Chinese Music

CHINESE MUSIC. Music played a great part in the origins of ancient Chinese civilization, the pitch-pipe of the normal pitch (called Huang-chung) was the basis of the Chinese sys tem of measures, of the calendar and of their astronomical calcu lations.

A Musical System.

According to tradition, the emperor Huang-ti (c. 2697 B.c.) sent his minister Ling-lun to the Kun lun mountains in north-west China to cut a pitch pipe from a species of bamboo which gave the note Huang-chung. Eleven other notes were derived from this note by the following process: a third part of the nine-inch pipe Huang-chung was cut off, thus producing a second pipe, Lin-chung, which was six inches long (9 X) and gave the fifth. The second pipe was divided into three parts, and one of the third parts was added to it (8 in. or 6 X 4) ; this gave the descending fourth (Tai-tsu) from the second pipe, and so on. This was the origin of the 12 Chinese pitch pipes; Huang-chung Tai-tsu (D), Chia-chung (D#), Ku-hsi (E), Chung-lu (F), Jui-pin (F#), Lin-chung I-tse (G#), Nan-lu (A), Wu-i (A#), and Ying-chung (B). The Chinese system of fifths is first mentioned in the work Lu-Tsu Chun-Chiu, which dates from the 3rd century B.C.-about the time when the Pythagorean musical system was made known in Greece by the pupils of Pythagoras.As the circle of fifths could not be closed owing to the (Py thagorean) comma, the Chinese made a number of attempts in the course of the ages to divide the octave into 6o notes (King fang, c. 4o B.c.), 36o notes (Chien-lo-chih, c. A.D. 430), 18 notes (Tsai-yuan-ting, c. A.D. I 18o), and 12 notes (Ho-cheng-tien, c. A.D. 42o and Wang-po, c. A.D. 958), equal and unequal temperament respectively. The old system of fifths still continued however to be the prevailing system. Finally, Prince Chu-tsai-yu, in a century earlier than Andreas Werkmeister (1691) in Europe, fixed the twelve pitch-pipes in equal temperament; in order to obtain the nearest semitone he divided the length of a pitch-pipe by 1.0594631 2 and its diameter by 1.0292857 or 2 j 2. The mathematical and physical basis was confirmed by experiment by the Belgian authority on acoustics, V. Ch. Mahillon.

The ancient Chinese scale has five tones: Kung (C), Shang (D), Chiao (E), Chih (G) and Yu (A). Later, under the Chou dynasty (1I22-255 B.c.), two further notes, Pien-chih (F#) and Pien kung (B) were added.

Each note of this scale of five or seven notes can be used as the primary note of a scale, and this gives five or seven modes, just as in Greek music we have the Doric, the Phrygian mode, etc. As each of these five or seven modes can be transposed in twelve ways, there are 6o or 84 keys in Chinese music. (X.) Musical Practice.—The ancient theory and the classical music of past centuries are connected almost exclusively with the rites and ceremonies of the temples of worship and of the court. One of the old literary classics, the Li Ki or Book of Rites, contains many allusions to music ; and one whole section (said to be a later interpolation) is devoted wholly to music in its ethical, ritual and symbolic aspects. Until a few decades ago the Imperial Ministry of Rites included a bureau of music, but the function of this office seems to have been entirely a matter of ceremonial tradition, and to have had no connection with the practice of music in its popular forms. The performance of ritual music was continued in certain places up to most recent times with a scrupulous adherence to tradition. The solemn celebration of the highest office of the Confucian worship is accompanied by a tra ditional orchestra of 44 pieces. Taoist temples are content with about six instruments. In the Confucian solemn rite the Emperor himself was supposed to be the chief celebrant. The pentatonic, non-harmonic music for this celebration has often been reproduced in European notation in the books on Chinese music, particularly the solemn march to which the imperial worshipper proceeded to the door of the temple and the concluding monodic hymn to Con fucius (Ta tsai K'ung tsen) in which all the instruments and voices took part.

Music outside the temples is more popular in character and has probably been subjected to more frequent changes in style; although even here the tenacious conservative instincts of the race have handed down a more archaic type of music to the present day than is known in the occidental countries. The practice of this music by individuals, particularly by amateurs of high social status for their own aesthetic satisfaction is not so wide spread in China as in the West. Home or household music seems to have been more highly developed in Japan than in China. There is, in China, no well organized class of professional music teach ers. Most musicians acquire their art in a purely empirical way, although there is a considerable body of books containing the notations of tunes for various instruments. This notation is not a staff notation, but a tablature system, that is, a series of signs or symbols for the individual tones, frets or finger positions. Vocal music has an important place in the temples and still more in the theatre. Apart from this it is not cultivated as an art co-ordinate with instrumental music to the same extent as in Western nations, although the singing of songs and ballads is not uncommon.

Musical Instruments.

