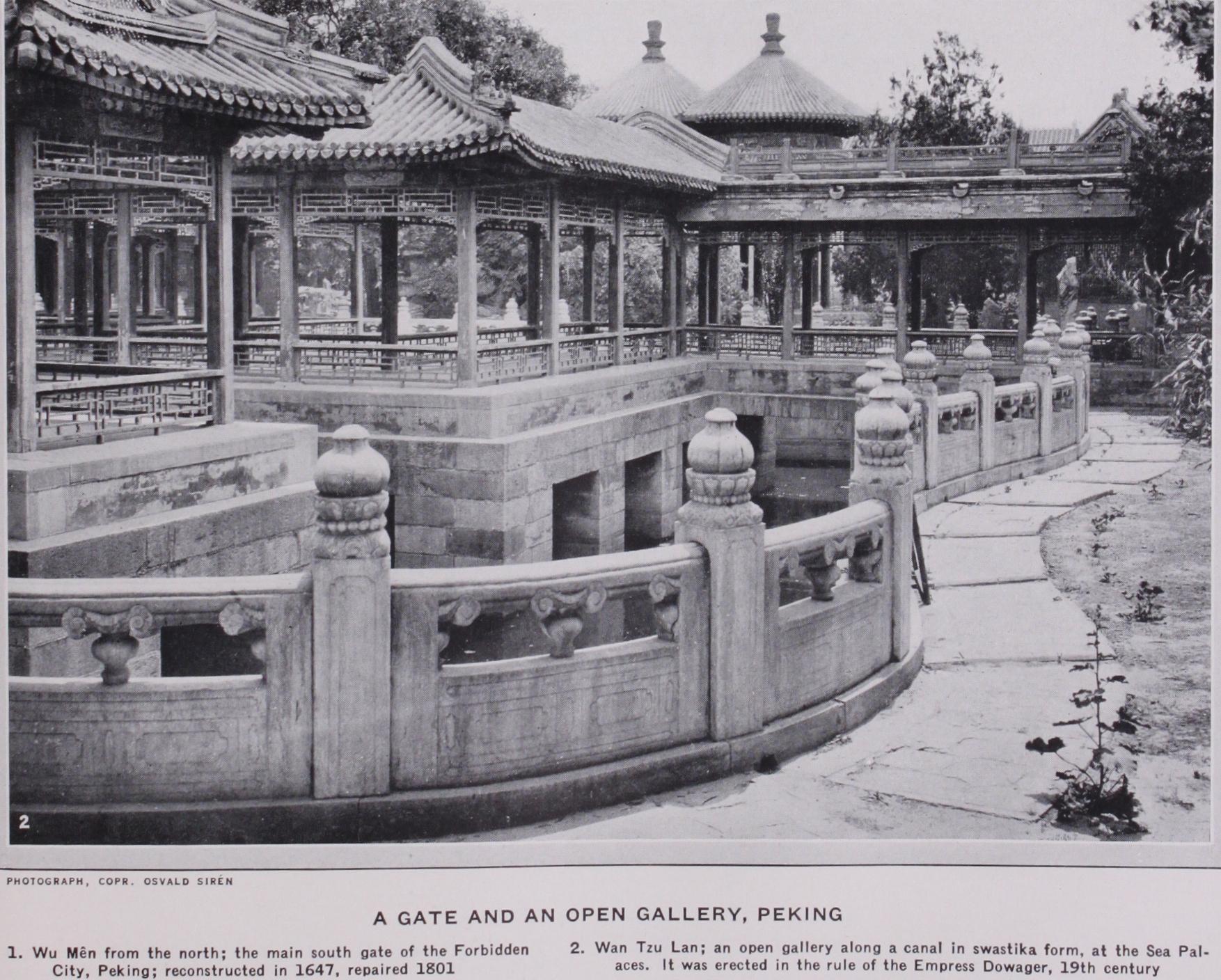

Minor Pavilions and Gateways.—Besides the longitudinal halls in right angle to the central axis, indicated by the entrance door, there are more centralized structures on a quadrangular, polygonal or round plan, i.e., pavilions or towers, which may be more than two storeys high. The most primitive type of pavilion is a square hut with corner posts which carry a flat or tent-shaped roof. Such pavilions are often seen in pictures representing famous philoso phers meditating on nature. Unless they are quite open the walls may be made of bamboo or basketwork. The more elaborate pa vilions on a polygonal or round plan developed in connection with the Chinese garden and have been abundantly used in the imperial parks since early times. Such kiosks, tea-houses and pavilions were placed on spots with historical associations or on hills or promon tories where the view was particularly beautiful. Their shape and style were developed with a view to the rockeries and the growing trees; how well they fitted into such surroundings may still be seen in the wonderful gardens around the sea palaces in Peking. These small pavilions, half hidden between the trees, clinging on the rocks or rising on stones out of the mirroring water, often give us a more vivid and immediate impression of the charm and natural ness of Chinese architecture than the larger buildings. It was also pre-eminently through such small decorative structures that Chi nese architecture became known and appreciated in the i8th century in Europe.

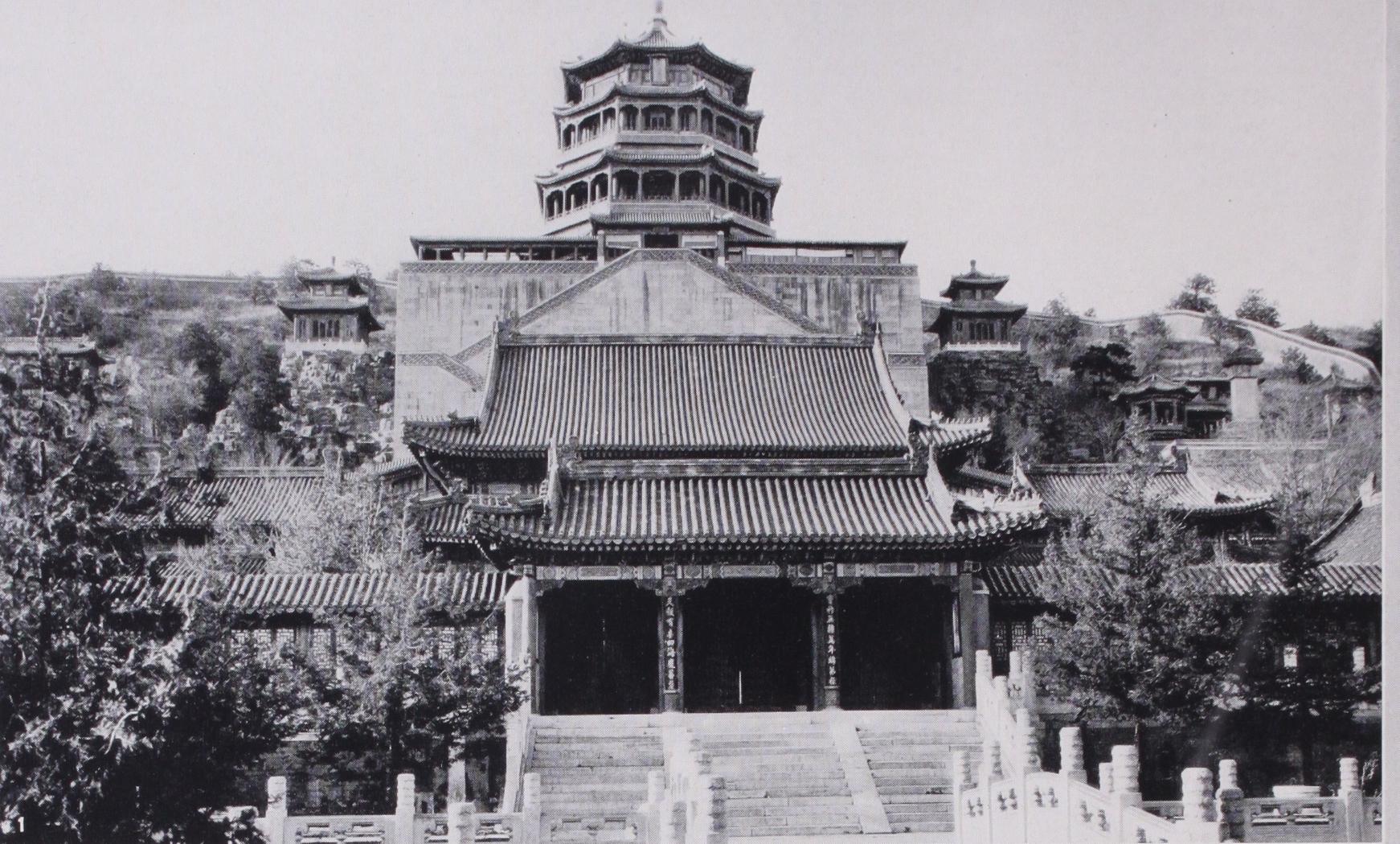

On the larger pavilions the roofs are usually divided into two or three storeys, thus adding greatly to the picturesque effect of the building, particularly when it is erected on a polygonal plan which gives it a number of projecting corner snouts. Beautiful examples of this kind of pavilion may be seen at the "Coal Hill" in Peking as well as in Pei Hai and other imperial parks. They have no walls, simply open colonnades supporting the roof which may give the impression of hovering in the air. When the portions between the successive roofs are enlarged and provided with bal conies or colonnades the pavilion becomes a real tower, such as for instance the Fo Hsiang Ko (Buddha's Perfume Tower), which rises above the lake at the Summer palace.