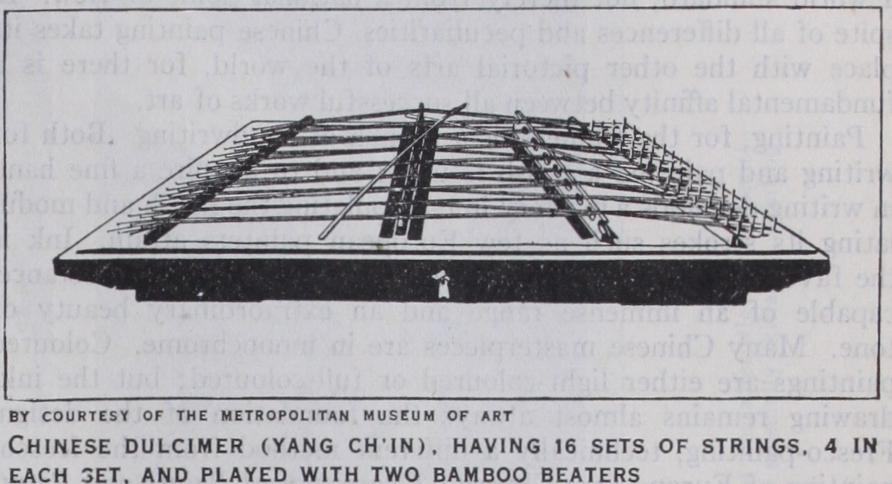

The number of instruments used by the Chinese is comparatively large. Moule lists and describes not fewer than 13o. Many of them are, to be sure, mere toys or signal instruments of no great musical importance. They are used by mountebanks at fairs or markets, and by hawkers or beg gars. European writers about Chinese instruments devote much space to the description of the ancient classic instruments used in temple worship, many of which have long since gone out of com mon use. They are largely per cussion instruments, including many forms of highly ornamented drums (Ping ku, g ; po fu, 411j' ; pang ku, ow, sonorous stones single (t'e k'ing t14) or arranged in chimes (pien k'in ign ) or bronze bells used in the same manner (po pien chung Nit) . The k'in g is a narrow hollow box 3 to 4 ft.in length, with slightly convex upper surface. It has five, or in more modern instruments, seven silk strings plucked with the fin gers, and was still used until fairly recent times for refined artistic music. Its Japanese coun terpart is the koto. A larger in strument constructed on the same principle, but having in earlier times as many as 5o strings, later only about 25, is the se, rarely used except in ceremonies. The an cient instruments were classified by the older theory according as they produced the sound of stone, metal, silk, bamboo, wood, skin, gourd and earth. The most important instruments still in use are the two-stringed fiddle, hu k'in, )j ; the four-stringed moon guitar, y"ueh k'in, JEJ ; the f our-stringed, pear-shaped, balloon guitar, p'i p'a, g ; the three-stringed guitar with a very long neck, san hsien, Eg, a first cousin of the Japanese samisen. Of the flute type are the straight (direct) flute hsiao ; and the transverse flute ti, M. Reed instruments are represented by the gentle kuan straight bamboo tube, 8 to Io in. long, with a rice straw serving as a double reed or oboe mouthpiece ; and the shrill, so na VON, a double reed instrument with a conical wooden body ending in a metal "bell," often called the Chinese clarinet. The sheng consists of a lacquered wooden body (formerly a gourd or czlabash), about the shape and size of a tea cup, and a mouth piece through which the player inhales the air. On the body are grouped 13 to 17 speaking pipes, slender bamboo tubes each pro vided with a thin, free reed of metal. Each tube has a hole below the reed and the pipe speaks only when the hole is stopped by the player's finger. The yang k'in, f , or foreign psaltery, consists of a trapezoidal sound box about 2 ft. in width over which are usually stretched 14 to 20 double, triple or quadruple sets of metal strings which are played by striking them with two light bamboo rods.

Modern percussion instruments, used chiefly in the theatre, include the large gong (lo ), cymbals (po ), a flat circular drum, struck with a pair of light sticks (pang ku isn) and sharply resonant wooden blocks or castanets (pe pan 4M) . Before the revolution of 1911-12, professional musicians had no high social standing. Those who played in the theatre commanded more respect than the players in funeral or wedding processions. Courtesans and beggars who played and sang, and ballad singers were of the lowest rank. The Chinese theatre makes copious use of music, the drama being practically a music drama. A relatively very small part of the play is given over to unaccompanied spoken dialogue. The recitative portions are either punctuated by the percussion instruments or are invested with a continuous rhythmic accompaniment of these instruments which often drown out the actor-singer's voice. The lyric portions of the performance are accompanied by the fiddles, guitars, flutes or pipes. The protag onist selects the tunes from among a large number of well-known conventional strains or motives, said to be very old. The instru mentalists accompany in unison, although, since they play without written music, embellishments and variations are produced ad libitum, and there are at times instances of the use of double notes and traces of an embryo type of contrapuntal invention. The Chinese ideal of good vocal performance, particularly for the male actors, requires a high, forced falsetto tone production.

All of this music, as well as the popular music of funeral and wedding processions and of street songs is, like the sacred music, distinctly pentatonic. But where, as in the popular orchestra or solo performance, the art of improvisation and embellishment has free play, the larger intervals of the five-tone scale are fre quently filled out in runs and figures, as a careful analysis of phonograph records (Erich Fischer) has shown. But even here the importance of the pentatonic skeleton or foundation is beyond doubt and is easily sensed by the European hearer. Since the revolution the influence of Western music has become more marked.