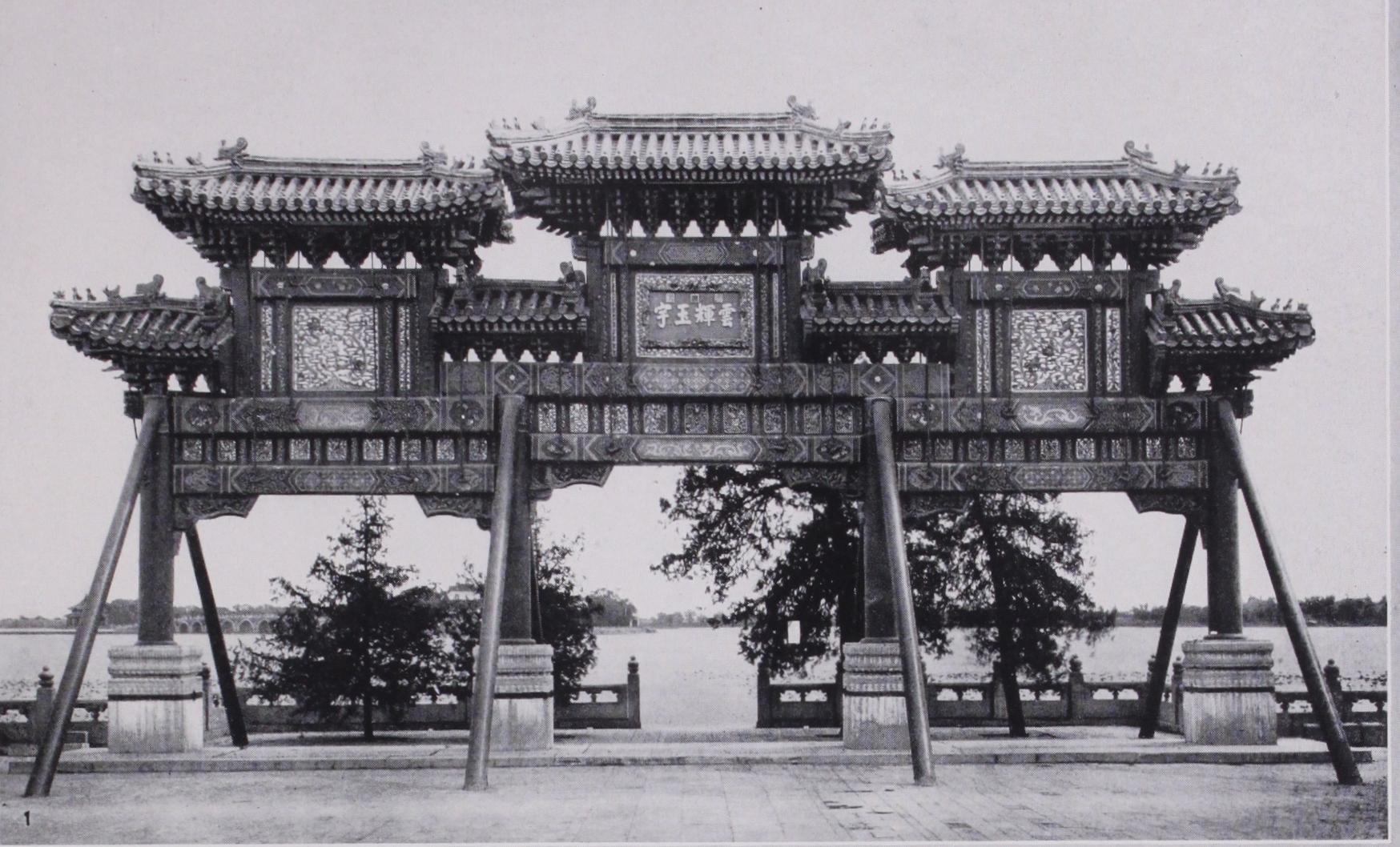

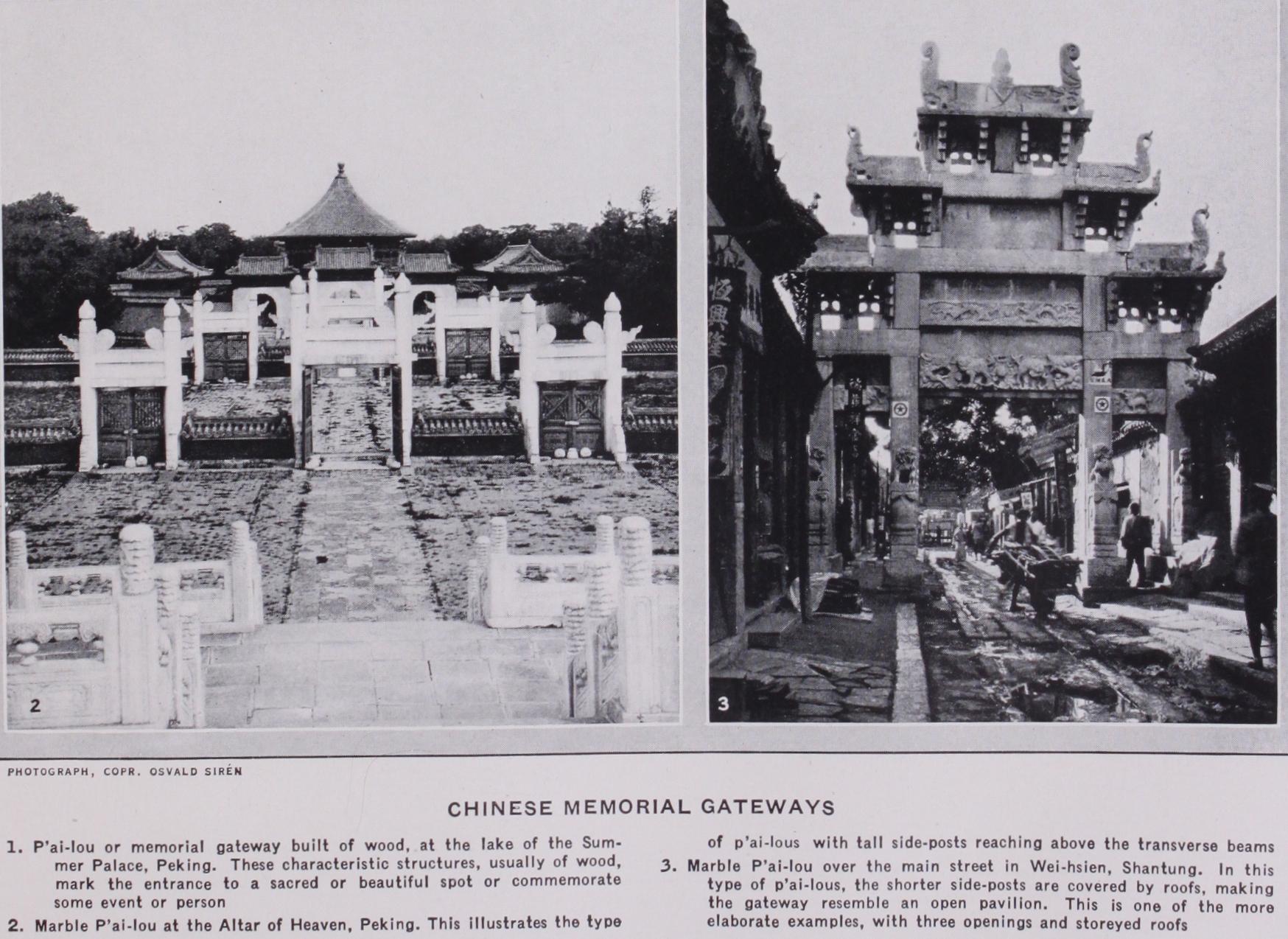

Related to the pavilions by their open decorative effect, yet forming an architectural group of their own, are the p'ai lou, i.e., free-standing gateways with three or more openings, which span the streets in many Chinese cities or mark the entrance to some sacred precincts, such as tomb or temple areas. The object of their erection was often to commemorate some outstanding local character or some important event in the history of the place or simply to mark a spot notable for its beauty or its sacredness. The earliest p'ai lou were, no doubt, simply large gateways made of wood and provided with inscribed tablets. These could easily be developed into more important structures by adding at the sides more posts and gateways, and they were soon executed in stone as well as in wood. From an architectural point of view they may be divided into two principal groups : the one consisting of p'ai lou with very tall side posts reaching above the transversal beams (which may be covered by small roofs) ; the other, of p'ai lou with shorter side posts covered by the roofs, so that the whole gateway has more likeness to a facade or an open flat pavilion. The supporting masts, which may be 4 or 8 or t 2 according to the size and importance of the structure, are placed on stone plinths, sometimes decorated with lions, and tied together not only by cross-beams in two or three horizontal rows, but also by carved or painted panels or, in the case of stone p'ai lou, by flat slabs deco rated with reliefs. Over each one of the openings is a separate small span-roof resting on brackets and usually covered with glazed pan tiles. The p'ai lou thus contain some of the most characteristic features of traditional Chinese architecture, viz., the supporting posts, the curving saddle-roofs on double or triple rows of brack ets, and the carved or painted friezes. They are essentially wooden structures. The whole character of these buildings as well as their decoration has been developed with a view to the special require ments of the material, but that has not prevented the Chinese from executing the same type of structure also in brick and in stone. The largest among them stand at the Ming tombs near Nankow and at the tombs of the Ch'ing emperors at Hsi Ling and Tung Ling, but the most elaborately decorated marble p'ai lou may be seen in some of the old cities in Shantung, such as Chufu and Weihsien.

Closely connected with the p'ai lou are those highly decorative sham facades which used to be erected in front of important shops. They also consist of tall masts tied by cross-beams with manifold rows of brackets which support small roofs in one or two storeys.

Under these are panels decorated with human figures in relief or with brightly coloured floral designs in open-work into which the signboards of the shops are inserted. High masts or pillars are indeed much in favour in China ; they are mostly used pair-wise, either free-standing in front of palaces (as the hua piao) or at the gateways of the dwelling compounds. Another type of gateway which is quite common consists of broad pillars made of masonry and coated with glazed tiles, often with ornaments in various col ours. When a span-roof connects the deep pillars a kind of small gatehouse may be created.

Of considerable importance also for the outward effect of the Chinese buildings are the balustrades which line the terraces and staircases in front of the buildings. They are in northern China mostly made of white marble and composed of square posts ending in sculptured finials between which ornamented panels and mould ed railings are inserted. Such marble balustrades may be seen at most of the important temples and, in their richest development, on the terraces of the Three Great Halls (San Ta Tien) in the Forbidden City in Peking. Here they are repeated in three differ ent tiers and broken in many angles, according to the shape of the terraces, producing a splendid decorative effect, particularly as the white marble stands out in contrast to the red colour of the build ings.

Stone and Brick Buildings.

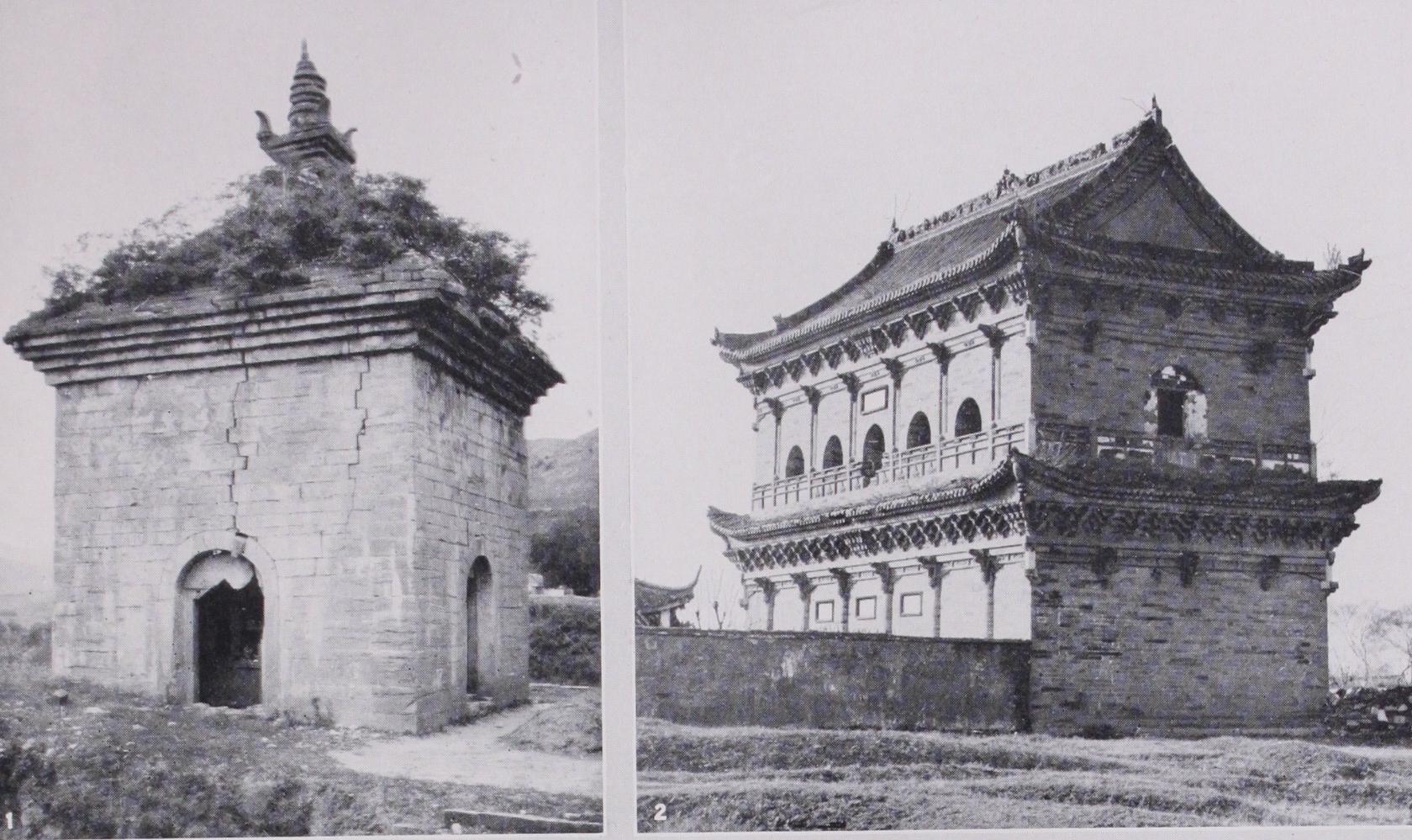

Although Chinese architecture is principally wood construction, it should not be forgotten that a great number of stone and brick buildings have been made in China, including bridges, for which the Chinese since earliest times have used brick and stone. The great majority of the still existing buildings in masonry are of comparatively late periods ; very few indeed can be dated before the Wan Li era 0573-1619). The only important exceptions to this general rule are the pagodas made of brick and mud, several of which may be ascribed to the T'ang period (618-907) and a few to even earlier times. On the whole, it seems, however, that the Chinese regarded brick and stone work as material fitted for storehouses, walls, substructures and the like, but hardly for real architecture in the same sense as wood con struction. It is a characteristic fact that brick buildings are not even mentioned in the standard work on architecture which was published by imperial order in the year 1103 under the title Ying Tsao Fa Shih (The Method of Architecture) . This beautifully illustrated work in eight volumes (which has been issued in a modem reprint) is founded on the practical experience of archi tects and decorators, which the author, Li Chieh, collected from various sources. It gives everything that an educated Chinese towards the end of the Sung period considered the fundamentals of architecture. No stone or brick houses are mentioned, not even columns, door-frames or floors of stone. The only stoneworks par ticularly described are the plinths and corner pilasters, stairs, bal ustrades, dragon heads on staircases, thresholds and stones for the door-posts, besides canals, sluices, platforms, terraces, etc. The measures and instructions for the execution of all these various kinds of stonework are very accurate, but they are of no great importance for the architectural style. The constructive methods are treated only in the third part of the book, which contains "Rules for large work in wood," i.e., framework of buildings, posts, trusses, rafters, etc. Then follows a chapter called "Rules for smaller works in wood," i.e., doors, windows, partition walls, coffered ceilings, screens, cornices, gutters, staircases, door-panels, balustrades, besides Buddhist and Taoist house shrines, or Fa yueh, decorative gate-facades erected in front of important houses, etc. Then follow "Rules for works in carved wood," concern ing decorative details, and at the end of the book, "Rules for exterior roofing," also concerning the ornamental figures on the roofs, etc. The author devotes some paragraphs to bricks and to roof tiles but he gives no rules for construction in such materials.Turning to the existing monuments in China, we may notice the Ssu Men Ta, at the temple Shen Tung Ssu in Shantung, as the ear liest and most important example of architectural masonry work. The building, which in spite of its name—the Four-Gate pagoda— is no tower but a one-storeyed square house (each side about 7.35 metres), was erected A.D. 534. It is coated with finely cut and fluted limestone slabs, but the interior body of the walls may be partly of mud. It has an arched entrance on each side and a cor nice consisting of five corbelled tiers but no other architectural divisions. The pyramidal roof is made of corbelled stone slabs and supported by a large square centre pillar crowned by a small stupa. The solid and self-contained aspect of the building together with its fine proportions make it one of the most remarkable of Chinese architectural monuments. It is possible that similar build ings existed in earlier times when stone and brick may have been more freely used ; the type may be observed, for instance, in the more or less house-shaped tomb pillars of the Han dynasty in Szechuan and Honan.

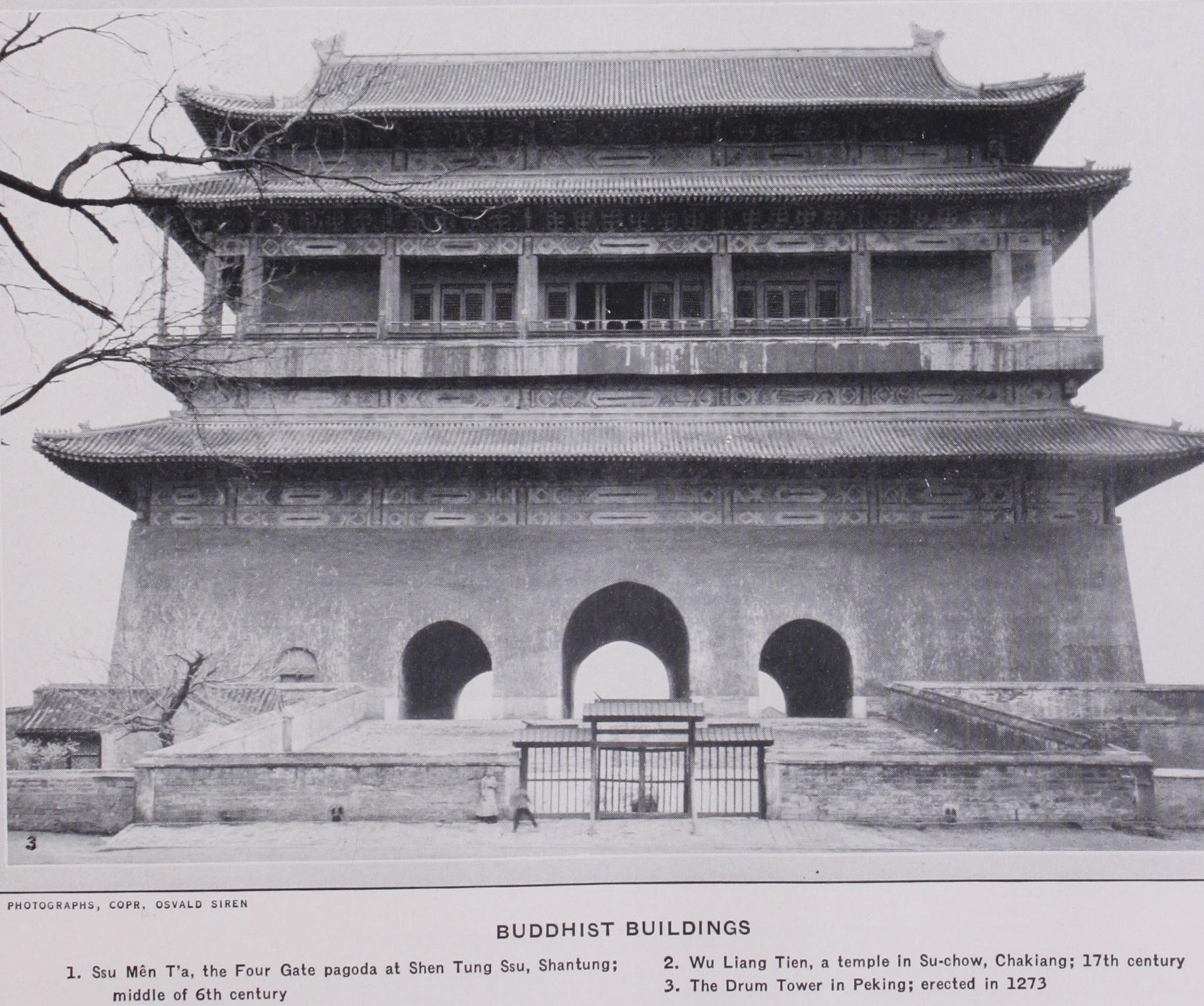

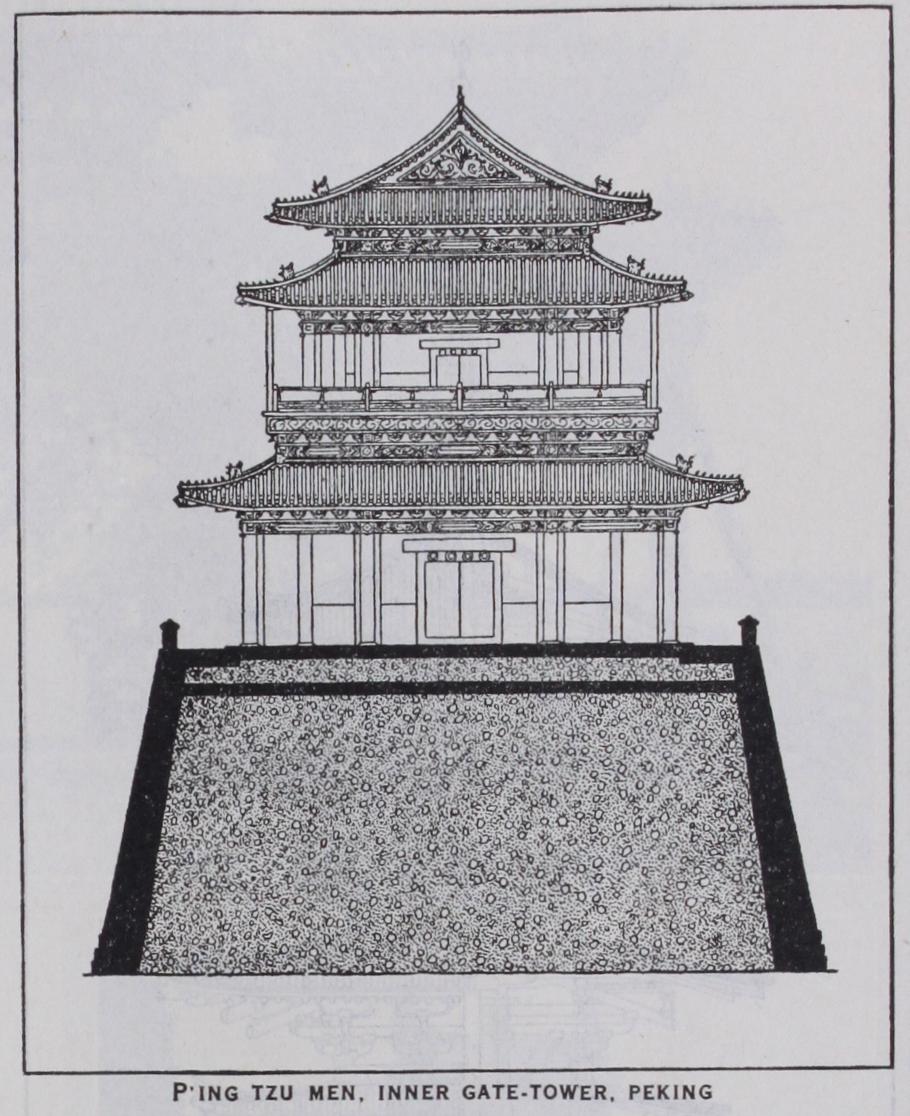

The next in date among the masonry buildings are some real towers or pagodas of the Sui and T'ang periods which will be men tioned later ; most of them are made of packed clay or dirt in com bination with stone or brick. Still more common is the combina tion of brick and wood construction. It can be carried out in dif ferent ways, either by lining a real wooden structure with brick walls or by placing a bracketed span-roof on strong brick walls, eventually adding pillars for interior support if the walls are too wide apart. This method of construction has been used in most of the outer city gate-towers, of which the oldest now preserved are from the beginning of the Ming period, and also in numerous watchtowers and storehouses on the walls that enclose the cities of northern China. A particularly fine example is the famous bell tower at Peking, often considered as a monument of the Yuan dynasty, though it was completely renewed during the reign of Chi'en Lung. All these buildings exhibit on the outside massive brick walls more or less regularly divided by windows or by rows of square loopholes which give to the battered facades of the big gate-towers a fortress-like appearance. The shape of the high roofs is, however, the same as on ordinary wooden structures, and if one examines these masonry buildings more closely, one usually finds wooden columns inserted in the walls as well as detached in the interiors.

The substructures of the gate and bell towers are in most cases pierced by tunnels or barrel vaults serving as passages. These may be either round or somewhat pointed, as for instance on the drum tower in Peking which actually dates from the Yuan period. The vaults are constructed with great care and precision, sometimes reaching a span of nearly 15 metres. Vaulting (but not the system of voussoirs) was undoubtedly known in China in early times; it was used in the tomb chambers which were covered with bricks, in the tunnels leading to these ; when heavy brick walls were erected around the cities, barrel vaults followed suit for the entrances. The step from such constructions in brick to the build ing of cupolas is not a very long one. We do not know exactly when cupolas first came into use, but we have reason to assume that they were well developed in the T'ang period. As an evidence of this the mosque in Hangchow may be mentioned because the farthest rooms of this building are covered by three cupolas on pendentives (q.v.). The mosque may have been renewed in later times but in close adherence to the original model which, of course, was of Persian origin. Another kind of cupola is to be found over the hall of the big bronze elephant on the Omi mountain in Szechuan erected during the reign of Wan Li (15 73-1619) . The transition of the square room into a round cupola is here also accomplished by means of pendentives but outwardly the building is covered by a tent-shaped roof. One of the small sanctuaries on Piao shan near Tsinanfu is an example of a more pointed cupola.

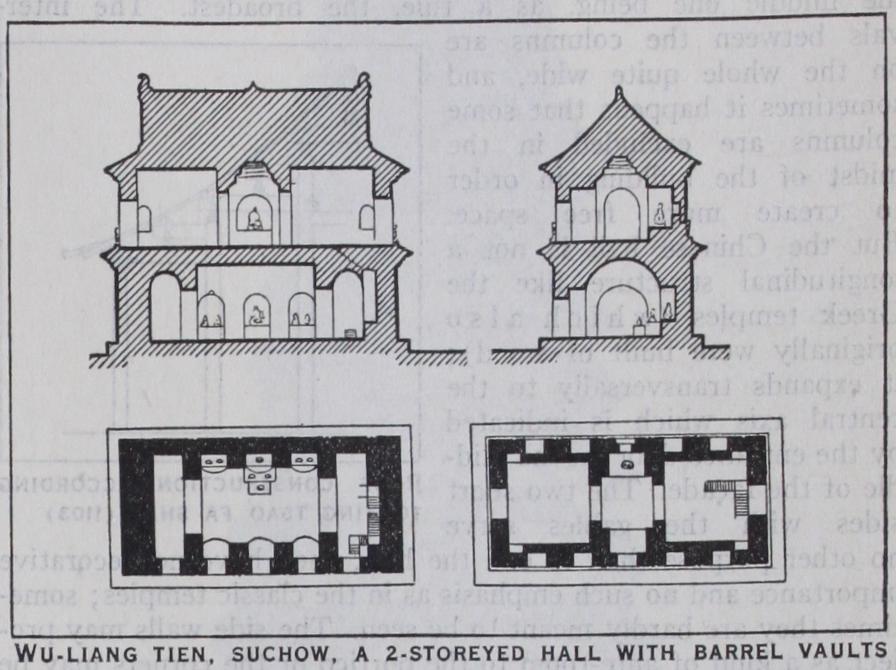

At the end of the Ming period buildings with classical orders in one or two storeys began to appear. Internally these were covered by longitudinal or transversal barrel vaults, but out wardly they were provided with the usual span and shed-roofs. Among the best examples of this kind of building may be men tioned the Wu Liang Tien in Suchow and Shuan Ta Ssu in Tai yuanfu, besides the two halls on Wu Tai Shan. The facades are divided by arches and columns, but these are partly inserted in the wall and the capitals are stunted or turned into cantilevers, the entablature reduced to an architrave, the cornice replaced by rows of brackets above which the upturned eaves project in the usual manner. This combination of classical orders and Chinese brackets is indeed characteristic evidence of how foreign the principles of Greek architecture always remained to the Chinese. Such buildings may have been inspired by Indian models, but the Chinese modified them quite freely by grafting on the pseudo classical models elements inherited from their indigenous wooden architecture.

An entirely different type of masonry work is illustrated by the buildings made after Tibetan models mostly as late as in Ch'ien Lung's reign. The towers and sham fortresses on the slopes of the Western hills in Peking, which were erected in order to give the Chinese soldiers an opportunity to practise assaults, are well known by all tourists. Still larger and more important Tibetan buildings may be seen at Jehol, the famous summer resort of the Manchu emperors in northern Chihli, where an entire Llama cloister was erected after the model of the famous Potala in Lassa, the residence of the Tibetan pope-kings. This enormous brick facade in some nine or ten storeys must in its absolute bareness have appeared quite dreary to the Chinese. They have tried to give it some life or colour by surrounding the windows with pilasters and canopies made of glazed tiles, but the sombre and solid character still dominates, giving evidence of a foreign culture transplanted into Chinese surroundings.

Historical Development.

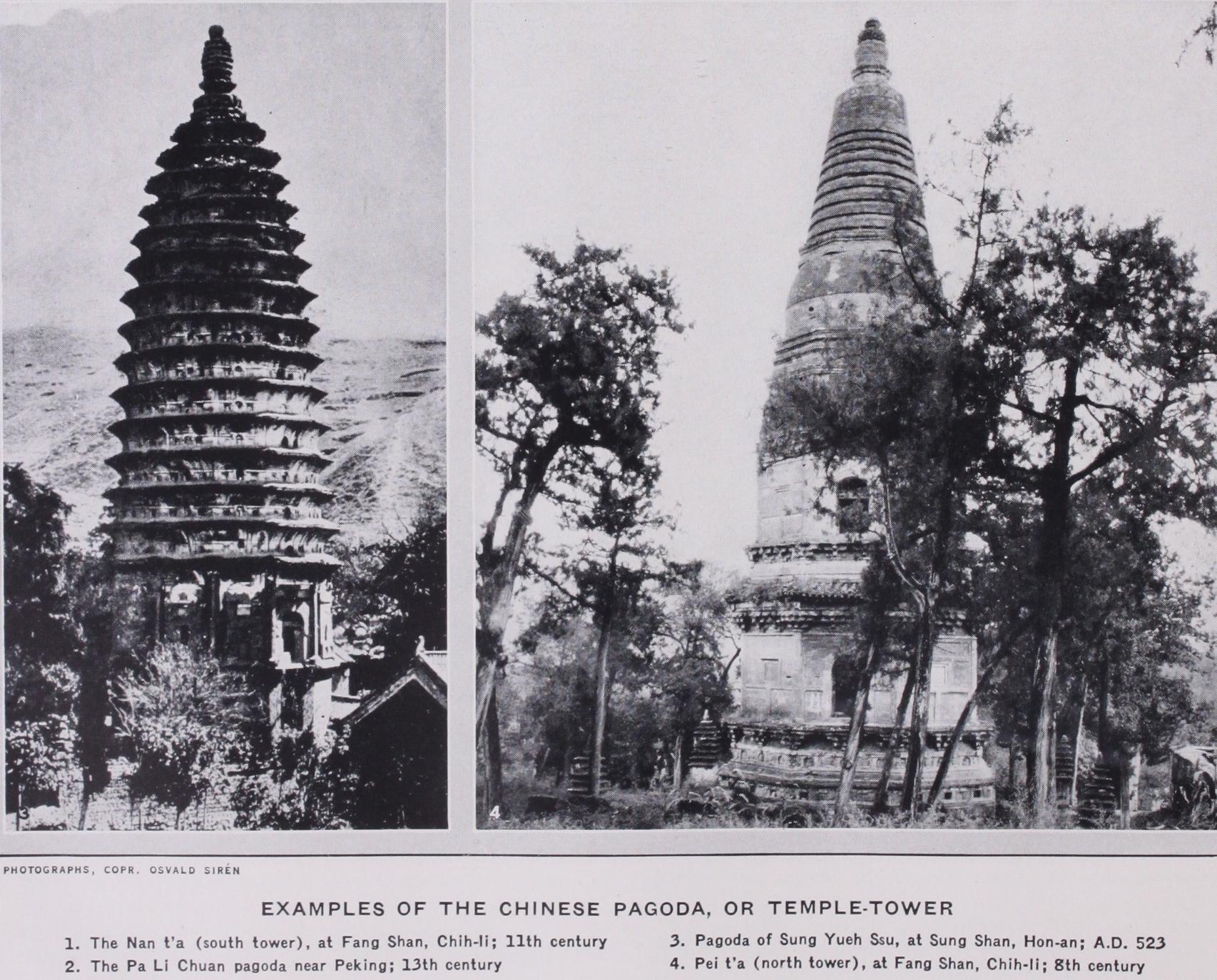

Buddhist temples and pagodas have existed in China since the end of the Han dynasty, and though the earliest ones are no longer preserved, we may obtain some idea about them from old reproductions and contemporary Japanese buildings made after Chinese models. The first mes sages of the new religion were brought to the Chinese at the beginning of our era, but it was not until the end century A.D. that it became more widely spread, largely due to the pilgrims who journeyed between China and India. They brought news not only of the writings and images of the new religion but also of its buildings. It has been reported that small bronze models of the famous stupa of Kanishka at Peshawar (erected in the 1st century A.D.) were brought to China by Hui Sheng, a monk who took part in a mission to India in the year 518. No doubt, other pilgrims did the same, and there may have been many small models of this much admired religious monument in China. As far as one may judge by later Indian reproductions, reverting more or less directly to the famous pagoda of Kanishka, it was built on a square platform, but the main section of it seems to have been round or bottle-shaped and divided by projecting cornices into three or more storeys. Very characteristic of this pagoda was the high mast with its nine superposed metal disks and crowning lotus bud. At present there are no such pagodas preserved in China, but ancient engravings on stone give us reason to believe that they have existed.The oldest pagoda in China still standing is at Sung Yiieh Ssu, a temple on the sacred mountain Sung Shan in Honan. According to historical records, it was built about 523, when the palace pre viously existing here was consecrated as a temple. The tower is made of mud and brick on an octagonal base and reaches a height of nearly 3o metres. The lowest section consists of a plain plinth above which follows a main storey divided by pilasters and win dows in a kind of aedicula (q.v.). The upper section of the tower has the shape of a convex cone; divided by narrow cornices into 15 low, blind storeys. It is crowned by a large bud or cone with nine rings, an equivalent to the mast with the metal disks which is usually found in the wooden pagodas. The early date of the building is verified by the style of the lion reliefs and the mould ings of the main storey.

The character of the whole structure is solid and severe, at the same time the incurvation of the outline prevents any impression of rigidity.

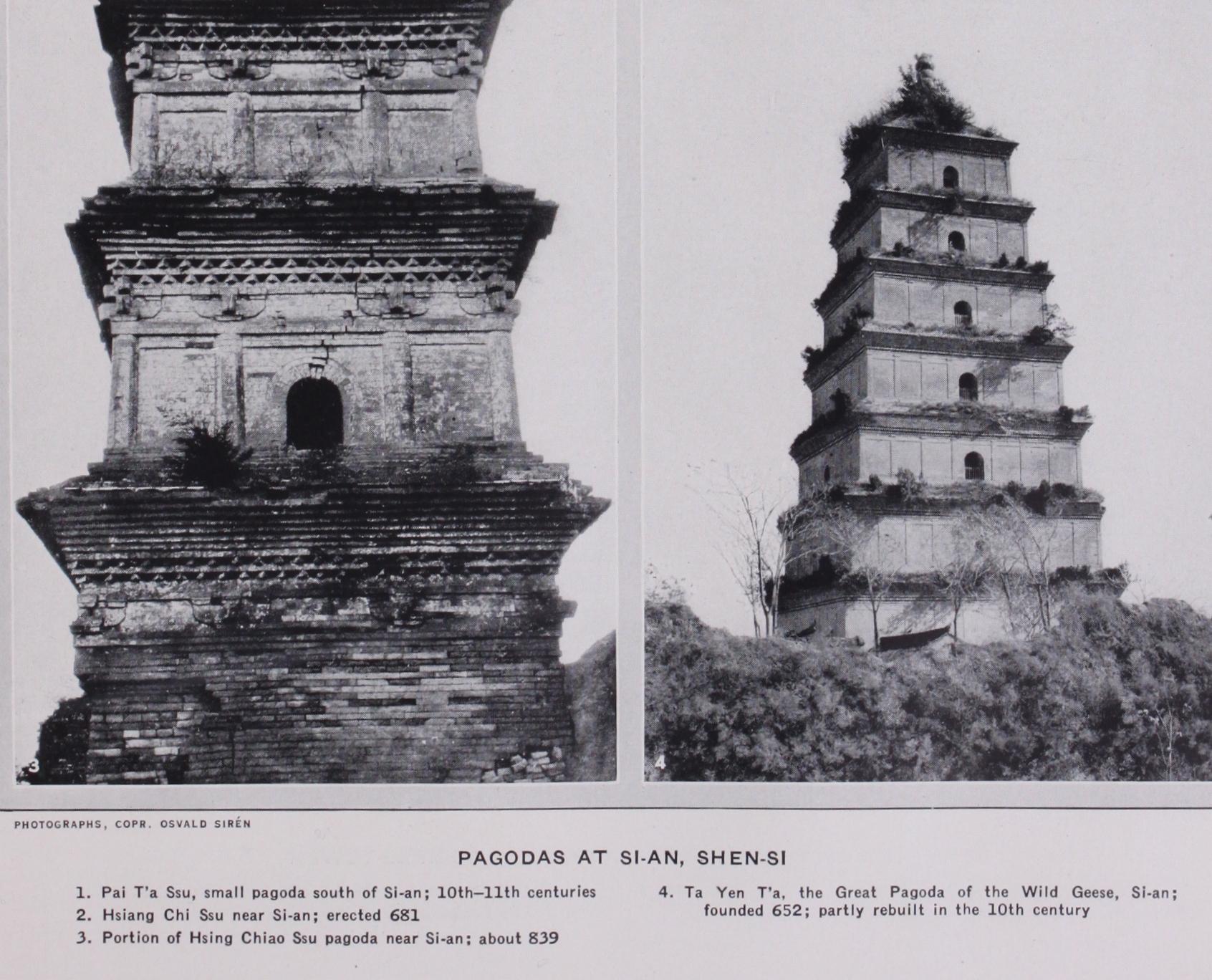

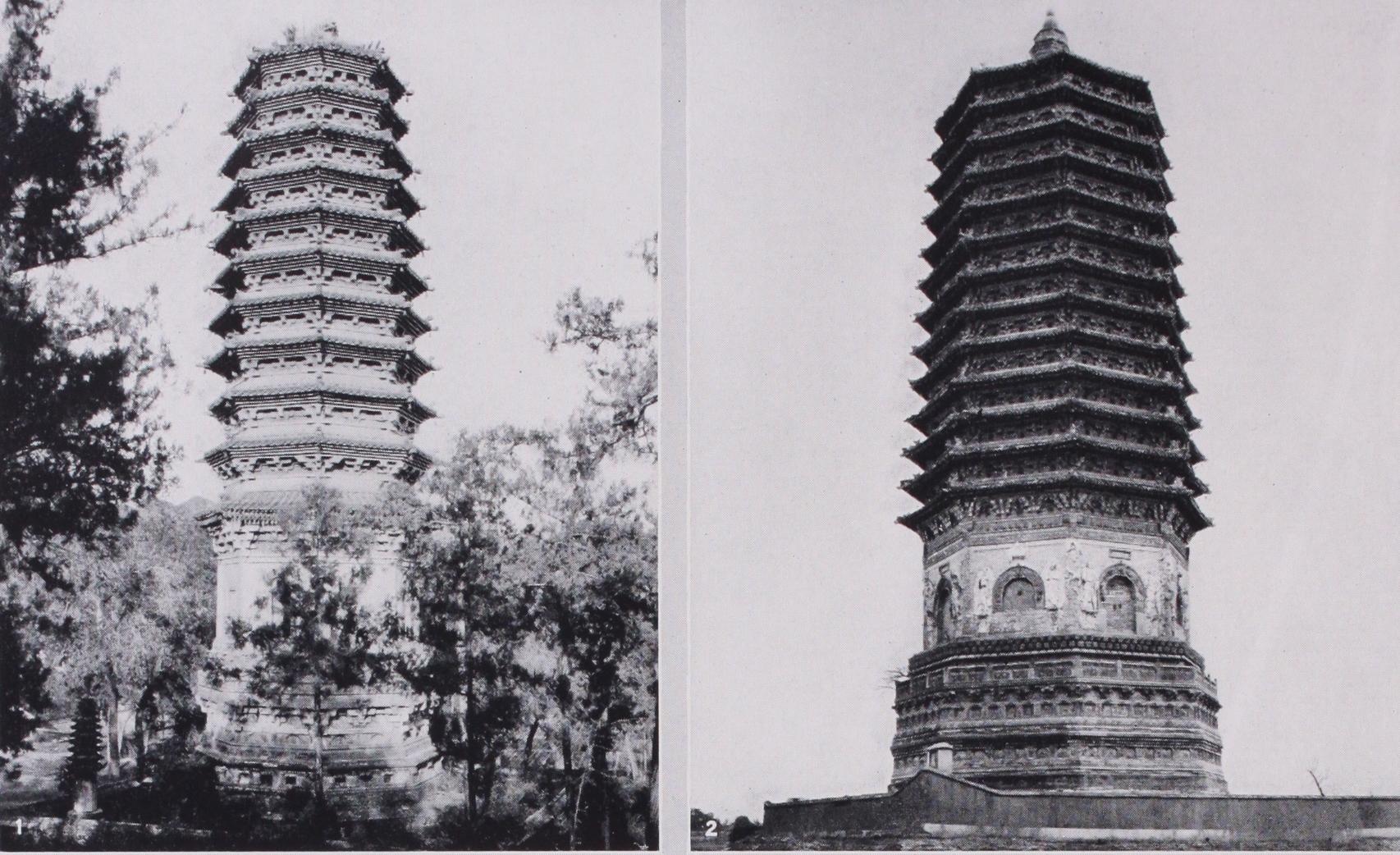

There is no other pagoda of as early date but the type returns with some modifications in some later pagodas, as for instance, the Pei T'a (the North tower) and the Nan T'a (the South tower) at Fang Shan in Chihli. The former, which was built at the beginning of the 8th century, shows a more typically Indian style with its bottle-shaped top, part being on a terraced sub structure while the latter, which was built at the beginning of the I2th century, has a stiffer appearance without any incurvation of the outline or narrowing towards the top. It is divided by brack eted cornices into 11 storeys and reveals by its form and details a closer connection with traditional Chinese constructions. To the same group of buildings belong also the pagodas at Chengtingfu, Mu T'a (T'ien Ning Ssu) built about 1078 in nine storeys with wooden cornices, and the Ching T'a built at a somewhat later period, and furthermore the two big pagodas near Peking, known as Pa Li Chuan and T'ien Ning Ssu, which were erected during the Chin and Yuan dynasties (in the 12th and 13th centuries). They show some likeness to the Nan T'a at Fang Shan, but their dimensions are much larger and their high plinths are richly decorated with figure reliefs in baked clay. Both have 13 low blind storeys and make quite an imposing effect by their great height, but they lack the elastic incurvation which gives to the pagoda at Sung Yiieh Ssu such an harmonious character.

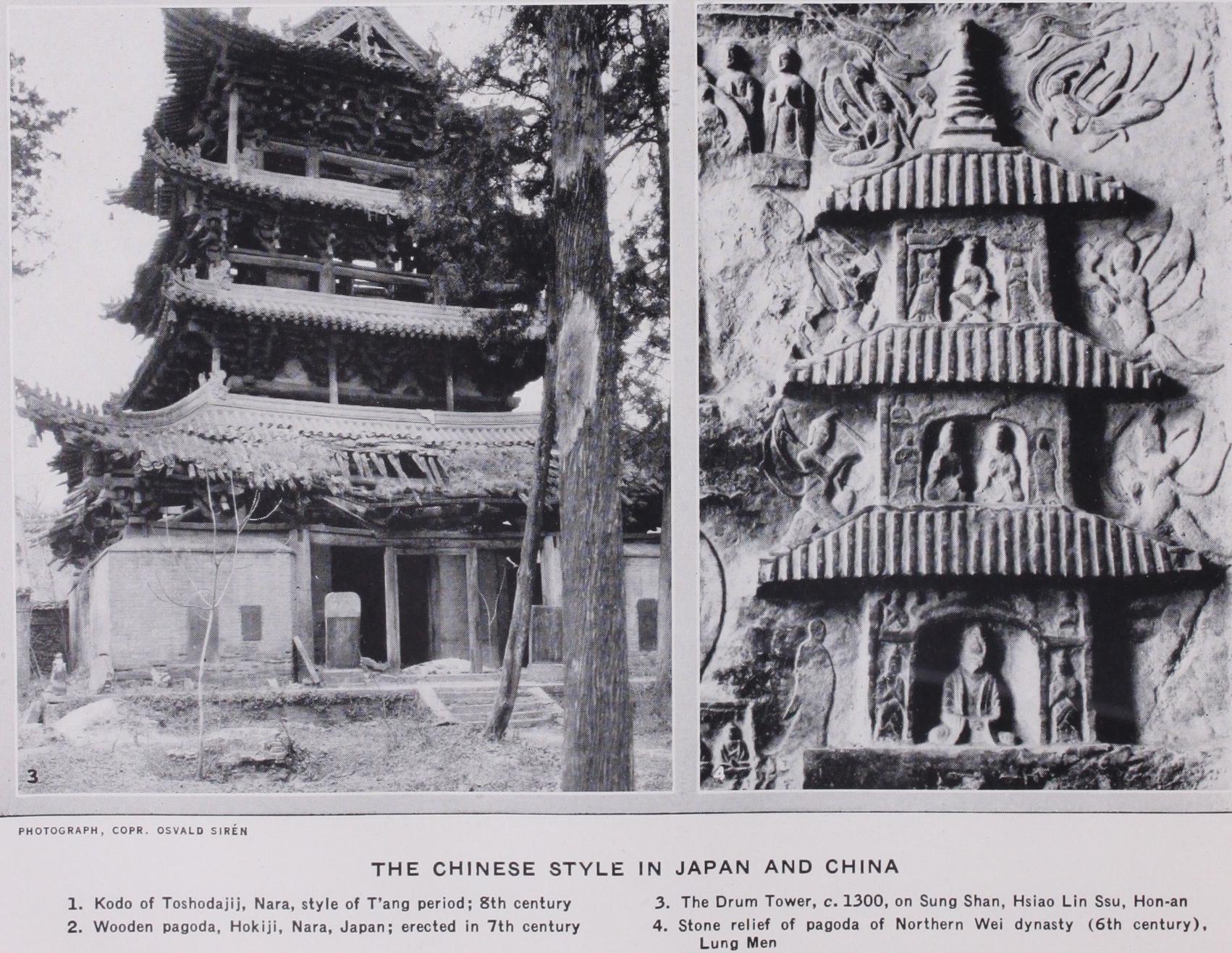

Many of the early pagodas in China were, no doubt, constructed of wood and have perished, cause of the unresisting material. There are records of a very large wooden pagoda erected in A.D. 516 at Lo-yang at the order of the Empress Dowager Hu. ing to Chinese chronicles this was i,000ft. high (a statement which must not be taken literally but merely as a general indication of unusual height) and consisted of nine storeys. Above the tower rose a mast Iooft. high ing 3o gilt metal discs which, as well as the chains by which the mast was tied to the four corners, were hung with no less than Soo gilt bells. This noble edifice became, however, the prey of fire in 534. The description must have been based on hearsay, but it nevertheless has some interest as testimony of the existence of wooden pagodas in China at an early date. It is also confirmed by several reproductions of pagodas found among the cave tures from the beginning of the 6th century at Yun Kang and Lung Men. Here one may see executed in relief pagodas with three as well as with five storeys illustrating exactly the same architectural type as found in the earliest Japanese pagodas from the beginning of the following century. They are built on a square plan with corner posts and projecting roofs over the successive storeys and crowned by high masts carrying discs and ending in the form of large buds or small stiipas. In the successive storeys on some of these pagodas are placed Buddhist statues.

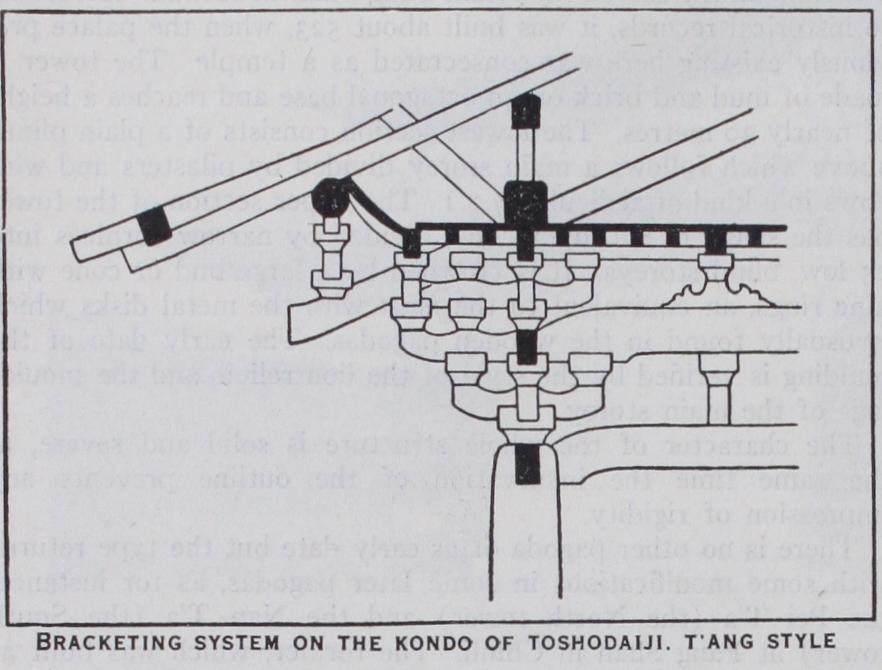

Excellent examples of the same type of pagoda may be seen at some of the old temples near Nara in Japan, as, for instance, Horyuji and Hokkiji which were erected at the beginning of the 7th century in the Suiko period by builders from Korea or China. The pagoda at Hokkiji has five storeys ; the bracketed roofs pro ject quite far but narrow gradually towards the top so that the appearance of heaviness is avoided. Each side has four carrying posts with projecting cantilevers, which at the corners are placed diagonally and cut into the shape of clouds, a motif which is particularly characteristic of this period. The rafters are square and rather substantial; the far projection of the eaves is produced by a very clever construction which no doubt was developed in China before it was introduced in Japan, although the earliest Chinese examples no longer exist. The principle of this system consists in the redoubling of the rafters below the eaves : instead of placing the outermost purlins directly on the cantilevers, which project from the posts, supporting shorter rafters are introduced which are fastened in the beams and trusses of the roof and which carry by means of vertical struts or cushions the further projecting upper rafters. These may be made longer and the roof is lifted higher, the effect becoming lighter than in buildings where the purlins rest directly on cantilevers or beams. This constructive system with redoubled rafters remained in use until the Yuan period, perhaps even later, though the form of the lower rafters as well as other details becomes modified. Furthermore one may notice in these early buildings the very solid and broad shape of the various members, as, for instance, the comparatively short columns with entasis (q.v.) and the very broad and heavy canti levers cut into the shape of clouds at their lower side. The trusses and beams of the roof, to which the rafters are tied, are solid and strong, the various parts being tied together with consummate skill.

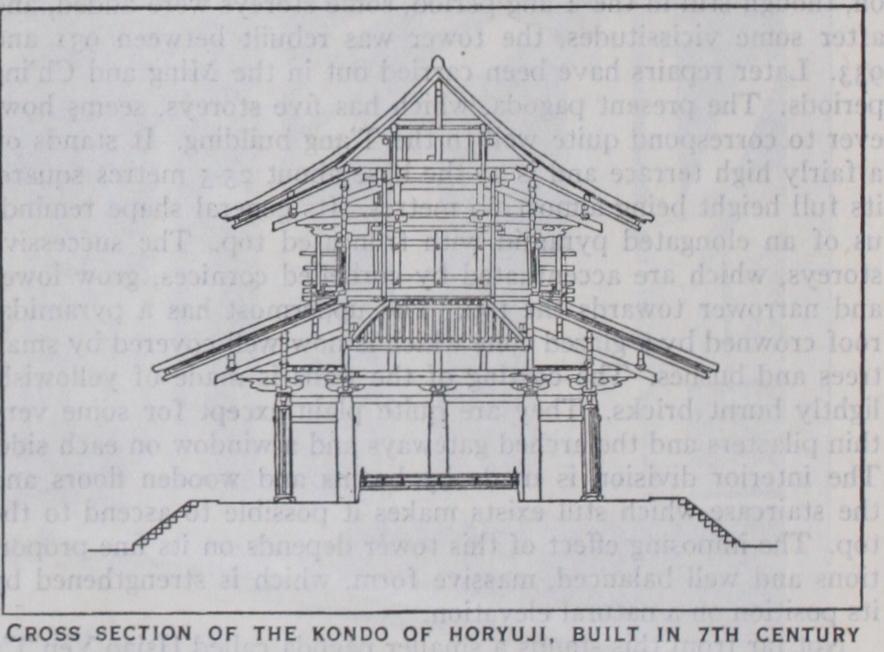

The essential parts of the buildings and the method of con struction are the same in the pagodas and in the temple halls of this period, as may be learned from a closer study of the Golden Hall or Kondo of Horyuji, an oblong, quadrangular room with a colonnade and a roof in two storeys. A very important member added to the pagodas is, however, the mast which runs through the whole height of the tower. The purpose of this mast is not really constructive, it is not meant to support the tower, but simply to form a spire rising high above the roof and carrying the nine metal rings or discs. The builders usually did not tie the mast very tightly to the framework of the tower, because if the whole structure were suspended on the mast, the security of the tower would be jeopardized by the unavoidable swaying of the mast. In some comparatively recent examples one may find the mast suspended in the beams of the tower, but here the intention evidently was to lift it a little above the ground in order to avoid the still greater danger that might arise through the gradual sinking of the tower which would then, so to speak, be carried by the mast or hang on it. In the oldest pagodas which for the longest time have withstood storms and earthquakes the mast is a relatively free-standing post within the structure, always with plenty of room for its swayings, which thus do not really affect the security of the tower.

Quite a number of pagodas and temple halls of the 7th and 8th centuries are to be found in Japan, but it is our purpose here simply to point out certain general principles of construction borrowed from China. The five-storeyed pagoda at Horyuji is, in spite of the verandah which was added later round the ground storey, the most important example, but characteristic of the same style (which was developed in China, during the northern Wei dynasty and in Japan during the Suiko dynasty) are also the three-storeyed pagodas at Hokkiji and Horinji, which remind us of the stone reliefs representing pagodas in the grottoes at Lung Men and Yun Kang.

Inportant modifications of the old style may be observed on the beautiful pagoda of Yakushiji which was erected at the be ginning of the 8th century in close adherence to Chinese con structions from the beginning of the T'ang period. It is a three-storeyed tower, but each one of the storeys is provided with a closed balcony carried on cantilevers, so that the pagoda at first sight gives the impression of a six-storeyed building. The intermediate shed-roofs are of the same shape, though smaller than those which cover the main storeys ; a kind of rhythmic di vision is thus created, and the decorative effect becomes more interesting than in the earlier pagodas. Of great importance for the horizontal articulation are also the far-projecting carrying beams of the balconies, as well as the repetition of the three armed brackets in double tiers under the eaves of the six succes sive roofs. The bracketing system has here attained its highest development, the lower brackets being used as supports for the upper ones which reach farther out and are provided with cushions. Their transversal arms replace the formerly used cantilevers, and on the top of them may be one more tier of similarly shaped brackets, as on other buildings of the same period. It should be observed that all the brackets are complete, the lower ones being so arranged that they carry a continuous beam and also the trans versal arms of the upper brackets, while these serve as supports for the upper beams under the eaves and for the rafters. In order to strengthen the vertical construc tion, struts with cushions are often placed on the hammer beams in the intervals between the brackets.

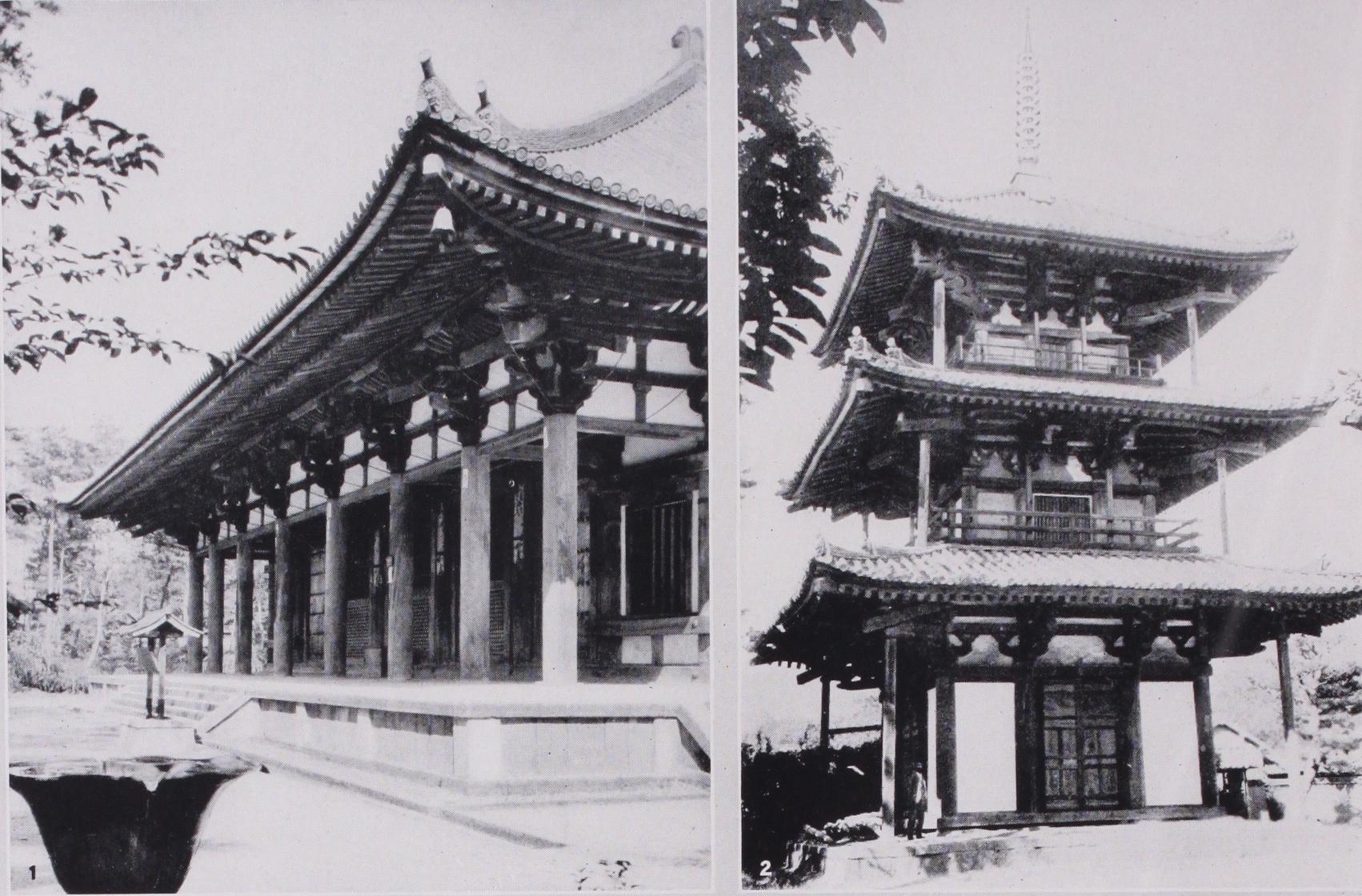

The same characteristic forms and constructive features return in some contemporary temples and pagodas which thus also testify that the parts to which we have paid special attention are typical features of the architec ture of this period. Interesting in this connection are the two large temple halls at Toshodaiji, another temple not far from Nara, i.e., the Kodo (Hall of Teaching) and the Kondo (the en Hall). The former once formed a part of the imperial palace at Nara but was moved to its present place when the temple was erected in 759. The building is quite simple, an oblong, one storeyed hall with double rows of columns all around, the inner row standing free in the room, the outer being filled out to form a wall. The columns are not quite as heavy as on the buildings of the preceding period and the inter-columns are very long. The brackets are introduced only in one tier but between them are struts which contribute to support the roof.

The sail* principles of construction are still further developed on the Kondo of Toshodaiji which, with the exception of its entirely rebuilt roof, is an unusually imposing example of Tang architecture. The building stands on a comparatively broad and high platform, but it is provided with a colonnade only on the front. The columns have a slight entasis and rest on moulded plinths. They are tied together, as usual, by a long architrave-beam and provided with quadrangular cushions from which the three armed brackets project. These carry the upper longitudinal beam and a second tier of brackets. Above this follows a third row of brackets which is almost hidden below the far projecting eaves. The rafters project between the arms of the uppermost brackets and abut against the tranversal arms of the second row of brackets. The rafters are doubled, the upper ones being sup ported by struts which also carry the outermost purlins, and the two layers are furthermore tied by braces. The whole system is carried out with perfect logic in a method which may be termed the highest perfection of wooden construction.

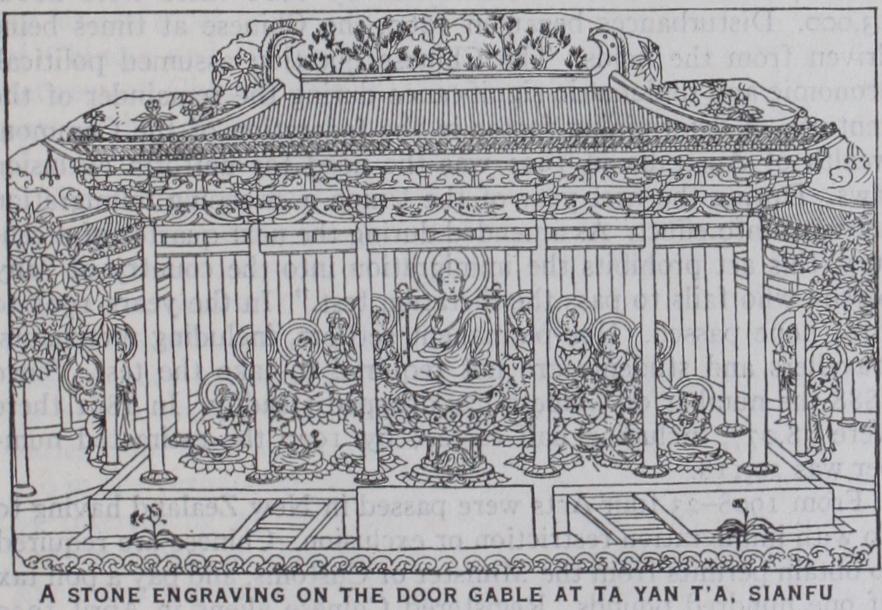

How closely this building depends on Chinese models is proved by the reproduction of a similar temple hall on a large stone gable above one of the gateways to the Ta Yen T'a pagoda at Sianfu. This remarkable engraving which we reproduce from a copy exe cuted by a Japanese artist for Prof. Sekino, is of great historical importance, because it evidently reproduces a Chinese temple on which we may observe the same constructive details as pointed out on the Kondo of Toshodaiji. It matters little that the columns have been made spiky and the roof too small, as long as we recog nize the principle of the whole constructive system, i.e., the brackets and the struts, of which the lower ones have the same kind of curving legs as may be seen on some Japanese buildings of the 9th and loth centuries.

Before following the further development of the traditional wooden construction during the Sung and the Yuan dynasties it is necessary to mention a group of buildings which illustrates an other side of T'ang architecture. These are pagodas in what is popularly called the "Indian style," that is to say, buildings made of packed mud and brickwork which rise in terraces on a square plan. The most important among these pagodas stand in the neighbourhood of Sianfu within or just outside the district which once was occupied by Ch'angan, the capital of the T'ang em perors. In the first place should be mentioned the Ta Yen T'a (the Large Pagoda of the Wild Geese) which was founded in the year 652 by the great Buddhist pilgrim and teacher, Hstian Chuang. It was then made of clay and brick in five storeys ; later on, though still in the T'ang period, some storeys were added, and after some vicissitudes, the tower was rebuilt between 931 and 933. Later repairs have been carried out in the Ming and Ch'ing periods. The present pagoda, which has five storeys, seems how ever to correspond quite well to the T'ang building. It stands on a fairly high terrace and is at the base about 25.5 metres square, its full height being almost 6o metres. Its general shape reminds us of an elongated pyramid with truncated top. The successive storeys, which are accentuated by corbelled cornices, grow lower and narrower towards the top. The uppermost has a pyramidal roof crowned by a glazed cone which is now well covered by small trees and bushes. The coating of the walls is made of yellowish, lightly burnt bricks. They are quite plain except for some very thin pilasters and the arched gateways and a window on each side. The interior division is made by beams and wooden floors and the staircase which still exists makes it possible to ascend to the top. The imposing effect of this tower depends on its fine propor tions and well balanced, massive form, which is strengthened by its position on a natural elevation.

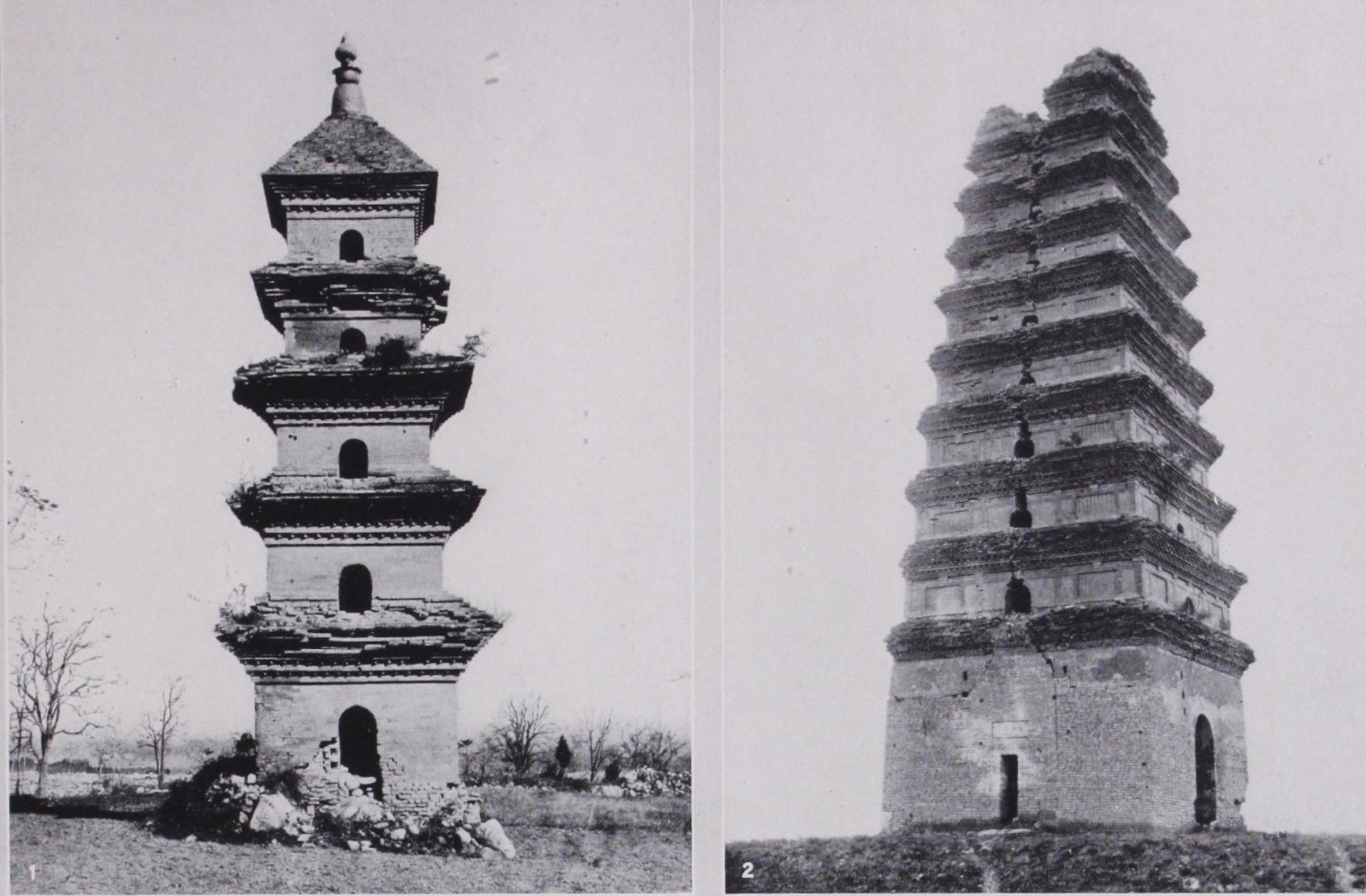

Not far from this stands a smaller pagoda called Hsiao Yen T'a (the Small Tower of the Wild Geese), erected 707-709. This tower had originally 15 storeys but of these hardly 13 are now preserved. The storeys are very low but, as in the previous in stance, accentuated by corbelled cornices. Only the ground floor is a little higher and on the northern and southern side provided with vaulted entrances. The upper storeys have small vaulted windows on the facade but otherwise no openings or divisions, and it is impossible to know whether they ever bad any floors be cause there is no longer any staircase. Externally the tower differs from the Ta Yen T'a by the fact that it is not a stepped pyramid but a square tower with a slight curve on its middle part.

In still worse repair is the Hsiang Chi Ssu, situated a little farther southward from Sianfu. It was erected in 68i according to the same general design as Hsiao Yen T'a, probably in II or more storeys, of which, however, only ten remain. The outline is not curved but rises straight towards the top which is largely ruined. The storeys are quite low but provided with an horizontal and vertical moulding possibly suggested by wooden buildings. The dependence on wooden architecture is still more evident in an other pagoda situated in the same neighbourhood called Hsing Chiao Ssu, which was erected in 839 at the place where the re mains of the great pilgrim, Hsuan Chuang, were removed in 669. It is a comparatively small tower measuring only about 20 metres in height and 5.35 on each side, but it presents an unusual histori cal interest by the fact that some of the most characteristic ele ments of wooden architecture have here been faithfully reproduced in brickwork. The storeys are not only marked by corbelled cor nices but also with rows of three-armed brackets which rise from a kind of horizontal beam and provided furthermore, in the two upper storeys, with carrying posts in the shape of half columns. This close adherence to wood constructions may also be taken as an evidence of the greater age of the wooden pagodas in China as compared with the brick pagodas, which probably were devel oped through influence from India.

On each side of the Hsing Chia Ssu are smaller three-storeyed pagodas erected to the memory of other monks, both having three divisions without any cornices. Such minor quadrangular towers of three to five storeys dating from the T'ang, Sung and Yuan dynasties are often to be found on tombs or other memorable places. One of the largest and most beautiful among them is the Pai T'a Ssu in the same neighbourhood south of Sianfu; others are to be found at Shen Tung Ssu in Shantung and at Fang Shan in Chihli. The same architectural shape may also be observed in the celebrated pagoda Pai Ma Ssu near Honanfu which was not built until the Sung period, though it often has been mentioned as one of the oldest pagodas in China, probably owing to the legend connected with the Pai Ma Ssu temple. It is supposed to have been founded by Indian missionaries, who carried the first sutras to China, but as a matter of fact, the present pagoda was preceded by an earlier one in wood, which perished by fire in 1126. Other characteristic buildings are the Chiu T'a Ssu, or Nine-towered Pagoda, near Lin Cheng in Shantung, and the Lung Kung T'a at Shen Tung Ssu, an impressive square tower in three high divisions, which are encumbered by sculptural decoration.

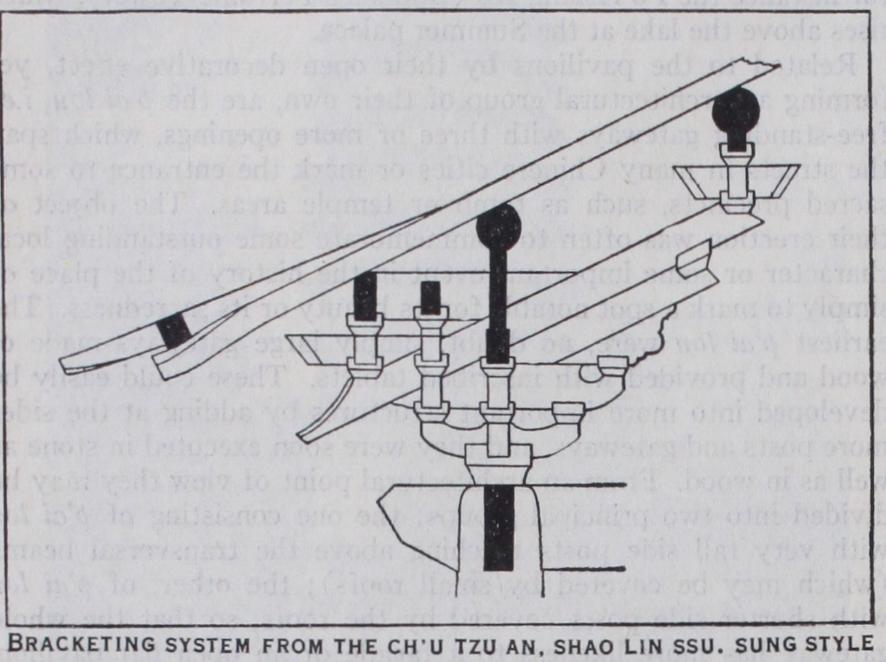

Although the greater part of the buildings which still remain in China from the Tang and Sung dynasties are pagodas made of mud and brick there are also some examples of temples constructed at least in part of wood, dating from the end of the Sung period. The most authentic and important of these is the Ch'u Tzu An hall at Shao Lin Ssu, the famous temple on the slope of Sung Shan in Honan, where the miraculous Bhodidharma, the founder of the Dhyana or Zen Buddhism, is said to have remained several years. According to an inscription, the Ch'u Tzu An was erected about the year 1125 or shortly before. It is a small. square build ing (measuring about 11 metres on each side) standing, as usual, on a stone terrace. Each side has four hexagonal stone pillars but only those of the facade are even partly visible, the others being completely embedded in the brick walls. In the room are two pairs of smaller and two pairs of larger hexagonal pillars, all dec orated with Buddhist reliefs, and the gateway is framed by carved stone beams. Thanks to these solid stone supports the building still stands, but the roof, which is made of wood, threatens to fall in (if it has not already done so). At the writer's visit to the place in 1921 large pieces of the eaves were missing, and perhaps now the building has no other roof than the sky. The most interesting parts of this structure, however, are not the carved stone pillars but the brackets under the eaves which illus trate how these were used in the Sung period. The modifications in comparison with the bracketing system of the T'ang dynasty are quite noteworthy. Thus we find that the brackets emerge not only from the pillars but also, between these, from the hori zontal beam. They are placed more closely together than pre viously, forming a kind of cornice. In the lower tier the brackets have three arms but in the upper tier the transversal arms have been cut by the under rafters, which are pointed and project like beaks or long paws. They are tied by means of braces to the brackets and carry at both ends struts (vertical posts) on which the purlins or corresponding beams rest. This change may be said to imply that the lower rafters have lost their original character and become a sloping cantilever transversing the lower brackets which they lengthen, thus making them better fitted to support the far projecting roof. The modification has evidently a practical purpose, though it hardly improves the original bracket ing system, as exemplified on the T'ang buildings.

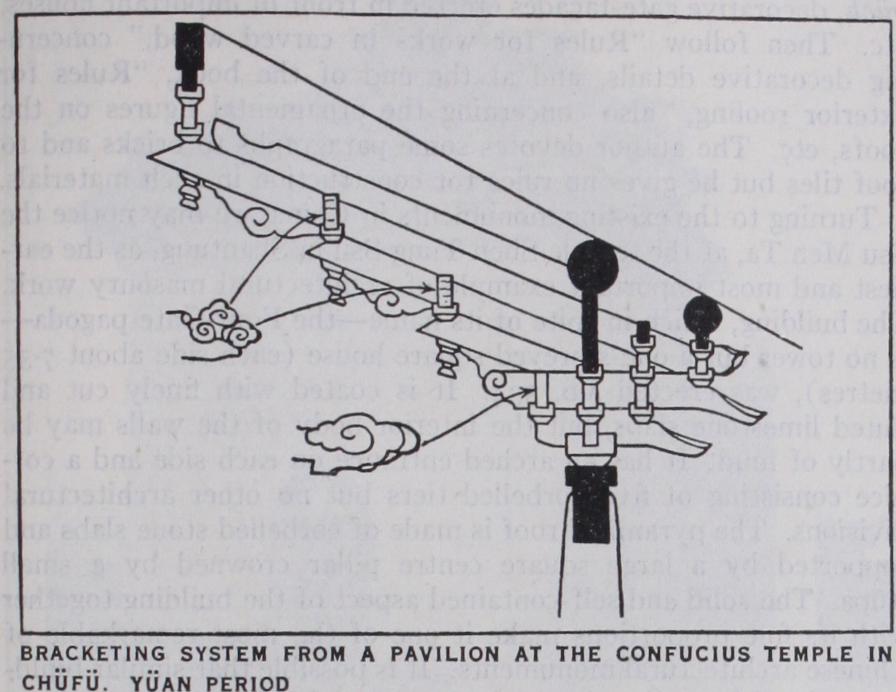

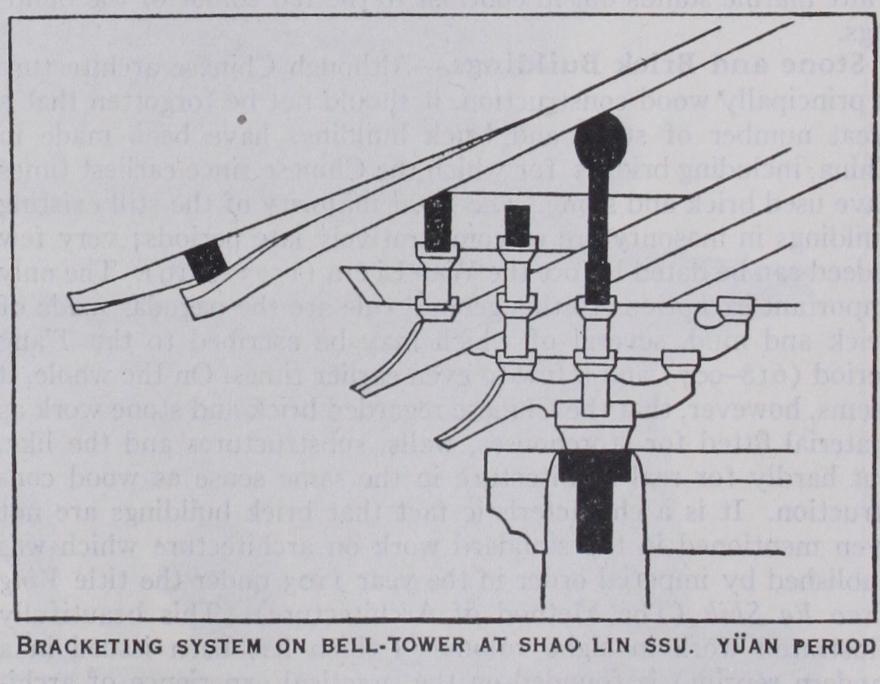

The evolution continued in this same direction; the three-armed constructive brackets gave place to two-armed ones transversed by thin sloping beams or rafters, cut like beaks at the end. These project successively, the one tier reaching beyond the other, each one carrying its row of brackets which serve to support the longi tudinal beams or a kind of struts for the purlins. The former system may be observed on the Bell Tower at Hsiao Lin Ssu, which according to an inscription was erected about the year 1300, where the third storey has no less than four tiers of grad ually projecting brackets with beaks. The latter method is quite common ; as an example may be mentioned one of the pavilions at the Confucius temple at Chi.if u, also of the Yuan dynasty, where the horizontal pieces form a support for several sloping can tilevers (or rudimentary lower rafters) which have been joined into a kind of bed for the struts and purlins of the roof.

Chinese buildings dating from the Sung and Yuan dynasties are scarce indeed, but our knowledge of the architecture of these times may be supplemented by observations on Japanese buildings from the 12th and 13th centuries, i.e., the Kamakura period. In Japan this was a time of great building activity and, accord ing to the best informed Japanese authorities, remarkable for its close imitation of the contemporary Chinese models. Quite im portant in this respect is the Shariden (Chu Tsu An) of the Zen temple Engakuji in Kamakura, built according to the same principles as the above-mentioned Chinese hall, though with an extraordinarily large and high roof covered with straw. This is carried by brackets of the same type as those which were observed at Chu Tsu An of Hsiao Lin Ssu. The brackets are placed so closely together that they form a continuous cornice. The purely Chinese origin of the constructive system of the Shariden of Enga kuji may be confirmed through a comparison with some of the illustrations in the above-mentioned architectural treatise Ying Tsao Fa Shih published in 1103. On the buildings or schematic designs reproduced here we find brackets of exactly the same type as those described above, though their significance is partly obscured by the addition of some large transverse beams which probably have their origin in the imagination of the draughts man.

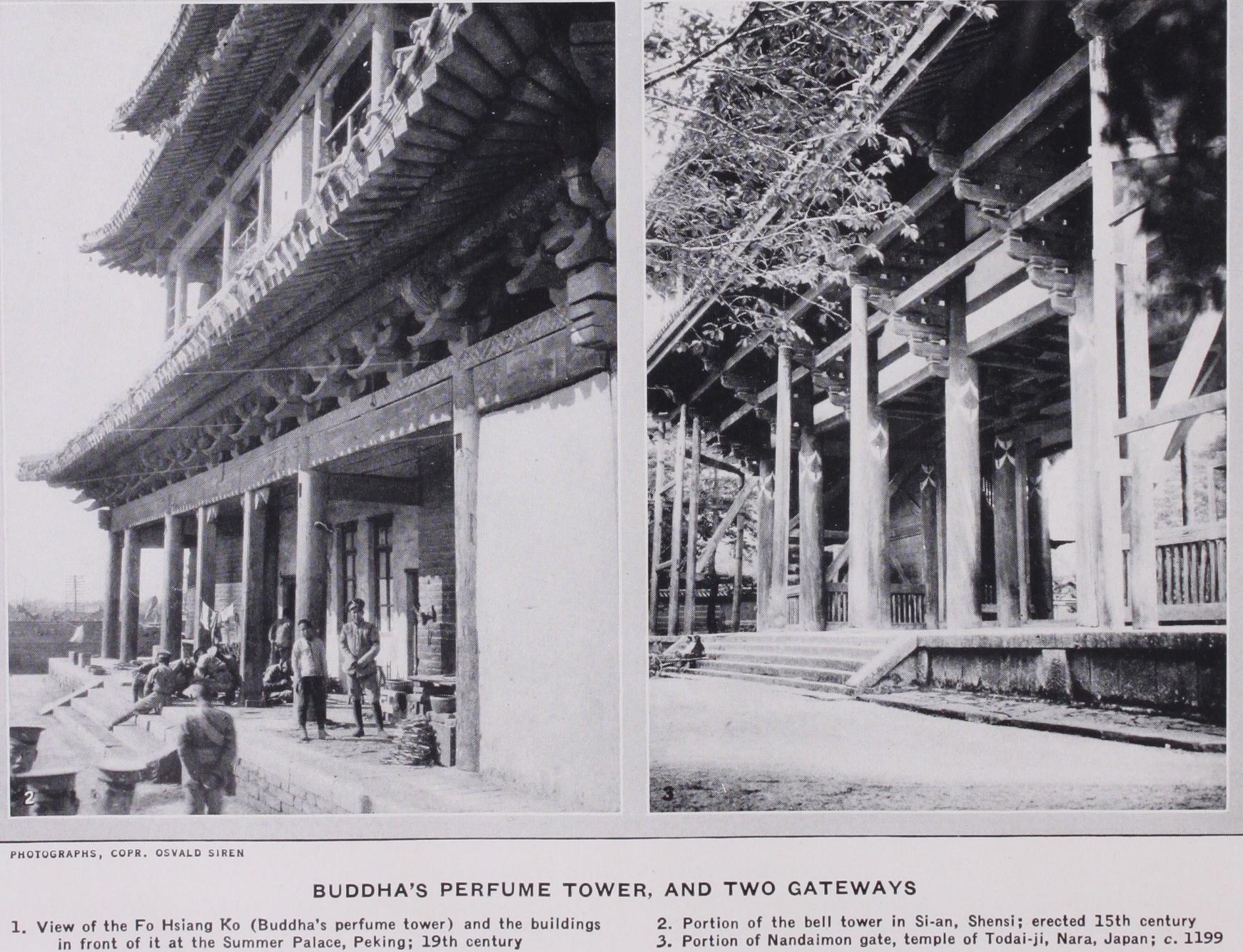

The Japanese called this constructive system which they have borrowed from northern China, "karayo," while another some what different contemporary method was called "tenjiku," be cause it was considered to have been derived from India via southern China. It was used principally at large gates and temple buildings, to which one desired to give a particularly imposing ap pearance by the development of their upper portions. This was achieved by multiplying the brackets and transforming them into straight arms or cantilevers projecting stepwise from the posts. A good example of the tenjiku style is the Nandaimon gate at Todaiji, which was erected in 1199. It has five spans of columns on the long sides and a roof in two storeys, of which the lower one is supported by seven tiers and the upper by six tiers of can tilevers projecting from each column. At the corners are added diagonal cantilevers to form a support for the corner beaks. This kind of construction seems, however, never to have won much popularity in northern China; it is so simple and natural that it hardly can be credited with particular artistic importance. Pro jecting roof beams have indeed been used in many countries to support the eaves, but the characteristic feature of the tenjiku buildings is that the cantilevers are multiplied or massed together by the insertion of intermediate pieces into large composite brackets.

The further development of the wood construction in China after the end of the Yuan dynasty is a question which hardly needs to be discussed, because no real progress can be observed, but rather a gradual decline, which becomes evident in the more and more arbitrary treatment of the bracketing system. At the begin ning of the Ming dynasty one may still find buildings constructed in the same style as those of the Yuan period, i.e., with beak formed pieces laid transversally across the brackets, but the projecting pieces become often clumsy and out of proportion to the brackets. A fine example of early Ming architecture is the Bell Tower in Sianfu, the lower roof of which rests on a double row of brackets of the same type as those of the Yuan buildings. On the other hand, the tower of the eastern gate of T'a Tung Fu, erected in 1371, shows beak-shaped pieces projecting from very feeble brackets.

The question how long a really constructive bracketing system remained in use in China is difficult to answer without more de tailed investigations than have hitherto been made. It is evident however, that already during the latter half of the Ming period simpler methods were applied, as may be seen for instance on the earliest buildings in the Forbidden City in Peking. It is true that the outer appearance was kept up by fixing multiple rows of brackets and pointed beaks below the eaves, but these have no real constructive function. The purlins rest on projecting beams or on struts standing on the col umns. The closely arranged and freely multiplied brackets and beaks which we find on the big palace halls and imposing gate towers in Peking are nothing but ornamental cornices, the decorative effect of which nobody will deny. The roof would indeed rest just as well on the build ing even if these sham brackets were taken away. The forms are still the same as be fore but they have lost much of their sig nificance because they lack inner necessity.

The particular quality and importance of the old architecture of China depended on its firm and clearly developed wood con struction. It was purely carpenters' art, and based on the special requirements of the material. Each part had a definite function which was not concealed by any superimposed decoration. This architec ture was logical and purposeful and it remained a living art as long as the original principles of construction were kept up, but once these were encroached upon by purely decorative tendencies, both vitality and further growth were at an end. (See also JAPANESE ARCHITECTURE.) (0. S.) only original Chinese work on architecture is the Ying Tsao Fa Shi (1 io3 ; 2nd ed., 1145; reissued by the Shanghai Commercial Press) . Good accounts of the work were given by P. Demieville in Bulletin de l'Jcole Francaise d'Extreme-Orient, tome xxv. (1925), and Percival W. Yetts in the Burlington Magazine (March, 1927), the latter containing a discussion of earlier European books dealing with Chinese architecture. Of greater importance are, however, the works published by various Japanese authorities on their own early buildings since these are closely connected with those of China. See Japanese Temples and their Treasures (last ed. 1915) ; also articles in the Kokka and other Japanese reviews, especially C. Ito and J. Tsuchija's report about the imperial palaces in Peking, in the Bulletin of the School of Engineering of the Tokyo Imper. University (19o5), a kind of text for the portfolio publications; Photographs of Palace Buildings of Peking and Decoration of the Palace Buildings of Peking (1906). See also Boerschmann, Baukunst and religiose Kultur der Chinesen (1911-14) and Chinesche Archi tektur (1925) ; Osvald Siren, The Walls and Gates of Peking (1924), and The Imperial Palaces of Peking (Paris, 1926) ; Tokiwa and Sekino, Buddhist Monuments in China (Tokyo, 1926-27), of which only one part has been issued in English.

The drawings of this article are executed partly on the basis of sketches by Prof. Sekino and partly after photographs by the author.